1. Introduction

In the southern Dutch province of North Brabant, an interesting language change is under way that may shed light on the social meaning of linguistic variation. One of the most distinctive Brabantish dialect features is the overt marking of lexical gender, in particular the adnominal masculine gender suffix -e(n) that precedes masculine singular nouns, for example ene man ‘a-m man.m’ and enen hond ‘a-m dog.m’, but en vrouw ‘a-f woman.f’ (e.g. Hoppenbrouwers Reference Hoppenbrouwers1990, De Schutter Reference De Schutter, Hinskens and Taeldeman2013).Footnote 1 This suffix is one of the features that distinguishes the dialect from Standard Dutch, as the latter does not mark the difference between masculine and feminine gender on adnominals (determiners and adjectives), for example een man (m) ‘a man’, een hond (m) ‘a dog’, and een vrouw (f) ‘a woman’ (in Standard Dutch). The linguistic form of the suffix, i.e. -e, -en or -n, depends on a phonological condition, as the so-called binding-n only precedes vowels or consonants h, b, d, t, for example enen ouwen hond ‘an-m old-m dog.m’ vs. ene goeie koning ‘a-m good-m king.m’.Footnote 2

It is widely known that grammatical gender systems may change over time (e.g. Tamminga Reference Tamminga2013, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019). However, the Brabantish gender suffix nowadays shows a remarkable shift in which its grammatical function seems to be losing ground in favor of a stylistic function. It can, because it is recognized as belonging to Brabantish and functions as a shibboleth. Shibboleths are distinctive characteristics that are ‘enregistered’ and therefore easily recognizable. According to Agha (Reference Agha2007:81), a shibboleth is the result of processes and practices in which words or linguistic phenomena are recognized by speakers as typical for a specific, often ‘other’, group of speakers. Even if the usage of the suffix is judged as wrong, it may still be recognized as Brabantish.

The process of enregisterment, i.e. establishing an indexical link between a particular feature and a speech style (Agha Reference Agha2003, Johnstone Reference Johnstone2016), is gaining foothold especially among younger speakers who do not speak the dialect as their first language (e.g. Doreleijers, Van Koppen & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers, van Koppen and Swanenberg2020, Doreleijers Reference Doreleijers2023). For example, these speakers produce utterances in which the masculine gender suffix -e(n) is combined with feminine or neuter nouns such as ene vrouw ‘a-m woman.f’ and ene koekske ‘a-m cookie.n’. In these magnifications, so-called hyperdialectisms, the dialect feature is overused according to the traditional dialect grammar (Lenz Reference Lenz and Gunnarsson2004, Hinskens Reference Hinskens, Braunmüller, Höder and Kühl2014). In addition, youngsters produce traditional forms such as enen hond ‘a-m dog.m’ or innovative stacked suffixes such as enenen hond (Doreleijers et al. Reference Doreleijers, van Koppen and Swanenberg2020).

The hyperdialectal usage of the masculine gender suffix appears to be an intriguing case for sociolinguistic research into linguistic variables as ‘components of styles’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:456). As for the Brabantish case, in particular the online context of social media has proven to be a genre in which hyperdialectisms are not simply manifestations of speakers overusing the feature because they do not know any better (Trudgill Reference Trudgill and Fisiak1988:551). By contrast, hyperforms are meaningful linguistic signs deployed to create a persona style (Eckert Reference Eckert2008), or an enregistered voice (Agha Reference Agha2005), that draws on the local identity of Brabant as a place and de Brabander as a person belonging to that place. This persona revolves around the question ‘what kinds of people live there and what activities, beliefs and practices make it what it is’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:462). Previous research into the Brabantish context has been partially able to capture this idea of locality by investigating stylistic practices on social media. For example, in a study of so-called ‘tiles’ with Brabantish jokes and aphorisms on Instagram, Doreleijers (Reference Doreleijers2023) found compelling evidence for a characterological figure of de Brabander being perceived as bon-vivant and convivial but at the same time as rough, burly, and sometimes even slightly sexist. Interestingly, the masculine gender suffix turns out to be one of the main features that contribute to this image, even if it is used in ungrammatical, i.e. hyperdialectal, ways. However, this does not apply to everyone, as digital comments reveal that some speakers consider the anomalous use of the suffix as erroneous and therefore non-authentic. In other words, social meanings are variable at the level of individual speakers as the particular qualities indexed by a linguistic variant may differ between speaker or listener groups, depending on the broader social context in which they appear (Walker et al. Reference Walker, García, Cortés and Campbell-Kibler2014). Moreover, the observed variation raises questions for the offline reality, in particular whether the (hyperdialectal) gender suffix is also used in speech outside the digital space.

Another issue relates to the demographic variable of age, as Brabantish hyperdialect is generally seen as a symptom of dialect loss or decay caused by younger speakers who have not properly acquired the dialect grammar (e.g. Hoppenbrouwers Reference Hoppenbrouwers1990:124). Therefore, it is often assumed that older people show stronger rejections when they encounter hyperdialectisms (non-conforming dialect) than younger people. To investigate this supposed difference, an acceptability judgment task with 25 younger and 25 older participants (see Section 3.1) was conducted prior to the qualitative focus group study (Doreleijers & Grondelaers, Reference Doreleijers and Grondelaersforthcoming). The acceptability ratings from this study (with spoken hyperdialectisms presented via audio fragments) confirm that older participants (mostly L1 speakers who acquired the dialect as their first and home language) are indeed more likely to reject hyperdialectisms than younger participants (mostly L2 speakers who acquired (leveled) dialect as a second language later in life). However, the reasons why they choose to reject or accept a hyperdialectism do not emerge in such a quantitative study, as qualitative statements from the focus group discussions were necessary to make claims about the motives for and constraints on grammatical variation (see also Jamieson Reference Jamieson2020). The aim of the present paper is thus to further map younger and older speakers’ reactions towards non-conforming dialect, i.e. hyperdialectisms, based on the focus groups. In particular, this qualitative study searches for the social meaning(s) participants assign to the Brabantish gender suffix. What kinds of social meanings can the gender suffix have, and how does it become part of a Brabantish speech style?

This paper is structured as follows. First, Section 2.1 elaborates on the changing function of the Brabantish gender suffix. Then, Section 2.2 takes a closer look at the concepts of indexicality and the indexical field (Eckert Reference Eckert2008). Subsequently, Section 2.3 provides information on the research context of North Brabant, especially on normativity in the dialect. Section 3 describes the qualitative method for the current study with different subsections on the participants, procedure, and data analysis. Building on the different themes identified within the data, Section 4 presents the main results including the most revealing participant quotes. In Section 5, the social meanings found in these data are mapped on an indexical field and discussed to answer the above-mentioned research question.

2. Sociolinguistic framework

2.1 The changing function of the gender suffix

The grammatical function of the Brabantish gender suffix has evolved over the centuries, similar to processes of change in other Germanic languages; see Bandle et al. (Reference Bandle, Kurt Braunmüller, Allan Karker, Telemann, Elmevik and Widmark2002), and more specifically Van Epps et al. (Reference Van Epps, Carling and Shapir2021) on gender change in North Scandinavian languages. Originally, it was not only present in the dialects of North Brabant (Van Ginneken Reference Van Ginneken1934). In Middle Dutch, until the seventeenth century, the suffix was a marker for the accusative case of masculine words (Doreleijers & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers and Swanenberg2023b). When Dutch emerged as a national language during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the adnominal gender system no longer distinguished between three genders. Instead, a switch to a two-gender system occurred that only distinguished between common and neuter gender (Bloemhoff & Streekstra Reference Bloemhoff and Streekstra2013:201). During that time, the suffix developed into a masculine gender marker for all cases except the genitive, but the suffix quickly disappeared in Dutch (Bloemhoff & Streekstra Reference Bloemhoff and Streekstra2013:203). Interestingly, this was not the case for the North Brabantish dialects, where it became a masculine gender marker for all grammatical cases. Today, the suffix is still intact in the local Brabantish dialects.

However, the tide can turn, as the number of Brabantish dialect speakers is declining sharply (Hoppenbrouwers Reference Hoppenbrouwers1990, Swanenberg & Van Hout Reference Swanenberg, van Hout, Hinskens and Taeldeman2013, Versloot Reference Versloot2020). In particular, children no longer acquire it as a first language in favor of Standard Dutch, often with a Brabantish accent and other regional features. Also, increased mobility and urbanization have led to increased language contact resulting in dialect leveling. Therefore, the current dialect is best described as an intermediate variant with lexical, phonological, and (morpho)syntactic features both from the standard language and the local dialect(s) (Hoppenbrouwers Reference Hoppenbrouwers1990. Britain Reference Britain2009). The gender suffix is one of the features still part of this Brabantish repertoire (e.g. Doreleijers Reference Doreleijers2023, Doreleijers & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers and Swanenberg2023a). Therefore, not only do the older L1 speakers make use of the suffix, but also younger speakers who have not fully acquired the dialect grammar but still attempt to sound local. As a result, the suffix is used in hyperdialectal ways, e.g. ene vrouw ‘a-m woman.f’ instead of en vrouw, as described in Section 1. This hyperdialectal usage of the masculine gender suffix obviously calls into question the meaning of the suffix. If the suffix is also used with neuter or feminine nouns, its original grammatical function of marking masculine gender is fading away. At the same time, older dialect speakers may still adhere to the original grammatical function.

Therefore, we assume that different functions or meanings of the suffix can co-exist and co-occur between and within speakers. As shown in a previous study of Doreleijers et al. (Reference Doreleijers, van Koppen and Swanenberg2020), younger Brabantish speakers show different linguistic behavior regarding the gender suffix, because they do not share the same grammatical knowledge (either with each other or with older speakers) (Dąbrowska Reference Dąbrowska2012, Reference Dąbrowska2020). However, the diverse social practices speakers are engaged in may be another reason for inter-individual and intra-individual variation in the use of the suffix, implying differences in the (social) meanings assigned to it as well:

Since the same variable will be used to make ideological moves by different people, in different situations, and to different purposes, its meaning in practice will not be uniform across the population (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:467; see also Johnstone & Kiesling Reference Johnstone and Kiesling2008).

Across different languages, this ‘malleability of social meaning’ (Maegaard & Pharao Reference Maegaard, Pharao, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021:203) has been researched and demonstrated in several discourse-analytic and experimental (matched-guise) studies (e.g. Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2008, Moore & Podesva Reference Moore and Podesva2009, Levon Reference Levon2014, Pharao et al. Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Spindler Møller and Kristiansen2014, Walker et al. Reference Walker, García, Cortés and Campbell-Kibler2014, Podesva et al. Reference Podesva, Reynolds, Callier and Baptiste2015, Maegaard & Pharao Reference Maegaard, Pharao, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021). However, a fine-grained analysis of the potential meanings of the Brabantish gender suffix is not yet available despite its ‘unstable’ grammatical condition. Interestingly, for Norwegian varieties, it has already been advocated that variation in gender marking may be deliberate and socially indexical, and that the interactional context at the micro-level should be taken into consideration while studying the relationship between identity and the social meaning of grammatical gender (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2021).

2.2 Indexicality of the gender suffix

Before proceeding with the present study, we take a closer look at the concepts of indexicality and the indexical field, which are essential in exploring the social meaning(s) of linguistic variation. The concept of indexicality – the idea that ‘forms of communication are indexically linked with social value, i.e. due to ideologies of communication’ (Spitzmüller Reference Spitzmüller2015:129) – originates in linguistic anthropology. It takes the social meaning of variation as its point of departure, instead of structural change (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003, Eckert Reference Eckert2008). Indexicality is a key concept within Third-Wave Sociolinguistics, in which social meaning is seen as a ‘design feature’ of language (Eckert Reference Eckert and Coupland2016:68). Although there is a large amount of large-scale variation research investigating the correlations between linguistic variables and abstract demographic categories, such as gender, class, or ethnicity, this approach does not entail how meanings become associated with these variables or social categories in social practice (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:454). Regarding this question, Silverstein (Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985) argued that the indexical link between variables and social categories is not direct, but rather indirect, as categories are associated with qualities and stances to which people relate. For example, younger speakers deploying linguistic features from the Brabantish repertoire, such as the gender suffix, are not necessarily claiming to be a Brabander but they are making claims about what a Brabander is. It is a way of ‘asserting one’s local authority and/or locality’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:464). Adopting the gender suffix allows participants to affiliate with one or more positive qualities of the Brabander, without claiming to be an eloquent Brabantish speaker or a Brabander at all.

The indexical value of a linguistic feature is assumed not to be precise and fixed, but fluid and open for reinterpretation (Eckert Reference Eckert2008). For example, once a speaker has attributed a social meaning to the gender suffix, such as conviviality, the feature becomes a resource for other speakers as well. They can incorporate the feature into their own style (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:457), hence changing the range of potential meanings, e.g. from conviviality to ‘X’ or ‘Y’. Methodologically, this range can be mapped onto a so-called indexical field: ‘a constellation of ideologically related meanings, any one of which can be activated in the situated use of the variable’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:454, 464). Within this field, speakers are operating as stylistic agents by making ideological moves, or, in other words, by making side steps in the field equivalent to what Silverstein (Reference Silverstein2003) calls indexical orders (1st, 2nd, 3rd). As for the Brabantish gender suffix, indexicality is assumed to exceed the first order (i.e. outsiders observing that the feature is used by Brabantish speakers), since previous research of Doreleijers (Reference Doreleijers2023) reveals a certain amount of awareness of the users themselves about the suffix’s indexicality (second order). Moreover, the use of the suffix turns out to be considered ‘typically’ Brabantish (third order), at least in the context of social media. The current study should clarify whether the suffix is also recognized as indexical in the offline setting of the focus groups, and which of the meanings in the indexical field will be associated with it.

Importantly, the suffix seems to act as a variable that only gains meaning in co-occurrence with other linguistic forms as well as other stylistic systems, i.e. non-linguistic semiotic signs, activities, beliefs, and practices associated with Brabantish culture (Cornips & De Rooij Reference Cornips, De Rooij, Smith, Veenstra and Aboh2020, Doreleijers & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers and Swanenberg2023a). A languagecultural approach (cf. Agar’s (Reference Agar1994) ‘languaculture’) emphasizes the interconnectedness of language and culture, and seeks to study all important clues to unravel a linguistic style. Speakers who use the gender suffix may, for example, also use other dialect features such as t-deletion (e.g. wa instead of wat ‘what’), lexical shibboleths such as the farewell greeting houdoe ‘bye’, or the personal pronoun gij instead of jij ‘you’ (Swanenberg Reference Swanenberg2014b). Also, they may listen to typical Brabantish music artists, consume typical Brabantish food and drinks, visit local football clubs, celebrate the annual carnival festival, etc. The established connection between different style systems, i.e. between the linguistic practices and social practices (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000), is also called a persona style (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:456). In turn, persona styles emerge from a process of bricolage (Hebdige Reference Hebdige1979), ‘in which individual resources (in this case variables) can be interpreted and combined with other resources to construct a more complex meaningful entity’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:456-457). Therefore, one might wonder whether it is methodologically possible to isolate the gender suffix from other features relevant to the style in question.

In any case, the (re-)indexicalization of a linguistic variable inevitably turns existing language norms upside down. For example, if the gender suffix loses grammatical function for some speakers, for others this may result in ungrammatical utterances. Section 2.3 deals with some of the key aspects of normativity in the Brabantish dialects.

2.3 Normativity in the Brabantish dialects

A particular linguistic variant, in this case the hyperdialectal gender suffix, only gains meaning by having a benchmark from which speakers can deviate, that is, it can only be perceived as hyperdialectal because the dialectal variant exists as well (Lenz Reference Lenz and Gunnarsson2004, Doreleijers & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers and Swanenberg2023b). This benchmark, or the language norm, is created moment to moment by the speakers themselves, as the Brabantish dialects are not officially recognized, standardized, and taught in schools (Swanenberg Reference Swanenberg2014a, Doreleijers Reference Doreleijers2022).Footnote 3 In other words, Brabantish is not a uniform variety but rather a set of local varieties showing similarities but also differences. Moreover, it lacks prescriptive norms, i.e. norms that prescribe how the language is used ‘in the “right” way’ (Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999:1). This raises the question of how speakers know ‘right’ from ‘wrong’, especially since dialect speakers are generally assumed to care deeply about the correctness and purity of their dialect (e.g. Verhoeven Reference Verhoeven1994). From the second half of the twentieth century, linguists have diligently tried to capture the traditional dialect grammar in reference works (e.g. De Bont Reference De Bont1962, Weijnen Reference Weijnen1971). However, these descriptive grammars consist of detailed expositions of specific local dialect features and are mainly aimed at documentation; they are not primarily meant to be resources providing instructions about how to use the dialect in a proper way.

Therefore, Brabantish language norms (e.g. regarding the gender suffix) should rather be treated as resulting from linguistic practices within the language community as well as the associated evaluative behavior of these practices (see Bartsch Reference Bartsch1987). Speakers of the same language share a set of norms, that is, ‘the speech community is not defined by any marked agreement in the use of language elements, so much as by participation in a set of shared norms’ (Labov Reference Labov1972:120–121). Traditionally, grammatical knowledge mainly stems from tradition, i.e. speakers receiving extensive input while growing up, thereby (unconsciously) adopting the locally defined norms (Hoppenbrouwers Reference Hoppenbrouwers1990). When proficient speakers are faced with dialect they perceive as ‘outside the norm’, they generally represent a form of conservatism. They cling to their ‘favored forms or styles of earlier times’ (Dorian Reference Dorian1994:480), although their norms are not those shared by the community as a whole, especially not by the younger speakers who exhibit a different kind of grammatical knowledge (of an altered dialect).

The next section describes the method of the current study in which we aim to map speakers’ reactions to non-conforming dialect to uncover underlying language norms and social meanings. To increase feasibility in the highly diverse Brabantish landscape, we have narrowed the research focus to the dialect spoken in the city of Eindhoven (and surrounding villages). With more than 260,000 inhabitants, Eindhoven is the largest city in the province of North Brabant. Moreover, it has been drastically affected by urbanization and modernization in recent decades, mainly due to its booming high-tech industry. These social changes have also influenced the dialect spoken in Eindhoven, showing both symptoms of leveling (Hoppenbrouwers Reference Hoppenbrouwers1990) and innovation in younger generations (Doreleijers et al. Reference Doreleijers, van Koppen and Swanenberg2020).

3. Method

3.1 Participants

A total of 25 younger participants (aged 16–18; M: 16.6) and 25 older participants (aged 50+; M: 72.5) took part in this study. They were divided into ten group sessions with five participants in each group (see Matthews & Ross Reference Matthews and Ross2010:235, Krueger & Casey Reference Krueger and Anne Casey2015:81–82). All groups consisted of younger or older participants; there were no mixed age groups. The younger participants were recruited through a school for secondary education (senior general and pre-university level) in the city center of Eindhoven. The teachers recommended which students could participate (but their participation was voluntary), based on their dialect background (although they did not have to be raised exclusively with the dialect), their place of birth and residence (i.e. the city of Eindhoven or a village nearby), and their membership of a peer group of close friends that could participate together in the focus group interview. Also, the younger participants were required to have a clearly recognizable Brabantish way of speaking in terms of accent, lexicon, and grammar.

The older participants were recruited through the network of the provincial heritage organization Erfgoed Brabant and came from five different villages near the city of Eindhoven. First, five L1 dialect speakers were approached by the researchers (by email) to participate in the study. Each of them then contacted four relatives or friends to join them in the focus group interview.

Two researchers (the authors of this paper) who are both familiar with the Brabantish dialect, one as an L1 speaker and one as an L2 speaker from Eindhoven, visited all participants to conduct the interviews. The focus group interviews with the younger participants took place in a classroom at the secondary school during regular school hours (after the students’ last class). Participating students were allowed to skip a Dutch language and literature class the week after the study to compensate for their invested time. The interviews with the older participants were conducted in different places (i.e. the home of one of the participants or at local history or dialect centers), as the location was chosen by the participants themselves. All participants received a letter one week prior to the study, containing information about the general topic and the procedure of the study. At the beginning of each session, informed consent was provided by the participants.Footnote 4

3.2 Procedure

The focus group study lasted 60 minutes in total and consisted of three parts. In the first part, participants provided demographic data on their age, gender, place of birth, and residence, and linguistic profile. Also they were given statements on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘totally disagree’) to 5 (‘fully agree’) to gauge their overt dialect attitudes. Two of these statements were discussed later during the focus groups interviews:

-

I sometimes comment on the Brabantish language use of others.

-

I sometimes get annoyed by the Brabantish language use of others.

In the second part of the study, which took approximately 20 minutes, participants carried out an acceptability judgment task comprising 76 spoken sentences (audio fragments) with and without hyperdialectisms. This rating study will not be discussed in detail in the present paper, as the main focus is on the qualitative material (see Doreleijers & Grondelaers, Reference Doreleijers and Grondelaersforthcoming).

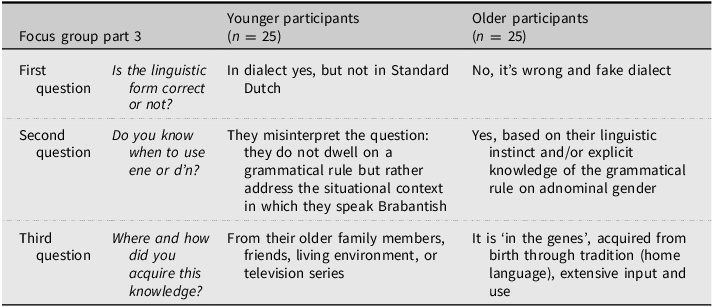

In the third part of the study, participants took part in focus group interviews, each of which lasted 31 minutes on average. The lingua franca of all interviews was Dutch, but occasional interference of the Brabantish dialect was allowed. In the focus groups, participants were presented with three different prompts in a row containing pictures with Brabantish texts. Each prompt included one or more gender suffixes, one of which was used in a hyperdialectal way (see Figures 1–3). The first picture was taken at the entrance of a restaurant called d’n Boerderij ‘the-m farm.f’ in the North Brabantish capital city of ’s-Hertogenbosch. This restaurant name is hyperdialectal, as it comprises a feminine noun boerderij ‘farm’ preceded by a masculine gender suffix on the definite article d’n ‘the-m’. Note that the other linguistic elements in the picture are written in Standard Dutch, i.e. restaurant en zalen voor uw feest, lunch of diner ‘restaurant and rooms for your party, lunch or dinner’ and puur en bourgondisch ‘pure and burgundian’. In this case, ‘burgundian’ has a figurative meaning, referring to an exuberant life style. The second picture comes from the Instagram page of Omroep Brabant, the main (regional) news broadcaster of the province. It contains a Brabantish joke (was munne buuk maor net zo plat als munne dialect ‘if only my belly was as flat as my dialect’)Footnote 5 , featuring a hyperdialectism munne dialect ‘my-m dialect.n’, i.e. a neuter noun dialect ‘dialect’ preceded by a masculine gender suffix on the possessive pronoun munne ‘my-m’. The third picture was taken from the popular Instagram page of RoekOe Brabant that produces funny Brabantish jokes or texts on black ‘tiles’ (Doreleijers Reference Doreleijers2023). This picture contains a hyperdialectism in which an animate feminine noun dame ‘lady.f’ is preceded by a masculine gender suffix on the indefinite article unne ‘a-m’. The text consists of a dialogue between the female person Truuske and an undefined male person, asking Truuske about her age (Hoe oud bende gij? ‘How old are you?’). Truuske replies in an offended manner: Zoiets vraogde nie aon unne dame! ‘You don’t ask a lady something like that!’ The male person then asks for her e-mail address, to which Truuske replies with Truuske1957@gmail.com, thereby giving away her age.

Figure 1. Prompt 1 with hyperdialectal d’n Boerderij ‘the-m farm.f’.

Figure 2. Prompt 2 with hyperdialectal munne dialect ‘my-m dialect.n’.

Figure 3. Prompt 3 with hyperdialectal unne dame ‘a-m lady.f’.

Note that the first two prompts (Figures 1 and 2) also include non-linguistic features that could index Brabantishness, such as the use of the colors (red and white) and patterns (checkered, so-called Brabants bont) of the Brabantish flag. In contrast to the first prompt, the second and third prompt (Figures 2 and 3) contain other linguistic features than the gender suffix that are typical to the Brabantish dialect, such as the non-standard spelling of maor ‘if only’ and aon ‘to’ (instead of maar and aan), the (inverted) verb forms bende ‘are you’ and vraogde ‘ask you’ (instead of ben je and vraag je), the personal pronoun gij ‘you’ (instead of jij), t-deletion in wa ‘what’ and nie ‘not’ (instead of wat and niet), and the possessive pronoun oew ‘your’ (instead of jouw).

The participants had to respond to the prompts individually and all together by means of a group discussion. In each group, the researchers started the conversation by asking the same question, i.e. ‘Is this picture Brabantish to you?’ Then, the participants could take the lead to start talking, and because the groups consisted of peers, a natural flow in the conversations quickly developed. Meanwhile, the researchers kept an eye on ensuring that each participant had sufficient opportunity to speak, and, if necessary, asked a question directed at a specific individual to include them in the discussion. Also, the researchers joined the discussion by asking specific questions as a guidance or to clarify at some point. To keep the main topics across the different focus group sessions as consistent as possible (i.e. to ensure they were discussed in a similar fashion and in the same order), the researchers used a topic guide (see Matthews & Ross Reference Matthews and Ross2010:246). This topic guide is included in Appendix A. In the first part of the interview, the participants had to discuss the three prompts on the basis of the already mentioned general question and two follow-up questions:

-

Is this picture Brabantish to you?

-

If yes, which linguistic features contribute to Brabantishness? (Or if not, why not?)

-

How authentic does this language come across?

In the second part of the interview, the researchers raised two statements from the questionnaire. Participants where asked if and how they are (sometimes) commenting on the Brabantish language use of others and why. Also, they were asked if they are (sometimes) annoyed by the Brabantish language use of others.

Finally, in the third part of the interview, the researchers reintroduced the prompts to specifically ask the participants about the use of the gender suffix in the pictures. At this point, the gender suffix was mentioned for the first time in the study to ensure that earlier participants’ reactions were not influenced by their awareness of the feature. In general, this part was guided by three questions:

-

Do you consider these forms correct or wrong?

-

Do you know when to use ene or den in Brabantish?

-

Where and how did you acquire this knowledge?

3.3 Data analysis

The interviews were recorded (using a camcorder) and transcribed afterwards by two researchers.Footnote 6 The transcribed data were analyzed manually by means of a thematic analysis, ‘a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within the data’ (Braun & Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006:79), particularly focusing on the (social) meanings ascribed to the (anomalous) use of the gender suffix. The main focus of the analysis was on thematic content, mostly leaving aside the specific linguistic forms that were used by the participants, as the lingua franca of the focus group discussions was Dutch and the study centered around metalinguistic awareness rather than linguistic form. In the analysis of the ten focus groups, we identified twenty different themes, which can be accessed through the code book in Appendix B. The selection of the relevant participant quotes in Section 4 is based on their ‘keyness’ (see Braun & Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Please note that this selection criterion is ‘not necessarily dependent on quantifiable measures – but rather on whether it captures something important in relation to the overall research question’ (Braun & Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006:82).

4. Results

4.1 Participants’ reactions to the hyperdialectal prompts

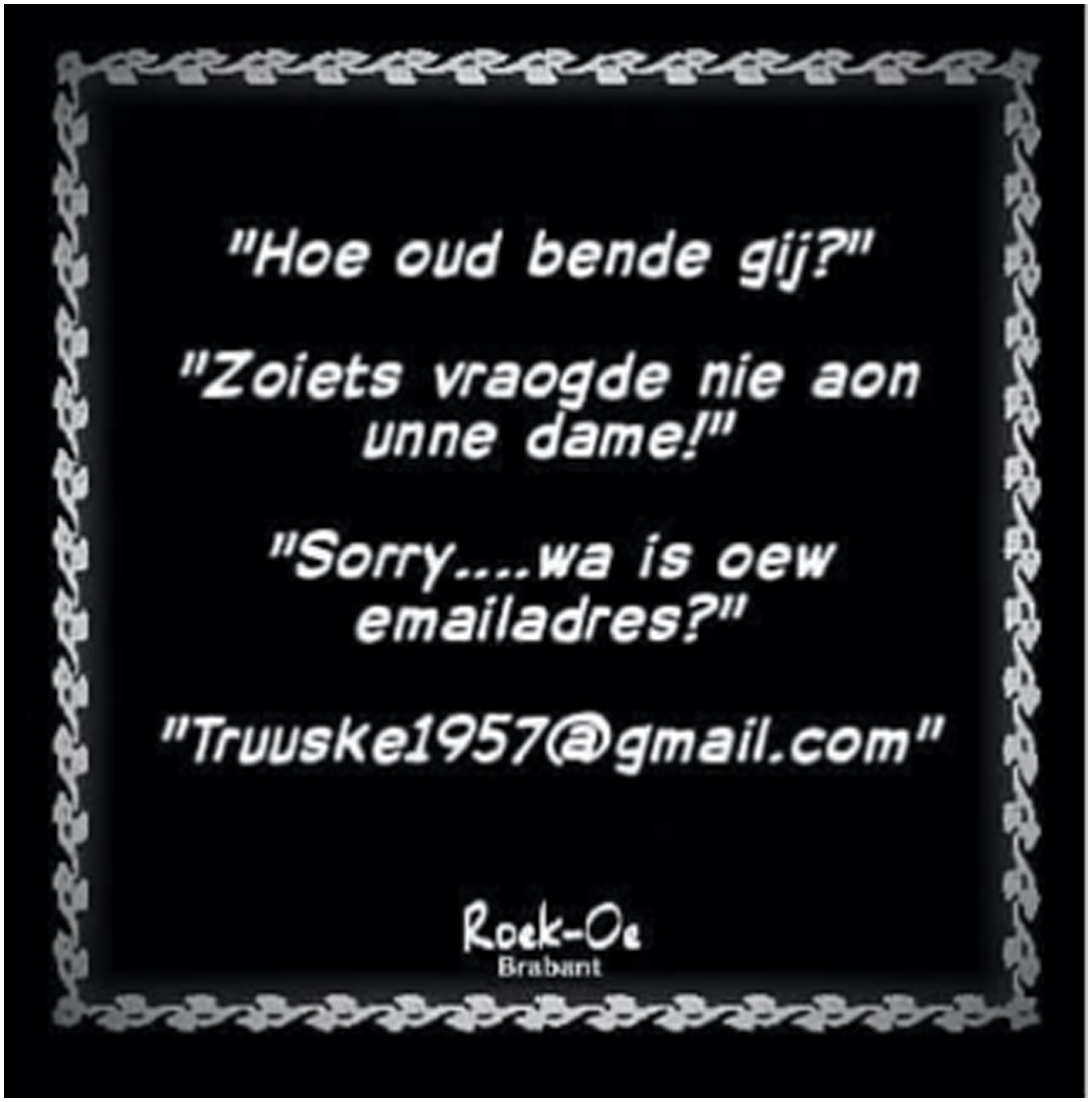

In the first part of the focus groups, participants were asked to respond to the three prompts described in Section 3.2 (see Figures 1–3). The general results for the younger and older participants are displayed in Table 1. Strikingly, there is a strong contrast between the younger and older participants when it comes to the Brabantishness and authenticity of all three prompts. Whereas the younger participants evaluated each of them as Brabantish and authentic, this was not the case for the older participants. However, there are slight differences between the three prompts, which will be discussed below.

Table 1. General results of the first part of the focus group interview

4.1.1 Prompt 1

The contrast between the younger and older participants is clearly illustrated in examples (1) and (2).Footnote 7 The quotes in example (1) show that the younger speakers consider the (hyperdialectal) use of the gender suffix in d’n Boerderij ‘the-m farm.f’ as typical Brabantish. This is reinforced by other features that the participants link to Brabant, i.e. the adjective bourgondisch ‘burgundian’ and the colors (white and red) of the Brabantish flag. All younger participants consider Prompt 1 to be Brabantish, however, some of them only partially: the use of the gender suffix indicates Brabantishness but the interference of Standard Dutch (in the remaining text on the advertising board) has a weakening effect.

For the older participants, the use of the masculine gender suffix also stands out immediately, but in a negative way. The quotes in example (2) reveal that they evaluate the use of the suffix as wrong (it is not correct Brabantish, but still recognizable as an attempt to be Brabantish). As a consequence, they perceive the picture as inauthentic.

The older participants also notice the other semiotic elements in the prompt, such as the colors and the adjectives puur and bourgondisch ‘pure and burgundian’, but they ascribe it to the attempt to convey a local image that centers around conviviality and hospitality. They think that the hyperdialectal use of the gender suffix is also part of this effort. However, this single ‘error’ takes out all credibility; see example (3).

4.1.2 Prompt 2

Prompt 2 is also undoubtedly evaluated as Brabantish by the younger participants, as illustrated by the quotes in example (4). Again, the co-occurrence of linguistic features and other-semiotic resources, i.e. the colors and the checkered pattern of the Brabantish flag, reinforces the indexical link. However, the quotes in example (5) show that some of the participants evaluate the language use in the picture as exaggerated. They would never seriously say or write this themselves, as they are more likely to expect it in the context of a joke (for fun) or when someone is drunk.

For all older participants, Prompt 2 is immediately dismissed because of the hyperdialectal gender suffix. In example (6), participant O5B directly resorts to the dialect grammar: a neuter noun, i.e. dialect (n) ‘dialect’, cannot be combined with a masculine gender suffix, just like the feminine noun, boerderij (f) ‘farm’ in Prompt 1 (see Section 4.3). The other participants agree: it makes no sense at all.

4.1.3 Prompt 3

While the older participants disapprove of the first two prompts very strongly, they are slightly less strict about Prompt 3, which they all consider to be partially Brabantish. This is due to the fact that apart from the hyperdialectal usage of the gender suffix (unne dame ‘a-m lady.f’), which is immediately corrected (’n daome ‘a-f lady.f’), the language use in the picture is perceived as ‘fitting’ the context and ‘nice’, as illustrated by the quotes in example (7).

In contrast, the younger participants do not react to the anomalous use of the suffix (again). They generally evaluate the language use in Prompt 3 as recognizable. In the quotes in example (8), they also attribute it to funny or ironic contexts in which they portray themselves as Brabantish speakers, again pointing to the stylistic function of Brabantish features including the gender suffix.

4.2 Participants’ annoyance with non-conforming dialect

The examples in Section 4.1 have already shown that the older participants can be quite annoyed by violations of the gender marking constraint. Ideally, they would self-correct the hyperdialectal use of the gender suffix, as illustrated in example (9). Here, they comment again on the masculine gender suffix preceding the feminine noun d’n Boerderij (the-m farm.f) in Prompt 1.

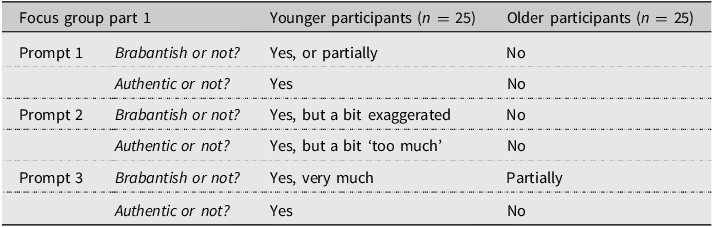

The younger participants do not feel the urge to comment on the Brabantish language use of others because they think it is wrong. The only way of commenting on another speaker is by imitating or repeating them, but only for fun, e.g. meer als een soort grapje ‘more as a kind of joke’ (Y1D) or om mensen te kutten ‘to fool people’ (Y4E). The contrast between the younger and older participants is indicated in Table 2.

Table 2. General results of the second part of the focus group interview

Because the younger participants do not feel that one can make grammatical mistakes in Brabantish, they do not get annoyed by hyperdialectisms at all. However, they do think it is annoying when someone who is not a Brabantish speaker tries too hard to speak Brabantish. For example, the participants talk about meeting people from the north of the Netherlands. The quotes in example (10) show that the annoyance has something to do with perceiving the dialect used by outsiders as forced or unnatural, for example when these outsiders are trying to imitate a Brabander.

The younger and older speakers agree on this kind of appropriation from speakers who are not from Brabant. Generally, these speakers are often called Bovensloters, lit. ‘people from above the ditch’, i.e. people from above the rivers Rijn/Waal and Maas who speak distinct dialects. When they are trying to imitate the Brabantish dialect, this can even feel like an insult, as shown in example (11).

Interestingly, the older participants also consider the language use of current younger Brabantish speakers as ‘forced’. Hyperdialectisms are symptomatic of Bovensloters, but also of younger speakers who speak (what participant O5B calls) an ‘artilect’, i.e. an artificial or makeshift dialect. In example (12), participant O1E indicates that speaking dialect is not a matter of ‘turning a switch’. This illustrates the contrast between the younger and older participants: the younger ones make use of the dialect more occasionally, as an ‘accessory’ depending on the situational context, whereas it is often a base language for the older speakers (see Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos, Auer and Erich Schmidt2010:746–747).

However, the older participants are also aware that the current dialect is changing into what they call ‘geciviliseerd dialect’ (‘civilized dialect’), a modern dialect that evolved from increased mobility and influence from Standard Dutch. At this point, not all speakers agree on whether this kind of language change is desirable or not. Some participants are skeptical, while others, such as participant O1B, think that mixing elements from Brabantish with other languages is beautiful: Ik vin eigenlijk: as ze ’t Brabants gebruiken en Brabants praoten, eh, die mix, da vind ik – ja, da vin ik – vin ik mooi! ‘Actually, I think that if they use and talk Brabantish, this mix is beautiful!’

The younger participants also try to balance between the old dialect and the modern dialect, and both have different associations, as illustrated by example (13).

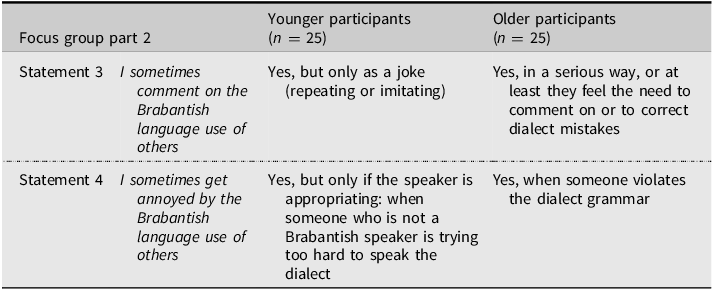

4.3 Participants’ awareness of a grammatical norm

Also when it comes to the awareness of a grammatical norm, the younger and older participants are each other’s extremes. In the third part of the focus group interviews, their attention was explicitly drawn to the hyperdialectal gender suffixes in the prompts, and they were asked about the correctness of these forms. The general results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. General results of the third part of the focus group interview

For the older participants, it is very clear that all hyperdialectisms indicate wrong and fake dialect, i.e. dan heb ik meteen zo’n nepgevoel ‘then I immediately have this feeling that it’s fake’ (participant O5B). The younger participants do not normatively reflect on the hyperdialectisms at all. They consider them to be ‘normal’ Brabantish, but of course incorrect Standard Dutch, as they take the standard language as the norm for evaluating the correctness of the Brabantish forms, without realizing there could also be a (grammatical) dialect norm: Ik weet dat het geen goed Nederlands is, maar je weet het is Brabants dus het is zo geschreven ‘I know it’s not correct Dutch, but you know it’s Brabantish so it’s written that way’ (participant Y5D).

This difference in awareness is also reflected in the participants’ knowledge of a grammatical rule underlying the use of the adnominal gender suffix. It turns out that the older participants possess quite some explicit knowledge about this grammatical rule, while the younger ones completely lack this knowledge. However, the older participants differ in the extent to which they can articulate the rule. Some follow their linguistic instinct without being able to reproduce the grammatical rule, whereas others know that the suffix is connected to masculine gender, as shown in example (6). The younger participants adapt the use of the suffix to the situational context or to the stylistic practice, that is, they use it as an identity marker when they want to emphasize that they come from Brabant; see examples (14) and (15) (see Doreleijers, Mourigh & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers, Mourigh and Swanenberg2023).

The younger and older participants also differ in terms of acquisition. The younger participants indicate that they picked up the dialect in their living environment through contact with older family members and friends, and by watching popular movies or television series, but not so much as an everyday home language. In addition, they believe that the genuine dialect can only be acquired through immersion in rural areas and villages, not in a city like Eindhoven, as revealed in example (16).

The older participants report that they have acquired the dialect since birth, because they always spoke dialect, i.e. plat, at home or at the spulplòts ‘the playground’, and therefore it is ‘in their genes’; see example (17).

5. Discussion

The quotes in Section 4 not only reveal large differences between the younger and older participants in their reactions to non-conforming dialect, i.e. the hyperdialectisms, but also between the potential social meanings that can be ascribed to the linguistic variable, in this case the masculine gender suffix. Previous research (e.g. Doreleijers et al. Reference Doreleijers, van Koppen and Swanenberg2020, Doreleijers Reference Doreleijers2023, Doreleijers & Swanenberg Reference Doreleijers and Swanenberg2023b) already indicated that the suffix is drifting away from its original grammatical function. This change is supported by the qualitative statements from the younger participants in the current study. They do not think about the suffix in terms of grammaticality (knowing ‘right’ from ‘wrong’), but rather in terms of appropriateness within the context of use. The use of the gender suffix, whether in the ‘traditional’ way (i.e. in line with the grammatical constraints) or in a hyperdialectal way, helps to convey a Brabantish image. However, the gender suffix is part of a larger range of semiotic elements indexing ‘Brabantishness’, both linguistically and non-linguistically. For example, Brabantishness can also be achieved through the use of other dialect features that are recognized as Brabantish by the younger participants (second-order indexicality), such as the use the personal pronoun gij ‘you’.

In addition, the younger participants mentioned the use of the Brabantish colors (white and red) and the Brabantish flag as indexically linked to Brabant(ishness). Also, references to the convivial and burgundian character of the province contribute to the overall Brabantish image. Note that these semiotic elements were only brought up by the participants because they were present in the prompts. Perhaps other prompts could also evoke other meaningful elements. From a languagecultural perspective (Agar Reference Agar1994, Cornips & De Rooij Reference Cornips, De Rooij, Smith, Veenstra and Aboh2020), however, we can already conclude that the co-occurrence of semiotic resources reinforces the indexical link between the gender suffix and Brabantishness, or, in other words, the suffix is in itself already associated with Brabant, but the association is strengthened by the presence of other indexical links.

Interestingly, these indexical links are also noted by the older participants in the focus groups, but the use of non-conforming dialect has a detrimental effect. As soon as an older participant notices a hyperdialectism, in this case a masculine gender suffix combined with a feminine or neuter noun, the overall credibility is completely lost. This is related to the fact that, for them, the suffix is still subject to grammatical constraints. These differences in grammatical knowledge between the younger and older participants are reflected in their sense of a norm, with the older participants still relying on masculine lexical gender and the younger participants accepting the use of the suffix in any context, unless it is appropriated by an outsider, i.e. someone who is not part of the community who is trying to talk (and behave) like a Brabander.

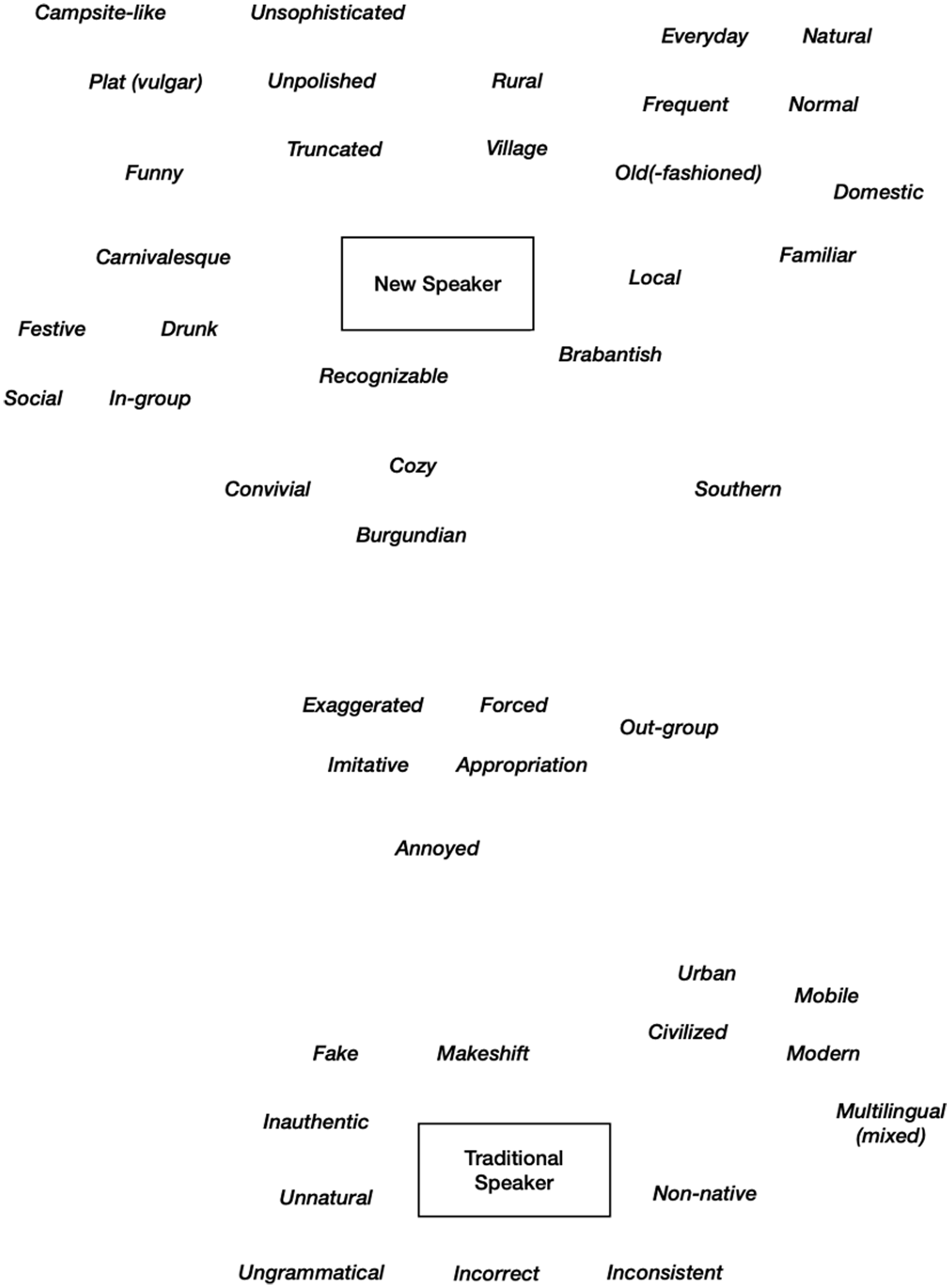

Besides, the participants’ reactions to non-conforming dialect reveal deeper ideologies about the dialect, which is for example reflected in the adjectives they used during the focus group discussions. Both younger and older speakers are aware of changes in the local dialect due to urbanization, increased mobility, and language shift, especially in the highly diverse linguistic landscape of cities like Eindhoven. Moreover, the growing importance of languages with more overt prestige, such as Standard Dutch and English, contributes to practices of languaging (Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Sif Karrebæk, Malai Madsen, Spindler Møller, Arnout, Blommaert, Rampton and Spotti2015) in which the dialect is mixed with other varieties in plurilingual linguistic expressions. The older participants evaluate the dialect use of younger speakers, i.e. speakers of the ‘new’ dialect (Swanenberg Reference Swanenberg2014b), as modern and civilized, but also as artificial (e.g. fake, makeshift, and inauthentic), whereas the younger speakers still link ‘their’ dialect to localness and consider it to be ‘recognizable’ Brabantish.

Strikingly, for the younger participants, the (potential) social meanings related to the variable in question can still be very diverse. On the one hand, the suffix’s presence in the language is seen as normal and frequent (it is just there), especially in rural, village, or domestic (e.g. at the grandparents’) contexts where it can also evoke feelings of old-fashionedness. On the other hand, however, the suffix is linked to adjectives such as unsophisticated, unpolished, and plat, as it is more likely to be encountered on the campsite than in a luxury five-star hotel. Nevertheless, it also plays a role in in-group peer contexts where dialect use is funny (related to its somewhat blunt connotation), especially in non-serious settings during carnival festivities or when going out with friends, often involving alcoholic drinks. The use of the gender suffix can then contribute to creating a convivial atmosphere, which is also linked to the overall character of the province.

The strong indexical link between the gender suffix and Brabantishness, not only as a way of speaking but also as a way of being (i.e. third-order indexicality), makes the feature ideally suitable for stylistic practices in which local identity is ‘enacted’ by the speakers. This can be done not only by Brabantish community members (in-group) but also by people from outside the community (out-group), for example people from the north(west) of the Netherlands, who try to imitate the southern dialect. This often leads to evaluations of the (hyper)dialect as ‘exaggerated’ and ‘forced’ by both younger and older participants. At this cutting edge of (un)belonging (see Cornips & De Rooij Reference Cornips and De Rooij2018), younger and older speakers are most likely to share the same social meanings.

In Figure 4, an indexical field (see Eckert Reference Eckert2008) is presented based on the results of the focus group interviews. The speaker types in the boxes indicate the two participant groups, namely the younger ‘new’ speakers (who acquired the (leveled) dialect as a second language later in life and who use dialect features in innovative ways) and the older ‘traditional’ speakers (who acquired the traditional dialect – as documented in traditional dialect descriptions such as De Bont (Reference De Bont1962) and Weijnen (Reference Weijnen1971) – as their first and home language). Within the field, the italicized adjectives surrounding the speaker types should be interpreted as social meanings related to the hyperdialectal suffix -e(n). Please be aware that the distances in the field are approximate. Moreover, Figure 4 does not include alternatives to hyperdialectal -e(n), which means that the social meanings in this field do not cover the grammatical variant of the suffix that is used with masculine nouns (e.g. ene man ‘a-m man.m’), as only hyperdialectisms were investigated in the prompts. However, we presume that an indexical field featuring the grammatical variant of the suffix would not lead to different evaluations on the part of the younger ‘new’ speakers, as the younger participants in the current study were unable to distinguish between hyperdialectisms and ‘correct’ dialect forms. In contrast, we do expect the older ‘traditional’ speakers to report opposite social meanings in an indexical field centered around the grammatical variant of the suffix. For example, we would expect adjectives such as fake, unnatural, non-native, and inauthentic to be replaced by counterparts such as genuine, natural, native, and authentic. Also, adjectives such as urban, civilized, and modern are expected to give way to adjectives such as suburban, rural, and nostalgic. Follow-up research could therefore include conventional usage of the gender suffix in the prompts as well.

Figure 4. Indexical field of hyperdialectal Brabantish gender suffix -e(n). Boxes = speaker types, italicized = meanings for the hyperdialectal variant.

The proposed indexical field in Figure 4 is by no means intended to be exhaustive. Each of the meanings in the field deserves closer investigation in future research. The aim of this paper was to give an overview of the range of (potential) social meanings that speakers attribute to the non-conforming Brabantish gender suffix, and to show how the suffix becomes part of a Brabantish speech style ‘outside the norm’. For now, we cannot identify one such style, but depending on the context, there seem to be several persona styles that can be called upon by individual speakers, such as ‘the old-fashioned, rural dialect speaker’, ‘the blunt and unsophisticated platpraoter’ (see note 5), ‘the social and funny buffoon’, ‘the familiar companion’, or ‘the convivial and burgundian Brabander’. In all of these persona styles, the hyperdialectal gender suffix can serve as one of the meaningful components, at least for the younger speakers. For the older speakers, however, a speaker must inevitably use the suffix in accordance with the traditional dialect grammar in order to be styled as an authentic local.

To further explore the underlying norms and social meanings of the gender suffix, future research calls for methods tapping into implicit attitudes and covert responses as well, for example through matched-guised experiments (see Doreleijers Reference Doreleijers2024 for a discussion). Such an experimental approach also allows for including oral prompts, since the meaning potential of the gender suffix may be enforced in written dialect. Another interesting future direction would be to organize mixed focus group interviews, in which younger and older dialect speakers could discuss prompts together. This would also counteract the somewhat artificial dichotomy between the younger participants interviewed at school, potentially leading to a degree of ‘school correctness’ in their responses, and the older participants approached at their preferred (non-institutional) locations.

In any case, the current study advocates the integration of metalinguistic comments as a ‘diagnostic tool’ (see Dorleijn & Nortier Reference Dorleijn and Nortier2019) into language variation research from a stylistic practice approach (see Quist Reference Quist2008). In times of languishing dialects, perhaps future dialectological research should also take this stylistic and metalinguistic turn.

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers and the editors of this special issue for their constructive and detailed comments on a previous version of this text. Moreover, we are grateful to all participants in this study as well as to the teachers who facilitated this research with the younger participants at school.

Appendix A: Topic guide

Introduction (approximately 5 minutes)

-

Brief thank you for participation in the two previous parts of the study (questionnaire and acceptability judgment task).

-

The aim of the focus group interview is repeated: we want to find out participants’ reactions to Brabantish language use in the Eindhoven region (NB we do not explicitly mention that this study is about hyperdialectisms in gender marking to avoid bias in the participants’ answers; the specific topic will be brought up by the researchers during the third part of the discussion).

-

Telling again that the interview will take about 30 minutes.

-

Telling again that the interview will be recorded in video and audio (as stated and agreed to in the informed consent forms that were filled out at the start of this study). Participants are again informed that none of the recordings will be publicly available afterwards and that their privacy is safeguarded in both the datasets and the publications resulting from the study.

-

Agreeing on turn-taking: everyone can take the floor, nobody interrupts each other. Depending on the situation, the researchers can ask someone to take the floor, but participants can take the floor themselves any time if they want to contribute. All participants have a fixed place in the room.

-

Room for questions from the participants.

-

The recording is tested.

-

The recording is started.

Part 1: Prompts (approximately 10 minutes)

Participants are instructed to comment on three prompts containing Brabantish language use (see Figures 1, 2, and 3). These prompts are printed out and placed on the table. They are discussed separately.

In this part of the interview, the researchers ask the participants three questions:

-

Is this picture Brabantish to you?

-

If yes, which linguistic features contribute to Brabantishness? (or if not, why not?)

-

How authentic does this language come across?

Part 2: Statements (approximately 10 minutes)

In the second part of the discussion, the researchers bring up two statements from the questionnaire to comment on (and ask related questions).

-

I sometimes comment on the Brabantish language use of others.

-

○ If yes, what kind of comments? And in what kind of situation?

-

○ Why exactly are you commenting (or why not)?

-

-

I sometimes get annoyed by the Brabantish language use of others.

-

○ Do you think you can make mistakes in Brabantish?

-

Part 3: Hyperdialectal gender marking (approximately 10 minutes)

Following the participants’ spontaneous responses in the first two parts of the interview, the researcher now specifically highlights the hyperdialectal gender suffixes in the prompts.

-

D’n boerderij ‘the farm’

-

Munne dialect ‘my dialect’

-

Unne dame ‘a lady’

Then, the following three (general) questions are asked:

-

Do you consider these forms correct or wrong?

-

Do you know when to use ene or den in Brabantish?

-

Where and how did you acquire this knowledge?

Ending (approximately 5 minutes)

-

The recording is stopped.

-

The participants are thanked for their participation in the interview and informed again on the follow-up: data will be processed pseudonymized, they will receive a notification of the results in due course via their teacher (young participants) or via Erfgoed Brabant (older participants).

-

There is room for the participants to ask further questions about the study.

-

The older participants receive a gift (a popular scientific book about dialects) as a token of appreciation. The younger participants receive a candy bar.

Appendix B: Codebook

Theme 1: The Brabantish gender suffix is explicitly noticed by the participant

Theme 2: The participant reflects on their own dialect use or perception

Theme 3: The participant recognizes dialect use from someone else

Theme 4: The Brabantish gender suffix ‘is just there’

-

normal

-

everyday

-

frequent

-

natural

-

native

Theme 5: The Brabantish gender suffix is evaluated as marked or stereotypical

-

linked to (North) Brabant

-

Brabantish

-

Brabander

-

local (see also Theme 6)

-

‘real’ Brabantish

-

recognizable

-

typical

-

authentic

-

distinctive

-

unique

Theme 6: The Brabantish gender suffix is evaluated as non-standard (pejorative)

-

plat (vulgar)

-

old-fashioned

-

unpolished or less polished

-

unsophisticated or less sophisticated

-

not standard/incorrect (see also Theme 18)

-

truncated

-

unintelligible

-

funny (to laugh at)

Theme 7: The Brabantish gender suffix is linked to other linguistic features (co-occurrence)

-

phonological

-

morphological/morphosyntactical

-

lexical

Theme 8: The Brabantish gender suffix is used in practices of stylization

-

joking/kidding

-

non-serious

-

repeating

-

imitating

-

exaggerating (in a funny way)

-

standing out

-

portraying identity

Theme 9: The Brabantish gender suffix is used in connection to popular movies or series

-

New Kids (series and movies)

-

Undercover (series)

-

Ferry (movie)

-

street language

-

camping talk

Theme 10: The Brabantish gender suffix is connected to center–periphery dynamics

-

city (of Eindhoven)

-

villages

-

rural

-

North vs. South

Theme 11: The Brabantish gender suffix is discussed in terms of urbanization

-

urban

-

civilized

-

modern

-

mobility

Theme 12: The Brabantish gender suffix is linked to leisure or festive activities

-

carnival(esque)

-

alcoholic drinks

-

going out

-

partying

-

at the bar

-

at night

-

in TikTok videos (after going out)

-

at the football club

-

music of Guus Meeuwis (concerts)

-

King’s Day

-

festivals

Theme 13: The Brabantish gender suffix is associated with familiar/domestic contexts

-

personal living environment

-

at home

-

household

-

grandparents

-

family members

Theme 14: The Brabantish gender suffix is discussed in terms of communities

-

usage of personal pronouns wij ‘us’ and ons/onze ‘our(s)’

-

among friends

-

in-group settings

-

informal settings

-

belonging

Theme 15: The Brabantish gender suffix is connected to perceived qualities of the Brabander

-

burgundian

-

convivial

-

cozy

-

hospitable

-

festive

-

speaking vernacular

Theme 16: The Brabantish gender suffix is linked to non-linguistic resources associated with Brabant

-

red and white colors

-

the Brabantish flag

-

checkered pattern (Brabants Bont)

-

font

Theme 17: The Brabantish gender suffix is discussed in terms of its grammatical function

-

lexical gender

-

phonological constraints

Theme 18: The Brabantish gender suffix is discussed in terms of normativity

-

commenting on others

-

erroneous

-

incorrect

-

ungrammatical

-

unnatural

-

inauthentic

-

forced

-

exaggerated

-

fake

-

artificial

-

makeshift

-

appropriation

-

tendency to correct

-

annoying

-

inconsequent

-

mix-up

-

non-native

Theme 19: The Brabantish gender suffix is linked to strategies in communication

-

flexible language use (register sensitivity)

-

codemixing

-

multilingualism, bilingualism

-

conversational partners/speech accommodation

Theme 20: The Brabantish gender suffix is discussed in terms of modality

-

written vs. spoken dialect