In recent decades, a growing number of epidemiological studies and governmental assessments have shown interest in the evaluation of food insecurity at the household level. Worldwide research was particularly boosted after the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals, the primary goal of which was to reduce by half the proportion of people living on less than $US 1·25 per day and suffering overt hunger between 1990 and 2015( 1 ). The increase in food prices due to the recent global economic crisis of 2008–2009 also reinforces the importance of research as a foundation for redirecting social policies to fight hunger in many countries( Reference Pérez-Escamilla 2 ).

Most of the knowledge has come from epidemiological studies. These have focused mainly on the magnitude, risk factors and consequences of household food insecurity (HFI), as well as assessments of intervention programmes aimed at reducing the effect of food insecurity. More recently, there has been a growing recognition that HFI is a difficult construct to measure due to conflicting definitions implying different forms of operationalization( Reference Bickel, Nord and Price 3 – Reference Coates 5 ).

For many years, HFI has been assessed by indirect methods, such as food availability, purchasing power, consumption profile and anthropometric measurements, and the main objective was to quantify the number of individuals in a situation of food shortage or even outright hunger( Reference Kepple and Segall-Corrêa 4 ). As of the end of the 1970s, it became clear that indirect methods were insufficient to cover all dimensions of the food insecurity construct. One of the issues raised was the need to establish appropriate indicators to identify and monitor food insecurity in intervention studies( Reference Pereira and Santos 6 ). Several initiatives were launched, and different tools were proposed for measuring the perception and/or the experience of families suffering from food insecurity( Reference Kepple and Segall-Corrêa 4 ). Yet, despite all efforts to devise direct measures, a variety of methods and the absence of a reference standard for assessing HFI have so far precluded a consensus as to which should be the measure of choice to operationalize the concept in epidemiological studies. The purpose of the present study was to provide a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature published in scientific journals, with an aim to identify and scrutinize direct instruments to measure HFI, in particular the experience-based household food security scales. Several features were focused on, i.e. the scale’s origin (country, place and language), main characteristics (number of items and type of response options), uses (in applied research and cross-cultural studies) and psychometric background (number and types of studies/assessed properties). This account may help in identifying the best available scales for use in decision making and research settings and/or as an aid in developing new ones.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in three sources: (i) a worldwide electronic database, MEDLINE (consulted through PubMed); and two comprehensive Latin American databases, (ii) LILACS and (iii) SciELO. There was no limitation on the period of publication. A search was performed in June 2011 by a single reviewer, using the following descriptors: (‘food insecurity’ OR ‘food security’) AND (‘questionnaires’ OR ‘scales’ OR ‘validity’ OR ‘reliability’). This descriptor was also used for the respective Portuguese and Spanish versions. Thereafter, two reviewers independently scrutinized the reference sections of all identified psychometric and review articles, with an aim to detect additional scientific papers not spotted in the first search round. This approach also allowed identification of some government reports introducing the main characteristics of the scales found in the first stage of the search. All of the references were filed and handled using EndNote X6™.

Selection criteria

Only articles published in English, Spanish or Portuguese were accepted. These had to approach the subject through direct tools to measure different aspects of HFI, such as quantity, quality and/or access to food. Monographs, dissertations, academic theses, government and institutional reports, summaries of scientific events, books and articles merely expressing points of view/opinions of experts were not eligible and thus barred from further scrutiny.

The selection of the articles of interest involved a thorough scrutiny of the titles and abstracts, and was carried out by the independent reviewers mentioned before. The articles were then classified according to whether they: (i) definitely met the inclusion criteria; (ii) could possibly meet the inclusion criteria, but required full reading for confirmation; or (iii) definitely did not meet the criteria and should, therefore, be excluded. An inter-observer reliability evaluation was carried out using the κ coefficient with quadratic weighting as estimator( Reference Fleiss 7 , 8 ). Disagreements between the reviewers were further discussed with the other authors and settled by consensus.

Classifying articles

The same reviewers independently read all articles in full. These were classified into six non-mutually exclusive groups: (i) articles that made use of the measuring instruments for HFI in epidemiological studies; (ii) articles focusing on cross-cultural adaptation processes; (iii) psychometric studies; (iv) articles presenting new instruments; (v) review articles; and (vi) key documents used as guidelines in the development process of the instrument.

Data extraction

Extracting information from the selected articles was effected by the independent reviewers, using a purposefully designed form. The following information was sought: (i) title/name of the HFI measurement tool; (ii) the first reference introducing the instrument (authors and year of publication); (iii) country where the instrument was devised; (iv) language; (v) number of component items; (vi) types of response options; and (vii) the number of articles using the instrument in epidemiological studies and/or focusing on cross-cultural adaptation and/or evaluating psychometric properties. One of the reviewers further detailed the latter feature in tandem with two epidemiologists experienced in psychometrics. The following information was sought: (i) place and year of the study; (ii) number of items actually used in a particular analysis; (iii) sample size; (iv) method of application and reference period; and (v) psychometric features evaluated, the estimators used and respective results.

The following classification was used to synthesize information on the reliability of scales: intra-observer (or test–retest) reliability, inter-observer reliability and internal consistency( Reference Streiner and Norman 9 ). Validity studies were classified according to Streiner and Norman( Reference Streiner and Norman 9 ) and Terwee et al.( Reference Terwee, Mokkink and Knol 10 ) in four types: (i) face or content validity; (ii) structural (dimensional) validity; (iii) criterion or concurrent validity; and (iv) construct validity. Only measurement tools with three or more items were included( Reference Brown 11 ).

Results

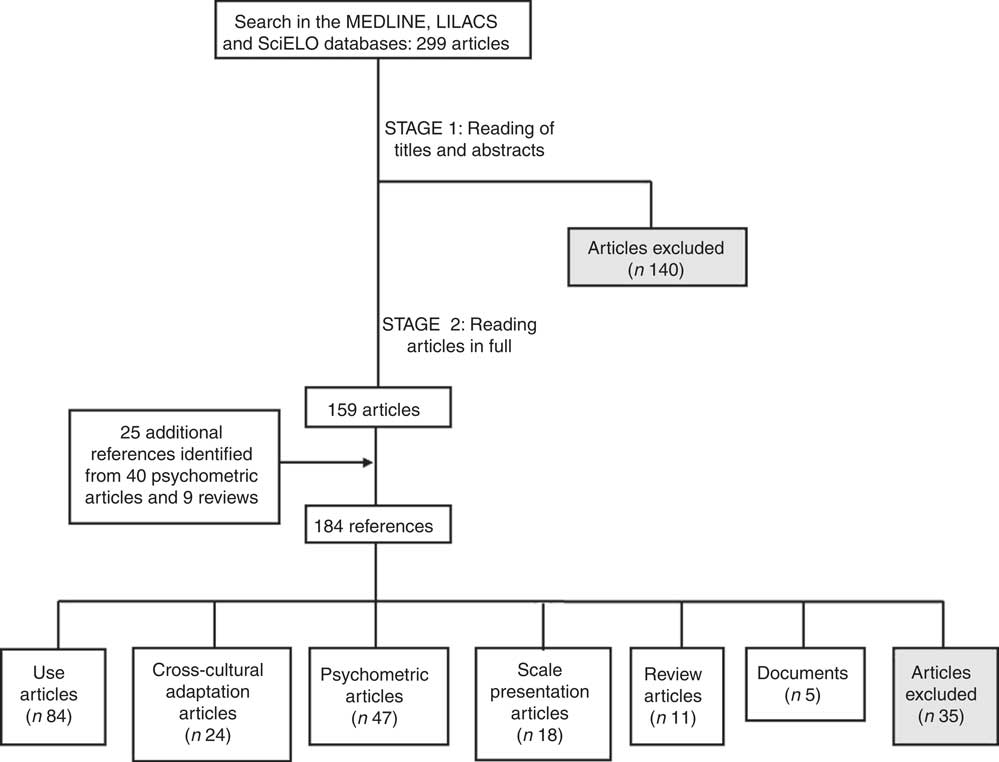

As presented in Fig. 1, the first stage of the systematic review identified 299 references published from 1979 to the date of search; 279 (93·3 %) were indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed. Of the total, 140 had to be excluded since they did not fulfil the eligibility criteria. This evaluation stage met with substantial agreement between the reviewers according to Shrout’s criteria( Reference Shrout 12 ), showing a weighted κ of 0·853 (95 % CI 0·777, 0·917).

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of the systematic review

Once reading the remaining 159 articles in full (stage 2), another thirty-five were further excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. This stage also involved consulting the reference sections of forty psychometric articles and nine reviews, which added another twenty-five references. Five of those were official documents concerning the development process of some scales.

Characteristics of the instruments

Twenty-four instruments were identified in the 184 references evaluated. Their main features are found in Table 1. Although the majority (58·3 %) were devised and developed in the USA( Reference Bickel, Nord and Price 3 , Reference Kendall, Olson and Frongillo 13 – Reference Chavez, Telleen and Kim 23 ), research groups in countries like Canada( Reference McIntyre, Glanville and Officer 24 ), Venezuela( Reference Lorenzana and Sanjur 25 ), Colombia( Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Melgar-Quiñonez and Nord 26 ), Costa Rica( Reference Gonzalez, Jimenez and Madrigal 27 ), Burkina Faso( Reference Frongillo and Nanama 28 ), Kenya( Reference Faye, Baschieri and Falkingham 29 ), Iran( Reference Zerafati Shoae, Omidvar and Ghazi-Tabatabaie 30 ), Bangladesh( Reference Frongillo, Chowdhury and Ekstrom 17 , Reference Coates, Wilde and Webb 31 ) and Indonesia( Reference Studdert, Frongillo and Valois 32 ) also took initiatives. Most of the instruments were originally conceived in English, are brief, and hold dichotomous responses.

Table 1 General characteristics of detection instruments for household food insecurity identified in the present review and their respective publicationsFootnote * , Footnote †

CCA, cross-cultural adaptation.

* The instruments that originated from a process of CCA of instruments devised in other cultural contexts and that maintained the same number of items as the original instrument were considered as linguistic/semantic variants of these. On the other hand, the ‘modified’ versions of the instruments had a number of items different from those in the original instruments. Some modified versions received new names, whereas others kept the name of the original scale. In the latter case, it was often to put the name of the original scale followed by the word, ‘modified’.

† For the scales that were modified and presented in more than one study, the older or oldest publication was considered as the original reference.

‡ Some of the linguistic variants have not gone through a formal CCA process.

§ Only one study was found referring to the presentation of the HFSB_b scale.

The instruments mostly found in the scientific literature were the Core Food Security Measurement/Household Food Security Survey Module (CFSM/HFSSM; sixty-nine articles), the HFSSM Six-Item Short Form (HFSSM-6SF; seventeen articles), the Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (a) (R/CSm_a; fifteen articles) and the Self-Perceived Household Food Security Scale (SPHFSS; ten articles). Besides the respective original instruments, modified versions of the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project (CCHIP), CFSM/HFSSM, HFSSM-6SF, Food Insecurity Questions of NHANES III (NHANES III_FIQ) and Radimer/Cornell Scale (R/CS) were also detected.

The instruments hold different terms/nomenclatures and underlying concepts. Terms mostly used were: (i) household food insecurity (eight instruments); (ii) food insecurity (seven instruments); (iii) hunger (six instruments); (iv) food security (four instruments); (v) food insufficiency (two instruments); (vi) food insecurity past (one instrument); and (vii) household hunger (one instrument). The concepts of food insecurity, household food insecurity, hunger and food security used by most scales were outlined by Anderson( Reference Anderson 33 ). The concept of household hunger that stood at the foundation for drafting the R/CS refers to three central issues: food depletion, food unsuitability and food anxiety( Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell 34 ). Moreover, the issue of scarce financial resources was at the core in nearly all of the instruments’ development processes.

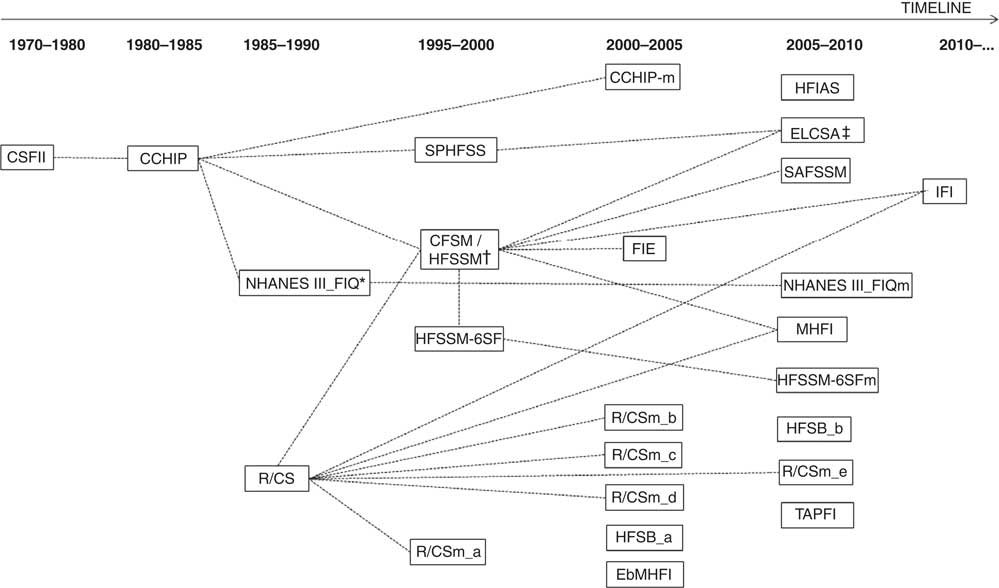

Figure 2 shows the periods in which the instruments emerged, as well as the links between them. As early as 1977, the Agricultural Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) pioneered the food sufficiency question in the Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals (CSFII). This question fed into the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), which carried a variant of it along with several items from the CCHIP. This scale was developed in the early 1980s in the USA by the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project( Reference Wehler, Scott and Anderson 35 ). The CCHIP intended to evaluate the prevalence of hunger among low-income families with children up to the age of 12 years. New initiatives from US government institutions and academia subsequently gained prominence. Driven by the NHANES III and Cornell University, this movement culminated in the development of important indicators for the area. NHANES III enabled an instrument with questions related to the sufficiency of food and hunger to be used at the national level( Reference Briefel and Woteki 36 ). At the same time, researchers from Cornell University proposed an instrument based on women’s reports of their perception and experience of hunger, as well as their difficulties in obtaining adequate food( Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell 34 , Reference Radimer, Olson and Greene 37 ).

Fig. 2 Record of the development of the existing measuring instruments for detection of household food insecurity. Note: CSFII, Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals; CCHIP, Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project; NHANES III_FIQ, Food Insecurity Questions of NHANES III; R/CS, Radimer/Cornell Scale; SPHFSS, Self-Perceived Household Food Security Scale; CFSM/HFSSM, Core Food Security Measurement/Household Food Security Survey Module; HFSSM-6SF, HFSSM Six-Item Short Form; R/CSm_a, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (a); CCHIP-m, Modified CCHIP; FIE, Food Insecurity by Elders; R/CSm_b, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (b); R/CSm_c, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (c); R/CSm_d, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (d); HFSB_a, Household Food Security of Bangladesh (a); EbMHFI, Experience-Based Measurement of Household Food Insecurity; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; ELCSA, Latin American Food Security Measurement Scale; SAFSSM, Self-Administered Food Security Survey Module for Children Aged 12 and Older; NHANES III_FIQm, Modified Food Insecurity Questions of NHANES III; MHFI, Measurement of Household Food Insecurity; HFSSM-6SFm, Modified HFSSM Six-Item Short Form; HFSB_b, Household Food Security of Bangladesh (b); R/CSm_e, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (e); TAPFI, Tool to Assess Past Food Insecurity; IFI, Items of Food Insecurity; USDA, US Department of Agriculture. *NHANES III_FIQ are questions related to food insufficiency due to lack of income used NHANES III. The CCHIP was used in its development process, along with questions about food insecurity arising from the USDA Food Consumption Research. †In 2000, the USDA published the Guide to Measuring Household Food Security – Revised 2000 in which the CFSM is an update. This version was renamed HFSSM. CFSM and HFSSM must be considered as the same instrument because they contain exactly the same items. The only difference is in order of administration of the questions. ‡The ELCSA was developed from the linguistic and semantic variants of SPHFSS (Colombian Food Security Scale) and the Brazilian version of CFSM/HFSSM

The stimulus generated by research and publications in the 1980s, pushed by a growing awareness for the need to develop new measurement tools to address food insecurity adequately, bore fruit early in the next decade. The Conference on Food Security Measurement and Research was one of the most significant initiatives in this period. The event convened many researchers and experts in the area and sought to develop a consensus on a conceptual basis for a measure of food insecurity and hunger to be used throughout the USA and to debate how to operationalize this concept( 38 ). A year later, the USDA opted to measure food insecurity through a new instrument, the CFSM( Reference Price, Hamilton and Cook 39 ). This measurement tool had the CCHIP( Reference Wehler, Scott and Anderson 35 ) and the R/CS( Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell 34 , Reference Radimer, Olson and Greene 37 , Reference Nord and Hopwood 40 ) at its core, as well as other scales focusing on the experience of HFI caused by limitations of economic resources in meeting basic needs of the individual and families( Reference Carlson, Andrews and Bickel 41 ).

Despite the efforts, it was not until the 2000s that the development of most scales occurred. Besides the development of entirely new instruments, adaptation of existing ones also took place. This was the case with the CFSM scale. Updated in 2000 by the Food and Nutrition Service of the USDA, it became known as the HFSSM( Reference Bickel, Nord and Price 3 ). Since then, the CFSM and HFSSM are recognized as one because they hold exactly the same items. They differ only with respect to the order with which the questions are presented( Reference Bickel, Nord and Price 3 ). The CCHIP, R/CS, CFSM/HFSSM form the base of the majority of the instruments available nowadays.

Psychometric properties of the instruments

Table 2 summarizes forty-seven studies evaluating the psychometric properties of the instruments. The CFSM/HFSSM (eighteen articles) is the most often evaluated instrument according to the consulted peer-reviewed literature. The SPHFSS follows with seven. The HFSSM-6SF shows five studies. Six out of twenty-four identified instruments did not have any psychometric study: the Modified CCHIP (CCHIP-m); the Household Food Security of Bangladesh (a) (HFSB_a); the Household Food Security of Bangladesh (b) (HFSB_b); the Modified HFSSM Six-Item Short Form (HFSSM-6SFm); the Modified Food Insecurity Questions of NHANES III (NHANESIII-FIQm); and the Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (c) (R/CSm_c).

Table 2 Psychometric evidence of the epidemiological instruments measuring household food insecurity

CFSM/HFSSM, Core Food Security Measurement/Household Food Security Survey Module; SPHFSS, Self-Perceived Household Food Security Scale; HFSSM-6SF, HFSSM Six-Item Short Form; R/CSm_a, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (a); R/CSm_b, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (b); R/CSm_d, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (d); R/CSm_e, Modified Radimer/Cornell Scale (e); CCHIP, Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project; R/CS, Radimer/Cornell Scale; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; ELCSA, Latin American Food Security Measurement Scale; EbMHFI, Experience-Based Measurement of Household Food Insecurity; MHFI, Measurement of Household Food Insecurity; IFI, Items of Food Insecurity; TAPFI, Tool to Assess Past Food Insecurity; FIE, Food Insecurity by Elders; NHANES III_ FIQ. Food Insecurity Questions of NHANES III; SAFSSM, Self-Administered Food Security Survey Module for Children Aged 12 and Older; GOF, goodness of fit; FI, food insecurity; GLM, general linear model; IRT, Item Response Theory; 2PL, the two-parameter model; HFI, household food insecurity; DIF, differential item functioning; EFA, exploratory factor analysis; CHFSS, adapted Colombian Household Food Security Survey; SEM, structural equation model; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value.

*‘?’ sign means that the study did not explicitly discriminate the number of items on the scale used. The same number of items as in the original version was thus considered.

The psychometric studies date back to the 1990s and have been mostly carried out in the USA. The majority are restricted to some aspects of the reliability and validity. Internal consistency estimated through Cronbach’s α coefficient has been the most analysed facet of reliability. A few studies also report results from structural (dimensional) and construct validity evaluations.

In all, the CFSM/HFSSM, SPHFSS and HFSSM-6SF have thus far been the most thoroughly assessed instruments. Their psychometric evaluations were mostly carried out in the last 15 years or so. According to the reviewed literature, the CFSM/HFSSM and HFSSM-6SF have been studied in many countries worldwide, whereas the SPHFSS only in Latin America (Colombia and Venezuela). Internal consistency has been mostly supported; eleven studies on the CFSM/HFSSM and HFSSM-6SF showing Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0·73 to 0·95, and six studies on the SPHFSS with α varying from 0·82 to 0·94. A few studies also assessed other facets of reliability, such as test–retest reliabilities (CFSM/HFSSM: κ=0·66; r=0·75 and SPHFSS: r=0·98).

All three instruments had some form of construct (structural) validity supported. Regarding the CFSM/HFSSM, among the fourteen validity studies detected in the eligible literature, nine assessed structural validity. Eight of those employed a complete Rasch analysis, which on the whole supported a one-dimensional structure and the appropriateness of the component items. Six out of seven psychometric studies on the SPHFSS evaluated structural validity employing exploratory factor analyses, Rasch analyses and/or full structural equation models. These studies suggested a two-factor structure. Convergent validity was also sustained in all three instruments, with several studies showing some association between the food insecurity measure and predictor variables as expected. Moreover, acceptable screening capability of the HFSSM-6SF was demonstrated by two criterion validity studies, which showed sensitivities ranging from about 85 % to almost 100 %, and specificities from just below 80 % to nearly 100 %.

Discussion

Since the end of the 1970s, efforts have been directed to define better and characterize HFI worldwide. Triggered by the pioneering strategies proposed in the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project( Reference Wehler, Scott and Anderson 35 ) and the Radimer research group at Cornell University( Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell 34 , Reference Radimer, Olson and Greene 37 ), and driven by the recognition of the Human Right to Adequate Food( 42 ) and the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals( 1 ), this movement reached different continents in the decades that followed. The large number of competing instruments is testimony to the commitment to this quest.

The common feature is that all instruments were developed from food insecurity and hunger concepts linked to a lack of access to food due to scarce financial resources. Questions (items) related to other aspects of the construct, such as food safety, have hardly been addressed so far( Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson 43 ).

A feature found on some instruments relates to different forms of operationalization, which takes into account whether or not a child is present in the household (e.g. CCHIP, SPHFSS, CFSM/HFSSM, HFSB_b, Latin American Food Security Measurement Scale (ELCSA), Measurement of Household Food Insecurity (MHFI), Items of Food Insecurity (IFI), Tool to Assess Past Food Insecurity (TAPFI) and R/CS). Adapting a version for families with children has been justified by the specific nutritional needs in this age group in terms of quantity, quality and regularity of food supply. The same rationale may also apply to the elderly. However, despite research addressing food insecurity in this age group, there is only one particular measurement tool so far available in this respect( Reference Nord 44 – Reference Lee, Fischer and Johnson 46 ). Maybe it would be timely to invest in the development of more food insecurity instruments specially tailored for this fast growing sub-population. Elderly persons often have distinct metabolic and nutritional requirements, and many find themselves in unwelcoming social contexts. Besides food-access problems due to inadequate resources to purchase food, there are also logistical problems, such as getting to food stores or even preparing meals.

There were discernible methods comprising the evaluation processes. Studies covered various countries, settings (household, health services and educational institutions) and population groups (women, adolescents and children, among others). They also used different forms of application (self-application, interview, telephone) and recall periods (1 to 12 months). This array of assessments in somewhat diverse contexts highlights the efforts in attaining cross-cultural comparisons( Reference Streiner and Norman 9 ).

Still, despite this ambitious and positive scenario, not many instruments underwent strict testing according to the evaluated peer-reviewed literature. Of all twenty-four instruments identified, only one (CFSM/HFSSM) has been evaluated through fifteen or more psychometric studies. Another instrument had seven studies (SPHFSS), two had five studies (HFSSM-6SF), yet four were tested only twice, and another eleven just once. In addition, most of these studies repeatedly explored features assessed in preceding ones (e.g. reliability/internal consistency), thus failing to shed new light on many other important psychometric features. Important properties, such as the sustainability of the theoretically proposed dimensional structure; item reliability and absence of measurement error correlations; factor-based convergent and discriminant validity; scalability; item positioning (difficulty/intensity) vis-à-vis the latent trait; and the evaluation of measurement invariance (heterogeneity/item differential functioning), have not been extensively scrutinized( Reference Brown 11 , Reference Sijtsma and Molenaar 47 – Reference Reichenheim, Hökerberg and Moraes 50 ).

In fairness, there are studies addressing some dimensional aspects, but most are restricted to exploratory factor analyses and on the whole barely cover the confirmatory-type scrutiny as is the case of the mentioned properties. As understood from the evidence stemming from the literature found in peer-reviewed scientific journals, the exceptions are the CFSM/HFSSM and to a lesser extent the SPHFSS and the HFSSM-6SF. Not only have these instruments been tested more frequently, but their history comprises several evaluations suggesting the tenability of the underlying properties.

In this regard the CFSM/HFSSM stands out prominently, with several Rasch analyses disclosing the good performance of the component items, while also disclosing subtleties such as the difficulty in calibrating the instrument in families with and without children. In fact, the adequacy of the CFSM/HFSSM may also be identified in the respective institutional and/or government literature. Several technical reports published by the USDA since 1995 consistently provide substantiation to the reliability and validity of the instrument( Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson 43 , Reference Ohls, Radbill and Schirm 51 – 53 ). For instance, a report by Hamilton et al. (Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson1997) found the food security scale to have good reliability, including good content validity and good construct validity( Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson 43 ). Their report also showed expectedly high correlations between food security measured by the scales under scrutiny and weekly food expenditures per household, annual household income and income relative to the poverty line( Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson 43 ). More recently, too, a study by Nord on the potential technical enhancements to the CFSM/HFSSM using Rasch analysis showed favourable results regarding item severity parameters in both adult and child food security scales( Reference Nord 54 ). Valuable institutional information may also be found in regard to recent offshoots of the CFSM/HFSSM; for instance, the ELCSA. Reports showed adequate internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s α coefficient in the range of 0·91–0·96, and as anticipated, strong correlations between the scale and several sociodemographic variables like poverty, housing conditions and access to public services( Reference Melgar-Quiñonez 55 , Reference Segall-Côrrea, Álvarez-Uribe and Melgar-Quiñonez 56 ).

Regarding the assessment of other aspects of validity, and more specifically in relation to criterion validity, a challenge concerns the lack of agreement as to the standard to use. Some studies turned to other food insecurity scales as reference, especially the CFSM/HFSSM. This strategy may overestimate sensitivity and specificity because offshoot instruments usually have many items in common with the purported ‘gold standard’. This overestimation may have occurred in the studies of Connell et al.( Reference Connell, Nord and Lofton 18 ).

Although most studies assert that the psychometric properties have been confirmed (corroborated), this should be regarded with some caution. As pointed out above, some detailed research is still needed before a clear-cut consensus may be reached. A solid choice for a particular instrument demands guidance from in-depth sequential analyses; something that, as seen, is yet to be achieved concerning most of the measurement tools addressing food insecurity. Although there are a few clear frontrunners in this dispute, perhaps much could be gained from more and better evidence regarding the other instruments, as well. The greater the choice, the better the decisions that may follow.

The interpretation of the present study’s results requires perspective in the light of its limitations. Despite our effort to meet with rigour the inclusion criteria established for the review, missing out some articles may not be ruled out since the literature is bound to hold publications with positive results. However, in an attempt to minimize such a publication bias, we sought to scrutinize carefully the reference sections of all psychometric and review articles in order to locate those studies missed out by the employed algorithm-based search strategy. Likewise, language bias may not be ruled out since studies with positive and interesting results are more likely to be published in English, while those with negative or non-significant results tend to be published in other languages( Reference Sterne, Egger and Moher 57 , Reference Egger, Smith and Schneider 58 ). In order to lessen this possible language bias, we opted to broaden the linguistic scope beyond English by also including studies in Spanish and Portuguese.

The methodological option to restrict the review to peer-reviewed scientific journals published in PUBMED, LILACS and/or SciELO – and thus disregarding research reports, dissertations, theses and other sources not published in indexed journals – certainly narrowed the scope of the study. An ancillary search identified several government sources addressing some of the scales covered in this review (e.g. Brazil( Reference Segall-Corrêa, Escamilla and Sampaio 59 – 61 ), Canada( 62 ), Colombia( 63 , 64 ), USA( Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson 43 , Reference Ohls, Radbill and Schirm 51 , Reference Cohen, Nord and Lerner 52 ) and Iran( Reference Ghassemi, Kimiagar and Koopahi 65 , Reference Qasemi 66 )). Surely, a step forward would be to expand the approach by accounting for information arising from a wider institutional literature, not only by assessing hard evidence found in published media, but also through personal contacts with researchers and institutions proposing the scales. On a positive note, however, the current synthesis presents a favourable picture not withstanding the remaining gaps. As evolved up to now, some measurement tools (e.g. the CFSM/HFSSM and its variants and offshoots) are already apt in assisting researchers and decision makers in evaluating food insecurity.

Conclusion

The present study sought to provide detailed information about the extant experience-based HFI instruments used in most studies worldwide. From the twenty-four measurement tools identified, the CFSM/HFSSM, HFSSM-6SF and SPHFSS were the most frequently used and evaluated, holding the largest number of psychometric and applied studies conducted in different socio-economic and cultural contexts. Still, according to the peer-reviewed literature used here, these instruments and the others above of all would gain from further psychometric evaluations so that an array of not yet explored properties may be addressed. Despite these shortcomings, overall, one may conclude that current knowledge about the quality of the tools available to measure food insecurity is moving forward.

To reiterate, according to the state-of-the-art shown in the current evaluation, the CFSM/HFSSM and its linguistic variants may be recommended without much hesitation. However, as also pointed out earlier, few psychometric studies were found for most of the other scales. Initiatives intended to raise awareness about the need for psychometric assessments of existing scales would thus be encouraging. For instance, an interesting endeavour would be to establish a database repository encompassing all results from psychometric and utilization studies so that interested researchers could carry out their own psychometric analyses and/or use the scales for different purposes. Also of help would be to have any evidence so far disclosed in institutional and/or government reports, additionally published in peer-reviewed journals so that the findings and discussions on the different methods of food insecurity classification could be fully accessed and used by researchers in the field worldwide.

In concluding, we hope the present paper may serve as an incentive for further studies, given the importance of using reliable and valid instruments, not only in epidemiological research, but also as screening and decision-making tools to guide actions to address food insecurity at local and national levels.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: E.S.M. was partially supported by the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq; grant number 162030/2012-6). C.L.M. was partially supported by the CNPq (grant number 302851/2008-9). M.E.R. was partially supported by the CNPq (grant numbers 306909/2006-5 and 301221/2009-0). The CNPq had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: E.S.M. collaborated in designing the study, undertook the literature review, assisted in analysing the data and wrote the final draft of the manuscript. C.L.d.M. and M.E.R. designed the study, supervised the data collection process, undertook the analysis and collaborated in writing the final draft of the manuscript. M.M.L.A. collaborated in designing the study, undertook the literature review and assisted in analysing the data. R.S.-C. collaborated in designing the study and supervised the data collection process. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required for this study.