In June 2020, CNN hosted a special called “Mayors Who Matter,” whose title and content gave a nod to the Black Lives Matter movement. Four Black women mayors—Keisha Lance Bottoms of Atlanta, Lori Lightfoot of Chicago, Muriel Bowser of Washington, DC, and London Breed of San Francisco—were welcomed to the national stage to talk about their cities’ state of affairs. Specifically, they discussed how their lived experience as Black women has influenced their leadership. Legal analyst Laura Coates, another Black woman, moderated this discussion, which spawned a provocative statement from Mayor Breed:

Let me tell you, I grew up in public housing. I grew up in San Francisco poverty, raised by my grandmother. I’ve had family members killed by police here in San Francisco, young people that I know, love and care about. When this happened, it brought up a lot of pain. And I think even though we’re mayors, I say I’m a mayor but I’m a Black woman first, because I have to remind people in San Francisco with a less than 6% African American population, that I come from the struggle of African Americans and that pain is routed in who we are.Footnote 1

In this statement, Breed brings to center stage her lived experiences as a Black woman and how these experiences are not divorced from her duties as mayor. She further claims loyalty to her Black communal ties before her appointed duty as mayor. Thinking about this explicit intersectional messaging that Breed deploys, this article considers how a competitive political environment, like the campaign trail, leads Black women leaders to employ what I call “experiential rhetoric.”

I expect that Black women candidates will leverage their lived experience, rooted in their racial and gendered identity, more than their race and gendered counterparts on the campaign trail. I also expect that the experiential rhetoric deployed by Black women will reflect Black feminist tenets. This is for three reasons. First, the literature on campaigns and elections suggests that stereotypes loom large for women leaders, which results in elevated surveillance that can only be compared with that of other minority candidates (Carroll Reference Carroll1984; Clayton Reference Clayton2010; McIlwain Reference McIlwain and Gillespie2010; Terrill Reference Terrill2015). Second, we know that Black women are more likely to advocate for raced-gendered policies than their Black male and white counterparts (Bratton, Haynie, and Reingold Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2006). Third, evidence suggests that Black women legislators talk more about race on Twitter than their male counterparts (Tillery Reference Tillery2019). Taken together, these findings indicate that questions of identity loom large for Black women in politics, inspiring them to use experience-based language.

The goal of this article is to understand whether Black women leverage their lived experiences to advocate for their policy preferences differently than other demographic groups. I argue that Black feminism provides a useful framework for understanding these dynamics—specifically, how these rhetorical choices are utilized. Black feminism is integral to my analysis because it develops theories that help frame and contextualize Black women’s life circumstances. Intersectionality, for example, is one of its most popular intellectual contributions (Nash Reference Nash2019). In so doing, Black feminism situates identity as an important political lever in community building, social justice, advocacy, and leadership—subject areas that dovetail well with political campaigns (Jordan-Zachary and Alexander-Floyd Reference Jordan-Zachery and Alexander-Floyd2018).

In the following section, I introduce literature arguing that the language, experiences, and behavior of Black women leaders are distinct, both in how they are deployed and how they are critiqued. Then, I use empirical data on three Black women mayors and their opponents to explore differences across their narratives and language. These data show that Black women politicians leverage their lived experience rooted in their racial and gendered identity—what I call “experiential rhetoric”—more than their race and gendered counterparts. I close by comparing the types of experiential rhetoric used across the mayoral campaigns, remaining cognizant of how Black feminist epistemologies may surface in this political arena.

Black Women Leaders, Behavior, and Politics

Behavior

We know that women remain underrepresented in local and appointed offices in the United States (Holman Reference Holman2017). However, Black women who run for office at the local level do relatively well, compared with the state and federal levels (Smooth Reference Smooth2006). Literature on Black women candidates tells us why these rates and representation matter, particularly when thinking about the “consciousness” that Black women leaders bring.

Black feminist scholarship actively points to organizing, care work, consciousness, and overall behavior that Black women engage in. Though its aim is not to theorize a type of feminism that fits all women, this framework helps us understand how Black women can come to a standpoint that is “characterized by the tensions that accrue to different responses to common challenges” (Collins Reference Collins1990). Through Black feminist scholarship, we understand that the leadership posited by Black women centers on “social change,” as it is motivated by their position within intersecting oppressions (Collins Reference Collins1990; Dowe Reference Dowe2020; Radford-Hill Reference Radford-Hill2000).

Collins (Reference Collins1990, 22) states that “since Black Women cannot be fully empowered unless intersecting oppressions themselves are eliminated, Black Feminist theory supports broad principles of social change that transcend U.S. Black women’s particular needs.” Though Collins articulates that Black feminist theorizing supports these principles, according to this scholarship, it is unclear whether Black women elevate these principles as a praxis. More recently, some scholars have empirically noted that this intention reigns true among Black women leaders.

In trying to understand the role of Black feminism in the Black community at large, Radford-Hill (Reference Radford-Hill2000) puts together a short list of Black feminist goals that Black women should pioneer in their line of work. One of these goals is to create a “healthy Black community” that deepens personal connections with Black people in their neighborhood. More tangibly, she articulates the importance of combating gender terrorism in child abuse, domestic violence, hate crimes, and criminal and sexual assaults (Radford-Hill Reference Radford-Hill2000, 7). Extensive literature supports the overlap between these core principles and the political behavior of Black women, particularly with respect to sexual harassment and abortion (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998; Mansbridge and Tate Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992; Simien Reference Simien2005; Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004). Scholarship by Nadia Brown (Reference Brown2014) situates this phenomenon further, by exploring the influence that Black women have had on judicial decision-making. Brown finds that Black women’s legislative decisions are distinctively different from those of other race and gender groups, especially in domestic violence prevention policies.

Identity politics often documents how gender affects the political attitudes of Black women toward abortion, sexual harassment, and the women’s movement (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998; Mansbridge and Tate Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992; Simien Reference Simien2005; Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004; Smooth Reference Smooth2006) and that race affects attitudes toward welfare and affirmative action (Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Simien Reference Simien2007). The gap that Brown fills is how Black women fare in policy preferences that activate both race and gender. For this, she examines the Maryland House of Delegates’ agenda setting by conducting in-depth semistructured interviews that do not include domestic violence questions (Brown Reference Brown2014, 91). Of those interviewed, she found that of the 22 men she interviewed, no men of any race mentioned domestic violence legislation unprompted. Meanwhile, 11 out of 15 Black women delegates mentioned domestic violence legislation unprompted (Brown Reference Brown2014, 92). She also finds that of those Black women legislators who identified domestic violence prevention as a priority, approaches to prevention vary by generation. Brown calls for further attention to the variation in Black women’s political behavior by age. Brown and other scholars specializing in raced-gendered politics want to draw attention to the myriad ways Black women’s policy preferences are rendered differently than those of other race and gendered groups.

This behavior has not gone unnoticed, as minority candidates are hyper-surveilled by white voters because of the political perception that these candidates will be responsive to a narrow base (Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995; Williams Reference Williams1989). Like skin color and gender, demographic characteristics serve as a heuristic for low-information voters and provide informational cues that support gendered and racial stereotypes (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; McDermott Reference McDermott1998). Attention to Black feminist scholarship will show that surveillance of Black women is not new and operates distinctly for this population over other racial and gendered groups.

In Black Feminist Thought, Collins (Reference Collins1990) articulates that the politics of Black women’s presence as “raced and gendered bodies” made them subject to a gaze of close scrutiny. Scrutiny aimed to control images of Black women remaining a subordinate group. Actions challenging these images by Black women are received with pushback, and in the case of Black women’s campaigns, the “politics of containment” can operate within the election process.

Women and minorities are covered in the media more negatively during the election cycle and between it (Banwart, Bystrom, and Robertson Reference Banwart, Bystrom and Robertson2003; McIlwain and Caliendo Reference McIlwain and Caliendo2011; Niven Reference Niven2004; Ward Reference Ward2016). Niven (Reference Niven2004) finds that Black men and white women in the U.S. House of Representatives receive more negative newspaper coverage than white men. Niven theorizes that the “conspicuousness of women and minorities means they are evaluated more harshly” (quoted in Ward Reference Ward2016, 322). Suppose the theory of “conspicuousness” is what drives this discrepancy. In that case, we can expect that Black women’s presence in a raced and gendered body would result in greater negativity than the presence of white men, white women, or Black men. Gershon (Reference Gershon2013) finds just that: minority men and white women received coverage comparable to white men, “but minority women received less coverage and less positive coverage than all other groups” (Ward Reference Ward2016, 155). Collins’s politics of containment is on full display in this example, with the saliency of a Black women’s candidacy judged harsher than other race and gendered bodies.

Politics and Rhetoric

Political rhetoric is an important point of consideration since it affects constituents’ policy opinions and support (Jerit, Kuklinski, and Quirk Reference Jerit, Kuklinski, Quirk and Borgida2009). Some political scientists have suggested that to win in majority-white cities, Black mayors must de-emphasize race to increase their chances of broad voter support (McCormick and Jones Reference McCormick, Jones and Persons1993). The issue of deracialization also suggests that race-specific rhetoric should be avoided by political actors (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1977; Orey and Ricks Reference Orey, Ricks and Wohl2007).

Scholarship on President Barack Obama’s governance illustrates what a “deracialized” context looks like and suggests that a framing that is “universal” produces less risk and greater reward (Perry Reference Perry2011). Political scientists have examined how Black mayors have developed rhetorical tactics to advance Black interests since the 1960s. Thompson (Reference Thompson2005) theorizes that there are two generations of Black mayoral leadership: “civil rights” mayors and “technocratic” mayors. Civil rights mayors are Black mayors who came to prominence in the late 1960s, directly after passage of the Voting Rights Act; they are best known for putting police relations at the forefront of their agenda. This first wave of Black mayors also strengthened Black civic organizations by creating “counterpublic” spaces that were not initially present. The second wave of Black mayors, known as technocratic mayors, rose to prominence in the early 1990s and ran on “managerial” and “competency” strategies, promising a more efficient local government than before. This strategy led to Black mayors supporting “color-blind” policies and rhetoric to leverage support from non-Black constituents.

Yet Black women are more likely to advocate for raced-gendered policies than their Black male and white counterparts (Bratton, Haynie, and Reingold Reference Bratton, Haynie and Reingold2006). Black women legislators also talk more about race on Twitter than their male counterparts (Tillery Reference Tillery2019). We do not see Black women shying away from race and gendered conversations. On the contrary, Black women mayors are inviting and leveraging their lived experiences in multiple ways. In the CNN special “Mayors Who Matter,” Keisha Lance Bottoms stated, “What I know is when you’re leading, not to be authentic is exhausting and people don’t elect us to be something that we’re not, they elect us to be who we are and all that entails and for me, it’s a Black woman and I wear that proudly and I own it each and every day”Footnote 2

Other Black mayors have reaped great rewards by explicitly leveraging their racial identity during campaigns. The first African American mayor of Chicago, Harold Washington, used the campaign slogan “It’s our turn” to present himself as a symbol of Black pride and progress (Metz and Tate Reference Metz, Tate and Peterson1995; Perry Reference Perry2011, 570). Even with the risks outlined earlier, racialized language is used to galvanize Black voters. Thus, the voter base of these cities matters when measuring said risks. With inconsistent literature on how racialized language affects candidates’ campaigns, the extent to which these risks reap the rewards is still unclear (Stephens-Dougan Reference Stephens-Dougan2021). However, this article is most interested in exploring the ways Black women mayors articulate a form of resistance by leveraging their lived experiences in a competitive context that could benefit them if censored.

Thematic Framework and Methodology

Hypotheses

I use the term “experiential rhetoric” to describe how lived experiences can be used to persuade in speeches. Though “experiential” and even “lived experience” can encompass a variety of speech approaches, I depend on Black feminist usage of the term “lived experience” to orient how I am coding these speech tactics. While many, and quite possibly all, candidates mention their experience working in a government sector to influence voters, not every candidate will articulate the personal and distinct situations that accompany living in a raced and gendered body. Further, “lived experience” is situated differently in Black feminist theory than in other feminist and racialized theories.

Black feminist theory was born out of the emergent need for self-definition and empowerment (Collins Reference Collins1990). Scholarship, history, and storytelling left the perspectives of Black women absent at most, and as an asterisk at best. Black feminist theory is a platform in which Black women’s experiences are at the center, as other theoretical works create a narrative of Black women that is both unfounded and “to their use and our [Black women’s] detriment” (Lorde Reference Lorde1984, 34). Central to the Black feminist epistemology that Collins (Reference Collins1990, 266) claims comes in four dimensions is “lived experience as a criterion of meaning.” The other three dimensions are the use of dialogue, the ethic of personal accountability, and the ethic of caring (James Reference James2016, 24). Black feminist theory accounts for narratives left at the margins and calls for them to come to the forefront. It acknowledges that the intersections of multiple oppressions create a standpoint unique from other groups and that experiences do not translate uniformly to different races and gendered bodies.

Feminist scholarship can be attentive to differences across lived experiences, the way that Black feminism is, by reflecting on the ubiquitous nature of race as a “metalanguage” (Gore Reference Gore2017; Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1992). Higginbotham (Reference Higginbotham1992, 252) depicts race as an “all-encompassing effect on the construction and representation of other social and power relations, namely, gender, class and sexuality.” Higginbotham narrates the historical and empirical grounding of race as a metalanguage by using slavery as a case in point. As it relates to gender, Higginbotham (Reference Higginbotham1992, 258) states, “Black women experienced the vicissitudes of slavery through gendered lives, and thus different from slave men. They bore and nursed children and performed domestic duties—all on top of doing fieldwork.” Higginbotham uses the Jim Crow era for a class analysis, a time when Black people who could afford first-class seats in railroad cars were denied access to them and sat “in a Jim Crow coach with no flush toilet, washbasin, running water, or soap” (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1992, 260).

Though we are no longer living in the era of chattel slavery or Jim Crow, race as a metalanguage is still omnipresent. A contemporary illustration of race as a metalanguage is the crisis of Black maternal mortality (Nash Reference Nash2021). A ProPublica report received widespread attention for an article that articulated, “Even when accounting for risk factors like low educational attainment, obesity and neighborhood poverty level, the city’s black mothers still face significantly higher rates of harm … Of note, college-educated black women fare worse than women of all other races who never finished high school. And black women in the wealthiest neighborhoods do worse than white, Hispanic and Asian mothers in the poorest ones” (Waldman Reference Waldman2017).Throughout history and time, the Black women’s experiences lay bare the differentiated positionalities that spawn a different experience from their race and gendered counterparts.

For these reasons, I believe that Black women candidates will leverage their lived experience, rooted in their racial and gendered identity, more than their race and gendered counterparts on the campaign trail ( H 1 ). I also believe that the experiential rhetoric deployed by Black women will evince Black feminist tenets ( H 2 ).

Data Collection

Nonwhite women serve as mayors at similar rates as white women (Holman, Reference Holman2017), and though nonwhite mayors primarily serve in smaller cities (Hardy-Fanta et al. Reference Hardy-Fanta, Lien, Pinderhughes and Sierra2016; Swain and Lien Reference Swain and Lien2017), 20 Black women served as mayors of cities with populations of more than 50,000 in 2019 (CAWP 2019). Table 1 shows the 11 Black women who served as mayors in cities with populations over 100,000 in that year.

Table 1. Black women mayors in cities with populations over 100,000 in 2019

Note: This is a list of candidates who’s reference numbers were above the cities average. A full list of the candidates and their experiential rhetoric average can be seen in the appendix.

Source: CAWP (2019).

With much of the literature on Black women’s behavior situated at the state level, there is an opportunity to build upon this work by studying the leadership of Black women at the local level. For scholars who are interested in the welfare of the Black community, the local landscape provides crucial insights into mayoral fiscal allocations and police powers (Taylor Reference Taylor2016), segregationist zoning and its effects on communities (Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018), and Democratic participation (Burch Reference Burch2013). Understanding local politics and the leaders who shape it is indispensable to the discipline.

For this article, I utilize campaign debates from the mayoral races of Keisha Lance Bottoms, Lori Lightfoot, and Muriel Bowser. I collected a total of 62 debates generated from YouTube, Facebook Live, and grassroots organization websites. These transcripts encompass mayoral debates across the entirety of these three candidates’ campaigns, including debates from the runoff elections. Bottoms’s campaign started in the winter of 2017, Lightfoot’s began in the summer of 2018, and Bowser’s started in the winter of 2013. I analyzed 23 transcripts for Bottoms, 19 for Lightfoot, and 20 for Bowser.

The asynchrony of their campaigns, along with the heterogeneity of the debate contexts and the cities they would govern, make these three cases particularly valuable for examining Black women leaders’ rhetorical campaign strategies. Not only are Bottoms, Lightfoot, and Bowser governing three of the largest cities in the United States, but these cities also house substantial Black populations. If Black women candidates leverage their lived experience in campaigns, my hypothesis is that they are most likely to do so when addressing electorates that largely mirror their own racial identity. Further, these campaigns were chosen over those of other Black women mayors in the United States because they govern majority-minority cities with nonwhite populations over 45% and Black-specific populations over 30%. Latoya Cantrell of Charlotte, North Carolina, would have been a great addition. However, Atlanta, Chicago, and Washington, DC, all have stronger heritages as Democratic bastions, which, given the link between party affiliation and minority electoral success, made these cities more conducive to the lens through which I conduct my analysis.

Methodology

By looking at 62 transcripts of debates ranging from 45 minutes to up 2 hours and 30 minutes, I conducted a content analysis using NVivo, a qualitative data analysis tool. Since NVivo is more like a data management tool than a standard machine coding mechanism, the transcripts, codes, keyword searches, and speakers were generated and identified by hand. It is a labor-intensive process, with the NVivo platform aiding in the analysis after setup. Using the candidate as the unit of study, I reported the race, gender, age, and location (Atlanta, Chicago, and Washington, DC) of 37 candidates in total. I did a keyword sweep across all candidates with words associated with their lived experience, partisanship, and profession.

The raw data collection was driven by the number of times each candidate spoke on the campaign trail. Of the candidates, there were three Black women, excluding Bottoms, Lightfoot, and Bowser; nine white men; four white women; and 16 Black men. One Black woman candidate dropped out of the race before the general election, and the second Black woman did not make it to the runoff election. In comparison, only one white man did not make it to the general election of the nine. I standardized these data by dividing the sum of their lived experience count by the number of times they spoke on the campaign trail. The result (a number between 0 and 1) for each candidate becomes the “experiential rhetoric” percentage value that I use for my analysis.

Table 2 lists the top candidates who received reference numbers at or above the average for each city pool. The reference numbers refer to how often the candidates spoke in the data set collected. Ultimately, a lager reference number indicates how much data was collected for each candidate’s rhetoric, creating more accurate results. These results will be discussed at length later in the article.

Table 2. Candidate list above city average references

Note: A full list of the candidates and their experiential rhetoric average is available in the appendix.

Though I coded for the candidates’ lived experience, partisanship, and profession, I am most interested in how these candidates leveraged their lived experience as a means of persuasion relative to Black women. Table 3 provides an example showing the distinction between how each term is coded and what I designate as “lived experience” relative to “partisanship” and “profession.”

Table 3. Examples of general coded categories

Note: KLB = Keisha Lance Bottoms; LL = Lori Lightfoot; MB = Muriel Bowser.

Using more than 20 keywords associated with lived experience, I tallied how often a candidate mentioned those keywords and summarized the outcomes. Keywords such as “I grew,” “my daughter,” and “I live” were identified for this study through the creation of a running list of terms during the transcript-editing process.Footnote 3 This is the most effective mechanism to understand how the candidates leveraged their lived experience, exploiting the use of common prepositions and verbs while also considering the varied ways candidates speak and express themselves. Once I calculated the sum, I standardized this number by dividing each candidate’s count by the number of times they spoke in the data collected. This number is easily identified in NVivo, as each candidate, also known as a case, has their own “reference” number. The reference number refers to the number of times NVivo recorded a candidate speaking in the transcripts.

The second half of the coding process involved creating Black feminist tenet designations to best understand and group Black women mayor’s rhetorical decisions. Simien and Clawson (Reference Simien and Clawson2004) chart the core tenets that I looked to encode.

The theoretical classifications that make up my tenets are “collective action,” “intersectionality” (as an analytic), “Black mothering,” and “lived experience.” Collective action was coded as recognition that an individual’s life chances are inextricably tied to the group and that collective action is a necessary praxis (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Wing Reference Wing1990). Intersectionality was coded as particular attention to systemic inequalities and overlapping social vectors such as race, gender, and class (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). When a statement leveraged experiences as a mother, caring for children, raising a family, and so on, I coded it as Black mothering. And finally, lived experience is the recognition and articulation of a lived circumstance and/or individual experience and how it influences their perspective. It was important for this analysis to have an ambiguous term like “lived experience” to account for the unique experiences that are either exclusive to that mayor or difficult to predict. Functions called “nodes” were created using the feminist tenets I outlined earlier, and the speeches were coded according to those themes. For phrases that fall under multiple tenets, I coded them as such and placed them in the proper nodes in NVivo. Figure 1 provides an example of a coded excerpt in NVivo.

Figure 1. Coding snapshot.

Experiential Rhetoric in Mayoral Campaigns

The Bottoms Campaign in Atlanta

Atlanta has long been considered the mecca of Black business and political empowerment. These accolades are largely attributable to the political leadership of Atlanta’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, who was elected in 1973. Jackson was the grandson of a civil rights leader and campaigned on a strategy to guarantee better conditions for Black people living in Atlanta. This was in stark contrast with the incumbent mayor, Sam Massel, who often “alienated [B]lacks by appealing to the fears of white voters” (Owens and Rich Reference Owens, Rich, Browning, Marshall and Tabb2003, 209). In 1973, an extensive charter reform provided greater executive powers to the mayor by weakening the city council’s previous shared power.Footnote 4 With this shift, Atlanta in the 1970s was soon controlled by Black leadership in city hall, the city council, and the board of education. This legacy was sustained for years after and continues to have influence today.

Keisha Lance Bottoms took office in 2018 during the federal corruption investigation of former mayor Kasim Reed. Reed’s administration was accused of bribery and fraud against his team members, including his financial officer, procurement officer, and deputy chief of staff (Nobles Reference Nobles2021). These allegations followed Reed out of office and subsequently “cast a shadow” over Bottoms’s tenure and left candidates with the burden of explaining how they would be better. Bottoms was Reed’s trusted ally on the Atlanta City Council, and as their relationship tainted the public’s perception of how she would govern once in office, Bottoms aimed to distinguish herself from Reed’s administration. On the campaign trail, Bottoms often rebutted accusations that she was “Reed’s third term” on the campaign trail.

The transgressions of Reed’s administration, coupled with less than favorable federal and state election outcomes, created challenging conditions for candidates to address. Not surprisingly, the Donald Trump administration produced problems of its own for the city of Atlanta and several other Democratic cities across America as he threatened to cut federal funds amid unfavorable immigration enforcement. In a memo released to the Office of Budget Management, Trump stated that “my administration will not allow federal tax dollars to fund cities that allow themselves to deteriorate into lawless zones” and would instead defer federal funding to “sanctuary cities” (Haberman and McKinley Reference Haberman and McKinley2020). This posed a threat to cities across the United States, especially cities governed by Black mayors, many of which struggled to govern amid a pending financial distress (Thompson Reference Thompson2005).

These issues surfaced throughout the campaign, and candidates were tasked with navigating and providing answers to them. As they did so, candidates leveraged rhetorical strategies that they believed would resonate most with voters and earn their votes. My findings suggest that Bottoms leveraged her lived experiences more than her race and gendered counterparts did throughout the campaign.

On average, candidates in the Atlanta mayoral race leveraged their lived experience 11.23% of the time. In the 255 times that Bottoms spoke throughout the debates, she leveraged her lived experience 28.6% of the time, well above the average. Out of the 12 candidates running, only one candidate, Black male city council president Ceasar Mitchell, cited their lived experience nearly as often as Bottoms, at 24.7% of the time. Lamon King, another Black male candidate who appeared in two debates and spoke 38 times, leveraged his lived experience 18.4% of the time, placing third, after Bottoms.

Table 4 illustrates how Bottoms and a few members of the candidate pool responded to the same question on the campaign trail.

Table 4. Atlanta findings

In this example, we see that Mitchell invoked his lived experience, with his close family members having deep associations with the Atlanta Public School system, just as Bottoms expressed with her family ties. They presumably did so to convince the audience that these familial ties imbue them with a unique perspective that distinguishes them from other candidates on the issue of public education—the implication being that they would be better situated to improve the public school system as mayor.

By looking at the averages across race and gender, Black men leveraged their lived experience 13.4% of the time, white women leveraged their lived experience 6% of the time, and white men leveraged their lived experience 14.2%. Bottoms was the only Black woman in the running.

The Lightfoot Campaign in Chicago

Chicago is distinct from other U.S. cities for having evidence of the longest-running Democratic machine, with machine politics dominating the city for over half a century. The Daley machine is considered the most prominent, reigning over Chicago from 1955 to 2011. After Richard M. Daley stepped out of office in 2011, Rahm Emanuel, the former chief of staff for President Barack Obama, became the 55th mayor of Chicago from 2011 to 2019. Many Chicago residents showed dissatisfaction with Mayor Emanuel’s administration, with much of this dissatisfaction centering on Chicago school and health service closures. WBEZ Chicago South Side reporter and author Natalie Moore (Reference Moore2016, 204) stated that “some voters viewed him as a get-things-done guy who cleaned up Daley’s financial quagmire. Others saw him as a vindictive power player who closed schools and is beholden to the rich and to corporate interests.”

When Emanuel stepped down, many mayoral candidates took the opportunity to center their campaigns on breaking away from the Democratic machine to respond to all Chicago constituents, not only middle-class interests. A diverse pool of candidates put their hats in the ring, resulting in a historic election between three Black women candidates: Lori Lightfoot, Amara Enyia, and Toni Preckwinkle.

Candidates campaigned to become the next mayor to follow behind the legacy of Emanuel and Washington. Though Washington was mayor for only two terms, he was Chicago’s first African American mayor. He was best known for racially diversifying the city government, creating the ethics commission to combat corrupt government practices, and leading the fight toward redistricting to account for better Black and Hispanic representation.

Similar arguments were articulated more than 30 years later in the 2019 mayoral race. In answering these challenges, my findings suggest that Lightfoot leveraged her lived experience more than her race and gendered counterparts throughout the campaign.

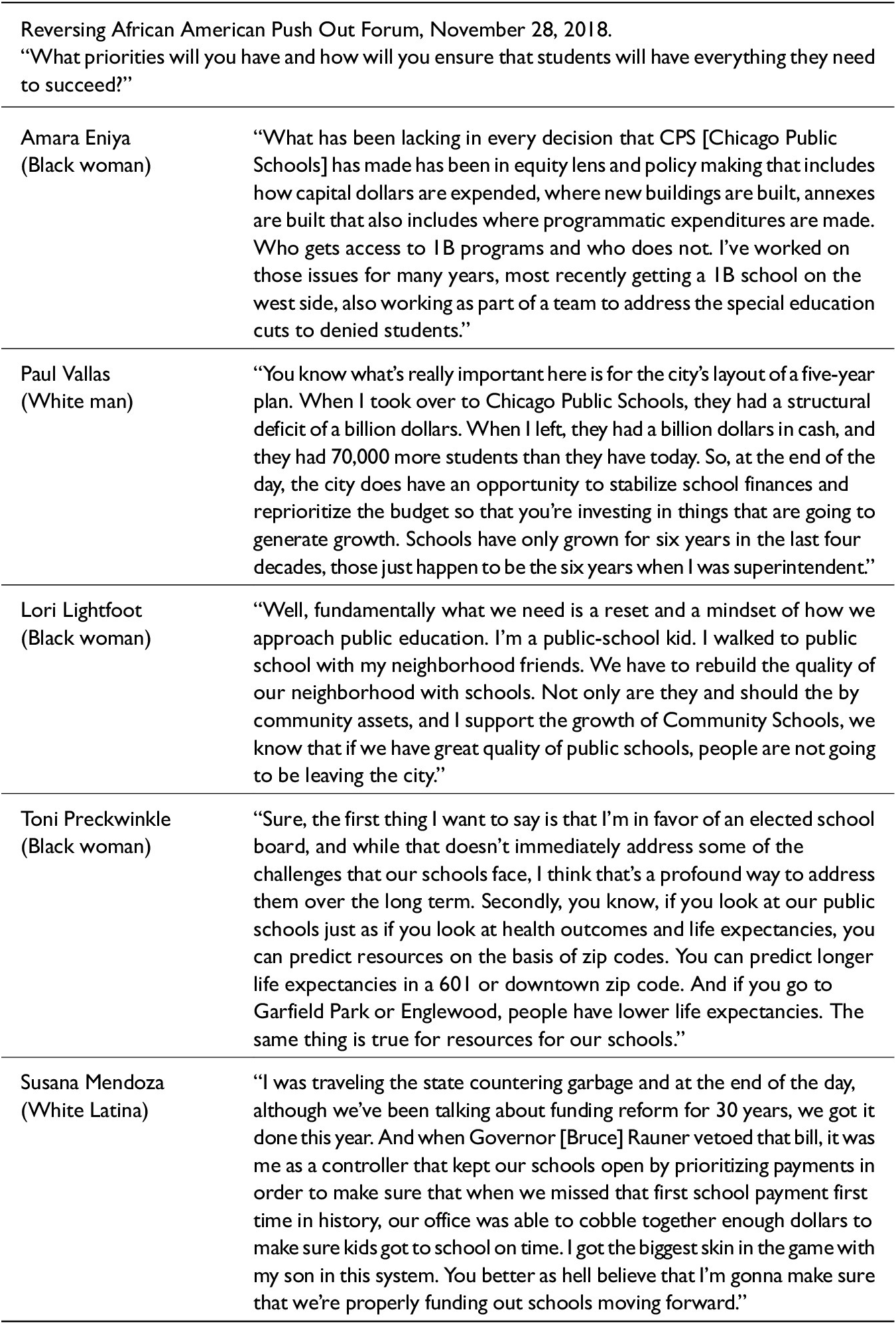

Table 5 illustrates how Lightfoot leveraged her lived experience relative to the other mayoral candidates in Chicago.

Table 5. Chicago findings

While Bottoms was the only Black women running in the Atlanta elections, Lightfoot faced a few women of color adversaries, including Susana Mendoza, Amara Enyia, and Toni Preckwinkle. In the example in Table 5, we can see variations in how each woman, alongside white American politician Paul Vallas, responded to the same question.

Lightfoot used experiential rhetoric when mentioning that she was a public-school kid—grounding her desire to improve the lives of children and families with similar backgrounds. Mendoza used experiential rhetoric by invoking her son, hoping to validate her vested interest in wanting a better school system for all children, as this would imply better conditions for her son, too. Both these expressions attempted to signal to voters that the candidates’ personal attachments to the issues at hand and the implied vigor with which they would try to ameliorate them for the city of Chicago.

On average, candidates in the Chicago mayoral race leveraged their lived experience 13.2% of the time. Black men leveraged their lived experience 8.3% of the time, and white men leveraged their lived experience 12.1% of the time. Lightfoot leveraged her lived experience 24.3% of the time, which is double the average in the Chicago mayoral election. Though her experiential rhetoric count is slightly lower than that of Bottoms in Atlanta, Lightfoot was competing as the only candidate in my data set who identified with three marginalized groups: Black, lesbian, and woman.

The Bowser Campaign in Washington, DC

The District of Columbia had one of the highest percentages of African Americans of any U.S. city in the twentieth century. It attracted Black Americans to the city because of its Black educational prospects, both at the collegiate level (with Historically Black Colleges and Universities) and in secondary education (McQuirter Reference McQuirter2003). Black politics has a rich history in Washington, DC. Its inception as the District of Columbia, separate from Maryland and Virginia, was born of local pressures spurred by activists taking part in the 1963 March on Washington and the 1968 riots, triggered by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. The assassination was the tip of the iceberg, as many Black Americans were dissatisfied with the consistent segregation of schools and the federal government’s “abandonment” of the city (McQuirter Reference McQuirter2003). The federal government announced Washington DC’s “home rule” and appointed its first mayor, Walter E. Washington. The city reelected Washington as mayor in 1974, beginning a consistent streak of Black mayoral governance. In this way, Washington, DC is distinct from the other cities explored in this study as the only major U.S. city solely governed by Black mayors.

As the first mayor of Washington, DC, Washington was tasked with addressing grievances that essentially had gone ignored. Poorly equipped schools, crime, debilitated public housing, and unemployment were some of the many issues. To tackle corruption, Washington appointed the first Black police chief in Washington, DC, hoping that it would integrate city officials and build trust in local communities.Footnote 5 His governorship was favorable until the reelection period introduced Washington residents to strategies that better reflected their interests. Marion Barry ran in 1976 on the promise that life would be “better” under his administration (Massimo Reference Massimo2018). Though Barry campaigned on a civil rights agenda, it served him well in building coalitions across several groups. Many liberal whites saw the issues he sought to address as transcending race. After being considered an underdog, Barry won the primary election against Washington and, soon after, the general election in 1978. Barry was a grassroots activist, soon known as DC’s “Mayor for Life” (Massimo Reference Massimo2018). Barry served as mayor from 1978 until he dropped his reelection bid in 1989 after he was charged with cocaine possession. He was soon arrested, prosecuted, and served six months in federal prison.

Sharon Pratt Kelly, the first Black woman mayor of DC, took office in 1990, prevailing against three well-known city council members. Kelly’s victory, however, was short-lived, as she only served one term in office before Barry came back to run for and win reelection in 1995.

Several Black mayors have taken office since Barry’s tenure, but, like several other cities in America, candidates were tasked with articulating how city ills would be effectively addressed in their administration. Experiential rhetoric is a powerful tool to do so, as it seeks to invoke commonalities between politicians and prospective voters. In majority-minority cities like Atlanta, Chicago, and Washington, DC, conveying kinship with the “Black” experience can meaningfully animate voters who identify with that experience, as Lightfoot and Bottoms exemplified. However, my findings suggest that Muriel Bowser leveraged her lived experiences less than other candidates while discussing her plans on the campaign trail.

Table 6 shows how Muriel Bowser and other candidates in the race responded to the same question.

Table 6. Washington, DC, findings

On average, mayoral candidates in Washington, DC, leveraged their lived experience 10.9% of the time. Bowser leveraged her lived experience 8.6% of the time, making her the only Black woman elected mayor in my study who leveraged her lived experience less than the overall average. We can see this in Table 6, when she was asked about charter school moratoriums. Bowser opted to address the questions using language devoid of emotions and personal context (similar to most of her peers), while Rita Joe Lewis, another Black woman on the campaign trail, chose to make a clear personal tie with the DC school system. Due in large part to Lewis, Black women, on average, still leveraged their lived experience more than other race and gendered groups in Washington, DC. Black men leveraged their lived experience 10% of the time, and Black women leveraged their lived experience 15.4% of the time. Though I can only hypothesize as to why Bowser did not leverage her lived experience nearly as much as Lightfoot and Bottoms, it would be consistent with the literature if Bowser felt pressure to deracialize her rhetoric because of the nature of the mayoral race and the composition of the city.

Though Washington, DC, is still considered a majority-minority city, with a population composed of 45% Black people, Bowser and Lewis were the only Black women in my study to be subject to interparty competition. In Atlanta and Chicago, Bottoms’s and Lightfoot’s races were largely single-party affairs, as most candidates identified as Democrats (Mary Norwood in Atlanta, who identified as an independent, is the only exception).

Against this backdrop, it is possible that Bowser thought it best to hew closely to a postracialized rhetoric, which could lead to positive candidate evaluations from white voters regardless of partisanship affiliation (Wamble and Laird Reference Wamble and Laird2020). As Washington, DC, has undergone a drastic demographic shift in the last decade, with one of the fastest-growing white populations in the United States (second to Idaho),Footnote 6 it is possible that Bowser wanted to inoculate herself from any racial stereotypes that racialized rhetoric may have engendered.

To be clear, experiential rhetoric is not synonymous with racialized rhetoric, as many candidates on the campaign trail have evoked their lived experience without mentioning race—Bowser being one of them. However, because Bowser is a Black woman, it is probable that she refrained from articulating her lived experience more often to avoid her language being racialized by voters who already carry predispositions about Black candidates (Carroll Reference Carroll1984; Clayton Reference Clayton2010; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; McIlwain Reference McIlwain and Gillespie2010; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2011; Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995).

Comparing Experiential Rhetoric across Mayoral Campaigns

Using data from all three candidates across Atlanta, Chicago, and Washington, DC, Black women leveraged their lived experience, on average, 11.8% of the time. Black men came in a close second at 11.6%, white women with 9.4%, and white men with 8.8%. Black women, particularly Bottoms and Lightfoot, leveraged their lived experience nearly double the average of their race and gendered counterparts running against them. In this section, I discuss the Black feminist tenets that Bottoms, Lightfoot, and Bowser deployed on the campaign trail. Using collective action, intersectionality, Black mothering, and lived experience as tenets, I provide greater insight into the content of experiential rhetoric in the campaigns of Black women mayoral candidates.

Collective Action Rhetoric

Bottoms and Lightfoot often articulated to voters that their fates are tied, signaling that they both want the same things (see Table 7). Bottoms mentioned that she wanted the community of Atlanta to be safe and fruitful for her children, but it could not be “if it’s not for each of your families.”Footnote 7 Whether realized or not, they are deploying rhetoric that references a “linked fate” phenomenon, in which an [Black] individual recognizes that what happens to the [Black] group as a whole is inextricably tied to the fate of one’s own (Dawson Reference Dawson1994, 80). This phenomenon is historically grounded in the treatment Black people were subjected to, which Dawson traces back to slavery and its continued relevance today. Similarly, Lightfoot referenced her parent’s treatment in the “segregated south” and how that “soul-crushing” reality solidified a consciousness that they passed down to Lightfoot. This consciousness is rooted in advocacy for oneself and others.

Table 7. Collective action rhetoric

Further, this recognition is well situated in the understanding of Black feminist consciousness, as the “reality” of Black women’s lives is subjected to discrimination based on both race and gender (Collins Reference Collins1990; Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004). Central to Black feminist thought is the understanding that to resist oppression, self-definition must be actualized within oneself and the group, empowering the collective to act on an “agenda for change” (Collins Reference Collins1990, 30; Lorde Reference Lorde1984).

Intersectionality (as an Analytic) Rhetoric

I distinguish intersectionality and intersectionality as an analytic because of the recent commodification and historical genealogies tied to the term (Nash Reference Nash2019) (see Table 8). As Nash (Reference Nash2019), Hancock (Reference Hancock2007, Reference Hancock2011), Cooper (Reference Cooper, Disch and Hawkesworth2015), and others have argued, intersectionality has been used in numerous interdisciplinary projects, spurring debates about the understanding of the term and its correct usage. With its multiple genealogies across disciplines, I align my usage of the term with Crenshaw’s definition of intersectionality as an analytic “fundamentally rooted in Black women’s experiences” that both theorizes and accounts for systems of power (Nash Reference Nash2019, 9; see Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991).

Table 8. Intersectionality as an analytic rhetoric

In articulating their lived experience, Lightfoot and Bowser shed light on the powers of oppression operating against them in life and during the campaign. Lightfoot often mentioned the discrimination she faced as a Black lesbian. At the Women’s Mayoral Forum on February 6, 2019, she gave the audience a detailed recollection of her experience of “sexual harassment” and “discrimination” when she worked for the police department. Lightfoot said, “Here I am, a new person, I’m a woman, I’m younger than most of the people that are out here in the scene, and there was a commander who every time I showed up was harassing me and tried to make fun of me and humiliate me in front of all the other men.”Footnote 8 She further claimed that this treatment was not exclusive to her, as every woman she had ever known had “suffered through this in some way.” Here, Lightfoot addresses the ever-present sex-based workplace discrimination, deploying an intersectional analysis of her experience working for the police academy.

Though all these examples are considered a “lived experience,” I also sought to include a code that is not tightly bound by a set of conditions (see Table 9). This code would benefit all candidates equally and account for any unique circumstances that are difficult to predict. The only requirement was an experience exclusive to the individual that is not only tied to their professional experience. Professional experience is expected, as all candidates have incentives to mention how long they have worked for the city council or supported the Democratic Party. Still, not all candidates divulge the more private parts of their livelihoods.

Table 9. Lived experience rhetoric

Of the three candidates I analyze in this article, Bowser is the least likely to use experiential rhetoric in the way I describe it. While Bottoms and Lightfoot are most likely to use race-gendered language and personal narratives avidly, Bowser is more reserved on this front. However, when Bowser uses experiential rhetoric, she couples it with a discreet reminder to the audience of her identity and her capabilities to lead.

On March 17, 2014, Bowser and her opponents campaigned on the Kojo Nnamdi Show, a radio-television show based in Washington, DC. Bowser was asked, “Where do your passions lie” on the issue of DC statehood.Footnote 9 Bowser responded with conviction that she has a passion for the most important issues for residents in the District of Colombia and offered a prime example. She briefly used her experience of being incarcerated for 17 hours to show that she is willing to go to great lengths for the most critical matters. This particular issue was women’s reproductive health. Bowser went further to say that though she has what it takes, she is also “pragmatic” and capable of strategically targeting Congress members to make DC statehood a priority.

Black Mothering Rhetoric

Bottoms dominated the rhetoric on Black mothering (see Table 10). Though all the mayors discussed in this article are Black mothers, Bottoms often referenced her children when discussing her policy preferences, her motivations for running, and her commitment to bettering Atlanta. What makes this particularly important and worthy of coding is the deep-seated understanding of Black motherhood in Black feminist thought. Texts like Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens (Reference Walker1983), Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born (Reference Rich2021), and Toni Morrison’s Sula (Reference Morrison2004) are some of the many Black feminist texts that wrestle with the complicated and vulnerable realities of Black motherhood. Integral to understanding Black motherhood is a distinct mindfulness of community well-being and care work. Dani McClain’s We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood (Reference McClain2019) articulates the central thesis that “Black motherhood is a distinctive formation constituted by its political life, its fundamental commitment to a ‘we.’ Black motherhood is a collective formation, it is fundamentally invested in the thriving of the totality, because it is born from conditions that are, as other have argued, ‘life or death’” (Nash Reference Nash2021, 155).

Table 10. Black mothering rhetoric

McClain acknowledges that giving birth to life is contingent on community conditions, and maintaining life is contingent on community conditions—both burdens to bear for Black mothers. It is life-changing work that has the power to inform decision-making (Wright Reference Wright2022; Wright and McNeely Reference Wright, McNeely, Brown and Gershon2023) and political motivation (McSpadden Reference McSpadden2016). Bottoms articulated just that when she said, “I have four children, and they are the four reasons why I am running for Mayor.”Footnote 10

Conclusions and Future Direction

Amid local, state, and national crises, many of which were associated with COVID-19, Bottoms conceived and executed a successful mayoral campaign. On the trail, she spoke vividly about mothering the four children she adopted and her decision to do so because of pregnancy complications with her husband, Derek Bottoms. Bottoms credits her run for office for securing a better future for her children. Her personal narratives, messages, and perspectives on the Black experience resonated greatly with Atlanta, and ultimately, the cities that Black women politicians govern, especially during the era of Black Lives Matter (Davies Reference Davies, Brown and Gershon2023; Wright and McNeely Reference Wright, McNeely, Brown and Gershon2023). However, Bowser of Washington, DC, did not embrace experiential rhetoric at the same rate as the other Black women candidates in my data set. Though I posit that the changing demographics of Washington, DC, could be the impetus for this decision, further empirical analysis of Bowser as a leader and Washington, DC, as a city is needed to validate this hypothesis.

The primary goal of this article is to grapple with the realities of language and rhetoric, which manifest differently for Black women on the campaign trail and in office. Political science scholarship has acknowledged that minority candidates’ political argot is significantly scrutinized. However, there has not been enough exploration of how Black women navigate being under the political microscope and how this scrutiny can be challenged in varying contexts, like majority-minority districts.

Atlanta, Chicago, and Washington, DC, are all majority-minority Democratic cities. This is by design, as Black women often lead Democratic cities and have a greater likelihood of winning office in majority-minority districts. I chose to scrutinize Keisha Lance Bottoms, Lori Lightfoot, and Muriel Bowser because they were mayors of three of the largest cities in the United States with a substantial Black population. With the likelihood of Black interests at the forefront, this dynamic was also beneficial in examining how Black feminist tenets are deployed in campaign debates, as the latter half of this article explores. I considered this context to be rife with opportunities to analyze the language use of Black women leaders in their highest-stakes and most politically vulnerable moments.

Experiential rhetoric serves as the best framework to understand these rhetorical approaches. Born out of Black feminist scholarship, experiential rhetoric acknowledges the political power of lived experiences, especially and inexorably for Black women and within marginalized communities. To be clear, I do not argue that Bottoms, Lightfoot, Bowser, or other candidates consider themselves to be feminist by using experiential rhetoric, but rather, it is an admission that experiential rhetoric is and can be used in the political sphere as a rhetorical and winning strategy. However, my findings suggest that Black women leaders deploy experiential rhetoric more than their race and gendered counterparts on average. Future research should explore the motivation behind this rhetorical tactic and the extent to which it is driven by the discriminatory sensibilities of the constituents they seek to govern as well as societal pressures.

The limitations of this study include the inability to measure whether these expressions manifest in a larger sample of Black women mayors, the degree to which these findings are sustained in non-majority-minority districts, and the impact of heterogeneity in the candidate pool. With respect to the last limitation, it is notable that Bottoms elevated her identity as a Democrat most often during the runoff election debates with Mary Norwood, a white woman and an independent, for example. Nonetheless, this article contributes in novel ways to research on the race and class cleavages that often create divides on policies around city planning and urban development. In using experiential rhetoric, I argue, Black women candidates are employing a specific type of rhetorical strategy to convince voters that they are best suited to bridge these divides.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000077.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Nick K. S. Johnson, Alvin Tillery, Jennifer C. Nash, Reuel Rogers, Tabitha Bonilla, Matthew Nelsen, Justin Zimmerman, Dara Gaines, Michelle Bueno-Vasquez, and Kumar Ramanathan for their thoughtful insights on this work, support in this endeavor, and kind presence in my life. I would also like to thank the participants in the 2021 APSA convening and the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy.