Introduction

The trade in wildlife involves many thousands of species and millions of specimens each year and nowhere is this having a more devastating impact than South-East Asia, where an increasing number of species are being pushed closer to the brink of extinction owing to illegal and unsustainable trade (Nijman Reference Nijman2009). Addressing these threats is widely acknowledged to be one of the highest conservation priorities for the region (McNeely et al. Reference McNeely, Kapoor-Vijay, Olsvig-Whittaker, Sheikh and Smith2009, Nijman Reference Nijman2009, Duckworth et al. Reference Duckworth, Batters, Belant, Bennett, Brunner, Burton, Challender, Cowling, Duplaix, Harris, Hedges, Long, Mahood, McGowan, McShea, Oliver, Perkin, Rawson, Shepherd, Stuart, Talukdar, van Dijk, Vié, Walston, Whitten and Wirth2012).

The Helmeted Hornbill Rhinoplax vigil, the largest of Asia’s hornbill species, occurs in primary semi-evergreen and evergreen lowland forest in Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia (Kalimantan and Sumatra), Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand. As one of eight hornbill species native to Borneo, it is important in the culture of many ethnic groups on the island (e.g. Schuyler Reference Schuyler1950, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Nyaoi and Sompud1997), was sometimes associated with head-hunting and the afterlife (Kinnaird and O’Brien Reference Kinnaird and O’Brien2007), and is the state bird of Indonesia’s West Kalimantan province. Its skull makes up around 11% of the weight of the bird (Kemp Reference Kemp1995), with the casque particularly pronounced in comparison to that of other hornbill species. At just 8×5×2.5 cm (Espinoza and Mann Reference Espinoza and Mann1999), the casque provides a relatively small piece of ‘ivory’, but in the hands of a skilled artisan it can be intricately carved. Hornbill ivory is creamy-white or yellowish-orange in colour with a bright red edge. The Indonesian name for the Helmeted Hornbill, Enggang gading, translates as ‘ivory hornbill’.

Traditional use of the Helmeted Hornbill in Borneo focused largely on carved casques in some local costumes (Schuyler Reference Schuyler1950) and tail feathers for use in cultural dancing (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Nyaoi and Sompud1997). The first mention of hornbill ivory in international trade dates back to 1371 when a quantity was sent with other tribute gifts to the Ming Court in China from the Boni court in Borneo (Kurz Reference Kurz2014). Around this time, the value of one piece of hornbill ivory was said to be around four times the cost of 1 kg of elephant ivory (Schuyler Reference Schuyler1950). In Palembang, Sumatra, Chinese reports dating from 1416 indicate the presence of a sizeable industry producing swords decorated with hornbill ivory, a use which was recorded a century later in what is now Myanmar (Schuyler Reference Schuyler1950). There are also early reports of the sale of Helmeted Hornbill heads from Myanmar to Thailand for carving in the late 1800s, with prices at the time quoted as being equivalent to US$ 20 per head. Initially carved into belts in China, its use changed over time towards the production of decorative items such as snuff bottles in China and later in Japan; and as time progressed, the casque came to be used for jewellery, some of it for Western markets (Schuyler Reference Schuyler1950).

Over recent years, records of enforcement activity and information collected on the ground in the forests of Indonesian Borneo and Sumatra show that trade in, and demand for, the Helmeted Hornbill has become significant. Monitoring of trade in the species in China, conducted by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA 2015a), shows that the sale of Helmeted Hornbills is often facilitated online, with researchers noting a recent addition to the codes used in discussions about commerce in illegal wildlife, with ‘red’ for hornbill ivory now joining ‘black’ for rhinoceros horn and ‘white’ for elephant ivory. The trade and production of finished items in ‘red’ are conducted through the same facilities used for ‘black’ and ‘white’ (EIA 2015a).

The Helmeted Hornbill has been listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1975. Commercial international trade in the species, including its parts and derivatives, is therefore not permitted. The species is afforded protection under the national legislation of all countries in which it is found. In 2015, partly in response to the evidence in the present paper in draft, its international IUCN Red List status was changed from ‘Near Threatened’ to ‘Critically Endangered’, justified by the expectation that populations will experience an extremely rapid and severe decline over the next three generations, with poaching and illegal trade listed as a leading threat (BirdLife International 2015).

The aim of this study was to compile data on recent seizures of Helmeted Hornbills or their body parts in order to make a first assessment of the numbers currently occurring in the illegal trade across Asia, in order to assist in guiding future conservation and enforcement efforts.

Methods

We searched for and compiled all available records of trade and seizures of Helmeted Hornbills and their parts and derivatives in the 18 months between March 2012 and August 2014. These were taken from published accounts in the form of government documents and media reports, as well as from individuals and organisations working in both source and demand areas. (It should be noted that seizure records alone provide little or no indication of when the seized animals were removed from the wild.) Further, anecdotal information and observations on trends in trade and hunting were gathered from relevant researchers living and working in the region.

Information was also collected from the CITES trade database up until 2014. All countries which are party to CITES are required to submit an annual report to its secretariat detailing all international trade in species listed on the Convention’s appendices. These are compiled in a database now containing over fifteen million trade records. The figures submitted by importing countries should match those provided by exporting Parties, but in practice discrepancies between these are common. Whilst CITES Parties are encouraged to record seizures in their data, very few choose to do this.

Results

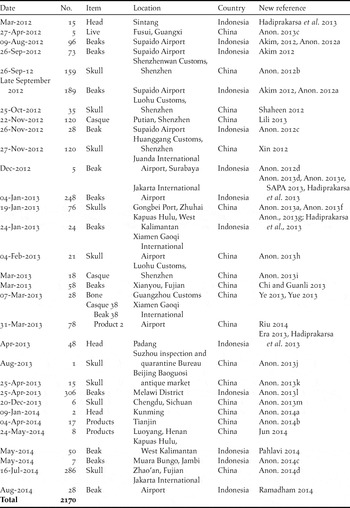

Between March 2012 and August 2014 a minimum of 2,170 Helmeted Hornbill heads and/or casques were seized from the illegal trade in 31 identifiable enforcement actions at 24 separate locations (Table 1). Of these, 1,117 specimens, variously described as beaks, bills, heads and ivory (average 86 per seizure; smallest five, largest 306) and representing more than 50% of the total number confiscated, were seized in 13 enforcement actions at eight Indonesian locations.

Table 1. Seizures and numbers of Helmeted Hornbill seized between March 2012 and August 2014 (excluding results from Operation Cobra).

*Note: – bills and beaks are considered the same, and it is assumed that these all include casques, as do heads

Within our study period, between 6 January and 5 February 2013, a multinational attack on the activities of wildlife criminals entitled Operation Cobra seized large quantities of illegally traded wildlife, including at least 324 Helmeted Hornbill beaks (Anon. 2013b). However, since 203 of these beaks could not be assigned to any particular event or location, they are excluded from Table 1 for fear of duplication.

Indonesia

Between March 2012 and August 2014, 781 Helmeted Hornbill heads and/or casques were confiscated in eight seizures in West Kalimantan, representing close to 70% of the total seizures made in Indonesia. Four seizures were made at Supaido International Airport, Pontianak (the provincial capital) (386 specimens), two in Kapuas Hulu (24 and 50 specimens) and one each in Sintang (15) and Melawi District (306). The second largest seizure in Indonesia in this period (248 beaks in the luggage of four Chinese nationals en route to Hong Kong), although made at the Soekarno–Hatta International Airport in Jakarta, was suspected to have involved specimens originating in Kalimantan (Anon. 2013d, SAPA 2013).

In December 2014, the West Kalimantan Regional Office for the Conservation of Natural Resources Centre (Balai Konservasi Sumber Daya Alam―BKSDA) announced that it had destroyed a range of wildlife parts seized between 2012 and 2014, including over 229 Helmeted Hornbill parts (Anon. 2014f). These represent less than 30% of the total Helmeted Hornbill products seized in this province. The remaining 552 parts are presumably still in storage.

Just two seizures were reported from Sumatra, the first (involving 48 heads) in Padang, capital of West Sumatra province, in April 2013, the second (involving seven beaks) in Jambi province in May 2014. In July 2013, enforcement teams carried out surveillance and arrested nine men under suspicion of poaching Helmeted Hornbills in a national park in Jambi province; however, although their high-powered airguns were confiscated, the men were eventually released with a formal warning after it became clear that the casques had already been smuggled out of the forest the day before (Martyr Reference Martyr2014).

Just three seizures were recorded in Java. Two, comprising 28 and 248 beaks respectively, were made at Jakarta International Airport, and the third, consisting of five beaks, at Surabaya International Airport.

Malaysia, Thailand and Myanmar

No seizure records were found for Malaysia, Thailand or Myanmar in the period under review. However, in January 2014 TRAFFIC researchers recorded four carved Helmeted Hornbill casques during a survey of the Mong La market on the Myanmar–China border. Numerous surveys of border markets in Myanmar have been conducted by TRAFFIC over the past 15 years, and while the heads of Oriental Pied Hornbills Anthracoceros albirostris, Wreathed Hornbills Rhyticeros undulatus and Great Hornbills Buceros bicornis have been observed on a number of occasions, this was the first time that Helmeted Hornbills were recorded.

China

We found records of 18 Chinese seizures between April 2012 and July 2014 involving 1,053 Helmeted Hornbill specimens (five listed as alive, the rest described as skulls, heads, casques, products and bone; average 59 specimens per seizure). Seizures took place in 11 locations, most in eastern coastal areas but including large cities further inland such as Beijing, Chengdu and Kunming. Whilst most seizures involved specimens in transit to other parts of the country, some were made at other points in the trade chain including 58 beaks seized from a carving factory in Fujian province (Chi and Guanli Reference Chi and Guanli2013) and 15 found at a Beijing antique market (Anon. 2013k). In some cases, other illegal wildlife items including tiger skins and elephant ivory (and on one occasion large quantities of cash) were also seized (Anon. 2013k). In August 2014, the Chinese authorities arrested two men suspected of running a network which used a mobile phone networking app to advertise a range of protected species, including Helmeted Hornbills, to buyers from more than 20 locations throughout China (Anon. 2014e).

CITES trade database

Under the terms of the CITES convention, commercial trade is not permitted for Appendix I- listed species such as the Helmeted Hornbill. The database nonetheless lists 41 records submitted by importing countries amounting to 196 Helmeted Hornbill specimens since 1978. These include two imports totalling 103 feathers sent from Malaysia to Australia and New Zealand. Thirty-two records totalling 80 items variously described as carvings, horn (carvings, products and pieces), skulls and trophies were reported by importing countries. Seventeen trades, reported by exporting countries, are described as ‘pre-convention’ (meaning that the specimen pre-dates CITES restrictions). Nine records totalling 40 specimens are recorded with the source code ‘I’ by importing countries, indicating that they were confiscated or seized. Eight were reported by the USA and described as skulls, carvings and horn carvings, the most recent of which took place in 2011. The remaining seizure, involving 20 skulls, was made by China in 2000.

Despite the restrictions in place for species listed on Appendix I, 19 records of commercial trade involving 38 specimens were submitted by importing countries. Of these, 11 specimens are described as pre-convention and just one was seized.

Discussion

The quantities of Helmeted Hornbills reported on the CITES trade database from 1978 to 2013 represent just a small fraction of those uncovered through this analysis of seizures between March 2012 and August 2014. One explanation for this must be that the current levels of trade in hornbill ivory represent a very recent surge, a view supported by observers in Borneo in the mid-twentieth century, who testified to the actual or virtual absence of any trade (Collar Reference Collar2015).

However, this newly intensifying persecution of Helmeted Hornbills occurs alongside much longer-established commerce in other threatened species. The four Chinese nationals arrested at Jakarta International Airport at the start of 2013 were also carrying significant quantities of pangolin skins (Anon. 2013d), and in China tiger skins and elephant ivory have been seized with Helmeted Hornbills (2014a). In 2014 a Chinese actress was investigated and later arrested for the illegal trade of two Helmeted Hornbill heads, in addition to over 1,200 other items including rhino horn and elephant ivory (Anon. 2015).

Other evidence indicates that all this trade is in the hands of organised criminal gangs. In early 2013, following reports of a surge in Helmeted Hornbill trade in Sumatra, investigations by Flora & Fauna International (FFI) showed that the trade in Kerinci Seblat National Park (KSNP), Sumatra’s largest protected area, is highly organised, with crime syndicates based in eastern Sumatra operating networks of (and even supplying snares and firearms to) poachers and local traders, who also target Sumatran Tigers Panthera tigris sumatrae and Sunda Pangolins Manis javanica (Martyr Reference Martyr2014). Three Helmeted Hornbill poachers arrested by KSNP staff in May 2014 identified other members of their syndicate from camera trap photographs taken in the park, and revealed that this syndicate, operating out of West Sumatra, was commissioning the poaching of Helmeted Hornbills in three Sumatran provinces and supplying the casques to buyers in Riau province (D. M. unpubl. data). Investigators working in North Sumatra and the Gunung Leuser ecosystem, which straddles North Sumatra and Aceh, have indicated that similar activities are occurring in these locations (D. M. unpubl. data), while in West Kalimantan investigations in 2013 determined that 2–5 poaching teams were operating in each of five study areas and that each team made 1–3 hunting trips each month and generally poached 10–30 hornbills per trip, usually locating the birds at fruiting fig trees (Hadiprakarsa et al. Reference Hadiprakarsa, Irawan and Adhiasto2013).

Multiplication of these latter figures indicates that in recent years poaching gangs in West Kalimantan were removing between 1,200 and 27,000 Helmeted Hornbills per year. Although the upper limit appears highly improbable, it should nonetheless be noted that even the lower limit greatly exceeds the level of harvest (one bird per 84.2 km2) regarded as sustainable in Malaysian Sarawak (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Nyaoi and Sompud1997) and neither limit accounts for dependent chicks, which are certain to perish if the provisioning male parent is killed, or for self-incarcerated nesting females, which may not survive the death of their partner and are certainly unlikely to breed again for years if they do (Collar Reference Collar2015).

Unsurprisingly, anecdotal reports suggest that Helmeted Hornbills, which have distinctive, far-carrying vocalisations, are now rarely heard in the forests of Sumatra (J. Eaton, M. Slothouwer pers. comm.) and West and Central Kalimantan (Y. H. pers. obs.). Additional reports suggest that this decline also extends to other large hornbill species, perhaps as a result of indiscriminate hunting by poachers ignorant of market demand (G. Usher pers. comm., D. M. pers. obs.). In good habitat in the absence of persecution the population density of the species has been estimated between 0.7 individuals per km2 in Barito Ulu, Central Kalimantan (McConkey and Chivers Reference McConky and Chivers2004) and 1.21 individuals per km2 in southern Thailand (Gale and Thongaree Reference Gale and Thongaree2006), but such values seem unlikely to apply now.

Meanwhile the price of Helmeted Hornbill products is reportedly five times that paid for ivory on a weight basis (EIA 2015a) and a single casque can fetch around US$ 1,000 (Hughes Reference Hughes2015). Thus the value of the 2,170 Helmeted Hornbill items seized in Indonesia and China is likely to exceed US$ 2 million, suggesting that the rush to supply demand will continue. At present, the focus of poaching efforts appears to be on Indonesian populations, but the 2015 IUCN Red List assessment suggests that this is likely to shift to Malaysia as the birds become harder to find (BirdLife International 2015). The presence of the four carved specimens observed at the Mong La market in Myanmar indicates that trade in the species is already occurring outside of Indonesia. Links exist between traders in Mong La and suppliers in Fujian province, with carved casques being smuggled into the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone in Bokeo Province in Lao PDR (EIA 2015b).

The action of enforcement agencies in making multiple seizures is to be applauded. However, while announcements of seizures help publicise the trade, little coverage is given to subsequent legal proceedings. Publication of seizure news often includes the value of the items found, and when this occurs without mention of possible penalties (e.g. Bider Reference Bider2012, Anon. 2013e, EIA 2015a) there is a risk that this may increase involvement in the trade. If laws are to be effective and act as a deterrent, publicity surrounding seizures should emphasise the consequences of offending rather than the money to be made out of doing so, as in the case of a passenger arriving at Gongbei Port, a major link between Macau and Guangdong, in January 2013, whose suitcase was found to contain 76 Helmeted Hornbill skulls and who was later fined RMB 20,000 (US$ 3,257) and sentenced to five years in prison (Anon. 2013a).

The urgent action needed if the Helmeted Hornbill is to persist in South-East Asia’s forests should extend far beyond an increase in enforcement efforts against poachers. Whilst it is vital that on-the-ground patrolling and monitoring is stepped up, robust and far-reaching investigations are necessary if the organised criminal networks which coordinate the trade in this and other threatened species are to be dismantled. In particular, continued and increased vigilance is required in China and Indonesia. Since most of the specimens seized have been found in the airports of Kalimantan and Jakarta, special attention should be paid to these vulnerable locations along the trade chain. Arrests of poachers, low-level middlemen and couriers occur frequently across South-East Asia, but rarely result in punishment of or even minor inconvenience to those who coordinate the activities of such people. Consumers, too, need to be alerted to the illegality of trade and their need to shun products said to be made of hornbill ivory.

Meanwhile, although existing information suggests that the trade in the Helmeted Hornbill is a major concern, data are needed to determine the extent of population declines and habitat loss. The lowland forests inhabited by the species have high commercial value and remain at serious risk from forest fires, agriculture, mining, infrastructure development and illegal logging. They are being lost at higher relative rates in South-East Asia than in other tropical regions (Sodhi et al. Reference Sodhi, Koh, Brook and Ng2004). Recent assessments of forest loss by remote sensing suggest that 12% of forest was lost from within the species’s range between 2000 and 2012 (Tracewski et al. in prep.). Increased enforcement and documentation of the species’s decline will be of little practical value if its habitat is not also afforded effective and sustained protection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of those who provided information and assistance, including Xu Yao and Yanyan Guo from TRAFFIC in China, Eric Schnittke of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Graham Usher, Tom Clements, WCS-Indonesia Programme, Marten Slothouwer, James Eaton, Richard Thomas, Boyd Leupen and Nigel Collar. YH thanks the Chester Zoo Conservation Research Funding Support for the 2012–2013 investigation, and TITIAN Foundation. CRS thanks Wildlife Reserves Singapore for their generous funding support.