In recent months, COVID-19 has upended normal daily life, education, and work across the globe. Decisions about school and workplace closures and reopenings have substantial implications for nearly everyone, often pitting health concerns against consumer preferences and economic considerations. In this article, we explore whether the lack of representation of women among both political and workplace decision makers may cause the COVID-19-related interests of female citizens and female workers to be discounted.

We find that women tend to share distinctive perspectives regarding COVID-19 that emphasize caution far more than is the case for their male counterparts, and we show that the gender difference tracks across political parties. We also demonstrate that both female workers and female workplace leaders have fundamentally different preferences than men concerning COVID-19 in the workplace.

In light of the poor representation of women among decision makers in most U.S. industries and in politics, the results of this analysis suggest that regulations about COVID-19-related issues are likely to be less focused on the protection of individuals from the coronavirus than might otherwise be the case if women were equally represented in leadership roles in the United States. Ultimately, we argue that COVID-19 creates a form of interaction of the political and business realms that may be especially harmful to women. Specifically, we conclude that women face a representational “double whammy” regarding COVID-19: their lack of representation among workplace leaders creates problems that are being compounded—rather than redressed—by unequal political representation. We conclude the article by discussing suggestive signs that women have recently been moving away from President Donald Trump at disproportionately higher rates, potentially because of his positioning on COVID-19.

METHODOLOGY

We examine these issues using large random national samples of Americans collected by Gallup via web surveys. The Gallup Panel is a nationally representative, probability-based survey panel of adults, and the data are weighted according to demographic characteristics to reduce nonresponse bias and improve the representation of the U.S. population.Footnote 1 Studies indicate that probability-based panel polls can provide estimates of public opinion that tend to be at least as accurate as those of traditional telephone polls (MacInnis et al. Reference Macinnis, Krosnick, Ho and Cho2018; Yeager et al. Reference Yeager, Krosnick, Chang, Javitz, Levendusky, Simpser and Wang2011). We use these data for all the analyses that follow, with the analyses of workers and workplace leaders making up a subset of the total sample.

We included data collected from May 18 to June 14, 2020, a time when initial reopening decisions were actively being implemented in many parts of the country. The questions asked in the survey were largely focused on COVID-19 concerns, individual preferences, and workplace structure; there were no questions specifically about COVID-19-related policy on the survey. Especially as an emergent policy area, it seems unlikely that there would be a substantial discrepancy between personal preferences and policy preferences that would further diverge by gender, but this is a potential caveat to note.

COVID-19 VIEWS BY SEX AMONG U.S. ADULTS

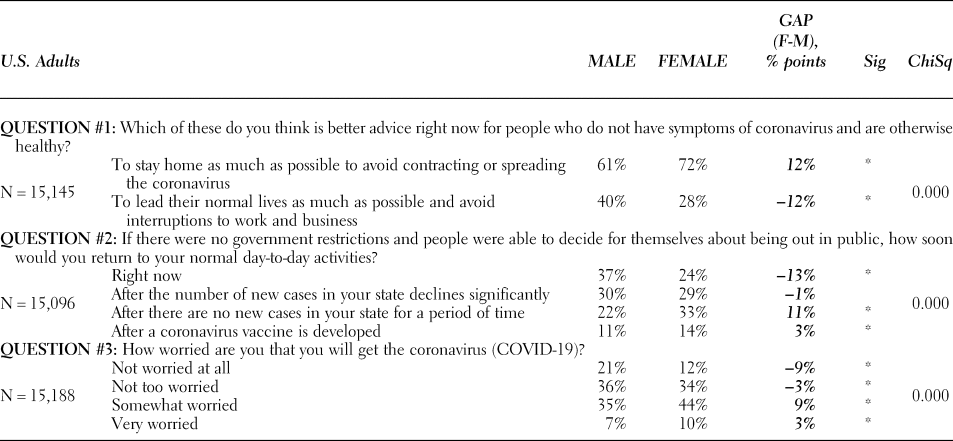

The divergence between women and men across a wide range of questions concerning COVID-19 is striking. Table 1 shows that women express substantially greater levels of concern than men on a wide variety of COVID-19 dimensions.

Table 1. COVID-19 views and sex (U.S. adults)

* indicates differences between women and men that are significant at .05 or better.

These patterns are notable given that women seem to be carrying a disproportionately greater share of the COVID-19-related care-giving load at home, such as child care and remote schooling (see, e.g., Cohen and Hsu Reference Cohen and Hsu2020; Miller Reference Miller2020).

Of course, it is also the case that women tend to be Democrats, and Democrats tend to have more cautious views on COVID-19 relative to Republicans. As such, we examine whether the gender differences shown are a reflection of the partisan gender gap.

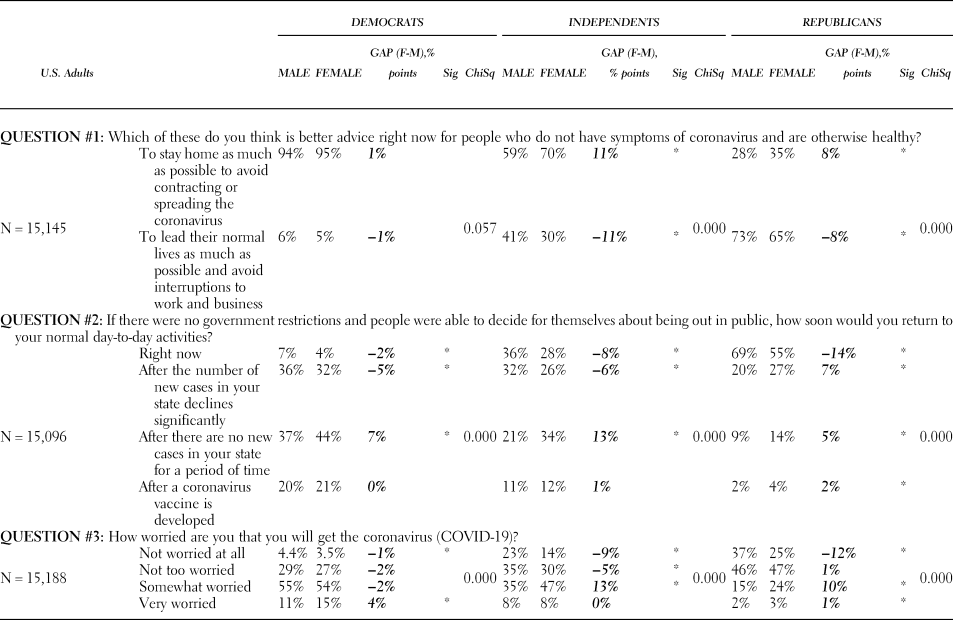

Table 2 shows that is not the case. Across both parties and among political independents men tend to be substantially less concerned and cautious about COVID-19 compared with their female copartisans.

Table 2. COVID-19 views by sex and party identification (U.S. adults)

* indicates differences between women and men that are significant at .05 or bett

Appendix A in the supplementary material online shows a corresponding pattern of results based on multivariate analyses with the inclusion of a series of control variables.

Our results match up with research on previous respiratory diseases across the globe. Specifically, Moran and Del Valle (Reference Moran and Del Valle2016) conducted a meta-analysis of 85 studies of responses to respiratory outbreaks around the world and found that women were approximately 50% more likely to practice nonpharmaceutical preventative behaviors (i.e., using masks, extra handwashing, etc.) during outbreaks than men.

Establishing why sex differences exist in responses to epidemics is beyond the scope of this article, although our findings suggest some possibilities. Studies have found that the views of men and women tend to differ when risk is involved. In particular, scholars have found that women have a greater preference for risk reduction on environmental issues when safety risks are involved (Bord and O'Connor Reference Bord and O'Connor1997; Norrander Reference Norrander and Whitaker2008). Our results seem consistent with a lower perception of risk by men than by women, since we find that women are not just more likely to prefer a cautious approach to COVID-19 but also more concerned than men about catching the coronavirus, even though men are far more likely die from it (Reeves and Ford Reference Reeves and Ford2020).

WORKPLACE DIFFERENCES IN COVID-19 PREFERENCES BETWEEN MEN AND WOMEN

Given the rapid spread of COVID-19, workplace decisions have critical importance for the economic livelihood and safety of employees. As a result, we examine whether there is a gender gap among workers regarding responses to COVID-19 and, in turn, whether differences exist between workplace leaders versus nonleader employees.

Questions regarding COVID-19 in the workplace were asked of a subset of the Gallup panelists represented in the analyses who had been employed over the seven days prior to the day the survey was taken. When asked which option describes their role or job responsibilities at work, 21% of employed male respondents and 13% of employed female respondents selected “I am a leader who manages others” (coded as “leaders”), while the balance selected nonleadership descriptions of their role at work (coded as “workers”).Footnote 2

The “Workers” column of Table 3 shows a persistent gender gap. Female workers are significantly more concerned about the safety of returning to work, are more likely to prefer to continue working at home because of COVID-19-related concerns, and anticipate a longer duration of continued disruption.

Table 3. COVID-19 views by sex for workers versus workplace leaders (employed U.S. adults)

* indicates gender differences that are significant at .05 or better.

A related question is whether the preferences of female workers would be better represented by female workplace leaders as decision makers, which requires first identifying whether a similar gender gap regarding caution toward COVID-19 is also observed among their leaders.

Table 3 confirms that female workplace leaders are also more likely than their male counterparts to take a cautious approach to COVID-19.

The multivariate analyses in Appendix B allow us to confirm that gender is a significant determinant of COVID-19 views in the workplace both with and without interactions between sex and leadership. Controls were included for partisanship (as dummies for “Republican” and “Independent”), low-density population (rural/small town), married, parent, college graduate, race/ethnicity (dummy coded as white, non-Hispanic), age 65 or older, high health risk for COVID-19, high income (household income of $120,000 or more) and low income (household income of $24,000 or less), essential worker,Footnote 3 and week of survey administration.

In short, all of the analyses point in the same direction: male workers are far more bullish about returning to work life as usual than their female colleagues, and similarly gendered patterns exist among workplace leaders.

POTENTIAL WORKPLACE IMPLICATIONS

From the foregoing analyses, we can conclude that female business leaders would be likely to voice different perspectives on COVID-19-related workplace policies than their male colleagues. But how likely are they to have an effective platform for doing so?

Just 30% of the self-described workplace leaders in our sample were female, reflecting a strong male skew in leadership across the majority of U.S. industries and workplaces; moreover, gender imbalances in leadership tend to be even greater at the highest levels of decision-making for the largest employers. For example, just 7.4% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are female (Hinchliffe Reference Hinchlifee2020; see also Yanosek, Ahmad, and Abramson Reference Yanosek, Ahmad and Abramson2019). It is notable as well that even in fields that are mostly composed of female workers, the leadership still skews heavily male: for example, only 3% of health care CEOs and medical division chiefs are female (compared with 80% of health care workers), and only one-quarter of school district superintendents are female, while just over three-quarters of K–12 teachers are women (Rotenstein Reference Rotenstein2018; Superville Reference Superville2016).

Those mostly male workplace leaders are probably unlikely to feel strong pressure to factor in the distinctive COVID-19-related preferences of female workers. Leaders outside of politics do not tend to be democratically elected, generally holding powers more akin to autocrats or even dictators (Wadhwa Reference Wadhwa2016). Ultimately, the exclusion of women from leadership across so many industries strongly suggests that female employees are likely to find themselves pressured or even required to return to workplaces sooner than it feels safe to them, and, by extension, once returning, they may also find fewer safety precautions in place than they prefer.

POTENTIAL POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS

The political realm could potentially serve as a bulwark to prevent female workers from working under conditions they deem unsafe. Unfortunately, women are also descriptively underrepresented across all levels of politics; moreover, the vast majority of female office holders hail from the Democratic Party (for the most recent numbers, see CAWP 2020). There is active debate about the degree to which co-partisanship versus shared gender most effectively promotes the interests of women. But to the extent that descriptive representation does matter, there is reason to think that healthcare might be one of the policy arenas where it might matter a good deal (Swers Reference Swers2016).

Might this pandemic cause women—and perhaps Republican-leaning working women in particular—to become especially concerned about the relative lack of female decision makers both at work and in politics? If Republican leaders continue to minimize the need for safety measures around COVID-19 (Hellmann Reference Hellmann2020; Wildermuth Reference Wildermuth2020), could it lead to a further shift among women in the short term toward a vote for Joe Biden over Trump, or away from the Republican party in the long term?

Partisanship tends to be “sticky,” and candidate preference tends to be closely tied to partisanship (see, e.g., Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). These are not normal times, however, and COVID-19 is not a normal issue. The degree to which this pandemic creates what for many may feel like fundamental concerns about economic and corporeal survival—not just for individuals but for entire households and communities—should not be underestimated. It is thus interesting that some early indications have emerged that Trump has been losing support among women to an even greater extent in recent months. For example, some polls found that the drop in those preferring Trump over Biden was particularly marked between March/April and May/June 2020 (Cohn Reference Cohn2020). With other factors in play during that same time period, a clear causal relationship cannot be isolated; moreover, those results do not isolate female employees specifically. However, results such as those provide some suggestive evidence that the Republican Party may be facing a new cleavage that may further peel away female support for Republican candidates, thereby potentially expanding an already considerable partisan gender gap.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000628