It is hard to believe, but emerging regions that have had little impact on the wine world are forcing consumers to pay attention to a completely different part of the world. A wine epicenter that includes countries like Greece, Israel and Lebanon might look familiar to someone a couple of thousand years old, but it is certainly a new part of the wine world for the rest of us.

———Squires, Wine Advocate, Reference Squires2008I found Israel like grapes in the wilderness; I saw your forefathers as the earliest fruit on the fig tree in its first season. But they … devoted themselves to shame, and they became as detestable as that which they loved.

———Hosea 9: 10 (quoted to authors by Yatir CEO Yaacov Ben-Dor)INTRODUCTION

The film Settlements Wine Operation, distributed widely in August 2010 on networks of activists and on YouTube, addressed the contested production of wine across the border between South Mount-Hebron (Palestine) and the Northern Negev (Israel).Footnote 2 Shot at night by members of Ta'ayush Hebron who were conducting field research for the economic boycott project “Who Profits from the Occupation,” the short film follows “grape smuggling from South Mount Hebron to Carmel wineries.” The film is narrated as a detective story that it says uncovers “the unbelievable plot of how the military, the police, private guards, murderous truck drivers, and a private winemaking company work together like thieves in the night to hinder documentation of the night harvest.”

How does the mundane practice of grape harvest become of such investigative interest to political activists in the West Bank? The filmmakers explain in an article: “It was brought to our attention that Carmel Winery, the largest national wine company, sources grapes from South Mount Hebron settlements. To avoid slander and to dodge the boycott of settlement products, Carmel is doing this in hiding and at night.”Footnote 3 After several dramatic twists and turns, the search came to an end with, the filmaker writes, “conclusive proof that Yatir Winery, one of Carmel wineries, purchases and processes grapes from vineyards in the settlement Susya.” This resonates with the biblical story of the expedition of Hebrew spies into Canaan (Numbers 13: 23) to discover the bounty of the land. Ta'ayush activists resorted to the ethics of transparency and the politics of exposure.

In Israel and Palestine, the cultural politics of wine is quickly becoming a bitter struggle between rival claims over national territory and cultural heritage. As the State of Israel celebrates its 70th Jubilee, its borders remain internationally undetermined and violently unstable (Newman Reference Newman, Peters and Newman2015). More than fifty years after the Occupation of the West Bank in 1967, which placed the region under military government, the state embraces wineries burgeoning in religious-nationalist settlements across the historical Green Line (the 1949 Armistice lines that mark the border between Israel and its neighbors). However, while the state labors to blur the line between Israel and the Palestinian Territories and thus normalize the Occupation (Shafir Reference Shafir2017; Allegra, Handel, and Maggor Reference Allegra, Handel and Maggor2017), activists strive to make it visible and to politicize what has recently been termed “wine-washing” (Handel, Rand, and Allegra Reference Handel, Rand and Allegra2015). Some of Israel's highest quality grape-growing areas are located within Occupied Territories, and it is commonplace for wineries to mislabel their wines in an attempt to avoid market sanctions. The 2019 European Court of Justice and the Canadian Federal Court have ruled that settlement wines cannot be labeled “Product of Israel.”Footnote 4

The Ta'ayush Settlements Wine Operation illuminates the ways in which the political construction of territoriality on the colonial frontier collides with the production of high-end wine. Steeped in the economy of land appropriation in the Negev and the West Bank, involving the dispossession of Palestinians and Bedouins and the struggle over natural resources, the case of Yatir Winery illuminates the political facets of eno-locality, defined here as the specific land regime, professional networks, and cultural system of signification that make up a “wine region.”

With bottles selling at up to US$100, Yatir is one of Israel's prestigious “boutique” wineries. It is a joint venture between the local grape growers in three religious settlements (Beit-Yatir, Ma'on, and Carmel) and Carmel Winery. Its vineyards are in the highest, southernmost tip of the Judean Hills, just at their seam with the northeastern Negev Desert. The winery itself is situated a few miles from the Green Line on its Israeli side, in Ramat Arad, near an Israelite archaeological site. It was founded in 2000 and the first wines were launched in 2003, and production gradually increased to 150,000 bottles a year. Most of the vineyards lie in Yatir Forest, Israel's largest planted forest, up to 900 meters above sea level, with several additional (unofficial) vineyards across the Green Line in the settlement of Susya, among others. The winery is managed by secular winemaker Eran Goldwasser, regarded as one of Israel's best young winemakers, and by Yaacov Ben-Dor, CEO and resident of the settlement Beit-Yatir across the Green Line.

Yatir Winery made its first appearance on the global wine scene in 2007 when its top Bordeaux blend, Yatir Forest 2003, scored 93 points with Robert Parker's Wine Advocate, which tripled its market value. It subsequently received awards from most leading wine magazines and was listed by Michelin Star restaurants across Europe and the United States. Celebrated by wine critics for their “sunny demeanor,” Yatir wines blend Mediterranean imageries of dusty forests and Oriental charm. Yatir is often referred to as “Israel's first cult wine.” Representative tasting notes read: “This superb wine is 82% Cabernet Sauvignon and 18% Merlot grapes grown in the Yatir forest; it envelops the vineyards, providing a unique terroir; Jerusalem Pine, carob & olive trees radiate an aura of calm & tranquility. Yatir Forest wine is deep crimson in color with a bouquet of ripe currants & Mediterranean herbs.”

Such a romantic depiction of Yatir's “unique terroir” stands in diametrical opposition to a violent reality of territorial conflict. Etymologically related, the concepts of terroir and territoriality display divergent cultural histories. While the first designates the palatable characteristics of place as a branded story of geographic distinction (Trubek Reference Trubek2008; Ulin Reference Ulin, Black and Ulin2013), the latter imbues the soil with political meaning (Elden Reference Elden2013). In what follows, we map the regional production of wine, knowledge, and power on both sides of the Green Line and explore the nexus of terroir and territoriality by rescaling the macro-determinations of enolocality to the microregion. The terroir-territory configuration lays bare what we term “the paradox of colonial terroir”: boutique wines are being promoted through and as part of a Zionist narrative at the same time as their production depends on Palestinian lands and Bedouin labor. While in the wine world the more specific and exclusive the terroir the better it is regarded, in contested territories naming the exact place and conditions of production can exclude a wine from the global market. In Israel, the fuzzy demarcations of wine regions and the expansionist agency of settler wineries position wine as a commoditized actor, celebrated as the convivial fruit of the land while legitimizing exclusionary claims over place and history.

Yatir is a product of this configuration. It makes a sophisticated claim for place that infuses New World sensibilities and international grape varieties, while at the same time it appropriates (Palestinian) land, valorizes soil, and transforms labor, transforming all three into exclusive commodities. Yatir circumvents the lived context of territorial conflict and depoliticizes both political space and historical time. It positions itself simultaneously within the Mediterranean transnational landscape and in a biblical site of historical authenticity. In contradistinction to the image of a romantic Mediterranean landscape, a relief of “olives and vines” (Braudel Reference Braudel1996), our analysis reconfigures a Mediterranean of wine as a Mediterranean of colonial expansion whose symbolic and material transformations are reflected in the Israeli search for rooted identity. We will conclude by showing how the dangerous liaisons between terroir and territory can help us understand other cases of “border wines” in which terroir traverses contested territories.

This paper draws on long-term participant observation, media-analysis, and interviews in wineries across Israel/Palestine, in addition to fieldwork during harvest in Yatir Winery (2012–2017) and encounters with wine professionals. Fieldwork was complemented by long-term professional training in Italy (Sommelier 3rd level, 2010) and in Austria (Wine & Spirit Education Trust, level 4, 2014–). It is part of a larger project that proposes a historical anthropology of border wine cultures by articulating the ethnography of wine production and consumption practices with the history of their expansion.

ISRAELI TERROIR? A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LOCAL WINE INDUSTRY

In the wine world, no concept is more central and controversial than the key symbol of terroir, whose proponents arguably “take it to the level of Jihad” and are conversely accused of “viticultural racism.”Footnote 5 Traceable back to the thirteenth century (Trésor 1994, XVI, 142), the French notion underpinned the continental patrimonialization of taste with the 1935 institutionalization of the French appellation d'origine contrôlée system. Toward the end of the twentieth century it became a buzzword glossing place-based product authenticity (Gade Reference Gade2004: 866; Demossier Reference Demossier2011). From the Balkans to China, wines are sold as terroir wines. Indeed, our time is marked by and marketed as “terroir fervor,” which embodies the paradox of a global trend of localism (Meiburg Reference Meiburg2012).

Here we analyze the history of the Israeli wine field and the political production of terroir in one of the region's fastest growing wine industries. Israel targets a global market eager to consume its captivating “taste of the land,” and some say it offers the best range and quality of wines in the Eastern Mediterranean, “a wine region that gave wine culture to the world, long before the vine even reached the rest of Europe” (Montefiore Reference Montefiore2011). Historically, viticulture flourished in this region from the Bronze Age through the Muslim conquests (Amar Reference Amar1995; Rogov Reference Rogov2010),Footnote 6 and remains of ancient wine presses can still be found in all parts of Israel/Palestine. Despite sporadic attempts by the Crusaders to revive the wine industry in the Holy Land, a ban on alcohol consumption fully resumed with the Mamluk conquest in the thirteenth century (Walsh Reference Walsh2018).

In the modern era, the first attempt to revive the wine industry in the region is largely accredited to French Baron Edmond de Rothschild (1845–1934), the owner of the renowned Chateau Lafite in Bordeaux.Footnote 7 While two wineries had already produced kosher wine as early as 1848 (Jerusalem Winery) and 1870 (Teperberg), his was the first attempt to modernize viticulture in the Jewish colonies. In the 1880s Rothschild funded two industrial wineries with the hope that viticulture would provide a major source of income for the region as part of the French imperial civilizing mission. Southern French varieties were planted, resulting in wines that often had a French influence. In his review of the “French wine revolution,” wine writer Adam Montifiore concludes, “Undoubtedly the Israeli wine industry was revived after 2,000 years owing to French finance and French expertise. Israeli wine was built on French roots” (Montefiore Reference Montefiore2018).

Yet Rothschild's success was short-lived. Phylloxera, a plague of aphid-like insects responsible for the destruction of rootstocks all over Europe at the turn of the century, soon destroyed all his vineyards. Slowly recovering from the phylloxera epidemy in 1906, Rothschild helped to set up a cooperative of grape growers, Société Cooperative Vigneronne des Grandes Caves Richon Le Zion & Zikhron Ya'akov Ltd. (S.C.V.), to manage the two wineries. In the 1920s its British subsidiary, The Palestine Wine Company, began marketing Kosher wines with the name “Palwin” (an abbreviation for Palestine wine) as the “genuine products of the wine growing colonists in Palestine” (figure 1).Footnote 8

Image 1. Advertisement for Palwin in Jewish World (UK, 1922).

Ultimately, Rothchild's project was shattered by three events that virtually eliminated the fledgling industry's three largest potential markets: the Russian Revolution, the enactment of Prohibition in the United States, and a ban on importing wines to Egypt. Despite the success of Palwin in the UK, most of Rothchild's vineyards were uprooted and in 1957 his son Edmond Rothschild donated his share to the cooperative, which took the name Carmel Mizrahi. It remains the largest winery in Israel with a local market share of almost 50 percent. Known since the 1990s as Carmel Winery, it also owns the Yatir Winery and others (Rand Reference Rand2015; Rogov Reference Rogov2010).

The far-reaching shift from producing exclusively sacramental wine for local consumption (known in Israel as Hammer Wine, or Yein Patishim, for its high levels of sugar and alcohol) to marketing high-end quality wine worldwide occurred over four decades and through four “revolutions”: the varietal revolution of the 1970s (importing and planting international varieties); the technological revolution of the 1980s (introducing new standards of fermentation, filtering, and aging); the enological revolution of the 1990s (integrating young winemakers trained in the New World); and the boutique winery revolution of the 2000s (artisanal micro-wineries producing world-class, terroir-driven wine). The growth of the wine industry has been exponential, expanding from a dozen active wineries in the 1970s to some three hundred today (with over two thousand wine brands), many of which are small-scale boutique wineries. The size of New Jersey, Israel reports 13,585 acres (5,500 hectares) registered under vine (WinesIsrael 2018).

A historical landmark in the chronicles of the Israeli wine industry is the 1972 visit of Professor Cornelius Ough of the Department of Viticulture and Oenology at the University of California at Davis. Ough suggested that the volcanic soil and high elevation of the Golan Heights would prove ideal for grape growing. In 1976, the first vines were planted in the Golan and in 1983 the newly established Golan Heights Winery released its first wines. “Almost overnight,” wine critic Daniel Rogov reminisces, “it became apparent that Israel was capable of producing world-class quality” (Reference Rogov2010: 6). The Golan Heights Winery was also the first to focus on planting “noble” grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, and Riesling. The (Occupied) Golan became the prototype “Wine Country,” as expressed in advertisements calling on readers to “Taste the Land.” The Golan wines were a success from the outset, not only in Israel but abroad. The 1984, Yarden Cabernet Sauvignon won the gold medal at the International Wine and Spirit Competition in London, then an unprecedented result for an Israeli wine. This success had a great impact on other Israeli wineries, which invested in building new facilities, improving technology, and recruiting young winemakers who studied abroad (Rogov Reference Rogov2010).

The technological evolution of the wine industry in the 1980s was tightly linked to two complementary processes: the emergence of a local industry of quality wines and the formation of a new consumerist middle class (Rand Reference Rand2015: 10; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2013). In addition, the growth of the Israeli wine industry in the Golan Heights was made possible largely due to massive support from the state, which was guided by political and ideological motivations. This scenario was to repeat itself two decades later in the West Bank, where wine production served economic development and also as a civil normalization of the settlement project (Handel, Rand, and Allegra Reference Handel, Rand and Allegra2015).

Parallel to its crucial role in the technological and enological revolutions, the Golan Heights Wineries have also introduced to the Israeli wine field the idea of terroir. By emphasizing the taste of place and the geographical uniqueness of the Golan region, the discourse of site-specificity has been the trigger for what we might call “the terroir turn.” In the 2000s the new interest in place-based authenticity pushed both large- and small-scale wineries to explore the quality of their terroir in Israel and in the West Bank.

The global notion of terroir is in constant dialogue with its French origins. There are two main interpretations of the concept: the first emphasizes measurable and tangible factors: such as soil, climate, and exposure, as well as agricultural factors such as vine density and harvesting techniques. The second sees terroir as inseparable from the place's social history and culture, arguing that a piece of land can possess a holistic and singular quality that is beyond the calculable (Wilson Reference Wilson1998). It is a full philosophy of place, which seeks to express rather than create terroir (Teil Reference Teil2012).

The latter approach is best represented by the INAO (French National Institute of Origin Appellations) official definition of terroir as “a social construction, concerning a natural space with homogeneous features, which is legally defined and characterized by a set of values: aesthetic value linked to landscape, cultural value linked to historical evocation, patrimonial value linked to social attachment, media value linked to notoriety” (in Fourcade Reference Fourcade2012: 529).

In the last two decades, terroir has become the organizing principle of the wine industry around the world, within what Karpik called “the new economy of singularities” (Reference Karpik2010). In the global wine field, authenticity has become the main value marker (Inglis Reference Inglis2015), relying heavily on the combination of the unique place and the “artwork” of the winemaker as an entrepreneurial craftsman. In the Israeli case, however, terroir's regime of authenticity is constantly encroached upon by the political logic of territory. If terroir is “framing and explaining people's relationship to the land […] a connection timeless as earth itself” (Trubek Reference Trubek2008: 18), then these dynamics call for exploring the politics of uncharted territories often located in contested spaces.Footnote 9

THE FUZZY BORDERS OF ISRAELI WINE REGIONS: CREATING A “WINE COUNTRY”

Viticultural zoning is central to determining the value of wine, from the appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) in France to the American Viticultural Areas (AVA) in the United States. Terroir zoning seeks to divide vineyards into parcels in which the interactions between vine and environment are as homogeneous as possible (Vaudour and Shaw Reference Vaudour and Shaw2005). The tradition of wine appellation is very old. The oldest references are found in the Bible, where the wines of Samaria, Carmel, Jezreel, and Hebron are praised. This tradition continued throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, though without any officially sanctioned regulations. Historically, the world's first protected vineyard zone was introduced in Chianti, Italy in 1716 and the first wine classification system in Tokaj, Hungary in 1730. In France, wine regions are protected under the AOC system, defined by INAO as “The expression of the intimate link between the product and its terroir: a geographic area (geological, agronomic, climatic, and historical characteristics), human artwork, and specific production conditions to get the best of the nature. The given product cannot be reproduced outside its original terroir” (in Lebrun Reference Lebrun2016: 2).

The geography of wine regions in Israel/Palestine has peculiar material and political implications. Originating from its attempt in the 1960s to seek some form of association with the European Economic Community (EEC), Israel complied with the 1958 Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration in 1965 by ratifying the Israel Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications Law. The main incentive for Israel becoming party to the Lisbon Agreement was unrelated to wine but rather was a desire to protect the JAFFA Orange trademark, which remains Israel's only Appellation of Origin to this day.Footnote 10

In 1977, the Israeli regulations on the “export of alcoholic beverages” were introduced, which divided Israel, including the territories occupied in 1967, into five wine regions. Today, as much as the Israeli wine scene has changed since 1977, its wine laws have not (Barulfan Reference Barulfan2010). Israeli wine legislation remains an eclectic assortment of ordinances applied at different, unfocused legislative levels. Unlike most wine-producing countries, Israel has no comprehensive wine law, except for the Israeli Wine Standards (standards being the lowest-ranking legal ordinances), a technically oriented do-and-do-not wine-producing manual. Israel is also unusual in that it has no wine-governing body, such as France's Institut national de l'origine et de la qualité, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau in the United States, or the Wine Australia, the Australian Government statutory authority. Therefore, no credible data is available regarding the origins of the grapes sourced by the wineries. There is virtually no quality classification system and little in the way of clear regional classification.

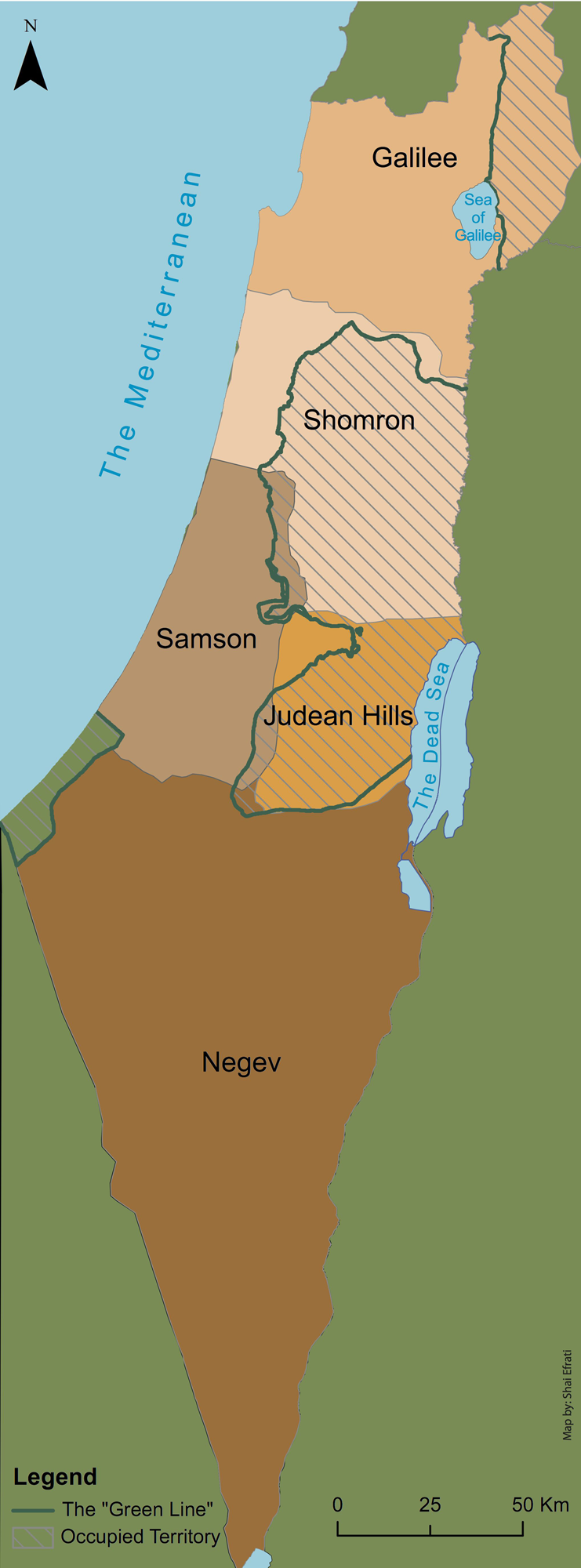

The lack of legal regulation gives winegrowers an unlimited margin for interpreting and manipulating grape provenance. Israel's loosely defined system currently has five geographical indications (GIs): Galilee, the Judean Hills, Samson, the Negev Desert, and the Shomron (Samaria) region (see figure 2). These demarcations apply solely to the exportation of wines and have no bearing on the designation of terroir typicities, since the map of winegrowing regions lacks any topographical coherence or climatic logic. The Galilee wine region stretches from the Golan Heights and the Hermon (Israel/Palestine's highest mountain, 2,200 meters above sea level) to the Sea of Galilee (300 meters below sea level) all the way to the hot and humid northern coast of the Mediterranean. Samaria encompasses the Jordan Rift Valley, the Nablus Mountains, and the Central Coast. The Samson region includes the entire plains area but also parts of the southern Hebron Hills, and the Judean Hills also include the Jerusalem Corridor west of the Green Line. Each of these five wine regions crosses the Green Line. Politically sensitive information about specific growing areas can therefore be concealed and vinous accuracy is lost.

Image 2. Israel's five wine regions (courtesy of Shai Efrati).

The geographic nomenclature of Israeli wine regions is obscure, and most Israelis could not tell you where the Samson region is, or would be surprised to learn that the Golan Heights are hiding under the innocuous reference to the Galilee. Beyond this obscurity, the future of wine regionalism has been the subject of heated debate among specialists. For instance, a conference held during the wine exposition Tec-Enology, which convened the main figures in the field, ended with a collective call to refine Israel's anachronistic, decentralized appellation system. This “jungle,” as many professionals call it, is considered a major impediment to the development of the industry. “If wine is not part of a place,” concluded Adam Montefiori, international marketing director for Carmel Winery, “there is no reason to buy wine from Israel.” Regarding the Golan Heights’ classification as part of the Galilee wine region, a former Golan Heights Wineries CEO asks: “Imagine that Israel's eastern borders were in Damascus. Would it still be Galilee? Today the Golan Heights are considered Galilee because a European Union committee wouldn't approve of a “Golan” region for political reasons. It would mean acknowledging the Golan as Israeli. But what is the connection between the Golan and the Sea of Galilee, which is 1,000 meters lower?” (quoted in Handel, Rand, and Allegra Reference Handel, Rand and Allegra2015: 1357).

This vague zoning of wine regions lends itself to mislabeling areas of contention between rival political entities. Over the last fifteen years this successful model of appropriating contested territory through wine has triggered a spillover effect and it is now replicated in the West Bank. Many settlement tourism agents consider this precedent a welcome sign of prosperity: “Just as the Golan Heights became part of the Israeli consensus because people saw that it is good, and beautiful, and fun, and it would be a pity to give to the Arabs, the same can happen in Samaria.”Footnote 11 Wine tourism plays a major role in this turn of events. Culinary travel guides such as Yesha Is Fun: The Good Life Guide to Judea and Samaria Footnote 12 celebrate “the medallion-encrusted wines in Binyamin, the branded olive oils in Samaria, a holiday cottage with a jacuzzi under the glow of the Judean desert's sky” (Eldad and Bashan Reference Eldad and Bashan2011, back cover). Today, an expanding web of “wine routes” à la Tuscany naturalizes the Occupation by weaving Jewish mythology into the contested landscape. Ben David Tours, a religious-nationalist agency specializing in “meaningful tours of the Jewish homeland,” advertises their “biblical and spiritual” wine tour as an anthropological discovery: “Meet the residents of this vibrant, Zionist region; taste their wine, and see what they have to offer the future of the Land of Israel” (quoted in Who Profits Reference Profits2011: 20).

The political implications of wine zoning are largely overlooked by the official forums on wine regionalism that we studied; they commonly make a call to “separate politics and wine.”Footnote 13 When winemakers, marketing professionals, and state agents intensively discuss the need for new demarcations, they consider only the internal, terroir-driven logic of the wine field. At a time when settlement wineries are receiving major awards as Israeli wines and are being featured indiscriminately in most wine guides, restaurants, and shops, the consensus seems to be that this political annexation is a fait accompli.

This normalizing aestheticization of the Occupation pushed alarmed activists to respond. In April 2011, a report entitled “Forbidden Fruit: The Israeli Wine Industry and the Occupation” was published by Who Profits, an independent research project previously affiliated with the Coalition of Women for Peace.Footnote 14 It exposes the balancing act of production and mislabeling, and how the current demarcations of wine regions “manage to completely obscure the internationally recognized borders of the State of Israel and consistently group together areas within the State and those in occupied territory” (Who Profits Reference Profits2011: 22).

Although the settler wineries have been successful in Israel and beyond, large producers still prefer to dissociate themselves from the colonial politics of wine in the West Bank. While the 1981 official annexation of the Golan Heights internally legitimated the public trade of grapes from the region, in the West Bank the blurring of the Green Line allows the five large wineries that control 82 percent of the market to conceal the origins of the grapes they harvest. Large wineries plead that the wine they export to the United States and Europe does not come from vineyards they draw grapes from or own outside official Israeli borders. Following Ta'ayush findings in Settlements Wine Operation, Carmel Winery's official response was that “Carmel Winery and Yatir Winery produce wine exclusively from grapes harvested within the borders of official Israel” (Mossek Reference Nissim2010).

Paradoxically, when it comes to requesting financial support from the Israeli State, the same ambiguity makes West Bank grape growers and wineries eligible for significant subsidies and direct allotments of state resources. Generous state support under the label “National Priority Region” is one reason for the exponential growth of settler wineries in the last decade (Who Profits Reference Profits2011).

“DIRTY CASKS AND OLD BARRELS”: HYBRID WINEMAKING BEYOND OLD AND NEW

In our first encounter with Eran Goldwasser, Yatir's chief winemaker and a secular Israeli, he chose to bracket his own involvement in the political economy of wine, and complained about what he termed “the Zionization of wine.” “Did you watch Eretz Nehederet last week?” he asked, “These things happen when you use wine to create roots.” The political satire Eretz Nehederet, whose title best translates as “A wonderful country,” was then the most popular show of its genre despite recurrent accusations that it was “left-wing.” The episode broadcast on 24 December 2010 addressed the controversy over freezing settlement construction. It featured an exchange between the anchorman and Rachel, the eccentric figure of a female settler and director of the Cultural Center in the fictive outpost of Assa'el.

Rachel: Why freeze construction in a place that is at the heart of the consensus?

Anchorman: You understand that your opposition is the barrier to the Peace Process? The international community puts heavy pressure to evacuate you.

Rachel: How can you evacuate a place where wine is made? Wine is the juice of the consensus! Do you know that we make wine here? It's Tuscany right here!

Anchorman: That you produce wine doesn't change the fact that in any future agreement you'll have to evacuate the Territories.

Rachel: Don't say Territories! When you say Territories you break the people apart. Say Tuscany.

Anchorman: Ok. So for parts of the Israeli public, your very presence in Tuscany is an obstacle to peace.

Rachel: What do you want from me? Talk to the Italians!

Founded in 2000, Yatir Winery was made possible by the unprecedented growth of the Israeli wine industry and by the increasing global receptivity to its wines’ specific desert-like taste: warm and intense. The winery was originally a joint venture of Carmel Winery and vintners of three religious-nationalist settlements in the region—Ma'on, Carmel, and Beit Yatir—unionized under Gadash Har-Hebron, the cooperative of growers in the Mount Hebron area. It is now owned solely by Carmel Winery but maintains complete autonomy under the supervision of Australian-trained winemaker Eran Goldwasser and managing director Yaacov Ben-Dor. The division of labor between these two actors and their contrasting perspectives on taste and place shed light on the creative tension between the “scientific” practice of oenology and what Yaacov terms “a language of values.”Footnote 15

After accepting us to work at harvest in the vineyard as ripeness samplers, Yaacov walked us through the state-of-the-art winery, pointing to its modest, functional simplicity. It does look like an industrial warehouse, a far cry from the Tuscan flourish of medieval castles, or what he called the “overdone show off” of California wineries. “We're not there yet,” he said. “We still have a long way to go.” A resident of Beit-Yatir (Metzadot Yehuda), a settlement in the “buffer zone” between the Green Line and the “separation barrier,” Yaacov “ascended” ('aliti) to the settlement with his family in 1989. “It was an ideological decision. I studied electronics but I always knew I was meant to be a farmer.” Following an initial feasibility study, the three cooperative settlements signed a partnership agreement with Carmel, which Yaacov joined toward the marketing stage in 2003. One of the first things he realized was that they were misled by the initial survey and that the winery, located in Ramat-Arad, was misplaced. The highest quality yields were to be obtained not in the existing vineyards adjacent to the winery but rather in Yatir forest, in what had been an experimental plot some 600 to 900 meters above sea level (figure 3).

Image 3: Location of Yatir Forest, Wikipedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Yatir_Forest (distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license).

The discovery of the forest's potential and the strategic decision to focus on simply “doing Yatir” led to the brand differentiation between Ramat Arad (123 acres now providing mainly Sauvignon Blanc) and the Yatir Forest vineyards (an additional 123 acres producing mainly Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Shiraz, and Viognier). The latter soon became the key to the winery's success and the source of its flagship wine, “Yatir Forest.” Ben-Dor reflected on this trial and error process with humor: “We had a French visitor who once said, what's the big deal in building a winery? The first four hundred years are tough but afterwards it runs smoothly.”

An archetypal middle-class settler, Ben-Dor would not distinguish between his professional vocation and his politics or ethics. Throughout our stay he tried to communicate to us the depth of his attachment to the land: “My worldview was that a winery should be grounded in a region. We have a world of values—our language is ethical ('erkit) in that we are Israelis from here. This is an ancient wine region. So, we try to be true to ourselves. We don't imitate more likable styles; Parker likes it or not…. We don't play this game. A rooted world of values, of here. Terroirist of sorts.”

During a coffee break in his office, Yaacov stopped in front of a large photo entitled “Beginnings” (from a series by David Harris, 1948–1968) that exhibits North African immigrants squeezed into a boat sailing from Genoa, an icon of the Zionist melting-pot ideology. “For me, this is how it all began. From here we set out to find our way. It's a people starting anew. Is this a political statement? No, it's an ethical statement” (figure 4). He then led us to the winery. Pointing to the dusty crusher at the gate, he noted: “We're the only winery suffering from sandstorms.” Throughout the time we spent in the cellars, a modern, aboveground, climate-controlled facility, we were shadowed by Rabbi Asher, the mashgiach kashrut (kosher supervisor), who made sure we did not touch the barrels and thereby disqualify the wine (figure 5).Footnote 16

Image 4: In his office, Yaacov Ben-Dor contemplates “Beginnings” (photo by Monterescu, 31 Jan. 2011).

Image 5: The Mashgiach in the barrel room (photo by Monterescu, 10 Aug. 2015).

Grapes are harvested in July and August, then separated, crushed, macerated, fermented, filtered, barreled, and bottled in a process that can last up to three years. The equipment is geared toward producing relatively small quantities and high resolution. “No gimmicks,” Yaacov told us. “No manipulations. There is one man here who controls vinification and that's Eran. I'm the production manager. I'm the earth man (ish adama).” Eran Goldwasser, the chief winemaker, shares little of Yaacov's ideological passion for the land. For him, he admitted to us, becoming a wine professional was a “logical decision,” which did not come from any intimate attachment to wine culture.Footnote 17

After a ritual post-military tour to the “east” exploring India “in search of inspiration,” Eran enrolled at Adelaide University, a center of New World wine research. “Today” he said, “I might have opted for the classical schools in Europe, but looking back I don't regret it. I believe it's better to learn in an open place, free of axioms and sacred cows.” Upon graduation he worked at Salitage Winery in Australia, and eventually returned to Israel where he joined Yatir Winery. His widespread reputation as a “gifted,” “super-modern,” “anti-tradition,” “epicurean professional interested in quality only” was unanimously confirmed by independent wine personae we interviewed.

While Ben-Dor sees his work as an integral part of an ideological mission to redeem the wilderness, which he translates to notions of terroir and identity, Goldwasser rejects the romantic connection between wine and homeland: “The link is symbolic. It's very different from a country with a continuous tradition of winemaking. The link there is unmediated. In Europe, you see vineyards that clone ten, fifty, and one hundred years-old vines. I'm not saying the link here is artificial. It's symbolic that wine was made here a thousand years ago. But it doesn't affect what we do here today! It can give us some spiritual connection, but no practical connection.”

One of the first important decisions Eran made was to focus on “the Bordelaise repertoire,” consisting of several “noble grapes”—varieties associated with the highest quality wines. Yatir's Bordeaux Blend, praised by Parker for showing “great typicity” (Reference Parker2008: 1445), is a masterful mosaic of the premium varietal wines from no less than sixty plots in Yatir Forest. Eran explained his oenological credo: “Not for nothing is the Bordeaux repertoire popular, but we thought the variety is less critical. We said, ‘Let's take the varieties that are easy to work with and see how they express our region.’ In this we succeeded. The focus is on the region and on winemaking. But we let the character float, so that people will see that our Cabernet tastes differently from the Cabernet of Galilee. This is our goal.”

Considering his reputation as a New World oenologist, Goldwasser's choice to synthesize a Bordeaux blend (one of the icons of the Old World) that “expresses the region” is far from self-evident in the context of professional winemaking traditions. The global oenological discourse stressing grape varieties as the most important aspect in determining a wine's quality and “nobleness,” rather than its terroir, means subscribing to a specific philosophical view of winemaking. This view is more typical of New World winemaking focused on varietal wine while, according to Eran, “In the Old World, grape varieties are endemic to a very unique context.” “Pinot Noir not in Burgundy,” Eran stated, “is rarely impressive.” The latter notion was made famous in the film Mondovino (Reference Nossiter, Nossiter and Giraud2004) by the owner of the traditionalist Domaine de Montille in Burgundy. Distinguishing between “vins de terroir” and “vins de marque” (brand wines), he exclaimed: “The vine is here! It's the terroir…. Brands are a part of Anglo-Saxon culture.… Here we cultivate an appellation of origin. Brands get forgotten, like people.”

Creatively mixing scripted recipes and professional dogmas from the Old World and the New World, Goldwasser concocts an original synthesis that is neither. Unbound by the burden of tradition and disposed to discover or “reverse-engineer terroir” (Paxson Reference Paxson2010), he fills the absence of a rigid wine culture in Israel with creative freedom that allows him to redefine some of the basic tenants of oenology: “Astringency is the ‘spicy’ of the wine world. The Italians and French appreciate acidity and live at peace with bitterness and tannins, much more than the New World. As for us, we practically cannot be Old World. But we try not to be blunt. If a certain crudity belongs to the New World, we try not to be like that.”

This caveat aside, Yatir's vinification practices break radically from what is deemed sacred in the Old World. “Much of what the Old World calls terroir,” he argued provocatively, “is actually unclean work—dirty casks and old barrels. It gives character to the wine, but an unnatural one. We try to do the best wine we can, but we wouldn't be able to produce commercial wine without additives.” For Eran, extreme climatic conditions call for drastic measures in a winery located at the southernmost tip of the distribution border of the grapevine in the region. He considers some practices such as irrigation, cooling, and acidification to be “given constants.” “Some wineries try to be more elegant, more European…. But you can't run away from the sun! Part of our character is maturity as opposed to freshness or elegance. That's what there is.”

The efficiency of the Yatir harvesting system allows it to simultaneously process sixty single vineyards (1.8–2.7 acres), individually monitored by a computer. The process is supervised by Dror Dotan, an agronomist who uses drones to map out the vineyards with the NDVI index system (figure 6).Footnote 18 Wines are separately made from grapes of each plot until the winemaker starts composing the blend and disposes of undesired ingredients. The select elements eventually make up the final, top blend, which is aged, bottled, and released to the market. “It's a spectacular mosaic,” Ben-Dor exclaimed. He then directed us to the storage room, where he pointed at barrels of various sizes with labels designating their origin. New and used barriques (of American and French medium-toasted oak by Tonnellerie Radoux) are marked with what appears to be an undecipherable code, but Ben-Dor guided us through their system of classification: CSMC1-10, 8/11/2010 refers to Cabernet Sauvignon from settlement Ma'on, vineyard C, parcel 1, 2010 harvest, last processed on November 2010. Similarly, PV Y A1 designates Petit Verdot from Yatir Forest, vineyard A, Parcel 1. SR M indexes Syrah grapes sourced from the subcontractor Movshowitz from the settlement Susya.

Image 6: The agronomist analyzes remote sensing measurements of a plot at harvest (photo by Monterescu, 17 Aug. 2015).

A final controversial issue of significance in production involves Arab labor. The winery publicly declares it does not employ Palestinian workers and instead opts for mechanized harvesting (an unusual practice for high-end wines). Ben-Dor explained the rationale: “We don't work here with Arabs. The agreements with the [Jewish religious] grape growers are long-term so there is no trouble. There are Thai workers and the harvest is mechanized. It's an enological decision of maximum control.”Footnote 19 And yet, in the vineyard we found ourselves working side by side with Palestinian workers from adjacent villages in the West Bank who had forged long-term working relations with the winery. By concealing their presence the winery could uphold the value of “Jewish labor” deemed central for settler viticulturists.

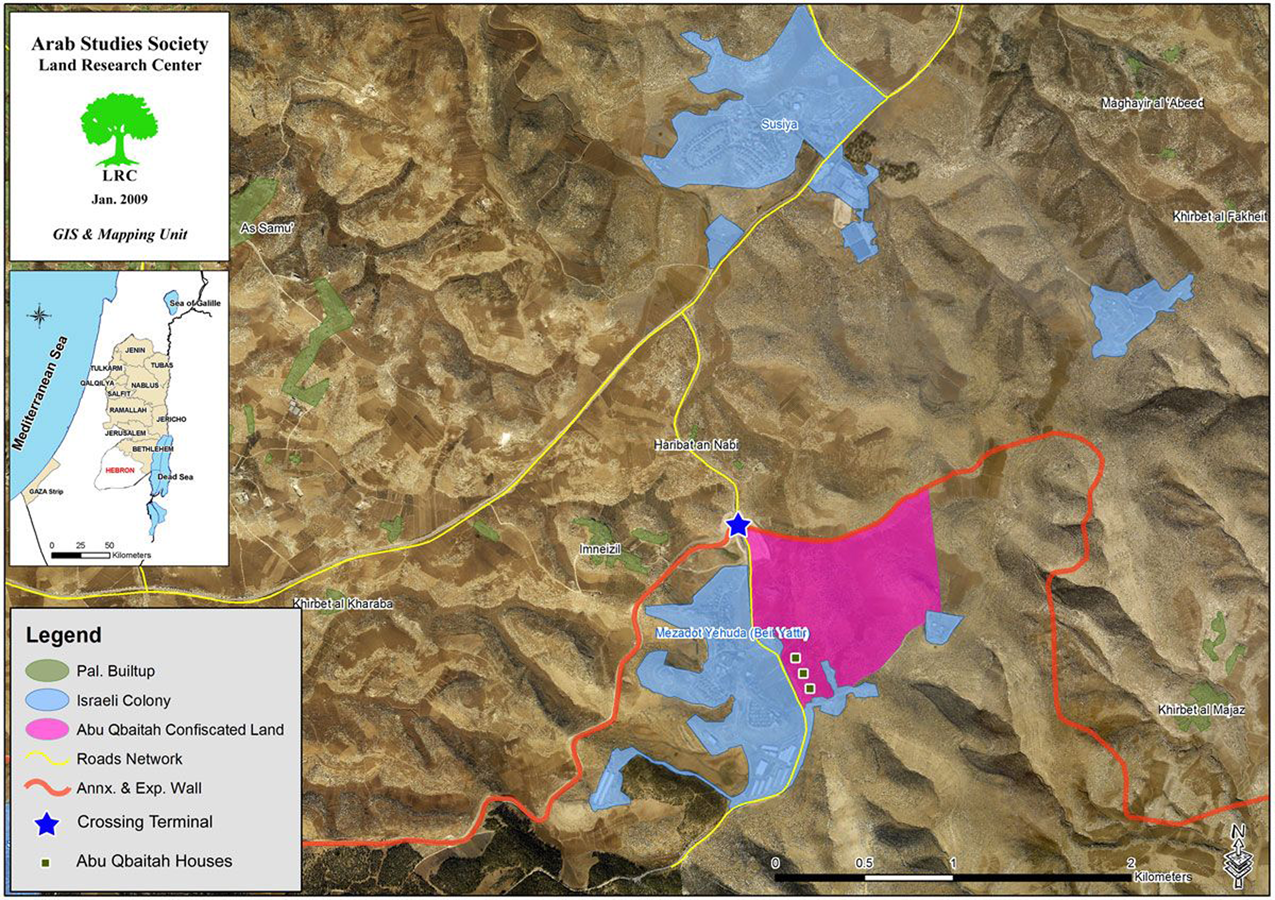

In our second year of fieldwork we volunteered as maturity grape samplers and further investigated the presence of Thai and Palestinian workers. As we harvested alongside Mustafa we conversed in Arabic and he confessed that the winery is one of the few employment opportunities available to him. Assisting his father, Mustafa must reconcile the fact that their family's livelihood depends on the same Jews who expropriated their land. Reluctant at first to talk, he gradually revealed that land belonging to his Abu Kbeita family was purchased by Beit Yatir settlement in a shady deal involving a land grab and corruption, which was taken to the Supreme Court (HCJ 383/13). Rumor has it that the process left one brother wealthy and with an Israeli ID while another who refused to sell came away poor, stateless, and harassed by the Beit Yatir settlers.Footnote 20

Yoav, another fellow harvester, is a young Jewish settler in his twenties from Beit-Yatir who was on a summer break from his civil engineering studies. He accepted the presence of non-Jewish workers as a necessary evil due to the high costs of Jewish labor, but he insisted on differentiating the “Bedouins,” who he deemed “tolerable and loyal,” from the “bad” Palestinians, who he saw as enemies. From a distance, he preferred to identify Mustafa as a “Bedouin,” although Yoav avoided communications with all non-Jewish coworkers.

THE ROARING LION OF JUDAH: BRANDING TERROIR AS A HISTORICAL CLAIM

Critical researchers have unraveled the economic dynamics that position terroir as commodity fetishism that endows wines with an aura of primordial romanticism (Ulin Reference Ulin, Black and Ulin2013). In anthropological terms, we define the Old World concept of terroir as a form of essentialist relativism, which sanctifies difference through an idiosyncratic taste of timeless place. We take up Black and Ulin's (Reference Black, Ulin, Black and Ulin2013: 7) call to view wine as a point of departure to contested traditions “too often ignored or eclipsed by narratives devoted to the commodity itself.” As Ulin convincingly argues, terroir must be denaturalized to reveal “the historicity of social relations upon which the production and consumption of wine is based” (Reference Black, Ulin, Black and Ulin2013: 67).

The Old World notion of terroir positions long-term traditions as part of the ecosystem. In New World winemaking, however, terroir is interpreted with an emphasis on the measurable characteristics of place: climate, soil, slope, and recently also microbes and fungi. This difference also entails the role of the winemaker: “non-interventionist” terroir expression in the Old World as opposed to voluntaristic human agency, talent, and craft. While the Old World embraces terroir determinism and essentialism, for New World practitioners terroir is just another tool in the winemaker's toolbox. To sum up these differences, California winemaker and writer Randall Grahm (Reference Grahm2009: 306) distinguished between “vins de terroir” and “vins d'effort.”

Straddling both the Old World and the New World, since the 1980s the wine industry in Israel/Palestine has used terroir mainly as a marketing tool rather than as a systematic principle of winemaking. In professional wine circles, the Israeli haphazard use of the notion of terroir is under attack. At Haim Gan's wine center, “The Grapeman,” terroir is criticized as no more than a fiction. “What is Israeli terroir?” Gan asked, “It's a sales tool! It's a rubber stamp.”Footnote 21

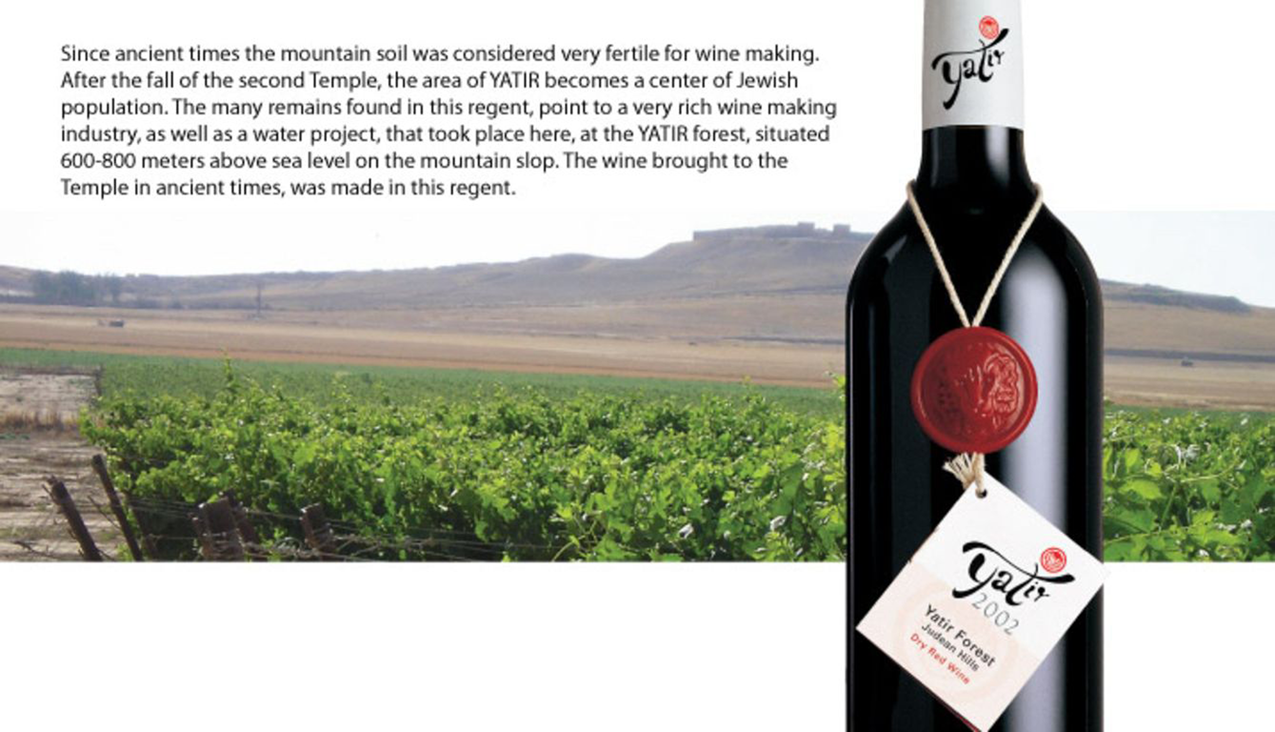

Yatir embodies the debates around terroir skepticism, which criticize Israeli terroir as a “folktale” and as “military heritage” (moreshet krav). For Gan, one of Israel's leading wine personae and a sought-after panelist in international competitions, the super-modern skills of Yatir's winemaker bring terroir to its knees: “This is not terroir. Goldwasser made his own terroir. He subdues the wine. Of course, he's a first-class chemist, but what's the point here? These folks, they'll tell you stories about terroir because it's a trend. A figure of speech. It's an amorphous word. Plastic.” Bridging the gap between national history and the international market, the process of branding Yatir's wine illuminates the commodification of terroir and its political implications. Yatir's official ideology invokes terroir as a historical claim, which reinserts the new industry into a biblical temporality of autochthony and rootedness. The managing director framed his life-project as part of the place's ancient roots: “The region has 180 ancient wine presses. Three thousand years ago, under David's Kingdom, Yatir was the gate to ‘the populated land of Canaan.’ The Prophet Hosea says, ‘I found grapes in the desert.’ He wants to give it a distinctive mark” (figure 7).Footnote 22

Image 7: Yatir wine as Temple wine (courtesy of Yatir Winery).

Despite recurrent attempts by Carmel Winery to stick to the borders of “official Israel,” Yatir resorts precisely to the “connection with Judea” as the source of its terroirist distinction. Moreover, in private conversations and interviews with right-wing media, the collaboration with settler viticulturists becomes a matter of fact. Celebrating Yatir's inclusion in Hugh Johnson's popular guide (Reference Johnson2009), Ben-Dor emphasized in an interview with religious-nationalist Channel 7 its global appeal to Jewish clients: “That our farmers and grapes are from Judea and Samaria (Yesha) does not interfere. Our logo is the lion, the symbol of the tribe of Judah, and our goal is to bring the beauty of the Land of Israel to the whole world” (Toker Reference Toker2009).

To substantiate this historical claim and to enhance market differentiation, an advertising agency (www.baruchnaeh.co.il) designed a softened image of the Lion of Judah as Yatir's commercial logo (figure 8). A powerful signifier, the Lion was the symbol of the kingdom of Judah (and remains in Jerusalem's coat of arms). The icon draws on a passage in the Book of Genesis (49: 9) in which the patriarch Jacob (“Israel”) blesses his son Judah as a “Young Lion” and declares his supremacy over the nations for eternity. “It's a Hebrew worldview, very local patriotic,” Ben-Dor told Monterescu, pointing at the forest and the Judean Hills. “It helped us define our identity and receive exposure. Ehud Banay sings, ‘Speak the language of the Hebrew-man.’ We are the Yatir-man! We have here an Old World terroirist perception combined with the precision of the New World. When you come here you don't look for Provence or Tuscany.”

Image 8(a): The Lion of Judah: Yatir's Logo (courtesy of Yatir Winery).

Image 8(b): Designing the lion of Judah (courtesy of Yatir Winery).

Yatir's commercial branding semiotically normalizes the politics of territoriality and circumvents the “separation barrier” overlooking its vineyards. “I just leave the border and the fence aside,” Ben-Dor insists; “It doesn't matter if I'm a settler or not.” When we came to the topic of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movementFootnote 23 campaign later in our conversation, Ben-Dor actually admitted that the heated debate over the legitimacy of the West Bank grapes only gave Yatir good publicity in a highly competitive market: “What people don't understand is that in a world of dense branding when you stab someone on one side it can backfire. So in Malmö we won't sell. Ok. But in Texas we'll get in precisely because of that.” When we met again a few years later, as the BDS debate reverberated in Israeli winemaking circles, he happily reported growing international sales and media exposure despite and partly due to the hostile atmosphere in Europe.Footnote 24

Though less passionate than Ben-Dor, who confessed feeling “very comfortable with the cover story” that “comes from an inner place,” Eran Goldwasser did not contradict him: “With wine one has to invent a story. That's how it is. You won't find a wine without a story. This is the extra you pay for just another fermented grape juice. In Italy it's the DOC system. This notion of terroir is all about branding.”

While every wine has a story to tell, not all stories are equivalent. Other critics are far less tolerant toward Yatir's efforts to depoliticize the context of production. For Haim Gan, this success story conceals an act of slavery: “It's outrageous how he oppresses slaves […] that he irrigates the grapes and a spit away Bedouin kids have no drinking water. Look, Arabs plant olives to say the land is theirs, Jews redeem the land by the verse, ‘Thy wife shall be as a fruitful vine by the sides of thine house.’ When they [temporarily] froze construction in the Territories, the settlers planted 1,000 dunams of vine. It's a claim on the land and they mobilize religion.”

What Gan alludes to is the ongoing expropriation of Palestinian land by the settlements that supply Yatir with grapes. In this way, with the expansion of settler vineyards the territorialization of terroir comes full circle. In addition to the aforementioned confiscation of Abu Kbeita's land—lying cheek by jowl with Beit Yatir (Nieuwhof Reference Nieuwhof2012; figure 9)—another case involves Elad Movshowitz, a winegrower in the settlement of Susya who supplies Yatir with grapes. In the course of four years, Movshowitz tripled the size of his vineyards at the expense of Palestinian land with the official support and funding of the Settlement Department of the Zionist World Organization. Later, his son grabbed seven more dunams and near Susya established his own winery (Drimia Winery), famous for its award-winning top wine Sfar (Hebrew for “frontier”).Footnote 25

Image 9: Palestinian confiscated land and settlements adjacent to Yatir Forest (courtesy of the Arab Studies Society).

Gan's critique notwithstanding, he chose to include settler wineries in his The Comprehensive Guide to Israeli Wine (Gan, Cooper, and Koren Reference Gan, Cooper and Koren2016), as opposed to Gal Zohar and Yair Gat, authors of The New Israeli Wine Guide (Reference Zohar and Gath2014), who refused to include wines outside the Green Line (yet featured the Golan Heights). Gan is likewise not innocent of a romantic form of Orientalism. Bringing his take on the predicament of the Palestinians in South Mount-Hebron to a grand finale, he concluded: “Have you tasted their food? Intense-flavored za'atar and sumac.… Rough, potent land.… The Palestinian is more connected to the land than I am. He's the real terroirist!”

LIQUID MEDITERRANEANISM: DEPOLITICIZING CULINARY IDENTITY

The flip side of the exclusionary and ethnocentric narrative on Jewish history and enolocality, represented by the Lion of Judah, can be found in the yearning to Mediterraneanism as an expression of normalized belonging to the region. For most Israelis, the road leading to Europe, the United States, and the wider world passes through the Mediterranean but bypasses the treacherous grounds of the Middle East. The public debate on “the Mediterranean Option” (Ohana Reference Ohana2011) comprises two rival perspectives, which view Israel as either a settler-colonial project or an integral part of the Mediterranean space. Fulfilling the latter wishful thinking, the official booklet Wines of Israel: Where the Mediterranean Begins, produced in 2019 by the Israel Export & International Cooperation Institute (Reference Export and Institute2019), invites wine lovers to “taste the warm sunlight and tempering breezes of Israel, where the Mediterranean begins.”Footnote 26 The prospects of the local wine industry are framed within a shared civilizational geography of region-making, “where the Fertile Crescent meets the Mediterranean, wine was produced 5000 years ago … in the same soil under the same sun.”

For Israeli wine professionals, the Mediterranean question is inextricably linked to problems of regional ecology, gastropolitics, and the crystallization of taste. The Mediterranean as a climate, rather than a political construct, was the immediate frame of reference for all the winemakers, grape growers, sommeliers, and wine dealers that we met. Put in terms of an organic whole, Haim Gan considers the living Mediterranean as “part of our historical mistakes”:

We forgot we are in the Mediterranean basin. If instead of “grazing in foreign fields” in the cold north of France, we had looked here to our neighbors like in Lebanon, which has the most interesting wines in the Middle East…. Why do I need to go to New Zealand to bring a bird I have here? We now pay the price! There's nothing but Mediterraneanism because here is where we live. This is the climate, these are the aromas, this is the sea.… This is the terroir. He who doesn't connect to the land, it will spew him out, as it did throughout history.

Gan's Mediterraneanism (yam-tichoniyut) is music to the ears of most Israeli winemakers. Still under the sign of the Mediterranean qua climate region, Ben-Dor identifies the microclimate as a means of distinction, which resonates with the official attempts to reposition Israel in and of the region: “The image of Israel as a Mediterranean country fits beautifully with our story. We bring to Mediterraneanism our local patriotism.… There was a Brazilian dealer who brought wine from Lebanon. I told him, ‘The place of our wine is not the Kosher shelf. Put it next to Lebanon.’ This is our natural place. Much more natural than placing it next to Bordeaux.” Geographically speaking, Yatir Winery lies on the “desert frontier,” a crossroads between the Negev Desert, the Judea Desert, and the humid Mediterranean region (figure 10). This is the meeting point between what Braudel called “the landscape of vines and olive trees” and the “mountain world” (Reference Braudel1996: 27). Looming over these drastic contrasts, however, is Braudel's insistence on the unity of the region, rhythmed by “the even light, which shines at the heart of the Mediterranean” (ibid.: 231).

Image 10: Desert wine between the mountain and the sea (authors’ photo, 17 Aug. 2015).

Subscribing to this unifying view of the Mediterranean, Ben-Dor conveniently ignores the predicament of his immediate neighbors while insisting on the links between Israel and Lebanon, which make up the “New Middle East in its true sense”: “I'm a Mediterranean wine. I have hot summers and cold winters in Mediterranean terms. My wine is dark. Take this terroir and go with it. From this perspective I'm closer to Lebanese wine than to Tuscan wine. This is the New Middle East in its true sense.” He then described his experience in an international wine exhibition in Bordeaux, where he approached the Lebanese booth but “they were afraid to talk to me.” “It's the same with Arab fellahin here,” he concluded. “We used to have friends in Beit Ummar [a village of grape growers], but when we visited them after the Intifada they hid. We took our weapon and went to greet friends,Footnote 27 but each time we showed up they were not home.”

The imagined connectivities espoused by Gan and Ben-Dor have, of course, little to do with the political realities of the region, but they do express the translocal geography of wine, which transcends the geopolitics of nations and states (Brickell and Datta Reference Brickell and Datta2011). Looking inward, our interlocutors have argued repeatedly that before Israel can integrate into the region it must find its own identity. The following narratives point to the profound yet indeterminate link between a wine culture, a collective sense of self, and Israel's place in the Mediterranean. At Yatir, chief winemaker Eran Goldwasser was determined to see no Israeli “sense of identity” in all things vinous:

It just doesn't exist; neither historically nor on the ground. No sense of identity. I wonder why…. In contrast to hummus and olive oil that express roots, wine entered our culture recently and from the top down. And because we are a nation of immigrants, we desperately look for roots. The whole Zionist dogma initially tried to do it by force, but roots are made from below and because hummus and oil are more lowbrow ('amami) they take root more easily. Wine might always have this pretentious aura that prevents it from becoming authentically Israeli.

Eran's sociological explanation points to the limited potential of developing an “authentic” wine culture in Israel. The paradoxical Israelization of hummus and olive oil, both indexing the native Arab culinary heritage but also resonating with an indigenized Sabra repertoire, succeeded where wine has failed (Hirsch Reference Hirsch2011). Surprisingly reflexive for a practitioner working on the political frontier, Eran identifies the real problem of wine culture not in quality but in its politicization and commodification: “Wine culture in Israel comes from the wrong places, from pretentious and emulative places. Wine is an inverse pyramid with no basis in everyday life, a pseudo-philosophy. The problem is the Zionization of wine and wine judgmentalism. There's a branding culture but no wine culture.” Despite this critique, for Eran as for most of our interviewees, a national culinary identity is bound to crystalize. This process, he insists, is a spontaneous emergence that cannot be engineered: “It's inevitable that it will happen. For example, Israelis like a specific kind of olive oil that they learned from the Arabs. It's green-colored, strong, bitter, spicy, and herbaceous. That's what Israelis like. Without guidance.”

Whether Israel will develop a culinary cultural identity remains an open question. Haim Gan suggests that Israel is a “laboratory” for the “wandering Jew”: “We're a field of experiments. But what will come out of this distillate? Will there be Israeli food or wine? A mature character that will make peace and won't feel a wandering Jew anymore? This maturity is what's missing. But I believe we're getting there. It's a search.”

EXPAND, DIFFERENTIATE, INDIGENIZE: BETWEEN BORDER WINES AND COLONIAL TERROIR

Wines have distinct political biographies and the social life of terroir exemplifies their complicity in the history of nationalism, imperialism, and colonialism. Born in Europe to a continent with millennia of wine tradition, the terroir concept has been re-rooted in the New World, while preserving scents of French origin. If terroir is a way of connecting place, human actors, and food, it takes on different shapes in respective contexts. “Moving beyond the idea that ‘terroir is adaptable,’” Cappeliez argues, “wine actors articulate terroir's normative principles as constant, but describe terroir's natural and human practices in locally contingent ways, nuancing our understanding of stability and change in how culture unfolds within a globalized cultural context” (Reference Cappeliez2017: 24).

Currently, the global geography of terroir is predicated upon several regimes of place-based authenticity, tradition, and creative freedom: First is the archetypal terroir associated with the Old World, which defines the primary model for vinous authenticity (e.g., Burgundy). Here the role of the winemaker is limited to humbly transmitting the essence of the land itself with minimal intervention. The second regime of authenticity looms large in New World wine industries (e.g., California, Australia, Chile, South Africa), which consider terroir as secondary to the professional skill of the winemaker. Defined largely by its measurable variables rather than tradition, terroir is only one element in the winemaker's toolkit. These are the two archetypes that Graham labeled “vins de terroir” and “vins d'effort.” Third is a global regime of authenticity that emerged as a backlash to the mass production of wine and other types of food, dubbed “terroir fervor” by Master of Wine Meiburg (Reference Meiburg2012). Now there are New World projects of inventing or “reverse-engineering” terroir claims to place-based taste, not only in wine but also in mescal, cheese, and other artisanal agricultural products with global markets (Paxson Reference Paxson2010; Beriss Reference Beriss2019). The last regime of authenticity is emerging in places like Israel/Palestine that suggest a commitment to an ancient terroir but have no viable sources for comparison and calibration.Footnote 28 The reverse engineering efforts are thus both more rigorous (based on scientific research) and more speculative (due to the lack of an unidentifiable origin and continuous tradition). The degrees of freedom for wine creativity and historical interpretation make it possible to inject a political story into the final commodity. Like Theodor Herzl's utopian novel Altneuland (Old-new land), this last configuration pursues an Old-New regime of authenticity that is implicated in settler colonial projects of political territorialization. Under the slogan “Timeless Israel,” the promotional campaign Wines of Israel describes “a 5000-year young” wine industry: “In Israel, one feels that time is compressed. There is a strange combination of reverence for roots and a pioneering ‘anything goes’ spirit of creativity. In this thoroughly modern country the past doesn't intrude on the present, it exists simultaneously right alongside—in the ancient wine presses and limestone storage caves buried within newly planted vineyards. The past doesn't dictate, it inspires”(Israel Export Reference Export and Institute2019).

Terroir work is border work. It defines a quality space, which sometimes collides with political borders. However, the very significance of borderness differs in Old World and New World contexts. Historians and geographers distinguish between borders and frontiers (Lamar and Thompson Reference Lamar and Thompson1981), or alternatively between European and American notions of frontier (Boal and Livingstone Reference Boal, Livingstone, Kliot and Waterman1983: 139). The border in the European sense signifies fortified lines separating well-defined communities. The New World frontier, on the other hand, is perceived as a contact-zone between civilization and wilderness. While the border, associated with the European Old World, is restrictive, segregative, and static, the New World frontier is generative, expansive, and dynamic (ibid.).

The historical disjunctures between European borders and the New World frontier are made visible in the divergence between border wines in Europe and frontier wines in settler colonial settings. On the one hand, linear borders, which separate two mutually recognized political entities, engender border wine regions as a bone of territorial contention. In this case, one terroir is split between two rival states struggling to circumscribe the official designation of origin to the boundaries of the state. We call this type “terroir contraction,” where the borders of terroir are made to fit the political borders of the nation-state.

On the other hand, the settler colonial frontier operates as an open zone of indistinction and a site for expansionist fantasies, which reject rival claims for sovereignty and ownership. Frontier wines are in this way part of the colonial production of space: they instantiate the efforts to self-indigenize and put down roots in an imagined terra nullius (Veracini Reference Veracini2010). The “constructive ambiguity” of Israel's border regime (Benvenisti Reference Benvenisti1988: 49) is also reproduced by the fuzziness of the local wine appellation system. We call this configuration “terroir expansion,” whereby the allegedly natural borders of terroir legitimate the expansion beyond the contested borderlines of the colonial state.

In border wine regions where terroir often traverses national territories, cultivating nature becomes a political statement. Border wine regions such as Tokaj illustrate the articulation of terroir contraction. Stretching across the border between Hungary and Slovakia, the 1737 Tokaj appellation is arguably Europe's second classified wine region. Admired by the French King Louis XIV as “the wine of kings, the king of wines,” the region consists of twenty-eight named villages and 11,149 hectares of classified vineyards, of which only 5,500 are currently planted in Hungary, and seven wine-growing communities cultivating 908 hectares in Slovakia. Due to the history of Tokaji aszú, the world's oldest botrytized sweet wine, Tokaj was declared a World Heritage Site in 2002. A classic case of an ethnic wine, Tokaj is the only wine that features in a national anthem (Robinson Reference Robinson2006).

During most of the twentieth century, Tokaji languished (ibid.: 699). Its reputation suffered with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 and the disappearance of vaunted Imperial Tokaj. The World War II liquidation of Jewish merchants, who played a crucial role in distributing wine in Central Europe, also contributed to the decline of viniculture (Stessel Reference Stessel2014), which further deteriorated under Soviet domination. Since the 1990s, as part of postsocialist efforts to crystalize national culture—among others by means of creating a local classification of culinary heritage known as HungarikumFootnote 29—Hungary has won several lawsuits over the use of the Tokaji name (against Italy, France, Australia, and Serbia). But in 2013 the European Court of Justice rejected Hungary's appeal to delete Slovakia's designation “Vinohradnícka oblasť Tokaj” (Tokaj Wine Region) from E-Bacchus, the register of designations of origin and geographical indications protected in the EU. Consequently, under the current EU legislation, the wine-growing region of Tokaj is shared by both Hungary and Slovakia. Wine producers from both the Hungarian and the Slovak Tokaj regions may now use the Tokaj brand name. In Hungary, some went as far as describing the ruling a “Trianon for wines.”Footnote 30

Hungary's efforts to limit the authorized use of the name Tokaj to Hungarian territory represent a clear case of “terroir contraction.” They reflect a logic of an Old World border, not a settler colonial frontier. The story of a divided wine region trapped between two nation-states exemplifies how the dominant logic of territorial nationalism evolved in a structure of symbolic amplification and schismogenesis (Sahlins Reference Sahlins2005) with increasing differentiation of national cultures and spaces. The case of Tokaj instantiates a European strategy of patrimonialization and nationalization of wine. At present, Slovaks and Hungarians compete over the region's symbolic and market value, while sharing an ambition to revive the industry and make Tokaj great again.

In contrast to border wines, the Yatir wines straddling the Judean Hills and South Mount Hebron in Israel and Palestine belong to a larger category of frontier wines. Just like historical Zionism used the terra nullius slogan, “A land without a people for a people without a land,” to justify its territorial claims, Israeli winemakers now seem to follow the maxim “terroir without a territory for a territory without terroir.” The complementary terroir-ization and territorialization of the border is the defining feature of the contested Israeli winescape. Notwithstanding the longue durée of three millennia of Jewish history, the Israeli wine world displays a deep affinity with other settler colonial spaces and New World wine philosophies: beginning anew armed with science and technology. The Israeli case in this sense represents an Old-New World hybrid in which ancient histories feed a contemporary exclusionary title to contested territory. Vis-à-vis Palestinian indigeneity, Israel sets a claim of primordial autochthony: ancient origins, blank separation, absolute present.

Taking an active part in the violent remaking of contested spaces and gastronationalism (DeSoucey Reference DeSoucey2010), “terroir” is both phenomenology and practice organized around the temporality and spatiality of soil. As Appadurai points out, “‘soil’ needs to be distinguished from territory … while soil is a matter of a spatialized and originary discourse of belonging, territory is concerned with integrity, surveyability, policing and subsistence” (Reference Braudel1996: 46–47). On the colonial frontier the depoliticization of soil and the temporality of terroir serve to normalize the governmentality of territory.

The “amorphous” plasticity of its key concepts allows wine to index both authenticity and connectivity—a redemptive return to the “Land” but also a strange “New Middle East” with “endemic” links to Lebanon. It is simultaneously the “juice of consensus” and the “Jewish way.” Oriented toward the distant past or the indefinite future, the temporal aura of terroir obfuscates the colonial politics of the frontier and, paradoxically, legitimates the forbidden fruit. The result of the Yatir modus operandi is an ultramodern, officially Jewish-only space that indiscriminately processes grapes from vineyards on both sides of the Green Line. The Yatir Forest blend infuses multiple vineyards and diverse terroirs in one liquid, which is as enchanting to the wine connoisseur as it is disturbing to the critical observer.

In Wine and Philosophy, wine critic Matt Kramer refines his phenomenological definition of terroir as “somewhere-ness” (Reference Kramer, Allhoff and Draper2007: 226). This poetic definition captures the persistent ambiguity of wine's universal claim for translating the local. What Trubek aptly terms “a taste of place” (Reference Trubek2008) reflects more than a marketing strategy or a territorial possession; it is a mode of being in the world, which can provoke “a feeling that I can only describe as akin to homesickness, whether or not it is for a home that may only exist in your imagination” (Grahm Reference Grahm2006).

This imagined homesickness, the desire for the land, the passion for territory (Feige Reference Feige2011; Neumann Reference Neumann2011) is a pivotal theme in Zionist phenomenology. Conceptually split and historically troubled, its imagination of home conveys a sense of place that “is ambivalent, dialectic and paradoxical, moving between poles of place and non-place” (Gurevitch Reference Gurevitch2007: 8). Implicated in but not reduced to the political economy of colonization, this peculiar notion of placeness, or Mekomiyut, persistently reenacts the unresolved tension between the longstanding yearning for the “promised land” and the ambivalence that Jewish settler-colonialists feel about actually becoming the place's “natives.” As the Yatir case reveals, the anthropology of things vinous positions Israeli terroir both in and out of time and place. Circumventing local space, it is projected onto a mythical biblical past of lost and renewed rootedness. Seeking to “undo Palestine,” it steps over the Arab Middle East by conjuring up the Mediterranean as a gateway to the global market and to cultural normalcy.

Israeli winemakers devise a depoliticized alternative to terroir that looks to the Mediterranean region writ large as the basis of regional wine's character (climate-based organoleptic properties) and (pan-cultural) identity. Resonating with the strategies famously subsumed in The Corrupting Sea (Horden and Purcell Reference Horden and Purcell2000) under three maxims—diversify, store, and redistribute—Yatir and other Israeli frontier wineries have developed their own principles of action that we can identify as: expand, differentiate, and indigenize. As embodied material culture, producing and consuming alcohol constitute “practices through which personal and group identity are actively constructed, embodied, performed, and transformed” (Dietler Reference Dietler2006: 235). In this sense, both the commoditization of wine and the commodification of terroir play crucial symbolic and material roles. The prescription for coping with the challenges posed by topography and demography is extended to neutralize the Palestinian Other and naturalize the fruits of the Occupation. Following the logic of schismogenesis (both complementary differentiation vis-à-vis the Palestinians and symmetrical vis-à-vis Mediterranean Europe), wine, hummus, and olive oil are made to become emblems of Israeli culture in the making (Sahlins Reference Sahlins1999; Bateson Reference Bateson1972; Grosglik Reference Grosglik2011; Hirsch Reference Hirsch2011). Wine signifies at the same time historicity and progress, and functions as “a medium of exchange, a mediator” (Algazi Reference Algazi2005: 236; Dietler Reference Dietler1990) between a myriad of publics and actors in the Mediterranean and beyond, ranging from the (invisible) neighbor to the (welcome) pilgrim-tourist. Terroir expansion mirrors the ambiguity of colonial frontiers.

Further research could investigate how, across the Green Line, Palestinian producers are diligently reformulating the territorial logic of baladi terroir, due to, among other factors, the global BDS efforts).Footnote 31 For example, the UK-based Zaytoun CIC markets olive oil and majhoul dates as “artisanal food reflecting Palestinian culture,” which celebrates the “deep connection of a people to their land.”Footnote 32 In the West Bank, Taybeh Winery and Brewing Company invites consumers to “Taste the Revolution” (Meneley Reference Meneley2014: 69). Similarly, under the title “Heritage Endures,” Canaan Fair Trade “seeks to empower small and marginalized Palestinian producer communities caught in the midst of conflict through organic agricultural production.”Footnote 33 The indigenization of gastro-authenticity through global networks operating in conflict zones opens up a space for a comestible anthropology that responds to the claims of terroir as it refashions the claims of territory (Saleh Reference Saleh2008; Trubek, Guy, and Bowen Reference Trubek, Guy and Bowen2010).

The study of terroir extends well beyond the scope of Israeli-Palestinian territorial politics and poses a series of challenging opportunities for contemporary historical anthropology. Historically, the cultural concept of terroir is based on a “secular conviction of a tight objective relationship to the farmed environment” (Vaudour Reference Vaudour2002: 119), yet in specific contexts it is often infused with religiosity and hallowed nationalism. Predicated on irreducible site-specificity, it has become of late a trope of global currency, albeit one largely boxed in the Old World–New World dichotomy. Beyond old and new, however, a third world of wine is emerging in the Global South, the European periphery, and the Eastern Mediterranean. With China and India now ranking among the world's ten largest wine consumers, new wineries are emerging in Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, transforming the traditional globe of wine production. Following the sensational boom of château-building in territories outside the Euro-American winescape (such as Chateau Indage in India and Dynasty Wine in China), a critical anthropology of border wines and frontier wines can profit from an analysis of emerging culinary cultures and their respective claims for terroir and territory at various scales. Distilling memory and place, liquid anthropology is yet to mature but it reveals a promising aging potential.