For much of U.S. history, constitutional conventions were called regularly to frame, revise, and amend state constitutions. From the 1770s through the 1970s, the 50 states held nearly 250 constitutional conventions, many of which brought about important changes in governance. These conventions were responsible for expanding and occasionally contracting voting rights as well as recognizing and adjusting other rights. Conventions also reshaped governing institutions, expanded opportunities for direct popular participation in lawmaking, constrained governing authority in notable ways, and authorized and enacted various public policies. 1

After many years when conventions were called regularly, recent decades have seen little convention activity. Aside from a short-lived 1992 Louisiana convention composed entirely of legislators, 2 the last full-scale convention took place in 1986 in Rhode Island after voters approved an automatically generated convention referendum placed on the ballot independent of legislative action. 3 The recent lack of conventions is partly a result of voters rejecting convention referenda that occasionally appear on state ballots, but it is also a product of state legislatures’ unwillingness to submit convention referenda for voter consideration. It has been over forty years (when an Arkansas convention was held in 1979–80) since a convention was convened after voter approval of a legislature-referred referendum. 4

The recent absence of conventions, in contrast with their earlier regularity, has prompted scholars to focus on the contemporary era and explain the declining support during the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. 5 As has been shown, legislators are hesitant to call conventions due to fears that they will adopt reforms that weaken the legislature as an institution, as well as gain control of the policy agenda and advance measures disfavored by legislators, and also elevate the profile of convention delegates and position them as electoral rivals to legislators. 6 When voters encounter convention referendums, they express various worries about conventions, including concerns that they will open a “Pandora’s box” by addressing unanticipated topics and adopting controversial changes. 7 Opposition is also prevalent among groups and organizations that are afraid that conventions will overturn these groups’ favored constitutional commitments and provisions. 8

My purpose in this article is to examine the contrast between the prior regularity of conventions and their recent absence, but to adopt a different perspective than is usually taken—not by explaining the recent absence of conventions and identifying obstacles to calling them but rather explaining the frequency in earlier eras and accounting for why various obstacles were overcome regularly from the 1770s through the 1970s. I am particularly interested in explaining why legislatures in prior eras agreed to submit convention referendums for popular approval or take other steps to call conventions. Other scholars have analyzed voter decision making on convention referendums. 9 I leave aside for present purposes questions about voter behavior so as to focus on legislators and their willingness to call conventions.

To investigate this question, I first identify the state constitutional conventions held in the United States, drawing on previously compiled lists and making various adjustments and arriving at a count of 250 conventions. Working from this list, I identify 77 of these conventions that were called to create inaugural state constitutions. Another 50 conventions were called for reasons stemming from the Civil War, including conventions called to secede from the Union and make necessary changes in state constitutions, then rejoin the Union and make state constitutional changes required as part of Reconstruction, and then later reverse changes adopted during Reconstruction. Another 41 conventions were called not at the instigation of legislatures but rather through automatically generated conventions or referendums or councils of censors or federal courts. Putting aside these conventions leaves 82 conventions called at the discretion of legislators and for reasons unrelated to joining, leaving, or rejoining the Union.

My focus is on explaining legislators’ willingness to call these 82 discretionary conventions by first identifying the issues that can be credited with overcoming legislators’ traditional opposition to holding conventions. As I show, three issues have outpaced all others in generating these conventions: (1) legislative apportionment, (2) fiscal issues, especially taxation and debt, and (3) the judiciary, especially the selection of judges and structure of the court system.

It is also possible to identify circumstances that contributed on a regular basis to legislators’ willingness to call conventions and overcome their traditional opposition. Four factors are particularly important: (1) Conventions were in some cases the only means of making changes to state constitutions, when other amendment mechanisms were not yet available, or they were viewed as facilitating a quicker response to pressing concerns than was possible through alternative mechanisms. (2) Legislators have been willing in some cases to call conventions when they can maintain control over the convention’s agenda or membership. (3) Governors have often played a critical role in mobilizing public support for conventions and pressuring legislators to overcome their usual reluctance to support them. (4) Conventions have sometimes been called in response to changes in the strength of political parties in state legislatures, especially when a newly dominant party is intent on reversing constitutional changes made by a displaced party.

The main benefit of this study is to contribute to an understanding of the conditions when constitutional conventions can be called, by showing that legislators’ opposition to calling conventions is a constant feature of politics that can only be overcome under certain conditions and was overcome on a number of occasions in the nineteenth century and during much of the twentieth century.

STATE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS IN THE UNITED STATES

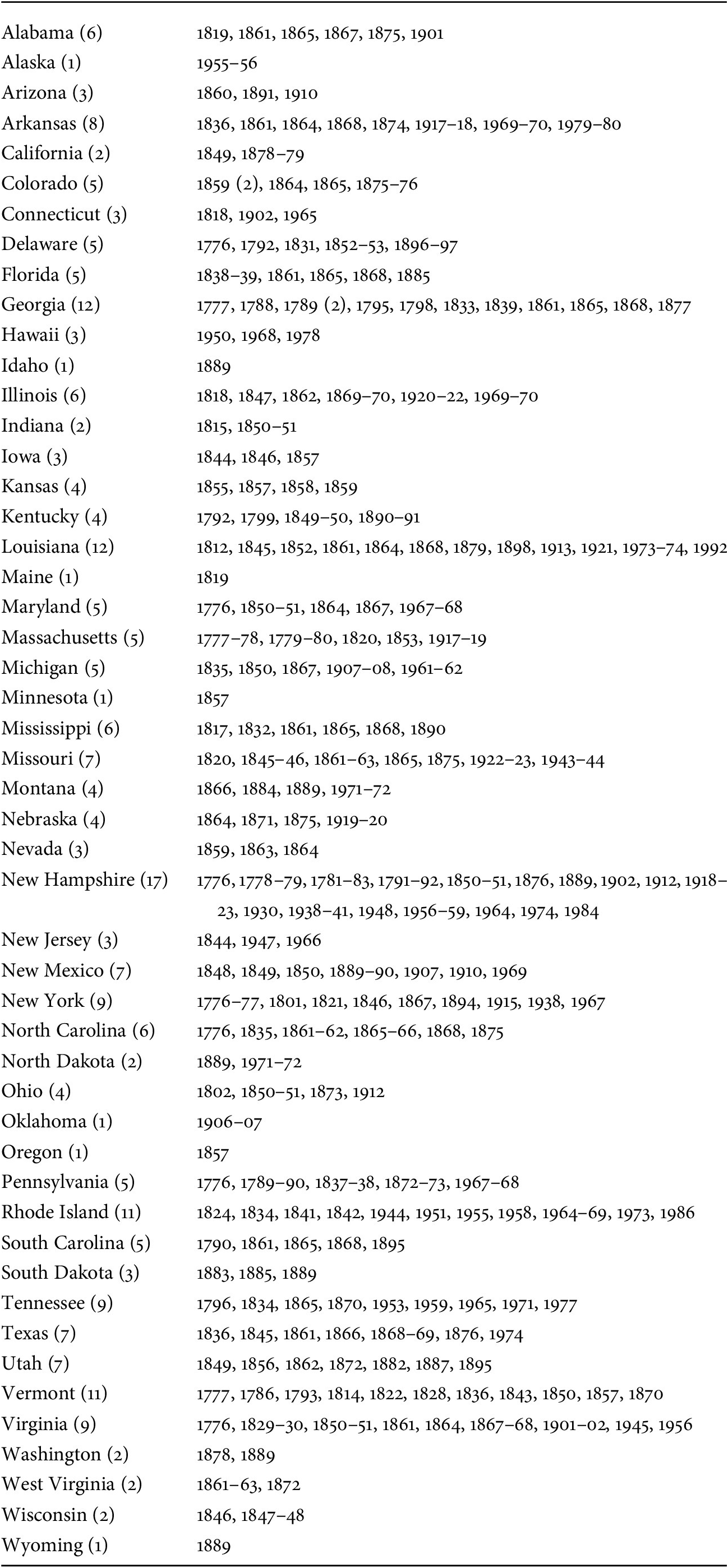

It is helpful to begin by identifying the state constitutional conventions held in the US and highlighting several issues that have to be confronted in undertaking such a count. 10 Various scholarly efforts have been undertaken in this respect, including a list initially compiled by Albert Sturm and updated through the years, 11 a list constructed and maintained by J. H. Snider, 12 and a list compiled by Robinson Woodward-Burns in a just-published book. 13 Working from these lists and making adjustments, I generated a list of 250 conventions, as shown in Table 1.14

Table 1. State Constitutional Conventions

Several decisions have to be made about what qualifies as a state constitutional convention, and in a way that could result in a slightly higher or lower count, depending on how these challenges are resolved. In fact, it is less important to settle on a precise number of conventions than to identify the definitional issues to be confronted and decisions to be made when counting conventions.

One key decision is determining what counts as a convention. In a few instances in the 1770s and then again in the 1860s and 1870s, state constitutions were drafted by provincial congresses and sometimes by legislatures. The distinction between conventions and provincial congresses is not always clear, especially during the 1770s when states experimented with a wide range of procedures during an initial wave of constitution-making. 15 Determining what qualifies as a convention is particularly difficult in the case of four constitutions adopted in the months prior to the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. New Hampshire on January 5 and South Carolina on March 26 adopted the first state constitutions through the work of provincial congresses. These two constitutions were intended to be temporary, until more enduring constitutions could be drafted, as was done in New Hampshire through conventions in 1778–79 and 1781–83 and in South Carolina through a legislature-drafted constitution in 1778 and then through a convention-drafted constitution in 1790. 16 Also in the month before the Declaration of Independence, a revolutionary convention in Virginia promulgated a declaration of rights on June 12 and a frame of government on June 29, 17 and a provincial congress in New Jersey enacted a constitution on July 2. 18

Scholars have reached varying conclusions about how to characterize these initial assemblies. The standard approach has been to consider New Hampshire and Virginia to have held conventions in 1776, in part because the gatherings were labeled conventions at the time, 19 but to consider conventions not to have been held in South Carolina in 1776 or in 1778 or in New Jersey in 1776. In each of the other cases where states framed constitutions after the Declaration of Independence—in Delaware (1776), Pennsylvania (1776), Maryland (1776), North Carolina (1776), Georgia (1777), New York (1777), Vermont (1777), and Massachusetts (1777–78 and 1779–80)—the proceedings clearly merit designation as conventions. 20 Notably, two of the original thirteen states—Connecticut and Rhode Island—retained their colonial charters until 1818 and 1843, respectively, and did not draft constitutions during the founding era.

Then, in two instances in the 1860s and 1870s state legislatures tried to frame constitutions, in one case successfully, in ways that yield a more easily resolved set of decisions about whether to designate these gatherings as conventions. In Nebraska, the state’s inaugural 1866 constitution was drafted not by a convention but by a territorial legislature, which submitted the document to voters for ratification, in a move that led to the state joining the Union the following year. 21 New Mexico’s bid for statehood took much longer. On a half-dozen occasions, in 1848, 1849, 1850, 1889, 1907, and 1910, conventions were held in New Mexico to draft constitutions with an eye toward joining the Union, until success was finally achieved after the 1910 convention. However, one effort to draft a New Mexico constitution during this period, in 1872, has been labeled a convention in some prior accounts 22 but appears on closer inspection to be the work of a territorial legislature and in a way that does not merit designation as a convention. 23

Still another decision to be made, as illustrated by New Mexico holding six conventions prior to statehood, is determining how to treat various prestatehood conventions that were held in some states. Several states held multiple conventions as part of a long process of forming territorial governments and transitioning from territorial status to statehood. Previous lists have included some of these prestatehood conventions. However, Robinson Woodward-Burns has recently taken note of additional prestatehood conventions that merit inclusion, resulting in a higher count than in some prior lists. 24

Another key decision is determining what counts as a state constitutional convention. In the early 1850s, several state legislatures called conventions to reconsider the relationship between the state and federal government, but without considering or making any changes to the state constitution. Although some prior accounts have included one of these gatherings, an 1851 Mississippi convention, in lists of state constitutional conventions, 25 this Mississippi gathering is more properly viewed as something other than a state constitutional convention. 26 On the other hand, conventions held to secede from the Union in 1860 and 1861 in twelve of the thirteen southern states (all but Tennessee) as well as in Missouri, where convention delegates ultimately rejected secession, are properly understood as state constitutional conventions because secession was accompanied by changes to state constitutions.

DISCRETIONARY CONVENTIONS INSTIGATED BY LEGISLATURES FOR REASONS NOT CONNECTED WITH JOINING, LEAVING, OR REJOINING THE UNION

My focus in this study is explaining why legislatures agreed to call conventions. Therefore, I set aside for present purposes conventions instigated by entities or devices other than legislatures. I also set aside, due to their exceptional nature, conventions that were called for reasons associated with the Civil War. My purpose in separating these other conventions is to make clear that only a portion of the convened conventions in the US have been discretionary conventions instigated by legislatures and to focus on explaining why these conventions were called. Identifying the precise number of legislature-instigated discretionary conventions—I count 82 such conventions—is less important than making clear that they are unusual occurrences that call out for explanation when they take place.

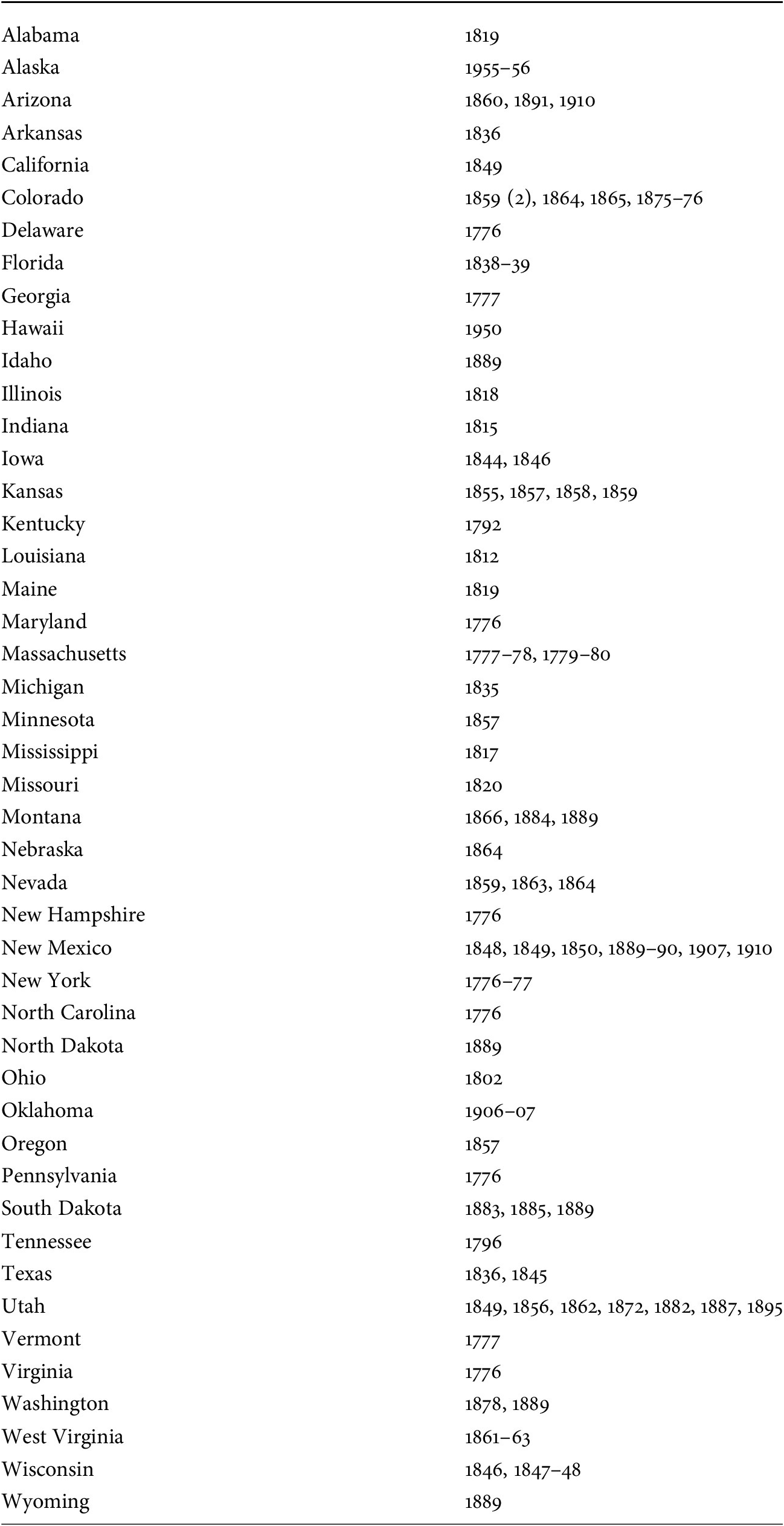

Founding Conventions

Seventy-seven state constitutional conventions, listed in Table 2, were called for the purpose of drafting inaugural constitutions and preparing for joining the Union. Most states held a single founding convention that approved a constitution and led to the state’s admission to the Union. However, some states held multiple conventions before success was achieved in framing a constitution and securing admission to the Union, whether because initial conventions were unable to agree on framing a constitution, or voters rejected the work of early conventions, or Congress was not yet prepared to grant statehood even when a convention produced a constitution that was approved by voters. Utah held seven conventions before statehood was achieved, whereas New Mexico held six such conventions; Colorado held five of these conventions; Kansas held four conventions of this kind; and Arizona, Montana, Nevada, and South Dakota each held three founding conventions.27

Table 2. Conventions Convened to Frame Inaugural Constitutions

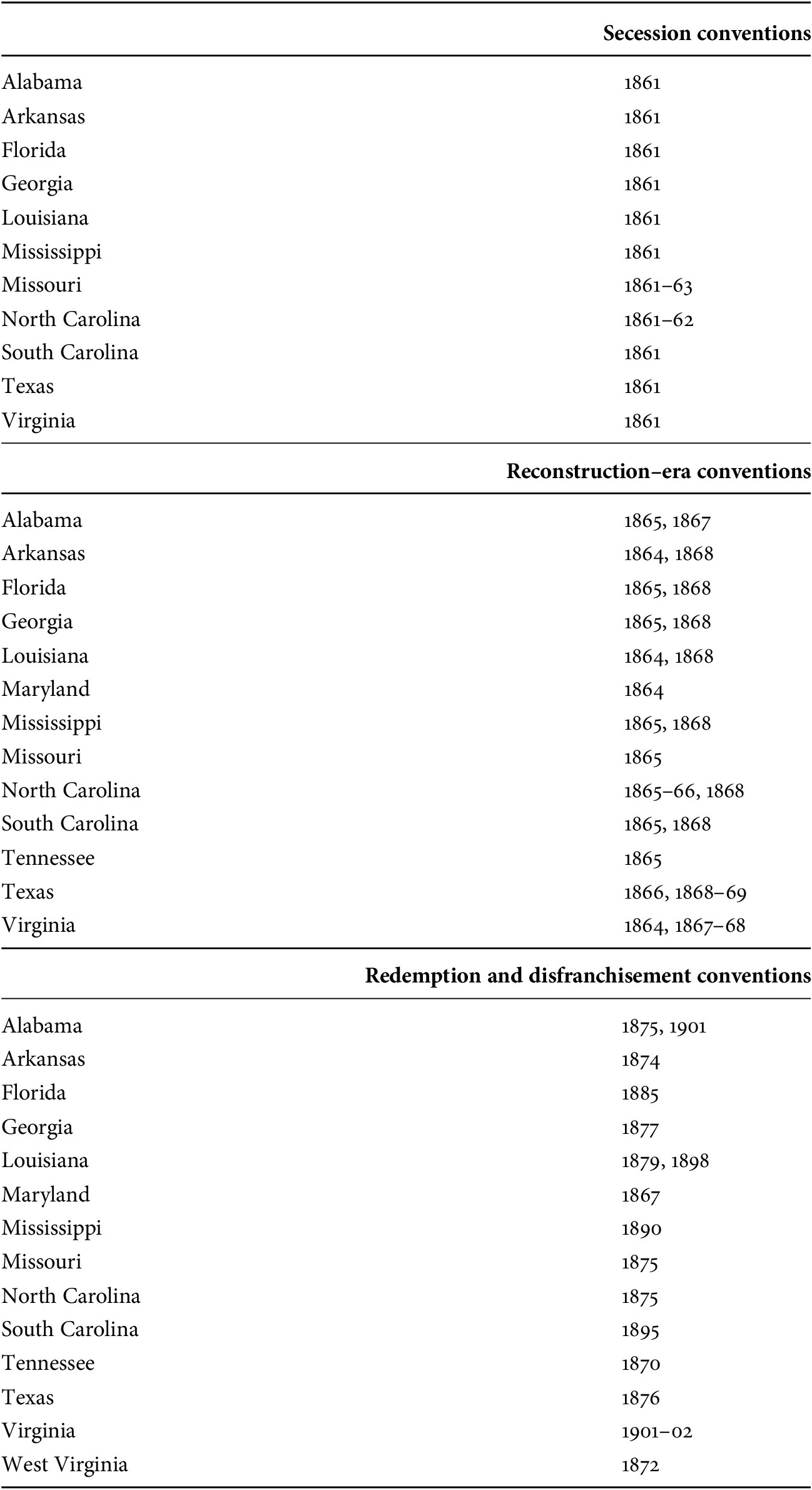

Conventions Called during, after, and as a Consequence of the Civil War

Fifty conventions were called for reasons directly or closely related to the Civil War—whether in the 1860s to leave or rejoin the Union or in subsequent decades to reverse provisions that had been adopted in the process of and as a condition for rejoining the Union. In some of these cases, especially during Secession and then later during Redemption and Disfranchisement, conventions were called at the discretion of legislatures. In most other cases, especially during Presidential Reconstruction and Congressional Reconstruction, conventions were called at the direction of federal officials and as a condition for rejoining the Union. However, the common theme running throughout these eras is that none of these conventions would have been called if southern states had not left the Union and the Civil War not taken place, as Paul Herron has shown in a comprehensive analysis of conventions held in southern states in a series of waves from the early 1860s through the early 1900s. 28 Table 3 lists the conventions held for these various purposes, taking note of conventions held in southern states and several Border States for reasons related to the Civil War.29

Table 3. Conventions Convened for Reasons Related to the Civil War

An initial wave of 11 conventions in southern and Border States was called to consider seceding from the Union and then to make various changes in state constitutional provisions. 30 At a minimum, once the decision was made to secede from the Union, state constitutions had to be changed to provide for selection of representatives to the Confederate Congress rather than the U.S. Congress. 31 Some conventions also changed other state constitutional provisions and in ways not connected with separating from the Union, whether by changing the means of selecting judges or altering the structure, powers, or means of apportioning the legislature, or changing tax provisions or voting rights, among other changes. 32 These conventions were called during 1860 and 1861 in ten of the eleven states that seceded from the Union as well as in Missouri, which eventually decided against secession. Tennessee was the only state that joined the Confederacy and did not hold a convention. Voters in Tennessee rejected a referendum on holding a convention; eventually, the legislature submitted to voters a secession referendum that was approved. 33 Missouri is the one state where a convention was called to consider secession but convention delegates decided against leaving the Union. However, Missouri’s convention continued to meet in a series of sessions between 1861 and 1863, approving a number of changes in the state constitution and taking other actions. 34

The mid and late 1860s brought two more waves of conventions related to the Civil War, first to take steps to satisfy federal directives as part of Presidential Reconstruction and then in response to federal requirements for rejoining the Union as part of Congressional Reconstruction. During these two waves of conventions in the mid to late 1860s, 23 conventions were held, mostly to change southern state constitutions to conform to federal requirements for rejoining the Union and also, in the case of two Border States, to abolish slavery. Eleven of these conventions were called in southern states pursuant to Presidential Reconstruction, either in the final years of the Civil War as federal troops gained control of some or all of the territory in these states or in the immediate aftermath of the War. During this period, from 1864 to 1866, all of the former member states of the Confederacy held conventions to abolish slavery and rescind secession ordinances and recognize the supremacy of the federal government. 35 Meanwhile, two Border States, Maryland (1864) and Missouri (1865), called conventions to frame constitutions to abolish slavery and in the process disfranchise and impose other restrictions on Confederate sympathizers. 36 Ten of the member states of the Confederacy (all but Tennessee) were then required to hold another round of conventions in 1867–1868 as part of Congressional Reconstruction. Pursuant to congressional Reconstruction Acts, these conventions were required to frame new state constitutions that enfranchised African Americans and also take other steps such as ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment before states could be readmitted to the Union with full representation in Congress. 37 Among other changes made to state constitutions during Congressional Reconstruction, conventions established state systems of free public education and also strengthened the office and power of the governor in various ways. 38

A final wave of Civil War-related convention activity in southern and border states lasted from the late 1860s to the early 1900s and produced 16 conventions that focused on reversing changes made by Reconstruction-era conventions, first as part of Redemption conventions and then as part of Disfranchisement conventions. Eleven of these conventions took place during the Redemption era and were generally held in the 1870s and 1880s. As Republicans and Unionists lost control of southern state governments and as conservative Democrats regained control in southern states and several Border States, legislatures sought to reverse state constitutional changes adopted by Reconstruction-era conventions. 39 Conventions were held during this era in eight of the former Confederate states (in all but Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia) and also in the border states of Maryland, West, Virginia, and Missouri. 40 These conventions removed restrictions on voting and office-holding by Confederate sympathizers and occasionally revisited earlier constitutional arrangements regarding public support for education and other programs. Then, in the 1890s and early 1910s, five southern states held conventions as part of a Disfranchisement Era: in Mississippi (1890), South Carolina (1895), Louisiana (1898), Alabama (1901), and Virginia (1901–02). These conventions went even further than Redemption conventions in reversing reforms adopted during Reconstruction, generally by limiting the ability of African Americans to vote. 41

Conventions held in these later waves, during the Redemption and Disfranchisement eras, were, admittedly, not tied to the Civil War in quite the same way as earlier waves of Secession and Reconstruction conventions. During this later period, conventions were called for a variety of reasons—not only to reverse Reconstruction-era changes in state constitutions but also to make other changes, such as establishing commissions to regulating railroads and other corporations. Nevertheless, the desire to overturn changes adopted during the Reconstruction Era was the dominant reason why these conventions were called.

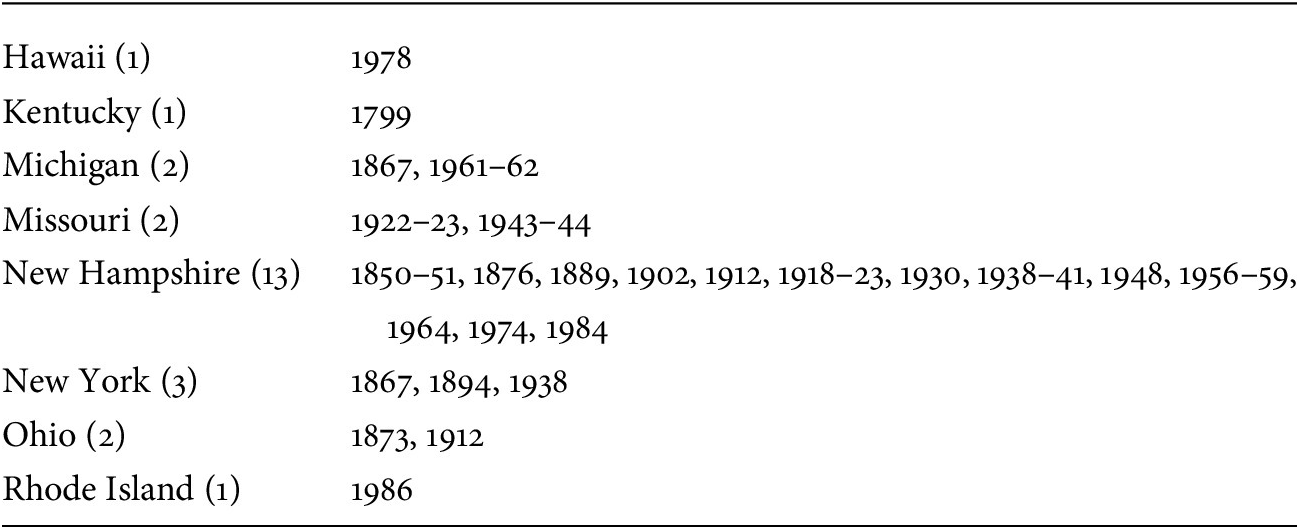

Conventions Called at the Instigation of Officials or Devices Other Than Legislatures

Another 41 conventions were not instigated by legislatures. This includes three conventions—in New Hampshire (1791–92) and Georgia (1795 and 1798)—that were the product of state constitutional provisions mandating that a convention be held after a certain interval of time. New Hampshire’s 1784 Constitution required a convention to be called after a seven-year interval, thereby leading to a 1791–92 convention. 42 Georgia’s 1789 Constitution required a convention to be held in 1795. 43 Delegates to Georgia’s 1795 convention that was held pursuant to this provision then approved a constitutional provision requiring another convention to be held in 1798. 44

Twenty-five conventions, listed in Table 4, were called as a result of constitutional provisions mandating that convention referenda be submitted to voters at periodic intervals.45 In one case, Kentucky’s 1792 Constitution established a one-time procedure for gauging public support for a convention. After Kentucky voters expressed support for a convention in referenda held in 1797 and 1798, thereby satisfying a constitutional requirement that a convention would be called if majority support was recorded in both years, this resulted in a 1799 convention.46 Other conventions were held as a result of state constitutional provisions requiring a convention referendum to be placed on the ballot at regular intervals on an enduring basis. Most of these conventions were called in New Hampshire. In 1792, New Hampshire’s constitutional provision mandating that a convention be held after a seven-year interval was changed to require that a referendum on holding a convention be submitted to voters at seven-year intervals.47 Then, in 1964 the interval between submission of a convention referendum in New Hampshire was lengthened to ten years where it currently stands. Four other state constitutions require submission of a convention referendum at similar ten-year intervals: Alaska, Hawaii, Iowa, and Rhode Island. Michigan provides for a convention referendum every 16 years. Eight states currently require submission of a convention referendum at 20-year intervals: Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, New York, Ohio, and Oklahoma.48

Table 4. Conventions Convened via Mandatory Convention Referenda

Ten conventions, all in Vermont, were called at the direction of a council of censors. Vermont is one of two states, along with Pennsylvania, whose original constitution provided that every seven years a council of censors should convene and would have the authority to call a convention to propose constitutional reforms. 49 Although the council of censors was soon eliminated in Pennsylvania, it was maintained in Vermont for nearly a century before it was eliminated. Councils of censors were responsible for calling conventions in Vermont in 1786, 1793, 1814, 1822, 1828, 1836, 1843, 1850, 1857, and 1870. 50

Three other conventions were called because courts issued rulings in the 1960s ordering conventions to be held to reapportion the state legislature. To be sure, as discussed in more detail below, several other conventions were called in the 1960s in response to U.S. Supreme Court rulings in the early part of the decade mandating that legislative districts be apportioned according to a one-person/one-vote principle. In states whose constitutions explicitly deviated from population equality in drawing districts, often by requiring legislative seats to be apportioned equally by county or setting a minimum number of seats per county, it was necessary to change these state constitutional provisions, whether by calling conventions or by adopting amendments. In many states, legislators faced a choice about whether to call a convention to make the necessary changes or to simply draft amendments for submission to and ratification by voters, with many states deciding to follow the piecemeal amendment route and some other states deciding to call conventions. However, in three clear cases, in Connecticut (1965), 51 New Jersey (1966), 52 and Hawaii (1968), 53 state officials did not have any choice because courts issued rulings directly ordering or coming very close to ordering states to call conventions to remedy constitutional provisions responsible for malapportionment. 54 In each of these cases, judges viewed conventions as capable of adopting remedies more quickly than would be possible through legislature-referred amendments or they did not trust malapportioned legislatures to create an effective solution via the amendment process.

EXPLAINING LEGISLATURES’ SUPPORT FOR CALLING CONVENTIONS

Once the focus is placed on 82 conventions called by and at the discretion of legislatures for purposes other than joining, leaving, or rejoining the Union (see Table 5), it becomes possible to identify explanations for why legislatures were willing to call them, either by submitting a convention referendum for voter approval or, in some cases, calling a convention without putting the question to a public vote.55 In seeking explanations for why these conventions were called, I consulted materials tracing the history and development of the 50 state constitutions. The most valuable sources are the volumes in the Commentaries on the State Constitutions of the U.S. series edited by G. Alan Tarr. I supplemented these accounts with books, articles, and official records regarding particular state constitutions and conventions. In drawing on these sources to account for how legislators overcame their usual opposition to conventions, I focus on two complementary explanations—first, identifying the main issues capable of generating sufficient pressure for calling conventions and, second, identifying the leading circumstances associated with legislators’ willingness to support conventions.

Table 5. Conventions Convened at the Discretion of Legislatures for Purposes Other Than Joining, Leaving, or Rejoining the Union

It will be helpful to offer some remarks about the method and approach I have taken in investigating these questions, starting with the approach taken to identifying the main issues that spurred the calling of these conventions. With some conventions, all evidence points in favor of a single dominant issue or several key issues that were prominent in the minds of legislators and voters when calling them. In cases of this sort, when scholarly accounts of convention origins are all aligned, it is not difficult to pinpoint the issues that prompted conventions to be called and the specific reasons legislators were led to support them. In other cases, judgment calls have to be made for various reasons. Occasionally, scholarly accounts diverge in their assessments of which issues were most prominent in the lead-up to the convention. Additionally, some conventions were called for a wide range of reasons and without one or two issues taking precedence. Moreover, the issues prominent in the lead-up to the convention occasionally diverge from the issues that surfaced after the delegates convened, and I am most concerned with the former issues.

The scholarly challenges are even more significant when determining which circumstances played a role in leading legislators to overcome their traditional concerns about calling conventions and ceding authority to convention delegates. Scholarly accounts of conventions’ origins occasionally discuss the role of public opinion, political party dynamics, interest-group activity, and the influence of governors and judges on legislators’ willingness to approve convention calls. In some cases, it becomes possible to rely on these accounts to isolate the importance of certain factors in pressuring or enabling legislators to agree to call conventions. In other cases where the record is less clear about the effect of these various factors and the reasons why legislators overcame their traditional opposition to conventions, judgment calls have to be made in identifying the circumstances responsible for conventions being called.

ISSUES RESPONSIBLE FOR CALLING CONVENTIONS

Three sets of issues proved important in generating support for conventions on an enduring basis: legislative reapportionment, taxation and debt, and judicial selection and structure. To be sure, several other issues were occasionally important in generating conventions, including expanding the suffrage and adjusting the relationships between state and local governments and between the legislative and executive branches. Nevertheless, reapportionment, finances, and the judiciary were the main recurring issues.

Reapportionment

No issue has been more important in generating conventions on a regular basis than legislative reapportionment. In the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, reapportionment was the leading issue or among the two or three leading issues prompting conventions to be called in New Hampshire (1778), South Carolina (1790), New York (1801 and 1820), Rhode Island (1824, 1834, 1841, and 1842), Virginia (1829–30 and 1850–51), Georgia (1833 and 1839), North Carolina (1835), Louisiana (1845), Missouri (1845), Maryland (1850–51), Delaware (1852–53), and Massachusetts (1853). 56 In several of these states, residents of piedmont or transmontane areas sought to rebalance existing apportionment plans to take account of population movement from the east toward the west. In other cases, urban residents sought to alter apportionment plans that favored rural areas and had not been updated to take account of migration to cities. Admittedly, groups pressing for conventions in these situations often sought to place other issues on the agenda aside from securing more equitable apportionment. However, each these conventions, along with additional conventions held around the turn of the twentieth century in Delaware (1896–97) and Connecticut (1902),57 were prompted in large part by concerns about reapportionment.

It is easy to understand why residents of underrepresented regions pushed to hold conventions with an eye toward securing more equitable apportionment plans. It is less clear why legislators acquiesced to calling conventions in response to these concerns. After all, many legislators who benefited from existing malapportionment plans had little incentive to support conventions with the power to redraw district lines and the potential to reduce their own political influence and risk losing their offices. Yet residents of underrepresented areas were in some cases able to overcome legislators’ resistance by pressuring or persuading them to call conventions. Success in calling these conventions was in many cases achieved through the work of broad-based movements that sought, sometimes working for several decades, to elevate the prominence of their concerns in the public mind and put pressure on legislators to call a convention. These groups and movements were at times willing to engage in extralegal and extraconstitutional activity, which in a few cases led to mob violence and even threats of revolution and secession, all of which contributed to legislatures’ willingness to accede to public pressure to call conventions. 58

Calling a convention was no guarantee that convention delegates, once assembled, would actually approve a more equitable apportionment plan, especially if delegates were selected from the same malapportioned districts as current legislators. 59 In some cases, convention delegates were unable to agree on a revised apportionment plan, as in Rhode Island in 1834, 60 or made only minimal changes to existing district maps and fell well short of achieving significant reform, as in Virginia in 1829–30. 61 Nevertheless, the public pressure applied to convention delegates was often so strong that conventions often produced more equitable apportionment plans, even if they did not resolve the issue to the full satisfaction of aggrieved regions.

In the 1960s, U.S. Supreme Court reapportionment rulings imposing a one-person/one-vote standard were responsible for another wave of conventions. As Albert Sturm has argued, these court rulings requiring a more equitable apportionment enabled the calling of conventions by removing a leading reason why legislators had been reluctant to allow conventions to be called. As Sturm wrote, in so far as these rulings “made state legislative reapportionment inevitable, a principal stumbling block to calling constitutional conventions was removed… For many decades legislatures had frustrated efforts to call conventions because they feared that these bodies would include reapportionment in their proposals for change, thereby jeopardizing the existing advantage of rural interested in the legislative power structure.” 62

Judicial rulings in the 1960s regarding reapportionment occasionally had an even more direct effect on calling conventions. In some states, complying with the Court’s new one-person/one-vote standard required not only that legislative district lines be redrawn but also that the state constitution be changed to eliminate rules that required equal representation of counties or provided in some other fashion for representation of territory rather than population. Changes to these state constitutional provisions could have been achieved by passing legislature-drafted constitutional amendments. But in a few cases, in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Hawaii, as discussed earlier, federal courts issued rulings essentially requiring that these constitutional changes be undertaken by constitutional conventions. In still other states, courts issued rulings requiring changes in state constitutional provisions but did not directly order that these changes be made via conventions. In some of these latter cases, legislatures exercised their discretion and called conventions that were intended in large part to remedy malapportionment. This includes conventions in Rhode Island (1964–69), Tennessee (1965), New York (1967), and Maryland (1967–68). 63

Finances

Conventions have often been called to consider fiscal issues, especially borrowing and taxing. In the 1840s and 1850s, a number of conventions were called primarily in response to extensive state involvement in building roads, canals, and railroads. After states invested heavily in these projects in the 1820s and 1830s, an economic downturn in the late 1830s led to the failure of many of these ventures, prompting some states to default on their debt payments and forcing a number of states to generate more revenue to pay off debt incurred as a result of public entanglement in these projects. All of these developments generated calls to limit state legislatures’ involvement in internal improvements and make it more difficult to undertake future borrowing. 64 Conventions called in New York (1846), Illinois (1847), Michigan (1850), Maryland (1850–51), Ohio (1850–51), and Indiana (1850–51) all had as one of their main purposes the task of constraining legislatures’ ability to invest in internal improvements and incur future debt. 65

In contrast with conventions that were called to remedy malapportionment and that generated opposition from many legislators who feared a loss of power for themselves and their regions, conventions called in response to internal improvement projects and burgeoning debt did not encounter strong legislative resistance. To be sure, some legislators who had voted in earlier years to support legislation investing in canals and railroads had an interest in defending these votes and were not eager to support calls for conventions where their votes would be condemned. For the most part, though, by the 1840s and 1850s legislators were aligned with the public in concluding that legislatures had been imprudent in borrowing heavily and agreed that there was a need to impose constitutional constraints on borrowing to prevent future occurrences of legislative exuberance in support of these projects. 66

Tax-related concerns have also played a part in prompting successful calls for conventions. In several cases in the nineteenth century, conventions were called to adjust tax burdens seen as falling disproportionately on certain groups or regions. To this end, Tennessee’s 1834 convention was called to bring about more uniformity in taxation in rural and urban areas and eastern and western regions. 67 Meanwhile, California’s 1878–79 convention was called with the intent of shifting the tax burden from lower-income persons and farmers to higher-income earners and corporations. 68

In other cases, especially in the twentieth century, taxation concerns prompted conventions to be called to reconsider constitutional provisions seen as unduly limiting the ability to levy taxes. Some conventions have been called to grant legislators more discretion in levying taxes, as in Arkansas (1969–70 and 1979–80), 69 where taxation was one of several reasons for calling these conventions, or to allow for classifying property and taxing different classes of property at different rates, as in Tennessee (1971), where a convention was called solely to deal with property-tax classification and limited to addressing that issue alone. 70 A 1992 Louisiana convention was also called entirely to deal with taxation and related fiscal issues, in this case with an eye toward reconsidering the balance of sales, property, and income taxes. 71

Judicial Structure and Selection

Concerns about judicial selection and structure have played a surprisingly prominent role in generating conventions. Although issues surrounding the organization of state courts and selection of judges have only occasionally been the sole cause of conventions, they have been among two or three main reasons for calling conventions when recent judicial decisions proved controversial or when court systems were seen as in need of updating and in a comprehensive fashion. At times, conventions have been called for the purpose of changing the structure of the court system, whether by adding or eliminating courts or altering their jurisdiction or creating unified court systems. Issues of this sort proved important for calling conventions in Delaware (1792 and 1831), Tennessee (1834), Ohio (1850–51), Delaware (1896–97), New York (1967), Pennsylvania (1967–68), and New Mexico (1969). 72 At other times, the main concern has been changing the way judges are selected. A convention in Mississippi (1832) was called primarily to provide for elected judges, at a time when state courts were viewed as insufficiently responsive to public opinion. 73 Similar concerns played a role in calling conventions in Pennsylvania (1837–38), where eliminating life tenure for judges was one of a handful of goals sought by convention supporters, 74 and in Missouri (1845), Kentucky (1849–50) and Maryland (1850–51), where calls to move from appointed to elected judges played a role, alongside other issues, in prompting conventions to be called. 75

Other Recurring Issues

Several issues aside from reapportionment, debt and taxation, and judicial structure and selection have also been responsible for generating conventions on a regular basis and are worthy of mention. Several conventions were called to address voting rights. At times, the main concern was expanding the suffrage, as in Virginia (1829–30 and 1850–51), Pennsylvania (1837–38), Rhode Island (1841 and 1842), Louisiana (1845), and Delaware (1852–53). 76 At other times, conventions were called to adjust the processes of registration and voting, as in Rhode Island (1944), Virginia (1945), and Rhode Island (1958). 77

Separation of powers issues also generated several conventions. Disputes between the legislature and executive branch regarding the appointment power were among the leading reasons for calling conventions in Delaware (1792), New York (1801 and 1820), and Pennsylvania (1837–38). 78

In other cases, conventions were called less in response to specific issues and concerns and more in response to broad movements not easily reduced to a single issue or cause. During the Progressive Era in the early 1900s, conventions were called to make governing institutions more responsive to public opinion in wide range of ways, as in Michigan (1907–08), Massachusetts (1917–19), Arkansas (1917–18), Nebraska (1919–20), and Illinois (1920–22). 79 Then, in the early 1970s, conventions were called in several states with an eye toward undertaking a general modernization and updating of state constitutional provisions, as in Illinois (1969–70), North Dakota (1971–72), Montana (1971–72), Louisiana (1973–74), and Texas (1974). 80

CIRCUMSTANCES ASSOCIATED WITH CALLING CONVENTIONS

In considering why legislators were at times willing to overcome their general opposition to calling conventions, it is important to consider not only the issues responsible for generating support for conventions but also the circumstances associated with conventions being called. Four contextual factors have proved particularly important: first, the difficulty of accessing constitutional change mechanisms other than conventions, second, legislators’ ability to control conventions’ agendas, third, the effectiveness of governors in making a public case for conventions and overcoming legislative opposition, and fourth, shifts in legislative party control that led a newly installed party to reverse constitutional changes initiated by a displaced party.

Amendment Rules

Conventions were called in a number of cases in earlier years because some state constitutions did not yet provide any other means of making constitutional changes. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, state constitution makers experimented with a range of mechanisms for changing state constitutions. Most state constitutions during this period established procedures for calling conventions, but there was less uniformity in the availability of other procedures for changing state constitutions. Several early state constitutions established procedures for legislatures to draft amendments. However, a number of states did not initially provide any means of adopting piecemeal amendments and only gradually allowed their constitutions to be changed via amendments. For instance, it took nearly a century for Virginia to adopt a procedure for legislature-generated amendments, until 1870, 81 and a similar length of time in Kentucky, until 1891, 82 and nearly two centuries before New Hampshire allowed legislature-generated amendments, in 1964. 83

Conventions were therefore called in situations when there was broad agreement on the need to change state constitutional provisions and no other vehicle for making these changes. On several occasions, conventions were called to address high-profile issues such as reapportionment when there was intense public pressure to deal with these issues and no other vehicles for changing the constitution to address these concerns, as in Virginia in 1829–30 and then in 1850–51. 84 In other cases, the issues in need of fixing were not high-profile issues such as reapportionment but nevertheless needed to be addressed and there was no other route for doing so other than via conventions. Such was the case in Georgia, when a trio of conventions were held in 1788 and 1789 (two in that year alone) for the purpose of changing the state’s 1777 constitution to take account of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and make changes in the state constitution accordingly. 85 Conventions were called for a similar purpose in Massachusetts in 1820, primarily in response to the separation of Maine (formerly a district of Massachusetts) and a need to make changes to the state’s 1780 constitution to take account of the split. 86 On still other occasions, the public and governing officials were in agreement on the need for a broad-based updating of state constitutional provisions, and the lack of amendment procedures required that this updating take place through a convention. This was the case in New Jersey in 1844, at a time when the state’s original 1776 constitution had gone unchanged for nearly seven decades, longer than any other initial state constitution. 87

Therefore, a significant number of conventions were called in the late 1700s and early 1800s, at a time when no other mechanisms were available for making constitutional changes. This includes conventions in Georgia (1788 and 1789), Massachusetts (1820), Virginia (1829–30 and 1850–51), Mississippi (1832), Tennessee (1834), North Carolina (1835), Pennsylvania (1837–38), New Jersey (1844), Louisiana (1845), Illinois (1847), Kentucky (1849 and 1890–91), Indiana (1850–51), Ohio (1850–51), and Iowa (1857). In most of these cases, as in Massachusetts, Mississippi, Tennessee, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Louisiana, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Iowa, the first convention called in such a situation opted to establish a legislature-generated amendment procedure going forward, 88 thereby reducing the need for calling future conventions in these particular states. 89

Even when states permitted changes to be made through either conventions or legislature-generated amendments, conventions were still seen as preferable to amendments on some occasions because constitutional changes could sometimes be made more quickly through conventions. States vary widely in their procedures for legislature-generated amendments. In the vast majority of states, legislators can propose amendments and voters can ratify them in much less time than it would take to call a convention and then for the convention to meet and submit its work for voter ratification. However, in a quarter of the states passing legislature-generated amendments is actually more time-consuming than calling a convention because amendments in these states have to be approved by legislators in two sessions separated by an intervening election before they can be submitted for voter ratification at still another election. 90

In this latter group of states, constitutional changes can be achieved more quickly through conventions than through legislature-generated amendments. This is why a number of conventions were called in the mid-twentieth century in Rhode Island, in 1944, 1951, 1955, and 1958: to make specific constitutional changes in an expeditious fashion, often for the purpose of updating voting processes. 91 In a similar situation, conventions were called in Virginia to allow specific constitutional changes to be adopted in a timely fashion in 1945 (allowing absentee voting by armed-service members during World War II) and also in 1956 (permitting public funds to support students attending private schools after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education rulings). 92

Limited Conventions

Legislators have been more comfortable calling conventions when they can control their work, generally by limiting their agenda. 93 By specifying a limited set of issues that convention delegates are permitted to address, whether one or two issues or a somewhat longer list, legislators can overcome a leading concern expressed by legislators and citizens alike about calling conventions: that they will open a Pandora’s box of issues. Focusing on discretionary conventions initiated by legislatures for reasons unrelated to joining, leaving, or rejoining the Union, legislatures provided for limited conventions of this kind in North Carolina (1835), Louisiana (1913 and 1992), Rhode Island (1944, 1951, 1955, 1958, and 1973), Virginia (1945 and 1956), Tennessee (1951, 1959, 1965, 1971, and 1977), and Pennsylvania (1967–68).

Occasionally, legislatures have proceeded in a slightly different fashion, not by specifying certain topics as permissible but rather designating certain topics off limits, in situations where legislators are particularly concerned with preventing action on these issues. For instance, legislators who are open to calling a convention but only if convention delegates do not disturb the existing apportionment plan may choose to foreclose consideration of that issue. In calling an 1850–51 convention in Maryland, for instance, the legislature stipulated that the convention could not reduce the clout that the city of Baltimore enjoyed in the current legislative apportionment plan (and further stipulated that the convention could not eliminate various constitutional protections for slavery). 94 Nearly a century later, the New Jersey legislature also took steps along these lines in framing a referendum that was approved by voters and led to a 1947 convention. In approving a convention call, New Jersey voters explicitly instructed delegates not to alter the plan of legislative apportionment. 95 At other times, legislators have been particularly concerned with preventing convention delegates from altering state bills of rights, which were designated off limits in Pennsylvania’s 1872–73 convention (which was also barred from creating separate courts of equity) 96 and Texas’s 1974 convention. 97 Meanwhile, in calling a convention in Pennsylvania in 1967–68, the main concern was to prevent delegates from authorizing a graduated income tax. 98

In a few recent cases, legislators have taken still another step toward exercising control over the work of conventions, by stipulating that legislators themselves will make up the entirety of the convention delegates. The Texas 1974 convention and Louisiana 1992 convention were composed solely of legislators and basically consisted of the legislature transforming into a convention for a designated time. 99 Other conventions have featured significant numbers of legislators serving as delegates, alongside a number of nonlegislator delegates. Therefore, the presence of legislators in convention delegations is by itself not unusual. What sets these recent conventions apart is that legislators devised an additional way of exercising control over their work, by limiting not only the convention agenda but also the composition of the convention delegates.

Gubernatorial Support

Governors have been uniquely situated to mobilize support for conventions and apply pressure on legislators to call conventions. Certainly, other groups and officials have played influential roles in campaigning for conventions. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries especially, convention supporters formed broad-based popular movements that elevated the salience of state constitutional concerns and made a case for addressing these concerns by calling conventions. 100 Public-interest groups such as the National Municipal League and League of Women Voters, among other organizations, were also active in the twentieth century in building support for state constitutional reform and occasionally through conventions. 101 However, governors have been more influential than any other persons or groups in building support for state constitutional reform and pressuring reluctant legislators to call conventions. 102

The critical role of governors in persuading and pressuring legislatures to call conventions was evident in many nineteenth-century conventions, including conventions in Connecticut (1818), called in response to Oliver Wolcott’s election and support; 103 Ohio (1850–51), called with the support of William Bebb; 104 Maryland (1850–51), called in response to the election and campaigning of Philip Francis Thomas; 105 Virginia (1850–51), called at the urging of John B. Floyd; 106 Delaware (1852–53), called in part at the request of William Ross; 107 and Pennsylvania (1872–73), called in response to John Geary’s efforts. 108

Governors also played primary roles in building support for conventions in the early twentieth century, especially during the Progressive Era. This includes conventions in Connecticut (1902), called to address legislative malapportionment at the urging of George McLean; 109 Michigan (1907–08), where Fred Warner was instrumental in campaigning for a convention; 110 Massachusetts (1917–19), after David Walsh made a case for a convention for several years and then Governor Samuel McCall continued the campaign; 111 Arkansas (1917–18), at the urging of Charles Hillman Brough; 112 Illinois (1920), in response to Frank Lowden’s efforts; 113 and Louisiana (1921), after John M. Parker highlighted the need for a convention in his successful bid for the governorship. 114

During the latter part of the twentieth century, as a different set of constitutional reform issues emerged, governors again took the lead in making the case for conventions and bringing them to fruition. This includes conventions called in New Jersey (1947), due to the efforts of several governors and capped off by a successful campaign led by Alfred Driscoll; 115 Pennsylvania (1967–68), a product of the work of several governors, including William Scranton and Raymond Shafer; 116 Maryland (1967–68), after Millard Tawes pressed the legislature to support a convention referendum; 117 Arkansas (1969–70 and 1979–80), due in the first instance to the efforts of Winthrop Rockefeller, the first Republican governor in the state since Reconstruction, and in the second instance to David Pryor; 118 and Louisiana (1973–74 and 1992), after Edwin Edwards rallied support for the former convention and then returned to the governor’s office two decades later and played a primary role in pressing the legislature to call the latter convention. 119

Shifts in Party Control

Occasionally, conventions have been called because shifts in party control of the state legislature led a newly empowered party to try to reverse constitutional provisions supported by the displaced party. 120 Pennsylvania’s 1790 convention is a classic case of a convention called after a shift in legislative party control. The Constitutionalists, so named because they supported Pennsylvania’s inaugural 1776 constitution, held the upper hand in state politics in the 1770s and for much of the 1780s. However, in the late 1780s, the Constitutionalists lost control to the Republicans, who had long opposed the 1776 constitution and were intent on reversing many of its provisions. Once Republicans gained control of the state government, they called a 1790 convention that promulgated a new constitution that discarded many of the features of the original constitution. 121

Other conventions were called in similar situations after one party displaced another in controlling state government. In Connecticut, the Federalist Party was in control in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and supported a religious establishment favoring the Congregational Church. Critics worked for some time to overturn this Congregational establishment, which was entrenched in the state’s colonial charter. Eventually, Democratic-Republicans joined forces with Episcopalians to accomplish this goal. In 1817, a Republican-Democratic alliance with Episcopalians succeeded in electing a Toleration Party candidate as governor. In the following year, the Toleration Party maintained control of the governorship and also gained control of the legislature and was at that point positioned to call a convention, which proceeded to frame Connecticut’s 1818 constitution and bring an end to the long-standing religious establishment. 122

Several decades later, in Iowa, as in a number of other states in the 1840s and 1850s, the chief competitors were the Democrats, who opposed banks and internal improvements, and Whigs, who supported these policies. Democrats controlled the convention that created Iowa’s inaugural 1846 constitution, which included a provision banning all banking operations. Whigs were highly critical of this antibanking provision and sought for the next decade to reverse it. In 1854, after Whigs won the governorship and the state house of representatives and came close to winning the state senate, they called a convention to write a new constitution and eliminate the antibank provision. 123

CONCLUSION

Identifying the state constitutional conventions held in the US and focusing on 82 conventions called at the discretion of legislatures for reasons unrelated to joining, leaving, or rejoining the Union is helpful in providing perspective on recent scholarship analyzing the absence of conventions since the 1980s. Contemporary inquiries have often focused on explaining the recent lack of conventions on the assumption that the frequent calling of conventions is the normal state of affairs and their absence is abnormal and in need of explanation. A benefit of shifting the scholarly focus to an earlier time, prior to the 1980s, is to show that state legislators’ opposition to calling conventions is a constant feature of state politics and capable of being overcome only under certain conditions. Therefore, what is in need of explanation is less legislators’ recent reluctance to call conventions than their earlier willingness to do so.

As I have shown in this article, certain issues have proved capable of generating sufficient pressure on legislators to call conventions or persuading them of the need to do so. Calls for conventions to remedy malapportionment have on one hand met significant opposition from legislators who risk losing their offices or influence, but these efforts have nevertheless been successful when residents of underrepresented regions have taken their case to the public for a sustained time and with great force and in a way that overcomes legislative resistance. Conventions have also been called on a regular basis to deal with financial challenges, at times because members of the public and legislators alike came to agree on the need to impose constitutional restrictions on legislators’ ability to borrow and tax and at other times, and for a very different purpose, in response to a consensus that restrictions adopted in prior eras were hamstringing the ability to raise funds for worthy projects. Conventions have also been called on a number of occasions to make changes in how state judges are selected, often by requiring judges to stand for election or changing the structure, organization, or jurisdiction of state courts.

Another lesson to be drawn from this study is that certain circumstances have contributed on a regular basis to overcoming legislators’ fears about calling conventions. In some states in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, conventions were the only option for adopting constitutional changes. Once states adopted legislature-generated amendment mechanisms, as nearly all states did by the mid-nineteenth century, there was much less pressure on legislatures to call conventions. This pressure was further reduced in states that began in the early twentieth century to provide as well for citizen-initiated amendments, a device eventually implemented in 18 states.

Legislators have occasionally been willing to call conventions when they have been able to retain significant control over them. A critical step that legislators have taken in this respect is limiting the subjects that conventions are permitted to address.

At times, legislatures have agreed to call conventions because they have been subject to tremendous pressure to do so, with this pressure applied most effectively by governors. Certainly, other groups play a role in publicizing the need for conventions and mobilizing public support, but no officials or entities are more effective than are governors in drawing public attention to the need for conventions and keeping the pressure on legislators to call them. In many cases where conventions have been held, legislators were not initially inclined to call them but were pressured to do so by governors who made calling a convention a central concern of their governorship.

Occasionally, conventions have been called after shifts in party control of the state legislature led a newly empowered party to reverse constitutional provisions adopted by a displaced party. On a number of occasions, state constitutional issues have become connected with party divisions. Institutional arrangements or policy commitments are supported by one party and entrenched in the constitution when that party is dominant, but they are opposed by the other party, which seeks to reverse them as soon as the opportunity presents itself. This desire to reverse constitutional commitments after a change in party control of state government has occasionally been sufficient to overcome legislators’ traditional reluctance to support conventions.

These various insights about the circumstances associated with calling conventions are helpful for addressing the question that is the focus of this article: why were conventions once called regularly? These conclusions can also shed some light on a question that attracts particular scholarly interest in the contemporary era: why are conventions called less often in the current era than in prior eras? The most important change over time is that public interest in and pressure to enact state constitutional changes to address challenges of governance were once sufficiently strong to be capable of leading and even compelling legislatures to call conventions. However, the current level of public awareness of state constitutions is minimal, as is the level of public confidence that concerns about governance are likely to be addressed effectively by changing state constitutions. Moreover, to the extent that members of the public make a connection between their concerns about governance and remedies in the form of state constitutional changes, this is less likely now than in earlier times to generate pressure to call conventions, in part because of the increasing availability of other mechanisms for changing state constitutions.