Health inequality exists across socio-economic groups in relation to several health conditions, many of which can be directly attributed to differences in health behaviour(Reference Marmot, Allen and Bell1). The consequences of health inequality can be far reaching affecting not only the individuals themselves but also broader society as a whole(Reference Woodward and Kawachi2). Evidence suggests that despite overall improvements in population health, the gap in disease rates between socially advantaged and disadvantaged groups continues to increase, perpetuating health inequality(Reference Bennett, Pearson-Stuttard and Kontis3). This health ‘gap’ is further exacerbated as a result of multiple ‘risky’ health behaviours that are increasingly likely to be adopted by the least privileged members of society(Reference Ding, Do and Schmidt4).

To tackle health inequality, interventions should consider the social context in which specific health behaviours manifest themselves. For example, why do individuals and specific groups of the population engage in health damaging/health promoting behaviours and why do other groups not engage in these behaviours?

Research suggests that early lifecourse interventions have the potential to reduce health inequalities and that critical time-points exist during which health interventions may prove more effective(Reference Marmot, Allen and Bell1). Parenthood is a crucial point in the lifecourse during which disadvantaged groups may be more perceptive to health interventions such as smoking cessation(Reference Graham and Der5). Similar patterns might be true concerning breast-feeding and alcohol use. We focus on two key health behaviours: breast-feeding and alcohol use according to social and domestic circumstances.

Breast-feeding and social context

Breast-feeding has been found to benefit both mother and child(Reference Horta, Loret De Mola and Victoria6–Reference Chowdhury, Sinha and Sankar8). For the child, breast-feeding provides infants with essential nutrition and protection from infection as well as fostering early positive growth and development(Reference Chien, Howie, Woodward and Draper9–11). For the mother, it is associated with reduced rates of ovarian and premenopausal breast cancer, and lower rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes and CVD(Reference Binns, Lee and Low12). Nevertheless, only 34 % of mothers in the UK breastfeed up until their child is 6 months old(Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows13). Whilst the number of women in the UK who initiate breast-feeding is high 81 %, this dramatically decreases to 55 % by 6 weeks and 34 % breast-feeding by 6 months(Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows13). Furthermore, there is considerable variation in breast-feeding rates according to social circumstances(Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows13). Individuals living in more advantaged social circumstances are more likely to adopt a broad range of protective health behaviours including breast-feeding(Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows13).

Alcohol use and social context

The majority of adults in Great Britain (57 %) aged 16 years and over drink alcohol and do so in a manner that does not pose considerable health risks(14). However, alcohol misuse in the minority has significant cost implications for society – such as reduced productivity(Reference Mohapatra, Patra and Popova15) and increased demand on the National Health Service. In England in 2017/18, there were reportedly 1 171 253 alcohol-related admissions(16), and the estimated cost of alcohol-related harm was £21–£52 billion(17).

Patterns of alcohol use have been found to be influenced by socio-economic status(Reference Grittner, Kuntsche and Graham18), and those in disadvantaged circumstances appear to be more harmfully affected by alcohol misuse than those not living in disadvantaged circumstances(Reference Bellis, Hughes and Nicholls19,Reference Katikireddi, Whitley and Lewsey20) . Patterns of alcohol use among mothers have also been found to exist according to social and domestic circumstances(Reference Baker and Graham21) and evidence points to the increased likelihood of disadvantaged social groups engaging in health-damaging patterns of alcohol use(Reference Baker22).

Breast-feeding and alcohol use

There is a dearth of information cited in UK alcohol guidelines in relation to alcohol use whilst breast-feeding. The 2016 report on alcohol guidelines(23) considers alcohol use whilst pregnant but stops short of providing clear guidance for breast-feeding mothers. Much debate exists in the research literature surrounding the safety of alcohol consumption and breast-feeding. Several authors point to abstinence or a ‘better to be safe than sorry’ approach, recommending that women do not breastfeed if they drink alcohol citing the debate around how much and how long alcohol remains in breastmilk(Reference Haastrup, Potteg and Damkier24). Others suggest that moderate levels of alcohol are acceptable provided the timing of feeds is considered; often stating that women should refrain/limit alcohol consumption for approximately 2 h before breast-feeding(Reference Haastrup, Potteg and Damkier24). Perhaps unsurprisingly, research suggests that mothers are often subject to conflicting health messages(Reference Elek, Harris and Squire25). Despite current guidelines advocating abstinence from alcohol consumption during pregnancy(23), recent statistics suggest that between 40 and 80 % of women in the UK drink whilst pregnant(Reference O’Keeffe, Kearney and McCarthy26). Whether or not these patterns persist among breast-feeding mothers remains unknown. Therefore, exploration as to whether social and domestic factors influence mothers’ alcohol use whilst breast-feeding is warranted and may provide the basis upon which to explore mothers’ decision-making processes.

This paper identifies patterns of alcohol use among mothers as a sub-group of the population to illuminate what social factors influence alcohol use among breast-feeding mothers. In doing so, we provide information relevant to both economic and societal factors: ‘patterns of alcohol consumption’ through our focus on the breast-feeding months and ‘costs to society’ through our comparative evaluation of breast-feeding mothers living in different social circumstances.

Objectives

-

– To explore the influence of social factors on patterns of alcohol use amongst breast-feeding mothers in the UK using an explorative quantitative research design.

-

– To quantify the influence of age and social factors (partner’s drinking status, educational attainment, age of child, household income, alcohol use during pregnancy) on patterns of alcohol use among breast-feeding mothers using the 2011 Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children(Reference Sommerville and Ong27).

Methods

Participants

We carried out a secondary data analysis using participant information drawn from data gathered as part of the 2011 Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children, a cross-sectional survey designed to capture the dietary habits of UK infants aged 4–18 months(Reference Sommerville and Ong27). The original sample composed of 4451 individuals. Of these, 3 % were excluded because they were fed artificially (aged 1 week or older) or weighed less than 2 kg. This left 4317 eligible to take part. Of these individuals, 62 % completed the survey in its entirety(Reference Sommerville and Ong27). The sample was weighted to ensure that it was representative of the UK population. We included data from all 2683 mothers with complete data who took part in the original survey and examined those who stated that they continued to drink alcohol whilst breast-feeding (n 227) according to their socio-demographic circumstances.

Statistical analyses

The binary outcome measure ‘Breastfeeding and drinking’ (Y/N) was derived from a positive response to questions posed to mothers about breast-feeding status (currently breast-feeding) and self-reported alcohol consumption (currently drinking alcohol).

The following variables identified as related to women’s alcohol were included (see Table 1): age, partner’s drinking status, educational attainment, age of child, household income, alcohol use during pregnancy(Reference Baker and Graham21). SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences)(28) was used to carry out the statistical analyses.

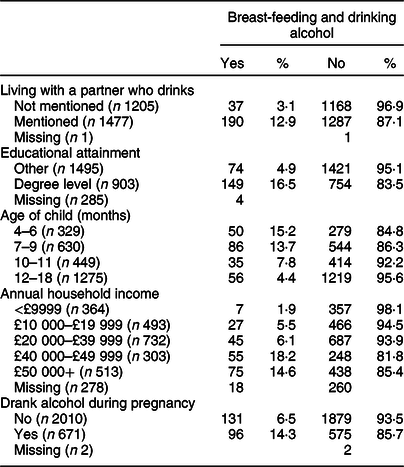

Table 1 Breast-feeding and drinking according to social circumstances

Table 2 Mutually adjusted model to illustrate significant predictors of breast-feeding and drinking*

* Adjusted for mothers’ age.

Descriptive statistics are reported for alcohol use among breast-feeding mothers according to social circumstances to ascertain whether they are significantly influential. Independent samples t test and χ 2 test for independence were performed on continuous and categorical variables, respectively. However, unlike OR, χ 2 tests do not provide information on the relationship between variables. Therefore, logistic regression that included mutually adjusted analyses was performed to assess the impact of the independent variables on the likelihood of mothers drinking whilst breast-feeding (dependant variable).

Results

Totally, 2683 mothers took part in the survey and n 227 reported that they continued to drink alcohol whilst breast-feeding. Table 1 provides a summary of the descriptive statistics that illustrate the proportion of mothers who drank alcohol whilst breast-feeding according to several social variables (education, drank whilst pregnant, living with a partner who drank, age of child and household income).

Additional analyses were carried out to determine whether differences in breast-feeding and alcohol consumption were significant for age and each of the social variables (education, drank whilst pregnant, living with a partner who drank, age of child and household income) (Table 2).

Age of mother

An independent samples t test was carried out to compare the age of mothers who drank alcohol whilst breast-feeding to those who did not drink alcohol whilst breast-feeding. There was a significant difference in age among breast-feeding mothers who drank alcohol (M 32·88, sd 4·75) and those who did not drink alcohol (M 30·09, sd 6·07; t(298·83) = −8·23, P = 0·000 (two-tailed)). This shows that older mothers are increasingly likely to drink alcohol whilst breast-feeding. However, the magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference −2·78, 95 % CI −3·45, −2·12) was very small (η 2 = 0·006)(Reference Cohen29).

Influence of partner

Women (12·9 %) who drank whilst breast-feeding reported living with a partner who drank in comparison with women (3·1 %) who drank whilst breast-feeding who did not report living with a partner who drank. A χ 2 test for independence (with Yates Continuity Correction) shows that living with a partner who drinks results in an increased likelihood of drinking whilst breast-feeding. However, the effect size was small(Reference Cohen29) χ 2(1, n 2682) = 80·89, P = 0·000, ϕ = 0.175.

Educational attainment

The proportion of women who breastfed and consumed alcohol was 16·5 % of women educated to degree level and 4·9 % of women not educated to degree level. A χ 2 test for independence (with Yates Continuity Correction) shows that higher educational attainment among mothers equals an increased likelihood of continuing to drink alcohol whilst breast-feeding. However, the effect size was very small(Reference Cohen29), χ 2(1, n 2398) = 87·69, P = 0·000, ϕ = −0.193.

Age of child

The proportion of mothers who drank alcohol and breastfed was 15·2, 13·7, 7·8 and 4·4 % when the child was aged 4–6, 7–9, 10–11 and 12–18 months, respectively. A χ 2 test for independence shows the younger the child, the more likely mothers were to consume alcohol whilst breast-feeding. However, the effect size was small(Reference Cohen29) χ 2(1, n 2683) = 68·70, P = 0·000, Cramer’s V = 0·160.

Household income

The proportion of mothers who drank alcohol and breastfed was 1·9, 5·5, 8, 11·7 and 14·6 % across the annual household income quintiles; £0–£9999, £10 000–£19 999, £20 000–£39 999, £40 000–£49 999 and £50 000+, respectively. A χ 2 test for independence shows that mothers living in high income households have a greater chance of drinking whilst breast-feeding. However, the effect size was small(Reference Cohen29) χ 2(1, n 2405) = 55·90, P = 0·000, Cramer’s V = 0·152.

Alcohol use during pregnancy

A χ 2 test for independence (with Yates Continuity Correction) shows that consumption of alcohol whilst pregnant results in an increased likelihood of consuming alcohol whilst breast-feeding. However, the effect size was very small(Reference Cohen29) χ 2(1, n 2681) = 88·39, P = 0·000, ϕ = −0·121.

Age and each of the social variables (education, drank whilst pregnant, living with a partner who drank, age of child and household income) were found to be significantly associated with the likelihood of mothers consuming alcohol whilst breast-feeding. To ensure all variables were contributing uniquely to the model, a Wald test was carried out. All correlation values were <0·1; therefore, no variables were excluded from the analyses. Therefore, using a model that included all six independent variables, logistic regression was performed to assess the impact of each of the variables whilst controlling for all the other variables.

The full model containing all predictors was statistically significant, χ 2(8, n 2173) = 208·55, P = 0·000, indicating that the model was able to distinguish between respondents who did and did not report drinking whilst breast-feeding.

The model as a whole explained between 9·2 % (Cox and Snell R 2) and 19·7 % (Nagelkerte R 2) of the variance in breast-feeding and alcohol use status and correctly classified 90·8 % of cases. Mothers’ age and four independent variables made a unique and significant contribution to the model (education, drank whilst pregnant, living with a partner who drank and age of child).

The strongest predictor of drinking whilst breast-feeding was education (OR 2·42, CI 1·67, 3·49, P = 0·000). This indicated that respondents who were educated to degree level or higher were 2·42 times as likely to consume alcohol whilst breast-feeding than those who were not educated to degree level. Age also predicted drinking whilst breast-feeding (OR 1·04, CI 1·01, 1·08, P = 0·014). For every increment in the mother’s age, the likelihood of drinking whilst breast-feeding was 1·04 times as likely. Drinking whilst pregnant predicted drinking whilst breast-feeding (OR 1·57, CI 1·14, 2·18, P = 0·006). This indicated that respondents who drank whilst pregnant were 1·57 times as likely to consume alcohol whilst breast-feeding than those who did not. Living with a partner who drank predicted drinking whilst breast-feeding (OR 2·24, CI 1·48, 3·39, P = 0·000). This indicated that respondents who lived with partners who drank were 2·24 times as likely to consume alcohol whilst breast-feeding than those who did not. The age of the child predicted drinking whilst breast-feeding (OR 0·22, CI 0·14, 0·34, P = 0·000). This indicated that respondents whose children were older than 12 months were 0·22 times as likely to consume alcohol whilst breast-feeding in comparison with those whose children were aged 4–6 months, controlling for other factors in the model.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that alcohol use whilst breast-feeding is influenced by age and several factors (education, drank whilst pregnant, living with a partner who drank, age of child and household income) mirroring previous research among mothers with pre-school-aged children(Reference Baker and Graham21). Our results suggest that mothers who drank during their pregnancy and who live with a partner who drinks alcohol are more likely to drink alcohol themselves whilst breast-feeding. In addition, we found that social advantage (higher educational attainment and household income) increased the likelihood of mothers continuing to drink alcohol whilst breast-feeding. These findings indicate that previous health behaviours, social and domestic factors are all influential concerning whether women chose to adhere to current guidelines that advocate abstinence whilst breast-feeding(23).

The effect of alcohol use whilst breast-feeding continues to be widely debated and clear evidence-based guidance for mothers is lacking(Reference Haastrup, Potteg and Damkier24). Furthermore, mothers are subject to conflicting advice at a time when they might already be struggling with the responsibility of parenthood(Reference Elek, Harris and Squire25). This uncertainty has likely led to the recommendation that breast-feeding mothers abstain from alcohol use for the duration they chose to breastfeed(23).

Evidence suggests that parenthood might prompt individuals to re-consider their own health-behaviour including alcohol use to align themselves with what is defined as socially acceptable(Reference Silva and Pugh30). Alcohol consumption is a part of UK culture(14,Reference Smith and Foxcroft31) , and previous studies have demonstrated how alcohol can be used to affirm membership of social groups(Reference Smith and Berger32) and portray mothers’ self-image separate to that of their children(Reference Baker22). However, research has found that becoming a parent brings about a shift in what is considered socially acceptable(Reference Hartrick33,Reference Choi, Henshaw and Baker34) . Breast-feeding has been found to conform to the ‘good’ mother ideology(Reference Lee35). Therefore, mothers might choose to discontinue breast-feeding rather than risk being considered deviant(Reference Lee35). As previously mentioned, our results suggest that mothers who are socially advantaged are more likely to continue to consume alcohol whilst breast-feeding. This might be related to the fact that they are less likely to suffer the stigmatisation and marginalisation experienced by socially deprived members of society as a result of their health behaviour(Reference Room36).

Whilst advice to abstain is undoubtedly given with the best of intentions, one might argue that a less stringent approach whereby a moderate amount of alcohol consumption is advocated perhaps with additional advice around the timing of feeds might lead to increased breast-feeding rates and mothers continuing to breastfeed for longer. A positive example of describing different options for breast-feeding and alcohol consumption is the National Health Service ‘breastfeeding and drinking alcohol’ website which in detail, describes different options for women when breast-feeding, what alcohol units are, how often occasional drinking should be, what not to do when consuming alcohol, when to see your doctor if you drink higher than a recommended ‘safe amount’. This information might be better utilised and understood if it was described in detail during midwives/or health visitor visits(37). This is not to ignore the potential for harm posed by breast-feeding mothers who consume excessive amounts of alcohol, but this needs to be balanced with the majority for whom moderate alcohol consumption is the norm.

Both breast-feeding and alcohol consumption have the potential to positively or negatively influence health outcomes. In our study, breast-feeding and continued alcohol use were positively associated with several social factors such as mothers’ age, mothers with partners who drank alcohol, higher educational attainment, higher household income and consumption of alcohol during pregnancy. Breast-feeding and continued alcohol use were negatively associated with infant age. However, there are a number of limitations associated with the study. For example, alcohol consumption was self-reported and mothers might not have given an accurate portrayal of their intake. In addition, the cross-sectional design does not analyse behaviour over time.

Further prospective exploration as to why these patterns exist is necessary to determine what level of influence alcohol consumption might have on the continuation of breast-feeding and viceversa across different social groups. This will enable policy makers to develop targeted interventions that support longer-term breast-feeding. In the meantime, robust evidence-based guidelines around alcohol consumption and breast-feeding that are less restrictive might permit mothers to breastfeed for longer.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all the mothers who participated in the original study and the Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children (2011) for allowing access to the data. Financial support: The current research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: S.B. designed the study, carried out the analyses and prepared the manuscript. M.C. reviewed the statistical analyses and contributed to writing the article. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by Leeds Beckett University Ethics Committee. Written (or verbal) informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.