Introduction

Legal rights may appear powerful, but their impact is often mediated and constrained by the very organizations they seek to regulate. This limitation is evident in both domestic and transnational contexts. In domestic settings, scholars of law and organizations have highlighted the restricted influence of equal employment rights under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, showing how legal interpretation became dominated by managerial personnel within regulated organizations (Dobbin and Kalev Reference Dobbin and Kalev2021; Dobbin and Kelly Reference Frank and Kelly2007; Edelman Reference Edelman1992; Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Fuller and Mara‐Drita2001, Reference Edelman, Uggen and Erlanger1999; Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey Reference Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey2012). At the transnational level, legal rights tend to be even weaker due to the frequent absence of effective enforcement mechanisms. Research shows that states often commit to international human rights law to gain legitimacy on the global stage while avoiding substantive behavioral changes. Many states continue to engage in practices such as torture, forced disappearances, or political imprisonment, even after ratifying treaties that explicitly prohibit them (Hafner-Burton and Ron Reference Hafner-Burton, James, Abouharb, Cingranelli, Bob, Cardenas, Hertel, Hopgood, Landman, Merry and Rejali2009; Hafner‐Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005; Hathaway Reference Hathaway2002).

The relationship between formal legal commitments and actual practices is frequently analyzed through the lens of “coupling,” a concept drawn from neoinstitutional theory in organizational sociology. Rights ineffectiveness is often attributed to “loose coupling,” where organizations adopt legal commitments to enhance legitimacy but loosely couple their practices to minimize disruption to existing routines (Hafner‐Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005; Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977). However, loose coupling can also be “tightened” when strong internal or external pressure drives compliance (see Hallett and Ventresca Reference Tim and Ventresca2006; Sauder and Espeland Reference Sauder and Espeland2009). This potential for tight coupling is well-documented in the legal mobilization literature (Barnes and Burke Reference Jeb and Burke2012; Lejeune Reference Lejeune2017; McCann Reference McCann1994). In the realm of human rights, the most crucial pressure typically comes from civil society, including international watchdog organizations and domestic social movements (Simmons Reference Simmons2009; Thomas and Ropp Reference Thomas, Ropp, Sikkink, Ropp and Risse2013; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Ropp and Sikkink1999). Other key stakeholders – such as policymakers (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2021; Grugel and Peruzzotti Reference Grugel and Peruzzotti2012; Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014), state bureaucrats (Paschel Reference Paschel2016; R. Martin Reference Martin2021), and domestic courts (Lake Reference Lake2018; Lupu et al. Reference Lupu, Verdier and Versteeg2019) – can also serve as allies to rights advocates, helping to strengthen the alignment between treaty ratification and state practices.

However, the binary of loose versus tight coupling overlooks a common yet underexamined reality: organizational practices often lead to partial fulfillment of legal commitments that fits neither category. Moreover, this state tends to persist, rather than serving as a transitional phase between loose and tight coupling. For instance, in the United States, the organizational mediation of civil rights law has endured for decades. While scholars continue to debate the extent of its substantive impact, they agree that these changes are not merely symbolic nor comprehensive (see Dobbin and Kalev Reference Dobbin, Kalev, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017; Edelman Reference Edelman2016; Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey Reference Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey2012). Assessing the effects of human rights presents similar complexities. Rights with strong international recognition, such as protections against torture, have been widely adopted and incorporated into legal frameworks. However, their institutionalization often stalls unexpectedly in postconflict societies and occasionally regresses even in well-established democracies (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2021; Shor Reference Shor2008; Sikkink Reference Sikkink2013). How can we make sense of this liminality in rights implementation? And how does it relate to contention within the very organizations the law seeks to regulate?

This article introduces the concept of contentious coupling to explain why legal rights produce substantive but constrained effects on organizational practices. I illustrate this framework through the case of human rights law’s influence on solitary confinement reform in Taiwan, a young democracy often regarded as an exemplar in implementing international human rights (see Chen Reference Chen2020; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Alford and Lo2019). While Taiwan’s implementation of prisoners’ rights against solitary confinement has been substantive, thanks to a strong coalition between rights advocates and policymakers, it remains constrained by passive resistance from frontline correctional officers. Paradoxically, both the progress and limitations of these reforms stem from the same process: hierarchical enforcement within a demanding work environment. While enforcement ensures compliance among frontline officers, it also alienates many by triggering feelings of relative deprivation and perceptions of hypocrisy, even among those who do not oppose restrictions on solitary confinement per se. This alienation is reflected in officers’ complaints about a “human rights upsurge,” a phrase expressing their belief that prisoners’ rights have expanded excessively. In response, they engage in two forms of passive resistance – formalistic care and resistance spillover – which undermine the authority of human rights and hinder their institutionalization within correctional culture.

The concept of contentious coupling makes three key contributions to the study of human rights and law and organizations. First, it highlights a common pattern in which human rights produce substantive yet ultimately constrained changes to state practices. Under such conditions, improving human rights protections requires addressing the relational sources of resistance among state actors – in this case, the exploitative conditions faced by frontline correctional officers – rather than simply enhancing the dissemination and enforcement of rights. Second, by conceptualizing the state as an organization, contentious coupling advances law and organizations scholarship by demonstrating that intraorganizational contention is central to how legal norms shape organizational practices, which may, in turn, influence the institutionalization of these norms as endogenous law (Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Uggen and Erlanger1999). Lastly, contentious coupling resonates with punishment scholars’ call to “fracture the penal state” (Rubin and Phelps Reference Rubin and Phelps2017), illustrating how penal reforms emerge from multi-actor conflicts that transcend a simple liberal–conservative binary. The case of Taiwan further demonstrates how international human rights complicate these struggles, introducing both new opportunities and challenges to penal reforms.

Contentious coupling during organizational mediation of rights

Loose coupling in civil rights and human rights studies

Neoinstitutional analysis offers a valuable framework for understanding how legal rights shape organizational practices. Traditional neoinstitutionalism argues that organizations constantly navigate a tension in a rationalized world. On one hand, they must pursue their technical goals efficiently. On the other hand, they must demonstrate alignment with widely recognized norms and expectations within their institutional environment or the “organizational field,” a network of organizations that collectively shape a specific domain of institutional activity, to maintain legitimacy (Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977, 343–44; DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983, 148; see also Hallett Reference Hallett2010; Rubin et al. Reference Rubin, Vaughn and Rudes2024).Footnote 1 To manage this tension, organizations adopt formal policies or structures to signal commitment to these norms while loosely coupling them with actual practices, thereby buffering technical goals from substantive change. Once these formal policies or structures become institutionalized within the organizational field, they serve as symbols of compliance, even when they are largely disconnected from day-to-day operations.

Building on this insight, law and society scholars have demonstrated how organizations adopt formal policies to signal legal compliance while making only limited changes to their practices. For instance, in response to equal employment rights under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, organizations established compliance offices, training programs, and grievance procedures aimed at eliminating workplace discrimination. However, while these formal policies have had limited effects in curbing discriminatory practices, they have been recognized by courts as evidence of compliance, serving as a powerful defense against litigation (Dobbin and Kelly Reference Frank and Kelly2007; Edelman Reference Edelman1992; Reference Edelman2016; Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Uggen and Erlanger1999; Kalev and Dobbin Reference Kalev and Dobbin2006; Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey Reference Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey2012). Similar patterns have been observed in other domains, including prisoners’ rights (Calavita and Jenness Reference Calavita and Jenness2015; Jenness and Smyth Reference Jenness and Smyth2011), consumer rights (Kameo Reference Kameo2015; Talesh Reference Talesh2009), and environment protection (Short and Toffel Reference Short and Toffel2010), where ceremonial procedures substitute for substantive rights implementation. While these procedures do not necessarily nullify legal protections, they create significant gaps between organizational commitments and actual practices.

In the realm of international human rights, the problem of loose coupling is even more pronounced. The world society literature argues that the pursuit of legitimacy compels states to commit to human rights and other global norms, such as environmental protection and anti-corruption measures, without necessarily fulfilling those commitments (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997, 164–65; see also Boyle and Meyer Reference Boyle and Meyer1998; Frank et al. Reference Frank, Hardinge and Wosick-Correa2009; Strang and Meyer Reference David and Meyer1993). The ambiguity of human rights law, combined with weak enforcement mechanisms, further incentivizes loose coupling (see Edelman Reference Edelman1992). Research has shown that while ratifying human rights treaties often leads to the adoption of relevant policies or legislation, it has limited effects on reducing rights violations and may primarily serve to legitimize ruling regimes (Cronin-Furman Reference Cronin-Furman2020; Englund Reference Englund2006; Long Reference Long2018; Zhang and Buzan Reference Zhang and Buzan2020). In some cases, treaty ratification is even correlated with worsened human rights protections (Cole Reference Cole2005; Hafner‐Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005; Hathaway Reference Hathaway2002).

Tight coupling and its sources

The loose coupling between formal policies and practices can, however, be “tightened” under pressure to comply more substantially with institutionalized norms. Tight coupling may result from external coercion within the organizational field (see DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) or from internal actors who view loose coupling as problematic. Drawing on Foucault’s insights on discipline, Sauder and Espeland (Reference Sauder and Espeland2009, 65) find that ranking policies in law schools tend to be tightly coupled with practices because faculty members, motivated by anxiety or material and symbolic rewards, internalize the need for compliance. Adopting an interactionist perspective that highlights intraorganizational conflicts, Hallett (Reference Hallett2010) further argues that tight coupling can emerge when powerful organizational members compel the less powerful to comply. His fieldwork in an elementary school shows that accountability standards, previously only loosely coupled with practices, were enforced by a new administrator who strongly identified with them. This reform not only successfully tightened coupling but also caused “turmoil” among staff who scrambled to adjust their performance.

Tight coupling in human rights studies is rare, but scholars have identified domestic contention as a key mechanism driving it. While earlier studies overwhelmingly demonstrate loose coupling between human rights commitments and practices (Hafner-Burton and James Reference Hafner-Burton, James, Abouharb, Cingranelli, Bob, Cardenas, Hertel, Hopgood, Landman, Merry and Rejali2009; Hafner‐Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005; Hathaway Reference Hathaway2002), recent research paints a more optimistic picture (Fariss Reference Fariss2019; Sikkink Reference Sikkink2017; Simmons Reference Simmons2009; Tsutsui Reference Tsutsui2018; Cole Reference Cole2012). Essentially, human rights commitments are more closely coupled with practices when robust human rights advocacy coincides with support from state actors. Using two-stage least squares models, Simmons (Reference Simmons2009) demonstrates that ratification of human rights treaties provides domestic advocacy with leverage to improve rights protections, particularly in democratizing regimes where both incentives and opportunities for reform exist. Hillebrecht (Reference Hillebrecht2014, 87–93) provides an example of this dynamic, showing how Argentina’s administration leveraged rulings from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the early 2000s to implement critical reforms, including repealing amnesty laws and disbanding military courts (see also Hillebrecht and Huneeus Reference Hillebrecht and Huneeus2018; Jung Reference Jung2024; Meyers Reference Meyers2019b; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000; Sikkink Reference Sikkink2011; Thomas and Ropp Reference Thomas, Ropp, Sikkink, Ropp and Risse2013).

More recently, however, human rights scholars have found that divisions within the state complicate the path to tight coupling. State actors do not always agree on whether or how to comply with human rights law, and their internal conflicts create space for human rights to have some, though limited, effects. Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2021) reports that while some Senegalese political elites support LGBT rights within a “pocket of world society,” they lack the broader political backing needed to override domestic legal authorities who see themselves as upholding public sentiment through the prosecution of homosexuality. Accordingly, these political elites can only promote sexual rights rhetorically while working behind the scenes to curb legal enforcement. As Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2021, 718) concludes, “adherence and resistance to world culture is not only (or primarily) a story of what happens between states, but one that unfolds within states and between different agencies at different levels.” This insight – that conflicts among state actors can constrain human rights compliance – echoes findings from other studies, though not always within a neoinstitutional framework (Grugel and Peruzzotti Reference Grugel and Peruzzotti2012; Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2012; R. Martin Reference Martin2021; T. M. Martin; Reference Martin2017; Paschel Reference Paschel, Kimberly and Orloff2017). These studies suggest that efforts to strengthen coupling may grant human rights a “prescriptive status” within the well-known spiral model (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Ropp and Sikkink2013) and generate substantive reforms. However, progress is often modest, prone to stalling, or even vulnerable to backsliding, failing to establish stable, rule-consistent behaviors (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2021; Sandra et al. Reference Sandra, Brinks and Gonzalez-Ocantos2022; Shor Reference Shor2008).

The mixed outcomes of human rights mobilization suggest that neither loose nor tight coupling fully captures how human rights are implemented in practice. Given the heterogeneity among state actors, it is unsurprising that these dynamics are more complex than the loose–tight binary that much of the existing literature relies on. Some studies have proposed alternative conceptual frameworks. Bromley and Powell (Reference Patricia and Powell2012) argue that loose coupling can exist not only between commitments and practices but also between the means and ends of fulfilling those commitments. This perspective suggests that institutionalized norms can have substantive effects even when constrained. While insightful, it largely overlooks the role of intraorganizational contention in shaping these processes. By contrast, Bartley and Egels-Zandén (Reference Bartley and Egels-Zandén2016) introduce the concept of “contingent coupling” to describe the contentious, circumstantial realignment of organizational commitments and practices. Their study finds that union activists in Indonesian apparel and footwear factories occasionally compel employers to comply with corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards, though these victories fail to transform the broader capital–labor relationship. However, while contingent coupling acknowledges deviations from the loose–tight binary, it appears to be a transient phenomenon, ultimately leaving the binary framework largely intact. A more comprehensive framework is needed to explain how intraorganizational contention contributes to partial coupling between formal policies and practices and to examine its broader implications for the institutionalization of legal norms.

Contentious coupling

To explain the persistent liminality between loose and tight coupling, this article introduces the concept of contentious coupling, which has two defining elements. First, it describes a pattern of substantive yet constrained alignment between organizational practices and formal commitments. Second, this alignment emerges through the paradoxical effects of contention among organizational members: while contention partially aligns practices with commitments, it simultaneously generates resistance or counterincentives that would not have otherwise occurred, obstructing full alignment.Footnote 2

The first element, substantive yet constrained alignment between practices and commitments, sets contentious coupling apart from both loose and tight coupling. What constitutes “substantive” and “constrained” is inherently relative and best assessed in comparison to alternative measures previously adopted by the organization or implemented within the broader organizational field. If the practices in question go beyond mere symbolic responses but still fall short of plausible ideals, they may be considered substantive yet constrained. For instance, if most states disregard international standards on solitary confinement despite having ratified treaties protecting prisoners’ rights, a state’s legislative adoption of select standards with enforcement mechanisms can be considered substantive, even if it does not achieve full compliance. In such cases, institutionalized norms produce tangible effects, though they may remain inadequate in the eyes of norm proponents.

The second element highlights that this substantive yet constrained alignment arises from intraorganizational contention with paradoxical effects. Social scientists have identified various mechanisms through which contentious efforts to achieve policy goals generate inherent limitations.Footnote 3 This article focuses on one such mechanism: alienation, in which hierarchical domination imposed by some organizational members during contention is perceived by others subjected to it as an affront to personal dignity, fostering apathy, estrangement, and passive resistance. While rooted in Marx’s analysis of economic exploitation, alienation has also been used by sociologists to explain how bureaucratic authority distances individuals from recognizing both the value of their tasks within organizations and their moral worth as human beings (Adler Reference Adler2012; Adler and Borys Reference Adler and Borys1996; Dobbin et al. Reference Dobbin, Schrage and Kalev2015; Hodson Reference Hodson1991, Reference Hodson2001). Unable to openly resist, alienated individuals may engage in passive resistance techniques, such as withdrawal, foot-dragging, and sabotage, as a means of reclaiming personal dignity (Scott Reference Scott1990, Ch.5). While such resistance does not dismantle domination, it can undermine the legitimacy of authority and compromise policy implementation.

The paradoxical effects of intraorganizational contention distinguish contentious coupling from other forms of partial implementation of institutionalized norms. First, contentious coupling is not simply a transitional phase between loose and tight coupling that continuously moves in one direction. While such phases may occur when organizational members push to either tighten or loosen coupling, contentious coupling emerges only when contention itself generates resistance or counterincentives that would not otherwise arise, creating built-in limitations. As a result, contentious coupling tends to be stable and persistent, requiring alternative logics or strategies of contention to resolve. Second, contentious coupling differs from substantive but constrained coupling that occurs when an organization uniformly complies with institutionalized norms while attempting to curb their influence (Bromley and Powell Reference Patricia and Powell2012). A company may choose to partially comply with court orders, just as a state may selectively adopt resolutions from international organizations, both without significant internal dispute. In these cases, barriers to tighter coupling stem from the organization’s collective resistance to external enforcement rather than from internal contention. As I will illustrate below, this distinction matters because each scenario calls for different strategies to achieve tight coupling.

Contentious coupling may not only be widespread but also essential for understanding how institutionalized norms persist within organizational fields. Traditional neoinstitutionalism attributes the reproduction of norms primarily to diffusion through loose coupling. However, in a rationalized world with increasing oversight and professional commitments, purely symbolic policies, structures, and even practices become more difficult to sustain. As Stinchcombe (Reference Stinchcombe1997, 17–18) forcefully argues, there is always “somebody somewhere [who] really cares to hold an organization to the [institutionalized] standards and is often paid to do that.” For institutionalized norms to endure, they must yield at least some substantive effects (see also Bromley and Powell Reference Patricia and Powell2012; Gray and Silbey Reference Gray and Silbey2014; Hallett Reference Hallett2010). By showing how intraorganizational contention drives substantive yet constrained effects of institutionalized norms, contentious coupling explains why these norms retain legitimacy despite their limitations: because they generate tangible outcomes, organizational members persist in advocating for them and addressing their shortcomings, thereby reproducing them – whether intentionally or inadvertently (see Simon Reference Simon2025; Tsutsui Reference Tsutsui2018). Recognizing the internal contention that shapes these limitations thus provides insight into strategies for strengthening and expanding the influence of institutionalized norms.

Human rights law and prisoners’ rights in Taiwan

Taiwan’s transition from thirty-eight years of martial law to a relatively young democracy offers a valuable opportunity to examine the contention among state actors over human rights. On one hand, Taiwanese policymakers have actively engaged with the international human rights regime, primarily to enhance Taiwan’s global standing and differentiate it from authoritarian Mainland China (Y.-J.Chen Reference Chen, Cohen, Alford and Lo2019; deLisle Reference deLisle, Cohen, Alford and Lo2019). Since the 1990s, under pressure from a small but vocal group of human rights advocates, the Taiwanese government attempted – although ultimately failed – to deposit instruments of ratification for major human rights treaties with the United Nations Secretariat (Y.-J. Chen Reference Chen, Cohen, Alford and Lo2019; Huang and Huang Reference Huang, Huang, Cohen, Alford and Lo2019; Chang Reference Chang2009). As an alternative, Congress (the “Legislative Yuan”) has since 2009 enacted a series of “implementation acts” granting these treaties domestic legal force. As of September 2024, Taiwan has adopted implementation acts for five international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which underpins prisoners’ rights against prolonged solitary confinement.Footnote 4

On the other hand, despite Taiwan’s proactive endorsement of human rights, implementation has been hindered by party politics, ideological divides, and administrative resistance. Although the lifting of martial law in 1987 led to a peaceful democratization, culminating in Taiwan’s first presidential election in 1996, many authoritarian-era laws and bureaucratic practices remained intact (Chen and Yeh Reference Chen, Yeh, Cohen, Alford and Lo2019). Even after the enactment of implementation acts, many government officials remained skeptical of the legal significance of human rights treaties (T.C. Chen Reference Chen2019; Kuan Reference Kuan, Huang and Weng2022; Kuo Reference Kuo2013). As I will illustrate, such skepticism persists within key institutions responsible for enforcement, including the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), which oversees compliance among government agencies, and the Agency of Corrections (AoC), which administers prisons and other correctional facilities.Footnote 5 Meanwhile, although Taiwanese courts have the authority to interpret human rights treaties, they have been cautious in their rulings (Chang Reference Chang2012, Reference Chang, Cohen, Alford and Lo2019; Hsu Reference Hsu2014, Reference Hsu2017; Kuo Reference Kuo2015). While recognition of these treaties has improved over time, particularly during President Tsai Ing-Wen’s administration (2016–2024), progress has been slow and uneven across policy areas (T.C. Chen Reference Chen2019; Huang and Weng Reference Huang and Weng2022).

These inconsistent responses to international human rights set the stage for the introduction of prisoners’ rights regarding solitary confinement. Depriving prisoners of social contact causes severe suffering and can lead to lasting mental and physical harm (Haney Reference Haney, Lobel and Smith2018; Reference Haney, Lobel and Smith2020; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Reiter, Gonzalez, Tublitz, Augustine, Barragan, Chesnut, Dashtgard, Pifer and Blair2020; Wildeman and Andersen Reference Christopher and Andersen2020). As a result, the international human rights regime has identified solitary confinement as a potential form of torture, prohibited under core treaties such as the ICCPR and the UN Convention against Torture (CAT). The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the “Mandela Rules,” adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015, provide authoritative guidance on solitary confinement. The Mandela Rules define it as “the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact” (UN General Assembly 2015), which can be used “only in exceptional cases as a last resort,” should not exceed fifteen consecutive days, and should not be applied to children, women, or individuals with mental or physical disabilities. Although these regulations constitute non-binding “soft law” with only a recommendatory status (Cerone Reference Cerone, Lagoutte, Gammeltoft-Hansen and Cerone2016, 16–17), they have gained significant global traction and have influenced other human rights standards (e.g., CPT 2011). The following sections examine how these soft law standards were hardened into domestic law in Taiwan through a contentious process, as rights advocates and policymakers pushed for their adoption while facing resistance from frontline correctional bureaucrats

Data and methods

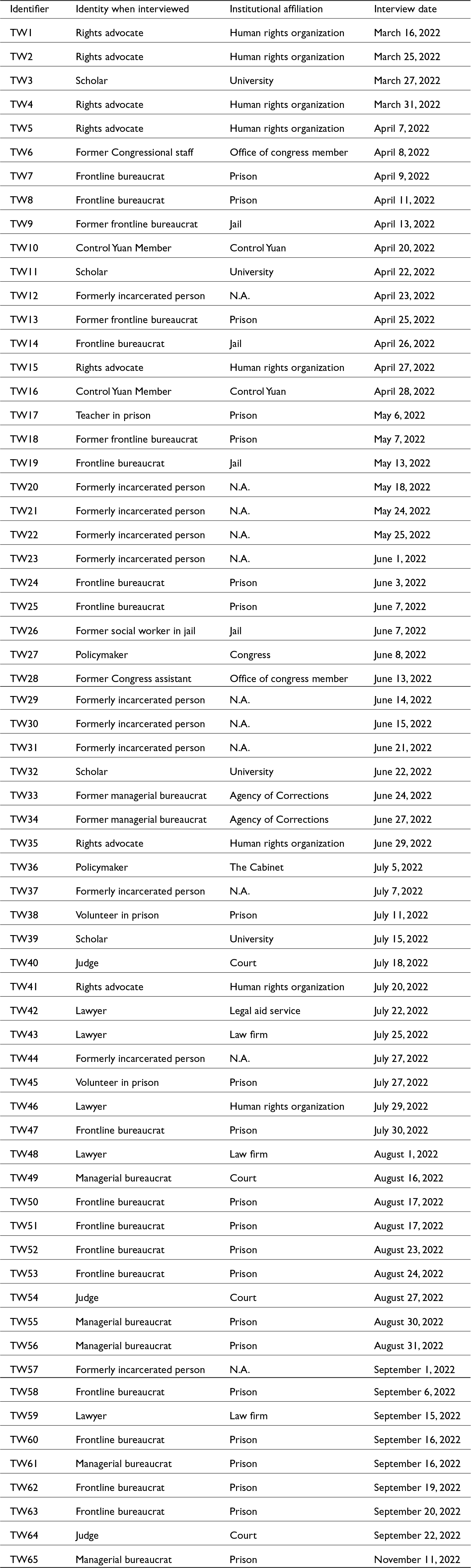

This article draws on in-depth interviews, document analysis, and participant observation to reconstruct the reform process of solitary confinement in Taiwan. I recruited interviewees through two purposive sampling strategies. First, I began by interviewing advocates I knew personally from my experience working in a human rights organization from 2016 to 2018, focusing on those involved in solitary confinement reforms. I then used snowball sampling to expand the pool to other advocates, policymakers, and correctional bureaucrats engaged in the reform process. This approach allowed me to interview nearly all rights advocates and several key policymakers and correctional bureaucrats who participated in the reforms. Second, to mitigate the potential bias of snowball sampling and access perspectives from correctional bureaucrats outside the reform network, I submitted a formal research application to the AoC. Upon approval, I sent interview requests to nineteen of Taiwan’s fifty-one correctional facilities, selecting various types of facilities, particularly those not previously reached through snowball sampling. In total, I conducted 65 semi-structured interviews between March and November 2022 (see Appendix for a list of interviewees). Of these, 53 interviewees were recruited through personal contacts or snowball sampling, while 12 participated via formal research applications. Interviews were conducted in Mandarin, lasted between 40 and 160 minutes, and all but one were audio-recorded. I used an interview protocol that began with participants’ experiences related to the reform, later delving into their perspectives on human rights and the impact of the changes. The protocol was adjusted throughout the fieldwork based on emerging findings and the interviewee’s specific expertise.

To examine the interaction between correctional bureaucrats and rights advocates, I also conducted participant observation in fourteen three-hour meetings convened by the MoJ between April and December 2022, attending remotely after October. With the support of a human rights organization that recruited me as an intern, I was able to observe these meetings and take detailed notes on how rights advocates invoked human rights law and how government officials responded, particularly regarding solitary confinement. These observations were significant because many of the participants had also been involved in the 2018–2019 amendment of the Prison Act, which I had not attended. Observing these later discussions allowed me to compare participants’ accounts of past debates with their current interactions and assess the evolving dynamics of the reform process.

Additionally, I collected and analyzed documents from multiple sources. First, I used the NEAR (Navigating Electronic Agencies’ Records) system (NEAR, n.d.), a public research database containing digitized official documents from all Taiwanese government agencies, to search for materials related to the reforms. I conducted keyword searches for “solitary confinement” and requested access to relevant records, though most were not directly applicable to this analysis except for a few documenting the review process of the Prison Act within the Cabinet (the “Executive Yuan”).Footnote 6 Second, I retrieved legislative records of the Prison Act from the publicly accessible database of Congress (Legislative Yuan, n.d.). Third, I collected court rulings and investigatory reports from the Control Yuan – Taiwan’s ombudsman-like institution – regarding solitary confinement, all of which are available online. Fourth, I obtained minutes from public hearings and government meetings on solitary confinement reform from interviewees. These documents provided robust evidence of the reform process and occasionally offered perspectives from specific agencies or individuals, helping to verify and complement interview data. Finally, I analyzed Facebook posts from the widely known but unofficial Facebook group “Prison Hate” (靠北監所), where correctional officers anonymously submit complaints. While not representative of all correctional officers, the group is widely regarded by both bureaucrats and advocates as a rough gauge of frontline officers’ sentiments (TW10; TW14; TW18; TW50; TW51; TW53; TW56).Footnote 7 I conducted a keyword search for “human rights” within the group and analyzed 81 posts published between its establishment in 2015 and August 4, 2023.

I imported all data into ATLAS.ti for analysis. As part of a broader project comparing the influence of human rights law across jurisdictions, I employed the “flexible coding” method, which follows an abductive epistemology to process large volumes of data while allowing coding and theory-building to co-develop (Deterding and Waters Reference Deterding and Waters2021; see also Tavory and Timmermans Reference Tavory and Timmermans2014). I began with broad, generic index codes, such as “background of reform,” “formal institutional impact,” “relational institutional impact,” and “human rights perception,” which were applied across different jurisdictions. I then focused on Taiwan, systematically examining and verifying the formal and relational impact of human rights, the differences between them, and their relationship to perceptions of human rights. It quickly became evident that while the formal impact of human rights – statutory change and implementation – was considerable, the relational impact and staff perceptions were far more ambivalent. Analyzing this disjuncture led me to identify a paradox between the substantiveness of change and its limitations, shaped by contention among organizational members, which ultimately formed the basis for theorizing contentious coupling. The following sections present the findings, accompanied by illustrative quotes that reflect the perspectives of key stakeholders. While disagreements exist, they do not undermine the validity of the arguments presented.

From loose coupling to apparent tight coupling: the amendment of the Prison Act

This section traces the emergence of concerns over solitary confinement in Taiwan and their evolution into the adoption of the 2020 Prison Act, which explicitly incorporates the Mandela Rules and prohibits prolonged solitary confinement. Because the Act subjects human rights violations to judicial review and codifies substantial reforms implemented since the 2000s, one might be tempted to conclude that the state’s commitment to human rights is now tightly coupled with practice (see T.-Y. Chang et al. Reference Chang, Peng and Lai2021; M.H. Lin Reference Lin2023). Indeed, as a comprehensive overhaul of a statute that had seen only minor revisions since 1954, the new Prison Act marks a significant shift in Taiwan’s penal history, driven largely by persistent human rights advocacy and the unexpected backing of key policymakers.Footnote 8 However, as the following section will demonstrate, characterizing the new status quo as tight coupling is misleading. Passive resistance among correctional bureaucrats persists, revealing the limitations of reform implementation.

Loose coupling between commitments and practices regarding solitary confinement, 2008–2018

Organized advocacy for prisoners’ rights gained momentum through two institutional breakthroughs in the late 2000s (Yang Reference Yang2013; M.H. Lin Reference Lin2023). First, in 2008, the Council of Grand Justices,Footnote 9 Taiwan’s highest court, issued Interpretation No. 653, a landmark ruling that declared restrictions on pretrial detainees’ access to legal remedies unconstitutional and ordered the MoJ and the AoC to review the Prison Act, which had governed prison management since 1946.Footnote 10 Second, in 2009, the Taiwanese government enacted the implementation act for the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), granting these treaties domestic legal force. The act also established a quadrennial review mechanism (hereafter “Periodic Review”), through which international human rights experts assess Taiwan’s compliance with these covenants (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Alford and Lo2019; Huang and Weng Reference Huang and Weng2022).

Leveraging these institutional changes, civil society organizations mobilized under the campaign “Taiwan Action for Prison Reform” (TAPR) to push for prison reform. Activists used human rights law to highlight issues such as overcrowding, inadequate medical care, lack of educational and vocational programs, and physical abuses within prisons, raising these concerns during the Periodic Reviews in 2013 and 2017 (Liao Reference Liao2012; Ministry of Justice 2013, 2017). The Control Yuan validated many of these criticisms through its investigatory powers, repeatedly admonishing the government to comply with its human rights commitments (see, e.g., Control Yuan 2009, 2012, 2013). By the late 2000s, human rights abuses in prisons had become an issue that authorities could no longer ignore.

However, solitary confinement did not emerge as a focal point of advocacy until 2015, when Lin Wen-wei, a correctional officer, publicly exposed its extended use in a Facebook post. Prior to Lin’s whistleblowing, solitary confinement remained a largely obscure issue due to its lack of clear definition and its infrequent use in overcrowded prisons (TW1; TW4; TW15; TW28; TW31; TW32).Footnote 11 Lin’s post described how a young, mentally ill prisoner had been held in solitary confinement for over a year, sparking widespread public concern and drawing attention from legislators and Control Yuan members. In 2016, Yu Mei-nu, a liberal congresswoman, obtained statistics from the AoC revealing that 287 prisoners – out of a total prison population of approximately 63,000 – had been subjected to solitary confinement, in some cases for as long as 153 months.Footnote 12 Citing ICCPR Article 7 and General Comment No. 20, Yu and two other legislators urged the AoC to review and reform solitary confinement practices to align with international human rights standards (Legislative Yuan 2016a, 72-73; 2016b, 469). The issue gained further prominence in 2017, when the National Conference on Judicial Reform (hereafter “National Conference”), a high-profile forum convened by President Tsai Ing-wen, called for explicit regulations on solitary confinement, including clear guidelines on its use, duration limits, and safeguards to ensure basic living conditions (Office of the President 2017, 73).

Facing growing criticism, the MoJ and AoC attempted to demonstrate their commitment to human rights by initiating reforms. However, these early efforts were largely symbolic. Two examples illustrate this pattern. First, the MoJ and AoC began issuing circulars on the use of solitary confinement, but these directives were vague, temporary, and lacked mechanisms for enforcement.Footnote 13 Second, and more tellingly, solitary confinement and broader human rights concerns were largely sidelined during the drafting process for the new Prison Act, which had begun in 2012 in response to Interpretation No. 653. A review of 64 meeting minutes from the drafting process reveals that the term “covenant,” commonly used in Taiwan to refer to human rights treaties, appeared only six times, and concerns about human rights violations under solitary confinement were raised just once.Footnote 14 Interviewees who worked in the AoC at the time noted that the amendment primarily aimed to codify existing practices rather than overhaul the prison system in response to human rights advocacy (TW8; TW33; TW34).

Led by MoJ and AoC bureaucrats, the initial legislative response to external criticism reflected a loose coupling between human rights commitments and actual practices. The Mandela Rules were viewed as too radical for adoption, and solitary confinement was seen as too marginal to merit explicit regulation. As a result, the MoJ’s final draft of the Prison Act simply prohibited the use of isolation as a form of punishment but failed to introduce substantive procedural safeguards to prevent its misuse.

Apparent tight coupling: successful alliance between policymakers and rights advocates, 2018–2020

Beginning in 2018, initial bureaucratic resistance to human rights reforms faced renewed pressure from policymakers committed to substantive compliance with human rights law. Leveraging their political influence, these policymakers pushed for an overhaul of the Prison Act, strengthening the alignment between human rights commitments and correctional practices. A central figure in this effort was Minister without Portfolio Lawrence Su,Footnote 15 a senior official appointed by the president to oversee judicial affairs and policymaking within the Cabinet. Before his ministerial role, Su was a criminal defense lawyer with strong ties to human rights organizations. Upon assuming office, he oversaw the Cabinet’s review of the Prison Act draft submitted by the MoJ, a process typically treated as a formality lasting only a few weeks. However, Su quickly recognized that the draft failed to address criticisms raised during the Periodic Reviews and the National Conference. By neglecting key concerns about human rights violations, he deemed the draft as having fallen short of the “minimum requirements” mandated by international human rights treaties ratified by Taiwan (TW4; TW15; TW36).

Seizing the opportunity presented by the Cabinet review, Su initiated a comprehensive, substantive reassessment of the draft, an unprecedented move that took both correctional officers and human rights activists by surprise (TW1; TW4; TW15; TW34; TW35; Executive Yuan 2018; Ministry of Justice 2018b, 2018c). The review process included government officials and prisoners’ rights advocates from organizations such as the Judicial Reform Foundation (JRF), Covenants Watch, and the Taiwan Association for Human Rights. Over the course of 25 formal meetings and numerous informal negotiations, rights advocates engaged in direct discussions with MoJ and AoC officials about the feasibility of incorporating the Mandela Rules into the Prison Act. With Su’s backing, MoJ and AoC officials found it increasingly difficult to offer only symbolic gestures toward human rights concerns or to downplay the issue of solitary confinement (TW34, TW36; Ministry of Justice 2018a). As one rights advocate noted, “The Mandela Rules are written right there. It’s hard to explain why you would want an alternative of 30 days [for the cap on solitary confinement] or refuse to follow them” (TW15; also TW4; TW41). While officials managed to push back on some proposals from rights advocates, they were ultimately compelled to concede on provisions explicitly supported by the Mandela Rules (TW4).

Su’s effort to revamp the Prison Act also garnered support from other policymakers, though not necessarily due to a shared commitment to human rights. A particularly unexpected ally was Deputy Minister of Justice Josh Tang, who had previously overseen the MoJ’s drafting of the new Prison Act from 2012 to 2018 – a process that, as noted earlier, largely ignored solitary confinement as a human rights concern. However, following Su’s explicit directive, Tang shifted course, likely due to his well-known political pragmatism (TW4, TW8, TW11, TW35). Su also secured backing from members of Congress. While the ruling Democratic Progressive Party’s legislative majority worked in his favor, the bill ultimately gained bipartisan support (Legislative Yuan 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Congress approved the Prison Act within eight months of review, with only minor revisions, marking the most extensive amendments to the law since its enactment in 1946. The new Prison Act, which was promogulated on January 15, 2020, imposed an outright ban on solitary confinement exceeding fifteen consecutive days.

Through collaboration with persistent rights advocates, Su’s intervention significantly tightened the coupling between human rights commitments and correctional practices. Beyond the enactment of the new Prison Act, compliance also appears robust. Since no statistical records were maintained before the amendment, direct comparisons are unavailable. However, watchdog organizations report that prolonged solitary confinement has become nearly obsolete (TW10, TW11, TW38, TW39, TW45). Courts and the Control Yuan have been proactive in monitoring compliance, with only a few documented violations (see Control Yuan 2022). Additionally, some correctional officers noted that their institutions now avoid using isolation even when legally justified, fearing potential controversy (TW8, TW50).

Contentious coupling: the sources and consequences of “human rights upsurge”

While the new Prison Act represents a significant step in implementing human rights law, its impact is constrained in multiple ways. This section examines how these limitations reveal contentious coupling as a more precise characterization of how state practices align with formal commitments. Despite rigorous enforcement of and compliance with the new Prison Act, many correctional officers express serious doubts about human rights and associated reforms. Some of these doubts stem from the inevitable gaps between penal practices and human rights demands. However, a substantial part arises from the enforcement process itself, which is embedded in the rigid hierarchy of the corrections profession. Experiencing relative deprivation and perceiving hypocrisy in this process, even officers who support human rights reforms may develop ambivalence toward them. These perceptions contribute to two forms of passive resistance – formalistic care and resistance spillover – that undermine the authority of human rights and their further institutionalization.

The rights paradox: “human rights upsurge” and its relational roots

Frontline officers’ skepticism toward human rights is encapsulated in their frequent use of the term “human rights upsurge” (人權高漲). One correctional officer explained that the phrase is commonly used among colleagues to describe any perceived improvement in prisoners’ conditions: “Basically, whenever anything’s off or different from before, they go all ‘human rights upsurge’” (TW 8). Practically all interviewees working in prisons recognized the term. For many, it conveys the idea that prisoners now enjoy an excess of rights they do not deserve (TW32, TW33, TW34, TW38, TW55). An analysis of posts from the Facebook group “Prison Hate” confirms this perception. Among the 81 posts containing the keyword “human rights,” only two (2.4%) expressed concern over the inadequate protection of prisoners’ rights, while 51 (62.9%) argued that prisoners enjoy excessive rights, and 36 (44.4%) claimed that correctional officers’ rights are insufficiently protected.

It is unsurprising that human rights reforms provoke complaints within the corrections profession, as they challenge the status quo. The challenge is both practical and ideological. Practically, restrictions on solitary confinement remove a disciplinary tool that many correctional officers have relied upon (TW38, TW58, TW60). Officers who joined the profession before the gradual recognition of prisoners’ rights in the 2000s are particularly affected (see Chang et al. Reference Chang, Peng and Lai2021; Jen Reference Jen2018). While research suggests that solitary confinement is often counterproductive and has effective substitutes (Cloud et al. Reference Cloud, Augustine, Ahalt, Haney, Peterson, Braun and Williams2021; Damsa Reference Damsa2021; Haney Reference Haney, Lobel and Smith2018), its strict regulation has led to frustration among officers. A senior officer acknowledged that restrictions help prevent abuses but argued that the cap on solitary confinement duration is too rigid, eliminating its deterrent function (TW58; also TW38, TW50, TW60, TW62). Another officer with over twenty years of experience remarked:

We’re kinda left with almost no tools [for discipline] these days. It’s like the higher-ups in the AoC want us to keep the prisoners in line and submissive, but they don’t give us many tools. It is a tough job… if things go down, you gotta handle it yourself. Your superintendent won’t watch your back because doing so would only mess up their career. (TW47)

With their custodial duties unchanged, officers reported that maintaining order now depends more on personal skills (TW47, TW50, TW60). Many believe that their superiors blindly adhere to human rights standards without considering frontline challenges.

Ideologically, several officers expressed concern that by elevating prisoners’ rights, the penal system is losing its retributive and corrective functions. Some believe that incarceration should entail a degree of suffering beyond mere deprivation of liberty, a principle they see as increasingly undermined by expanding prisoners’ rights. A senior officer remarked, “[t]he punitive aspect is built into the law. If you take away all these punitive elements, you’re basically. just keeping these folks locked up” (TW60). Another officer argued that prisoners’ rights are being prioritized at the expense of victims’ rights:

There should be some limitations on [prisoners’] dignity here...You’ve made some families unable to support themselves, but here, apart from not being able to walk out the gate, is there anything you can’t get? Basically, nothing. You’ve only lost your freedom. So, I think there can be more restrictions… I don’t think it’s necessary to regulate the length [of solitary confinement]. (TW50; also TW10, TW26, TW55)

These perspectives suggest that while many officers may not reject human rights outright, they believe the extent of reforms has compromised fairness and justice in the penal system.

However, beyond these perhaps unavoidable conflicts, I highlight a more relational and paradoxical source of grievance against human rights: their hierarchical enforcement within a demanding work environment. This paradox arises because while enforcement – driven by the successful alliance between rights advocates and policymakers – ensures compliance with the Prison Act, it also alienates correctional officers who neither have a vested interest in using solitary confinement nor adhere to a retributive ideology. Many of these officers are relatively new to the penal system and have received substantial training in penology, yet they struggle to resonate with human rights reforms. They perceive these reforms as an abuse of power or as hypocrisy that primarily benefits managers’ personal interests. Consequently, the limitations of human rights are endogenous to the very mechanism responsible for their substantive implementation, a paradox central to contentious coupling.

To understand this paradox, it is necessary to examine the power dynamics between managerial and frontline correctional officers, as well as the working conditions of the latter in Taiwan. The correctional profession, as part of the public service sector, primarily recruits officers through standardized national exams, while its managerial echelon is dominated by graduates of Central Police University, a national police academy known for its rigid training. As a result, the correctional profession has long been characterized by a strict hierarchical structure, where junior officers must navigate extensive surveillance, inconsistent directives, and even workplace bullying (TW7, TW14, TW24, TW25, TW26; Jou et al. Reference Jou, Lee, Lin and Hebenton2011; Lin Reference Lin2015, Reference Lin2016). The intensity of working conditions is exacerbated by high prisoner-to-custodial-officer ratios, which place a heavy burden on frontline officers with demanding workloads and exhausting shifts (Control Yuan 2018, 2; see also 2010).Footnote 16 Although the job offers competitive pay compared to other public sector positions, it remains physically and mentally taxing (TW5, TW17, TW24; Control Yuan 2018).

Frontline officers, compelled to implement a series of reforms without recognition of their own demanding working conditions, often feel that the pursuit of human rights is lopsided. Since the Prison Act primarily focuses on the treatment of incarcerated individuals, it does not address correctional officers’ labor conditions. Instead, it expands their responsibilities to monitor and uphold prisoners’ rights – ranging from protections against solitary confinement to improvements in amenities and effective access to legal remedies – while also heightening their exposure to sanctions. As a result, several officers who explicitly support restrictions on solitary confinement expressed frustration that the MoJ and the AoC prioritize prisoners’ rights at their expense. When asked about recent changes in her work, a frontline officer remarked that superiors had become “more and more human rights-protective,” to the extent that they accommodate virtually any prisoner request while failing to address the facility’s labor shortages (TW14). Another officer joked that her superiors “have poured all their love onto the prisoners, but they seldom think about how tough they can be when it comes to us” (TW25; also TW17, TW65). Yet another officer noted that the heightened discourse on prisoners’ rights had led some superiors to “deeply respect” prisoner demands, even when they amount to preferential treatment and complicate frontline officers’ duties. She lamented how this approach has fueled discontent among her colleagues:

We’re implementing new methods to manage the prisoners, but when our superiors treat frontline officers with these old mindsets, a lot of grievances and indignation build up in our chests. So, when we interact with prisoners, we often feel mistreated—like, okay, it’s a different time, a different world; you get all these perks and become ungrateful, and we end up being the scoundrels, huh? The more senior officers would express things like this, and I can understand their grievances and indignation. (TW24)

Similar sentiments are common in the Prison Hate Facebook group. Its moderators explicitly stated in a pinned post that the group was created, in part, to ensure “the prison community can improve, and prisoners’ human rights won’t overshadow those of the officers” (Prison Hate Reference Prison2016) A post from June 23, 2020, just before the new Prison Act took effect, complained that “[a]fter July, it’s gonna be a whole different scene for the prisoners. The higher-ups will be all about prioritizing their human rights, but at the same time, they’re putting the squeeze on the authority of us law enforcement folks” (Prison Hate Reference Prison2020).

Correctional officers’ sense of relative deprivation is further exacerbated by the perception that their compliance with human rights ultimately serves as a means for managerial career advancement. From this perspective, management hypocritically aligns with policymakers’ endorsement of human rights to secure promotions, while leaving the practical challenges and risks to frontline officers. A veteran frontline officer expressed this perceived hypocrisy bluntly: “If we mess up, we get scrutinized and punished, but when the detainees do something, they must be protected… that’s just how society works. The higher-ups have their own agenda – aiming for promotions and getting rich!” (TW47). Similarly, posts in the “Prison Hate” Facebook group frequently claim that managerial support for prisoners’ rights is driven by career incentives. A sarcastic post from August 25, 2022, illustrates this frustration:

Thanks to the incompetence of the Agency of Corrections, managers swept countless cases of frontline staff getting assaulted under the rug just to make their jobs easier and secure their promotions.

Thanks to the Agency’s incompetence, criminals across Taiwan are now brimming with human rights awareness, and the officers can’t keep them in check anymore. (Prison Hate Reference Prison2022)

This post suggests that human rights protections embolden prisoners to challenge correctional officers, but prison managers and AoC officials ignore these operational challenges to cater to human rights initiatives. As a result, frontline officers’ efforts to comply with the Prison Act become little more than stepping stones for their superiors’ career advancement. While the relationship between these reforms and violence against prison staff remains uncertain – in fact, as later discussions illustrate, some violence may be tacitly tolerated by staff as a form of protest to the reforms – the post reflects how grievances toward human rights are intertwined with a broader perception of managerial exploitation.

In summary, the hierarchical enforcement of human rights by prison management alienates correctional officers from recognizing their legitimacy. As Wahl (Reference Wahl2017, 183) observes in the context of anti-torture policies among law enforcement officers in North India, the enforcement of human rights can constrain behavior while simultaneously provoking resistance to internalization. The coupling between policies and practices is thus substantive but constrained. In the next section, I will outline two manifestations of this limitation: correctional officers’ formalistic care toward prisoners, which ostensibly aims to prevent torture, and the spillover of their resistance to human rights into other areas of penal practices.

Consequences of the rights paradox

Formalistic care

One of the major limitations of contentious coupling is how regulations intended to prevent the adverse effects of isolation become mere formalities followed to avoid legal sanctions. The new Prison Act, aligning with the Mandela Rules, defines solitary confinement as confinement for 22 hours per day without “meaningful human contact.” It is permitted only under exceptional circumstances and for a maximum of fifteen consecutive days. However, what qualifies as “meaningful human contact” remains ambiguous. Two hours of genuine consultation with a professional psychiatrist would have vastly different effects on alleviating mental stress compared to, for instance, verbal hostility from staff (see Penal Reform International 2017, 86–89). Furthermore, isolation just under the 22-hour threshold does not legally constitute solitary confinement, yet it can be equally harsh and torturous, especially when prolonged (see Méndez Reference Méndez2015). To prevent isolation from becoming a form of torture, compliance must go beyond technical definitions and instead account for the inherent risks of any form of isolation, ensuring it does not compromise prisoners’ health when its use is unavoidable.

However, in practice, many correctional officers provide only technical compliance with the law when handling cases of isolation. Nearly any interaction with another human being is deemed to meet the standard for “meaningful human contact.” Under the new Prison Act, the AoC (2020) requires frontline officers to record all daily interactions an isolated person has. Yet, rather than ensuring that these interactions are substantive, officers often register any activity they can, such as greetings from prison staff, the act of handing over food trays, or even arguments with other prisoners. In some cases, they also inflate the duration of these activities to meet the two-hour threshold. As a senior correctional officer remarked:

Honestly, even if we didn’t do it for two hours, we’d still fill out the paperwork to make it look like we did. Sometimes, you just don’t have enough time to talk with the prisoner, and there’s not much to chat about! But on paper, we have to fill in the form and cover the two hours. So, when the bosses, inspectors, or the Control Yuan Members come around, [it would be fine] because they pay attention to this kind of stuff. (TW47; also TW19, TW25, TW63)

Another officer observed that while his facility follows the two-hour requirement, the recorded activities – such as solitary exercise or food handling – offer little to no meaningful human contact (Fieldnote 20240722). As long as documentation appears in order and prisoners do not self-harm to attract external scrutiny, correctional officers remain largely indifferent to whether the intent behind the solitary confinement restrictions is truly fulfilled.

Beyond technical compliance, some facilities exploit a loophole in the solitary confinement restrictions by imposing prolonged isolation that does not legally qualify as solitary confinement. Although prisons generally avoid isolation due to limited cell space and potential censure from the AoC, the loophole allows them to manage difficult individuals without investing in medical treatments or therapeutic programs. One officer reported that after the amendment of the Prison Act, his facility complied primarily by allowing prisoners previously held in long-term solitary confinement to exercise alone for two hours daily (TW8). Another officer stated that in his facility, administrators avoid exceeding the fifteen-day threshold by assigning a cellmate for a few days before returning an individual to isolation. “This way, it doesn’t exceed the threshold and technically doesn’t count as [prolonged] solitary confinement” (TW50). While these strategies ensure compliance with the law, they do not stem from genuine concern for the well-being of isolated individuals and leave them vulnerable to the harmful effects of prolonged isolation.

Ultimately, while the new Prison Act introduces safeguards against prolonged solitary confinement, its effectiveness in preventing torture remains constrained. Burdened by heavy workloads and indifferent to the spirit of human rights, most frontline officers I interviewed were untroubled by the formalistic approach they knowingly engage in. Rather than performing ritualistic compliance to reduce uncertainty (Bromley and Powell Reference Patricia and Powell2012; Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977), they simply act to avoid legal repercussions, paying little attention to the broader regulatory purpose of the law. As a former frontline officer put it, none of his colleagues recognized human rights as necessary for prisoners, even if they acknowledged that human rights matter because “we have no choice but to limit our custodial measures accordingly” (TW9; also TW8, TW17, TW19, TW50). Within this context, human rights law produces more than just symbolic effects, yet these effects are often what most human rights advocates would consider meaningful but incomplete progress.

Resistance spillover

While correctional officers do not openly defy restrictions on solitary confinement, their discontent often spills over into other areas of penal practices where passive resistance is more feasible (Hodson Reference Hodson1991; Scott Reference Scott1990). I refer to this phenomenon as resistance spillover. Although I did not observe instances of direct resistance solely triggered by discontent over solitary confinement, such discontent is undoubtedly part of the broader “human rights upsurge” that underpins the following incidents.

One such incident occurred in a juvenile facility in November 2021, when a minor commotion allegedly broke out due to poor food quality (Lee Reference Lee2021). However, a staff member at the facility suggested that the disturbance was intentionally exacerbated by frontline officers in protest against the lenient policies of a newly appointed custodial chief:

That incident happened because… the newly appointed chief explicitly instructed the staff that they were not allowed to beat the students [the detained juveniles], making it very clear. But then he said something he shouldn’t have. He told the staff that if the students were being noisy, so be it—higher-ups wouldn’t blame them for not keeping things under control just because of the noise. Once he said that, the staff basically stopped bothering. If the students wanted to make a racket, let them. Why bother dealing with it? In their view, if they weren’t allowed to use physical punishment, then there was no way to manage discipline. So, they just let the noise escalate, and that’s why the uproar. (TW14)

Although physical punishment in juvenile facilities has been legally prohibited since the 1960s, enforcement remained lax until the recent “human rights upsurge,” which also restricted other disciplinary techniques such as restraints and solitary confinement (TW38, TW45, TW47, TW60).Footnote 17 In response, some frontline officers engaged in passive resistance through withdrawal and foot-dragging, allowing disorder to escalate rather than enforcing discipline. Many informants reported a similar trend of withdrawal and dereliction in other institutions. A senior officer noted that human rights reforms had “gone a bit too far,” leading officers to adopt a mindset where “people just try to avoid trouble – better to do less than take on more” (TW61). Another officer observed that many of his colleagues had effectively “given up” due to fears of lawsuits from prisoners: “They figure if they don’t do anything at all, then there’s no way they’ll get sued” (TW8; also TW11, TW19, TW45, TW58, TW62, TW63). However, this officer also pointed out that many of his colleagues misunderstood the new Prison Act’s restrictions and exaggerated the likelihood of legal action from prisoners.

Another domain where correctional officers channel their discontent is human rights training and their perception of human rights activists. Since 2009, as part of the implementation of ratified human rights treaties, all government agency employees have been required to undergo regular human rights training (Chen Reference Chen2011; Executive Yuan 2022). These training sessions, typically consisting of lectures given by university professors or human rights professionals, have been met with widespread skepticism and disengagement among correctional officers. At the end of one interview, an officer described the routine indifference towards these sessions:

This week, we have to attend a training on the two Covenants, yeah, we have these sessions pretty often, but for most staff, it’s just something to sit through and forget, yeah… not many people really pay attention in these trainings because, like I said earlier, the way things are makes it hard for staff to buy into prisoner rights. Forcing them to take these courses won’t change that—no one’s really listening. I mean, I doubt anyone besides the warden and the secretary can even recite the full title of the two Covenants. I’ve been sitting through these trainings for years, and I don’t even bother remembering their full titles. To most staff, these Covenants just feel like an obstacle—nothing but a burden on our work, bringing only downsides and no benefits. (TW50; emphasis added)

As this officer indicated, attending these training sessions resembles the formalistic care given to isolated prisoners – performed merely to avoid legal consequences, without engagement with the intended objectives.

Indifference toward human rights trainings is often accompanied by hostility toward human rights advocates, who are perceived as self-interested actors seeking recognition or government positions at the expense of correctional officers. This hostility makes it more difficult for rights advocates to gain insight into prison conditions and collaborate with correctional officers on feasible policy recommendations, including those aimed at improving the labor conditions of frontline officers (TW4, TW41). One officer, while expressing support for restrictions on solitary confinement, cautioned against engaging with rights advocates, arguing that “quite a few opportunists” among them prioritize personal gain over meaningful penal reform (TW65; also TW60). A veteran prison volunteer recounted how correctional officers often react negatively to any association with rights organizations: “If I accidentally let it slip to an officer I’m close with, that I attended a meeting at JRF, they’d be like, ‘JRF? What’s your connection to that!?’ You know, the JRF has a really bad reputation [laughs]” (TW38; also TW26).

While correctional officers’ passive resistance does not amount to an organized backlash to reclaim authority (Mansbridge and Shames Reference Jane and Shames2008), it fosters a “dissident subculture” that treats human rights as a mere public transcript (Scott Reference Scott1990), undermining their legitimacy and complicating future reforms. Given that many systemic issues persist in the penal system – including overcrowding, inadequate medical care, meager rehabilitation programs, and widespread stigmatization of prisoners – this growing disillusionment with human rights can have alarming consequences for both policymakers and rights advocates. Correctional officers may become increasingly resistant to future reforms perceived as benefiting prisoners, and even when such reforms are implemented, authorities and advocates will need to closely monitor their execution. Paradoxically, the very act of strict oversight may further deepen distrust and reinforce resistance, perpetuating a cycle of institutional defiance.

Discussion: identifying and addressing contentious coupling

The changes brought by human rights law on solitary confinement in Taiwan are substantive yet constrained. While hierarchical enforcement ensures strong behavioral compliance, it also alienates officers who might otherwise support human rights norms. Unless these hierarchical tensions within the correctional profession are addressed, tighter coupling remains unlikely. At the same time, frontline officers lack the organized power to challenge human rights laws or the broader legal framework, preventing them from engaging in what Reiter (Reference Reiter and Sarat2012, 107) terms “compliant resistance,” where correctional bureaucrats effectively undermine court regulations. Instead, what these officers can do is withdraw from the proactive protection of prisoners’ rights, rejecting a correctional culture that integrates human rights as part of professional identity.

Contentious coupling has significant practical implications, particularly in a relatively young democracy like Taiwan, where both the push for and hesitations about human rights within the state are real. The limitations of coupling do not stem from ambiguous norms or a lack of external enforcement, but rather from relational tensions within the state as an organization. Consequently, what is needed is not merely additional human rights lessons or stricter enforcement – although both remain necessary – but also reforms addressing relational inequalities between frontline officers and management. Such reforms may include skill training in alternatives to isolation when handling challenging situations (TW47, TW50, TW60; see Cloud et al. Reference Cloud, Augustine, Ahalt, Haney, Peterson, Braun and Williams2021); loosening workplace hierarchies to promote democratization in prison management; and encouraging dialogues between human rights advocates and frontline correctional officers. The goal is to cultivate, rather than discredit, a correctional professional identity that aligns with human rights principles (see Dobbin and Kalev Reference Dobbin, Kalev, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017; Dobbin et al. Reference Dobbin, Schrage and Kalev2015). The support of several human rights organizations for the nascent Union of Correctional Officers, which aims to advance progressive correctional models and improve working conditions, represents a promising first step (Union of Correctional Officers, n.d.).

Contentious coupling is not unique to the implementation of prisoners’ rights against solitary confinement in Taiwan. Its two defining elements – (1) contention among organizational members over norm implementation that (2) substantively aligns organizational commitments and practices while also constraining this alignment – are documented in the literature on how institutionalized norms travel. In addition to Wahl’s (Reference Wahl2017) example, Martin (Reference Martin2014a, Reference Martin2014b, Reference Martin2017) identifies similar dynamics in Uganda regarding the implementation of prisoners’ rights against torture. There, top-down institutional reforms sought to establish a human rights-based correctional system, culminating in a new prison act in 2006. While these reforms achieved notable success, particularly in urban areas, they also generated discontent among prison officers caught between maintaining security and adhering to superiors’ orders. To navigate this tension, officers developed what Martin terms “reasonable caning”: a practice officially condemned yet informally accepted as a means of maintaining discipline within an otherwise human rights-compliant prison. Here, correctional officers’ substantive compliance with reforms coexists with their refusal to fully internalize human rights principles.

The dynamics of contentious coupling are also observed beyond human rights contexts. In explaining the historical shift of penal practices from treatment-centered to punishment-centered in California, Goodman et al. (Reference Goodman, Page and Phelps2015) emphasize that preexisting conflicts between “Treatment” and “Custody” staff from the 1940s through the 1960s played a crucial role. These conflicts prevented the treatment paradigm from becoming fully entrenched, leaving gaps that Custody staff later exploited when broader political and cultural shifts occurred. From a contentious coupling perspective, one could argue that the California penal system’s formal commitment to treatment before the 1970s was not tightly, but contentiously, coupled with practices. The struggle of Treatment staff enabled substantive treatment-oriented practices, but these efforts also provoked countermobilization and backlash. When the balance of power shifted toward Custody staff, the paradigm changed, yet the contention persisted (see also Phelps Reference Phelps2016). In this example, the paradox was not driven by alienation under hierarchical enforcement, but by polarization between similarly powerful adversaries lacking mutual trust and mediatory institutions (Barker Reference Barker2009; Bob Reference Bob2019; Ross Reference Ross2007). Future research should continue examining how contentious coupling is triggered by these and other paradox-generating mechanisms.

However, some organizational responses to institutionalized norms may resemble contentious coupling but should be analytically distinguished. These cases typically exhibit only one of the two defining elements of contentious coupling. First, intraorganizational contention over institutionalized norms does not always result in substantive but constrained coupling. Instead, the outcomes may align more closely with conventional loose coupling, tight coupling, or alternative frameworks (Gouldner Reference Gouldner1954; Hallett Reference Hallett2010; Hallett and Ventresca Reference Tim and Ventresca2006). For example, Lynch (Reference Lynch1998) investigates whether a California parole office adopted the “new penological” paradigm, which emerged in the 1980s and emphasizes actuarial risk management over the diagnostic assessment of individual wrongdoers. While parole agents and their managers disputed this new paradigm, the result was largely loose coupling, with field agents maintaining conventional diagnostic practices while symbolically acquiescing to managerial directives. As Lynch (Reference Lynch1998, 861) explains, “[T]he [new penological] model has not trickled down in a straight and direct path to the front lines… The agents were deeply influenced by the popular discourse on crime in defining their priorities and actively subverted directives from management that sought to reorder those self-defined priorities.” Other studies show that opposition to institutionalized norms can be so strong that, despite behavioral gestures toward compliance, no formal policies materialize, as in loose coupling. Ferguson’s (Reference Ferguson2021) “pocket of world society” framework illustrates this, demonstrating how Senegalese political elites’ support for LGBT rights has not substantively altered the criminalization of homosexuality due to resistance from law enforcement (see also Rubin Reference Rubin2021, Ch.7; Tate Reference Tate2007, Ch.7).

Second, substantive but constrained coupling does not always result from intraorganizational contention. Instead, it may stem from uniform organizational resistance to institutionalized norms. In this scenario, the substantive but constrained coupling is shaped by interactions between the organization and external actors, rather than by relationships within the organization among its members. Much of the legal endogeneity literature (Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Uggen and Erlanger1999) falls into this category when it does not explicitly address how intraorganizational contention shapes coupling outcomes. For example, Calavita and Jenness (Reference Calavita and Jenness2015) find that the constitutional recognition of prisoners’ rights in California led to substantive change within the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), including formal recognition of relevant rights and expanded grievance procedures. However, these procedures provided only limited protection, as few grievances prevailed due to the wide discretion afforded to prison security concerns. In this case, the coupling between CDCR practices and its formal commitment to prisoners’ rights is substantive yet constrained, though not contentious within the CDCR.