A U-shaped association between alcohol intake and the risk of cardiovascular( Reference Costanzo, di Castelnuovo and Donati 1 ), cancer( Reference Jin, Cai and Guo 2 ) and non-cardiovascular–non-cancer mortality( Reference Di Castelnuovo, Costanzo and Bagnardi 3 ) has frequently been reported. The pathological effects of excess alcohol consumption have been widely studied in many different tissues such as the myocardium( Reference Urbano-Marquez, Estruch and Navarro-Lopez 4 , Reference Fernandez-Sola, Estruch and Grau 5 ). Moreover, deleterious effects of heavy drinking have also been reported in epidemiological studies( Reference Corrao, Bagnardi and Zambon 6 ). Low-to-moderate alcohol intake when compared with abstention or heavy drinking is usually assumed to reduce the risk of major chronic disease and all-cause mortality. The mechanisms proposed to explain this inverse association with moderate alcohol intake include increases in serum HDL-cholesterol, inhibition of platelet production, activation and aggregation, increased fibrinolysis( Reference Rimm, Williams and Fosher 7 ), beneficial effects on endothelial function and inflammation( Reference Estruch, Sacanella and Badia 8 ), and enhanced insulin sensitivity( Reference Facchini, Chen and Reaven 9 ). However, drinking alcoholic beverages involves other dimensions beyond the precise amount of alcohol intake. For example, alcohol intake can be conceptualised as an element that forms part of an overall dietary pattern or as a substance consumed in order to seek psychoactive effects. In the culinary tradition of Mediterranean countries, alcohol intake used to be moderate, spread out over the week, preferably from wine, consumed with meals and without excess( Reference Heath, Grant and Litvak 10 ), contrary to the binge-drinking pattern of concentrated consumption of spirits( Reference Valencia-Martin, Galan and Rodriguez-Artalejo 11 ). Our hypothesis was that a high adherence to an overall healthy alcohol-drinking pattern involving many dimensions of drinking behaviour can reduce all-cause mortality, beyond the reduction observed for moderate alcohol intake. In this context, we developed a score to capture the conformity to the traditional Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern (MADP) and tested its relationship with the risk of all-cause mortality.

Methods

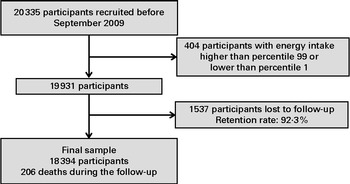

The ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (University of Navarra Follow-up Study) (SUN) Project is a dynamic and multi-purpose cohort study entirely composed of highly educated subjects (university graduates). Up to September 2009, 20 335 subjects answered the baseline questionnaire. Information was updated biennially. For the present analysis, 404 participants with total daily energy intake out of percentiles 1 and 99 were excluded. Among the remaining 19 931 participants, 18 394 were successfully followed up (overall retention rate 92·3 %; Fig. 1). The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Navarra. Details of the design and methods of this cohort study have been described elsewhere( Reference Seguí-Gómez, de la Fuente and Vázquez 12 ).

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the study participants in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project 1999–2012.

Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern

Alcoholic beverage consumption (red wine, non-red wine, beer and spirits) and other information about alcohol-drinking habits during the year preceding enrolment were gathered in the baseline assessment, including a validated 136-item semi-quantitative FFQ( Reference Martin-Moreno, Boyle and Gorgojo 13 ).

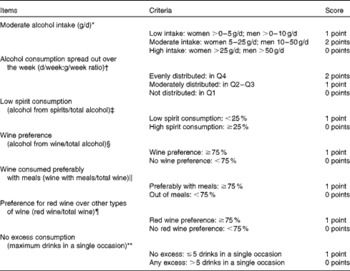

A 0- to 9-point score was developed to capture the conformity to the traditional MADP. We scored seven items (Table 1): (1) moderate total alcohol intake – positively scored with 2 points if the consumption was 10–50 g/d (men) or 5–25 g/d (women)( Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Bamia 14 ); intakes below this range were assigned 1 point and intakes above this range were assigned 0 points; (2) alcohol intake spread out over the week – (i.e. the total weekly amount of alcohol ingested was evenly distributed across the days of the week) we computed the ratio between the number of drinking days per week and total g/week of alcohol intake and categorised it in quartiles; we assigned 2 points to participants in the highest quartile (most days in a week and lower total amount), 1 point to those in the second and third quartiles and 0 points in the lowest quartile (few days and high amount); (3) low consumption of spirits – if the proportion of alcohol from spirits was lower than 25 %, participants received 1 point; (4) preference for wine – we scored 1 point if the proportion of alcohol derived from wine was at least 75 % of total alcohol intake; (5) consuming wine preferentially during meals – we scored 1 point if the proportion of alcohol from wine consumed with meals was at least 75 % of total alcohol from wine consumed; (6) preference for red wine over other types of wine – we scored 1 point if the proportion of red wine consumed is at least 75 % of total wine consumption; (7) avoidance of excess drinking occasions – we assigned 1 point if the maximum number of drinks consumed in a single weekday, or a day during the weekend, or in special occasions never exceeded five drinks.

Table 1 Score of the Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern

Q, quartile.

* Amount (g) of alcohol consumed per d from all types of beverages (red wine, other wines, beer and spirits).

† Quartiles of the ratio d/week of alcohol intake:g/week of alcohol consumed.

‡ Proportion of alcohol from spirits (g alcohol from spirits consumed/total g alcohol consumed).

§ Proportion of alcohol from wine (g alcohol from wine consumed/total g alcohol consumed).

∥ Proportion of wine consumed with meals (g alcohol from wine consumed with meals/g alcohol from wine consumed).

¶ Proportion of red wine over total wine (g alcohol from red wine consumed/g alcohol from wine consumed).

** Maximum drinks consumed in a single day during the weekend, during the week or in special occasions (during the past year).

We selected these cut-off points in order to better capture the traditional Mediterranean drinking pattern as described in previous publications( Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Bamia 14 – Reference Willett, Sacks and Trichopoulou 16 ), and also taking into account the shape of the dose–response curve observed in restricted cubic spline analyses for continuous variables.

Once these seven items are summed, the MADP score could potentially range from 0 to 9 points. We grouped participants into four categories according to this score: 0 to 2 points (low adherence); 3 to 4 (moderate–low); 5 to 6 (moderate–high); 7 to 9 (high adherence). Abstainers, who did not drink at all, were excluded from this computation, and they were classified in a fifth group.

Mortality assessment

Participants in the cohort study were carefully followed up in order to detect each death. At least annually, participants were contacted by mail and asked about changes of postal address. If postal mail failed, we used telephone or email contacts. We also exchanged information with the alumni associations and other professional associations to track participants. The closest relative, the appropriate professional association and the postal system allowed us to identify more than 85 % of deaths. For the rest of the deaths, we checked the National Death Index every 6 months to confirm the vital status of all our participants with no updated information. Death certificates and medical records of deceased participants were obtained. Causes of death were adjudicated, blinded to alcohol or dietary information, according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision( 17 ), and grouped as cardiovascular, cancer and other causes.

Covariate assessment

We gathered information about anthropometric, sociodemographic, lifestyle and medical variables from the baseline questionnaire. Physical activity was assessed through a validated questionnaire( Reference Martínez-González, López-Fontana and Varo 18 ). Adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern was evaluated using a well-known score( Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Bamia 14 ); however, we excluded alcohol intake to avoid overlapping with our main exposure.

Statistical analysis

To assess the relationship between adherence to the MADP and the risk of mortality, Cox regression models were fitted. Hazard ratios (HR) and their 95 % CI were calculated using the high-adherence group as the reference category. We also computed the HR for abstainers using this same category as the reference group. For the Cox regression model, age was the underlying time variable and exit time was defined as date of death or date when completing the last follow-up questionnaire (for survivors).

We also evaluated the risk of mortality associated with a 2-point increment in the MADP score, by introducing in the model the total score divided by 2 as a continuous variable. Tests for linear trend were also conducted. For these two latter analyses, abstainers were excluded.

First, age and sex were introduced in the model, and then, in the multiple-adjusted model, we additionally considered as potential confounders BMI (kg/m2), total energy intake (kJ/d), physical activity (metabolic equivalent task-h/week), prevalent or previous hypertension, prevalent hypercholesterolaemia, smoking habit (current smoker, former smoker or never smoker), tertiles of adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern, prevalent or previous cancer, presence of diabetes or CVD at baseline, and time spent watching television (h/week).

To assess the individual contribution of every specific MADP item, we fitted Cox regression models for each of the seven items using the highest score as the reference category. We evaluated the influence of each single item on mortality rates by alternately subtracting one single component from the overall MADP score, following the methodology of a previous article( Reference Trichopoulou, Bamia and Trichopoulos 19 ).

We conducted sensitivity analyses by rerunning all the models under different assumptions.

To compare the baseline characteristics of the participants according to the adherence to the MADP, we performed ANOVA (for continuous variables) and χ2 (for categorical variables) tests. Analyses were performed using STATA version 12.0 (StataCorp).

Results

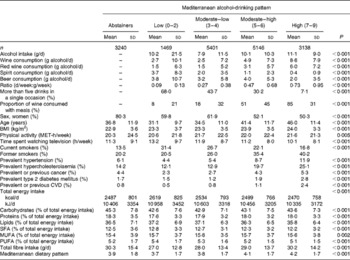

During the follow-up period (137 479 person-years), a total of 206 deaths were identified. The main characteristics of the 18 394 participants categorised according to their adherence to the MADP are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 Baseline characteristics according to the categories of the Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project 1999–2012 (Mean values and standard deviations or percentages)

MET, metabolic equivalent task.

Participants with a higher adherence to the MADP were older (46·0 years), less physically active, were less likely to be current smokers but more prone to be former smokers, and had better average adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern.

An inverse association between the MADP as a continuous variable and the risk of mortality was apparent (HR 0·75, 95 % CI 0·62, 0·89 for every 2-point increase in the MADP), with a significant inverse linear trend (P= 0·003).

As shown in Fig. 2, the inverse association between the MADP and the risk of mortality remained apparent within the categories of total alcohol intake, suggesting that additional reductions in mortality were associated with better adherence to the MADP beyond the effect of moderate alcohol intake.

Fig. 2 Hazard ratios for mortality according to the categories of the Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern (MADP) within each category of alcohol intake in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project 1999–2012. ![]() , Low MADP (0–2);

, Low MADP (0–2); ![]() , moderate MADP (3–6);

, moderate MADP (3–6); ![]() , high MADP (7–9). Adjusted for age, sex, BMI (kg/m2), total energy intake (kJ/d), physical activity (metabolic equivalent task-h/week), prevalent hypertension, prevalent hypercholesterolaemia, smoking habit (current smoker, former smoker or never smoker), Mediterranean dietary pattern (tertiles of adherence), prevalent or previous cancer, diabetes or CVD, and watching television (h/week).

, high MADP (7–9). Adjusted for age, sex, BMI (kg/m2), total energy intake (kJ/d), physical activity (metabolic equivalent task-h/week), prevalent hypertension, prevalent hypercholesterolaemia, smoking habit (current smoker, former smoker or never smoker), Mediterranean dietary pattern (tertiles of adherence), prevalent or previous cancer, diabetes or CVD, and watching television (h/week).

Moderate alcohol intake (5–25 g/d in women and 10–50 g/d in men) was inversely associated with all-cause mortality compared with abstainers in the present sample, but the CI included the null value (HR 0·69, 95 % CI 0·45, 1·06). However, beyond these results, adherence to the overall MADP in the highest level (7 to 9 points) showed a stronger reduction in the risk of mortality v. abstainers that was statistically significant (HR 0·55, 95 % CI 0·35, 0·88; P= 0·012).

When we used the highest category of adherence (7 to 9 points) to the MADP as the reference category, participants with a low adherence to the MADP (HR 3·09, 95 % CI 1·74, 5·50) and abstainers (HR 1·82, 95 % CI 1·14, 2·90) had a significantly higher risk of death than those with the highest adherence to the MADP, after adjustment for relevant confounders (Table 3). Participants with a moderate–low and moderate–high adherence also have a higher risk of death, but not statistically significant. Further adjustment for educational levels did not lead to any substantial change in these estimates.

Table 3 Mortality hazard ratios (HR) according to the categories of the Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern and for each additional 2-point increment in the score in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project 1999–2012 (Hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

* Adjusted for age, sex, BMI (kg/m2), total energy intake (kJ/d), physical activity (metabolic equivalent task-h/week), prevalent hypertension, prevalent hypercholesterolaemia, smoking habit (current smoker, former smoker or never smoker), Mediterranean dietary pattern (tertiles of adherence), prevalent or previous cancer, diabetes or CVD, and watching television (h/week).

The association between each single component of the MADP and the risk of mortality is presented in Table 4. After additional adjustment for all the other items, every MADP component was individually associated with a lower risk of death in its point estimate (data not shown), but usually the CI included the null value.

Table 4 Mortality hazard ratios (HR) for each component of the Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern, using the best score (only among drinkers) as the reference category, in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project 1999–2012 (Hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

* Abstainers were excluded.

† Low intake: < 5 g/d women; < 10 g/d men.

‡ Moderate intake: 5–25 g/d women; 10–50 g/d men.

§ High intake: >25 g/d women; >50 g/d men.

∥ Evenly distributed: fourth quartile of the ratio d/week of alcohol intake:g/week of alcohol consumed.

¶ Moderately distributed: third and second quartiles of the ratio d/week of alcohol intake:g/week of alcohol consumed.

** Not distributed: first quartile of the ratio d/week of alcohol intake:g/week of alcohol consumed.

†† Adjusted for age, sex, BMI (kg/m2), total energy intake (kJ/d), physical activity (metabolic equivalent task-h/week), prevalent hypertension, prevalent hypercholesterolaemia, smoking habit (current smoker, former smoker or never smoker), Mediterranean dietary pattern (tertiles of adherence), prevalent or previous cancer, diabetes or CVD, and watching television (h/week).

Every single component of the MADP seemed to have a similar influence on the inverse association with the risk of mortality, except for the total amount of alcohol consumed, the influence of which was slightly higher.

The main results of the present study were consistent for almost all the different scenarios that we included in the sensitivity analyses. For each additional 2-point increment in the MADP, we found stronger reductions for cardiovascular deaths (HR 0·55, 95 % CI 0·35, 0·84) than for cancer deaths (HR 0·86, 95 % CI 0·65, 1·13). To rule out the possible confounding effect of smoking habit, we reran the analysis only among never smokers, and we obtained the results in the same direction but without statistical significance due to the small number of deaths occurred among never smokers.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing an overall alcohol-drinking pattern to comprehensively account for different aspects of alcohol consumption beyond the total amount of alcohol intake. Consistent with previous studies( Reference Costanzo, di Castelnuovo and Donati 1 – Reference Di Castelnuovo, Costanzo and Bagnardi 3 ), we observed lower mortality among moderate drinkers. However, with our novel approach, we found that participants with a high adherence to a traditional Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern exhibited a 45 % relative reduction in overall mortality v. abstainers, well beyond the non-significant 31 % relative reduction observed when only moderate alcohol intake was taken into account. This finding suggests that the assessment of an overall drinking pattern is better than the simple appraisal of the total amount of alcohol intake to capture the potential effect of alcohol consumption on mortality. Other aspects of the drinking pattern beyond total intake are able to provide additional relevant information.

The additional information gained by including further dimensions of alcohol consumption seems biologically sound because blood alcohol concentration depends, among other factors, on the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption. Therefore, the same amount of total alcohol ingested will lead to higher blood alcohol concentration if it is consumed in a shorter period of time. Similarly, the same frequency of consumption will lead to higher blood alcohol concentration when the amount consumed in a single occasion is higher. Previous investigations have reported an increased risk of death for decreasing drinking-days( Reference Tolstrup, Jensen and Tjønneland 20 , Reference Baglietto, English and Hopper 21 ), or for the presence of heavy drinking occasions( Reference Rehm, Greenfield and Rogers 22 ), at the same level of alcohol consumption. Similar associations have been reported for myocardial infarction or major coronary events( Reference Mukamal, Conigrave and Mittleman 23 , Reference McElduff and Dobson 24 ). Also, higher concentrations of alcohol in the gastrointestinal tract may have a local carcinogenic effect and higher blood alcohol concentrations may promote pancreatitis and liver disease( Reference Wetterling, Veltrup and Driessen 25 ). These previous findings support the harmful effects of highly concentrated consumption patterns (binge drinking).

The type of beverage consumed is another important point. Although not all authors agree, moderate wine consumption has been associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular( Reference Renaud, Guéguen and Siest 26 – Reference Streppel, Ocké and Boshuizen 31 ), cancer( Reference Renaud, Guéguen and Siest 26 , Reference Klatsky, Friedman and Armstrong 28 , Reference Grønbaek, Becker and Johansen 29 ), external-cause( Reference Renaud, Guéguen and Siest 26 , Reference Klatsky, Friedman and Armstrong 28 ) and all-cause mortality( Reference Baglietto, English and Hopper 21 , Reference Renaud, Guéguen and Siest 26 – Reference Theobald, Bygren and Carstensen 30 , Reference Nielsen, Schnohr and Jensen 32 – Reference Strandberg, Strandberg and Salomaa 34 ), and with longer life expectancy( Reference Streppel, Ocké and Boshuizen 31 ) compared with beer or spirit consumption. Accordingly, we observed a lower rate of mortality among wine drinkers compared with non-wine drinkers. This protective benefit may be due in part to the quantity of alcohol consumed( Reference Vlachopoulos, Tsekoura and Tsiamis 35 , Reference Shai, Rimm and Schulze 36 ), but it can specially be strengthened by the presence of considerable amounts of polyphenols in wine( Reference Arranz, Chiva-Blanch and Valderas-Martinez 37 ). Moreover, wine consumption has previously been related to beneficial cardiovascular( Reference Kiviniemi, Saraste and Toikka 38 – Reference Pace-Asciak, Hahn and Diamandis 40 ) and anti-carcinogenic effects( Reference Jang, Cai and Udeani 41 , Reference Prescott, Grønbaek and Becker 42 ). An alternative explanation for this association is that wine drinkers are healthier than non-wine drinkers in other aspects( Reference Mortensen, Jensen and Sanders 43 ). For instance, dietary habits may differ from wine drinkers to beer drinkers or spirit drinkers. In order to account for confounding by these factors, several lifestyle variables, quality diet parameters and health indicators were included in the multiple-adjusted models. In addition, some of the associations found in previous studies may be due to different patterns of consumption among wine drinkers than in other drinkers. Actually, preference for wine drinking has been associated with a less concentrated pattern of consumption( Reference Grønbaek, Tjønneland and Johansen 44 ). Preferentially, wine drinkers are known to be at a lower risk of becoming heavy drinkers( Reference Jensen, Andersen and Sørensen 45 ). We found an inverse association between preference for wine and mortality, independently of other aspects of the alcohol-drinking pattern. On the contrary, preference for spirits did not show the same inverse association with the risk of mortality as wine. This differential effect also reported in a previous cohort study( Reference Streppel, Ocké and Boshuizen 31 ) could be explained because spirits are distilled beverages with higher concentrations of alcohol per unit, but with lower concentrations of polyphenols. Wine drinkers are also known to be at a lower risk of being involved in violent deaths than beer or spirit drinkers( Reference Norström 46 ). This difference can also contribute to their lower mortality rates.

Alcohol intake was derived from a FFQ. This questionnaire inquired about dietary habits during the past year. However, alcohol intake includes some variability across different times of consumption. Therefore, other additional aspects of alcohol consumption were inquired in the baseline questionnaire, including the maximum number of drinks consumed in a weekday, during the weekend or in special occasions during the past year, and the pattern of drinking wine during meals. Participants drinking more than five drinks in a single occasion were at a higher risk of mortality. This is consistent with previous findings( Reference Kauhanen, Kaplan and Goldberg 47 ), including also a recent research that found for binge drinkers a 14 to 168 % increased risk of all-cause death among men and a 26 to 106 % among women( Reference Graff-Iversen, Jansen and Hoff 48 ). Binge drinking has also been related to an increased risk of CHD and hypertension( Reference Murray, Connett and Tyas 49 ), and of mortality( Reference Mukamal, Maclure and Muller 50 , Reference Roerecke, Greenfield and Kerr 51 ). Other studies have reported a higher risk of death among heavy drinkers( Reference Rehm, Greenfield and Rogers 22 , Reference Malyutina, Bobak and Kurilovitch 52 – Reference Kauhanen, Kaplan and Goldberg 54 ), and these excess deaths are found to be especially attributable to cardiovascular and external causes( Reference Laatikainen, Manninen and Poikolainen 55 ). Heavy drinking occasions may trigger atherosclerosis( Reference Gruchow, Hoffmann and Anderson 56 , Reference Kiechl, Willeit and Rungger 57 ) and increase arrhythmias( Reference McKee and Britton 58 ), sexually transmitted disease( Reference Standerwick, Davies and Tucker 59 ), violence( Reference Brewer and Swahn 60 ) and traffic injuries.

Another important issue is the differential effect of consuming alcoholic beverages with meals or outside of meals. Some possible consequences of the consumption of alcohol with meals have been investigated: hypoglycaemic and insulin-lowering effects( Reference Hätönen, Virtamo and Eriksson 61 ); reduced postprandial blood pressure among hypertensive patients( Reference Foppa, Fuchs and Preissler 62 ); or a reduction in LDL susceptibility to lipid peroxidation( Reference Fuhrman, Lavy and Aviram 63 ). Only Trevisan et al. ( Reference Trevisan, Schisterman and Mennotti 64 ) reported an increased risk of cardiovascular, cancer and all-cause mortality (51 % increased risk) among drinkers outside of meals compared with drinkers of alcohol preferentially during meals, independently of the quantity of alcohol consumed. The present results are consistent with their findings.

Previous studies have frequently used the abstainers group as the reference category. However, artificially elevated rates of mortality in abstainers due to a higher mortality among former drinkers or to the avoidance of alcohol drinking because of medical causes (‘sick quitter’ hypothesis) may introduce some bias( Reference Shaper, Wannamethee and Walker 65 ). This was the reason why we did not use always the abstainers as the reference category. If another category is used as the reference, as we did in Tables 3 and 4, this potential bias will only affect the specific comparison for the abstainers group.

We did not adjust our analyses for socio-economic status. Participants in the SUN cohort study are all university graduates. Therefore, our sample is fairly homogeneous in this aspect, and this fact reduces the potential confounding by educational and socio-economic status. However, additional adjustment for educational levels did not substantially change the results.

Some degree of misclassification is possible in self-reported alcohol consumption and alcohol-drinking patterns. However, in the validation study of the FFQ( Reference Martin-Moreno, Boyle and Gorgojo 13 ), the correlation coefficient for alcohol (r 0·88) intake was higher than that for most other nutrients. Moreover, if there is some degree of misclassification, it will be more probably non-differential and therefore the association would be probably driven towards the null value.

The cut-off points for different items of the MADP intended to capture the concept of the traditional Mediterranean drinking pattern( Reference Heath, Grant and Litvak 10 , Reference Renaud and de Lorgeril 15 , Reference Willett, Sacks and Trichopoulou 16 ). However, some of these cut-off points may be debatable and some degree of arbitrariness needs to be acknowledged as a limitation. In spite of that, the results of some sensitivity analyses after changing the cut-off points for different items showed the robustness of the association between the MADP score and total mortality.

Some items of the MADP could potentially exhibit collinearity. However, in our database, we observed κ coefficients for every two items ranging from − 0·103 to +0·31. Therefore, collinearity seems not to be a very relevant issue. Moreover, collinearity could be used to advantage because patterns are characterised on the basis of a comprehensive assessment of related behaviours( Reference Hu 66 ).

Studies investigating one single aspect of alcohol consumption have some limitations: they may be confounded either by other aspects or by the whole pattern; the effect of a single aspect could be small and not detectable; the correlation between aspects makes it difficult to assess them separately( Reference Schulze and Hoffmann 67 ). Therefore, since drinking alcohol involves more dimensions than the specific amount of alcohol consumed, the best way to fully appraise the association between alcohol-drinking choices and health is to adopt the dietary pattern approach. This is currently the customary and accepted approach in other fields of nutritional epidemiology because this comprehensive approach allows for synergies and interactions, pre-empts confounding by other aspects of the pattern, gets closer to the real world and gives a more practical basis to issue public health recommendations( Reference Hu 66 ).

The limits for alcohol intake that we proposed might be seen as apparently high compared with some current guidelines. However, these guidelines usually do not take into account the role of the whole pattern of alcohol consumption.

In summary, the consumption of alcohol following a pattern of consumption that gets away from the traditional Mediterranean drinking habits is associated with a higher risk of mortality, as it is the total abstention of alcohol in comparison with good conformity to the traditional Mediterranean drinking pattern. Notwithstanding this result, perhaps the most sensible conclusion is that abstainers should not be counselled to start drinking because if they do it in a wrong way they may adopt drinking patterns with the potential to increase their risk of death. It is worth not to forget that alcohol intake is the eighth global death risk factor and the third risk factor for disease and disability measured in disability-adjusted life years( 68 ). However, if a person goes for drinking, the Mediterranean drinking pattern can be considered a sensible and healthy way of consuming alcohol.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the participants of the SUN Project for their continued cooperation and participation. We thank other members of the SUN Group: A. Alonso, F. J. Basterra-Gortari, S. Benito, J. de Irala, C. de la Fuente-Arrillaga, M. Delgado-Rodríguez, F. Guillén-Grima, J. Krafka, J. Llorca, C. López del Burgo, A. Marti, J. A. Martínez, J. M. Nuñez-Córdoba, A. M. Pimenta, M. Ruiz-Canela, D. Sánchez, C. Sayón-Orea, M. Seguí-Gómez, M. Serrano-Martínez and Z. Vázquez.

The present study, as part of the SUN Project, was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI01/0619, PI030678, PI040233, PI042241, PI050976, PI070240, PI070312, PI081943, PI080819, PI1002658, PI1002293, PI1300615, RD06/0045, 2010/087, G03/140 and Rio Hortega CM10/00072 to E. T.), the Navarra Regional Government (36/2001, 43/2002, 41/2005, 45/2011 and 36/2008), the University of Navarra (PIUNA 9923), CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERObn), Instituto de Salud Carlos III and Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (A. G., FPU). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

The authors' contributions are as follows: A. G. conducted the literature review, participated in the design of the present study, cleaned the data, conducted the main statistical analyses and prepared the first draft of the manuscript; M. B.-R., E. T., M. G.-L., J. J. B., R. E. and M. A. M.-G. participated in the statistical analysis plan and in the design of the present study, revised the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the findings; M. A. M.-G., being the guarantor, supervised all the steps in the statistical analyses and preparation of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

R. E. reports serving on the board of and receiving lecture fees from the Research Foundation on Wine and Nutrition (FIVIN), serving on the boards of the Beer and Health Foundation and the European Foundation for Alcohol Research (ERAB), receiving lecture fees from Cerveceros de España and Sanofi-Aventis, and receiving grant support through his institution from Novartis, outside the submitted work. None of the other authors has any conflict of interest.