Exposure to childhood adversity is associated with maladaptive developmental outcomes, including the emergence and persistence of psychopathology (Green et al., Reference Green, McLaughlin, Berglund, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2010; Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009). Research is beginning to show that adversity may become biologically embedded by affecting brain development via stress-related processes (McEwen, Reference McEwen2012), with recent emphasis on the effects of adversity within the caregiving context (Callaghan & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan and Tottenham2016). However, much of this work has focused on extreme features of caregiving (e.g., childhood maltreatment, early institutionalization), rather than how more common forms of adversity within the parent–child relationship, such as harsh parenting, may be related to brain function. Moreover, although prominent theories (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015) have emphasized that different brain regions mature at different rates and, thus, may be more or less sensitive to adversity during different developmental periods, little work in humans has tested how the timing of adversity modulates its effects on brain function. Thus, more research is needed to examine how and when harsh parenting affects later brain function, particularly within neural regions key to stress responses and socioemotional functioning.

Harsh parenting across childhood

Harsh parenting is characterized by high intrusion, coerciveness, and physical or verbal aggression (Bugental & Grusec, Reference Bugental, Grusec, Lerner and Damon2006; Darling & Steinberg, Reference Darling and Steinberg1993; Tamis-LeMonda, Briggs, McClowry, & Snow, Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Briggs, McClowry and Snow2008). Overly harsh behaviors create an environment of inconsistency and unpredictability that results in pronounced child behavioral problems and concomitant changes in biological stress responses (Bugental & Grusec, Reference Bugental, Grusec, Lerner and Damon2006; Loman & Gunnar, Reference Loman and Gunnar2010). Parenting behaviors during childhood are thought to be particularly important for youth socioemotional development (Ainsworth, Reference Ainsworth1979; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982; Landry, Smith, Swank, & Guttentag, Reference Landry, Smith, Swank and Guttentag2008; Maccoby & Martin, Reference Maccoby, Martin, Mussen and Hetherington1983; Patterson, Reference Patterson1982; Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993). For example, hostile and rejecting parenting behaviors during toddlerhood, when children become increasingly mobile and autonomous, facilitate coercive family processes that translate into later youth conduct problems (Patterson, Reference Patterson1982; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, Reference Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby and Nagin2003; Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993). Although harsh parenting behaviors and parent–child conflict tend to be elevated during toddlerhood and decrease thereafter (Collins, Madsen, & Susman-Stillman, Reference Collins, Madsen and Susman-Stillman2005; Dallaire & Weinraub, Reference Dallaire and Weinraub2005; Trentacosta et al., Reference Trentacosta, Criss, Shaw, Lacourse, Hyde and Dishion2011), most developmental work on parenting has examined parenting within shorter developmental periods, such as infancy (Dallaire & Weinraub, Reference Dallaire and Weinraub2005) or adolescence (Forehand & Jones, Reference Forehand and Jones2002). Given the substantial individual (e.g., development of self-regulation) and social (e.g., entering school, forming peer relationships) changes that occur as youth move from early to late childhood (Blair & Diamond, Reference Blair and Diamond2008; Morrison, Ponitz, & McClelland, Reference Morrison, Ponitz, McClelland, Calkins and Bell2010), more research is needed to describe how harsh parenting behaviors change across childhood.

Neural structures within the corticolimbic system

Neural structures within the corticolimbic system, including the amygdala and medial regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC/mPFC), have been the focus of much of the research linking childhood adversity to brain development (Callaghan & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan and Tottenham2016; Gee, Reference Gee2016; McLaughlin, Sheridan, & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014). Given its critical role in emotion processing, salience detection, and fear learning (LeDoux, Reference LeDoux2000), the amygdala forms the “hub” of the corticolimbic system (Benes, Reference Benes, Coch, Dawson and Fischer2010; Hariri, Reference Hariri2015). Neurons within the amygdala integrate information about the external environment from sensory cortices with contextual information from the hippocampus, sending efferent projections to other subcortical (e.g., hypothalamus) and cortical (e.g., PFC) regions to stimulate behavioral responses (e.g., activation of physiological stress responses, attention allocation) (LeDoux, Reference LeDoux2000; Whalen & Phelps, Reference Whalen and Phelps2009). Regions of the mPFC and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) support emotion regulation by integrating affective valuations from the amygdala with inputs from other neural regions (e.g., brainstem, thalamus) (Etkin, Egner, & Kalisch, Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011; Fuster, Reference Fuster2001; Ochsner, Silvers, & Buhle, Reference Ochsner, Silvers and Buhle2012; Quirk, Garcia, & González-Lima, Reference Quirk, Garcia and González-Lima2006). In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tasks that present emotional facial expressions, the mPFC (e.g., middle and medial frontal gyri), ACC, and amygdala are more active when participants view expressions of interpersonal distress (i.e., fear) and threat (i.e., anger) than neutral faces (Ekman & Friesen, Reference Ekman and Friesen1976; Fusar-Poli, Placentino, Carletti, Landi, & Abbamonte, Reference Fusar-Poli, Placentino, Carletti, Landi and Abbamonte2009; Oatley & Johnson-Laird, Reference Oatley and Johnson-Laird1987). Individual differences in amygdala, mPFC, and ACC reactivity to fearful and angry facial expressions have been associated with dysregulated cortisol signaling (Henckens et al., Reference Henckens, Klumpers, Everaerd, Kooijman, van Wingen and Fernández2016), internalizing (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011; Groenewold, Opmeer, de Jonge, Aleman, & Costafreda, Reference Groenewold, Opmeer, de Jonge, Aleman and Costafreda2013; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Loucks, Palmer, Brown, Solomon, Marchante and Whalen2011; Monk, Reference Monk2008), and externalizing behaviors (Coccaro, McCloskey, Fitzgerald, & Phan, Reference Coccaro, McCloskey, Fitzgerald and Phan2007; Hyde, Shaw, & Hariri, Reference Hyde, Shaw and Hariri2013; Marsh & Blair, Reference Marsh and Blair2008; Yang & Raine, Reference Yang and Raine2009) – all outcomes that have also been linked to adversity in childhood (Green et al., Reference Green, McLaughlin, Berglund, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2010; Loman & Gunnar, Reference Loman and Gunnar2010).

Dense structural (Bzdok, Laird, Zilles, Fox, & Eickhoff, Reference Bzdok, Laird, Zilles, Fox and Eickhoff2013; Goetschius et al., Reference Goetschius, Hein, Mattson, Lopez-Duran, Dotterer, Welsh and Monk2019) and functional (Motzkin, Philippi, Wolf, Baskaya, & Koenigs, Reference Motzkin, Philippi, Wolf, Baskaya and Koenigs2015; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Shehzad, Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Gotimer and Milham2009) connections between the amygdala, regions of the mPFC, and the ACC suggest that an examination of activation within these regions can be complemented by exploring their connectivity (Menon, Reference Menon2011). Indeed, amygdala–PFC connectivity has been associated with multiple forms of psychopathology that are marked by deficits in emotion processing, cross-sectionally (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Shaw and Hariri2013; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Loucks, Palmer, Brown, Solomon, Marchante and Whalen2011; Price & Drevets, Reference Price and Drevets2010) and longitudinally (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Swartz, Shaw, Forbes and Hyde2018; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gard, Shaw, Forbes, Neumann and Hyde2018).

Adversity effects on corticolimbic system function

A rich literature has linked greater childhood adversity with both greater (Gianaros et al., Reference Gianaros, Horenstein, Hariri, Sheu, Manuck, Matthews and Cohen2008; Jedd et al., Reference Jedd, Hunt, Cicchetti, Hunt, Cowell, Rogosch and Thomas2015; Maheu et al., Reference Maheu, Dozier, Guyer, Mandell, Peloso, Poeth and Ernst2010; McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, De Brito, Sebastian, Mechelli, Bird, Kelly and Viding2011; Pozzi et al., Reference Pozzi, Simmons, Bousman, Vijayakumar, Bray, Dandash and Whittle2019; Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Luby, Botteron, Dietrich, McAvoy and Barch2014; Tottenham et al., Reference Tottenham, Hare, Millner, Gilhooly, Zevin and Casey2011) and less (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017; Holz et al., Reference Holz, Boecker-Schlier, Buchmann, Blomeyer, Jennen-Steinmetz, Baumeister and Laucht2017; Javanbakht et al., Reference Javanbakht, King, Evans, Swain, Angstadt, Phan and Liberzon2015; Taylor, Eisenberger, Saxbe, Lehman, & Lieberman, Reference Taylor, Eisenberger, Saxbe, Lehman and Lieberman2006) amygdala reactivity to fearful and angry facial expressions. Emotional neglect and childhood trauma have also been associated with greater lateral PFC activation during emotion regulation (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Williams, Ho, King, Humphreys, Price and Gotlib2017; Marusak, Martin, Etkin, & Thomason, Reference Marusak, Martin, Etkin and Thomason2015), and less mPFC reactivity to angry and fearful facial expressions (van Harmelen et al., Reference van Harmelen, van Tol, Dalgleish, van der Wee, Veltman, Aleman and Elzinga2014). More research is needed to address these directional inconsistencies, which may emerge from different operationalizations of adversity and/or that some studies combine angry and fearful facial expressions into one “threat” condition or examine only one facial expression (i.e., angry or fear). For example, most of the research linking adversity to threat-related amygdala function (reviewed in Hein & Monk, Reference Hein and Monk2017) has focused on the neural effects of childhood maltreatment and reported positive associations (for examples of structural MRI studies that have examined normative parenting behaviors, see Whittle et al., Reference Whittle, Yap, Yücel, Fornito, Simmons, Barrett and Allen2008, Reference Whittle, Simmons, Dennison, Vijayakumar, Schwartz, Yap and Allen2014, Reference Whittle, Vijayakumar, Dennison, Schwartz, Simmons, Sheeber and Allen2016, Reference Whittle, Vijayakumar, Simmons, Dennison, Schwartz, Pantelis and Allen2017). Although far fewer task-based fMRI studies have examined more common forms of adversity (e.g., harsh parenting), those that have (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017; Holz et al., Reference Holz, Boecker-Schlier, Buchmann, Blomeyer, Jennen-Steinmetz, Baumeister and Laucht2017) reported negative associations with threat-related amygdala reactivity (although see Pozzi et al., Reference Pozzi, Simmons, Bousman, Vijayakumar, Bray, Dandash and Whittle2019). For examinations of prefrontal function, inconsistencies in previous work may also stem from region-of-interest approaches that do not account for functional heterogeneity within the PFC (e.g., dorsal vs. ventral regions).

Comparatively few studies have examined the effects of adversity on corticolimbic connectivity during socioemotional processing. However, as in studies of amygdala activation, the pattern of results appears to diverge depending on the operationalization of adversity. Childhood maltreatment and previous institutionalization have been associated with stronger amygdala–mPFC connectivity during fear processing (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Flannery, Goff, Humphreys, Telzer and Tottenham2013a), angry and fear processing as one “threat condition” (Jedd et al., Reference Jedd, Hunt, Cicchetti, Hunt, Cowell, Rogosch and Thomas2015), negative versus neutral images (Peverill, Sheridan, Busso, & McLaughlin, Reference Peverill, Sheridan, Busso and McLaughlin2019), and while viewing several emotional facial expressions versus shapes (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Ho, Humphreys, King, Foland-Ross, Colich and Gotlib2020; Pozzi et al., Reference Pozzi, Simmons, Bousman, Vijayakumar, Bray, Dandash and Whittle2019). In contrast, lower family income has been associated with weaker amygdala–PFC connectivity during emotion regulation (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Evans, Angstadt, Ho, Sripada, Swain and Phan2013), and during fearful face processing (Javanbakht et al., Reference Javanbakht, King, Evans, Swain, Angstadt, Phan and Liberzon2015). Thus, more research is needed to examine the associations between adversity and corticolimbic connectivity, with greater attention to common forms of childhood adversity (e.g., harsh parenting). Directional inconsistencies in the literature may also stem from reliance on relatively small samples recruited by convenience or based on narrow inclusion criteria (e.g., maltreated samples). More research is needed using larger population-based samples with a clear sampling frame that include families with dimensional exposure to adversity.

Environmental effects on corticolimbic function: Consideration of developmental timing

The developmental trajectories of the amygdala and the PFC suggest that there may be multiple windows of vulnerability during which these regions may be differentially sensitive to the effects of adversity. Structurally, the rate of volumetric growth in the amygdala is largest during the early postnatal years (Payne, Machado, Bliwise, & Bachevalier, Reference Payne, Machado, Bliwise and Bachevalier2010), increasing in volume by more than 100% during the first year of life (Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Shi, Woolson, Knickmeyer, Short, Lin and Shen2012). The PFC, however, continues to develop throughout childhood into adolescence and adulthood (Gogtay et al., Reference Gogtay, Giedd, Lusk, Hayashi, Greenstein, Vaituzis and Thompson2004; Sowell et al., Reference Sowell, Peterson, Thompson, Welcome, Henkenius and Toga2003). Prefrontal gray matter density has been shown to peak during the prepubertal stage (i.e., 10–12 years), followed by synaptic pruning and dendritic arborization (Andersen & Teicher, Reference Andersen and Teicher2008; Casey, Jones, & Hare, Reference Casey, Jones and Hare2008; Lenroot & Giedd, Reference Lenroot and Giedd2006). Functionally, children exhibit greater amygdala reactivity to emotional facial expressions than adolescents and adults (Monk, Reference Monk2008), and this trajectory is thought to underlie normative childhood fears (e.g., separation anxiety) that peak during childhood (Gee, Reference Gee2016). During adolescence, as projections from prefrontal regions to other brain regions become more well defined (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Jones and Hare2008; Swartz, Carrasco, Wiggins, Thomason, & Monk, Reference Swartz, Carrasco, Wiggins, Thomason and Monk2014), mPFC activation to emotional facial expressions increases (Blakemore, Reference Blakemore2008). In a seminal paper by Gee et al. (Reference Gee, Humphreys, Flannery, Goff, Telzer, Shapiro and Tottenham2013b), amygdala–mPFC connectivity during fear processing was shown to shift from positive during childhood to negative during adolescence. In this analysis, positive amygdala–mPFC connectivity reflected positively correlated amygdala and mPFC activation while children were looking at fearful facial stimuli; in adolescents and adults, the association between activity in these two regions became negative, thought to reflect less amygdala and greater mPFC activation (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Humphreys, Flannery, Goff, Telzer, Shapiro and Tottenham2013b; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kujawa, Lu, Fitzgerald, Klumpp, Fitzgerald and Phan2016).

Although several recent reviews highlight the importance of developmental timing for adversity effects on corticolimbic function (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015), few studies have tested this hypothesis in humans (for reviews of the nonhuman animal literature, see Callaghan & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan and Tottenham2016; Debiec & Sullivan, Reference Debiec and Sullivan2017). Using structural MRI, Pechtel, Lyons-Ruth, Anderson, and Teicher (Reference Pechtel, Lyons-Ruth, Anderson and Teicher2014) found that the severity of exposure to maltreatment at ages 10–11 was most strongly associated with amygdala volume. Similarly, Andersen et al. (Reference Andersen, Tomada, Vincow, Valente, Polcari and Teicher2008) found that sexual abuse in early childhood was more strongly associated with subcortical volumes, whereas sexual abuse that occurred in late adolescence was more strongly associated with prefrontal volume. Beyond these structural studies, there is little work examining developmental timing using task-based fMRI. In one exception, using prospectively collected repeated measures of adversity across childhood, one study found that harsh parenting at age 2 was associated with less amygdala reactivity to fearful facial expressions at age 20, even after accounting for harsh parenting at age 12 (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017); however, this paper did not examine PFC function or amygdala–PFC connectivity. Moreover, by measuring parenting behaviors at isolated time points, this strategy assumes that parenting can be parsed into discrete moments in time rather than the notion that parenting behaviors are a product of continuous reciprocal interactions within the changing context (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009). It may be that an examination of initial levels (i.e., harsh parenting in early childhood) versus changes thereafter (i.e., the trajectory of harsh parenting across childhood) will reveal more complex effects of adversity on corticolimbic function during socioemotional processing. This explicit focus on evaluating the timing of harsh parenting effects on corticolimbic function builds on previous work in this sample that has examined the cumulative (i.e., across childhood) effects of threat- and deprivation-related experiences of adversity on amygdala–prefrontal white matter connectivity (Goetschius, Hein, Mitchell et al., Reference Goetschius, Hein, Mitchell, Lopez-Duran, McLoyd, Brooks-Gunn and Monk2020), amygdala reactivity during socioemotional processing (Hein et al., Reference Hein, Goetschius, McLoyd, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, Mitchell, Lopez-Duran, Hyde and Monk2020), and network-level resting-state functional connectivity (Goetschius, Hein, McLanahan et al., Reference Goetschius, Hein, McLanahan, Brooks-Gunn, McLoyd, Dotterer and Beltz2020)

The present study

The current study sought to advance our understanding of how trajectories of maternal harshness across childhood impact corticolimbic function in adolescence. First, in a large, national representative sample of children born in large US cities in 1998–2000 with an oversample for nonmarital births (i.e., the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study), we examined how parental harshness changed across childhood (i.e., from ages 3 to 9 years old) using linear growth curve modeling. Second, we evaluated the effects of harsh parenting in early childhood versus changes in harsh parenting across childhood on corticolimbic function during adolescence. There were two components to our hypotheses: (a) predictions about the timing of harsh parenting effects on subcortical versus cortical regions, and (b) predictions about the direction of effects. Consistent with animal models (Callaghan & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan and Tottenham2016; Debiec & Sullivan, Reference Debiec and Sullivan2017) and limited structural and functional longitudinal studies in human populations (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Tomada, Vincow, Valente, Polcari and Teicher2008; Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017; Pechtel et al., Reference Pechtel, Lyons-Ruth, Anderson and Teicher2014), we hypothesized that harsh parenting in early childhood would be associated with amygdala function, whereas changes in harsh parenting across childhood would be associated with prefrontal function (particularly in within medial regions). Additionally, as amygdala–PFC connectivity is a function of activation in both regions, we hypothesized that both initial levels and changes in harsh parenting across childhood would be associated with corticolimbic connectivity. As the previous literature varies widely with respect to the direction of effects (e.g., due to operationalization of adversity, definition of PFC target regions), however, our directional hypotheses were more exploratory in nature. That is, we hypothesized that harsh parenting in early childhood would be related to either greater (Hein & Monk, Reference Hein and Monk2017) or less (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017; Holz et al., Reference Holz, Boecker-Schlier, Buchmann, Blomeyer, Jennen-Steinmetz, Baumeister and Laucht2017) threat-related amygdala reactivity, increases in harsh parenting across childhood would be related to either greater (Colich et al., Reference Colich, Williams, Ho, King, Humphreys, Price and Gotlib2017) or less (van Harmelen et al., Reference van Harmelen, van Tol, Dalgleish, van der Wee, Veltman, Aleman and Elzinga2014) threat-related PFC reactivity, and harsh parenting during early childhood and increases in harsh parenting across childhood would be associated with either weaker (Javanbakht et al., Reference Javanbakht, King, Evans, Swain, Angstadt, Phan and Liberzon2015) or stronger (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Flannery, Goff, Humphreys, Telzer and Tottenham2013a) amygdala–mPFC connectivity during threat processing.

Methods

Sample

Participants were part of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), a longitudinal cohort of 4,898 children (52.4% boys) children born in large US cities between 1998 and 2000. The FFCWS oversampled for nonmarital births (~3:1), which resulted in substantial sociodemographic diversity in the sample (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, Reference Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel and McLanahan2001). At childbirth, mothers identified as Black non-Hispanic (N = 2,326, 47.5%), White non-Hispanic (N = 1,030, 21.1%), Hispanic (N = 1,336, 27.3%), or other (N = 194, 4.0%). Nearly 40% of the mothers reported less than a high school education at the birth interview, 25.3% with a high school degree or equivalent, 24.3% some college or technical training, and 10.7% who earned a college degree or higher. Parents in the FFCWS were interviewed at the hospital shortly after the birth of the target child, and again (by phone or in-person) at ages 1, 3, 5, 9, and 15 years old. Retention of the baseline sample was generally high at each of the assessment periods (77% to 90% for mother or primary caregiver interviews, 62% to 72% for home visits) (for detailed information about cohort retention across waves, see https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu).

At age 15, families from the Detroit, Toledo, and Chicago subsamples were asked to participate in the Study of Adolescent Neurodevelopment (SAND), a follow-up study to investigate the role of the environment on youth brain and behavioral development. Two-hundred and thirty-seven adolescents aged 15 to 17 (52.3% female) and their primary caregiver agreed to participate. Of the 237 families, teens self-identified as Black non-Hispanic (N = 179, 75.5%), Black Hispanic (N = 2, 0.8%), White non-Hispanic (N = 30, 12.7%), of Hispanic or Latino origin (N = 10, 4.2%), biracial (N = 13, 5.5%), or other non-Hispanic (N = 3, 1.3%). Primary caregivers were biological mothers (N = 216, 91.1%), biological fathers (N = 11, 4.6%), adoptive parents (N = 4, 1.7%), or other family members (N = 6, 2.5%). Median annual family income was between $25,000 to $29,999, with some primary caregivers reporting annual incomes below $4,999 (13%) and others reporting annual incomes above $90,000 (10.2%). Thus, the SAND sample is socioeconomically diverse, though primarily low-income, and comprising mostly Black American children and their biological mothers.

Procedure

The current paper uses data from both the core FFCWS and the SAND. We used measures of maternal harsh parenting from the FFCWS telephone and in-person interviews at ages 3, 5, and 9 years old. As the primary aim of this paper was to investigate whether initial levels and/or changes in parenting behaviors across childhood impacted youth corticolimbic function in adolescence, we limited our sample to families where the biological mother was the primary caregiver at the 3-, 5-, and 9-year assessments (i.e., to prevent artifacts introduced by changing informants across time); 216 out of 4,898 families were excluded. Detailed descriptions of the study protocols for each of the core FFCWS assessment periods can be found on the study website (https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu).

SAND subsample

At age 15, primary caregivers and adolescents in the SAND study participated in a one-day protocol that included collection of self-report, interviewer, observational, and biological data. Parents provided written consent and adolescents provided verbal assent for their participation in the SAND protocol. Families were reimbursed for their participation. All assessments and measures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan (IRB protocol # HUM00074392).

Measures

Maternal harshness

Maternal harshness was measured as physical discipline using a sum of five mother-reported items from the physical aggression subscale of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, Reference Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore and Runyan1998) at the 3-year (mean[SD] = 1.23[1.01], n = 3,284), 5-year (mean[SD] = 1.10[.97], n = 2,935), and 9-year (mean[SD] = .73 [.85], n = 3,083) assessments. Mothers were asked to rate how many times in the past year each disciplinary practice was used (“pinched him/her,” “slapped him/her on the hand, arm, or leg,” “spanked him/her on the bottom with your bare hand,” “hit child on the bottom with some hard object”), from 0 (never happened) to 6 (more than 20 items). The reliability of the harsh parenting items was low, though potentially adequate given the small pool of items (age 3: α = .61; age 5: α = .60; age 9: α = .70). This measure of harsh parenting has been used extensively in other publications from the FFCWS (e.g., Kim, Lee, Taylor, & Guterman, Reference Kim, Lee, Taylor and Guterman2014; Lee, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, Notterman, & Garfinkel, Reference Lee, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, Notterman and Garfinkel2013). Although we initially intended to include the psychological aggressions subscale of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale, the scale reliabilities were even lower than the physical aggressions subscale (e.g., at age 3: α = .55 for psychological aggressions). Thus, we focused our analyses on physical discipline components of harsh parenting.

In sensitivity analyses, we evaluated whether our models were robust to inclusion of harsh parenting at age 15 (i.e., the time of neuroimaging assessment), which was measured by a mean of three parent-reported corporeal punishment items (mean[SD] = 1.89 [.63], n = 159, α = .59) from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Frick, Reference Frick1991). Harsh parenting at age 15, as measured by the physical aggression subscales of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., Reference Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore and Runyan1998), could not be included as a time point in the linear growth curve models because only one item was collected in the age 15 wave of the FFCWS protocol.

Covariates

Several covariates were included in the analyses, each of which have been shown to impact corticolimbic function (Alarcón, Cservenka, Rudolph, Fair, & Nagel, Reference Alarcón, Cservenka, Rudolph, Fair and Nagel2015; Kubota, Banaji, & Phelps, Reference Kubota, Banaji and Phelps2012; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Pfeifer, Masten, Mazziotta, Iacoboni and Dapretto2012): (a) youth self-reported race and ethnicity at age 15, (b) youth gender (girl = 1), and (c) youth self-reported pubertal development. Race/ethnicity was coded as one dummy code for the largest group in the SAND sample (non-Hispanic Black [75.5%] = 1). Pubertal development was measured at age 15 using youth report on the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988), which includes two gender-specific items (e.g., for boys: voice changes; for girls: breast development), and three items for both genders (i.e., changes in height, skin, pubic hair). All items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = process has not started, 4 = seems completed), except for the menarche question for girls, which was dichotomous (1 = not started, 4 = started). Total pubertal development score was calculated as a mean of the five items for each gender (girls: mean [SD] = 3.58 [.46]; boys: mean [SD] = 2.86 [.50]).

Neuroimaging data

fMRI task

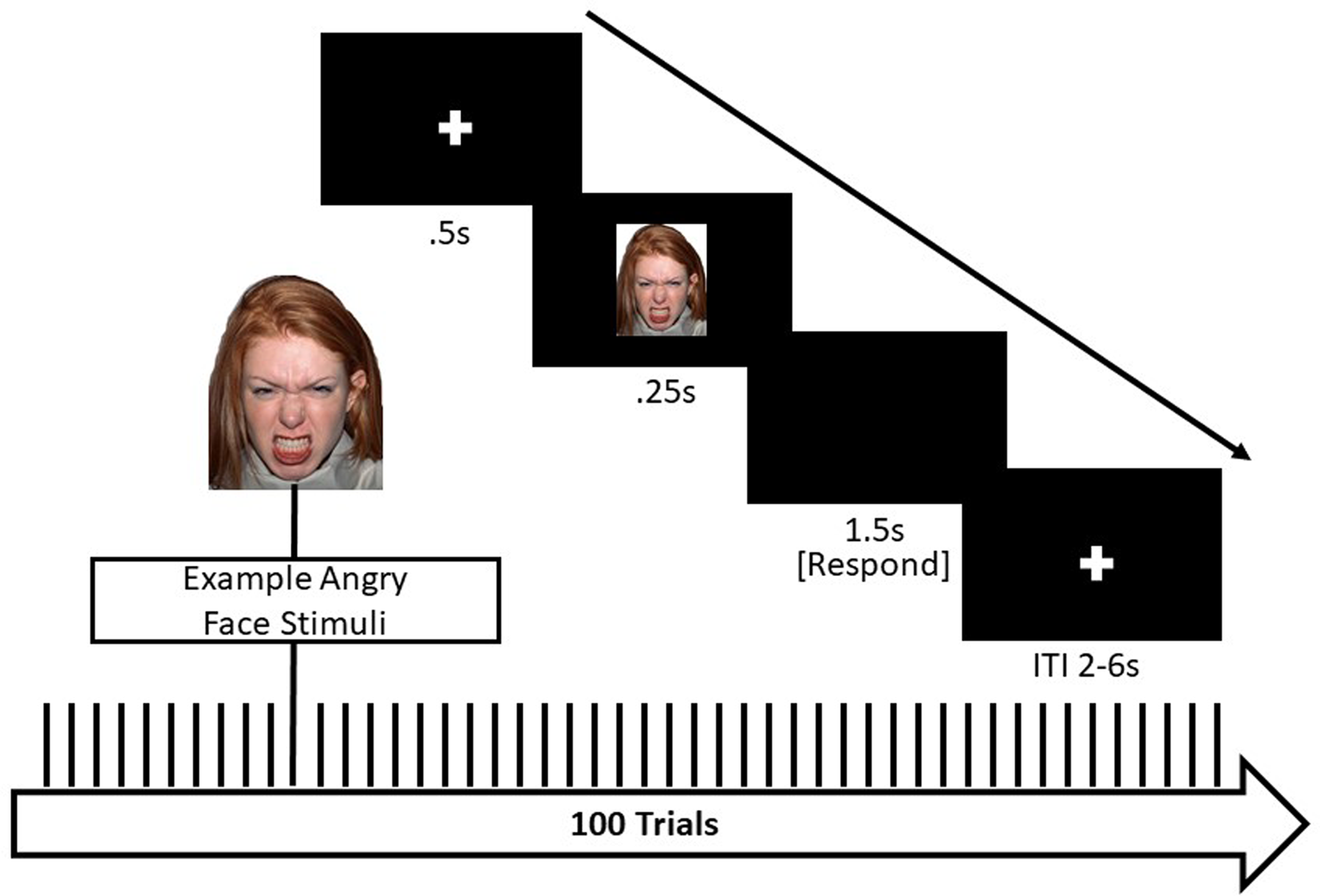

Participants completed an implicit emotion face processing task during continuous fMRI acquisition (see Figure 1). In this task, participants were asked to identify the gender of the actor by pressing their thumb for male or index finger for female (Hein et al., Reference Hein, Mattson, Dotterer, Mitchell, Lopez-Duran, Thomason and Monk2018). Faces from the NimStim set (Tottenham et al., Reference Tottenham, Tanaka, Leon, McCarry, Nurse, Hare and Nelson2009) were counterbalanced for gender and race (European American and African American). There were 100 pseudo-randomized trials, 20 trials each of the following emotions: fearful, happy, sad, neutral, and angry. Each trial consisted of a 500 ms fixation cross followed by a face presented for 250 ms. A black screen then appeared for 1,500 ms, during which participants responded to the stimulus presentation, followed by a jittered inter-trial interval (2,000, 4,000, or 6,000 ms). Total task time was 8.75 min. Accuracy and response times were collected using a nonmetallic fiber optic transducer linked to a response box.

Figure 1. Implicit emotional faces matching paradigm Note. This event-related task design included 100 trials, 20 each of the following facial expressions: angry, fearful, sad, neutral, and happy. Total task time was 8.75 min.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

MRI images were acquired using a GE Discovery MR750 3T scanner with an eight-channel head coil located at the UM Functional MRI Laboratory. High-resolution T1-weighted gradient echo (SPGR) images were collected (repetition time [TR] = 12 ms, echo time [TE] = 5 ms, interval time [TI] = 500 ms, flip angle = 15°, field of view (FOV) = 26 cm; slice thickness = 1.4 mm; 256 × 192 matrix; 110 slices) and used for preprocessing. Functional T2*-weighted BOLD images (TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 22 cm; slice thickness = 3 mm; 64 × 64 matrix; 40 axial slices) were acquired using a reverse spiral sequence, which has been shown to improve signal recovery in frontal regions (Glover & Law, Reference Glover and Law2001). Slices were prescribed parallel to the AC–PC line (same locations as structural scans). Slices were acquired contiguously, which optimized the effectiveness of the movement postprocessing algorithms. Images were reconstructed offline using processing steps to remove distortions caused by magnetic field inhomogeneity and other sources of misalignment to the structural data, which yields excellent coverage of subcortical areas of interest.

Anatomical images were homogeneity-corrected using SPM, then skull-stripped using the Brain Extraction Tool in FSL (version 5.0.7) (Jenkinson, Beckmann, Behrens, Woolrich, & Smith, Reference Jenkinson, Beckmann, Behrens, Woolrich and Smith2012; Smith, Reference Smith2002). Functional data were preprocessed in the following steps: removal of large temporal spikes in k-space data (>2 std dev), field map correction and image reconstruction using custom code in MATLAB; and slice-timing correction using SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). To address head motion, functional images were realigned to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure (AC–PC) plane in the mean image. Using SPM12, anatomical images were co-registered to the functional images. Functional images were normalized to the MNI Image space using parameters from the T1 images segmented into gray and white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, bone, soft tissue, and air using a Tissue Probability Map created in SPM12. Images were then smoothed using an isotropic 8-mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel. Following preprocessing, the Artifact Detection Tools (ART) software package (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/artifact_detect) identified motion outliers (>2 mm movement or 3.5° rotation); outlier volumes were individually regressed out of the participant's individual model. Additionally, because of the relatively extensive signal loss typically observed in the amygdala, single-subject BOLD fMRI data were only included in subsequent analyses if there was a minimum of 70% signal coverage in the left and right amygdala, defined using the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas in the Wake Forest University (WFU) PickAtlas Tool, version 1.04 (Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft, & Burdette, Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003). As the current paper additionally examined corticolimbic function within the PFC, participants with less than 70% coverage in the prefrontal lobe (defined using the AAL atlas) were removed. Lastly, to ensure participants were engaged in the task, participants were excluded if accuracy on the task was less than 70%. Of the 237 participants in the SAND neuroimaging study, usable fMRI data were available for 167 (74%) participants (Table 1). Participants without usable fMRI data did not differ from participants with usable fMRI data with respect to concurrent family monthly income, earlier measures of parental harshness, or youth gender or race and ethnicity (all ps > .10).

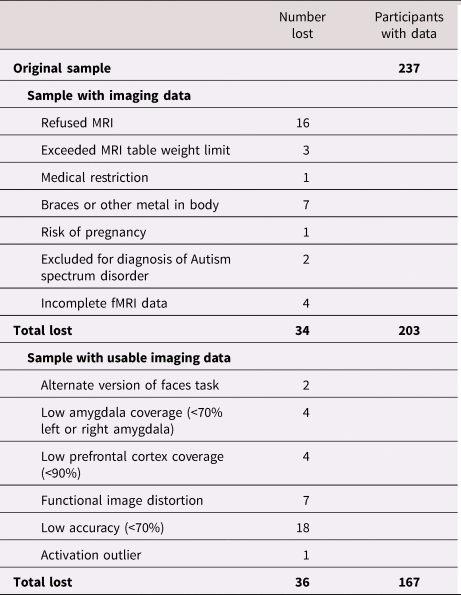

Table 1. Sources of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data loss

Note: Low amygdala coverage was defined using the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) definition of the bilateral amygdala from the WFU PickAtlas Tool (Maldjian et al., Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003). Low prefrontal cortex coverage was defined using a mask of the prefrontal lobe from the WFU PickAtlas Tool (Maldjian et al., Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003).

Activation analyses

The general linear model in SPM12 was used to estimate condition-specific BOLD activation for each individual and scan. Individual contrast images (i.e., weighted sum of the beta images) were then used in second-level random effects models to determine expression-specific reactivity using multiple regression. As the goal of this study was to examine corticolimbic reactivity during threat processing, we present results from the fearful facial expressions > neutral faces and angry facial expressions > neutral faces contrasts. We used two regions of interest (ROIs) to probe the effects of parenting of corticolimbic function: the amygdala and a large PFC mask. We defined the bilateral amygdala using the AAL atlas definition in the WFU PickAtlas Tool, version 1.04 (Maldjian et al., Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003). The PFC mask was defined by Brodmann's areas 9 (dorsolateral), 10 (dorsomedial), 11 and 47 (orbitofrontal), 24 and 32 (dorsal anterior cingulate), and 25 (subgenual cingulate), using the WFU PickAtlas Tool, version 1.04 (Maldjian et al., Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003). We used this broad PFC mask to: (a) compare our results to existing studies that used different definitions of the mPFC (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Telzer, Humphreys, Goff, Shapiro and Tottenham2014; van Harmelen et al., Reference van Harmelen, van Tol, Dalgleish, van der Wee, Veltman, Aleman and Elzinga2014) and to broaden the PFC regions examined, and because (b) the seven Brodmann's areas we identified have each been shown in nonhuman primate neural tract-tracer studies to be structurally connected to the amygdala (Amaral & Price, Reference Amaral and Price1984; Ghashghaei, Hilgetag, & Barbas, Reference Ghashghaei, Hilgetag and Barbas2007) and have been linked structurally to the amygdala in the current sample (Goetschius et al., Reference Goetschius, Hein, Mattson, Lopez-Duran, Dotterer, Welsh and Monk2019). We corrected for multiple comparisons using 3dClustSim (Cox, Chen, Glen, Reynolds, & Taylor, Reference Cox, Chen, Glen, Reynolds and Taylor2017; Forman et al., Reference Forman, Cohen, Fitzgerald, Eddy, Mintun and Noll1995) in AFNI version 16.1.14 (Cox, Reference Cox1996). Consistent with recommendations by Cox et al. (Reference Cox, Chen, Glen, Reynolds and Taylor2017), we implemented the spatial autocorrelation function (i.e., the –acf option) to model the spatial smoothness of noise volumes. Group-level smoothing values (x = 0.55, y = 6.41, z = 13.37) were estimated from a random 10% of participants’ individual-model residuals using the program 3dFWHMX, and then averaged across subjects. 3dClustSim uses a Monte Carlo simulation to provide a threshold that will achieve a family-wise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons of p < .05 within each ROI. We used a voxel-wise threshold of p < .001, which resulted in a threshold of 3 voxels for amygdala activation analyses and 29 voxels for PFC activation analyses. Our cluster thresholds were based on two-sided tests and used the nearest neighbor definition of “face and edge” (i.e., 3dClustSim command: NN = 2).

Functional connectivity analysis

Psychological×Physiological Interaction (PPI) analyses in the generalized PPI (gPPI) toolbox (McLaren, Ries, Xu, & Johnson, Reference McLaren, Ries, Xu and Johnson2012) in SPM12 were used to measure amygdala connectivity with regions of the PFC. In a PPI analysis, a design matrix is constructed at the level of the individual with the following columns of variables: (a) a physiological variable that represents the time course of the seed region (i.e., left or right amygdala) across the task, (b) a psychological variable indicating the experimental variable (e.g., onset times for fearful face stimuli), and (c) a product term of the interaction between the physiological and psychological variables. The gPPI toolbox developed by McLaren et al. (Reference McLaren, Ries, Xu and Johnson2012) allows for the simultaneous specification of all task conditions and interactions with the seed region time series in the same individual-level model (Friston et al., Reference Friston, Buechel, Fink, Morris, Rolls and Dolan1997). This is advantageous because it reduces the number of specified models and the overall Type I error rate.

As we were interested in examining changes in amygdala connectivity while participants viewed fearful and angry facial expressions versus neutral faces, we defined the left and right amygdala as seed regions using the AAL definition within the WFU PickAtlas Tool (Maldjian et al., Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003). Two general linear models at the individual level were constructed (i.e., one for each seed region). Using the gPPI toolbox, the time series of the left or right seed region was entered as the physiological variable in the design matrix, the explanatory variables for each of the five conditions in our task (i.e., facial expressions of fear, anger, happy, sad, and neutral faces) were entered as psychological variables, and the five product terms between the amygdala seed and conditions were entered as the interaction terms. We specified two primary contrasts at the individual level: fearful facial expressions interaction term > neutral faces interaction term, and angry facial expressions interaction term > neutral faces interaction term. Practically, this can be interpreted as a difference in slopes: is slope A (i.e., the interaction between amygdala reactivity and the fear/angry condition) greater or less than slope B (i.e., the interaction between amygdala reactivity and the neutral condition). Individual-level slopes (i.e., the betas corresponding to the interaction terms, e.g., fearful facial expressions × time series of amygdala activation) can then be extracted to determine the direction and strength of connectivity during the two conditions (e.g., fear, neutral). Contrasts from the individual level models were then used in random effects, group-level models to evaluate the impact of harsh parenting in early childhood and changes in harsh parenting across childhood on amygdala–PFC functional connectivity to fearful and angry facial expressions versus neutral faces. These models assess whether harsh parenting is associated with the difference in connectivity between conditions (or the difference in slopes). The contrasts of angry facial expressions > baseline, fearful facial expressions > baseline, and neutral faces > baseline were additionally used to confirm that our results were driven by connectivity during the emotion conditions (i.e., fear or anger) rather than the neutral face condition. Only ipsilateral connections between the amygdala and PFC were examined (e.g., left amygdala–left PFC), because neural tracer studies in nonhuman primates suggests that first-order amygdala connections are primarily ipsilateral (Ghashghaei et al., Reference Ghashghaei, Hilgetag and Barbas2007). Thus, we divided the same PFC mask from our activation analyses into left and right PFC masks for use as target regions in connectivity analyses. The same procedure using 3dClustSim (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Chen, Glen, Reynolds and Taylor2017; Forman et al., Reference Forman, Cohen, Fitzgerald, Eddy, Mintun and Noll1995) in AFNI version 16.1.14 (Cox, Reference Cox1996) as in the activation analyses was used to correct for multiple comparisons in the functional connectivity analyses. Group level average smoothing values for the left amygdala seed models (x = 0.55, y = 6.46, z = 13.48) and right amygdala seed models (x = 0.56, y = 6.44, z = 13.48) were used to estimate minimum cluster thresholds in the left and right PFC masks (k = 22) that would achieve a family-wise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons of p < .05 within each ROI, using a voxel-wise threshold of p < .001.

Analytic plan

First, linear growth curve modeling within Mplus version 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2006) was used to estimate the intercept and slope of maternal harshness. Though our neuroimaging sample was composed of 167 participants, we used all available cases from the core FFCWS (N = 4,682 families, where the mother was the primary caregiver at the 3-, 5-, and 9-year assessments) to estimate patterns of harsh parenting across childhood. Thus, the estimates of initial levels and changes in parenting behaviors across childhood are derived from a larger nationwide sample with greater power for estimation of these complex models. Cases with at least one data point were used in each analysis with the full maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator with robust standard errors, resulting in a sample size of N = 4,144 (N = 162 with valid neuroimaging data in the SAND). FIML estimation uses the covariance matrix of all available data to produce unbiased estimates and standard errors in the context of missing data (Enders & Bandalos, Reference Enders and Bandalos2001; McCartney, Burchinal, & Bub, Reference McCartney, Burchinal and Bub2006). Model fit was considered adequate if the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06 and the comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

To evaluate the effects of harsh parenting in early childhood and changes in harsh parenting behaviors across childhood on corticolimbic function, estimates of the intercept and slope of maternal harshness were extracted from Mplus for use in second-level random effects models within SPM12. First, the intercept or slope of maternal harshness was entered as the primary predictor in a linear regression model, with pubertal status, gender, and race and ethnicity as covariates. To evaluate the unique effects of the intercept/slope, a second set of models was estimated that additionally controlled for the slope/intercept of maternal harshness.

Results

Estimation of harsh parenting across childhood

The linear growth curve model of harsh parenting at ages 3, 5, and 9 in the FFCWS (N = 4,144; Figure 2) demonstrated good model fit (X2[1] = 5.62, p = .02; RMSEA = .03, 90% confidence interval [CI] [.01, .06]; CFI = 1.00, Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = .99) and indicated that, on average, initial levels (i.e., the intercept) of harsh parenting were positive and significantly different from zero (estimated intercept mean [SD] = 1.23[.02], p < .001). On average, levels of harsh parenting decreased from ages 3 to 9 (estimated slope mean [SD] = −.09[.003], p < .001). Although our primary goal was to examine individual variability from the mean trajectory of the overall group, we tested whether there was heterogeneity in growth trajectories using growth mixture modeling (Nagin & Odgers, Reference Nagin and Odgers2010). A three-group solution fit the data better than a two-group solution, based on fit indices and classification quality (Akaike information criterion [AIC] = 22,964.49, Bayesian information criteria [BIC] = 22,999.16, entropy = .79; posterior probabilities ranged from .84 to .93; Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test = 544.74, p < .001). The solution included “low-decreasing” (n = 2,041 [73%]; intercept B[SE] = .92[.03], slope B[SE] = −.11[.01]), “moderate-decreasing” (n = 950 [23%]; intercept B[SE] = 1.92[.07], slope B[SE] = −.07[.01]), and “high-increasing” (intercept B[SE] = 2.37[.17], slope B[SE] = .12[.03]) groups. However, the “high-increasing” group was quite small (n = 153 [4%]) and even smaller in the neuroimaging subsample (n = 13). Thus, we focused our analyses on examining individual variability from the group mean in a single group growth curve.

Figure 2. Individual observed values of harsh parenting across childhood. Note. N = 4,144. Spaghetti plot of individual observed values of harsh parenting at ages 3, 5, and 9 years. Group average trajectory depicted in bolded orange. Model fit: X2 (1) = 5.62, p = .02; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .03, 90% CI (.01, .06); comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.00, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .99, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .01. Loadings for the latent slope factor were specified as 0 (age 3), 2 (age 5), and 6 (age 9), and all loadings for the latent intercept factor were set equal to 1.

To inform future research, we examined whether youth in the three trajectory groups differed on non-neural characteristics. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) revealed significant group differences in pubertal development (F (2,161) = 4.31, p < .05) and parent-reported corporal punishment at age 15 (F (2,158) = 20.83, p < .001), but not household income at age 15. Post hoc Tukey tests showed that youth in the high-increasing group (N = 13) were less pubertally-advanced and exposed to more corporal punishment at age 15 than youth in the low-decreasing (N = 93) and moderate-decreasing (N = 56) groups. Chi-square difference tests revealed no group differences in youth gender, youth race/ethnicity, and parent education or marital status (all ps > .10).

Harsh parenting effects on corticolimbic activation

We next used the estimated intercept and slope terms for each participant to evaluate whether harsh parenting in early childhood (i.e., the intercept, set at age 3) was most strongly associated with amygdala function and whether changes in harsh parenting across childhood (i.e., the slope) were most predictive of PFC function during emotional face processing at age 15. Across all models, the associations between harsh parenting and corticolimbic activation were specific to angry (i.e., anger vs. neutral contrast), rather than fearful facial expressions (i.e., fear vs. neutral contrast). First, greater harsh parenting in early childhood was associated with less left amygdala (but not PFC) reactivity to angry facial expressions versus neutral faces (see Table 2 and Figure 3), controlling for changes in harsh parenting across childhood (i.e., the slope term) and harsh parenting at age 15 (i.e., the same age as the neuroimaging data collection). In contrast, increases in harsh parenting from ages 3 to 9, controlling for harsh parenting in early childhood (i.e., the intercept) and harsh parenting at age 15, were associated with less right dorsal ACC (dACC) but not amygdala, reactivity to angry facial expressions versus neutral faces (Table 2 and Figure 3).

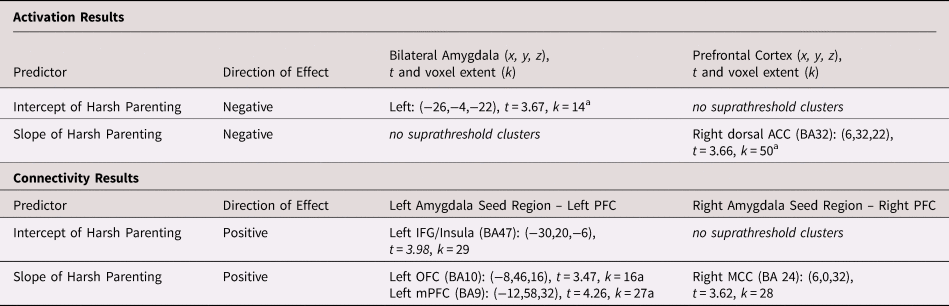

Table 2. Harsh parenting in early childhood and changes in harsh parenting across childhood predict corticolimbic activation and connectivity during angry face processing

Note: N = 162. All models controlled for youth gender, race, pubertal status, and the intercept/slope term. For activation, the results of the intercept and slope models of harsh parenting on corticolimbic reactivity were driven by less activation to angry facial expressions versus baseline (intercept model: p voxel < .05, [−24,−2,−22], t = 2.29, k = 59; slope model: p voxel < .05, [14,34,22], t = 3.21, k = 126), rather than greater activation to neutral facial expressions versus baseline (no clusters at p voxel < .05). For connectivity, the results of the intercept and slope models of harsh parenting on corticolimbic connectivity were driven by greater amygdala–PFC connectivity during angry face versus baseline processing (left amygdala seed slope model: p voxel < .05, [−8,46,16], t = 2.68, k = 232; left amygdala intercept model: p voxel < .01, [−2,53,4], t = 3.13, k = 85), rather than less amygdala–PFC connectivity during neutral face processing versus baseline (no clusters at p voxel < .05). Note that zero-order correlations between the intercept and slope of harsh parenting and harsh parenting at age 15 ranged from .25 < | r | < .29.

ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; IFG = inferior frontal gyrus ; MCC = middle cingulate cortex; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; PFC = prefontal cortex

a Significant after accounting for harsh parenting at age 15 (concurrent to the neuroimaging assessment).

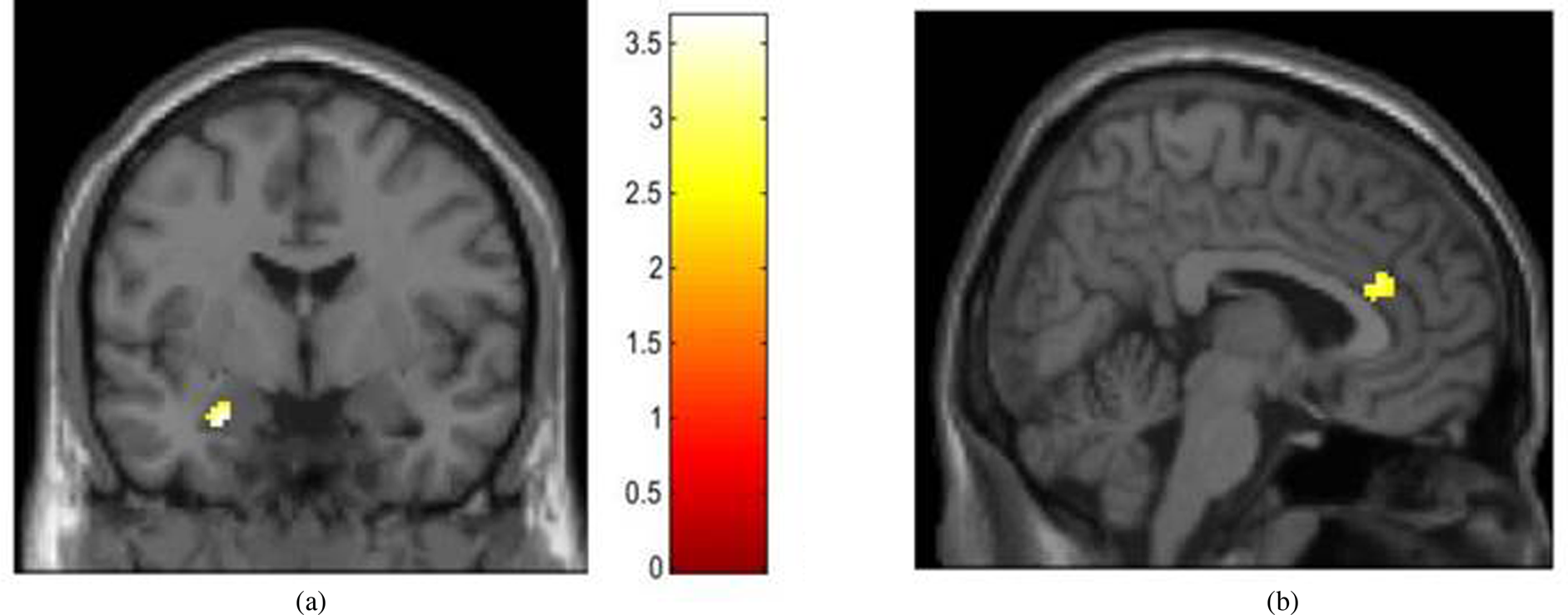

Figure 3. Harsh parenting in early childhood and increases in harsh parenting across childhood are associated with less corticolimbic activation during angry face processing. Note. N = 159. Results are from the most stringent models that control for youth gender, race, pubertal status, the intercept/slope term, and harsh parenting at age 15. (a) Greater harsh parenting in early childhood (i.e., the intercept from a linear growth curve model, set at age 3) associated with less left amygdala reactivity to angry versus neutral faces; (x, y, z) = (−26,−4,−22), t = 3.91, k = 16. (b). Increases in harsh parenting from ages 3 to 9 associated with less right dorsal anterior cingulate reactivity to angry versus neutral faces; (x, y, z) = (6,32,22), t = 3.66, k = 50.

Harsh parenting effects on corticolimbic connectivity

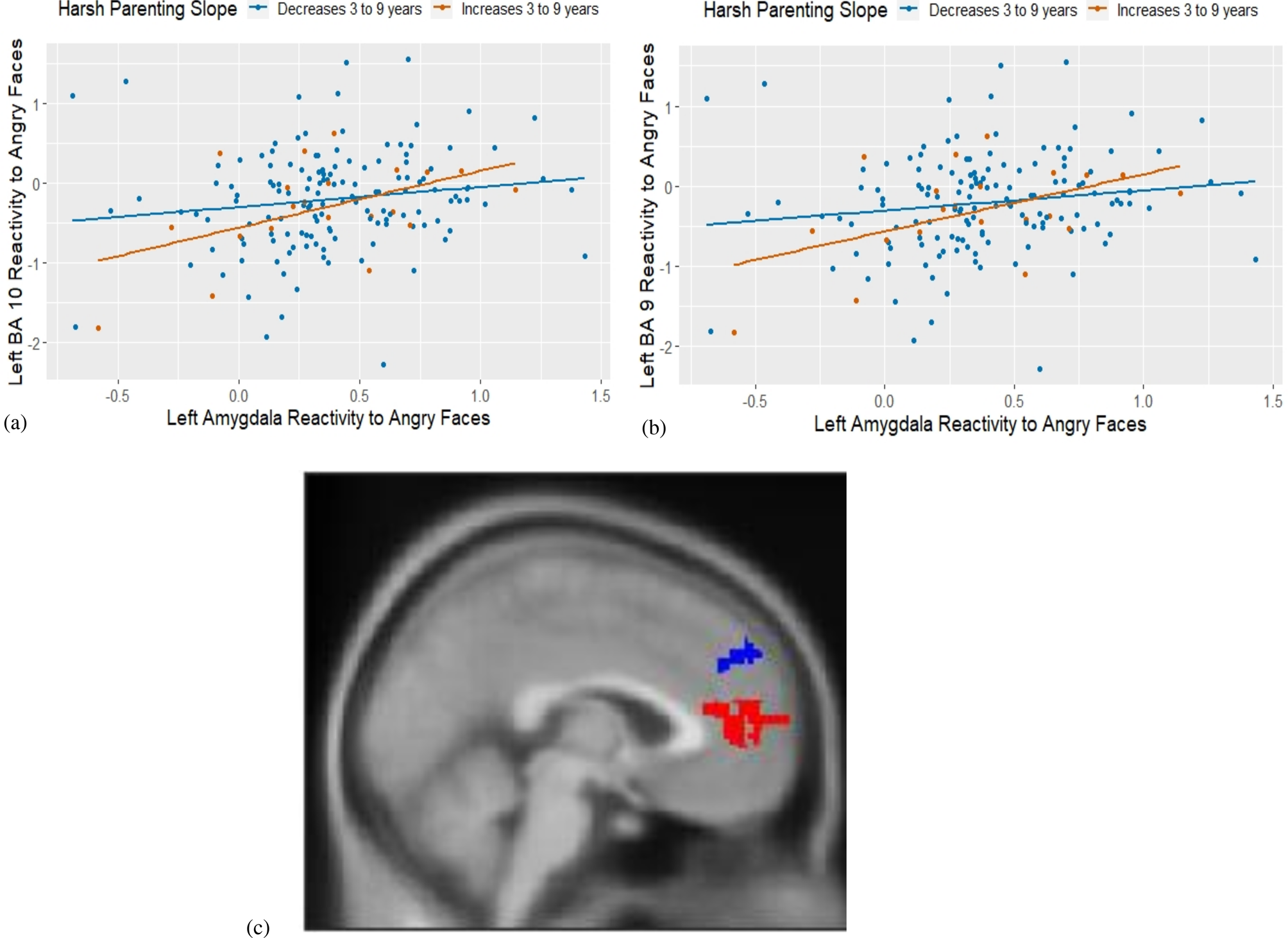

Consistent with the corticolimbic activation results, all models linking harsh parenting to amygdala–PFC connectivity during emotional face processing were specific to the angry versus neutral face contrast. In line with our hypotheses, both greater harsh parenting in early childhood and increases in harsh parenting from ages 3 to 9 years were uniquely (i.e., accounting for their overlap) associated with greater amygdala–PFC connectivity during angry face processing than neutral face processing (Table 2). After accounting for harsh parenting at age 15, however, only changes in harsh parenting across childhood (i.e., the slope term) were associated with amygdala–PFC connectivity during angry face processing. To determine the direction of amygdala–PFC connectivity (i.e., whether activation in the seed and target region was positively or negatively coupled), we extracted the connectivity estimates during each condition separately. As shown in Figure 4, increases in harsh parenting across childhood were associated with more positive left amygdala–left orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and left amygdala–left mPFC connectivity during angry face processing but not neutral face processing (Table 2 and Figure 4).

Figure 4. Increases in harsh parenting across childhood are associated with more positive left amygdala–left prefrontal cortex connectivity during angry face processing. Note. N = 159. BA = Brodmann's area. Results are from the most stringent models that control for youth gender, race, pubertal status, the intercept/slope term, and harsh parenting at age 15. (a) Increases in harsh parenting from ages three to nine (i.e., the slope) associated with more positive left amygdala–left orbitofrontal (BA10) connectivity during angry face processing in adolescence; (x, y, z) = (−8,46,16), t = 3.75, k = 40; (b) Increases in harsh parenting from ages three to nine (i.e., the slope) associated with more positive left amygdala–left medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (BA9) connectivity during angry face processing in adolescence; (x, y, z) = (−12,58,32), t = 4.26,k = 27; (c) Image of identified clusters in (a, in red) and (b, in blue).

Post-hoc exploratory analyses

Cumulative exposure to harsh parenting

Although our results suggest that the timing of exposure to harsh parenting is important for corticolimbic function in adolescence, our results could also reflect cumulative risk effects (Sameroff, Seifer, Barocas, Zax, & Greenspan, Reference Sameroff, Seifer, Barocas, Zax and Greenspan1987). That is, it may be that youth with the highest levels of harsh parenting in early childhood were also exposed to the highest levels of harsh parenting at subsequent ages and, thus, our results could be accounted for by a cumulative effect of harsh parenting across childhood. Using methods traditional to cumulative risk research (Evans, Li, & Whipple, Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013), we calculated the number of waves (i.e., 3-, 5-, and 9-year waves; possible cumulative risk score 0–3) during which an individual scored in the top quartile of harsh parenting. Of the 162 families with valid harsh parenting data at all three waves, most families (62.3%) were low risk across all three waves. Twenty-eight (17.3%) and 21 (13%) families were at-risk in one or two waves, respectively, and 12 (7.4%) families scored in the top quartile of harsh parenting at all three waves. Controlling for participant demographics at age 15, we examined whether cumulative risk scores were associated with (a) amygdala activation, (b) PFC activation, and (c) amygdala–PFC connectivity during angry versus neutral face processing at age 15 years. Consistent with the notion that timing of exposure to harsh parenting is important for corticolimbic development, the cumulative harsh parenting risk score was not associated with amygdala or PFC activation or connectivity (no clusters above threshold).

Gender differences

Based on previous research (Everaerd et al., Reference Everaerd, Klumpers, Zwiers, Guadalupe, Franke, van Oostrom and Tendolkar2016; Tottenham & Sheridan, Reference Tottenham and Sheridan2009; Whittle et al., Reference Whittle, Vijayakumar, Simmons, Dennison, Schwartz, Pantelis and Allen2017), we examined possible gender differences in the effects of harsh parenting on corticolimbic activation and connectivity during angry versus neutral face processing via exploratory analyses. First, we constructed interaction terms between the intercept/slope of harsh parenting and gender. Two linear regression models were used to estimate the effects of each interaction term on corticolimbic activation and connectivity, accounting for the main effects of the harsh parenting intercept and slope (both mean-centered), gender, pubertal development, and race/ethnicity. There were no statistically significant associations between the interaction terms and amygdala or prefrontal reactivity to angry versus neutral faces, or condition-specific amygdala–prefrontal connectivity. To stimulate future work in this area, we re-analyzed our data stratified by gender. Although there were no associations between harsh parenting and amygdala or prefrontal reactivity in boys (n = 75) or girls (n = 87; likely due to the reduced sample size/power), the effects of harsh parenting on left amygdala–left prefrontal connectivity were observed in girls only. Consistent with the pattern of findings in the total sample, increases in harsh parenting across childhood (accounting for initial levels of harsh parenting and parenting at age 15 years ) were associated with stronger positive left amygdala–left OFC ([x, y, z] = [−18, 56, 24], t = 4.94, k = 400) and left amygdala–left mPFC ([x, y, z] = [−22, 56, −8], t = 3.88, k = 23) connectivity during angry but not neutral face processing. Although these findings suggest that future work should explore gender differences in parenting effects on brain development, we caution readers that these results are likely underpowered and were exploratory in nature.

Discussion

The current study examined how harsh parenting behaviors change across childhood in a large, population-based sample of sociodemographically-diverse families, and explored how harsh parenting in early childhood and changes in harsh parenting across childhood were associated with subsequent corticolimbic function during adolescence. One of the study's strengths was the integration of data from an existing nationwide study of nearly 5,000 families followed prospectively from birth with neuroimaging data from a subsample recruited during adolescence. Consistent with prior research on trajectories of parenting behaviors during shorter developmental windows (Dallaire & Weinraub, Reference Dallaire and Weinraub2005; Kim, Pears, Fisher, Connelly, & Landsverk, Reference Kim, Pears, Fisher, Connelly and Landsverk2010), harsh parenting was initially high at age 3 and decreased thereafter through age 9 years. Moreover, consistent with animal models and theory (Debiec & Sullivan, Reference Debiec and Sullivan2017; Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015), we found that harsh parenting in early childhood was associated with less amygdala activation during socioemotional processing at age 15, whereas increases in harsh parenting from ages 3 to 9 years were associated with less activation in the dACC at age 15. In stringent models that accounted for harsh parenting age 15 (i.e., concurrent to the neuroimaging assessment), only increases in harsh parenting across childhood were associated with stronger positive amygdala–PFC connectivity during angry versus neutral face processing.

The trajectory of harsh parenting across childhood

In a population-based sample of families followed prospectively across childhood (Reichman et al., Reference Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel and McLanahan2001), maternal harshness changed from ages 3 to 9 in ways that mirror the developmental competencies of each developmental stage. On average, maternal harshness was greatest at age 3, when children are increasingly mobile and normatively evince greater emotionality (Shaw & Bell, Reference Shaw and Bell1993). Thereafter, from ages 3 to 9, maternal harshness decreased. During middle childhood (5 to 12 years), affective expression within the parent–child dyad has been shown to decrease, where both children and parents show less overt negative behaviors (e.g., coercion, emotional outbursts) (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Madsen and Susman-Stillman2005; Forehand & Jones, Reference Forehand and Jones2002; Shanahan, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, Reference Shanahan, McHale, Osgood and Crouter2007). Our results in the nationwide FFCWS build upon previous work that tracked changes in parenting behaviors during shorter developmental windows, such as during infancy and early childhood (Dallaire & Weinraub, Reference Dallaire and Weinraub2005; Lipscomb et al., Reference Lipscomb, Leve, Harold, Neiderhiser, Shaw, Ge and Reiss2011). Critically, reliance on a population-based sample of families over-sampled for sociodemographic risk suggests that these patterns of maternal harshness across childhood are reflective of the broader population of US families of living in urban and impoverished contexts, who are exposed to substantial environmental adversity (McLoyd, Reference McLoyd1998).

Developmental timing modulates adversity effects on corticolimbic function

Although several recent reviews have posited that exposure to harsh contexts impacts corticolimbic function in a timing-specific manner (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Tottenham, Reference Tottenham2015), our study is one of the first to empirically test this hypothesis in humans using repeated measures of harsh parenting across childhood in a population-based sample of low-income adolescents. We found that harsh parenting in early childhood was associated with less amygdala, but not PFC or ACC, activation, and that increases in harsh parenting thereafter were associated with less dACC, but not amygdala, activation during angry face processing. That we found no effects of cumulative exposure to harsh parenting across childhood on corticolimbic function reiterates the importance of timing of exposure for subsequent amygdala and prefrontal function. Much of the theoretical rationale for the notion of “sensitive periods” emerged from foundational work in humans documenting the developmental trajectories of subcortical and cortical brain development (Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Shi, Woolson, Knickmeyer, Short, Lin and Shen2012), and from animal studies wherein environmental exposure can be manipulated. For example, rhesus monkeys separated from their mother at 1-week versus 1-month of age or control animals (no separation), showed a significant decrease in gene expression in lateral and basal amygdala nuclei, more so than in prefrontal regions (Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Ebert, Lewis, Levitt, Cameron and Mirnics2007). In contrast to subcortical regions such as the amygdala, regions of the PFC develop into adulthood (Lenroot & Giedd, Reference Lenroot and Giedd2006; Sowell et al., Reference Sowell, Peterson, Thompson, Welcome, Henkenius and Toga2003). Structural MRI studies have shown that gray matter volume in the PFC increases during the preadolescent period, followed by postadolescent decrease (Giedd et al., Reference Giedd, Blumenthal, Jeffries, Castellanos, Liu, Zijdenbos and Rapoport1999); such volumetric changes correspond with increasing activation in the ACC and mPFC, and parallel behavioral improvements in executive functioning and emotion regulation (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Jones and Hare2008). Consistent with the notion that windows of vulnerability occur during developmental stages marked by rapid change (Andersen & Teicher, Reference Andersen and Teicher2008), it may be that prepubertal youth experience neural reorganization following environmental adversity. Our results are consistent with the existing structural MRI studies in this area that have reported similar timing-specific results for the effects of sexual abuse on subcortical and prefrontal volumes: abuse that occurred between ages 3 and 5 was associated with hippocampal, but not PFC volume, whereas abuse that occurred between ages 14 and 16 was associated with PFC volume, but not hippocampal volume (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Tomada, Vincow, Valente, Polcari and Teicher2008; Pechtel et al., Reference Pechtel, Lyons-Ruth, Anderson and Teicher2014). Our study extends this research to corticolimbic function and a measure of a more common form of childhood adversity – harsh parenting. In a recent paper (Gard, McLoyd, Mitchell, & Hyde, Reference Gard, McLoyd, Mitchell and Hyde2020), we replicated the timing effects presented here, using another unfortunately common experience faced by children in the United States: neighborhood disadvantage. However, the effects persisted above-and-beyond harsh parenting (see Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017, for a similar conclusion in a different sample), suggesting that both harsh parenting and living in a disadvantage neighborhood sculpt corticolimbic function in a timing-specific manner.

Inconsistencies in adversity – amygdala function associations

That harsh parenting in early childhood was associated with less threat-related amygdala reactivity was in the opposite direction to most, but not all, previous research. A meta-analysis found that individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment exhibited greater amygdala activation to threatening emotional facial expressions (Hein & Monk, Reference Hein and Monk2017). In contrast, three studies that operationalized childhood adversity as family income, family conflict, or harsh parenting reported that greater adversity was associated with less amygdala reactivity to threatening facial expressions (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017; Holz et al., Reference Holz, Boecker-Schlier, Buchmann, Blomeyer, Jennen-Steinmetz, Baumeister and Laucht2017; Javanbakht et al., Reference Javanbakht, King, Evans, Swain, Angstadt, Phan and Liberzon2015), consistent the results reported here. Moreover, a recent study found that individuals who were physically abused or neglected evinced greater threat-related amygdala reactivity, whereas individuals who experienced both types of maltreatment showed less threat-related amygdala reactivity compared to controls (Puetz, Viding, Gerin, & Pingault, Reference Puetz, Viding, Gerin and Pingault2019). Collectively, this research suggests that the severity, frequency, and type of adversity may modulate the effects on neural function, particularly with regards to the direction of associations with amygdala activation. A wealth of literature indicates that chronic exposure to early life adversity leads to hypoactivation of physiological stress responses (Loman & Gunnar, Reference Loman and Gunnar2010). Similarly, although amygdala sensitivity to environmental signals of threat or danger is adaptive in the short term, particularly for youth living in adverse contexts, persistent hyperactivation of physiological response systems (e.g., the hypothalamic–pituitary−adrenocortical [HPA] axis) can lead to a wide array of diseases (McEwen & McEwen, Reference McEwen and McEwen2017). Thus, tentatively, blunted amygdala reactivity to threatening facial expressions following exposure to chronic, daily adversities (e.g., low family income, harsh parenting) may be an adaptive response that facilitates allostasis and minimizes exposure to neurotoxic physiological hormones (e.g., cortisol).

Associations between harsh parenting and prefrontal function

We also found that increases in harsh parenting across childhood were associated with less mPFC reactivity (centered in the dACC) during socioemotional processing, consistent with a study by van Harmelen et al. (Reference van Harmelen, van Tol, Dalgleish, van der Wee, Veltman, Aleman and Elzinga2014). Dorsal regions of the PFC/ACC are thought to support the cognitive components of emotion processing, including appraisal during passive attendance to emotional facial expressions (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011). One interpretation of our results is that youth exposed to recurrent harsh parenting behaviors across childhood fail to recruit the dACC while viewing threatening facial expressions. Transcranial magnetic stimulation applied over the dACC (BAs 24 and 32) has been shown to impair discrimination of angry faces (Harmer, Thilo, Rothwell, & Goodwin, Reference Harmer, Thilo, Rothwell and Goodwin2001), lending support for the idea that failed recruitment of the dACC generates inappropriate responses to threatening stimuli. Indeed, multiple forms of psychopathology have been associated with less dACC reactivity during angry face processing, including antisocial behavior (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Shaw and Hariri2013; Yang & Raine, Reference Yang and Raine2009) and generalized anxiety disorder (Mochcovitch, da Rocha Freire, Garcia, & Nardi, Reference Mochcovitch, da Rocha Freire, Garcia and Nardi2014). Although our results suggest that the neural effects of harsh parenting were centered in the mPFC/dACC, several other studies have reported negative associations between childhood adversity and neural activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC)/inferior frontal gyrus (Fonzo et al., Reference Fonzo, Ramsawh, Flagan, Simmons, Sullivan, Allard and Stein2016; Liberzon et al., Reference Liberzon, Ma, Okada, Shaun Ho, Swain and Evans2015), highlighting potentially diffuse effects of adversity on PFC function. Identification of dorsal rather than ventral regions of the mPFC in the current study could reflect the fact that our emotional faces matching task captured cognitive (i.e., perceptual processing) rather than regulatory components of emotion processing (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011; Fuster, Reference Fuster2001).

Associations between harsh parenting and amygdala-prefrontal connectivity

We also found that increases in harsh parenting across childhood were associated with stronger positive, rather than weaker negative, amygdala–prefrontal connectivity (centered on Brodmann's areas 10 [OFC] and 9 [mPFC]) during angry compared to neutral face processing. Several studies using task-based or resting-state fMRI have found that children exhibit positive amygdala–mPFC connectivity during threat processing (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Humphreys, Flannery, Goff, Telzer, Shapiro and Tottenham2013b). Positive amygdala–mPFC connectivity has been associated with anxiety in children (Demenescu et al., Reference Demenescu, Kortekaas, Cremers, Renken, van Tol, van der Wee and Aleman2013; Gee et al., Reference Gee, Humphreys, Flannery, Goff, Telzer, Shapiro and Tottenham2013b) and internalizing and externalizing behaviors in adults (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Swartz, Shaw, Forbes and Hyde2018; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gard, Shaw, Forbes, Neumann and Hyde2018). Adolescents and adults, in contrast, evince stronger negative amygdala–mPFC connectivity (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Humphreys, Flannery, Goff, Telzer, Shapiro and Tottenham2013b). Previous research has shown that youth exposed to maltreatment or previous institutionalization show stronger negative amygdala–mPFC connectivity during threat processing, supporting a “stress-acceleration” hypothesis (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Gabard-Durnam, Flannery, Goff, Humphreys, Telzer and Tottenham2013a; Jedd et al., Reference Jedd, Hunt, Cicchetti, Hunt, Cowell, Rogosch and Thomas2015; Peverill et al., Reference Peverill, Sheridan, Busso and McLaughlin2019). However, our results suggest that the youth in our sample exposed to harsh parenting are not maturing earlier but, rather, show a potentially “immature” pattern of amygdala–prefrontal connectivity reflective of younger children.

Specificity of angry facial expressions

That the effects of harsh parenting on corticolimbic function were specific to the angry facial expressions versus neutral faces contrast suggests that more research is needed to determine the affective specificity of adversity effects on corticolimbic function. Maheu et al. (Reference Maheu, Dozier, Guyer, Mandell, Peloso, Poeth and Ernst2010) also found that the effects of childhood maltreatment on amygdala function were specific to angry facial expressions, whereas Gard et al. (Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017) and van Harmelen et al. Reference van Harmelen, van Tol, Dalgleish, van der Wee, Veltman, Aleman and Elzinga2014) did not report stronger effects for angry face processing. Previous reports indicate that physically abused children may process angry facial expressions differently than nonmaltreated controls (Pollak & Sinha, Reference Pollak and Sinha2002; Pollak & Tolley-Schell, Reference Pollak and Tolley-Schell2003). Compared to nonmaltreated children, physically abused children may require less perceptual information to correctly identify facial expressions of anger (Pollak & Sinha, Reference Pollak and Sinha2002), and respond more quickly to targets cued by angry faces versus happy faces (Pollak & Tolley-Schell, Reference Pollak and Tolley-Schell2003). More research is needed to determine whether certain features of adversity or the environmental context shape the associations with (and potential specificity for) different facial expressions. This is particularly important as several meta-analyses highlight the modulating role of emotional valence in fMRI studies of psychopathology (e.g., Groenewold et al., Reference Groenewold, Opmeer, de Jonge, Aleman and Costafreda2013)

Limitations and future directions

Despite the use of a large population-based sample of sociodemographical diverse families followed from birth through adolescence, integration of repeated measures of harsh parenting across childhood with linear growth curve modeling, and examination of corticolimbic activation and connectivity within the same analyses, several limitations warrant consideration. First, although our results suggest that the timing of exposure to harsh parenting is important for subsequent corticolimbic function, interpretations of our results as evidence for “sensitive periods” should be tempered. Such a claim would require repeated measures of neural function in addition to repeated measures of harsh parenting (Andersen & Teicher, Reference Andersen and Teicher2008). Procuring measures of task-based corticolimbic function in early childhood is challenging; studies rarely collect such data in children younger than 5 years due to motion and attention constraints (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Pfeifer, Fisher, Lin, Gao and Fair2015). In recent years, other imaging modalities such as resting-state or sleeping fMRI, have been successfully translated into younger populations including infants (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Pfeifer, Fisher, Lin, Gao and Fair2015); such approaches are promising for evaluating sensitive periods of environmental effects on brain development. Nevertheless, our results should be interpreted within the context of robust animal experiments documenting sensitive periods of adversity effects on corticolimbic development (reviewed by Callaghan & Tottenham, Reference Callaghan and Tottenham2016) and longitudinal structural MRI studies (reviewed by Teicher & Samson, Reference Teicher and Samson2016). Relatedly, although theories of corticolimbic development highlight early childhood and adolescence as two potential windows of vulnerability, we were unable to include harsh parenting during adolescence in our linear growth curve models. Although the FFCWS collected data at age 15, there was only one harsh parenting item that overlapped with the data collected at ages 3, 5, and 9. We included a different but comparable measure of maternal physical aggression at age 15 from the FFCWS-SAND cohort, and found that this measure of harsh parenting was not associated with concurrent corticolimbic function. Nevertheless, replications of our results would benefit from more intensive data collection across both childhood and adolescence.

Third, harsh parenting is only one type of environmental exposure thought to impact functional brain development; neighborhood- and family-level socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal psychopathology, and inter-parental conflict are just some examples of other adversities that often co-occur with harsh parenting (Green et al., Reference Green, McLaughlin, Berglund, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2010). Nevertheless, there is good reason to believe that parenting behaviors are relevant targets for understanding how environmental stress becomes biologically embedded to predict maladaptive youth socioemotional outcomes. The Family Stress Model posits that parenting behaviors (i.e., low warmth/nurturance, high harshness) mediate the negative effects of socioeconomic disadvantage on youth outcomes (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, Reference Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz and Simons1994); this model has been supported across a range of contexts – within urban and rural samples, cross-culturally, in racial and ethnical diverse samples, in two-parent and single-parent families, and using cross-sectional and longitudinal data (reviewed by Masarik & Conger, Reference Masarik and Conger2017; see Gard et al., Reference Gard, McLoyd, Mitchell and Hyde2020 for a recent application in the FFCWS). Several structural MRI studies have shown that parenting behaviors can mediate (Luby et al., Reference Luby, Belden, Botteron, Marrus, Harms, Babb and Barch2013) and moderate (Whittle et al., Reference Whittle, Vijayakumar, Simmons, Dennison, Schwartz, Pantelis and Allen2017) the effects of socioeconomic status (SES) on youth brain development. For example, using repeated measures of amygdala volume, Whittle et al. (Reference Whittle, Vijayakumar, Simmons, Dennison, Schwartz, Pantelis and Allen2017) showed that, among adolescents from low socioeconomic status backgrounds, positive parenting attenuated the age-related increase in amygdala volume. Although some research has shown that the impact of parenting behaviors on youth corticolimbic function is independent of other correlated adversities such as low family income and maternal depression (Gard et al., Reference Gard, Waller, Shaw, Forbes, Hariri and Hyde2017), more research is needed to evaluate this claim. This literature would also benefit from exploration of different types of parenting behaviors beyond physical harshness (e.g., psychological coercion, warmth).