7.1

A thorough and systematic assessment of a patient should lead to a comprehensive diagnostic statement. The first component of this is the multi-axial diagnostic formulation.

7.2

A multi-axial diagnostic formulation provides a contextual and standardised description of the clinical condition through a number of highly informative, therapeutically significant and systematically assessed axes or domains.

7.3

A tetra-axial formulation is recommended as follows:

-

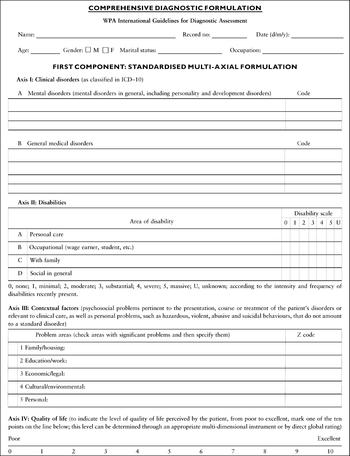

(a) Axis I: clinical disorders (mental and general medical conditions);

-

(b) Axis II: disabilities (in personal care, occupational functioning, functioning with family, and broader social functioning);

-

(c) Axis III: contextual factors (interpersonal and other psychosocial and environmental problems);

-

(d) Axis IV: quality of life (primarily reflecting patient's self-perceptions).

7.4

Axis I (clinical disorders) consists of all relevant psychiatric disorders (including personality and developmental disorders) and general medical conditions that are identified on the basis of a comprehensive historical anamnesis, evaluation of symptoms, mental state examination, supplementary assessment instruments and the physical examination. Disorders are to be listed in their order of importance for disposition and care.

7.5

Axis II (disabilities) comprises ratings of impairment in important areas of adaptive functioning. Impairments may be the result of mental disorders, physical disorders, or both. Included are impairments in four separate areas of functioning, as follows:

-

(a) personal care and survival;

-

(b) occupational functioning, including roles as paid or volunteer worker, student or homemaker;

-

(c) family functioning, including interaction with spouse, children, parents and other relatives;

-

(d) broad social functioning, including roles, activities and interactions with other individuals and groups in the community at large.

Ratings are to be made for each area of functioning, using a semi-quantitative six-point scale based on frequency and intensity of impairments (Fig. 7.1). The scale anchor point descriptions are: 0, none (no identifiable disability); 1, minimal (disability low in both intensity and frequency); 2, moderate (disability medium in either intensity or frequency, low in the other); 3, substantial (disability medium in intensity and frequency); 4, severe (disability high in intensity or frequency, lower in the other); 5, massive (disability high in intensity and frequency).

Fig. 7.1 Blank form for making a comprehensive diagnostic formulation. First component: standardised multi-axial formulation. This form may be photocopied free of charge for use in clinical practice.

7.6

Axis III (contextual factors) consists of all relevant psychosocial and environmental problems. Such problems may be relevant to the onset, exacerbation or maintenance of a disorder listed on Axis I, or be in themselves targets of clinical care. They may be acute events or chronic circumstances. This axis also includes personal problems that do not amount to a disorder proper, but are of clinical significance (e.g. accentuated personality, or hazardous, violent, abusive or suicidal behaviours). Contextual factors can be coded according to the ICD—10 Z-codes (factors influencing health status and contact with health services).

7.7

Axis IV (quality of life) is a multi-dimensional and global assessment of the patient's self-perceived well-being in areas such as physical and emotional state; satisfaction with independent, occupational and interpersonal functioning, and with socio-emotional and instrumental supports; and a sense of personal and spiritual fulfilment. Its assessment should be culturally informed. Its appraisal may be based on one of the many standardised quality-of-life instruments available or on a direct global self-rating using a scale such as that provided on the proposed diagnostic formulation (Fig. 7.1).

7.8

Domains of the multi-axial formulation should be assessed with sensitivity to the culture of the patient. The identification and rating of the importance of significant problems in health, functioning and social context should be made in relation to pertinent cultural norms and customs.

7.9

The completion of a multi-axial assessment is made easier by the availability of a reprinted record sheet in the patient's clinical chart, in a format designed to ensure that all the domains of the multi-axial schema are attended to and systematically appraised. An example of such a completed form is given in IGDA Workgroup, WPA (2003b , this suppl.: Appendix 2).

7.10

The main purpose of the multi-axial diagnostic formulation is to inform the preparation of a comprehensive treatment plan (see IGDA Workgroup, WPA, 2003a , this suppl.). Additionally, it may facilitate and optimise longitudinal reassessments of the patient's condition and therefore afford a refinement of the validity of clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, it can serve as an outcome measure of therapeutic interventions.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.