Introduction

During the first wave of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Canada (March 1 to August 31, 2020), older adults residing in long-term care homes (LTCHs) and retirement homes were disproportionately affected. Those first six months were marked with 7,260 deaths making up 79% of all Canadian COVID-19 deaths (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). The provinces with the highest number of deaths were Quebec, followed by Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia (BC) (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). In Ontario, there were 5,941 reported cases in LTCH residents; among those cases, 1,937 residents (32.6%) died (Public Health Ontario, 2021).

With the onset of the first COVID-19 wave, around March 2020 till the end of the summer, Canadian provinces began enacting and updating visitation policies to restrict access, including that of essential family caregivers (EFCs), to LTCHs to prevent the further spread of COVID-19 (Chu, Wang, et al., Reference Chu, Wang, Fukui, Staudacher, Wachholz and Wu2021). By mid-March 2020, in the provinces of Ontario and BC, Chief Medical Officers issued statements that recommended limiting visitations in LTCHs to only “essential” visitors, referring to a limited group of people who could visit the residents receiving palliative care (Government of British Columbia, 2020a; Williams, Reference Williams2020). Across provinces, the differentiation between “family caregivers” and visitors varied (National Institute on Ageing, 2020), and there was uncertainty about who was qualified to visit, as some families were not allowed to see residents despite providing essential daily care like feeding and toileting (Fooks, Reference Fooks2020). An EFC is defined as any trusted individual chosen by the resident, or a substitute decision maker, who can provide care and companionship to a resident, which includes (but is not limited to) biological family members, friends, and paid companion/caregivers (Government of Ontario, 2021).

Social isolation and its consequences on older adults’ physical and mental health are well established (Santini et al., Reference Santini, Jose, Cornwell, Koyanagi, Nielsen, Hinrichsen, Meilstrup, Madsen and Koushede2020; Sutin et al., Reference Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti and Terracciano2018; Valtorta et al., Reference Valtorta, Kanaan, Gilbody, Ronzi and Hanratty2016), but the pronounced level of prolonged and widespread isolation had not been encountered until COVID-19 (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Donato-Woodger and Dainton2020). Social connections and contact with family and friends are imperative for older adults’ quality of life (Moyle et al., Reference Moyle, Fetherstonhaugh, Greben and Beattie2015). In recognition of the deleterious effects of social isolation, multiple-visitation methods were sequentially implemented for EFCs during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic as the community spread of the virus waxed and waned. Initially, EFCs were only permitted virtual visits using tablets or other devices; this went on for months. Following this period, non-essential outdoor visitations were permitted, meaning that the LTCHs that were not experiencing an outbreak were able to designate an outside area to conduct visitations during the summer of 2020 (Government of Ontario, 2020a). In Ontario, these outdoor visits were restricted to approximately 30 minutes with only one visitor who could verbally confirm that s/he had received a negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) COVID-19 test; the visitor was to wear appropriate personal protective equipment (i.e., mask, gown, gloves) and physically distance (i.e., stay 6 feet away from the resident). Moreover, measures requiring EFCs to provide negative COVID-19 tests for outdoor visitation were unduly onerous as these visits were at low risk for COVID-19 transmission given they took place outdoors with distanced and masked individuals (Stamatopoulos, Reference Stamatopoulos2020). On July 15, 2020, after ongoing public advocacy and criticism, the Ontario Provincial Government updated the visitation directive to allow outdoor visitations to occur without the need for a COVID-19 test (Government of Ontario, 2020b). Finally, by July 22, 2020, indoor visitation had resumed with strict guidelines in Ontario (Government of Ontario, 2020b), due to the low incidences of COVID-19 cases (102 cases provincewide on July 14, 2020) (Public Health Ontario, 2020). LTCHs began to allow indoor visits - if there were no outbreaks within the home at the time. Homes were only required to provide these visits once a week, and they had to be pre-scheduled. Each resident could have a maximum of two visitors who were required to provide a negative COVID-19 test, follow public health protocols, and meet the residents in a supervised common area (Government of Ontario, 2020b). Although visitation policies allowed in-room visits by then, it depended on the decisions of the individual LTCHs (Government of Ontario, 2020b), and their outbreak status that often led to suspended visitor access. On September 2, 2020, a revised policy for “Resuming Visits in Long-Term Care Homes” granted “essential caregiver” status for up to two people, and these designated caregivers could maintain their visitation access irrespective of outbreak status (Government of Ontario, 2020c).

Meanwhile, in BC, access to the residents in the majority of LTCHs was restricted starting in March 2020, with the exception of palliative care visitation by EFCs (Government of British Columbia, 2020a). By June 30, 2020, the policy was updated, enabling residents to receive a social visit by a designated visitor. However, the designated visitor could not be changed (Pon, Reference Pon2020), and each LTCH determined the frequency and duration of the visits (Pon, Reference Pon2020). The designated visitor status could be appealed to BC’s Patient Care Quality Office (British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, 2021). Nearly a year later, on April 1, 2021, BC’s provincial policy was amended to allow up to two visitors plus a child to visit and the addition of physical touch between resident and visitors (without requiring supervision), with infection prevention and control measures in place. Unlike Ontario’s sector-wide directive on EFCs’ access to LTCHs that came into effect in September 2020, individual LTCHs across BC were granted discretion to decide who was approved for designated visitor status within the first year of the pandemic. At the time of this study being conducted, most residents in BC did not have a designated visitor on file (Schmunk, Reference Schmunk2022), and a survey by the Office of the Seniors Advocate British Columbia found that more than half of family applicants were denied designated visitor status in the first four months of the pandemic (Office of the Seniors Advocate British Columbia, 2020).

EFCs play a vital role in the provision of care in LTCHs (Baumbusch & Phinney, Reference Baumbusch and Phinney2014; Bern-Klug & Forbes-Thompson, Reference Bern-Klug and Forbes-Thompson2008; Puurveen et al., Reference Puurveen, Baumbusch and Gandhi2018). A qualitative study conducted in the United Kingdom examined the role of families in monitoring the health status of LTCH residents and found that families were able to detect and alert the LCTH’s care team to early changes in residents’ health status (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Blighe, Froggatt, McCormack, Woodward-Carlton, Young, Robinson and Downs2018). Families provide more than physical and emotional care; families serve as advocates for the residents, assist in the care of other LTCH residents (Puurveen et al., Reference Puurveen, Baumbusch and Gandhi2018), monitor the care provided by LTCH staff (Baumbusch & Phinney, Reference Baumbusch and Phinney2014; Bern-Klug & Forbes-Thompson, Reference Bern-Klug and Forbes-Thompson2008; Puurveen et al., Reference Puurveen, Baumbusch and Gandhi2018), and share the residents’ life stories and beliefs with the staff (Bern-Klug & Forbes-Thompson, Reference Bern-Klug and Forbes-Thompson2008; Powell et al., Reference Powell, Blighe, Froggatt, McCormack, Woodward-Carlton, Young, Robinson and Downs2018; Puurveen et al., Reference Puurveen, Baumbusch and Gandhi2018). Despite the multiple roles families play in caring for residents, their labours are often undervalued and “invisible” (Baumbusch & Phinney, Reference Baumbusch and Phinney2014).

EFCs faced unprecedented policies that prevented them from visiting and providing essential care to the residents that could not otherwise be provided by the LTCHs (Gaur et al., Reference Gaur, Dumyati, Nace and Jump2020; Schlaudecker, Reference Schlaudecker2020). Media outlets widely documented cases of the families’ anguish, frustration, and guilt at seeing the residents deteriorate over months (e.g., Harris, Reference Harris2020; Mauro, Reference Mauro2020; Roumeliotis & Mancini, Reference Roumeliotis and Mancini2020). Yet, at the time of this study, little research had been published about EFCs’ experience of visitations throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Cipolletta et al., Reference Cipolletta, Morandini and Tomaino2021; Vaitheswaran et al., Reference Vaitheswaran, Lakshminarayanan, Ramanujam, Sargunan and Venkatesan2020; Verbeek et al., Reference Verbeek, Gerritsen, Backhaus, de Boer, Koopmans and Hamers2020), particularly within the Canadian context. As the pandemic is still underway in Canadian LTCs and other parts of the world, highlighting EFCs’ perspectives on and experiences with these visitation policies and modalities may inform ongoing pandemic responses in a way that considers the well-being of the residents and EFCs. This study aims to examine the experiences of EFCs’ visitations with LTCH residents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

This study uses a descriptive qualitative approach to provide a comprehensive summary of events articulated in the everyday terms used by the participants (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). This approach aims to stay close to the stories and words used to describe a phenomenon (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). The research was inductive and exploratory in nature. This study was approved by the following Research Ethics Boards: University of Toronto (REB #40070) and Ontario Tech University (REB #16086).

Participant Recruitment

The recruitment of EFCs occurred on social media (i.e., Twitter) from the accounts of the Principal Investigators (PIs) (CC, VS). Twitter was selected to disseminate the study’s recruitment flyer because the timeliness of the study’s topic could be shared across a larger audience platform. As well, “retweets” could encourage snowball sampling when tweets were retweeted/shared amongst other Twitter users (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Jackson, Goldsmith and Skirton2014). Potential participants who self-identified as EFCs and met the following five eligibility criteria were invited to participate: (a) were family members of residents living in an LTCH who were restricted access to the LTCH residents due to policies related to COVID-19; (b) were able to speak and understand English; (c) were able to provide informed consent; (d) lived in Canada; and (e) had Internet access. The e-mail communications between PIs and potential participants detailed the study’s aim, participants’ right to confidentiality, their ability to withdraw from the focus group (FG) at any point, and the small honorarium in the form of an electronic gift card that was provided to each participant. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants, with the intention to recruit an equal number of male and female EFCs.

Data Collection

Demographic information and other qualitative data were collected using a survey on Qualtrics prior to the virtual FGs. The survey gathered information on primary EFC status, age, gender, and employment, as well as the characteristics of the LTCH residents’ living arrangements (e.g., length of stay at the home, LTCH ownership, type of room), pre- and post-pandemic visitation frequency and duration, and EFCs’ perception of the impacts of the restrictions on the residents’ quality of life. Data collection occurred between January 2021 and March 2021 when a total of seven 90-minute FGs consisting of four to five EFCs (n = 30) occurred on Zoom, a video-conferencing platform. FGs were conducted by province to account for time differences and to accommodate the schedules of the participants.

Both PIs (CC, VS) were present for all the virtual FGs. Group-based interviews encourage in-depth discussion amongst the participants as they build upon each other and can share different perspectives of an experience (Sagoe, Reference Sagoe2012). Before initiating the focus groups, the PIs asked participants to select pseudonyms or be randomly assigned a number by the PIs to protect their identity and facilitate the discussion. For the duration of the FGs, EFCs all had their cameras on.

One PI (VS) followed an open-ended, semi-structured interview guide during the FGs to examine EFCs’ experiences with visitation policies (e.g., How did you find out about the visitation policies? What alternative methods of communication did you use to keep connected with the residents?). The question guide had been previously pilot-tested by other members of the research team for clarity. Another PI (CC) made observational notes related to participants’ body movements and emotions, and also prompted participants to clarify or elaborate on their experiences. At the time of the study, participants were aware that both PIs (CC,VS) are both professors at Ontario universities. The PIs are also both women from different disciplines (CC holds a doctorate in Nursing, and VS has a doctorate in Sociology); both had expertise in qualitative research and no prior relationships with the participants. The PIs debriefed after every FG to identify any potential codes and themes, and also to slightly modify the interview guide based on the previous FGs, if needed. Data collection was stopped once information power was achieved. The PIs determined that there was sufficient information power according to Malterud et al. (Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2016) as determined by the aim of the study, sample specificity of EFCs with lived experiences, quality of dialogue and richness, and their inductive analysis strategy (Malterud et al., Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2016).

Upon explaining the FG, the PIs reminded participants that if at any point during the FG they wish to step away, they were able to do so. Many of the participants showed compassion towards each other, and some of them also cried during the FGs when telling their own stories and reacting to other stories. In such events, they were asked if they wanted to take a break and turn off their video, but no one did. There was no attrition or participant withdrawal over time, and no focus groups were repeated.

Data Analysis

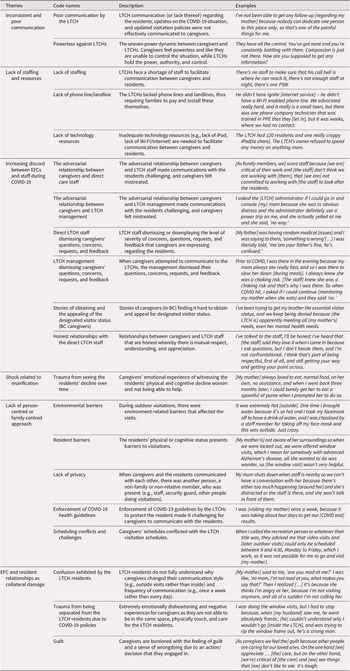

The FG recordings were shared with the project research assistant (AY) who transcribed and de-identified the EFCs’ data. On NVivo 12 software, data analysis using the thematic coding technique based on Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) work was followed during the line-by-line coding. This approach has been widely used and accepted as robust across a wide range of disciplines, including human health research (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2014). The coding process involved familiarizing with the data, producing initial codes, identifying patterns or themes across data, reviewing themes, defining and naming the themes, and writing the manuscript (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2014). First, researchers became familiar with the data content through transcribing the audio recordings and reading the transcripts. Common salient topics or themes from the reading of the transcripts and observational notes were used to build the foundations of the preliminary codes. These codes were refined by assessing for any similarities or differences and then amalgamating/collapsing and sorting these into themes. Afterwards, to check the reliability and validity of the coding names and subsequent descriptors, the coding dictionary was evaluated by each researcher, and, during the team’s bi-weekly meeting, any discrepancies in the codes were addressed. Once the codes were finalized, a coding tree was created (Table 1). The study was conducted and reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Table 1. Coding tree

Sample and Participants

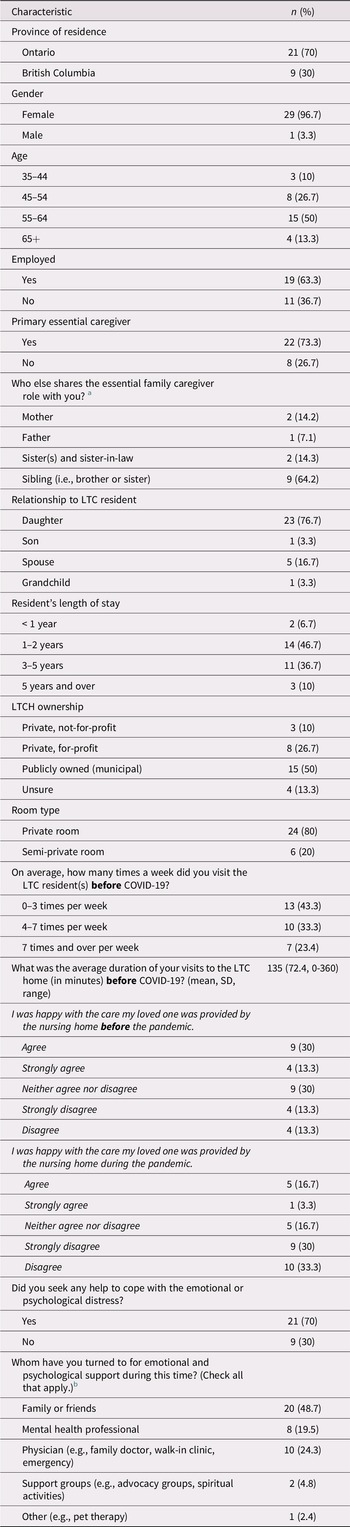

Table 2 outlines the attributes of the study participants and LTCHs. Thirty EFCs were included in the study, with 21 from Ontario and 9 from BC. The sample was largely composed of women (96%), and half of the EFCs (50%) were between the ages of 55 and 64. The majority of EFCs were employed (63%). EFCs were mainly the daughters of the residents (76%), with most residents having lived in the LTCHs between one and two years (46%) or three and five years (36%). The LTCHs where the residents lived were mainly publicly owned (municipal) (50%), followed by private, for-profit (26%), and private, not-for-profit (10%), with most residents living in private room accommodations (80%).

Table 2. Attributes of the study participants and LTCHs (n = 30)

a The percentages are calculated out of 14 responses, due to missing data.

b The percentages are calculated out of 41 responses, due to the question allowing multiple answers.

Table 2 also summarizes the participants’ pre- and post-COVID-19 caregiving frequency and duration within LTCHs, as well as the support they received to manage emotional and psychological distress. Prior to COVID-19, 33 per cent of EFCs would visit four to seven times a week, and 23 per cent visited more than seven times. The pre-COVID-19 visits commonly lasted for an average of 135 minutes (2 hours 15 minutes). In response to the statement, I was happy with the care my loved one was provided by the nursing home ‘before’ the pandemic, 43 per cent of participants were happy with the care. But in response to the statement, I was happy with the care my loved one was provided by the nursing home ‘during’ the pandemic, only 20 per cent of participants were happy. Most EFCs (70%) reported seeking help to cope with the emotional and psychological distress related to the situation in LTCHs. They sought support from family or friends (48%), physicians (24%), and mental health professionals (19%).

Findings

Six themes related to the experiences of EFCs during COVID-19 visitation policies within LTCHs were identified: (a) inconsistent and poor communication; (b) lack of staffing and resources; (c) increasing discord between EFCs and staff during COVID-19; (d) shock related to reunification; (e) lack of a person-centred or family-centred approach; and (f) EFC and resident relationships as collateral damage.

Theme 1: Inconsistent and Poor Communication

EFCs from all the FGs reported feelings of frustration due to the inconsistent rules around visitations between LTCHs. The visitation directives from the respective provincial Ministries of Health were interpreted and implemented inconsistently at the LTCH level, which resulted in variations across LTCHs. The lack of ministry oversight and poor visitation planning by the LTCHs caused EFCs to feel frustrated. They perceived their LTCHs as disorganized, particularly from the lack of communication and follow-up about critical matters like the well-being of the residents and updates on the COVID-19 situation within the homes (e.g., the number of positive cases). Additionally, policies were rapidly changing – often weekly – but changes to policies or visitation rules were not effectively communicated to the EFCs. Consequently, families showed up for visits and were denied entry, or they were told they were unable to visit but were not updated when the restrictions were lifted, all of which caused additional distress. The perceived obstruction of knowledge sharing by the LTCHs to the family members shaped the power dynamic in a way that made EFCs feel powerless. A family member commented, They have all the control. You’ve got none and you’re constantly battling with them. Compassion is just not there. How are you supposed to get any information? (EFC “1,” FG1). This placed the onus on the family members to reach out to the homes by calling multiple times a day to probe for information, leaving them waiting anxiously. As two EFCs described:

When I reached the clinical director that day after the six weeks, I asked [the clinical director], so I’ve been trying multiple times for days to reach you to ask for permission to be at the bedside with my mother and [the administrator] says to me, “Oh, we were cleared from the outbreak, two weeks ago, you know you could have been in two weeks ago.” They never told me. I said to her, I will never forgive them for that. I feel like I was punished… I’ll never forgive them for that. I only had four visits with her, before she died. It was cruel… It’s really brutal on top of the pain that you just feel being separated and worried constantly, in anguish about how your loved one is. (EFC “Morgan,” FG1)

I would come home or be home every day, and my family would … say the [home administrators] can’t do this to us, they can’t do this to us … It was devastating. They can’t keep locking us out … It was like they were playing God. The [home administrators] saying when you could visit, when you couldn’t visit, “Oh didn’t you know you were allowed to take him out the front door and go for a walk? Didn’t you know that?” and I was on top of everything. It was just unbelievable. You would think that would be the first thing that they would communicate, for the benefit of the residents … You’d think they do it immediately to benefit the residents. Immediately. (EFC “2,” FG1)

The poor communication between the homes and the EFCs pertained to critical health information such as the COVID-19 status of the residents. One family member described their experience:

When she had COVID, maybe we got a phone call, maybe we didn’t. If we didn’t get one, did that mean she was okay or not okay, wondering if they forgot, there was no weekly news bulletin, nothing. Nothing came up. There was no open form of communication. (EFC “2,” FG4)

Theme 2: Lack of Staffing and Resources

EFCs all reported experiences where their visitations were negatively impacted due to the poor organization of the LTCHs, and lack of staff while the present staff were ill-equipped to handle the additional demands of supervising and facilitating family visitations on top of their usual workload. Family members recognized the difficult position of the staff and the lack of resources and support provided to them by the government and LTCH organization. One family member explained:

I don’t blame the care staff. I’ve never had a complaint with the care staff because they are doing, I believe, as much as they can with 3.5 hours, man-hours, that are allotted to each resident. So, when my mom is still in bed at 2:30 in the afternoon, I know they don’t have the 20 minutes that I might have to try to get her dressed. Yeah, I understand that. But I do have an issue with the Directors of Care, with making their own decisions on the rules that our [government] and Ministry of Health put in place – that they use their discretion to keep as many of us [family members] out as possible because they are afraid of COVID getting in. So [the directors] just lock everyone out … that’s who I have a big issue with at that home. (EFC “1,” FG4)

The reliance on staff during visitations made it challenging for EFCs to see the residents, especially considering that, before COVID-19, LTCHs were already understaffed and burnt-out: Facetime had to be [set-up] by a shortage of recreation staff, you’re very limited in how you could even see your loved one (EFC “4,” FG6). Several EFCs relayed stories of unanswered phone calls and video calls, where the device was held too far for the resident to see or hear, and scheduled video calls being cancelled at the last minute by staff. After months of experiencing these staffing challenges, EFCs were increasingly concerned about not being welcomed and utilized as resources during the pandemic, as exemplified by one family member:

With no extra staff and knowing how short-staffed they are all the time, to kick us out, at a time when they would need us more was unbelievably frightening. (EFC “2,” FG1)

In addition to the staffing shortages, EFCs experienced an inadequate supply of technical resources, which served as an additional barrier for EFCs who relied on virtual visits to see the residents. Virtual visitations were short and difficult to schedule at some homes due to the lack of iPads that had to be shared amongst a large number of residents, or in homes without Wi-Fi or Internet access on certain units. Family members informed directors and owners about the insufficient number of staff and devices – and, in some cases, involved the media – but homeowners did not address their concerns. Two family members stated:

The [LTCH] had 120 residents and one really crappy iPad [to share]. The LTCH’s owner refused to spend any money on anything more, so I actually advocated … a heartfelt cry, and I actually got the media attention as well. This is bulls*** … like, what the hell? What do you mean you won’t go and spend money? People are dying and we can’t even say goodbye over Skype. (EFC “Flow,” FG1)

The Director of Care said to me, “I can’t do anymore, if [the staff] won’t do [a task], I can’t make them do it, and if I push them too hard, they’ll quit and there’s no one else to hire to replace them and we’re already so short staffed.” So that’s another reality of the short-staffed situation is that the people that are there … can do whatever they want or not do whatever they want. It’s scary. (EFC “3,” FG4)

Theme 3: Increasing Discord Between EFCs and Staff During COVID-19

Many of the participants spoke about the discord and tension between the LTCH staff/management and the EFCs. This discord is reflected in the survey responses as 19 out of 30 participants indicated that they were unhappy with the care the residents received during COVID-19, compared to only 8 participants who were unhappy with the care received before the pandemic. EFCs reported feeling mistreated, not welcomed, or like an inconvenience for the staff. Underlying these negative feelings, EFCs felt that they were not recognized as critical partners, as often their questions or concerns were dismissed. The EFCs’ fear of being unable to provide care for the residents was exacerbated as LTCHs were already chronically strained with a lack of human resources. This led to family members vocalizing their concerns face to face or in the form of phone calls and e-mails:

[As family members, we] scare staff because [we are] critical of their work and [the staff] don’t think we are working with [them], that [we are] not committed to working with [the staff] to look after the residents. (EFC “Morgan,” FG 1)

Some EFCs expressed the opinion that the LTCHs were being punitive towards the family, by scrutinizing the EFCs’ compliance with public health protocols:

[It felt] like we were being reprimanded. When I tried to get my mom out in the fall for a walk, my husband would wait outside and then we’d wheel her out because it was a bit better [outside]…and the [long-term care home] coordinator [would] be yelling at me [to] social [distance]…you’re being punished for everything and always, “What are you doing,” “Don’t touch her like that,” [and] “Make sure your mask is on.” There were times I come home in tears because I feel like I have PTSD from this last spring, [the LTCH staff] are making us feel so bad. (EFC “4,” FG5)

In some cases, particularly in BC, EFCs recalled the challenges of obtaining a designated visitor status that could grant them entry into the homes. Many EFCs expressed frustration when the government’s patient care quality office would indicate that the residents’ needs were met, thus the appeal for status was rejected. EFCs felt that they were being mistreated, as some EFCs did gain status but the process was not transparent for all. In one case, a participant recalled how her status was only granted “conditionally,” meaning that once the needs of the residents had been substantially satisfied, the status could be revoked at any time. She described her experience:

We appealed in our appeals process … and [the appeal] went around and around in circles, we were completely unsuccessful until we were very outspoken in the media. I went on a radio talk show and had our local TV news to do a story about my mom. Twenty days after that story aired … she’d lost 25 pounds and the home contacted us to give us [an] essential caregiver status … they said, “We’re going to give you a status, but once you fatten her up four kilograms we’re going to revoke your status.” So, they couldn’t even let us enjoy the news for 12 hours, they told us that the next morning. (EFC “1,” FG6)

Lastly, there was a small number of EFCs who spoke positively about specific staff members at their homes who attempted to address their concerns, demonstrating the importance of positive relationships during this difficult time when families felt conflicted with the LTCH and staff:

I had developed a relationship with one of the PSW that cares for my mom. Her and I were texting, and I think that she was the only one who tried to improve the situation. I didn’t hear anything from management unless I contacted them first. (EFC “1,” FG2)

I tried to bargain with [the staff], like, “Can I give a hug to my husband? like pretend you didn’t see me?” They said no, they can’t do that, but they would really love to let me do that. (EFC “2,” FG2)

During the outdoor visits [a nurse] actually arranged for me to be able to safely cut my husband’s hair sitting on the grass. She brought me PPE, she let me cut his hair and she brought us non-alcoholic wine because I told her that we used to have a drink at home, while I cut his hair … she’s compassionate. She is absolutely [a] lifesaver! (EFC “5,” FG5)

Theme 4: Shock Related to Reunification

After being locked out of the LTCHs for several months and receiving minimal communication from them, EFCs were not aware of the extent of physical and cognitive deterioration until in-person visitation resumed. They all experienced a “shock” when they were reunited with the residents. EFCs were in “disbelief” as they noticed significant health and personality changes that had occurred in the residents. Three family members recalled:

[My mother] was skeletal and then I got her into the room and kind of, like, took her sweater off and I looked at her and her ribs were sticking out. I can’t even fathom how much weight [she has] lost. I got them to check her weight, she was down to 68 pounds! Now she’d been tiny before, but she was down to 68 pounds or 65 pounds. (EFC “3,” FG6)

[My mother] was a voracious eater while I was there in March feeding her. Often, she’d have more than one serving of meals, [and] she was walking with a walker. She couldn’t get herself out of a chair, but with help she would get up and then she could walk with her walker … [By] the end of March, she had lost 40 pounds. She was left sitting in her room for so long that she can’t walk anymore. She was in a wheelchair by May. (EFC “5,” FG 4)

My very first visit after the second wave, when I was allowed in for a 30-minute visit, I picked up that [my father] had severe cellulitis in both lower limbs. I picked up that he had a severe fall because the call bell was under his bed, so he fell, and he had this huge bruise. I would strip that man down and every time there’s bedbugs; there’s all kinds of bites on him. (EFC “1,” FG3)

Many EFCs shared stories of long-standing fears and worries related to LTCHs not being able to provide the care necessary to maintain the residents’ physical, cognitive, and emotional well-being. This guilt and fear started when they first admitted their family members into LTCHs, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Seeing the decline of the residents upon reunification was in many cases a “nightmare” that came true for EFCs.

Theme 5: Lack of a Person-Centred or Family-Centred Approach

EFCs expressed the lack of collaboration and partnerships that the LTCHs had with the families, along with the lack of forethought about the needs of the residents when implementing visitations. Many EFCs felt that visitation policies ignored the residents who had severe physical or cognitive impairments and those who depended on EFCs for daily care like eating, toileting, and social contact. One EFC described how they perceived being unable to see their mother for five months resulted in confinement syndrome:

[My mother hadn’t] been able to have physical contact until September. How is that even human? In terms of, [not having] physical contact for months and months on end. We don’t even treat prisoners that way. It’s insane. It’s absolutely insane … there [was a scientific report released and] they talked about confinement syndrome. Confinement syndrome is exactly the syndrome that they use to get rid of solitary confinement in prisons, like this is the level that we’re operating on. It’s just beyond – I can’t even put words to it. We’re talking about care in long-term care facilit[ies] on the same level as prisons. There’s no humanity; it’s ridiculous. It’s absolutely insane. (EFC “3,” FG2)

EFCs recalled how their visitations were poorly planned by the homes without consideration for their circumstances. A common experience was that LTCHs scheduled video visitations during working hours when EFCs were not available: When I called the recreation person or whatever their title was, they advised me that video visits and [later outdoor visits] could only be scheduled between 9am and 4:30pm, Monday to Friday, which I work, so was not possible for me to go and visit [my mother]. (EFC “4,” FG3)

Additionally, while EFCs were willing to get nasal swab tests for COVID-19, they needed to find an appropriate testing facility, schedule a test, wait for the results, and repeat it once or twice each week to continue regular visits to the residents. This was very time-consuming, given their other life obligations. Obtaining a negative COVID-19 test was required before each visit and participants in our study reported being tested more than 50 times within a period of eight months for the sole purpose of being able to visit the residents. One EFC noted that COVID-19 tests were a very physically uncomfortable experience:

I just had a COVID test. So, this morning before my husband’s birthday celebration, I had a terrible nosebleed because they’ve been digging up my brain for months. (EFC “5,” FG5)

EFCs recalled the lack of consideration towards the families and residents when LTCHs organized the visitations, which often took place in inappropriate public settings within/near the homes. EFCs described how they had to yell when conversing with the residents due to physical distancing measures and to compete with the background noise (e.g., LTCH lobbies, parking lots) without any privacy during visits. Outside visitations were also subject to environmental elements, such as wind, heat, or rain. All visits were closely scrutinized by staff members and/or security guards employed by the home. An EFC recalled “begging” staff to improve the visitations:

[I begged the staff] could you please find a way to do an outdoor visit, find a way to let them hear us, find a quieter room – there must be an empty room in this place. So I felt like I was constantly trying [to] give them suggestions [to make things better]. And every time it was, “We’ll take that under advisory to our next monthly meeting” and I’m thinking, “These residents don’t have months.” We’ve lost an entire year with our loved ones, and you can’t get that back. (EFC “2,” FG4)

Furthermore, the use of security guards was problematic for many EFCs as it represented an “enforcer of rules” which was counter to the notions of person-centred or family-centred care. While the barriers to LTCHs’ visitation could have been addressed and mitigated, LTCHs offered little to no alternatives to accommodate. A family member recalled an experience with the security guard and the overall conditions of the family’s visitation experiences:

[Once outdoor visits were allowed] we visited outside, and they had a security guard posted there. The security guard was very surly. I have to drive four hours to see my mother, to drive four hours just to visit her for 30 minutes outside and turn my car around and drive another four hours home. So when I got there … I saw the security guard and our visit was at 2:45pm and I got there [at] 2:46pm. I remember, like, specifically looking at the clock and I said, “I’m here to see my mom” and his first answer to me was, “You’re late.” I couldn’t believe [the lack of empathy]. So anyway, I complained about him. We had outdoor visits and it was at the side of a parking lot, outside of the building, so trucks, cars [were in the background]. Our hearing is pretty good but not that good. On windy days, the wind would be whipping around, I had to say to [the staff], “Can you dress her properly, because she’s not even dressed for an outside visit?” (EFC “4,” FG2)

Throughout the pandemic, EFCs felt there was a lack of commitment from the government and the LTCHs to reconnect families and residents. For example, once there were data indicating that the risk of COVID-19 transmission outdoors was lower compared to indoors (Bulfone et al., Reference Bulfone, Malekinejad, Rutherford and Razani2021), family members questioned why they were unable to have outdoor visits. The COVID-19 safety protocols that required physical distancing measures and personal protective equipment (Government of Ontario, 2020a) were not aligned with what family members considered person- or resident-centred protocols. This was especially the case for EFCs and residents with physical and cognitive impairments. While families understood it was imperative to keep residents safe, the imbalanced and hyper-focused approach to preventing COVID-19 had a deep emotional toll on residents and EFCs, as one EFC described:

Sometimes it just so overwhelming and surreal. It just seems like we’ve lost, barely holding on to reality. The difference between a long-term care home [compared to] an institution [is that it’s] a home. A home operates differently than an institution, [the residents and family members] are partners with [the decision makers]. There needs to be balance, and it doesn’t need to be perfection and I’m not expecting perfection, but needs to be balanced between controlling COVID-19 and everything else, like other aspects of health and life. (EFC “3,” FG2)

Theme 6: EFC and Resident Relationships as Collateral Damage

EFCs separated from the residents expressed the trauma of hearing about and witnessing the inadequate care provided in LTCHs, the outbreaks in the homes, and residents being isolated. The guilt of putting their family members in LTCH worsened as EFCs were unable to provide help to the staff due to the LTCH visitor restrictions. In addition, there was a sense of hopelessness and loss, whereby EFCs separated from their parents, grandparents, or spouses all lost valuable time with the residents:

We’ve lost an entire year with our loved ones and you can’t get that back and that’s the disheartening thing … Having lost a year, with no hope on the horizon, I feel like we’ve just lost the last bit of time. I want to hug her. (EFC “2,” FG4)

Further, residents were also harmed by these policies and protocols. Simple and meaningful acts, such as EFCs being able to comfort the residents through physical touch (e.g., holding hands while wearing gloves), were not allowed which caused distress for EFCs and residents alike. In particular, EFCs of residents with dementia and the residents themselves experienced strong emotional reactions with each visit; residents could not understand the reasons why their families were not visiting or entering the facility and assumed that their families thought they were a burden and had abandoned them. Consequently, EFCs expressed irreparable guilt and long-lasting harm to their relationships with the residents. One EFC described her experience with visits through the window and on either side of the fence:

I did [have some] window visits. The problem with window visits in the summer was that [my mother] has a very tiny window so she was not able to even hear me through it. She was required to wear a mask inside, even though there was a very tiny window between us, and I was outside and masked. It was on the sunny side of the building so in July and August I think I walked home with heat stroke a couple times because sitting there in the heat was brutal. Then I think she was just very confused, or she just thought I was being strange, or was being stupid, because why aren’t you coming in? Why are you at my window? … When we did the fence visits we were on the other side of the fence [6 feet away], we can barely see each other [because of my mother’s eyesight]. So, it was sort of useless. I actually stopped doing the [fence visits], because I think she just got more upset [with] the fence visits. (EFC “2,” FG2)

The EFCs’ proximity to the residents was impeded by physical barriers like a window or fence, which created feelings of guilt, worry, and sadness:

[Through the window] I could see [my mother] deteriorating right before my eyes and then five months to the day, August 14, she told [the staff] she wanted to give up. My sisters and I stood outside her room the whole day and she reached out towards the window and all we could do is put our hands on the window. That is the image that stayed in my mind. (EFC “1,” FG1)

Discussion

This qualitative study explored EFCs’ experiences with restricted visitation policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Six themes illustrate the common challenges EFCs experienced throughout the lockdown period during the different types of visitations: (a) inconsistent and poor communication; (b) lack of staffing and resources; (c) increasing discord between EFCs and staff during COVID-19; (d) shock related to reunification; (e) lack of a person-centred or family-centred approach; and (f) EFC and resident relationships as collateral damage. In periods of stricter and gradually more lenient policies, these themes were consistent. The findings of this study deepen our understanding of EFCs’ experiences with these rapidly introduced policies into LTCHs, that in many cases, LTCHs were unable (and sometimes unwilling) to support EFCs’ sustained and meaningful access to the residents. Overall, these themes illustrate an emotionally charged and negative experience for EFCs as they were confronted with frequently changing visitation policies and types of visitations (e.g., virtual, window, outdoors, indoors). The long-standing systemic weaknesses of the LTCH sector were amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic (Béland & Marier, Reference Béland and Marier2020), creating a milieu in which there was poor communication, significant tensions between the staff and EFCs, and inadequate family-centred approaches that are outlined in the Residents’ Bill of Rights. Moreover, our findings reflect important social and structural impacts on EFCs’ experiences and their understanding of care provision. For the majority of women in the labour market, caregiving is increasingly viewed as “work” beyond normative family expectations, which has created greater demands for public services and care (Guberman et al., Reference Guberman, Lavoie, Blein and Olazabal2012).

The findings from this study highlight several concerns at the individual, home, and system levels, which are consistent with the conceptual framework by Dahlgren and Whitehead (Reference Dahlgren and Whitehead1991) that outlines interconnected layers of influence on health and experiences with health services. This framework is useful to scaffold our discussion as it identifies multiple determinants at different levels “amenable to organised action by society” (p. 22) and expands our perspectives outwards to the possible role of upstream determinants bringing into focus the multifaceted solutions required (Dahlgren & Whitehead, Reference Dahlgren and Whitehead2021). First, at the individual level, several EFCs described how they felt that they “were on the same team with the LTCH staff” before the pandemic, but that this relationship was replaced with one of tension and opposition based on their negative interactions with LTCHs’ staff and management. This is a potential long-term issue that raises questions about how these damaged relationships can be repaired and refocused on the well-being of the residents post-COVID-19. In our findings, some EFCs expressed disappointment with individual staff whom they had trusted in the past, and this loss of trust in the home extrapolated into a mistrust of the general health care system’s ability to provide competent care. Previous literature about Canadian family caregivers of older adults with dementia indicates that caregivers’ mistrust is related to fear and risk of harm through inadequate care, which can lead to caregivers shouldering even more of the complex care demands of the residents (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Rosenberg, Kontos, Cameron, Mihailidis and Nygård2017). A decrease in trust is a cause for concern from a policy standpoint given that the reality of caregiving is an upward trajectory of duties; as care needs will only increase indefinitely, EFCs are at a high risk of burnout. EFCs in our study spoke about the toll brought on by their feelings of concern and burnout which developed as a consequence of not being able to visit and their poor visitation experiences. Burnout is commonly experienced by caregivers of older adults with dementia, and they report poorer quality of life (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Monteiro, Bento, Hayashi, Pelegrini and Vale2019). Similarly, our study’s participants reported that they felt severe psychological and emotional distress and sought assistance from family and friends as well as medical professionals to manage their stress-related symptomatology. These coping mechanisms and actions are common (Lin & Wu, Reference Lin and Wu2014), and additional resources should be focused on assisting EFCs to cope with the moral distress they have experienced.

At the LTCH level, the policies and home approaches, such as poor scheduling and hiring security guards, reported by EFCs did not exemplify principles or mandates based on person-centred and family-centred care, thereby precluding a collaborative relationship between EFCs and staff. Organizations have advocated for more patient- and family-centred approaches (Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2020; Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2015). Instead, the actions of LTCHs’ administrators and the social dynamics throughout the COVID-19 pandemic indicated to EFCs that the homes were complicit in the unintended neglect of care for the residents. Another recent study highlights the collective trauma suffered by family caregivers (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2022a). Reconciling and rebuilding the trust lost throughout the pandemic will require actions that reaffirm the value of care partnerships between residents’ families and staff. Homes can engage in policy and practice activities that increase communication (e.g., meetings, support groups) and transparency of decision making at the home level to create environments where both LTCH staff and administrators as well as family members are empathetic with one another and view each other as partners in care (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth and Lepore2009). Future areas of collaboration between LTCHs and families are the development of an outbreak plan, as well as how education and training in infection prevention and control modules can be provided (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Straus, Flood, Keefe, Armstrong, Donner, Boscart, Ducharme, Silvius and Wolfson2020; World Health Organization, 2020).

Thirdly, at the health care systems level, there have been calls to refocus on a family-centred care approach whereby active collaboration and communication with families are critical processes in care and policy-level decision making (Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2020; Dokken et al., Reference Dokken, Johnson and Markwell2021; Fooks, Reference Fooks2020; National Institute on Ageing, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Our study findings align with a recent 2020 patient ombudsman report examining the overarching experience of EFCs and residents across different care settings in Ontario (i.e., LTCHs, community care, public hospitals) (Fooks, Reference Fooks2020). In particular, the report identified similar themes related to inadequate communication by the LTCHs, poor quality of care, lack of staff, and COVID-19 testing (Fooks, Reference Fooks2020). As noted in our study, many EFCs reported forms of self-identified trauma due to the stressful events experienced throughout the various visitation policy changes, and in trying to visit the residents. From a recovery perspective, EFCs require accountability and the mechanism to support accountability in multiple jurisdictions. Our findings also bring into focus how these restrictions can create additional physical and emotional harm (Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2020; National Institute on Ageing, 2020); for example, in our findings, the visitation policies unintentionally damaged the relationships between EFCs and the residents. As well, some EFCs parallel the experiences of LTCH residents to the confinement syndrome reported by prisoners. This issue was also raised in France’s LTCHs (Diamantis et al., Reference Diamantis, Noel, Tarteret, Vignier and Gallien2020), thus future pandemic responses and policies should take a holistic harm-reduction approach to address potential consequences (Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2020).

Moreover, changes to the LTC sector will require coordinated action between the federal and provincial/territorial governments to fund equitable wages and benefits that will remain post-pandemic (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Straus, Flood, Keefe, Armstrong, Donner, Boscart, Ducharme, Silvius and Wolfson2020) and additional resources such as technological infrastructure to support person- and family-centred care (Chu, Ronquillo, et al., Reference Chu, Ronquillo, Khan, Hung and Boscart2021; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2022b). Throughout the pandemic, there have been inadequate provincial funding allocation and decision making; for example, around January 2021, the Ontario Government earmarked $42 million in funds to enable LTCHs to increase security personnel as screeners, instead of reallocating funds to support staffing capacity (Levy, Reference Levy2021). LTCHs were unprepared to manage the increased demands of the pandemic with a shortage of staff; therefore, to retain staff within the LTCHs, improvements to care workers’ wages should be made (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Straus, Flood, Keefe, Armstrong, Donner, Boscart, Ducharme, Silvius and Wolfson2020; Grabowski, Reference Grabowski2020). Although the Ontario Government took action after the first wave to address these issues – for example, in October 2020, personal support employees received an additional $3 per hour (Ontario Newsroom, 2021) – these efforts were temporary and did not provide sustainable changes to support LTCHs after the pandemic. Similarly, reactionary and temporary decision making during COVID-19 has also been seen in BC, as the province invested around $160 million to support all of BC’s LTCHs and assisted-living residences to employ three full-time staff for infection prevention and control measures (Government of British Columbia, 2020b). Additionally, EFCs were dependent upon technology to maintain connections with their loved ones in LTCHs. However, the experiences from EFCs indicated that there was a lack of technological infrastructure, Wi-Fi, devices, and staffing to support the use of the technology (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2022b). Moving forward post-pandemic, national standards of care should include a minimum staffing requirement across all LTCHs (Grabowski, Reference Grabowski2020), and drafted national standards currently suggest that Wi-Fi be part of all LTCHs across Canada (Canadian Standards Association, 2022).

Strengths and Limitations

A strength in our study is the timeliness of the topic that provides an in-depth look at the visitation experiences during COVID-19 of EFCs with LTCHs’ residents within two Canadian provinces, Ontario and BC. As with other qualitative research, the goal of this study was to enhance our understanding of the phenomenon being examined (Malterud, Reference Malterud2001). Another strength is that our study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies guidelines (See Supplement). A limitation to our study is that it included only the experiences of English-speaking EFCs; hence, the study would have been strengthened if we were able to involve a diverse set of EFCs from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds to inform our work. In addition, recruitment occurred on social media, yet interested participants were located in BC and Ontario, which both had high COVID-19 death rates (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). Nevertheless, future research should examine EFCs from other Canadian provinces and territories to explore their visitation experiences. Finally, our study originally intended to examine the residents’ experiences, but due to public health measures and the lack of staffing in the homes, we were unable to coordinate and arrange virtual interviews with residents. Despite these limitations, our findings illuminate additional paths for future research in examining caregivers’ experiences post-pandemic within Canada and internationally.

Conclusion

Our study examined the experiences of EFCs as visitation policies and modalities changed (i.e., virtual, outdoor, window) before in-person visitations resumed. The themes identified in this study highlight the issues of visitations at multiple levels (e.g., individual, home, and systems). Our study illuminates the negative impact of the COVID-19 public health and visitation guidelines on EFCs, in some cases, causing collective psychological trauma. More importantly, this study emphasizes how the deeply paternalistic policies aimed at preventing COVID-19 from entering the LTCHs failed to recognize the psychosocial needs of the residents and the EFCs, in particular the need to stay connected and maintain vital relationships. Future pandemic responses should be more patient-centred and recognize the status and value of EFCs in order to optimize the well-being of EFCs and residents and safeguard critical relationships. This includes funding the appropriate interventions and means to facilitate in-person visitations, not restricting EFCs into the homes, and LTCHs partnering with families and residents to create pandemic preparedness plans that will address their concerns and needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the 30 essential family caregivers who participated and shared their experiences.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980822000496.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: CC and VS; Focus group facilitation: CC and VS; Initial data analysis: CC and AY; Refinement and evaluation of themes: CC, AY, VS; Interpretation of results and development of the manuscript: CC and AY. All authors contributed to the reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

CC was supported by the Centre for Aging and Brain Health Innovation (grant no: 4-00279) and Bertha Rosenstadt Health Research Fund, Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto. Neither organizations played a role in the design, execution, analysis, interpretation, nor writing of the study.