“Critical Regionalism is a dialectical expression. It self-consciously seeks to deconstruct universal modernism in terms of values and images which are locally cultivated, while at the same time adulterating these autochthonous elements with paradigms drawn from alien sources.”Footnote 1

In his seminal text that posits regionalism as a progressive, social form of modern architecture, Kenneth Frampton argues that self-conscious approaches to regionalist culture oppose a nostalgic vernacular that is built on emotive, sentimentalizing terms. Bound to a specific place, critical regionalism exists in the symbiotic relationship between intrinsically local and “alien” elements, which inform and shape each other, and creates forms that are locally engaged and modern. In contrast to a romanticizing nostalgic vernacular that is built on emotive, sentimentalizing terms, critical regionalism is an identity-giving culture “especially in tune with the emerging thought of the time.”Footnote 2 Frampton's is therefore a “productive” regionalism, which actively takes a part in the transformation of a delineated environment (“the region”) without losing touch with the wider world beyond. While the author clearly positions critical regionalism as a strategy against a universalizing late capitalist culture, its essence as self-aware anticentrism is pertinent to much broader considerations of the role of regions and regionalism in modern culture.

Using Frampton as a point of departure, this article interrogates the position of interwar Austrian painting outside Vienna, arguing that it deeply invested in the establishing of a “new” Austrian identity in which regionalism played a pivotal role. Set in a time and place where fundamental social and political changes were taking place after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire, regionalism served as a tool of adaptation in a new situation. Tracing this phenomenon, the article nuances an understanding of Austrian interwar culture split between Vienna and the “rest” of the country as rural backwater and shows that a modern artistic identity derived from the exchange between the city and the countryside.

The region is an entity understood here as a geographically rooted community as well as a political unit: Austria's nine federal states were formally established between 1919 and 1921 but had shared much longer histories and also included parts such as South Tyrol/Alto Adige, which were located abroad after 1918.Footnote 3 Regionalism, by extension, refers to the culture produced in and referring to a specific region, including rural areas such as Tyrol, but also Vienna. The city's unique position as interwar Austria's only metropolis meant that it certainly had an identity of its own, albeit one that was not quite seen to be compatible with the rest of the country. Led by a Social Democratic government, the achievements of “Red Vienna,” specifically, stood out in relation to social policies and housing reforms.Footnote 4 The city also remained the country's artistic center, with most exhibitions, galleries, and collectors, as well as academies and schools located there. However, while Vienna continued to be the place in Austria where one's reputation was “made,” its heterogeneous and metropolitan environment was hardly representative of the rural rest of the country, which formed the core identity of the new Austrian Republic.

After outlining how regionalism in painting rose to prominence in the First Austrian Republic, the essay assesses its role with particular reference to Alfons Walde (1891–1958), a painter and architect who worked in Tyrol between the world wars. Walde is a particularly interesting case to investigate the role of regionalism in modern Austrian painting after 1918: while there are several exhibition catalogues and biographical accounts of his work presenting him as “Austria's best-known painter,” Walde has never been subject to critical analysis in a wider context.Footnote 5 Indeed, his paintings more often appear as illustrations in assessments of tourism and alpine culture than in an art historical context.Footnote 6 The reason for this is that Walde not only represented a new direction in Austrian art at the time, which was appreciated in exhibitions and bought by private collectors and museums, but he also enjoyed a high degree of popularity in mass culture and his work regularly appeared on magazine covers and tourist posters. It would be rash, however, to do away with Walde as an artist who simply capitalized on the visual language of a popular vernacular. Rather, the active blurring of boundaries between high art and popular culture represented a central part of his practice as a visual artist. In doing so, his work revealed the decisive impact of modernity on local culture and, in turn, created a highly recognizable, new image of Austrian identity with mass appeal.

As the representative of a wider regionalist movement in Austrian interwar painting, Walde paved the way for a clearly identifiable image of Catholic, rural Austria without foregoing the modernization process that took place in the Alps at the time. Filtering essential elements of local culture and synthesizing them with both a modern formal language and “modern” topics, most significantly ski tourism, Walde created a regionalism that reverberated beyond the narrow confines of his home province. Indeed, the clearly defined typology of “Austrianness” in Walde's work caught particular momentum during the rise of the Austrian Ständestaat in the 1930s: celebrating Catholicism, rural culture, military pathos, and staunch patriarchal values, Walde's imagery seemed to anticipate the ideological specifications of the regime based on his construction of a location-specific modernity.

A “Lost Generation” of Austrian Art

Produced in and drawing inspiration from the provinces, Austrian regionalist painting had many facets after 1918 with varying levels of impact beyond their immediate locations. Regardless, the root of the upsurge in engagements with rural life had a joint cause: to reconnect with a local artistic culture as an act of rejuvenation, provoked by a sense of rupture in 1918 that was perceived in political as much as cultural terms. In lieu, the role of regionalism has been eclipsed by a much broader issue concerning the reception of Austrian art after and since 1918, following on from the glorious years of Vienna around 1900.

“It is symptomatic that almost every young artist stands or stood under Schiele's spell.… They continue his work through their work and crystallize it by their own specifications—Schiele has become the focus of contemporary art.”Footnote 7 Central to his assessment of Austrian art in 1923, this statement by the popular art critic Fritz Karpfen underlines that after Egon Schiele's early death of the Spanish flu in 1918, the artist quickly became a role model by which to measure those who succeeded him. To his contemporaries, this did not weigh in favor of his successors: characterized by a striking diversity in styles and a strong sense of caution toward artistic experimentation, Austrian art after 1918 was defined as a pluralist and undefinable post scriptum to the art of the previous decades. The artist Carry Hauser, for example, likened it to an exhibition “which makes it seem as if time had stood still since the turn of the century.”Footnote 8 Meanwhile, the art historian Hans Tietze, an enthusiastic supporter of the avant-garde, remarked in 1918, “from the point of view of the isolation that we got ourselves in and that made our artistic life much poorer than that of medium-sized German cities, there has arisen the wrong perception of local production; a terrible overestimation of outworn conventions as well as approaches to modernity.”Footnote 9

Eclipsed by an understanding of Vienna 1900 as the defining period of Austrian art, this positioning of interwar Vienna as an era of artistic drought continued long into the second half of the twentieth century, encapsulated in titles such as The Lost Austrians 1918–1938; Lost Modernity: The Hagen Artists’ Association, 1900–1938; and Uncertain Hope: Austrian Painting and Graphic Design, 1918–1938.Footnote 10 Only in more recent years, attempts to reconsider this perspective with the inclusion of previously understudied topics have taken shape.Footnote 11 Challenging the narrative of a male-centered Viennese modernism that “ended” in 1918, new research on the role of women in art and design, the position of Jewish artists and patrons, international networks, and role of the applied arts have begun to show interwar Vienna as a much more experimental, lively, and well-connected art scene than previously acknowledged.Footnote 12 In painting, for example, the classes taught by Franz Čížek at the School of Applied Arts led to the development of a dynamic group of young painters, including My Ullmann and Erika Giovanna Klien, whose Viennese Kineticism explored movement in painting by merging expressionist, constructivist, and futurist elements.Footnote 13 Nuancing the lamentations of contemporaries such as Tietze and Hauser, more recent exhibitions and publications such as Vienna: City of Women, Hagenbund: A European Network of Modernism 1900 to 1938, and The Female Secession show that Viennese interwar culture was, indeed, far from lost, and it continued to provide ground for artistic experimentation amid the reorientation process after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. Forming a parallel to these developments, the “discovery” of the provinces through regionalism forms another aspect of this process, albeit one that has been subject to much less critical attention.Footnote 14

The Dynamics of Interwar Regionalism

At a time when national identity had to be recalibrated, regionalism represented a vital aspect in formulations of the new Austria.Footnote 15 Yet, as Gunda Barth-Scalmani, Hermann Kuprian, and Brigitte Mazohl-Wallnig have suggested, “prejudiced by the nationalist traditions of nineteenth-century historiography, we have generally lent credence to nationally oriented historical explanations, thereby overlooking the fact that in many cases premodern structures remained active behind and under the surface of modern national identity.”Footnote 16 Focusing on two of Austria's westernmost federal states, Salzburg and Tyrol, the authors trace the growing significance of these regions after 1918 as powerful, identity-forming counterparts to Vienna. As the city was governed by Social Democrats in a state otherwise dominated by Catholic conservatism, Vienna no longer adequately represented the new state, leading to a growing importance of the rural provinces. There, new identities began to be reformulated, manifested with the founding of the Salzburg Festival in 1919, for example, which built on Salzburg's history as an archbishopric to transform the city into a bulwark for a Catholic, conservative, and German Austrian identity.Footnote 17

When the Ständestaat regime, led by Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß, rose to power in 1933/34, the rural conservatism that had developed as an alternative national identity became submerged in state ideology. While no overarching cultural program was promoted, the authoritarian government nonetheless endorsed a specific image of Austria: exclusively German, Catholic, rural, and rooted in folk traditions.Footnote 18 This led to increasing limitations in definitions of Austrian identity, accelerating a process that first started with the collapse of the Habsburg Empire and led to the exclusion of ethnic minorities, particularly Jews, from belonging to the new Austrian state. Regionalist painting represented a significant part of this development: visualizing central points of Ständestaat ideology with a focus on sublime landscapes dominated by patriarchal order and deep religiosity, it inevitably tied in with the culture of the new state, ultimately leading to its exclusion from broader art historical narratives. Eric Storm has rightly argued that one of the main reasons for this is, precisely, the role regionalism played during the authoritarian and fascist regimes of the 1930s and 1940s. After 1945, it was therefore seen as “an ideological forerunner of fascism and a negative, backward-looking force,” regardless of its diversity that came to the fore in the 1920s.Footnote 19 The simple and highly emotive visual language associated with regionalism's strongest facets in German-speaking culture, the popular Bergfilm, Heimatfilm, and Heimatphotographie genres, have tied it to a kitschy mass culture of little aesthetic value, impeding its presence in art historical discourse.Footnote 20 Adding to this, Austrian regionalism has been tied to its German counterpart in consideration of political developments in the 1930s, even though social and cultural conditions often differed until Austria's annexation to the Third Reich in 1938.Footnote 21

Moving beyond such interpretations shows that regionalist painting was a significant part of interwar Austrian art and visual culture, which promised a renewal in painting after 1918 and played a crucial role in defining national identity for the postimperial Austrian state. It not only reflected the country's new social and political setup as a homogeneous, small country but also had a wider impact on modern cultural developments overall than a focus on metropolitan centers alone can acknowledge. Indeed, while previously artists were drawn to Vienna, the years after 1918 saw the founding of artists associations in numerous regions of the new Austrian state: in August 1919, the newly founded artists’ association Der Wassermann (“Aquarius”) opened its first exhibition at the Künstlerhaus in Salzburg; the MAERZ group in Linz was reestablished in the same year; a local secession in Graz in 1921; the Nötscher Kreis in rural Carinthia in 1925; and the Mühlau Group in Innsbruck in 1919.Footnote 22

The founding of these groups was seen as a necessity for the creation of a new Austrian culture. Anton Faistauer, a former member of the progressive Secession offshoot the Klimt Group and close associate of Schiele, moved to Salzburg from Vienna in 1919 as a founding member of the Wassermann. His motivation was to find a new beginning, warning that after the war an “un-artistic, emotionless joke, has attacked Central Europe … and eats away at the heart of art, so that it will collapse if artists do not soon realize and return to the creation and the world itself.”Footnote 23 Considering Viennese traditions lost and the city too international to provide artistic guidance, Faistauer saw the only chance for renewal away from the city and within the return to rural origins.Footnote 24 For him, a pivotal feature of a renewed Austrian art was thus to be “at home” (“das In-der-Heimat-sein”), meaning that all forms of cultural production should be tied to their specific contexts as a means of renewal.Footnote 25 Regionalism therefore represented a necessary and productive force to secure the future of Austrian art after 1918.

Between Vienna and the Provinces

Within the wider tendency toward regionalism, Alfons Walde is a typical as well as an extraordinary example. Born near Kitzbühel in Tyrol in 1891, Walde studied architecture at Vienna's Technical University between 1910 and 1914, where he was particularly taken by the architect Max Fabiani's courses in ornament.Footnote 26 Yet Walde was generally more interested in becoming a painter than an architect. He soon began to move within central artistic networks of cultural life in the Habsburg capital: the Vienna Secession, its rival the Hagenbund, a moderate modernist league noted for its contacts to the provinces and abroad, and the Neukunstgruppe, a progressive artist league founded in 1909 by Schiele, Faistauer, and compatriots in protest of academicism. Supported by Fabiani and the architect and Secession president Robert Oerley, Walde quickly became part of these circles and, by 1913, participated in the 43rd exhibition of the Vienna Secession.

During his Vienna years, two artists had the most decisive impact on the young artist: Klimt and Schiele, whom Walde met as early as 1910, and who introduced him to the Klimt Group. Both artists closely shaped Walde's early artistic production. Crosses on Graves (ca. 1912; Figure 1) adopts the delicate pointillism that Klimt first used in his early work and continued to apply in his landscapes painted during summer vacation in the Salzkammergut lake district. Similar to works such as Klimt's Poppy Field (1907; Figure 2), Crosses is a square composition with a low vantage point, in which finely dotted lines evoke the glistening light of a bright summer day, setting the landscape in a glowing atmosphere. Given Walde's clear preference for Klimt's landscapes rather than his sought-after ornamental portraits that were all the rage among the haute bourgeoisie at the time, Walde chose to focus on a very specific set of techniques from Klimt's repertoire: the depiction of natural light on a clear day, which he would later remodel in his renderings of bright winter days in the mountains. Beginning with a simple process of copying Klimt's treatment of the natural landscape during his time in Vienna, Walde would thus strategically reduce his references to specific elements that complied with his own visions of the Tyrolean landscape.

Figure 1. Alfons Walde, Crosses on Graves, ca. 1912, oil on canvas, 70 x 69 cm, Tiroler Landesmuseum, Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Walde /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

Figure 2. Gustav Klimt, Poppy Field, 1907, oil on canvas, 110 x 110 cm. Courtesy of the Belvedere, Vienna.

The artist also took a similar approach to Schiele's painting. In Easter Sunday (1914; Figure 3) his confident, broad brushstrokes and freely applied bright colors are reminiscent of works such as City by the Blue River II (1911; Figure 4). Here, Schiele emphasized form through tonal contrasts, applied in a deliberately rough manner to create a dynamic atmosphere. Adopting these elements to his own specifications, the use of unblended bright colors and a confident roughness of form remained an elementary part of Walde's work in the years to come. Even though Walde's artistic emancipation became particularly striking after his return to Tyrol, references to his artistic roots in prewar Vienna remained.

Figure 3. Alfons Walde, Palmsonntag, ca. 1914, oil on cardboard, 28 x 30 cm, private collection. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Wald /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

Figure 4. Egon Schiele, City by the Blue River II, 1911, pencil, gouache and oil on board, 37.2 x 29.8 cm, Belvedere, Vienna, permanent loan from private collection. Courtesy of the Belvedere, Vienna.

While trying on different techniques and painterly styles in Vienna, Walde showed consistency early on in terms of content. His dominating subject was the Tyrol landscape and genre scenes from the region.Footnote 27 Noting that he had always preferred more tangible subject matter than the artists of the Klimt Group, Walde explained in an interview in 1925 that, “through Schiele, I also came to Klimt and his circle—but what was art to them was mystifying to me and I felt that it was time to return to Tyrol.”Footnote 28 With the advent of World War I, this took place both on an artistic and a physical level. After volunteering with the Tiroler Kaiserschützen infantry regiment in 1914, Walde only briefly returned to Vienna to obtain his diploma before settling in Kitzbühel, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Similar to other painters, such as Faistauer, Walde thus turned his back on Vienna after 1918. The artist's relocation went hand in hand with a shift in his painting practice, both in his motif choice and its treatment on canvas. Absorbing the formal experimentation of his Vienna years, he developed a trademark style of broad brushstrokes and thick color, creating abstracted, flat landscapes, always captured in the bright light of a clear alpine day. Directly linking the natural environment to his formal language, Walde's practice began to differ from that of other Austrian painters who swapped the city for the provinces at this time. Faistauer offers a notable point of comparison here. Not only did he move in similar Viennese circles as a founding member of the Neukunstgruppe but he also returned to his home province of Salzburg during the war and dedicated the first half of the 1920s to artistic production in the region.

Faistauer's contributions to Salzburg's cultural life are most evident in his involvement in the Wassermann group, and his fresco paintings for the Salzburg Festival Hall, for which he composed a series of bright religious scenes in the foyer, designed in line with the ideological specifications of the festival and Salzburg's historical position as an archbishopric.Footnote 29 Faistauer also painted the region, including Salzburg embedded in the mountains (Figure 5), as well as scenes from his close-by hometown of Maishofen.

Figure 5. Anton Faistauer, Salzburg Evening Landscape, ca. 1924, oil on canvas, 59 x 79 cm. Courtesy of the Belvedere, Vienna.

Aside from the recognizable views of Salzburg, Faistauer's works blend into a much broader practice of landscape painting in a soft form of expressionism that the artist developed as a young progressive in Vienna. There, he had closely engaged with the work of Paul Cézanne and continued his references to the French master until his early death in 1930.Footnote 30 Faistauer's attachment to Salzburg, meanwhile, was tied to selected motifs or, in the case of the fresco paintings, physical location. Thus, his references to Salzburg never come to the fore as an intrinsic part of his painterly practice so that his work overall could be described as “location specific.” Rather, the formal consistency of Faistauer's painting carries on from his prewar years in Vienna. As such, his move to the countryside did not have any formal consequences and instead underlines a strong continuity in his practice.

Based on this brief assessment, Faistauer represented Austrian regionalist painting in as much as he supported the creation of an independent Salzburg art scene with the Wassermann and his work related to the Salzburg Festival. However, this engagement had little grounding in his painting: staying true to a pan-European style, he adds no specific local character that would mark his Salzburg painting as a specific representative of the city's identity as the German, Catholic alternative to Vienna.Footnote 31

Painting (in) Tyrol, Painting the Alpine Republic

Walde took a more engaged approach to regionalism in comparison to Faistauer. He increasingly fashioned himself as a regionalist, noting in his diary in 1917: “I am a natural person, and simple and genuine. This is what my art must also be like, a mirror of the soul; I imagine, and I am convinced, that there are only few people with such modest characteristics and few artists of this nature. Thus, I hope not to become an average artist.”Footnote 32 Turning away from the city, Walde emulated the necessity to be “at home” with one's art, as Faistauer had put it, and tied his whole artistic production to its specific regional context after returning to Kitzbühel—all without foregoing his position as a modern artist. Walde's transformation from a young painter in Vienna in the shadow of Klimt and Schiele to Tyrolean Schneemaler (“snow painter”) was an orchestrated turn away from the “stale” city and a return to one's origins, the Heimat.Footnote 33 Simultaneously, Walde's navigating between essentialized depictions of local culture and modern artistic form also positioned his work against a nostalgic vernacular, as it was glorified in popular genre paintings by an earlier generation of Tyrolean artists, most notably represented by Franz Defregger (1825–1921).

While regionalism in Austrian art was widespread, the drive to define a locally rooted modernity never found as particular an expression as in Tyrol and in Walde's work. A particularly important aspect in this light was his ability to emphasize elements that embodied clearly identifiable themes of Tyrol and Austrian identity: the Alps and modern as well as traditional life within it. By limiting himself to these components, Walde's regionalism actively added to the transformation of the region as a distinct entity. In turn, Tyrol encompassed essential features of Austrian identity overall, its most significant elements being the alpine landscape.Footnote 34

The Alps formed an integral aspect of Walde's work. They featured in the majority of his paintings, which linked them to a broader cultural tendency in interwar Austria overall. In his review of the Internationale Kunstausstellung in Vienna in 1927, the moderate modernist critic Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven praised Walde's contributions to the exhibition as exemplary for Austrian contemporary art, referring to the artist as “an unusual force, of which we Austrians can justly pride ourselves.”Footnote 35 Ankwicz-Kleehoven particularly complimented Walde's Bergstadt II (1927; Figure 6), an image showing the artist's hometown dominated by the landmark towers of the Liebfrauen and St. Andreas churches. Bergstadt II is one of several paintings of Kitzbühel by Walde from the 1920s. While earlier versions resembled Schiele's brightly colored, dynamic images of the small town Krumau (today in southern Czechia), Walde's views of Kitzbühel from the mid-1920s show the town in muted earthy colors at a distance, seemingly uninhabited and calmly set against a backdrop of mountains covered in gleaming white snow.

Figure 6. Alfons Walde. Bergstadt II, 1927, oil on canvas, 179 x 199.5 cm, private collection. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Walde /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

Frozen in time, this version of Kitzbühel was far removed from the busy tourist hotspot it already was at the time: by 1925, the small town had risen to prominence as an upper-class skiing location among wealthy Austrian, German, French, and British tourists. A world away from the isolated town in the painting, Kitzbühel was a busy location in the winter months, connected to public transport links and buzzing with cafés, restaurants, and luxury hotels. Moreover, in 1925, the town's traditional white facades had been painted in bright colors upon Walde's own suggestions:Footnote 36 he was Kitzbühel's municipal planning officer at the time.

Bergstadt II shows an altogether different image. It focuses on an impression of Kitzbühel immersed in the vast alpine landscape stretching out in the background. The thick paint applied on the canvas with coarse brushstrokes echoes the textures of the mountains in the snow. Only the two church towers add a sense of monumentality to the otherwise small, sheltered village. The dominance of the towers also emphasizes the strong Catholic traditions prevailing in the region, which not only formed an essential part of Tyrolean culture but also played a pivotal role in forging an exclusive German–Austrian identity in the course of the interwar years.Footnote 37 With the busy jet-set town rendered as a place lost in time, Bergstadt II thus makes way for an impression of the Alps, which not only represented a leitmotif in Walde's painting—the present example is one of four oil paintings of this same view of Kitzbühel created in 1927/28 alone—but also emphasizes the essence of a region coded as a central part of the Austrian national landscape after 1918.

The reinvention process of the Alps began during World War I, when the region's image as a slightly backward yet idyllic holiday land made way to scenes of intense fighting and adventurous warfare on high mountain peaks.Footnote 38 Subject to widely circulating reports in the press, illustrated by war painters and photographers, the battle scenes in the mountains gained attention as particularly treacherous and heroic sites of conflict. Moreover, regiments that specialized in mountain warfare, such as the Tyrol Kaiserschützen, quickly rose to prominence as war heroes and adventurers who were predestined, not disciplined, to fight.Footnote 39

Walde had himself rejected offers to become a war painter, but during his time as a Kaiserschützen volunteer recorded his experiences in photographs and paintings. The latter found great appeal in commemorative culture after the war. In 1923, the artist was commissioned to decorate the facade of the Kaiserschützen Memorial Chapel in Innsbruck (Figure 7). Designed by the architect Clemens Holzmeister, one of Austria's main representatives of conservative modernity in the interwar years, and executed by the Kaiserschütze and architect Theodor Prachensky, the chapel is a simple design with a clean facade and pointed arch at the center. Walde's mural frames the archway with two larger-than-life Kaiserschützen. One a decorated officer, one an ordinary soldier, they look in opposing directions propped up on naked rock.

Figure 7. Clemens Holzmeister, Theodor Prachensky, and Alfons Walde, frescoes, Kaiserschützenkapelle, 1922. Photo courtesy of Ing. Hans Zimmermann, Innsbruck.

Rather than individuals, the men represent archetypes of a militarized masculinity, with broad shoulders, muscular legs, and angular features, evoking impressions of strength, perseverance, and control. The depiction thus mutes the traumata of mountain warfare in favor of unabridged heroization, in which men act with cool self-awareness in defense of their country. That the public welcomed such stylizations is evidenced by the fact that Walde's anonymous Kaiserschützen soldiers quickly gained popularity and were published in almanacs and commemorative soldier's yearbooks.Footnote 40 Circulating as cheap prints, Walde's work from this time onward gained great visibility and first manifested his position as an artist who was closely acquainted with Tyrol's mountainous terrain and their heroic conquerors. As Chancellor Dollfuß was a decorated Kaiserschützen soldier, Walde's iconic depictions of soldiers gained particular attention in line with the ideal masculinity promoted by the Ständestaat in the 1930s, which is addressed in detail in the text that follows.

Fueled by news reports of heroic acts of patriotism and a rich imagery by soldier-artists, World War I transformed the alpine landscape from a place of leisure to a symbol of trauma, but also of action, persistence, and masculine strength. Aside from Walde, a similar image was cultivated by fellow artists such as the Tyrolean painter and Secession member Albin Egger-Lienz, as well as Stephanie Hollenstein, a Vorarlberg painter with fascist political leanings who served in the Standschützen regiment disguised as a man.Footnote 41 After the war, memorials located in the Alps were well-visited, and tourist officials soon planned for visits to war memorials and cemeteries as a new branch of postwar tourism. Anticipating the development of the hero cult, one overenthusiastic travel agent in Karl Kraus's The Last Days of Mankind (1918) remarks: “We are hopeful that pious visits to the graves of heroes and war cemeteries will result in a lively tourist trade.”Footnote 42

The strong coverage of soldiers as “heroes in the mountains” not least led to a rise in popularity of mountaineering clubs in the immediate postwar years. Between 1919 and 1923, memberships in the Austrian Alpine Club (Alpenverein) tripled and counted 250,000 members by 1924.Footnote 43 More than just an “imagined” landscape, therefore, the popularity of the Alps after 1918 became an integral part of the Austrian economy, celebrated as a lived experience, whose position as a national landscape was closely tied to its new accessibility through mountaineering clubs and touristic ventures.Footnote 44 Particularly in Tyrol and in lieu of alpine clubs, this landscape also became increasingly exclusive: as Lisa Silverman has outlined, hiking clubs saw the introduction of anti-Jewish policies (Arierparagraphen) as early as 1921, coinciding with the blaming of Jews for the loss of the war.Footnote 45 Closely tied to models of German-Catholic identity, the Alps thus also anchored reactionary politics in the national landscape. They embodied the exclusive image of a “German–Austrian” idyll, which not only persisted easily throughout World War II but also featured strongly in the recovery process of Austrian national identity after 1945.Footnote 46

Further to their central position during World War I and in its immediate aftermath, the symbolism of the Alps as the national landscape was heightened by postwar territorial changes. As Austria shrunk from a large multinational empire to a small nation-state of six million inhabitants in 1918, the Alps suddenly occupied two-thirds of the state territory. In the Baedeker travel guide to Austria (1926), this change in situation was presented as both a curse and a blessing: “the diverse empire with its rich treasures and colourful, all too colourful mix of people became a much poorer state mainly delimited to the Alps and only including few prosperous areas, but also became nationally much more unified in its social and cultural structures.”Footnote 47 As a small entity that increasingly emphasized a homogeneous German-Catholic identity, the new Austria was a state in which the Alps represented “a constitutive part of Austrian society and culture.”Footnote 48 The alpine landscape seemed to contain a host of factors that were essential to the new state. Portrayed as a challenging, rough environment, it offered a recourse of strength, which the writer Hermann Bahr, an early supporter of the Secession who turned toward conservatism in the interwar years, described as “male, forceful and thoroughly German.”Footnote 49 Rather than representing the effeminized safe haven that Heimat was traditionally connoted with, the Alps signaled rejuvenation, particularly in comparison to Vienna, which the popular press interchangeably personified as “Jewish,” an amputated veteran (Figure 8), or a prostitute dependent on the benevolence of foreign suitors.Footnote 50

Figure 8. Josef Danilowatz, “Refurbished Austria,” Die Muskete 36, no. 3 (20 Jan. 1923): 1. Courtesy of the Austrian National Library, Vienna.

In Bergstadt II, Walde's Kitzbühel as a timeless citadel in midst of the mountains evokes a strong sense of the way in which the Alps symbolized the new country's natural strength and protective force. As one of a series of images that focused on quaint Tyrolean villages and mountains covered in soft snow, Walde essentialized the alpine landscape and transformed it into a widely recognizable symbol. Ostensibly removing all traces of modern life, Walde's landscapes offered an image of the new Austrian Heimat, which resounded both with a broader perceptual change of what represented the national landscape and the search for modern artistic form.

Color, Form, Surface: Regionalism as a Language of Modern Art

Emphasizing the artist's turn toward “clean” forms and colors, contemporary critics tied the formal simplicity of Walde's landscapes to a modern art that not only harmonized with the simple strength of the Alps but also derived from it. Artistic renewal was seen to emerge directly from the artist's ties to the landscape: “Alfons Walde creates, surrounded by the majestic beauty of his mountains, in the quiet solitariness of a small village, and from all his work flows the austere beauty of his Heimat,” Karpfen described the artist's work for Bergland in 1924.Footnote 51 Far from backing the reactionary ideology of “blood and soil” that such a statement may evoke, Karpfen was a liberal progressive writer of left-leaning political convictions, who had championed Walde's work since the early 1920s.Footnote 52 In multiple reviews and his multivolume account of contemporary art in Europe, Karpfen presented Walde as the promising successor of Austrian “masters” of the previous era, most notably Schiele, and as a national artist, whose work assured authenticity through references to local (alpine) conditions.Footnote 53

The author of Der Kitsch: A Study of the Degeneration of Art (1924), Karpfen saw Walde's work as the diametrical opposite to kitsch, which he defined as “a mixture of the secession, oriental colors, rustic woodcuts, a childish-naïve feeling for composition and acrobatic acts that could derive from a circus.”Footnote 54 While he does not name the artist directly, instead focusing on Walde's close associate, sculptor Gustinus Ambrosi, Karpfen's understanding of “modern art proper” to “contain simply three things: color, form, surface” closely corresponded with Walde's paintings, categorizing them as an ideal art of a new era.Footnote 55 Rather than lamenting that there was no Austrian avant-garde, as was the position of critics such as Tietze, Karpfen thus held a different point of view: the reorientation of Austria as a small, homogeneous nation-state demanded the reorientation toward an art that could reflect this.Footnote 56

As Walde's shift in visual language toward simplified shapes and bright fields of singular color coincided with his return to Tyrol, contemporaries such as Karpfen understood his work in line with its region of production. Compared to Faistauer, who included aspects of Salzburg but never forged a link between his work and the region, Walde embedded his paintings in the region in content and in form. Simultaneously, he upheld a drive toward formal innovation compared to his work from earlier years. Walde's practice thus offered a traceable shift, which coincided with the historical break in 1918 and thus appeared to contain a distinct move toward a new artistic direction in response to a new, republican Austria.

The Alpine People: Austria as a Land of Catholic Farmers, Climbers, and Skiers

In addition to the Alps as a central source of inspiration for Walde's modern regionalism after 1918, the artist constructed a tight image of those who inhabited and visited them. His regionalism also pertained to the creation of specific people “types” connected to Tyrol. Broadly speaking, these could be divided into a “native” population—local farming communities and villagers—and the “visitors,” an urban, bourgeois clientele who spent summer or winter holidays in the mountains. These types had populated Walde's landscapes since his beginnings as a painter in the 1910s. By and large, they reflected Tyrol's dual significance as “holiday land” and “rural backwater,” which had informed the region's characterization since the late nineteenth century. In the Austrian Republic, this image gained renewed currency: aside from representing a new national landscape, the Alps bore the potential to modernize and expand an already existing tourist industry. While central locations of prewar tourism had fallen to Italy with the partition of Tyrol in 1918/19, the combination of an ailing Austrian economy and remaining picturesque locations made the region an affordable holiday location for the budding middle classes.Footnote 57 By the mid-1920s, the Tyrolean tourist industry had thus become an essential part of the national economy.Footnote 58 The figures in Walde's paintings closely traced this development, visualizing “Austrian people” in close association with Tyrol's centrality for the economy and the search for the “new human.” This is particularly visible in relation to the construction of male archetypes after World War I, who represented the ideal human of a new era on both sides of the political spectrum.Footnote 59

Walde's regionalism was all-encompassing and offered a strong sense of continuity between traditional rural life and modernity, doubly enforced in his treatment of human figures in front of the alpine landscape. Walde's farmers, ski tourists, and alpinists gained a more definitive style in the early to mid-1920s, coinciding with the recovery of Tyrol as a touristic region of international renown after the war.Footnote 60 As Walde was closely confronted with these changes as the planning officer in Kitzbühel, his reworking of these figures at precisely this point in time hardly seems coincidental. Rather, they consolidate in line with a slow manifestation of what and who “Austrians” (Austrian men in particular) were in the broader cultural sphere.

From the beginning of the war until the early 1920s, the dominating figures in Walde's work were Kaiserschützen soldiers. With the war casting a long shadow on Austria, heroic images of anonymous soldiers alluded to battles in which men fought one against one, juxtaposing the gas and automated machine gun horrors of modern warfare.Footnote 61 As muscular men standing tall on barren stone, Walde's soldiers supported this apposition with natural figures of masculine strength.Footnote 62 Yet Walde also translated this hypermasculinity to civilian settings in images of farmers and alpinists. In iconic works, such as (Top of the) Peak (1928; Figure 9) and Farmer's Sunday (1927; Figure 10), strong male figures pose in a landscape composed of stone, snow, and a bright blue sky, which echo the simplicity of the figure's own depiction.

Figure 9. Alfons Walde, Gipfelrast am Pengelstein, 1928, oil on canvas, 78 x 100 cm, Museum Kitzbühel. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Walde /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

Figure 10. Alfons Walde, Bauernsonntag, 1927, oil on cardboard, 52 x 39.8 cm, Museum Kitzbühel. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Walde /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

The farmers and alpinists rarely follow specific activities. They are not shown in action, but observe their environment in peace, suggesting an element of control at their hands, which allows them to survey and to contemplate. In conjunction with the men's physiognomy, their positioning within the landscape implies a set of character strengths that the Alps were seen to evoke. In his cultural history of Tyrol (1904), the historian Franz Arens emphasized, “people from the mountains are different than people from the plains.”Footnote 63 Secluded from the outside world through geographical conditions, he saw them to be rougher and closer bound to age-old traditions, stronger due to physical demand, and less influenced by “ambition, social achievement and the reckless abuse of social inferiors than people in modern society.”Footnote 64 While Arens referred to native inhabitants of Tyrol exclusively, Walde's visual interpretations opened up this interpretation to include not only farmers in the mountains but also those who conquered the mountain peaks. Encompassing both the image of the rooted farmer and the anonymous adventurer, Walde's images assert that the mountains turn men into pictures of health and strength. Images such as Peak and Farmer's Sunday not only glorified the alpine setting as an ideal environment to cultivate masculine strength but also promised an elevation of character.

Debates about the conjunction between the alpine landscape and specific physical and mental characteristics were long established in the 1920s and rooted deeply in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 65 Yet in the small Austrian Republic after 1918, they gained national significance. Just as the Alps became the Austrian national landscape, so did life within it promise improvement. Building on ties between landscape and character, the alpine regions bore the potential to bring forth the better “Austrians.” The dark side of these ideals quickly became visible in steps toward policing who was allowed to spend their holidays in the Alps: by the mid-1920s, the first towns began to declare that Jewish holiday-makers were not welcome. As “Aryan holiday towns,” such places provided a stark contrast to those such as Bad Ischl and Bad Gastein, known as “Jewish” places for holiday-making.Footnote 66 The new “Austrians” who could seek strength from the mountains in Tyrol epitomized an ethnic German identity, narrowing down the possibilities of who could claim an Austrian identity and who would forever be an outsider.Footnote 67 Regardless of Walde's personal convictions, his highly stylized treatment of the human figure as pictures of rural strength easily fit within these exclusive notions of Austrian identity, owing not least to the idealization of Tyrolean simplicity that formed the core of his painting style.

While the ethnic possibilities of being Austrian were increasingly limited, the new national identity blurred previously established boundaries of identity in other respects—specifically, the division between the city and the countryside. Walde's work addressed this in his depictions of alpinists. While the farmers in his paintings were rooted in the alpine environment as the native population, the alpinists included visitors and locals alike. They visualized the possibility of finding one's strength in the mountains for an urban segment of the population, appealing to a growing enthusiasm for ruralism and folk culture in the city.Footnote 68 Paintings such as Peak thereby anticipated the promise of the Alps as the “true” place of belonging (Heimat), popularized in cinemas with the Bergfilm genre from the late 1920s onward. Offering adventure, love, and physical and mental challenges, and ending with the realization that home is best, films such as Arnold Fanck's famous The White Hell of Pitz Palu (1929), starring a young Leni Riefenstahl, and The Prodigal Son (1934), written and performed by the actor and alpinist Luis Trenker, constructed a popular ideal of the mountains as modern and timeless, threatening and comforting at the same time.Footnote 69 The elitist image that skiing and alpinism had had at the turn of the century made way to an image of alpine sports open to “everyone”—providing that they fit into the new ethnic limitations as “Austrians.”Footnote 70 Walde's use of a pared-down visual language in figure and landscape thus followed a visualization of the mountains as a social equalizer. Projecting a classless society in which man only had to face nature, he tapped into a romantic yearning for the countryside that was central to the touristic image of Tyrol and the reinforced conception of the new Austrians as nature-loving, devoted, and strong Germans.

In their physical features, Walde's farmers and alpinists corresponded with a wider pictorial trend, in which hypermasculine civilians on advertising posters and Bergfilms implied the continuing dominance of military ideals for male role models. The transformation from Kaiserschütze to farmer thus went in hand with the development of the ideal worker figure in popular culture across the political spectrum; all implying that strong and hardworking men could take up arms again at any moment to fight for their cause.Footnote 71 Beyond these broader associations of the masculine man in interwar visual culture, Walde's farmers and alpinists gains particular significance in relation to the Ständestaat. After the regime was established in the early 1930s, Austrian society experienced a crass remasculinization, which actively pushed women out of public life through a series of new laws and reinstated a patriarchal order whose gender roles were even less flexible than those of the National Socialist regime.Footnote 72

Two aspects were particularly central to the Ständestaat cult of masculinity: the heroization of fallen soldiers and the celebration of the farmer as the ideal man living in organic harmony with the homeland and (a Catholic) God.Footnote 73 Indeed, in a speech held in June 1934, Chancellor Dollfuß directly asked, “Who could be closer to nature, who could follow the natural laws of economic cohabitation more closely than the farmer?”Footnote 74 Given Walde's focus on rural farming communities and Kaiserschützen soldiers since the early 1920s, his paintings corresponded with the ideals of the new government; all the more so, as his formal language linked these communities to the contemporary and thus visualized the symbiosis between modernity and tradition that the Ständestaat represented.Footnote 75 Suggestive rather than concrete, the abstracted shapes of his figures served as a projection surface for the nature-loving new Austrian. Portraying a strong masculinity that formally derived from the image of Kaiserschützen soldiers, Walde's farmers and alpinists thus encompassed the Janus-faced nature of the alpine landscape, which essentialized the conflicted tendencies of interwar Austrian culture, particularly in the 1930s: embracing modernity, it never cut loose its deeply conservative ties.

Romance in the Alps

Walde's regionalism not only visualized the new Austrian landscape but it also populated it with ideal inhabitants. The essentializing of the region as a place of “modern tradition” also encompassed the topic of gender and interhuman relationships. Returning to Bahr's description of Tyrol as “forceful and masculine,” Walde's figures characterized the region as a masculine place: women are present, but strictly framed by the male gaze as erotic alpine nudes or busty farmer's wives and mothers, whose soft, rounded shapes juxtaposed the jarred, angular forms of their male counterparts. Similarly, female skiers often feature as curvaceous silhouettes or a pair of well-shaped legs on display (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Alfons Walde, Dame beim Schianschnallen, ca. 1927, oil on cardboard, diameter 26 cm, private collection. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Walde /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

Carrying an erotic charge, they insinuate a promise of clandestine promiscuities, which was part of the romanticism established around alpine tourism following the proverb “Auf der Alm gibt's koa Sünd” (“there is no sin on the mountains”).Footnote 76 Indeed, Trenker, one of the biggest international stars of alpinism in the 1920s and 1930s, dedicated a special subchapter in his popular book Mountains in the Snow (1932) to women and skiing, emphasizing the role of romance on skiing holidays, particularly for the male participant.Footnote 77 Similarly, the dominant point of view in Walde's work is male and follows a strictly patriarchal worldview. More than just a male fantasy, however, the social structures on display were still the norm in rural areas: even though gender roles slowly changed in the cities before the policies of the Ständestaat set in, rigid social structures in the provinces barely changed between the wars.Footnote 78

Depicting these conventions in his paintings uncritically, Walde reinforced the image of a region in which traditional values were upheld. With clearly delineated relationships between the sexes, works such as Soldier on Leave (1928; Figure 12) construct an ordered society in which essential aspects of human life and relationships seem static and unchanging. Once more, these visualizations played into the hands of the Ständestaat ideology. Since the mid-1920s, figures such as Guido Zernatto, secretary of the government's Fatherland Front party and author of books such as The Farmer (1925–27), developed a rustic, patriotic pathos in which farming communities represented an eternal, ideal, and natural way of life, which could “heal” the turbulences of modern society—so much so, in fact, that Zernatto presented them as models for the perfect state.Footnote 79

Figure 12. Alfons Walde, Auf Urlaub, ca. 1928, oil on cardboard, 26 x 22.5 cm, private collection. Courtesy of Kunstverlag Alfons Walde /Bildrecht Wien 2020.

The Alps, in this light, were two worlds combined: one modern and economically important, the other archaic and traditional. While they did not meet on Walde's canvas directly, the world constructed in the paintings overall enforced a sense of stability, which grounded his regionalism in a masculine ideal of strength and authenticity and promised an assertive and new Austrian identity. In light of Tyrol's central position in an Austria increasingly defined by a culture of nostalgia, alpinism, and a rural landscape, Walde's Tyrolean types did not remain confined to their context of origin but, like the Alps, quickly grew in national significance. Not least, the transformation from what was initially conceived as “Tyrolean” regional to becoming “Austrian” related to the circulation of and response to the work of Tyrolean artists in Vienna and abroad. Growing in popularity in the mid-1920s, this cultivated a new image of Austria, which could readily be absorbed by the Ständestaat in the 1930s.

The New Austria on Display: Circulation, Affirmation, and Exchange

With the Tyrolean mountains and life within them as his dominant subject, Walde tapped into a broader enthusiasm for the Alps in Austrian culture, connected to the slow recovery of the Austrian economy in the mid-1920s in which alpine tourism played a considerable role. In established art institutions, as in popular culture, this enthusiasm became apparent in a growing number of exhibitions, which positioned the Alps as an intrinsic region of the Austrian Republic. A central exhibition in this context was Tiroler Künstler (1925/26), in which contemporary artists from Austria's western province showcased their work. As a group exhibition, Tiroler Künstler conceptualized the alpine landscape as the source of a particular artistic culture, taken up in a review in Österreichische Illustrierte Zeitung, for example:

In the first instance, it seems inappropriate, wrong even, to categorize creative work based on geographic or regional aspects. In art history we do not know a Styrian, nor a Bavarian or a Prussian art, but only the monumental oeuvre of a German art, which has regional idiosyncrasies just like language has its dialects. And yet we can speak of a Tyrolean Art, because this mountainous borderland between two peoples and two cultures, in which Etruscan-Roman Elements penetrate from the South and heavy Germanness from the North, maintains such idiosyncrasy, such obvious individuality, that it does not come off simply within a general German art.Footnote 80

Touring a number of German cities, including Düsseldorf, Hamburg, and Munich, Tiroler Künstler presented the Alps as a pivotal element in shaping a specific regional art, which quickly came to bear the hallmarks of new Austrian culture at large. After a successful German tour, which sold more than one hundred of the two hundred works exhibited, Tiroler Künstler was shown at the Secession in Vienna before traveling to Budapest in autumn 1927, and, in spring 1928, to Zurich. In 1927, the thematic exhibition Die Alpen im Bilde (“the Alps in view”) at the Künstlerhaus, collaboratively organized with the Alpine Club, showed a similar range of artworks, including a series of Walde's works, who was overall well received in reviews throughout the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 81

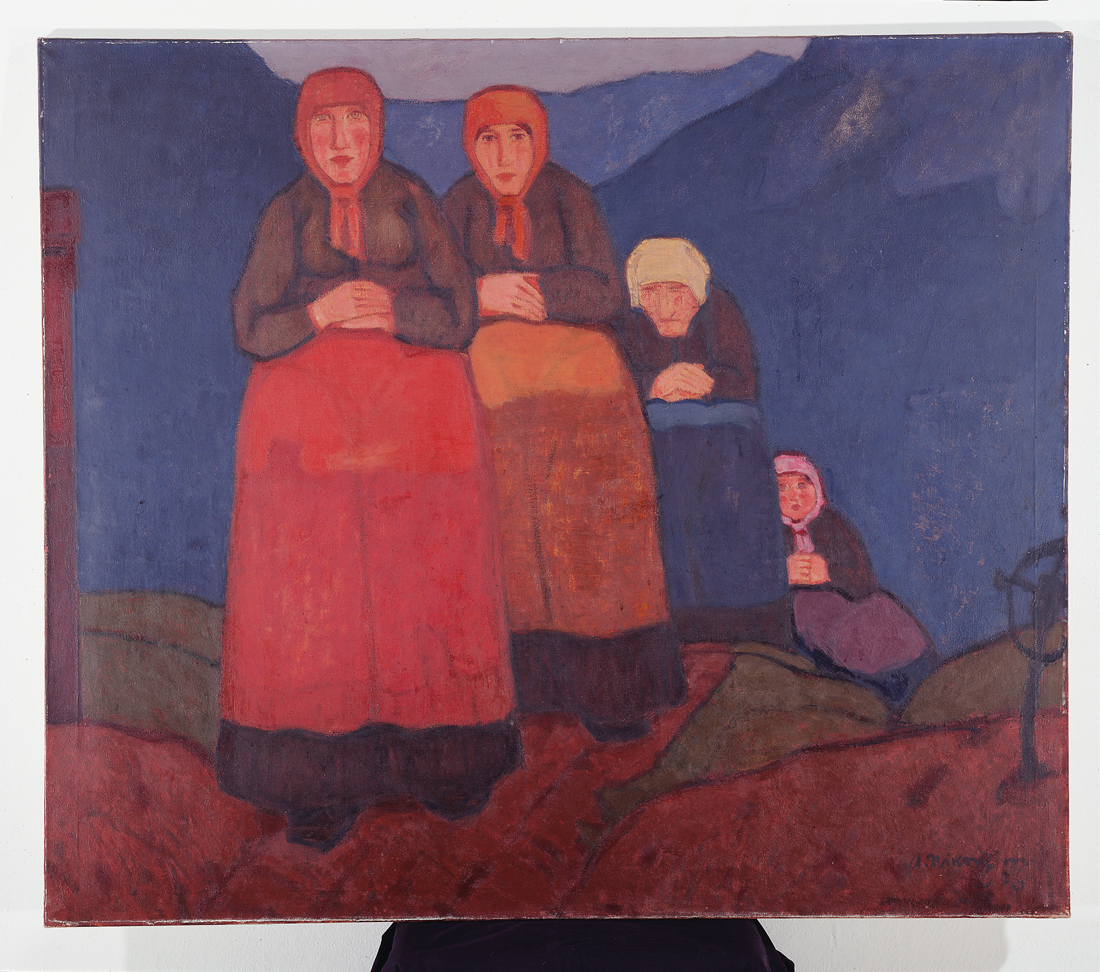

Aside from Walde, well-known Tyrolean regionalists included Egger-Lienz, the New Objectivity painter Ernst Nepo, and the painter-photographer Artur Nikodem.Footnote 82 Though not all these artists referred to the alpine landscape quite as extensively as Walde, the life and culture in the Tyrolean mountains, shown in monumentalized simplicity, represented a central point of reference throughout their work. Contributions such as Egger-Lienz's Ploughman (1920; Figure 13) and Nikodem's Pilgrimage (1926; Figure 14) displayed a similar formal simplicity that also stood at the core of Walde's painting. This not only places Walde within a genealogy of Alpine painters that made their name as representatives of interwar Austrian painting but also shows how large-scale flat fields of color and formal simplicity became closely tied to the pictorial representation of the alpine landscape.

Figure 13. Albin Egger-Lienz, Ploughman, 1920, oil on canvas, 109.5 x 129 cm. Open source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AEL_Der_Pflueger.jpg.

Figure 14. Artur Nikodem, Die Wallfahrt, 1926, oil on canvas, 125 x 145 cm, inv. no. Gem/203, Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck. Courtesy of Tiroler Landesmuseen.

Widely acknowledged as the “founding father” of modern painting in Tyrol, Egger-Lienz declared in 1925, “I do not paint farmers, I paint forms.”Footnote 83 Walde, meanwhile, quoted Paul Gauguin in his diary, noting, “the artist should not copy nature but instead take elements from it and create a new element with them.”Footnote 84 This reduction of alpine culture to its essence in content and form emphasized by the best-known artists from the region was not understood as the decision of the individual artist however, but as an innate feature of Austrian alpine painting. Writing for the conservative Reichspost, the critic Viktor Trautzl remarked, “Tyrolean artists bring us a piece of splendid nature and unspoiled strength, much more goal oriented and secure than the painters of the metropolis.”Footnote 85 The liberal Die Stunde, meanwhile, concluded, “the exhibition of a region without a metropolitan center, with nothing other than unspoiled strength, which has been obstructed in so many ways, and burst in so many directions, is surprising—it reveals that part of the Austrian character, that despite bad conditions, can, all of a sudden, accomplish so much.”Footnote 86 The authenticity that derived from a return to the “local” environment thus offered assurance that strength could be gained from “within” the country, rather than trying to catch up with cultural developments elsewhere.Footnote 87 In other words, the particular character of modern art ascribed to the alpine region promised national renewal, and thus represented a yearned-for solution for a new Austrian art after a period of uncertainty.

However, despite the importance ascribed to the region, it was the interplay between countryside and metropolis that constructed regionalism as a form of rejuvenation of Austrian culture. For even though Tyrol might have been a region of particular authenticity, it was its acknowledgment in Vienna that made this a cultural fact of note. Affirmed in press reviews and bolstered by a wide image circulation in popular entertainment culture, the alpine region at the heart of the new Austria thus developed through a process of transfer and exchange, in which regionalism was an integral part of modern cultural identity. Once more, Walde serves as a case in point here, both regarding his professional development and network, and the significance of his work as national representation between high art and popular culture.

Introduced to the main representatives of Austrian prewar painting as a student in Vienna, Walde's career started in the Habsburg capital, like that of many other artists of his generation. There, Walde made contacts that permanently set his work into a network between Tyrol and the city, where it was exhibited, discussed, and bought. The two most significant figures in this regard are Holzmeister and Ambrosi, who held significant cultural posts in the Ständestaat and consistently supported Walde with representation in exhibitions and other cultural projects.Footnote 88

With the Tyrolean town Kitzbühel as a favorite among a cosmopolitan clientele, Walde, indeed, was far from an isolated provincial artist. By the mid-1930s, the painter had become a socialite who regularly invited Viennese and international guests to his Berghaus on the Hahnenkamm, featuring in society magazines and newspapers alike.Footnote 89 The artist's work was in great demand, and while Walde founded his own publishing house in 1923 to protect the copyright on his work on postcard and poster sales, a scandal erupted in 1937 when an artist's studio in Vienna was found out to specialize in forgeries of Walde's work.Footnote 90 Standing at the forefront of modern regionalist painting in Austria after 1918, the popularity and mass circulation of his paintings surpassed that of other artists working in this tradition. Further evidence for this can be found in the exchanges between Walde and Ambrosi, who occasionally managed Walde's painting sales in Vienna. In 1927, Ambrosi wrote to Walde, “people are talking that you paint hundreds of paintings on cardboard. This only harms you, dear friend. You will never receive a [proper] price for your paintings in this way and will have to work hard forever!”Footnote 91 Two years later, another warning, “they say: the painter Walde is very good, but he paints the same subjects on cardboard by the dozen and also sends his work to substandard premises in Bad Gastein.”Footnote 92

Contrary to Ambrosi's concerns, the wide circulation of images, which Walde further supported with contributions to Viennese magazines such as Die Muskete and Die Bühne, book illustrations, and posters for the Tyrol tourist board, only widened the artist's influence.Footnote 93 Given the simplification of visual forms that stood at the heart of Walde's practice, his graphic work organically merged with his painting, creating a recognizable and unified style that even brought forth definitions such as the “Waldetag,” referring to a bright winter day with perfect weather conditions.Footnote 94 Navigating the presentation of his work between Viennese artistic circles and in the popular media, Walde created an image of a regional yet modern Austria that reinforced the country's new identity in simple terms through consistency and repetition.

Conclusion

With the founding of the Austrian Republic in 1918, the parameters for a new national culture were established only slowly. Indeed, it only took more definitive forms with the advent of the Ständestaat in the 1930s, when a reactionary conservatism cultivated the ideal of a deeply Catholic, patriarchal, and rural Heimat reserved for “German–Austrians.” However, the example of Walde's painting shows that the regional modernity cultivated by the regime had really begun to develop in the early 1920s and was closely tied to the search for new artistic directions after World War I.

At a time when painting was in crisis, eclipsed by the deaths of prominent Viennese artists such as Klimt and Schiele, regionalism seemed to offer rejuvenation and an alternative engagement with modern art compared to that of the city. Nowhere was this more visible than in Tyrol, where Walde developed a particularly engaged form of modern regional painting. Having moved from Vienna to Kitzbühel just after the end of the war, the artist developed a visual language that responded to the search for a new Austrian identity. Rooting his work in its region of production, Walde not only focused on visual content that essentialized important aspects of Tyrol as an agrarian and touristic region but also developed a formal language that emphasized characteristics that were historically ascribed to Tyrol and its inhabitants. Simultaneously, he presented the region as a modern setting in reference to ski tourism. In doing so, Walde's Tyrol was not an isolated province but engaged in steady exchange with wider Austrian culture, which was also pertinent to the circulation of his own work. Offering simple visual solutions to central aspects of a new Austrian culture, Walde thus responded to local conditions of national significance.

The key to his formula was the careful nuancing between elements of modern culture and traditional conventions, which promised a new era of Austrian art without rejecting the past. In the reorientation process from monarchy to nation-state that haunted Austria throughout the interwar years, Walde offered a new visual culture that ostensibly built on the transformations that the country underwent after 1918. The way he “tried on” elements of painting by Klimt and Schiele before consolidating his own style upon his return to Kitzbühel, Walde visibly followed the shift from empire to nation-state. As such, his work offered a new direction in Austrian painting after 1918, which closely built on a dialogue between the past, local specificity, and modern approaches. With a succinct repertoire of the alpine landscape, Walde linked his painting to formulations of interwar Austrian identity like no other. When regionalism took a one-dimensional political shift in the 1930s, this also meant that Walde's work could readily be adopted into the repertoire of Austrian identity endorsed by the government: with images of the alpine landscape, farming communities, ski tourism, and Kaiserschützen soldiers, Walde's regional modernity visualized fragments of society that were idolized in the Ständestaat and—at least to some extent—still relate to visualizations of Austrian rural identity today.Footnote 95 Moving in between regional and national significance, Walde's work underlined the essential position of the region in Austria after 1918. More importantly still, it also conveys that an engaged regionalism that responded to the rapid cultural and political changes taking place, did, indeed, become one of the most significant forms of interwar Austrian painting.