Introduction

The hog deer Axis porcinus formerly occurred from Pakistan and northern India eastwards through Nepal and Bhutan to Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia and Viet Nam (Timmins et al., Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2015), and was marginally distributed in Yunnan, China. The hog deer is listed as a National Category I Key Protected Wild Animal Species in China, categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Timmins et al., Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2015) and as Critically Endangered on China's Red List of Biodiversity because of its narrow range and small population size (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Jiang, Wang, Zhang, Zhang and Li2016a).

The number of hog deer populations in South-east Asia declined by > 90% from 1991 to 2012, and the species is extinct in Thailand, Lao PDR and Viet Nam, but has been reintroduced in Thailand and Pakistan (Timmins et al., Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2012, Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2015). In China, the hog deer was formerly recorded in Gengma and Cangyuan Counties, in the Nanting River watershed, south-west Yunnan, bordering Myanmar (Yang & Ma, Reference Yang and Ma1965; Wang et al., Reference Wang1998). Hog deer were first reported in China in 1962, with > 10 individuals in Sifangjing village, Gengma County (Yang & Ma, Reference Yang and Ma1965). The number of individuals in Cangyuan Country at that time is unknown. Since 1965, the hog deer has not been recorded, and it was presumed to have been extirpated (Smith & Xie, Reference Smith and Xie2009), although interviews and field surveys indicated that a small population may survive in Daxueshan and Nangunhe Nature Reserves (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Wang and Yan2007; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Du and Sun2015). In 2007 a fawn initially identified as a hog deer was rescued by forest rangers in Daxueshan Nature Reserve, but it was later confirmed to be a calf of sambar Rusa unicolor (Timmins et al., Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2012, Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2015).

The hog deer lives in floodplain grasslands and tends to avoid dense forests and cultivated areas (Dhungel & O'Gara, Reference Dhungel and O'Gara1991; Bhowmik et al., Reference Bhowmik, Chakraborty and Raha1999; Biswas & Mathur, Reference Biswas and Mathur2000; Odden & Wegge, Reference Odden and Wegge2007). Compared to the sympatric sambar, the hog deer has more specialized habitat requirements (Johnsingh et al., Reference Johnsingh, Qureshi, Goyal, Rawat, Ramesh and David2004; Wilson & Mittermeier, Reference Wison and Mittermeier2011), and may be more sensitive and vulnerable to the threats of habitat loss and degradation (Wilson & Mittermeier, Reference Wison and Mittermeier2011). The hog deer has disappeared from large parts of its original range as a result of hunting pressure and conversion of floodplain grassland for agriculture (Timmins et al., Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2015).

Assessing a species’ status and any threats is the basis for implementing a conservation plan (Margules & Pressey, Reference Margules and Pressey2000). As the hog deer has not been formally recorded in China since 1965, we conducted interviews, and transect and camera-trap surveys to determine whether the species is still present within its former range in the country.

Study area

Our study area covers Cangyuan, Gengma, Yongde and Zhenkang Counties in Lincang City, Yunnan Province, China, bordering Myanmar in the south-west (Fig. 1). Lincang City has a subtropical mountain monsoon climate with distinct dry and rainy seasons, mean annual temperature is 17.3 °C and total annual rainfall is 920–1,750 mm. The Nanting River runs through the area from north-east to south-west. The city is known for cultivation of macadamia (Macadamia spp.), with c. 175,000 ha of plantation accounting for > 50% of global production (Chen, Reference Chen2017); rubber trees and tea are also cultivated extensively.

Fig. 1 The study area of Yongde, Gengma, Cangyuan and Zhenkang counties in Lincang City, Yunnan Province, China, showing the sites where we interviewed people and carried out the transect and camera-trap surveys.

The Nangunhe Nature Reserve lies in Cangyuan and Gengma Counties and is one of China's priority conservation areas, established in 1980, upgraded to a National Nature Reserve in 1995 and extended from 71 to 508 km2 in 2003. We focused on the core zone of the Reserve as hog deer have never been recorded in the buffer and experimental zones where the montane terrain is not typical habitat for hog deer. The altitudinal range of the core zone is 460–1,750 m and vegetation comprises broadleaf evergreen forest, tropical rainforest, shrubland and grassland.

Daxueshan Nature Reserve lies in eastern Yongde County, in the southern extension of the Nujiang Mountains, which is the watershed between the Lancang and Nujiang Rivers. The 175 km2 Reserve lies at altitudes of 960–3,504 m and vegetation ranges from tropical seasonal rainforest to temperate alpine forest.

Methods

We firstly reviewed available literature to confirm the historical range of the hog deer, and examined a high-resolution topographic map of potential hog deer habitat, including Nangunhe and Daxueshan Nature Reserves, which are the most likely sites of any surviving hog deer in China (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Wang and Yan2007; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Du and Sun2015).

We interviewed 50 local residents during the survey (Table 1), including villagers, forest rangers, hunters and other researchers in the region. These interviews were conducted in 16 villages in four counties across the historical distribution range of hog deer (Fig. 1), during October–November 2018 and June–July 2019. We surveyed the Nanting River watershed from north-east to south-west, including Daxueshan Nature Reserve and the surrounding area, Sifangjiang village and Mengding Farm in Gengma County, Nangunhe Nature Reserve in Cangyuan County and Nanpenghe Nature Reserve in Zhenkang County. We asked interviewees to describe the physical characteristics of any deer they saw, such as body size and antlers, and then we showed photographs and illustrations of the hog deer and sambar (Smith & Xie, Reference Smith and Xie2009) to ask them to distinguish and identify the species. Next, we inquired about (1) the current and historical presence of hog deer, (2) the number of hog deer and sites where they had been seen, (3) the number of years since the species had last been sighted, and (4) the number of hog deer hunted recently or historically in the area. The data were considered to be valid only if they were provided by people who were knowledgeable about the species and could clearly describe the characteristics that facilitate discrimination of the two species (Quiroga et al., Reference Quiroga, Boaglio, Noss and Di Bitetti2013).

Table 1 Details of survey sites and survey effort for hog deer Axis porcinus during 2018–2020 in Yunnan, China (Fig. 1), with dates of surveys, number of interviewees in and around sites, total length of transect surveys for signs, number of camera traps (each with a single camera), mean distance between camera-trap stations, and minimum convex polygon covered by camera traps.

We drove slowly along the Nanting River, occasionally stopping to survey the environment on both sides of the river to evaluate the potential suitability of the habitat for hog deer. Similarly, we investigated the environmental conditions in Sifangjing village and Mengding Farm. After preliminary surveys along the Nanting River, we established six line transects (2.9–10.8 km long) and 82 camera stations in Daxueshan Nature Reserve along an elevational range of 900–2,630 m, six line transects (4.9–12.3 km) and 68 camera stations in Nangunhe Nature Reserve along an altitudinal gradient of 460–1,100 m (Table 1) from October 2018 to June 2020, and one line transect of 10.8 km in Mending Farm. We walked each transect twice to search for signs of the hog deer. The cameras (Ereagle E1B, Prestar Technology, Beijing, China) were set singly on animal trails along the transects in Daxueshan and Nangunhe Nature Reserves (we did not install camera traps in Mengding Farm because of the high intensity of agriculture and other human activities there), fixed to tree trunks c. 1 m above the ground, and operated continuously, with a 10-s delay between sequential triggers. We chose this height to avoid interference from grass growth, and we angled the cameras downwards to ensure that small species could be trapped. Cameras were placed preferentially in floodplain grasslands, to increase the probability of detecting the hog deer (92 and 58 camera stations were placed in grassland and forest, respectively). Cameras were visited every 2 months, by Reserve staff, to replace batteries or to download images.

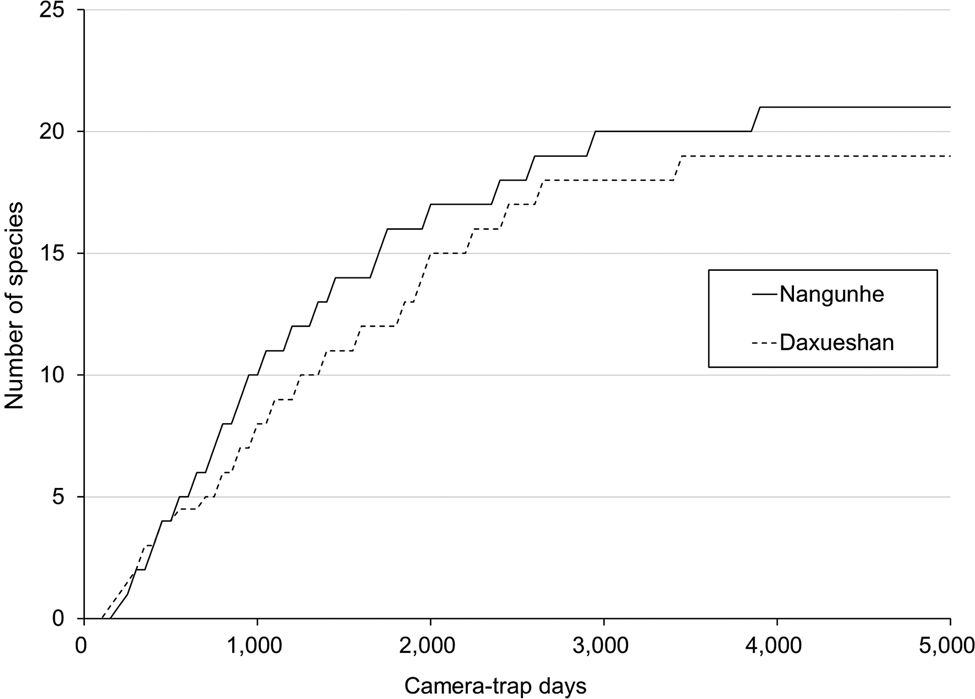

For each camera, we recorded the time of monitoring, the total number of photographs, number of photographs of animals, number of species, and number of notionally independent photographs. We defined independent photographs as (1) photographs of different individuals of the same or different species, (2) photographs of individuals of the same species captured at least 30 minutes apart, or (3) non-consecutive photographs of individuals of the same species (Azlan, Reference Azlan2006; Foster & Harmsen, Reference Foster and Harmsen2012). We calculated the capture frequency of a given species as the number of independent photographs/1,000 camera days (Tobler et al., Reference Tobler, Carrillo-Percastegui, Pitman, Mares and Powell2008a). Sampling effort was measured as the product of the total number of stations and the number of effective days of sampling. A species accumulation curve of the number of species recorded as a function of cumulative camera days was used to determine the adequacy of the sampling period (Ugland et al., Reference Ugland, Gray and Ellingsen2003).

To assess the potential habitat for hog deer along the Nanting River, we created a 1-km wide buffer zone along each side of the river in ArcGIS 10.2 (Esri, Redland, USA), with the size of the buffer based on the fact that hog deer live in small, overlapping home ranges of 0.11–2.23 km2 (Dhungel & O'Gara, Reference Dhungel and O'Gara1991; Odden & Wegge, Reference Odden and Wegge2007). We then used 30-m resolution land cover data (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Zhu, Yuan, Suen and Guo2019) to perform spatial overlay analysis to extract land cover types within the buffer zone.

Results

Forty-two of the 50 people interviewed said they had seen or heard hog deer in the 1960s–1980s. Twenty-eight of the interviewees said they had not seen hog deer or its signs since the early 1980s, and five indicated that the last known occurrence of hog deer was during 2007–2016, but we found they could not distinguish hog deer from juvenile sambar. Two experienced older hunters in Mengding town said the hog deer was formerly a common species in the floodplain grasslands of the Nanting River and was hunted for meat in the 1960s, but had disappeared from the area with the development of the 80 km2 Mengding Farm. From our transect survey, we conclude that Mengding Farm and the surrounding area is no longer suitable for hog deer because of the high intensity of agricultural development and associated human activities. We also inspected a 0.028 km2 micro-reserve for the preservation of the ironwood Mesua ferrea, designated by Sifangjing village, but found there was no suitable habitat there for hog deer. In neither the transects surveys nor the interviews were we able to confirm that the hog deer survives in this region.

We obtained 3,248 notionally independent photographs of 21 species of mammals (Table 2) in a total of 15,120 camera days in Nangunhe Nature Reserve, and 3,369 independent photographs of 19 mammal species in 13,554 camera days in Daxueshan Nature Reserve. The species accumulation curve for Nangunhe Nature Reserve and Daxueshan Nature Reserve approached an asymptote at c. 4,000 and 3,500 camera days, respectively (Fig. 2). The sambar, Indian muntjac Muntiacus muntjak and wild boar Sus scrofa were the three most common species captured by the cameras. Asian elephant Elephas maximus, leopard Panthera pardus, dhole Cuon alpinus and Phayre's leaf monkey Trachypithecus phayrei were also recorded but we did not detect hog deer at any of the sites.

Table 2 Mammal species camera-trapped in the core zone of Nangunhe and Daxueshan Nature Reserves (not including photographs of shrews, small squirrels and rats, which could not be positively identified), by order, with the number of independent photographs per 1,000 camera-trap days.

1 This record is outside the range of this species indicated on the IUCN Red List (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Zhou, Zhang, Savolainen and Wang2016; Boitani et al., Reference Boitani, Phillips and Jhala2018).

In the Nanting River buffer zone, grassland covered an area of c. 122 km2 (Fig. 3), accounting for 14% of riparian land. Forest and cropland were the main landscape types in this area. Phragmites australis and Microstegium vagans, typical riparian grassland species, were only sporadically interspersed within the matrix of croplands and settlements, and are probably insufficient to support a viable population of hog deer.

Fig. 3 The area of the various land cover types within a 1-km wide buffer zone along each side of the Nanting River.

Discussion

Despite using three techniques (interviews, and transect and camera-trap surveys), we were unable to find evidence that the hog deer is extant in China. Most of the interviewees indicated they had not seen the species since the 1980s. It appears likely that the large-scale destruction of floodplain grasslands in the 1960s and 1970s caused the initial decline of the hog deer, and subsequent uncontrolled hunting resulted in its extirpation.

To detect rare species, a large number of camera-trap sites and extended surveys are required (Cheyne & MacDonald, Reference Cheyne and MacDonald2011; Burton et al., Reference Burton, Neilson, Moreira, Ladle, Steenweg and Fisher2015), and > 3,000 camera-trap days are recommended (Tobler et al., Reference Tobler, Carrillo-Percastegui, Pitman, Mares and Powell2008a,Reference Tobler, Carrillo-Percastegui, Leite Pitman, Mares and Powellb; Si et al., Reference Si, Kays and Ding2014). Our two surveys both had > 3,000 camera-trap days and the sampling saturation was high, and we therefore conclude that the probability that the hog deer occurs but remained undetected by us is almost zero.

In Nangunhe Nature Reserve the forest and grassland have been replaced by farmland and plantations (Grueter et al., Reference Grueter, Jiang, Konrad, Fan, Guan and Geissmann2009). The Wa people living on both sides of the China/Myanmar border were formerly hunters. Although hunting is now banned, the Reserve is still subject to pressures from shifting cultivation. We found that livestock grazing was prevalent in Nangunhe, and domestic buffalo and cattle were recorded by all of our camera traps. We detected poaching in Daxueshan Nature Reserve, with armed hunters recorded five times, and seven cameras were stolen or destroyed. The majority of tall floodplain grasslands along the Nanting River were lost in the mid to late 1970s with the establishment of Mengding Farm (Wang, Reference Wang1998), and only small patches of reeds remain.

The hog deer is an obligate grassland species that rarely uses closed evergreen forest (Johnsingh et al., Reference Johnsingh, Qureshi, Goyal, Rawat, Ramesh and David2004; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Nareth, Kong, Timmins and Duckworth2007). Given this habitat specificity, hog deer appear to be unable to survive when riparian grasslands are converted to other uses, whereas the sambar, being a generalist species, can survive in a range of habitats (Clavel et al., Reference Clavel, Julliard and Devictor2011) and can shift its range to higher altitudes (Jotikapukkana et al., Reference Jotikapukkana, Berg and Pattanavibool2010). Conservation priority should be given to species with high ecological vulnerability when they are exposed to intense pressure from human activities (Johnson, Reference Johnson1998; Cardillo et al., Reference Cardillo, Mace, Jones, Bielby, Bininda-Emonds and Sechrest2005).

The south-west margin of China is located in the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot (Mittermeier et al., Reference Mittermeier, Myers, Thomsen, Da Fonseca and Olivieri1998), where the typical large mammal species are of the tropical and subtropical fauna of South-east Asia, such as the Asian elephant, Indo-Chinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti, gibbons (Hylobatidae), gaur Bos gaurus, banteng Bos javanicus, Asian buffalo Bubalus arnee, mouse deer Tragulus williamsoni, hog deer and the Rhinocerotidae (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, Rhinoceros sondaicus and Rhinoceros unicornis), the latter extinct in China (Wen et al., Reference Wen, He and Gao1981; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li, Luo, Tang, Li and Hu2016b). All of these species are threatened by habitat loss and overexploitation, and there is a lack of coordinated measures for their conservation (Wison & Mittermeier, Reference Wison and Mittermeier2011; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li, Luo, Tang, Li and Hu2016b; Ding et al., Reference Ding, Hu, Li and Jiang2018). The Chinese government is, however, collaborating with the governments of Lao PDR, Myanmar and Viet Nam to establish a transboundary conservation region. Coordinated conservation measures between countries could contribute to the integrity of species and habitats (Kark et al., Reference Kark, Tulloch, Gordon, Mazor, Bunnefeld and Levin2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yong, Choi and Gibson2020).

Our results indicate that the hog deer is probably extirpated from China. There is little chance of natural recolonization by the species from neighbouring countries without habitat restoration and protection, and poaching control. The hog deer marginally distributed in China is regarded as Axis porcinus annamiticus (Wison & Mittermeier, Reference Wison and Mittermeier2011), the subspecies also occurring in Thailand and Cambodia, and formerly in Lao PDR and Viet Nam (Timmins et al., Reference Timmins, Duckworth, Samba Kumar, Anwarul Islam, Sagar Baral, Long and Maxwell2015). The native population is small in Cambodia (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Nareth, Kong, Timmins and Duckworth2007; Brook et al., Reference Brook, Chanta and Phan2015). To restore the hog deer in China and to promote the wider conservation of the species, we recommend establishment of a protected area in the Nanting River watershed. Within this area, habitat restoration and reintroduction are priorities for the hog deer. Wetlands, especially floodplain grasslands, often receive insufficient protection, and a reintroduced hog deer population could be a flagship for reversion of some of the agricultural lands of the Nanting River watershed to floodplain grasslands.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Second National Terrestrial Vertebrate Survey, China State Forest and Grassland Administration, and the National Key Research & Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC0503303, No. 2016YFC0503304), and the Biodiversity Survey and Assessment Project of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China (No. 2019HB2096001006). We thank two reviewers for their comments and suggestions; Xiaoge Ping, Dandan Cao, Yaxin Liu and Hongxia Fang for help with fieldwork; and staff members and forest rangers from Nangunhe and Daxueshan Nature Reserves for their support and help.

Author contributions

Study design: ZJ, CD, CL; data collection and analysis, writing: CD, JL; fieldwork, revision: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Our investigations were approved by the China State Forest and Grassland Administration and Yunnan Forestry and Grassland Administration, interviews were permitted by the Authority of Daxueshan and Nangunhe Nature Reserves, and this research otherwise abided the by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.