CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Fear of falling is common in older emergency department (ED) patients and is associated with decreased mobility.

What did this study ask?

Is fear of falling associated with return to the ED and future falls in community-dwelling older patients following a minor trauma?

What did this study find?

Fear of falling is associated with subsequent falls at 3 and 6 months following a minor trauma.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Patients with fear of falling can be identified and oriented towards the appropriated post-ED resources to decrease the risk of bad outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization, a third of people ages ≥ 65 years fall every year, and this number increases to 50% in those over 85 years old.1 Falls remain the leading mechanism of injury-associated death, and the third leading cause of poor health among older patients.Reference Masud and Morris2

In 2018, older Canadians made 2.5 million emergency department (ED) visits,3 25% of which were the result of a fall.3,Reference Bernstein4 Our team showed that around 80% of minor injuries among older patients discharged from Canadian EDs were fall-related.Reference Sirois, Griffith and Perry5 ED-visits by older patients are considered important opportunities for preventing future falls and injuries by identifying high-risk patients.Reference Bernstein4 This appears crucial as 15% to 20% fall rates and 30% unplanned ED returns at 6 months’ post-ED visits are reported.Reference Foo, Siu, Tan, Ding and Seow6,Reference Lee, Sirois and Moore7

Fear of falling was first described as part of a post-fall syndrome in the 1980s and was considered a result of psychological distress following a fall.Reference Murphy, Dubin and Gill8 It has since been recognized as an important health issue among older adults.Reference Scheffer, Schuurmans, van Dijk, van der Hooft and de Rooij9 According to various definitions, the prevalence of fear of falling is approximately 40%–50%,Reference Lavedan, Viladrosa and Jurschik10 with wide ranges being reported from 12%–65% in community-dwelling non-fallers and from 29%–92% in seniors having already sustained falls.Reference Murphy, Dubin and Gill8,Reference Lavedan, Viladrosa and Jurschik10,Reference Murphy and Isaacs11 Fear of falling can initially be protective by increasing caution in daily activitiesReference Scheffer, van Hensbroek and van Dijk12 but could become detrimental when causing restrictions in activities and result in deconditioning.Reference Scheffer, Schuurmans, van Dijk, van der Hooft and de Rooij9 Hence, fear of falling after a fall was shown to be a significant risk factor for subsequent ED-visits for repeated fallsReference Brousseau, Dent and Hubbard13,Reference Cinarli and Koc14 and for physical, mental, and quality of life decline in older adults.Reference Provencher, Sirois and Ouellet15 The 2013 Geriatric Emergency Department Guideline recommends that every older patient presenting to the ED after a fall should undergo a comprehensive assessment of comorbidities and risk factors in order to prevent further injuries and subsequent falls.16 Since fear of falling is associated with increased risk of repeated ED visits, falls, and of declining health, identification of fear of falling through proper evaluation could be a contributing factor to older ED patient outcomes.

The main objectives of this study were to 1) characterize patients with mild, moderate, and severe fears of falling and 2) assess whether fear of falling could predict subsequent falls and returns to the ED within 6 months of the initial ED-visit for a minor injury. The secondary objective was to explore the possible association between fear of falling and specific causes of return to the ED, such as medical causes and traumatic causes.

METHODS

Study design

This is a planned secondary analysis of the Canadian Emergency and Trauma Initiative (CETI),Reference Sirois, Griffith and Perry5 a multicentre prospective cohort study (N = 3,350) conducted between 2011 and 2016 in six university-affiliated EDs (Quebec City, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Hamilton, and Calgary). Full protocol details were previously reported.3,Reference Brousseau, Dent and Hubbard13

Study setting and population

Community-dwelling older patients were included if they were ages ≥ 65, independent in all activities of daily living (ADLs) (see measures below), and presented to a participating ED with chief complaints of minor injury (i.e., not requiring admission/surgery) sustained in falls. Hospitalized patients and those unable to give consent or to speak French or English were excluded.

Eligible patients were identified by emergency physicians or research staff 24 hours/day, 7 days/week. In-person (for patients presenting to the ED during research staff office hours) or telephone interviews were conducted by trained research assistants within 72 hours of the ED visit. An in-person assessment of the participants’ physical condition (functional, mobility, and frailty status) was conducted during the in-person interview. In order to minimize loss to follow-up, the study's steering committee determined that a hybrid combination of in-person and phone interviews at 3 and 6 months would be conducted.

Study measures

Fear of falling was assessed using the Short Falls Efficacy Scale-International (SFES-I).Reference Kempen, Yardley and van Haastregt17 This validated tool assesses how concerned older adults are about falling when performing seven daily activities (getting dressed/undressed, taking a bath/shower, getting in/out of a chair, going up/down stairs, reaching for something above the head or on the ground, walking up/down a slope, going out to social events). Each component is rated from 1 (not concerned) to 4 (severe concern). Total scores range from 7 (not concerned) to 28 (most severe concern) and are interpreted by stratifying the scores into three categories: mild (7–8), moderate (9–13), and severe fear of falling (14–28).Reference Kempen, Yardley and van Haastregt17 Participants were questioned regarding any subsequent falls that might have occurred following their initial ED visit at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Participants were asked if they “had fallen hard enough to feel pain afterwards” (yes/no)18 and the number of falls they had sustained if they answered yes. Returns to the ED were also self-reported during both follow-up interviews, in which participants were asked if they had consulted to the ED (yes/no) in the past 3 months, and the number of times they did. Medical files of patients returning to the ED at Hôpital de l'Enfant-Jésus were analysed to assess the causes of return to the ED (medical or traumatic).

We collected demographic data, including age and sex. Self-reported comorbidities were recorded (yes/no) using a list of 18 physicalReference Daveluy, Pica, Audet, Courtemanche and Lapointe19 (e.g., cardiac, neurological diseases) or psychological conditions (i.e., anxiety, depression, irritability) that may have an impact on the participants’ function.Reference Daveluy, Pica, Audet, Courtemanche and Lapointe19 The Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) ED screening tool was used at the index ED-visit. ISAR ≥ 2/6 reflects needs for further geriatric evaluation.Reference McCusker, Bellavance and Cardin20 The 2005–Abbreviated Injury Scale21 codes were used to compute the Injury Severity Score (ISS), which ranges from 1 (minor) to 75 (unsurvivable).21 ISS values ≤ 8; 9–15; and ≥ 16 reflect minor, moderate, and severe trauma, respectively.21,Reference Copes, Champion and Sacco22

Patients’ functional status was measured using the validated Older Americans Resources Services (OARS) scale, which aims to assess a patient's ability to perform seven basic ADLs (eating, grooming, dressing, transferring, walking, bathing, continence) and seven instrumental ADLs (meal preparation, homemaking, shopping, using transportation, using the phone, managing medication, and money).Reference Bissett, Cusick and Lannin23,Reference McCusker, Bellavance, Cardin and Belzile24 The total OARS score ranges from 0 (dependent) to 28 (independent). Basic mobility was assessed by the Timed “Up-and-Go” (TUG), during which patients are asked to stand up, walk 3 meters away from their chairs, turn around, walk back to their chairs and sit down. The amount of time that each participant takes to perform these tasks was recorded by a research assistant. Participants’ mobility status is then considered as free (TUG < 10 seconds), mostly independent (< 20 seconds), variable (20–29 seconds), and impaired (> 30 seconds). The TUG was shown to predict functional decline in older patients with minor injuries.Reference Eagles, Perry and Sirois25 The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF)Reference Kiely, Cupples and Lipsitz26 index was used to determine frailty status of the patients. Higher SOF scores are associated with functional decline in older ED patients presenting with minor injuries.Reference Sirois, Griffith and Perry5 Cognitive impairment was evaluated in-person with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)Reference Luis, Keegan and Mullan27 or by the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m)Reference Knopman, Roberts and Geda28 with respective cut-offs of < 23/30 and ≤ 32/50 for cognitive impairments.Reference Kiely, Cupples and Lipsitz26

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics using the Student's t-test and the chi-square test (means, proportions) were used to describe patients’ characteristics according to fear of falling levels. Logistic regressions were used to examine whether fear of falling alone predicted the outcomes (yes/no) at 3 and 6 months. The risk of return to the ED and falls according to fear of falling levels were estimated using odds ratios (OR, with 95% confidence intervals [95% CI]), using mild fear of falling as the reference. Predictive statistics with 95% CI were computed (sensitivity, specificity, predictive positive value [PPV_ and negative predictive value (NPV]). Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the best (no return to the ED/fall) and worst (positive return to the ED/fall) case scenarios for the missing data. Statistical significance was defined as p-values ≤ 0.05. Data were analysed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), version 9.4.

RESULTS

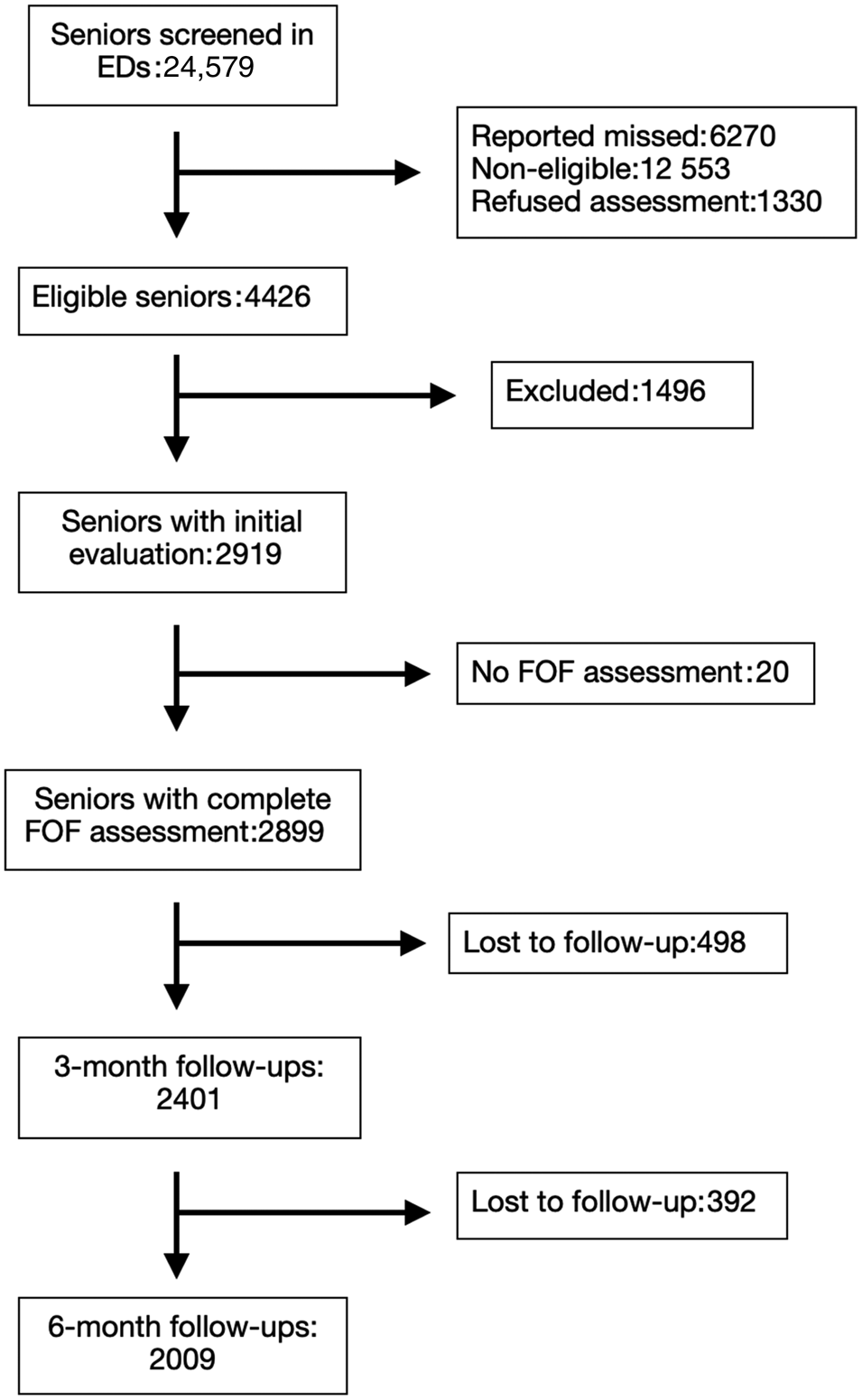

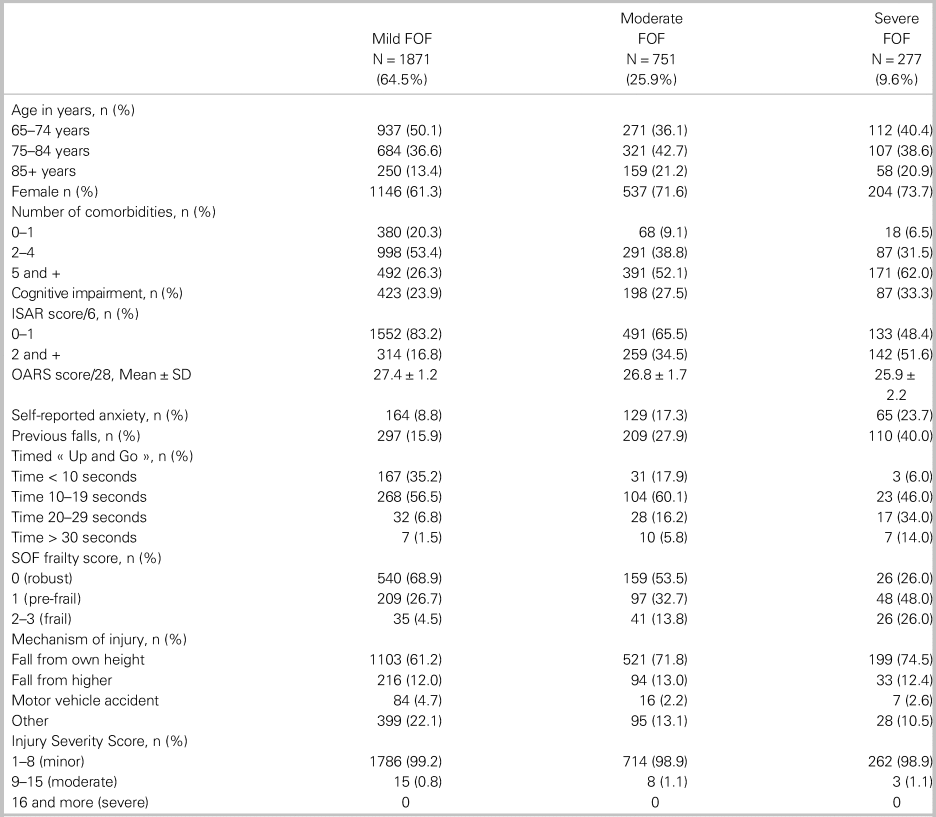

Baseline fear of falling data was available for 2,899 patients, and follow-up rates are shown in the study flow chart (Figure 1). Patients who were lost to follow-up were mostly similar to those with complete follow-ups, but a significant difference was found regarding cognitive impairment, with lost-to-follow-up patients being more cognitively impaired at baseline (see Table 1 for full details). Table 2 shows the participants’ characteristics according to fear of falling levels. Patients with moderate to severe fear of falling were older, had more comorbidities, were more cognitive impaired, and experienced more self-reported anxiety. Patients with higher fear of falling were frailer, had a slower mobility (TUG test), and a higher rate of previous falls.

Figure 1. Study flow chart.

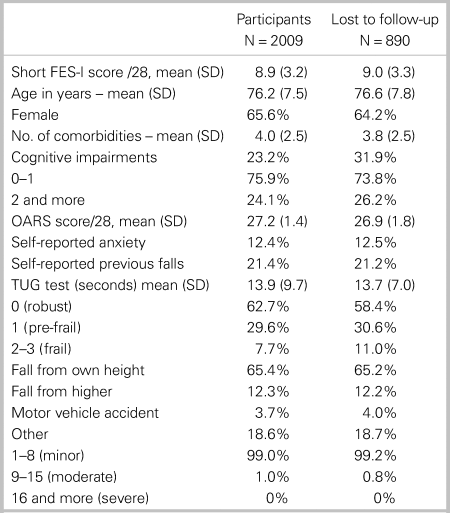

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants and those lost to follow-up

FES-I = Falls Efficacy Scale–International; ISAR = identification of seniors at risk; OARS = Older American Resources Services–functional scale; SOF = study of osteoporotic fractures; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2. Characteristics of the participants according to fear of falling (FOF) levels*

* Mild FOF = Short FES-I = 7-8/28; Moderate FOF = Short FES-I = 9-13/28; Severe FOF = 14-28/28

FES-I = Falls Efficacy Scale-International; ISAR = identification of seniors at risk; OARS = Older American Resources Services-functional scale; SOF = study of osteoporotic fractures.

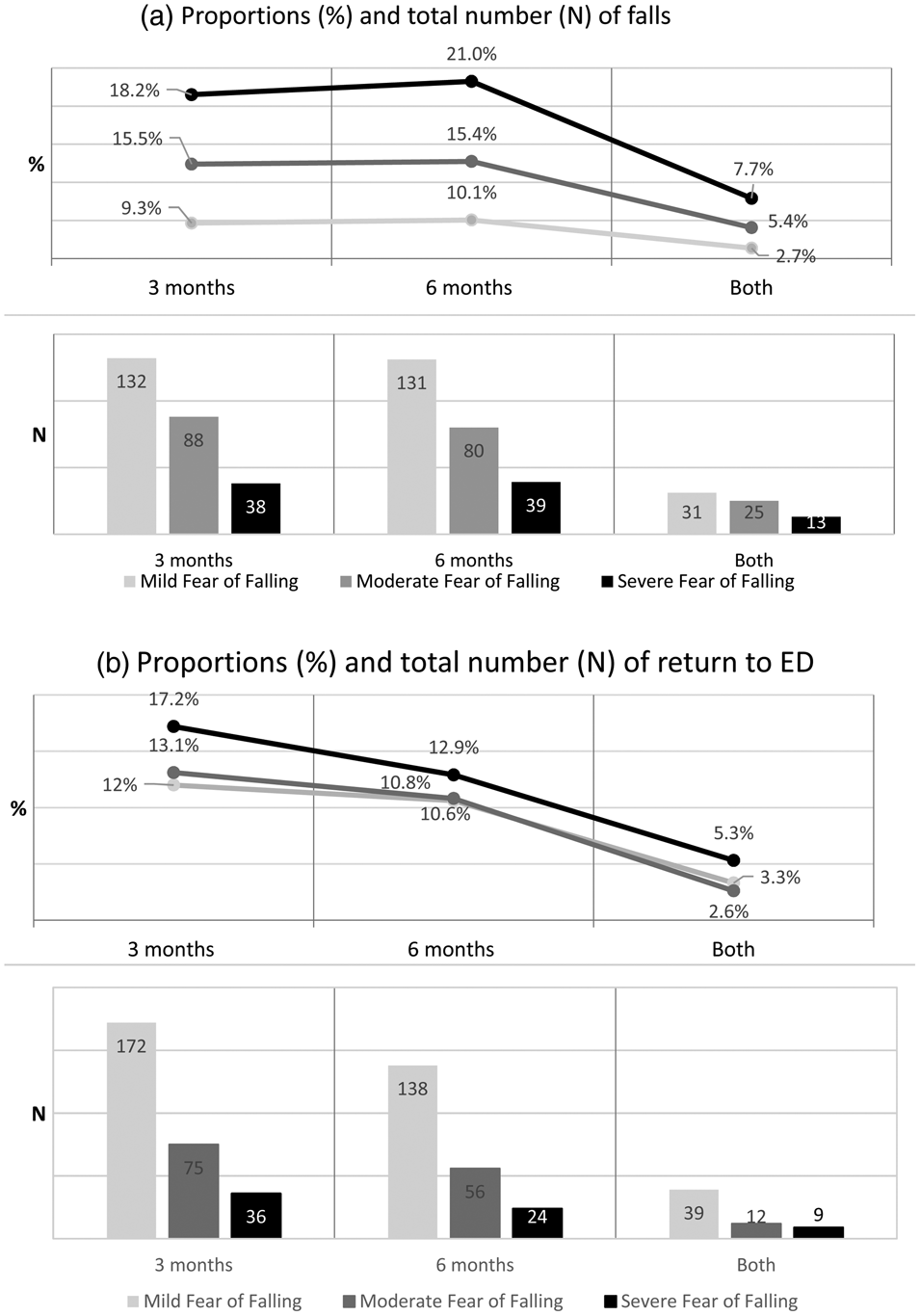

Figure 2a and 2b show the proportions and total numbers of falls and return to the ED according to fear of falling levels. While the total number of outcome events is greater in patients with mild fear of falling, the proportions of falls and return to the ED increased at 3 and 6 months with rising fear of falling levels at both time points (3-month falls in mild-fear of falling = 9.3% v. severe-fear of falling = 18.2%; 3-month return to the ED: mild-fear of falling = 12.0% v. severe fear of falling = 17.2%).

Figure 2. a) Proportion and number of patients with falls and b) unplanned return to ED at follow-up according to fear of falling levels at 3 months, 6 months, and both.

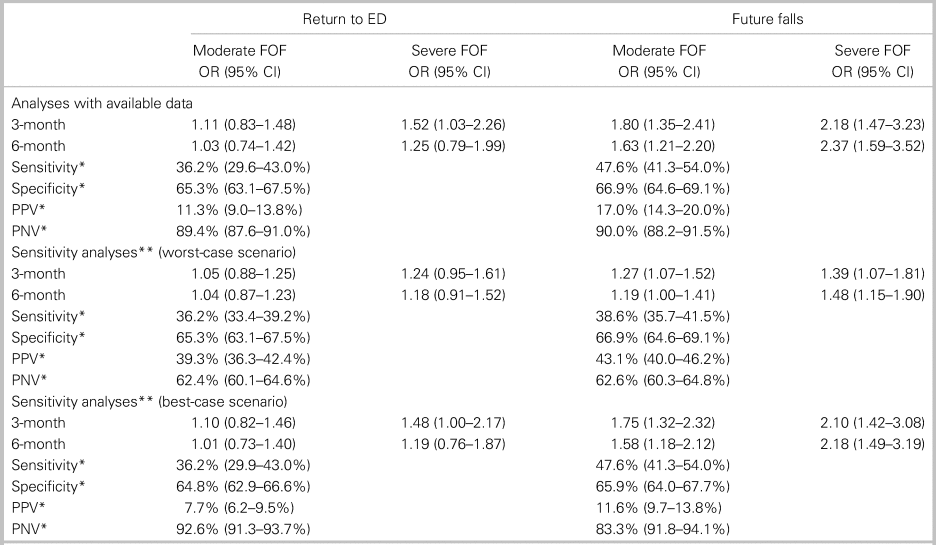

ORs were computed on the complete data set for both outcomes and time points according to fear of falling and ORs from the sensitivity analyses. Our results indicate that the risk of falls at 3 and 6 months significantly increased in both moderate (OR: 1.27 to 1.80 at 3 months, and 1.19 to 1.63 at 6 months) and severe (OR: 1.39 to 2.18 at 3 months, and 1.48 to 2.37 at 6 months) fear of falling groups. With regards to the risk of return to the ED, only severe fear of falling was associated with a significant increase of return to the ED at 3 months (OR: 1.52, p < 0.05) (full results are shown in Table 3). The predictive statistics of moderate and severe fear of falling levels considered together (v. mild fear of falling) for both outcomes at 6 months were also computed. Overall, the positive predictive capacities values of the fear of falling were low for return to the ED (sensitivity = 36.2%; PPV: 7.7% to 39.3%) and falls (sensitivity: 38.6% to 47.6%; PPV: 11.6% to 43.1%) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Estimated risk (odds ratios) for outcomes (reference: mild FOF) at 3- and 6-month follow-ups (n = 2,009)

CI = 95% confidence interval; ED = emergency department; FOF = fear of falling; PNV = predictive negative value; PPV = predictive positive value.

*Value computed according to moderate or severe FOF v. mild FOF.

**Worst-case scenario: missing data on Return to ED and Future falls were imputed with positive values; Best-case scenario: missing data on Return to ED and Future falls were imputed with negative values (RTED = no. Falls = no.)

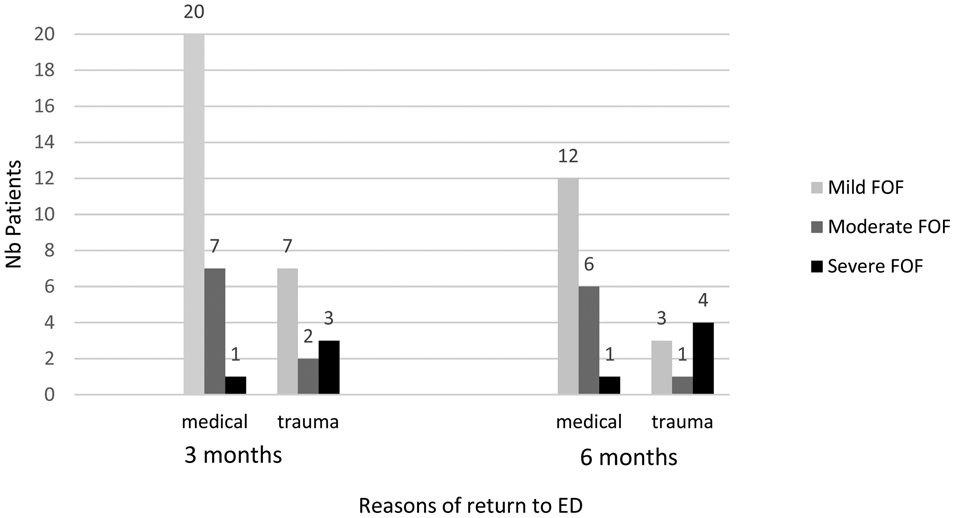

Figure 3 shows the reasons for return to the ED based on medical chart reviews in a subsample of patients (n = 71) from the study hub, the Hôpital de l'Enfant-Jésus, where 70% of return to the ED at 3 and 6 months were for medical reasons and 30% for traumatic reasons (i.e., missed injuries, delayed symptoms of concussion, etc.). Patients with mild to moderate fear of falling returned mostly for medical reasons (76.1% and 81.3% in the mild and moderate fear of falling groups, respectively), whereas 77.8% return to the ED in patients with severe fear of falling were for traumatic reasons.

Figure 3. Reasons for return to the emergency department according to fear of falling (FOF) levels at 3 and 6 months among patients from Hôpital de l'Enfant-Jésus (n = 40 patients at 3 months; n = 27 patients at 6 months).

DISCUSSION

Interpretation and previous studies

This study shows that the risk of falls within 6 months after ED-visits for minor injuries by older adults significantly rises with their increasing fear of falling levels. This is consistent with previous evidence that fear of falling is associated with future falls.Reference Friedman, Munoz, West, Rubin and Fried29,Reference Legters30 However, the significant increase in return to the ED at 3 months in severe fear of falling observed in the complete data was most likely due to the important loss to follow-up rate as it was not replicated in the sensitivity analyses. We also found that fear of falling alone tends to have poor predictive ability for both outcomes.

Overall, in our study, 12.8% and 10.9% of patients returned to EDs at 3 and 6 months, respectively. These cumulative incidences are somewhat less significant than previous reports,Reference Foo, Siu, Tan, Ding and Seow6,Reference Scheffer, Schuurmans, van Dijk, van der Hooft and de Rooij9,Reference Murphy and Isaacs11 and this could be attributed to our loss to follow-up rate. The latter could also partially explain the lack of association between fear of falling and return to the ED. This could also have been cause by our smaller number of patients with moderate or severe fear of falling, which may have been insufficient to show a difference since 64% of our cohort had a mild fear of falling. With regards to fall rates, our results concur with those of similar studies.Reference Foo, Siu, Tan, Ding and Seow6 Our overall fall rates were 11.9% and 12.5% at 3 and 6 months, respectively, and only 3.8% fell at both time-points.

Strengths and limitations

There are limitations to this study. Firstly, return to the ED and falls were self-reported. As some of our patients had cognitive impairments, their reliability to recall and declare falls or return to the ED may have been limited. Moreover, patients may underreport such events, fearing that health professionals might consider them unfit to stay in their homes. Secondly, our loss to follow-up is significant, and patients lost to follow-up had poorer cognition and were frailer. This could have underestimated negative outcomes for patients. However, as sensitivity analyses showed, the association between fear of falling and future falls is not influenced by losses to follow-up. Finally, there was no analysis on the possible medical or psychological causes for fear of falling in our patients. With regards to this issue, in the pilot study (n = 335) of the CETI cohort, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)Reference Kumar, Carpenter, Morris, Iliffe and Kendrick31 was used to evaluate patients’ anxiety and depression.Reference Sirois, Griffith and Perry5 Given that HADS scores were highly correlated with self-reported anxiety, the HADS was removed from questionnaires. Pearson's correlation was high (p < 0.0001, data not shown) between fear of falling and HADS-anxiety scores in the subset of patients with both measures.

Clinical implications

Our results could be used to improve older patient care in the ED given the high rate of fear of falling in our participants. Indeed, many correlates of increased fear of falling, such as older age, repeated falls, numerous comorbidities or medications, impaired cognition, and function in daily life,Reference Krieg, Hudon, Chouinard and Dufour32 are strong predictors of falls and of increased ED use.Reference Neufeld, Viau, Hirdes and Warry33,Reference Esbri-Victor, Huedo-Rodenas and Lopez-Utiel34 Moreover, these fear of falling correlates and fear of falling itselfReference Fillion, Sirois and Gamache35 are strongly associated with frailty, which was shown to be a strong predictor of functional declineReference Sirois, Griffith and Perry5 and of ED useReference Martel, Lauze and Agnoux36 after minor injuries in older adults. These factors can be assessed in older ED patients seeking care after a minor injury. Through their association with fear of falling, they can help physicians determine which older patients are at increased risk of returning to the ED and/or future falls. Those patients can then be oriented towards physical therapy services that can help improve their mobility and functionReference Gammon37 and decrease their level of fear of falling.Reference Robinson and Wetherell38–Reference Zigmond and Snaith40

Interestingly, the medical chart reviews showed that patients with severe fear of falling, even if a smaller number, had more returns to the ED for trauma-related reasons. Therefore, it would be reasonable to believe that if fear of falling and its correlates were assessed in the ED, emergency physicians would be able to better identify patients at higher risk of subsequent falls, such as those with a severe fear of falling, and that this would translate into a decreased rate of ED returns by community-dwelling older adults.

CONCLUSION

This multicentre study described the characteristics of older patients suffering from mild, moderate, and severe fear of falling when consulting to the ED for minor injuries. The study showed that fear of falling alone is not a strong predictive factor for returning to the ED or future falls. However, fear of falling and its correlates can be identified in older ED patients, and this information could be useful to the emergency physician when planning post-ED resources and should be part of a comprehensive fall assessment.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the emergency physicians and research assistants of all participating sites who made this project possible. This article received the following: Resident Abstract Award, CAEP 2019 (Halifax); AMUQ 2019 Poster Competition, 2nd place (Montréal); CIHR team grant top 6 projects, 2019.