Introduction

With a population of nearly 1 billion, domestic dogs Canis familiaris are the most ubiquitous carnivore, occurring almost everywhere humans live and even in some places where people are practically absent (Daniels & Bekoff, Reference Daniels and Bekoff1989; Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014a,Reference Gompper and Gompperb). Although the movement of dogs may be restricted by their owners, many dogs spend some or all of their lives in an unrestrained state. These free-ranging dogs include stray and feral dogs, as well as a large portion of owned dogs. There is often little or no control over their movements or behaviours regardless of their status as either owned or unowned animals (Vanak & Gompper, Reference Vanak and Gompper2009a). Free-ranging dogs may be a global concern for wildlife conservation, and especially for threatened large mammals, and are therefore receiving increasing attention from researchers and conservationists (Hughes & Macdonald, Reference Hughes and Macdonald2013; Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014a,Reference Gompper and Gompperb; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dickman, Glen, Newsome, Nimmo and Ritchie2017; Home et al., Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a).

Although free-ranging dogs are largely dependent on people for food and shelter, and although a significant portion of these dogs live in urban contexts, there are nonetheless large populations of dogs inhabiting rural areas and remote natural landscapes. In these settings, dogs have been observed to negatively affect many wildlife species, including in protected areas (Vanak et al., Reference Vanak, Dickman, Silva-Rodríguez, Butler, Ritchie and Gompper2014; Sepúlveda et al., Reference Sepúlveda, Pelican, Cross, Eguren and Singer2015; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dickman, Glen, Newsome, Nimmo and Ritchie2017; Home et al., Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a). Free-ranging dogs have been reported to endanger 188 threatened taxa and to have contributed directly to the extinction of 11 species (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dickman, Glen, Newsome, Nimmo and Ritchie2017). With an increasing global dog population and an associated expanding impact of free-ranging dogs, there is an urgent need to recognize the importance of the issue and to provide strategies for informed management of dog populations that reduces their negative effects on wild mammals (Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014b; Home et al., Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a).

Free-ranging dogs can affect wildlife in multiple ways, including through direct predation and competition, by causing fear-induced behaviours, through the transmission of pathogens and by hybridization with native canid species (Molina & Peñaloza, Reference Molina and Penaloza2002; Butler & du Toit, Reference Butler and du Toit2002; Butler et al., Reference Butler, du Toit and Bingham2004; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Esteves, Ferraz, Crawshaw and Verdade2007; Young et al., Reference Young, Olson, Reading, Amgalanbaatar and Berger2011; Silva-Rodríguez & Sieving, Reference Silva-Rodríguez and Sieving2011; Knobel et al., Reference Knobel, Butler, Lembo, Critchlow, Gompper and Gompper2014; Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014a; Leonard et al., Reference Leonard, Echegaray, Randi, Vila and Gompper2014; Zapata-Ríos & Branch, Reference Zapata-Ríos and Branch2016, Reference Zapata-Ríos and Branch2018). Furthermore, free-ranging dogs can depredate livestock and thereby intensify and complicate conservation conflict. In India, for example, most of the livestock depredated in a Trans-Himalayan agro-pastoralist landscape were attacked by free-ranging dogs, potentially disrupting conservation programmes designed to protect species such as the snow leopard Panthera uncia (Home et al., Reference Home, Pal, Sharma, Suryawanshi, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017b).

Although lack of adequate feeding of free-ranging dogs may amplify negative impacts on wildlife (Silva-Rodríguez & Sieving, Reference Silva-Rodríguez and Sieving2011; Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014b; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Dickman, Letnic, Vanak and Gompper2014), even those dogs that are fed sufficiently can be problematic for wildlife if they occur in large numbers or travel within protected areas (Vanak & Gompper, Reference Vanak and Gompper2009a). For example, livestock guarding dogs are used to protect livestock from large predators and thereby reduce conflicts in areas where people and wildlife co-occur (Khorozyan et al., Reference Khorozyan, Soofi, Soufi, Hamidi, Ghoddousi and Waltert2017; Behmanesh et al., Reference Behmanesh, Malekian, Hemami and Fakheran2019; Mohammadi et al., Reference Mohammadi, Kaboli, Sazatornil and López-Bao2019). However, in some countries such as in Iran, these dogs mostly receive protein-poor foods such as bread dough, which may require them to consume wild prey to meet nutritional and energetic demands. Such scenarios may be typical of regions where, because of economic limitations or social norms, owned dogs are not fed commercially-produced dog foods (Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014b; dos Santos et al., Reference dos Santos, Le Pendu, Giné, Dickman, Newsome and Cassano2018).

Despite an increasing understanding of the potential for free-ranging dogs to interact negatively with wildlife, in many parts of the world there remains a dearth of information on the topic. For example, Iran is the second largest country in the Middle East, and yet the possible impacts of free-ranging dogs on the country's mammals have never been investigated. Iran has a rich mammalian fauna comprising 192 species in 34 families (Yusefi et al., Reference Yusefi, Faizolahi, Darvish, Safi and Brito2019). The main economic activities in the rural villages of Iran, especially those near or adjacent to protected areas, are agricultural practices, with livestock husbandry being an essential source of income for local people. Livestock farmers typically graze small herds of domestic sheep Ovis aries and goats Capra hircus on rangelands around small villages, with shepherds accompanied by livestock guarding dogs (Darvishsefat, Reference Darvishsefat2006; Khorozyan et al., Reference Khorozyan, Soofi, Soufi, Hamidi, Ghoddousi and Waltert2017; Mohammadi et al., Reference Mohammadi, Kaboli, Sazatornil and López-Bao2019). The nomadic lifestyle and pastoralism of Indigenous people who inhabit rural regions of the country also involves keeping dogs to protect against theft and depredation.

Such lifestyles probably facilitate the potential for free-ranging dogs to have negative impacts on wildlife, including taxa of conservation concern such as the Critically Endangered Asiatic cheetah Acinonyx jubatus venaticus (Farhadinia et al., Reference Farhadinia, Hunter, Jourabchian, Hosseini-Zavarei, Akbari and Ziaie2017). However, there is little information about direct predation by free-ranging dogs on Iranian or Middle Eastern wildlife more widely (Manor & Saltz, Reference Manor and Saltz2004). Effective management programmes for reducing attacks by free-ranging dogs on wildlife first require a comprehensive assessment of the extent of dog–wildlife interactions. Here we conduct a review to examine the extent of interactions between free-ranging dogs and Iranian wild mammal species. We focused on documenting the spatial extent and mammal species attacked, and their national and global IUCN Red List status (Yusefi et al., Reference Yusefi, Faizolahi, Darvish, Safi and Brito2019). We also examined how such attacks occur, by assessing the context of the interactions, the number of dogs involved and the outcome of the attacks (injury or death).

Given the dearth of published research on the topic, we used traditional and social media reports to help us document the scope and scale of attacks. Social media can shape perceptions of human–wildlife interactions and the ability to coexist with wildlife, and in many regions they are the primary source of information on wildlife-related news. Most newspapers now have both a website and a social media page (Ju et al., Reference Ju, Jeong and Chyi2014). Such media reports serve an array of purposes, including to catalyse an emotional response from readers and to raise awareness of biodiversity loss (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Bekoff and Bexell2011; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Xie, Huang, Li, Yuan and Liu2018). Independent of their original purpose, such media reports may provide useful information about the interactions of dogs with wildlife (Boydston et al., Reference Boydston, Abelson, Kazanjian and Blumstein2018). By compiling and examining such reports in combination with a review of the scientific literature, we present the first broad study of attacks by free-ranging dogs on the native mammal fauna of Iran.

Methods

We compiled information on the impacts of free-ranging dogs on mammals in Iran from news articles, social media reports and the scientific literature. We initially focused on 1999–2020, but given a paucity of early records the final dataset comprised reports and records for 2002–2020. The search was conducted during July 2019–February 2020 (i.e. records for 2020 comprise only the first 2 months).

For the scientific literature and traditional news media, we searched for articles on terrestrial mammals, both in English and Persian, that provided details on threats or status of a specific taxon or a group of taxa to check whether any interactions with dogs had been recorded. Articles were identified and sorted according to keywords and titles, and whether they covered threats or dogs. We used various keywords, including ‘dogs’ (and associated terms such as ‘herding dogs’ and ‘livestock guarding dogs’), ‘Iran’, ‘wildlife’, ‘attacks’ and ‘interactions’, and the family and species scientific and common names of medium and large mammals occurring in Iran. Given that the names of many small mammals are poorly known by the public, we did not search for each species of Rodentia, Eulipotyphla and Chiroptera. However, we did conduct searches using more generally recognized common terms such as ‘rodents’, ‘hedgehogs’ and ‘bats’. In a second stage, we also searched for each family name (e.g. dog attacks on felids) and if records existed we used a more targeted approach and added the name of all the species of that family (e.g. ‘cheetah’) in Persian. Searches were conducted using the Google search engine (Google, Mountain View, USA), with supplemental searches of Persian news websites that cover Iranian wildlife news (Iran Environment Watch, Animal Rights Watch, Islamic Republic News Agency).

For each of the affected mammalian species we recorded information, where available, on the IUCN regional Red List status, approximate location, protection level of the area (National Park, Wildlife Refuge, Protected Area or No-Hunting Area), province, village, date, age class of the wildlife species, source, and the status of the animal victim (dead, injured and/or rescued). From each report we also attempted to discern whether the case may have involved scavenging by dogs rather than predation, and any details of the number of dogs involved, and of the ownership of the dog(s). The status of dog ownership was attributed based on information gleaned from each article or post and from any supplemental photographs. We classified dogs as hunting dogs (if present with apprehended poachers), herding dogs or livestock guarding dogs (if dogs with collars were seen associated with herders or livestock) and unowned or feral dogs (if documented or reported as stray dogs in remote natural landscapes or in the core of protected areas).

We collected information from social media by searching for reports in Persian on free-ranging dog attacks on mammals posted online in Iran. We examined Instagram (Facebook, Menlo Park, USA) and Telegram (Telegram Messenger, London, UK) given their popularity in Iran and their allowance for the provision of photographs, which we could use to assess the details of interactions. We began by searching within the social media applications with keywords (as above) and supplemented this by using the Google search engine to identify reports in these social media applications. Searches in Google often yielded links to Instagram postings if the keywords appeared in the posts. For Telegram we only searched through its search box and environmental news channels (e.g. Iran Environment Watch).

Results

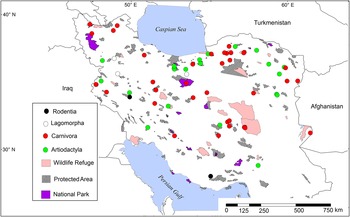

We compiled a total of 160 records of free-ranging dog attacks on 18 large mammalian species (Supplementary Table 1), of which 79 were collected from scientific articles, seven from Instagram, seven from Telegram and 67 from news websites. In 133 cases the year of the interaction was reported, and 95% of these cases occurred during 2010–2020. The interactions occurred in 22 provinces, with most incidents (116; 73%) reported from locations within or around protected areas under the management of the Iranian Department of Environment (Fig. 1). The central provinces accounted for the greatest number of reports of attacks (Yazd, 41; Semnan, 12; Tehran, 5; Markazi, 2; 38% overall) followed by the western provinces (Kermanshah, 11; Kordestan, 5; West Azarbaijan, 4; 13% overall). Within these settings, 60 cases occurred in Protected Areas (38%), seven in National Parks (4%), three in Wildlife Refuges (2%), and 12 in No-Hunting Areas (8%). Of the remaining 78 cases, 44 (28%) occurred in unprotected areas and 34 (21%) in landscapes for which the protected status was unreported.

Fig. 1 Iran, indicating wildlife refuges, national parks and protected areas, and the locations where dogs had been reported to kill, chase or injure medium and large mammals (Artiodactyla, Rodentia, Lagomorpha and Carnivora) during 2002–2020. Interactions were classified as a function of the taxonomic order of the wild mammal species.

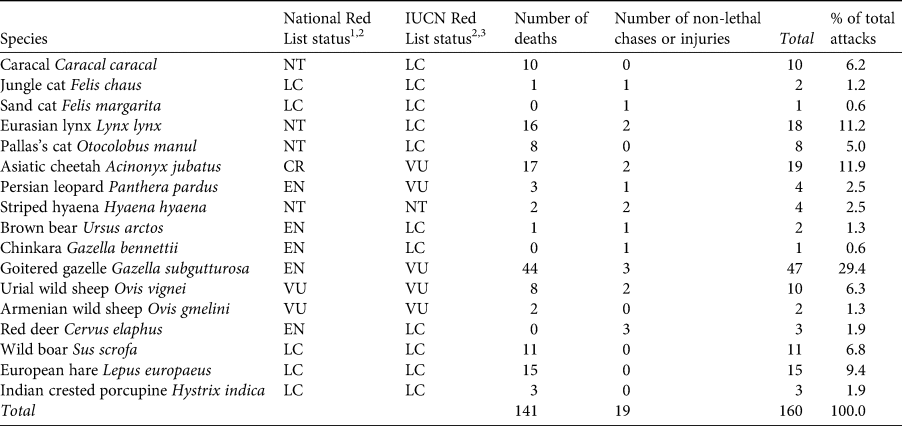

Across all reports, 68 focused on interactions of dogs with Carnivora (nine species), 74 with Artiodactyla (six species), three with Rodentia (one species) and 15 with Lagomorpha (one species) (Table 1). Of the interactions with Carnivora and Artiodactyla, most records referred to attacks on Felidae (39%, 62 reported interactions with seven species) and Bovidae (38%, 60 interactions with four species). We did not locate any records pertaining to interactions with the Persian onager Equus hemionus onager or with native canid species. Among attacked species, five were identified as globally threatened according to IUCN and eight were considered as nationally threatened (Yusefi et al., Reference Yusefi, Faizolahi, Darvish, Safi and Brito2019).

Table 1 Number of incidents of dead and chased or injured individuals of 17 mammal species attacked by free-ranging dogs in Iran during 2002–2020, determined from social and traditional media and the scientific literature, with their national and IUCN Red List status.

1 From Yusefi et al. (Reference Yusefi, Faizolahi, Darvish, Safi and Brito2019).

2 LC, Least Concern; NT, Near Threatened; VU, Vulnerable; EN, Endangered; CR, Critically Endangered.

3 From IUCN (2021).

Of the 160 attacks on mammals by free-ranging dogs, 141 (88%) resulted in the killing of the mammals involved, and the remaining incidents involved dogs chasing or injuring mammals but not the immediate death of the animal (Table 1). Of these 141 incidents, 90 reported an age class for the killed mammal: in 62 incidents (69%) the killed mammals were adults, and the remainder were reported as immature.

In 91 cases (57%) it could be determined that the free-ranging dogs were owned (hunting dogs, 36; livestock guarding dogs, 55), although the owners lacked sufficient control over the dogs to avert the incidents. In 69 other cases, dogs appeared to be unowned. Attacks by hunting dogs (36 cases) were generally attributed to hunting by poachers. Attacks typically involved a pack of dogs (Table 2), with the number of dogs involved reported for 75 cases. Of these, all but three cases reported > 1 dog. In the 40 cases where a pack size was reported, the mean pack size was 2.9 ± SD 1.2.

Table 2 Number of dogs reportedly involved in 160 attacks on wildlife in Iran.

1 Exact number not reported.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that free-ranging dogs have the potential to be a concern for the management of Iran's threatened mammals, as observed in other countries (Butler et al., Reference Butler, du Toit and Bingham2004; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dickman, Glen, Newsome, Nimmo and Ritchie2017; Home et al., Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a). Although domestic dogs are typically considered a commensal species by the general public and are rarely considered to interact with wild mammals, there is increasing recognition by ecologists that in many landscapes free-ranging dogs should be considered an invasive species (Home et al., Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a) or a species that reflects the breadth of human-associated edge effects (Soto & Palomares, Reference Soto and Palomares2015). Therefore, and given their potential impacts on Iranian wildlife, there is a need to consider and quantify further the interactions of free-ranging dogs and wildlife populations of conservation concern. The list we provide here is thus the first step towards identifying priority species and regions in Iran for further, detailed investigation. Our findings also underscore the need to identify ways to manage free-ranging dogs that reflect Iranian societal valuations of dogs.

Most of the target species were Artiodactyla and Carnivora, and, of these, threatened species such as the Asiatic cheetah and goitered gazelle Gazella subgutturosa subgutturosa comprised the majority of reports. It is possible that the high number of reports of attacks on threatened taxa reflects public recognition of the conservation value of these species. On the other hand, a lack of reports for species such as wild canids or Perissodactyla, which have been noted in other settings to be attacked by dogs or to perceive dogs as predators (e.g. Vanak et al., Reference Vanak, Thaker and Gompper2009; Sawant, Reference Sawant2018), is suggestive of reporting biases if one assumes such interactions are similarly likely in Iran. Such reporting biases may also occur when small prey are hunted, and could suggest an underreporting of the impacts of free-ranging dogs on more common, less observable (e.g. nocturnal), or less charismatic taxa. For example, the wild mammals consumed by dogs in an Indian grassland ecosystem were principally rodents and hares, yet these mammals comprised just 11% of identified cases (Vanak & Gompper, Reference Vanak and Gompper2009b).

Nonetheless, the majority of the 18 species attacked are categorized as threatened nationally (Fig. 2). For example, the Asiatic cheetah is already declining as a result of collisions with vehicles and disturbance by grazing livestock (Farhadinia et al., Reference Farhadinia, Hunter, Jowkar, Schaller, Ostrowski, Marker, Boast and Schmidt-Küntzel2018). For such species, negative direct impacts of free-ranging dogs through predation or chasing, and indirect interactions through resource competition (such as kleptoparasitism), can hinder conservation (Mohammadi & Kaboli, Reference Mohammadi and Kaboli2016; Farhadinia et al., Reference Farhadinia, Hunter, Jourabchian, Hosseini-Zavarei, Akbari and Ziaie2017, Reference Farhadinia, Hunter, Jowkar, Schaller, Ostrowski, Marker, Boast and Schmidt-Küntzel2018; Moqanaki & Cushman, Reference Moqanaki and Cushman2017; Mohammadi et al., Reference Mohammadi, Almasieh, Clevenger, Fatemizadeh, Rezaei and Jowkar2018). Thus, dogs are recognized as a primary threat for several species in Iran, including caracal Caracal caracal, Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx, Pallas's cat Otocolobus manul, sand cat Felis margarita, Southwest Asian badger Meles canescens and goitered gazelle (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Habibi Pour and Khormizi2013; Joolaee et al., Reference Joolaee, Moghimi, Ansari and Ghoddousi2014; Farhadinia et al., Reference Farhadinia, Moqanaki, Hosseini-Zavarei and Sharbafi2016; Ghadirian et al., Reference Ghadirian, Akbari, Besmeli, Ghoddousi, Hamidi and Dehkordi2016; Moqanaki et al., Reference Moqanaki, Farhadinia, Tourani and Akbari2016; Mousavi et al., Reference Mousavi, Moqanaki, Farhadinia, Sanei, Rabiee and Khosravi2016; Proulx et al., Reference Proulx, Abramov, Adams, Jennings, Khorozyan, Rosalino, Proulx and Do Linh San2016).

Fig. 2 Number of attacks on mammals by free-ranging dogs in Iran during 2002–2020, by the national IUCN Red List status of the attacked species (Red List assessments from Yusefi et al., Reference Yusefi, Faizolahi, Darvish, Safi and Brito2019).

Of particular concern is the large number of attacks by free-ranging dogs reported to have occurred either within or adjacent to protected areas. This pattern of dog movements into protected areas has also been reported elsewhere. For example, Home et al. (Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a) found that 48% of attacks identified in India from online and print media surveys occurred in protected areas. In Brazil, Bianchi et al. (Reference Bianchi, Olifiers, Riski, Gouvea, Cesário and Fornitano2020) used camera trapping to identify the presence of free-ranging dogs in 11 of 14 surveyed protected areas. Such dogs do not typically inhabit only the protected areas. Rather, they are owned by people who live near protected areas (Soto & Palomares, Reference Soto and Palomares2015), and enter protected areas either accompanying people or to hunt wildlife. Grazing outside core areas is allowed in Iranian protected areas, and this may facilitate the use of these landscapes by dogs (Majnoonian, Reference Majnoonian2000).

Although highly variable between countries, globally a high proportion of dog owners in rural areas allow their dogs to roam free (Gompper, Reference Gompper and Gompper2014b). This is also the case in Iran. Dogs that have owners (e.g. ranchers, herders or people living in nearby farms or villages) may nevertheless roam through natural landscapes, including within protected areas. In this regard, we emphasize that responsible dog ownership that focuses on population and behaviour control via veterinary care (including neutering and vaccination where appropriate), restricts dog movement, and improves dog husbandry (including adequate feeding and shelter) can reduce interactions with wildlife (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Bland, Forrester, Baker-Whatton, Schuttler and McShea2016; Villatoro et al., Reference Villatoro, Naughton-Treves, Sepúlveda, Stowhas, Mardones and Silva-Rodríguez2019). More specifically with regard to wildlife conservation in Iran, various approaches could be used to reduce the predation of wildlife by dogs: (1) training programmes for herders and owners, (2) enhanced law enforcement focusing on restriction of the movements of free-ranging dog and reduced presence of dogs in protected areas, (3) increased consideration of best practices for removal of unowned dogs from protected areas by either capture and transport to animal shelters or, if necessary, by culling, (4) improved approaches to solid waste management, especially adjacent to protected areas, and (5) enhanced cooperation between various organizations such as the Department of Environment, municipalities, NGOs and local Health Ministry offices that could oversee or assist in addressing this problem.

Each of these approaches has been used to address dog–wildlife conflicts in a variety of settings, but with variable success. For example, capture–neuter–vaccinate–release is sometimes used in an effort to reduce dog populations (Schurer et al., Reference Schurer, Phipps, Okemow, Beatch and Jenkins2014) but this method can be ineffective especially in areas of high dog densities (Winter, Reference Winter2004; Longcore et al., Reference Longcore, Rich and Sullivan2009; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dickman, Glen, Newsome, Nimmo and Ritchie2017). Thus a more holistic approach is often necessary, involving population control, vaccination, adequate feeding and control of free-ranging behaviour by dog owners, and potentially solutions such as removal of unowned and feral dogs from areas of conservation concern (Home et al., Reference Home, Bhatnagar and Vanak2017a). A single method is unlikely to provide a solution in all regions of Iran. In some cases, for example, lethal removal programmes may face public resistance (Young et al., Reference Young, Olson, Reading, Amgalanbaatar and Berger2011; Villatoro et al., Reference Villatoro, Naughton-Treves, Sepúlveda, Stowhas, Mardones and Silva-Rodríguez2019). In other regions, the setting of the protected area may make particular management approaches more difficult to implement. Some protected areas are located on the outskirts of cities, which given the high density of dogs in suburban settings in Iran, augments the risk of incursions by free-ranging dogs (e.g. Sorkhe Hesar National Park and Protected Area in Tehran). Thus, the issues associated with controlling the impacts of dogs must be addressed, at least in part, regionally (Hiby & Hiby, Reference Hiby, Hiby and Serpell2016). Nonetheless, the fact that wildlife predation by free-ranging dogs has been reduced in other settings indicates this could also be achieved in Iran.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, or commercial or not-for-profit sectors. We are grateful to E. Moqanaki, K. Baradarani, A. Ammarloei and A. Beigpour for providing additional information on cases. Furthermore, we are thankful of M.S. Farhadinia, A. Rezaeian and N. Samadzadeh for insightful ideas and comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We thank two anonymous reviewers and the Editor for their helpful suggestions.

Author contributions

Study design and data collection: DN; data analysis and writing: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.