INTRODUCTION

Long-term archives of pre-written era tsunami events are invaluable for understanding the potential sources, magnitude, inundation characteristics, and frequency of large to great tsunamis. The most common form of scientific evidence to identify pre-written tsunami events (hereafter palaeotsunamis) is based on stratigraphic studies using sedimentary records supported by micro-palaeontology, geochemistry, geomorphology, palynology, limnology, archaeology and geochronology (Atwater, Reference Atwater1987; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Long and Smith1988; Minoura and Nakaya, Reference Minoura and Nakaya1991; Atwater and Moore, Reference Atwater and Moore1992; Clague and Bobrowsky, Reference Clague and Bobrowsky1994; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Bryan and Ludwig1994; Hemphill-Haley, Reference Hemphill-Haley1996; Goff and Chagué-Goff, Reference Goff and Chague- Goff1999; Dawson and Shi, Reference Dawson and Shi2000; Chagué-Goff et al., Reference Chagué-Goff, Dawson, Goff, Zachariasen, Berryman, Garnett, Waldron and Mildenhall2002, Reference Chagué-Goff, Goff, Nichol, Dudley, Zawadzki, Bennett and Mooney2012; Nichol et al., Reference Nichol, Lian and Carter2003, Reference Nichol, Goff, Devoy, Chagué-Goff, Hayward and James2007; Pinegina et al., Reference Pinegina, Bourgeois, Bazanova, Melekestsev and Braitseva2003; Cisternas et al., Reference Cisternas, Atwater, Torrejon, Sawai, Machuca, Lagos and Eipert2005; Morton et al., Reference Morton, Gelfenbaum and Jaffe2007; Nanayama et al., Reference Nanayama, Furukawa, Shigeno, Makino, Soeda and Igarashi2007; Jankaew et al., Reference Jankaew, Atwater, Sawai, Choowong, Charoentitirat, Martin and Prendergast2008; Sawai et al., Reference Sawai, Jankaew, Martin, Prendergast, Choowong and Charoentitirat2009; De Martini et al., Reference De Martini, Barbano, Smedile, Gerardi, Pantosti, Del Carlo and Pirrotta2010; Goff et al., Reference Goff, Nichol, Chagué-Goff, Horrocks, McFadgen and Cisternas2010, Reference Goff, Goto, Chagué, Watanabe, Gadd and King2018; Goto et al., Reference Goto, Kawana and Imamura2010; Ramirez-Herrera et al., Reference Ramírez-Herrera, Lagos, Hutchinson, Kostoglodov, Machain, Caballero and Goguitchaichvili2012; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Hayward, Cochran, Wallace, Power and Sabaa2015; King et al., Reference King, Goff, Chagué-Goff, McFadgen, Jacobson, Gadd and Horrocks2017; among many others). These studies have greatly contributed to scientific knowledge about tsunami hazard and, in combination with detailed studies of modern tsunami deposits (e.g., Morton et al., Reference Morton, Gelfenbaum and Jaffe2007; Sawai et al., Reference Sawai, Jankaew, Martin, Prendergast, Choowong and Charoentitirat2009; Chagué-Goff et al., Reference Chagué-Goff, Goff, Wong and Cisternas2015), have expanded the use of proxies to identify palaeotsunamis. However, few scientific studies about tsunami hazard (and history) acknowledge, much less engage with the value and potential contributions from Indigenous histories of the environment.

There are exceptions, however, that share the basic premise that productive scholarship about environmental history can benefit from epistemological and empirical differences in knowledge, practice and belief (Vitaliano, Reference Vitaliano1973; Heaton and Snavely, Reference Heaton and Snavely1985; Hutchinson and McMillan, Reference Hutchinson and McMillian1997; Nunn and Pastorizo, Reference Nunn, Pastorizo, Piccardi and Masse2007; King and Goff, Reference King and Goff2010; King et al., Reference King, Goff, Chagué-Goff, McFadgen, Jacobson, Gadd and Horrocks2017; Nunn, Reference Nunn2018). Vitaliano (Reference Vitaliano1973) considered the scientific benefits of Indigenous expertise and information about tectonic and geologic hazards. Detailing examples of coastal deluge attributed to tsunamis (and their likely sources) in classical and pre-colonial history, she argued that insights from Indigenous narratives provide invaluable lessons about extreme environmental disturbances in the pre-written past. Scholars from diverse disciplines have since explored pre-colonial coseismic histories from the Pacific Northwest coast of North America (Heaton and Snavely, Reference Heaton and Snavely1985; Clague, Reference Clague1995; Hutchinson and McMillan, Reference Hutchinson and McMillian1997; McMillan and Hutchinson, Reference McMillan and Hutchinson2002; Ludwin et al., Reference Ludwin, Dennis, Carver, McMillan, Losey, Clague, Jonientz-Trisler, Bowechop, Wray and James2005; Ludwin and Smits, Reference Ludwin, Smits, Piccardi and Masse2007; Thrush and Ludwin, Reference Thrush and Ludwin2007) to islands across the Pacific Ocean (Nunn, Reference Nunn2001; Lum-Ho and Lum-Ho, Reference Lum-Ho and Lum-Ho2005; Nunn and Pastorizo, Reference Nunn, Pastorizo, Piccardi and Masse2007; King et al., Reference King, Goff and Skipper2007, Reference King, Shaw, Meihana and Goff2018; McFadgen, Reference McFadgen2007; Goff et al., Reference Goff, Charley, Haruel and Bonté-Grapentin2008; King and Goff, Reference King and Goff2010). Heaton and Snavely (Reference Heaton and Snavely1985) reviewed the early ethnographic writings of James Swan, and concluded that many accounts of great sea-level disturbances within Native American and First Nations oral histories are consistent with tsunami inundation processes. McMillan and Hutchinson (Reference McMillan and Hutchinson2002) thereafter examined traditions from the northern Washington and southern British Columbia coasts that referred to recurring Holocene seismic activity and tsunami impacts. Importantly, these authors argued that Indigenous oral histories provide invaluable independent sources of information that can inform as well as challenge data from geological and archaeological research, such as the case for region-wide megathrust earthquakes. However, Thrush and Ludwin (Reference Thrush and Ludwin2007) reflected how the geological sciences privilege and favour the production of certain kinds of knowledge. Subsequently, these authors concluded that realising learning opportunities through cross-cultural exchange requires confronting questions about the limitations of geological enquiry, its relationship with colonialism, and its treatment of intellectual and cultural property matters, as well as the complex relationships between researchers and the researched.

In Aotearoa-New Zealand (Aotearoa-NZ), Māori histories that reference ancestral experience with catastrophic saltwater inundations prior to the arrival of the first Europeans in the late eighteenth century have become the subject of recent learning efforts. King et al. (Reference King, Goff and Skipper2007) reviewed an assortment of written records and stories that described the impacts from great waves caused by storms, incantations, and taniwha (entities inhabiting rivers, swamps, lakes, and the ocean as well as trees, stones, and the subterranean earth) and argued that some of these stories memorialise historical events. During the same period, McFadgen (Reference McFadgen2007) collated extensive archaeological, geological, and ethnographic evidence to infer that the fifteenth century in Aotearoa-NZ was marked by frequent earthquakes and tsunamis. King and Goff (Reference King and Goff2010) thereafter mapped selected Māori oral histories and geoarchaeological evidence, and discussed the potential value and benefits of this “new” information for understanding tsunami hazard and risk in Aotearoa-NZ. These authors cautioned, however, that without first-hand experience of the underpinning knowledge-practice-belief “complex” of Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge), from whence the stories derive, there is the potential to turn such stories into things that they are not. Accordingly, King and Goff (Reference King and Goff2010) concluded the need for cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural approaches to research that respect the rights of Māori to tell our/their own histories, in a greater project of acceptance of “other” ways of knowing science.

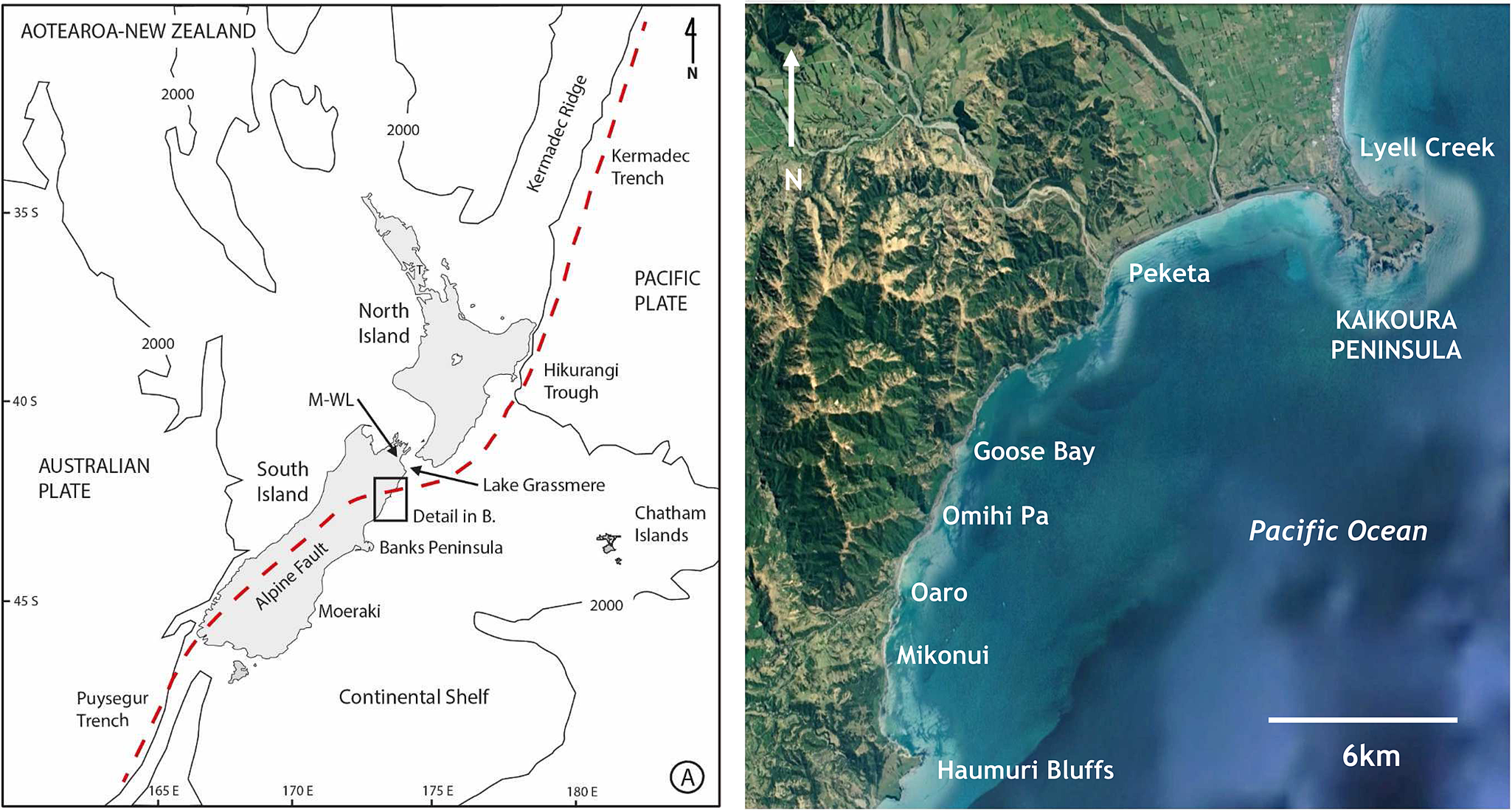

The research described in this paper adds to the collective developments outlined above by working alongside 22 members of the Māori kin-group Ngāti KuriFootnote 1 to deliberate the nature, function, and meaning of two ethnographic records that potentially reference Māori experiences with past tsunami(s) in the KaikōuraFootnote 2 District of Aotearoa-NZ, and to compare these with active oral histories (Fig. 1a). The intent of this work is to appreciate the manner in which Ngāti Kuri interpret their past and the present, and to add to the lack of substantive written data about tsunami inundation along the Kaikōura coast using understandings stored within active oral histories. The paper begins by considering the connections as well as the distinctions between Māori oral history and tradition. It then reviews some of the issues related to the authenticity (and bias) of Māori oral histories and tradition (including written records based on oral transmissions), and how these challenges can limit their meaning, particularly when removed from cultural contexts. This is necessarily followed by acknowledgement of related developments in political, epistemological, and methodological scholarship. Next, the paper outlines the research framing and methods of analysis before presenting synopses of the two ethnographic narratives. Lastly, it summarises and discusses the recollections and reflections of kin-group members on the key elements and storytelling devices in the two narrative, allowing the diversities of meaning and history to be heard. Māori language translations are repeated in each new section to assist the reader.

Figure 1: (color online) (A) Aotearoa-New Zealand's tectonic location in the South Pacific showing the Australian-Pacific plate boundary as a dashed red line. The submerged continental shelf boundary is loosely defined by the 2000 m isobaths (adapted from Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Lewis and Davey1988)). (B) The Kaikōura coast and surrounding locations mentioned in active oral histories and ethnographical records (Photo source: Land Information New Zealand, 2004/05).

MĀORI ORAL HISTORIES, TRADITIONS, AND CROSS-CULTURAL ENCOUNTERS

There are deep connections, as well as distinctions, between Māori oral history and tradition. Definitions of oral history typically refer to narrators or storytellers recounting first-hand experience within their lifetimes, while oral tradition is more commonly explained as the transmission of narratives, accounts and messages by subsequent generations (Vansina, Reference Vansina1985). Such framings of oral narratives, however, do not always account for the imprecise boundaries between these terms. Nor are they able to capture the inseparability between the recent and distant past which is often central to Māori narratives (Tau, Reference Tau2003; Taonui, Reference Taonui2005; Mahuika, Reference Mahuika2019). Tau (Reference Tau2003) offered an interpretative scheme for classifying Māori oral traditions and histories based upon symbolic (also referred to as mythic) and historical elements, and the changes that have occurred through external influences and internal change. He proposed four temporal realms of oral tradition to differentiate weightings between history and the distant past. These realms are: historical written sources, details from oral traditions, the mytho-history realm of ancient genealogy, and the realm of “myth” which connects humankind to the gods. While this scheme does not embody a traditional Māori view of the recent and/or distant past, it nonetheless emphasises that oral narratives and writings can be more than historical recollections. Building upon this work, Taonui (Reference Taonui2005) grouped oral traditions into six categories: creation, demigod, migratory, tribal, natural lore, and customary lore. The first four are similar to Tau (Reference Tau2003) but the inclusion of the dynamics of natural lore and customary lore, and how they span the continuum of oral traditions from creation to the present day, are distinct. Natural lore offers explanations for the origins of natural phenomena and human-nature relationships, while the purpose of customary lore is to impart moral codes where knowledge, practice and belief are projected back into the past (Taonui, Reference Taonui2005). This model enables deeper analysis of the meaning and role that different traditions played in defining society's relationship with the land and the moral codes of social behaviour. Further, it is helpful as it recognises the connectedness (or rather the blurred lines that exist) between the recent and distant past, as well as the incorporation of both historic and symbolic elements into Māori oral traditions and histories.

A number of scholars (Simmons, Reference Simmons1976; Binney, Reference Binney1987; Soutar, Reference Soutar1996; Williams, Reference Williams2000; Tau, Reference Tau2003; Taonui, Reference Taonui2005) have identified criteria for assessing the reliability (and authenticity) of Māori oral histories and traditions (based on written records). The criteria include examining the role of the informant and the recorder, the potential for personal and cultural bias, as well as the motives (in the case of written records) of the publisher. These scholars also emphasise the social, ideological, and political pressures of the period in which narratives are told and recorded, including the influence of ideas external to Māori society that have resulted in changes to the content of some narrative forms (Mikaere, Reference Mikaere1995; Taonui, Reference Taonui2005). Recognition that the narrators (and writers) of history, regardless of where they come from, are neither objective nor neutral (Binney, Reference Binney1987) underscores the need for careful scholarship and cross-checks to help establish the veracity of specific histories and traditions (Binney, Reference Binney1987; Soutar, Reference Soutar1996; Williams, Reference Williams2000; King and Goff, Reference King and Goff2010). Further, collaborative storytelling methods that involve working alongside kin-group members who continue to actively participate in the transmission of such narratives have demonstrated the critical role such grounded histories can make to scholarship (King et al., Reference King, Shaw, Meihana and Goff2018). Notwithstanding these points, we remain mindful that Māori oral histories and traditions provide more than alternative sources of information or even alternative perspectives (Binney, Reference Binney1987; Smith, Reference Smith1999; Mead, Reference Mead2003; Hakopa, Reference Hakopa2019). Rather, they have their own purposes, which may sometimes complement the academy of science to establish meaning for discrete and repeated events through time (King et al., Reference King, Shaw, Meihana and Goff2018).

Regardless of the value of the scholarship outlined above, many Māori have had (and continue to have) an uncomfortable relationship with scientific enquiry (and related ethnography), particularly by non-Māori. One reason is that written accounts about Māori by non-Māori often reflect different priorities and perceptions of the world (Salmond, Reference Salmond and Overling1985; Binney, Reference Binney1987; Mikaere, Reference Mikaere1995; Smith, Reference Smith1999). Bishop and Glynn (Reference Bishop and Glynn1999) also argue that such writings sometimes fail to understand and accept the complex nature of Māori kin-group systems, histories, and knowledge. The issue is not that these writings are simply unreliable, but rather that they reflect ongoing colonial and post-colonial assumptions that scientific epistemologies are the standard by which all other forms of knowledge are judged (Salmond, Reference Salmond and Overling1985).

Further, a history of extractive research practice has resulted in a culture of non-Māori research which has not acknowledged Māori knowledge(s) or its holders who often have no moral or legal rights to decide how knowledge will be represented or used within the wider world (Smith, Reference Smith1999). Many Māori and other Indigenous/First Peoples have therefore begun to “reverse the pen” by leading research and critiquing how we/they are represented. Informed by decolonising and counter-colonial research theory, methodologies, and methods, their efforts seek to reframe and transform the way research and knowledge are produced, including, among other objectives, to protect and reimagine productive, meaningful, and rewarding lives (Smith, Reference Smith1999; Mead, Reference Mead2003; Durie, Reference Durie2005; Kovach, Reference Kovach2009; Cram et al., Reference Cram, Chilisa, Mertens, Mertens, Cram and Chilisa2013). A challenge ahead for the geological sciences is to respect the authority of Māori and other Indigenous/First Peoples to tell and share our/their own stories, while simultaneously encouraging plural knowledge development (Mead, Reference Mead2003; Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Reference Howitt, Suchet-Pearson, Anderson, Domosh, Pile and Thrift2003; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Herman and Dobbs2006; Thrush and Ludwin, Reference Thrush and Ludwin2007; Roberts, Reference Roberts2013; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Howitt, Cajete, Berkes, Louis and Kliskey2016; King et al., Reference King, Shaw, Meihana and Goff2018; Meihana and Bradley, Reference Meihana and Bradley2018).

RESEARCH FRAMING

Methodological approaches

This research followed an inductive-based approach informed by “collaborative storytelling” (Bishop, Reference Bishop1999; Lee, Reference Lee2009; King et al., Reference King, Shaw, Meihana and Goff2018) to help deliberate the nature, function, and meaning of two ethnographic records by comparing these records with active oral histories. Supporting a wider call to decolonise research methodologies (Smith, Reference Smith1999; Kovach, Reference Kovach2009), while seeking inclusivity of “different,” and sometimes supressed knowledges (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Reference Howitt, Suchet-Pearson, Anderson, Domosh, Pile and Thrift2003; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Herman and Dobbs2006; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Howitt, Cajete, Berkes, Louis and Kliskey2016), all phases of the research observed Kaupapa Māori research principles expressed through enduring cultural rules, norms, and procedures (Smith, Reference Smith, Smith and Hohepa1990; Te Awekotuku, Reference Te Awekotuku1991; Smith, Reference Smith1999). Implicit within this approach was an active commitment to the rights and interests of the participating kin-group members from Ngāti Kuri. All kin-group respondents were assured of their right to maintain authority over their contributions by reviewing, editing, and approving the “new” narratives produced through this work. The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research provided human research ethics approval (HREC2018-015).

Methods, analysis, and interpretation

The research methods included the use of semi-directed individual and paired interviews with 22 kin-group members to discuss the potential inclusion of tsunami narratives within two ethnographic records published in English (Carrington, Reference Carrington1934; Elvy, Reference Elvy1949). Interviewees were identified through extended familial networks. Each interview lasted between 0.5 and 2 hours and was attended by at least one research facilitator. All interviews occurred at Takahanga Marae (sacrosanct buildings and ground belonging to Ngāti Kuri) and/or the private homes of kin-group members and were electronically recorded. All interviews began with an exchange of formal acknowledgments in the Māori language. Thereafter, interviews were conducted predominantly in the English language, depending on the preference of the kin-group member. Analysis of interview material was inductive and involved (1) “content analysis,” whereby ideas or words were identified along with the frequency of their use, (2) “thematic analysis,” whereby principal elements emerging from the data were examined and sorted, and (3) cross-checking the integrity of emergent ideas and interpretations through follow-up discussions with key informants, with adjustments made where necessary (King et al., Reference King, Shaw, Meihana and Goff2018). Central to these analyses was an emphasis on respondent views about the narrative (rather than the meaning the researchers brought to the research). Secondary sources of information provided supplemental support.

ETHNOGRAPHIC RECORDS

Taniwha at Oaro, Kaikōura

The following reproduction of the story of the “Taniwha of Oaro” comes from Carrington's (Reference Carrington1934: 193–194) original English language version (Fig. 1b). In the preface, Carrington (Reference Carrington1934) acknowledged Hariata Whakatau Beaton-MorellFootnote 3, a respected elder of Ngāti Kuri, as the principal source of the information contained in his collection.

There is also a well-known and authenticated taniwha connected with the Oaro. It was a sort of serpent that lived in a little lagoon just at the northern end of the present traffic bridge. The lagoon has only recently been filled by a slip, and its position is well-known to the older inhabitants of the valley (1933). The taniwha's method of movement is described as being like that of a caterpillar. It would arch its back high and then spring forward from its tail. When it moved its tail forward, it scooped the water in front of itself in a wave. As a Maori said: “nobody believes it, but it's quite true.” Two young girls searching for Tarata [Lemonwood], the gum of which they mixed with oil to make a sweet scent, fell to eating konini [Fuchia] berries and wandered from the pa [settlement] at Omihi as far as the lagoon at Oaro. They admired the waters of the lagoon which were blue like the sea, though half a mile or more from it, climbed the nearby konini tree the better to reach the berries which were ripe. So luscious was the fruit that they failed to notice the waters of the lagoon rising until the tree was surrounded, and the Taniwha was arching his back for the final spring. Terror-struck, the girls did not know what to do. One girl jumped and managed to reach safety, but the other jumped too late, and the dreaded jaws snapped her up, and she was swallowed whole. The girl who escaped having seen the dreadful fate of her companion did not stop running until she reached Omihi, where she told her relations the story. They had known the dangers of that track along the banks of the Oaro, but not thinking the girls would wander so far had not troubled to warn them or provide an escort. Fortunately, one of the tōhunga [expert in traditional lore, person skilled in specific activity, healer] of the pa was an urukehu [olden people who were larger in stature that lived in the area], who were particularly powerful where tanìwha were concerned. Led by the urukehu, the warriors went to the lagoon. There the proper ceremonies were performed and the karakia [prayer, incantations] sung. Unable to resist, the Taniwha appeared from the water, and disgorged the body of the child, dead, but quite whole. The men at once set upon it and killed it with their spears.

This story has been reproduced, sometimes in varying form, by Sherrard (Reference Sherrard1966), Beattie (Reference Beattie and Anderson1994), McFadgen (Reference McFadgen2007), and Tau and Anderson (Reference Tau and Anderson2008). However, McFadgen (Reference McFadgen2007) questioned whether the story might represent a hazard narrative about one (or multiple) tsunami inundations prior to the arrival of the first Europeans in the late eighteenth century. Ngāti Kuri kin-group members views and reflections about this narrative are presented in the “Storytelling Through Whakapapa” section below.

Taniwha at Lyell Creek, Kaikōura

The following reproduction of the story of the “Taniwha at Lyell Creek” comes from the original English language version produced by Elvy (Reference Elvy1949: 65–66; Fig. 1b). According to Sherrard (Reference Sherrard1966), the story was imparted by one of the elders from the Poharama family, and it is preserved in other parts of Aotearoa-NZ, albeit “localised” in the district of the kin-group recounting it. No further information is provided about the source of this story.

Ngāti Māmoe had a legend of a taniwha that lived in the lagoon at the mouth of Lyell stream. Its name was Matamata. I have collected the story of this taniwha of Lyell Creek from a descendant of Maru the Ngāi -Tahu hero, who figures in the following story. It appears that about 250 years or more ago, when the Ngāti-Māmoe and the Ngāi Tahu battled for the possession of the Kaikōura Peninsula, the former tribe had a pet taniwha which they placed at the mouth of the Lyell stream. The spot is (or was) known as Wai te Matamata. In those days the limestone bluffs came right down to the river and one had to walk along a narrow track at the river edge. From the description given me, this taniwha was a ‘nasty bit of work’. He had a long neck and a scaly body. His job was to keep the Ngāi Tahu from travelling past the river mouth, towards the Peninsula. He did this most effectively by ejecting a noxious fluid which stupefied the intruders, who were then devoured by him. After losing a number of his tribe by the attacks of this monster, the chief, Maru, decided that something must be done about it. He had a strong noose prepared, and when the monster was asleep he and some of his bravest warriors hid themselves in the flax and raupo along the stream near his lair. He then arranged for some fleet-footed youths to entice the monster out. They did this by shouting insults at it; and while it was peering round to discover the offenders, Maru threw the noose over its head, and his companions, hauling on the attached rope, soon had it choking and helpless. Maru then approached the monster and slew it with his magic axe. When they opened up the taniwha they found in its stomach the clothes, ornaments and weapons belonging to the various victims it had devoured. Lineal descendants of Maru are still living in the Kaikōura district.

Sherrard (Reference Sherrard1966), Orbell (Reference Orbell1985), Reed (Reference Reed2004), and Walters et al. (Reference Walters, Barnes and Goff2006) have all reproduced this story, sometimes in varying forms. However, it was Walters et al. (Reference Walters, Barnes and Goff2006) who surmised the story may have connections with the coseismic history of the Kaikōura District prior to the arrival of the first Europeans in the late eighteenth century. Ngāti Kuri kin-group members views and reflections about this narrative are presented in the next section.

STORYTELLING THROUGH WHAKAPAPAFootnote 4

Knowledge of the story from Oaro

The written version of the Oaro taniwha narrative, as reproduced above, was known by a select few of the respondents from Ngāti Kuri. For example: “I am aware of this story. When my great grandmother was living down there she would tell the kids not to swim in that part of the lagoon because the taniwha lives there. And the kids were always told that, and so they never swam in that particular spot because that is where the taniwha took the girl away” (respondent 9). Other kin-group respondents had different memories of the story. For instance, “I have heard this story before although I have not read it in print. I remember the korero [talk] around there being a taniwha, and there was one particular part of the lagoon that you just didn't swim because of the tail of the taniwha” (respondent 1), and “I was told about the two girls down there. We were always told not to go there because of the girls…occasionally down past Mikonui [bay to the south of Oaro] you would hear her screaming” (respondent 11). In contrast, a number of respondents were altogether unfamiliar with the narrative: “I was taken away when I was young. I never heard those stories. And by the time I got back the old people had gone” (respondent 15). These commentaries demonstrate not only varying knowledge among different kin-group members but also that it is not possible to explain these variations by simply considering which side of the Peninsula that kin-group members were from.

All respondents knew of Hariata Whakatau Beaton-Morell and some were direct descendants. Many also shared that Hariata was most likely instructed by her uncle Tapiha Te Wanikau (a well-known expert in traditional lore from Kaikōura) and that it was common knowledge that Hariata was the principal source for Carrington's (Reference Carrington1934) written manuscripts. Almost all respondents declared they had no reason to distrust Carrington's accounts because Hariata was such an authoritative source. However, respondents 18 and 22 expressed caution about interpreting Carrington's recordings, citing the potential for loss of meaning when Māori narratives are retold in English. While the authors of this paper concur with these cautions, we are not aware of a written Māori version of the Oaro narrative, and this emphasises the importance of the approach taken in this study to engage directly with kin-group members who hold genealogical links to the story and Hariata Whakatau Beaton-Morell. These points will be considered further in the “Discussion and Future Research” section below.

Key elements and function(s) of the Oaro narrative

In discussing the key elements and function(s) of the Oaro narrative kin-group, respondents familiar with the story commonly affirmed the existence of the taniwha and thereafter offered reflections on its significance in the death of the young girl at the lagoon. For example, “The way the story reads is that the water rises up and takes her [the girl] and I think that is the taniwha. And the way it talks about arching its back is the water, its wave motion, the water that took her” (respondent 5), and “For me, the work I have done on the manuscripts is to start thinking of the picture that people are putting out there. Those are waves” (respondent 20). Next, the type of waves recounted in the story was also discussed. For example, “I believe this story refers to a tsunami, just the quickness [of] how it rises, and then it drops and the devastation that is left. And the taniwha was killed …. If it was a flash flood coming down the river, the river would probably still have been high, but a tsunami comes in boom and then it goes out and drops straight down. Sometimes you can get several [waves] but you could just get one, one big wave, and that is what I suspect the story talks about” (respondent 5), and “I have seen it. There was a massive storm, and someone had a caravan parked on the river side of the bridge … we were standing there, and it was probably about 7 or 8 o'clock at night and this massive wave came through. It went underneath the bridge, and honestly it was just like a wheke [octopus], it went around, and it grabbed the caravan … and it pulled the caravan underneath the bridge, smashed [it], and then another wave came in again and grabbed the caravan and dragged [it] away” (respondent 4). Such differences in interpretation and experience were common. This emphasises that storytelling is not only specific to communities, families, and individuals, but is also open to personal interpretation. According to respondent 9, the distinction between tsunami and storm surge might even be artificial, given the story was composed within a time and culture that viewed the world differently from the way we do at present.

Such deliberations led on to considering the intention of Hariata and other kin-group storytellers in transmitting such narratives as well as the role of taniwha in explaining and characterising extreme events and phenomena. Examples of these reflections include: “For years we didn't know why he [grandad] would tell us these stories about different tohu [signs, indicators]. We were thinking this was our time with grandad, and it was the same stories over and over again. As an adult, one realises that what he was handing you was whakapapa [ancestral lineage, genealogy] and teaching us about what to look for in the environment … We live in a hazardous place and that is the taniwha” (respondent 1), and “Back in those days the way unusual events were explained was through taniwha” (respondent 8). While it is uncertain whether Hariata was communicating an event that occurred in her lifetime, or earlier, the statements above highlight that a key function of the story is to transmit warnings about the hazard and ongoing risk in and around the lagoon. Agreement was not unanimous, however, on this point. Respondent 22 questioned the authenticity of the story and whether it was merely a common narrative for entertainment. While it is difficult to reconcile these views, the authors consider that such scepticism centres more around concerns about turning stories into things that they are not.

Several respondents reflected further on the relationship between taniwha and the transgression of rules associated with tapu (sacrosanct, forbidden, and/or inviolable). For example, “We have to get out of our western mind of thinking about goblins and monsters. Taniwha are kaitiaki [beings that act as carers, guardians, protectors and conservers], they are there to protect us. A lot of tōhunga [expert in traditional lore, person skilled in specific activity, healer] had taniwha to do their bidding. They were fed with karakia [prayer, incantation], and they had to be acknowledged in certain ways. So, I think taniwha are about modifying our behaviour and conducting ourselves in a certain way to ensure we are safe” (respondent 18), and “One of the things I think about is that tikanga [behaviour, correct procedure, lore] was not followed. For me a lot of our stories are about imbalance in the world” (respondent 19). Such reflections emphasise that rather than simply representing an environmental hazard, the taniwha also reminds the living about natural and customary lore, the boundaries between the known and the unknown, and the interconnectedness between humans and nature.

The significance of the killing of the taniwha in the story was also considered. Respondents commonly agreed that slaying the taniwha did not mean that it no longer existed but that the risk associated with the hazard at the lagoon had been removed for the time being. For example, “I don't believe that part [about the killing of the taniwha]. It re-emerges given the conditions” (respondent 6) and “My personal take on it is that in pūrākau [narratives surrounding ancestral deeds and teachings] there are several elements … When you have the killing of the taniwha that is probably speaking to the mana [dignity, authority, control, prestige, power] of [hu]man[s], and that we can overcome adversity … certain events and tragedies and trauma. It would be easy to look at it from a western viewpoint and say that the taniwha is dead and it no longer exists but, in a Māori sense, the moon wanes, it dies and rises again. You cut down a cabbage tree and it rises again” (respondent 18). Added to these interpretations, several respondents associated the slaying of the taniwha and “the disgorging of the body completely whole” to the specific aftermath of a tsunami and/or extreme flood when the waters recede, and the impacts of the event become evident. For instance, “I wonder about that, whether the taniwha, if it was slayed meant it [the water in the lagoon] dropped down, back to normal” (respondent 4), and “they killed the taniwha and cut it open and then they found all kinds of other things and that could have been one wave that caught a lot of things. The taniwha could have taken that girl and after it [the water] receded it could have left that devastation” (respondent 5).

In contrast, three respondents held divergent views about the killing of the taniwha. They viewed this part of the storyline as a “template” used in other stories and thereby questioned the reliability of the narrative, including whether the story might be borrowed from elsewhere. For example, “there are a number of iconic stories here in the South Island and there are a number of us that doubt the accuracy of those stories. That's not to say they are totally wrong but we [must be cautious]” (respondent 21), and “all pre-literate cultures have elements like that in them…and when you read their stories and you hear them telling them, you say, I have been here before” (respondent 22) and, “maybe it's one of these situations where the tradition came from one place, but it is used to explain an event in another location“ (respondent 8). While it is beyond the scope of this study to examine in more depth questions surrounding the potential translocation of the story, such comments underscore the need for careful consideration of stories found within ethnographic accounts.

Finally, beyond the direct naming of places such as Oaro and Omihi Pā, most respondents were familiar with other contextual details provided in the story such as the konini (Fuchia) berry. For example, “The konini berry is what we know. It was sought after and has a sweet grapey-plum taste…They were a treat because of the sweetness. I still eat them today. The thought of two girls picking the konini berries just validates the story [for me]” (respondent 5). Similarly, several respondents commented upon the reference to “urukehu” [the olden people who lived in the area] in the story. For instance, “we have a lot of kōrero here about the urukehu people. They were part of our people the urukehu…especially at Oaro” (respondent 11). Respondents 8 and 9 explained that such elements are deliberate to help ensure the stories are not forgotten and to affirm Ngāti Kuri connections to the story and place. In the words of respondent 8, “You want the lesson or notion to settle within somebody, and you also want it being told in a way that it maintains its mana [dignity, authority, control, prestige, power]…Places and people and taniwha become the mnemonics for the story.”

Analogue stories from Kaikōura

Further discussions and deliberations led several respondents from Ngāti Kuri to share at least two additional narratives from Kaikōura that include references to catastrophic waves and potential tectonic disturbance. The first story was described by respondents 1 and 5, both of whom hold close ties to Oaro. For instance: “There was a story that used to be told about a wahine [woman] who had her baby in Oaro and the baby fell into the ocean. The mother went running to the tōhunga [expert in traditional lore, person skilled in specific activity, healer] to say that her baby had drowned and was there something that he could do. He gave her a karakia [prayer, incantation] and he said to her to recite the karakia and whatever you do don't stop. So, she recited the karakia and a dolphin came up with the baby on its back. Anyway, the wahine got so excited [she stopped the karakia] that the dolphin and baby were turned to stone. There are a number of lessons I take from that… I have related that story to what happened to us in the earthquake [Kaikōura, November 2016] in terms of the rapid uplift. As the dolphin rose so did the land come up and the water drew out. So that's a story that I think has relevance to this place. And also of course, my grandfather was saying never to stop when you are doing a karakia” (respondent 1). While there are differences about whether a child or baby was swallowed by the sea, the dolphin and child were petrified standing above the water and this aspect of the story was viewed as symbolising earthquake uplift. No written version of this story has thus far been located.

Three kin-group members also relayed the story of the Niho-manga (shark tooth) and the occurrence of catastrophic waves at Peketa on the southern side of the Kaikōura Peninsula (Fig. 1b). In the words of respondent 2: “Our Mum talked about a battle between two kaumatua [elders] both of [Ngāti] Kuri and one stood on this Peninsula and the other one stood over at Peketa, or around that area, and they literally had a battle, but it was a magical battle. She didn't mention the names of the kaumatua…the battle was won by throwing the waves. Mum believes that the one up here on Ngā Niho Pā [an historical settlement situated high on the Kaikōura Peninsula] won it. He ended up throwing the niho [tooth] of the shark which caused the wave to wipe that tōhunga [expert in traditional lore, person skilled in specific activity, healer] out. They were both tōhunga. Standing on the Peninsula you can definitely visualise the story. Mum would tell us about these stories when we were collecting kai [food], and also when we had visitors going for walks.” Respondents 9 and 13 independently shared the story in similar ways, acknowledging the great battle involving catastrophic waves.

Knowledge of the story from Lyell Creek

Kin-group respondents were not aware of the written version of the story from Lyell Creek. However, some did recognise aspects of the story, such as the name of the taniwha, Matamata, the ancestral “hero,” Maru, responsible for its killing, and the description of physical places such as the limestone bluffs. Regardless of these recognitions, Matamata was not considered to have a “long neck and a scaly body” (Elvy, 1949), and nor was there any knowledge of Matamata residing at the mouth of the Lyell stream. Rather, respondents more commonly acknowledged “Matamata was the whale taniwha of [the leader] Te Rakitauneke, and Te Rakitauneke was Ngāti Māmoe” (respondent 14) and “Matamata was a whale and his home was around by Goose Bay” (respondent 2). Whether there might be multiple taniwha named Matamata, or even that the taniwha might be able to change shape, most respondents questioned the authenticity of the narrative provided by Elvy (1949) and concluded that the story was not part of the storehouse of Ngāti Kuri histories. Given these interpretations, any speculation that the narrative reflected experience with past tsunami(s) was not supported.

Corollary deliberations led respondents 18 and 19 to share another narrative about Matamata at Moeraki on the Otago coast (Fig. 1a), with explicit reference to catastrophic inundation of the land from the sea. Independently, these respondents recounted similar understandings. For example: “Matamata was key in the pūrākau [narratives surrounding ancestral deeds and teachings] at Moeraki. I believe it may have been Matamata that spewed forth a great wave full of fish because people were not following the appropriate tikanga [behaviour, correct procedure, lore] when one of the tōhunga [expert in traditional lore, person skilled in specific activity, healer] passed away there. And it was believed that the kaitiaki-taniwha [beings that act as a carers, guardians, protectors, and conservers] or the atua [deity] was so offended at the breach of tikanga that they sent this great wave that inundated [the settlement of] Moeraki. And it was believed that the fish and rotting sea life was on land for a couple of days, and when the gods felt appeased that the people were doing what they should they sent another wave to clean it all up and retrieve the rotting fish. And then … we had no fresh water on our kaika [settlement]” (respondent 18). Both respondents referred to this story as not only recounting a “tidal wave” but also providing an explanation for the lack of freshwater springs at Moeraki.

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Working alongside kin-group members from Ngāti Kuri has confirmed varying understandings (and prior knowledge) of the taniwha narratives from Oaro Lagoon, Lyell Creek, and the surrounding region.

The written version of Carrington's (Reference Carrington1934) narrative was recognised by a select number of kin-group respondents. However, others were also familiar with the story, or aspects of the story, shared by parents and grandparents. Beyond the direct naming of Oaro and the settlement at Omihi, there was deep familiarity with the context-specific details, such as the girls picking konini berries and direct reference to “urukehu” (the olden people who lived in the area), and this led both groups of respondents to conclude that the story is inexorably connected and specific to the area. The significance of the taniwha was also discussed at length by these kin-group members, including reference to its killing and the “disgorging” of the young girl's body. Conversations often centred upon the role of taniwha in providing explanations for, as well as warnings about, hazardous places and extraordinary events. The taniwha's slaying was not, however, considered to be a signal of its end (or by extension the removal of the hazard) but rather that the threat had been removed for the time being. Many of the respondents familiar with the narrative also associated this part of the story with the aftermath of a tsunami and/or storm surge, when the water recedes, and the impacts become visible. These discussions emphasised however that it can be difficult to differentiate tsunamis from storm surges in such narratives, and that such divisions may even be artificial when considering that these narratives were composed at a time before the impacts of colonial cultures. Meanwhile, debates in the geological sciences about the difficulty of distinguishing between deposits left by tsunamis and storms are also ongoing (e.g., Morton et al., Reference Morton, Gelfenbaum and Jaffe2007; Goff et al., Reference Goff, Chagué-Goff, Nichol, Jaffe and Dominey-Howes2012; Dewey and Ryan, Reference Dewey and Ryan2017). Notwithstanding these different views, the collective reflections and interpretations of these kin-group members affirm that the story is not a common narrative for mere entertainment but rather, and more importantly, a memorial to the loss of a young life and a reminder about the tsunami and/or storm surge hazard in and around the lagoon.

Although several scholars have argued connections between taniwha and the transmission of messages surrounding environmental hazards (Orbell, Reference Orbell1985; Galbraith, Reference Galbraith2001; King et al., Reference King, Goff and Skipper2007; McFadgen, Reference McFadgen2007), a number of the respondents in this study emphasised that the role of taniwha is far from limited to an interpretation of natural phenomena. Rather, taniwha also speak to a reverence for Nature's forces and the deities who ruled them, bestowing punishment or protection according to the strictness with which people respected the rules imposed by tikanga (behaviours, correct procedure, and lore), kawa (etiquette, protocol) and tapu (the sacrosanct, forbidden, inviolable; Orbell, Reference Orbell1985; Evison, Reference Evison1993). From this point of view, the fierce behaviour of the taniwha at Oaro is not due to its nature but rather is a consequence of human misconduct.

Two respondents expressed caution about the Oaro narrative, citing both limits to what can be understood when reading Māori narratives translated into English as well as narrative templates in the storyline that are repeated in other stories committed to writing by early ethnographers across the country. Responding to the first point we concur with this caution. However, we are not aware of the existence of a written Māori version of the Oaro narrative, or whether one was ever produced, so evaluating the veracity of Carrington's (Reference Carrington1934) version of the story must rely upon engaging with Māori knowledge holders who continue to keep such narratives active. Moreover, while we concur with views about the critical role of Māori language for understanding and interpreting Māori narratives, characters and their context (Tau, Reference Tau1999; King et al., Reference King, Goff and Skipper2007) we also acknowledge that a first-hand understanding of Māori custom and tradition is required, and that the two are not mutually exclusive. From this point of view, it is not a question of whether participating kin-group members speak the Māori language but rather whether their connection to the Māori world provides a means by which they can make sense of their lives, their circumstances, their practices, and their stories over time (Smith, Reference Smith1999). With respect to the second point, the similarity of the Oaro storyline with others from different regions does raise questions about whether the story might be borrowed from elsewhere and locally customised. A number of scholars point to the East Coast of the North Island as the origin for many South Island traditions (O'Regan, Reference O'Regan1992; Evison, Reference Evison1993; Tau, Reference Tau2003; Prendergast-Tarena, Reference Prendergast-Tarena2008), however whether the narrative from Oaro has been translocated from there or further afield is a topic greater than the scope of this paper can provide. Such uncertainties and diverse realities again emphasise the importance of the inductive methodology applied in this study (i.e., working alongside kin-group members who continue to actively participate in the transmission of such narratives), thereby minimising the chances of turning stories into things that they are not.

Turning to the story of the taniwha from Lyell Creek (Elvy, Reference Elvy1949), some elements within this narrative, such as the name of the taniwha and the physical description of the creek, were well-known. However, the description of the taniwha's shape and form were not familiar to any of the respondents. Rather, most knew of Matamata as the guardian whale of the tōhunga (expert in traditional lore, person skilled in specific activity, healer) Te Rakitauneke from Ngāti Māmoe, the former kin-group to occupy the Kaikōura Peninsula. And, while some respondents openly accepted that there may be more than one taniwha named Matamata and/or that Matamata might even be capable of changing shape and appearance, the lack of context-specific details in the story led most to question the reliability of the narrative, and thereafter to doubt its links with Ngāti Kuri histories. Most respondents concluded that the story most likely relates to the migration southwards of Ngāti Māmoe through the South Island, and therefore any speculation the narrative reflected experience with past tsunami(s) was not supported.

In the course of reflecting on the Carrington (Reference Carrington1934) and Elvy (Reference Elvy1949) accounts, several kin-group members described other stories about uplift of the seafloor and catastrophic saltwater inundations at locations from Mikonui and Peketa in southern Kaikōura (Fig. 1b) to much further south at Moeraki on the Otago coast (Fig. 1a). Like Oaro, these narratives not only point to the potential for reliving the experiences of those who originally shared them (Morrow, Reference Morrow and Murielle Nagy2002), but they have the potential to guide the selection of sites for locating geological evidence of past tsunamis. Around the Kaikōura District such work would respond to the clear absence of palaeotsunami enquiry (Walters et al., Reference Walters, Barnes and Goff2006; McFadgen, Reference McFadgen2007), and potentially link with records of past tsunamis from sites to the north such as Mataora-Wairau Lagoon (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Hayward, Cochran, Wallace, Power and Sabaa2015; King et al., Reference King, Goff, Chagué-Goff, McFadgen, Jacobson, Gadd and Horrocks2017) and Lake Grassmere (Pizer, Reference Pizer2019). This scientific work is crucially important for firming up estimates of the timing of past tsunamis and helping to understand the likely return period for large to great events. Further still, targeted geological investigations across the Kaikōura District might give perspective on the most significant tsunami to affect the Kaikōura coast since written records began, which occurred following the Mw 7.8 earthquake on November 14, 2016 (Power et al., Reference Power, Clark, King, Borrero, Howarth, Lane and Goring2017).

It is worth noting, however, that historical events as described in the kinds of narratives considered here are rarely recalled relative to some fixed point in time. Therefore, applying chronology to the Oaro story maybe likened to historicising a past that was not originally intended to constitute a linear history (Tau, Reference Tau1999). Perhaps, as Cruickshank (Reference Cruickshank1994:408) suggests, “one of the more direct contributions oral tradition can make to academic discourse is to complicate our questions.” In this way, the insights from different ontologies and epistemologies can be used to enhance one another, rather than be viewed as replacements for, or to be incongruent with, one another.

It is evident from this study that collaborative storytelling as a research method is well suited to deliberating the content and meanings within historically-derived, written, ethnographic narratives. By working alongside family groups within which such stories were originally told, and carefully cross-checking the active histories and traditions held by different families and individuals, the authenticity of such narratives has been questioned, while detail has been added to others, or partially so. These outcomes highlight the elemental role of whakapapa (ancestral lineage, genealogy) in framing and comprehending the context of such narratives. They also remind us that such stories are characteristically personal, and that each generation will adapt their stories, add new layers of information, and let things that are no longer relevant drop from their narratives (Binney, Reference Binney1987). Collaborative storytelling offers a way to reclaim stories and culture paying close attention to the context in which narratives are situated, whether external influences are important, and whether the content is vital to cultural endurance and memory. There is also the potential for such an approach to be used beyond Aotearoa-NZ, in a range of contexts, where other Indigenous/First Peoples hold histories of social, political, cultural, and environmental change (Heaton and Snavely, Reference Heaton and Snavely1985; Clague, Reference Clague1995; Nunn, Reference Nunn2018). Further still, engaging in this kind of research can help to promote “plural spaces” of learning that contribute to the development of new questions, new knowledge, and new narratives (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson, Reference Howitt, Suchet-Pearson, Anderson, Domosh, Pile and Thrift2003; Thrush and Ludwin, Reference Thrush and Ludwin2007; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Howitt, Cajete, Berkes, Louis and Kliskey2016).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This study has documented the recollections and reflections of kin-group members from Ngāti Kuri about the potential inclusion of ancestral experience with past tsunami(s) in two ethnographic records from the Kaikōura region. The first ethnographic record by Carrington (Reference Carrington1934) was known by half of the kin-group members interviewed. Some respondents also knew different versions of the narrative, while others had no knowledge of it at all. Most respondents considered the story an “intergenerational” narrative comprising deliberate contextual, historical, and symbolic content about past catastrophic saltwater inundations, and the ongoing risks associated with the lagoon. However, it is difficult to distinguish tsunami from storm surge, as is the case in other contexts. In contrast, any notions of Elvy's (Reference Elvy1949) account of the taniwha, Matamata, from Lyell Creek referencing experience with past tsunami(s) were not supported, with most respondents preferring to link this account to the historical migration of the former kin-group Ngāti Māmoe southwards through the South Island. This research affirms that ethnographic records are not necessarily full or accurate accounts of past events. Further, the voices of those who retain genealogical linkages are essential for affirming, and sometimes refuting, written history. The accounts presented here also contribute to the reclaiming of Ngāti Kuri histories and point to new plural learning opportunities about co-seismic tsunami hazard and history across the region, in a greater project of acceptance of “other” ways of knowing science.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge those members of Ngāti Kuri and Ngāi Tahu whānui who shared with us their histories and insights. We also acknowledge Professor's Walter Dudley, Jaime Urrutia Fucugauchi, and Nicholas Lancaster as well as one anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Stephanie Huriana Martin is thanked for translating the abstract into Te Reo Māori. This work was funded by Environment Canterbury (ECAN Contract: 1025-17/18) and the NIWA Strategic Science Investment Fund— Hazards, Climate and Māori Society (Grant Agreement No. C01X1702).