“I didn’t have maternity leave. I had a meeting a week after giving birth. I taught a week and a half after giving birth. It was incredibly difficult.”

A singular question motivates our research: Why do women leave academia before they have a chance to advance through the ranks? The answers point to lower-order processes that are uncomfortable to discuss but that contribute to well-documented higher-order outcomes, such as fewer publications, lower-status academic appointments, and leaving the profession altogether. The “leaky-pipeline” metaphor speaks to this phenomenon wherein women achieve tenure and promotion at lower rates than men, creating a shortage of role models and mentors and perpetuating norms and policies that unduly burden women (Hancock, Baum, and Breuning Reference Hancock, Baum and Breuning2013). In November 2017, we deployed a 100-question survey on gendered aspects of family formation; more than 300 respondents answered in full.Footnote 1 Respondents helped us to clarify how two types of biases affect women’s academic careers: (1) subtle lower-order processes (i.e., daily experiences and decisions) that manifest in (2) overt higher-order phenomena (i.e., trends seen in particular disciplines or the profession as a whole) that can be more easily captured empirically.

The problem actually is about gender because some men who assume the “primary-parent” role are similarly penalized. Women overwhelmingly bear the brunt of professional setbacks in academia: having children boosts men’s careers while hindering women’s (Ginther and Hayes Reference Ginther and Hayes2003; Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012). Our survey respondents described the tradeoffs and decisions that lead academic parents to persist in or exit the academic pipeline. The main takeaway is this: Having children amplifies and intensifies all of the obstacles that female scholars already face in academia. Academics in gender-nonconforming parenting roles also report difficulties, penalties, and isolation. Our research goes beyond the usual focus in the literature about the “mom penalty” and the effects of parenting and household responsibilities on women while also recognizing the disproportionate burden they carry.

Lower-order processes connect to higher-order processes—affirming the leaky-pipeline problem—in the following way: policies designed to protect women’s careers are routinely ignored or applied inequitably, and the social and familial “buffers” that bolster new parents are often absent. Academic women lack an institutional or social safety net. Survey respondents report being denied basic, legally mandated accommodations related to family formation and expending political capital in their department and college, bargaining for established policies to be upheld. Women tend to suffer professionally more than men whose careers, by comparison, benefit from parenthood in well-documented ways—notable exceptions notwithstanding (Antecol, Bedard, and Stearns Reference Antecol, Bedard and Stearns2016; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2015). Women are advised to simultaneously “lean in” (Sandberg Reference Sandberg2013) and realize that we cannot have it all (Slaughter Reference Slaughter2015). Thus, lower-order processes such as the physical and mental health consequences of “leaning in” without adequate support systems are contributing to women’s decisions to leave the profession. To address the inequalities at the top, we must acknowledge the problems at the foundation.

Thus, lower-order processes such as the physical and mental health consequences of “leaning in” without adequate support systems are contributing to women’s decisions to leave the profession. To address the inequalities at the top, we must acknowledge the problems at the foundation.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The next section discusses the well-documented higher-order phenomena before turning to the less frequently observed lower-order processes and our survey work. We conclude with a list of best practices and advice cultivated from our survey responses.

HIGHER-ORDER PROCESSES

We refer to the observable, well-documented gender gaps in the academy that create obstacles to women’s advancement as higher-order processes. These include outcomes such as disparity in rank attainments, salaries, service obligations, and publication records (Breuning and Sanders Reference Breuning and Sanders2007; Clark Blickenstaff Reference Clark Blickenstaff2005; Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012; Mitchell and Hesli Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013; The London School of Economics and Political Science 2014; Voeten Reference Voeten2013). Other factors contributing to the leaky pipeline include hiring discrimination; bias in teaching evaluations; unequal career benefits of taking parental leave (Antecol, Bedard, and Stearns Reference Antecol, Bedard and Stearns2016; Wolfers Reference Wolfers2017); contending with the “two or more body” problem that couples with children face (Wolf-Wendel, Twombly, and Rice Reference Wolf-Wendel, Twombly and Rice2004); and gender gaps in citations (Eidinger Reference Eidinger2017; Wolfinger, Mason, and Goulden Reference Wolfinger, Mason and Goulden2009). Given societal expectations about family responsibilities, it is impractical to decouple gender dynamics from those surrounding parenthood.

Systemic bias against family formation in academia continues to penalize early-career scholars and those not on the tenure track who have children or are in the process of becoming parents (McGlen and Sarkees Reference McGlen and Sarkees1988). The timing of the tenure probationary period frequently (but not always) coincides with the years in which early-career scholars are contemplating family commitments, including the decision to have children (Armenti Reference Armenti2004). Research by Mason, Wolfinger, and Goulden (Reference Mason, Wolfinger and Goulden2013) found that only 58% of early-career mothers earned tenure, whereas 78% of early-career fathers did. Women are less likely to achieve the rank of associate professor and the accompanying benefit of tenure. However, those who do “are as likely as men (given relevant controls) to move up the academic ladder to full professor” (Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012). The evidence is mixed about whether partnership/marital status or number of children affects promotion (Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012). For instance, men enjoy a professional boost from “marriage to a spouse without a professional degree” (Morrison, Rudd, and Nerad Reference Morrison, Rudd and Nerad2011), while noting that “women with heavy family responsibilities may have already left academia” (Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012; Morrison, Rudd, and Nerad Reference Morrison, Rudd and Nerad2011). In dual-academic couples, women often take non-tenure-track positions as the “trailing spouse,” with fewer professional resources (Bender and Heywood Reference Bender and Heywood2006).

Foschi (Reference Foschi1996) offered a damning indictment of implicit bias against women in general: they must outpace men in their publications to persuade tenure and promotion committees of their commitment to scholarship. Once published, female-authored research is less likely to receive recognition. The gender citation gap favors white-male-identified scholars over female scholars and scholars from marginalized groups (Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Mitchell, Lange, and Brus Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brus2013; Sabaratnam Reference Sabaratnam2017). Women also are penalized for flouting gender norms when they bargain for better salaries or benefits (Tinsley et al. Reference Tinsley, Cheldelin, Schneider and Amanatullah2009), so it is not surprising that they “don’t ask” for more (Mitchell and Hesli Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013). When family-leave policies are inequitably applied, women bargain to receive the bare minimum required by law, leaving little room for bargaining elsewhere. In summary, academia already is biased against women before accounting for the realities of parenthood.

LOWER-ORDER PROCESSES

We refer to the day-to-day factors that accumulate and create leaks in the pipeline—including stress, health, well-being, relationships, household management, pregnancy and infertility, childcare, and other myriad personal and familial opportunities and challenges—as lower-order processes. Academic women experience infertility and fertility treatments, convoluted adoption processes, miscarriages (Winegar Reference Winegar2016) and infant loss (Stein Reference Stein2013), complicated pregnancies, undiagnosed and unsupported postpartum depression and anxiety, and sleeplessness and sickness in the daycare years. Childcare requires navigating unaligned university and daycare or school calendars, inclement-weather days, sick days, and meetings scheduled during times when childcare is not available. Parents’ physical health suffers during their children’s early years because shared illnesses compound the effects of sleep deprivation. These scenarios lead to reduced productivity that disproportionately affect women’s careers.

These realities contribute to a toxic work environment for women and parents that make it difficult for them to stay in the profession (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Gunn, Kaplan, Raj and Freund2015) and exacerbate existing well-documented inequalities in academia (Morrow Jones and Box-Steffensmeier Reference Morrow Jones and Box-Steffensmeier2014; Staats Reference Staats2013). Administrators and successful scholars should care about the daily realties of academic parents because institutions that fail to support “work–life balance” risk losing female faculty to stress-induced burnout via departure to another institution or from academia altogether (Gardner Reference Gardner2012). As one respondent said about having a less-than-supportive academic environment: “They don’t care. They just want results. If I fail, it is no skin off their nose because I am replaceable. They don’t need to offer any support.” Improving diversity at all levels and retaining and promoting women—especially minority women—in academic disciplines (Arnett Reference Arnett2015) requires serious reconsideration of institutional, college-level, and departmental policies related to family formation (Pirtle Reference Pirtle2018).

SURVEY INSIGHTS ON GENDER, BIAS, AND FAMILIES

Most of our survey respondents (85%) identified as female and their households had either one (46%) or two (38%) children; slightly more than 10% had three or more children. Tenure-track-faculty respondents had, on average, 1.5 children whereas non-tenure-track faculty respondents had 1.4. Of all respondents, 10% earned tenure before having their first child—a finding that stands in stark contrast to much of the informal advice given to early-career female scholars: Wait until after tenure to have children.

Of all respondents, 10% earned tenure before having their first child—a finding that stands in stark contrast to much of the informal advice given to early-career female scholars: Wait until after tenure to have children.

Academics who face conflicts between family commitments and the job search or the tenure track may decide to accept lower-ranked positions (e.g., adjuncts, instructors, and visiting assistant professors). Although this approach may help female scholars “stay in the game” (Wolfinger, Mason, and Goulden Reference Wolfinger, Mason and Goulden2009), the non-tenure-track contingent lacks privileges and protections, such as access to family leave and extending a tenure clock, while also carrying a heavier teaching load and netting a lower salary (Mason, Wolfinger, and Goulden Reference Mason, Wolfinger and Goulden2013). Figure 1 shows that 25% of respondents had such precarious employment; this concurs with the American Political Science Association (2015) survey on academic placement in which 25% of women (versus 19% of men) accepted non-tenure-track positions.

Figure 1 What Is Your Current Professional Employment? (N=216)

FAMILY-LEAVE POLICIES ARE NOT TRANSPARENT, CONSISTENT, OR EQUITABLE

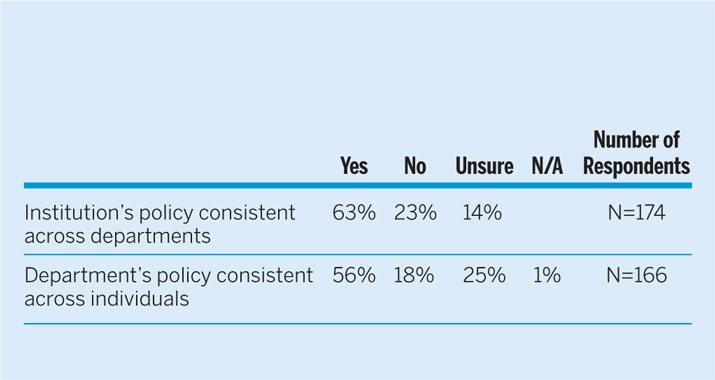

Family-leave policies are insufficient and poorly communicated: some parents must use their accrued sick leave, which unfairly penalizes women who primarily access FMLA provisions, whereas men accrue sick leave over time; other parents lack leave options altogether (e.g., newly hired faculty). As shown in table 1, one third of respondents reported that policies are applied inconsistently across departments or that they were unsure whether they are. Almost one fifth of respondents stated that policies are applied inequitably across individuals and fully one quarter were unsure. This signals a gaping policy chasm: there is an obvious need for family-leave policies to be clearly articulated to ensure that they are fairly applied. For respondents who negotiated family leave, 33% negotiated for reduced teaching, 33% for an altered schedule, 7% for tenure-clock changes, and 10% for official leave. Yet, 15% of respondents stated that their chair, dean, or other administrator refused to negotiate with them. This failure to accommodate family leave is strikingly common. According to one respondent, “I asked if I could have some time off and they said no.” Another said, “I tried, but ran into a lot of brick walls. I spoke with the division head and with the vice-president/provost, and the latter insisted that maternity leave was only for women giving birth (which was treated as an illness!) and did not include adoptive parents.” Yet another respondent raised several issues: “For my first child, I was a graduate student and so did not negotiate any leave. For my second/third child (twins), I was a faculty member and *attempted* to negotiate leave, but was not granted leave.”

Table 1 Equitable Policy Implementation

Source: Survey

When family-leave policies are communicated inconsistently and applied institutionally, women bear the burden individually of figuring out how to balance their work and family commitments, which adds additional stress and contributes to burnout. Women may try to time pregnancies to give birth during university breaks to avoid inconveniencing their department, sacrificing time that their academic male counterparts can devote to research or relaxation. One respondent recalled: “As an adjunct, I was physically in-class two weeks after giving birth. I was also responsible for interacting with confused students as to why I wasn’t in class the first two weeks and instead had online assignments. (I answered many of these questions via email on a laptop in the hospital or dictated emails to my husband.)”

We emphasize that inequitable service assignments and inadequate family-leave policies are linked, and both compound the strain that erodes health, well-being, and ability to manage competing work and life demands. Some administrators compensate for inadequate family-leave policies with reduced teaching and research responsibilities—while assigning low-visibility and low-prestige service work (Mitchell and Hesli Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013; Murdie Reference Murdie2017)—providing “care of the academic family” (Guarino and Borden Reference Guarino and Borden2017). One respondent said, “Mothers in my department get one semester off from teaching and are assigned service activities to ‘compensate’ for the four-week difference between the 12 weeks of FMLA and the 16-week semester. Fathers do not take leave. This varies by department, both in terms of amount of time off and amount of pay received during leave.” Another respondent said she could not take maternity leave without losing health insurance; service assignments kept her covered. Women are expected to take on more service responsibilities; when they fail to exceed the unequal expectations placed on them, they encounter additional bias.

Furthermore, unequal service assignments amplify gender, racial, and family-status biases in academia, underscoring the need to address intersectionality around family formation (Bellas and Toutkoushian Reference Bellas and Toutkoushian1999). Pirtle (Reference Pirtle2018) summarized this point as follows:

For instance, the year after my son was born, in the third year of my PhD program…I was replaced on projects I had previously worked on and wasn’t invited to join others. I couldn’t afford the money and time needed to travel to as many conferences. Even though I took no time off, enrolled my son in day care, and spent most days on campus working to meet deadlines, I was told that I wasn’t serious about my research. I was instructed to be more like the white male graduate student a cohort below me whose wife had had a baby, advice that erased the many status differences between us.

Transparency is essential. Women hesitate to aggressively negotiate accommodations for fear of professional retribution, a well-founded concern affirmed by scientific studies of gender and negotiations (Bowles, Babcock, and Lai Reference Bowles, Babcock and Lai2007). A “one-size-fits-all” approach will not meet everyone’s individual needs; however, family-leave accommodations should not be idiosyncratic or dependent on an individual’s willingness to negotiate. Clear and equitable family-leave policies should be the “ground floor” for universities. Culture change is needed: universities should provide accommodations above and beyond the bare minimum, in accordance with the spirit of recommendations from other areas of gender discrimination (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine 2018).

Clear and equitable family-leave policies should be the “ground floor” for universities. Culture change is needed: universities should provide accommodations above and beyond the bare minimum...

TOWARD BETTER, FAIRER, AND MORE CONSISTENTLY APPLIED POLICIES

We asked our survey participants to share the best advice they had given or received (figure 2) and their recommendations for policies and practices that mitigate family-formation bias (figure 3). These recommendations are illustrative, not exhaustive.

Figure 2 Advice from Survey Participants

Figure 3 Advice for Negotiating

Discrimination against women and parents is rooted in the concern of whether they are likely to be awarded tenure. Women are accused of not taking their careers seriously if they choose to have or adopt children pre-tenure. Mentoring programs including Journeys in World Politics, Visions in Methodology, and Pay It Forward help to retain women in the profession by providing concrete strategies for survival and success. New scholarship on gender and citations in the American Political Science Review—and a new all-female editorial board—offers encouragement (Breuning et al. Reference Breuning, Gross, Feinberg, Martinez, Sharma and Ishiyama2018). Building on the survey, our larger book project underscores that the call for more equitable norms and practices does not come from one lonely voice or even a small group of voices but rather from a persistent chorus of scholar–parents working in all stages and settings within the profession.