Introduction

Sardinian is a Romance language spoken almost exclusively on the island of Sardinia, an autonomous region of Italy. Sardinian and Italian are not mutually intelligible; there is considerable structural distance between the two linguistic systems, at all linguistic levels (Loporcaro Reference Loporcaro2009: 162–171).

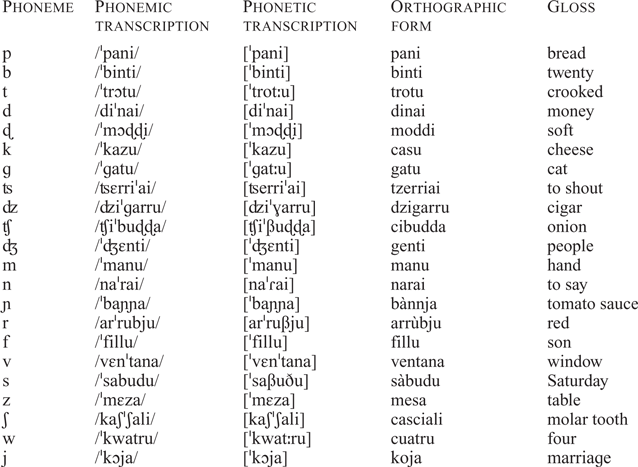

Sardinian can be subdivided into two main dialectal subgroups: Campidanese – spoken in the southern part of the island – and Logudorese-Nuorese – spoken in the central-northern region. In the articulated classification provided by Virdis (Reference Virdis, Holtus, Metzeltin and Schmitt1988) four regional varieties are identified (Figure 1): Campidanese, Logudorese, Nuorese and Arborense – spoken in the west-central region and defined in negative terms (Virdis Reference Virdis, Holtus, Metzeltin and Schmitt1988: 904), since it shows some isoglosses communal to Logudorese and others in common with Campidanese.

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of the varieties in Sardinia (Virdis Reference Virdis, Holtus, Metzeltin and Schmitt1988: 905).

Two other language varieties closely related to the Italian linguistic domain are spoken on the island: Gallurese, spoken in the north-east, which is considered here a variety of Corsican, and Sassarese, an autonomous Italian dialect spoken in the north-west of the island (specifically in the towns of Sassari, Stintino, Porto Torres and Sorso) (Virdis Reference Virdis, Holtus, Metzeltin and Schmitt1988, Putzu Reference Putzu and Stroh2012, Loporcaro & Putzu Reference Loporcaro, Putzu, Paulis, Pinto and Putzu2013). Two other minority languages are spoken in Sardinia: Algherese, an archaic variety of Catalan, is spoken in the town of Alghero, and Tabarchino, an archaic variety of Genoese, is spoken in two small islands of the south-west, Sant’Antioco (Calasetta) and San Pietro (Carloforte).

There are no reliable data on the number of Sardinian speakers. The only available information concerns the self-evaluation of Sardinian people about local varieties. The survey conducted by Oppo (Reference Oppo2007), administered to 2437 Sardinian people, shows that 68% of the subjects claim to speak one of the local varieties of Sardinia, but this survey does not provide any data on the number of Sardinian speakers (see also Pinto Reference Pinto and Paulis2013).

The distance between Sardinian and Italian is exemplified by the following phonological and phonetic features. Sardinian is characterized by:

a system of five vowels, while Italian shows seven vowel phonemes (see further below)

the maintenance of Lat(in) Ĭ and Ŭ, e.g. NĬVE(M) > Camp(idanese) Sard(inian) nii Footnote 1 [ˈnii] vs. It(alian) neve [ˈneve] ‘snow’, BŬCCA(M) > Camp. Sard. buca [ˈbukːa] vs. It. bocca [ˈbokka] ‘mouth’

the presence of metaphony (see further below)

the lenition of intervocalic plosives, e.g. SABBATU(M) > Camp. Sard. sabudu [ˈsaβuðu] vs. It. sabato [ˈsabato] ‘Saturday’

the retroflex geminate [ɖɖ] from Latin -LL-, which is preserved in Italian [ll] e.g. CEPULLA(M) > Camp. Sard. cibudda [tʃiˈβuɖɖa] vs. It. cipolla [tʃiˈpolla] ‘onion’

At the morpho-syntactic level, Sardinian is characterized by:

-

the morpheme -s as a plural mark, e.g. Camp. Sard. gatu [ˈɡatːu] (sg), gatus [ˈɡatːuzu] (pl) vs. It. gatto [ˈɡatto] (sg), gatti [ˈɡatti] (pl) ‘cat, cats’

the definite article derived not from Latin ILLUM as in Italian, but from Latin IPSUM, e.g. Camp. Sard. su cani [suˈɣani] vs. It. il cane [ilˈkane] ‘the dog’

the progressive form with the verb ‘to be’ (< Lat. ESSE), instead of the verb ‘to stay’ (< Lat. STARE), e.g. Camp. Sard. seu papendi [ˈseuβaˈpːɛndi] vs. It. sto mangiando [sto manˈʤando] ‘I am eating’

periphrastic forms for future and conditional (Virdis Reference Virdis, Holtus, Metzeltin and Schmitt1988, Reference Virdis2003), instead of synthetic forms, as in Italian, e.g. Camp. Sard. apu a papai [ˈapːu aˈβapːai] vs. It. mangerò [manʤeˈɾɔ] ‘I will eat’

The linguistic history of the island mirrors the sequence of the external dominations. Very briefly, after the prehistoric period, the different phases are: the Phoenician period (from the 9th century bc to the of the 6th century bc), the Punic period (from the end of the 6th century bc to 238 bc), the Roman age (238 bc – ad 455), the occupation by the Vandals (ad 455–535), the Byzantine phase (ad 535–10th century), the period of the so-called ‘Giudicati’ (which were autonomous state entities ruled by kings called Giudici ‘Judges’, conventionally concluded in 1409), the Aragonese domination (from 1323), the Spanish period (1479–1713), the Austrian years (1713–1718), the Savoy period (from 1718) and, finally, the Italian period, from 1861 (Blasco Ferrer Reference Blasco Ferrer1984; Putzu Reference Putzu and Stroh2012: 180). It is important to cite these historical periods of outside domination because they have left influences on the Sardinian language. In the Sardinian lexicon in particular it is possible to identify different strata of lexical borrowings resulting from the contact with different languages (Wagner Reference Wagner1951, Putzu Reference Putzu and Stroh2012).

Sardinian does not have a standard variety – in the sense of a codified written variety, used as a model by all Sardinians (see Ammon Reference Ammon, Ammon, Dittmar, Mattheier and Trudgill2004) – although there have been some proposals for its standardization. In Italian legislation it is considered an official minority language. Specifically, there are two laws protecting linguistic and cultural Sardinian specificity: the National Law n. 482 of 15 December 1999, which recognizes Sardinian as a minority language, and the Regional Law n. 26 of 15 October 1997, which promotes Sardinian culture and language. The latter allows the use of Sardinian in public administration. In recent years, the Sardinia Regional Administration presented two proposals for an official standard language variety reserved for documents issued by the regional administration: Limba Sarda Unificada (LSU; Unified Sardinian Language) and Limba Sarda Comuna (LSC; Common Sardinian Language), both developed by a scientific committee. The first model, LSU, published in 2001, was a variety presented as a compromise among all Sardinian varieties, but de facto based on the Logudorese variety (see Calaresu Reference Calaresu2002). In 2006 the Sardinia Regional Administration decided to adopt another official standard, LSC, based mainly on a variety spoken in the island’s central areas (see Calaresu Reference Calaresu2008). In the same year, the Sardinia Regional Administration undertook the translation of of legal-administrative documents into this official variety (see Putzu Reference Putzu and Stroh2012: 177). Furthermore, at the end of 2014 there was a regional law proposal aimed at promoting the teaching of Sardinian at all school levels.

Although Sardinian still lacks a standard variety, scholars identify two main macro-varieties, used almost exclusively in literary contexts: the so-called ‘literary Logudorese’ and ‘general Campidanese’. The first is characterized by the formal register of common Logudorese, based on the varieties of central Logudorese with some influences of north-western Logudorese, while the model of the latter is the formal upper-class variety of the Cagliari dialect (Virdis Reference Virdis, Holtus, Metzeltin and Schmitt1988: 897; Paulis Reference Paulis, Argiolas and Serra2001: 164–165; Dettori Reference Dettori, Cortelazzo, Marcato, De Blasi and Clivio2002: 901–902).

Nowadays, Sardinian is spoken almost exclusively in informal contexts, although in the last few years there have been sporadic attempts by some politicians to speak Sardinian in institutional contexts, for example in regional council meetings.

Cagliari Sardinian

The dialect spoken in the regional capital, Cagliari, belongs to the Campidanese variety. Cagliari Sardinian is an endangered urban variety (Loporcaro & Putzu Reference Loporcaro, Putzu, Paulis, Pinto and Putzu2013: 205): native speakers are very few in number, not only among young people but also among the elderly population. This fact is strongly connected to the situation of language transmission, which seems to be highly compromised, because Cagliari Sardinian speakers have stopped speaking their native language with their children and Italian has become the main spoken language. This is a general tendency characterizing urban contexts in Italy (Dal Negro & Vietti Reference Dal Negro and Vietti2011).

As with the language in general, there are no precise data available on the number of Sardinian speakers in Cagliari. In the survey by Oppo (Reference Oppo2007), 58% of Cagliari interviewees claim to speak Sardinian. However, this number contrasts with the 31% reported by Pinto (Reference Pinto and Paulis2013: 136–137), based on a questionnaire including tests aimed at verifying the knowledge of speakers. In their survey, on a sample of 145 subjects, almost 25% of people claimed to speak Sardinian but demonstrated weak competence or no competence in the language. The sum of these two percentages is very close to the 58% reported by Oppo (Reference Oppo2007). It is thus worth noting that both of these surveys reveal a positive attitude towards Sardinian, in that people claim to know Sardinian even if their competence in it is low (Pinto Reference Pinto and Paulis2013: 137). This positive attitude to regional languages and dialects has been noted across the whole of Italy since the 1990s (Berruto Reference Berruto, Beccaria and Marello2002, Dal Negro & Vietti Reference Dal Negro and Vietti2011).

Studies on Sardinian linguistics have always focused on rural varieties, and have thus paid little attention to the urban Cagliari dialect. The phonetic features of the Cagliari dialect are discussed in Wagner (Reference Wagner1941/1984), Virdis (Reference Virdis1978), Blasco Ferrer (Reference Blasco Ferrer1984), Paulis (Reference Paulis1984), Atzori (Reference Atzori1986), Fontana (Reference Fontana1996), Dettori (Reference Dettori, Cortelazzo, Marcato, De Blasi and Clivio2002), Cossu (Reference Cossu2013), and sociolinguistic data on this variety are included in recent work by Paulis et al. (Reference Paulis, Pinto and Putzu2013) and Rattu (Reference Rattu2017). The current work seeks to provide a general phonetic description of Cagliari Sardinian, although some features are not exclusive to this urban variety.

Speech corpus

In the following sections I outline the consonantal and vowel inventory. I then illustrate in more detail some patterns of segmental variation typical of the dialect. These observations are based on recordings made in 2015–2016. Seventeen interviews were collected by means of semi-structured ethnographic interviews, focused on topics of interest to native-speaker consultants, for example the history of the religious confraternities of the towns, religious rites, changes of the town from past to present, the lack of services in Cagliari, etc. The interviews – individual and group interviews – were recorded at 44,100 Hz and 16-bit depth with a Zoom H5 recorder.

The speaker sample is made up of fifteen men and eight women, all born in Cagliari. The age range is 15–85 years. Given the qualitative nature of this work, I refer to four representative consultants. These consultants live in four neighbourhoods of the town. MM37 is a 37-year-old man from the neighbourhood of Marina, CF73 is a 73-year-old woman from Castello, VM46 is a man aged 46 years from Villanova and IsMM57 is a 57-year-old man from Is Mirrionis. These consultants’ recordings have been selected because of their good acoustic quality and because they include typical phonetic traits of the dialect. Spectrograms used to describe phonetic features under investigation have been obtained by means of the PRAAT software (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2017).

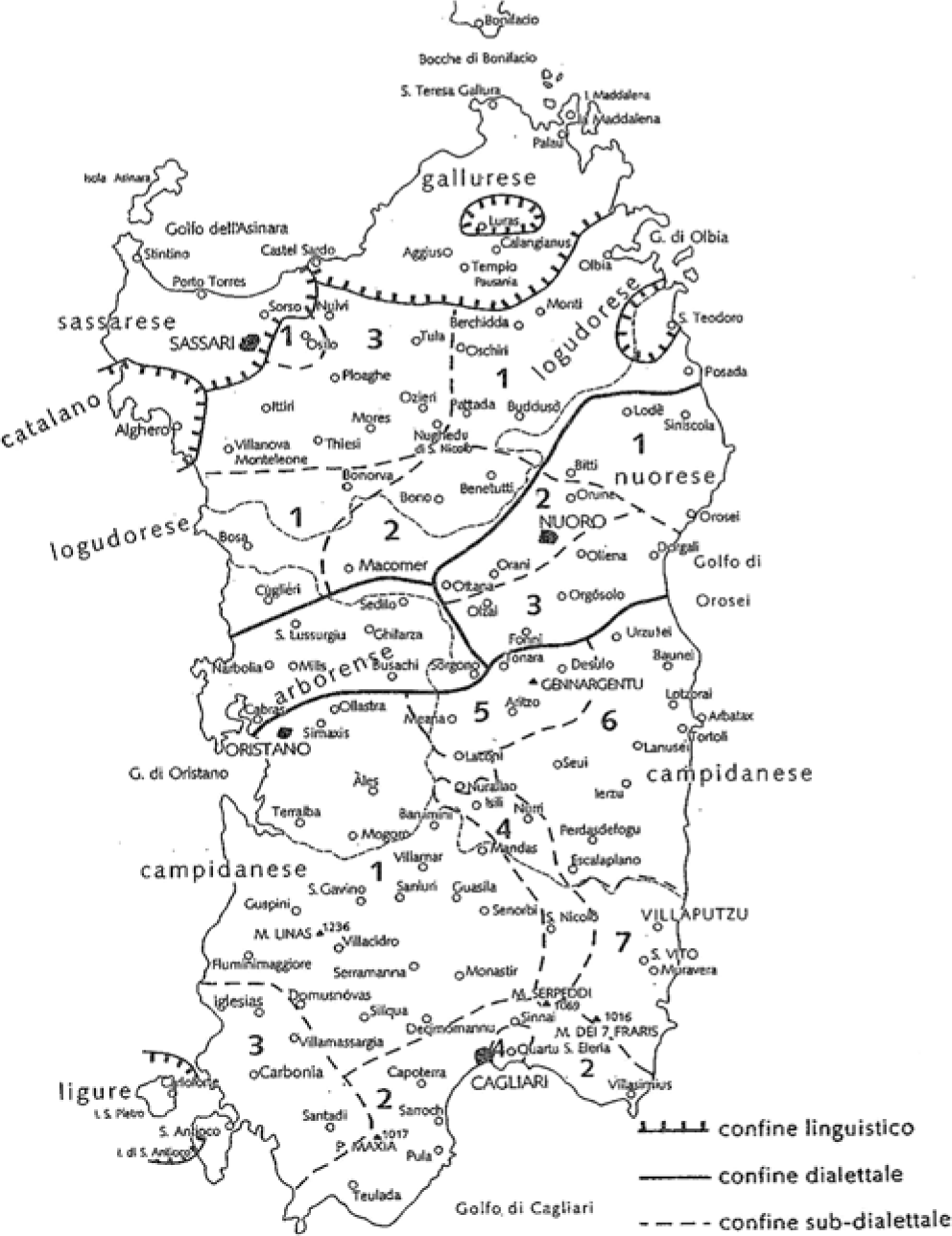

Consonants

The consonantal phonemic system coincides with that of ‘general Campidanese’ (see Virdis Reference Virdis1978) although the Cagliari dialect has some characteristic allophones, described below. In the consonant table below, allophones are set in brackets.

Obstruents

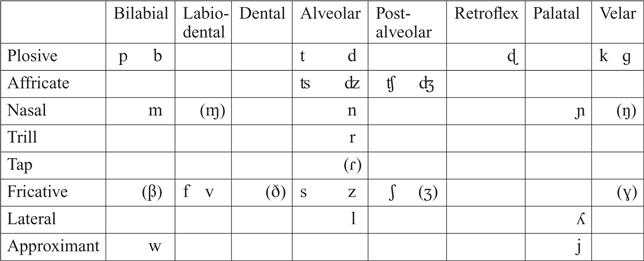

The three voiceless plosives /p t k/ are realized in three distinct ways depending on context: (i) word-initially they are realized as [p t k]; (ii) in intervocalic environments across word boundaries – also when followed by /r/ – they are lenited to voiced fricatives [β ð ɣ], e.g. mancai pentzat [ˈmaŋkai ˈβɛntsaɾa] ‘maybe s/he thinks’, su tempus [su ˈðempuzu], ‘the time’, de conca [de ˈɣɔŋka] ‘of head’ (Figure 2), sa pratza [sa ˈβrattsa] ‘the town square’, su trigu [su ˈðriɣu] ‘the wheat’, sa crai [sa ˈɣrai] ‘the key’; and (iii) in word-medial intervocalic position, lenition is blocked and they are produced with a long duration, which corresponds to the duration of typical geminate stops in Italian (see Ladd & Scobbie Reference Ladd, Scobbie, Local, Ogden and Temple2003; for /t/, see also De Iacovo & Romano Reference De Iacovo and Romano2015), e.g. convocau [koɱvɔˈkːau] ‘called’ (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Spectrogram of item de conca [de ˈɣɔŋka] ‘of head’.

Figure 3: Spectrogram of item convocau [koɱvɔˈkːau] ‘called’.

However, the realizations of long duration produced in word-medial intervocalic position do not contrast with the singleton voiceless plosives because historically the Latin voiceless plosives underwent a lenition process in intervocalic position (e.g. [nɛˈβɔði] < NEPOTE(M) ‘nephew, niece, grandchild’) and synchronically are lenited to [β ð ɣ] in external sandhi, that is, at word boundaries, as already mentioned. Therefore, ‘there is a close link between gemination and intervocalic lenition …such that “geminate” is essentially equivalent to “not lenited”’ (Ladd & Scobbie Reference Ladd, Scobbie, Local, Ogden and Temple2003: 168).

The lenition of the original voiceless plosives is strictly connected with the evolution of the Latin voiced plosives. These sounds, in intervocalic position, generally disappeared (e.g. PEDE(M) > [ˈpɛi] ‘foot’; FABULA(M) > [ˈfaula] ‘lie’), through an intermediate phase of voiced fricatives. Evidence of this phase is seen nowadays in a small set of words in Campidanese Sardinian, where the Latin voiced plosives do not disappear and are realized as their voiced fricative counterparts, e.g. NIDU(M) > [ˈniðu] ‘nest’, NUDU(M) > [ˈnuðu] ‘nude’, FRIGIDU(M) > ‘ [ˈfriðu] cold’ (see Virdis Reference Virdis1978: 50). The process of lenition affecting the Latin voiced plosives might have favoured the sonorization and spirantization of the Latin voiceless plosives (Paulis Reference Paulis1984: XLIII). Given these considerations, it is possible that the Latin voiceless plosives became the Sardinian voiced fricatives through an intermediate phase of voiced plosives and then underwent a process of lenition. These historical processes of lenition involving the Latin plosives determine a difficulty in establishing how to synchronically analyse the Cagliari Sardinian lenited forms from a phonological point of view. For the voiced fricatives [β ð ɣ], Virdis (Reference Virdis1978) identifies phonemic opposition with /b d ɡ/ as exemplified by some minimal pairs, though they include only phrases, e.g. sa bena [sa ˈbːɛna] ‘the blood vessel’ ∼ sa pena [sa ˈβɛna] ‘the pain’; funt duas [ˈfunti ˈdːuaza] ‘they are two’ ∼ funt tuas [ˈfunti ˈðuaza] ‘they are yours’; a gatu [a ˈɡːatːu] ‘to the cat’ ∼ agatu [aˈɣatːu] ‘I find’. However, it is highly debatable to regard [β ð ɣ] as phonemes because their realization is always context-dependent – they occur only in intervocalic environments.

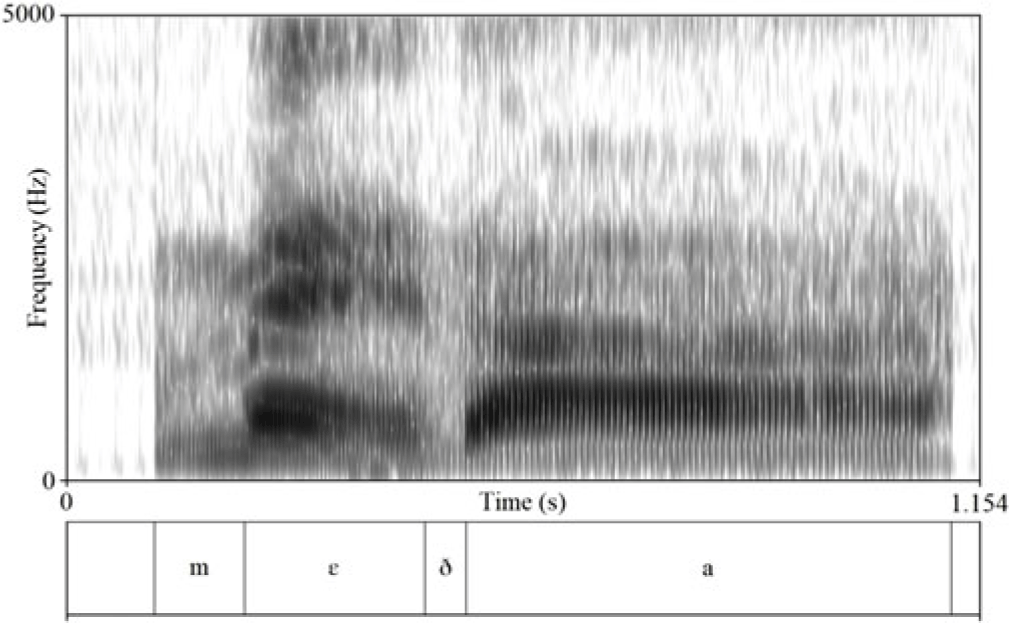

The treatment of the plosives in the loanwords sheds light on the relationship between plosives and voiced fricatives from a phonological point of view. In the loanwords, intervocalic /p t k/ always remain invariant and are produced with a long duration, e.g. Cat(alonian) aturar >[atːuˈɾai] ‘to stay’, It. Scatola > [ˈskatːula] ‘box’, so they never undergo lenition. On the other hand, /b d ɡ/ can remain invariant with a geminate pronunciation, e.g. dd’at acabada [ɖɖ aɾ akːaˈbːaɾa] ‘s/he stopped it’ (acabai < Cat. acabar ‘to stop’) or can undergo a spirantization process, e.g. Sp(anish) acudir > [akːuˈðiɾi] ‘be on time’; Cat. Bossinada > [bussiˈnaða] ‘slap’; Sp. Dudar > [duˈðai] ‘to doubt’; Sp. de badas > [deˈbːaðaza] ‘in vain’, It. Bottega > [buˈtːɛɣa] ‘small shop’ (see Virdis Reference Virdis1978). The treatment of these loanwords leads us to hypothesize that synchronically the underlying phonemes for [β ð ɣ], derived from the Latin intervocalic voiceless plosives, could be /b d ɡ/. However, this issue remains open to further in-depth phonological investigations because it is hard to assign the surface lenited forms to one set of plosives or the other, since even retracing historical processes, they do not lead to a straightforward phonological analysis. Given the above perspective, Cagliari Sardinian voiced plosives /b d ɡ/ could be seen as having the following realizations: (i) word-initially as [b d ɡ]; (ii) in word-medial intervocalic position as [β ð ɣ], e.g. meda [ˈmɛða] ‘much’ (Figure 4) – that is, in the same way as /p t k/ are realized across word-boundaries; and (iii) across word boundaries, lenition is blocked and they are generally produced with a long duration (Paulis Reference Paulis1984: LV–LVII), e.g. pagu bella [ˈpaɣu ˈbːɛlla] ‘not very beautiful’ (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Spectrogram of meda [ˈmɛða] ‘much’.

Figure 5: Spectrogram of item pagu bella [ˈpaɣu ˈbːɛlla] ‘not very beautiful’.

While in other Campidanese varieties /t/ and /d/ are produced as [ð], in intervocalic environments, across word boundaries and within words respectively, in the Cagliari dialect in these contexts, they are more commonly realized as an alveolar tap [ɾ]. This sound represents a sociophonetic variant of both /t/ and /d/, e.g. meda ‘much’ in Cagliari can be realized as [ˈmɛða] (Figure 4) or as [ˈmɛɾa] (Figure 6); similarly, su topi ‘the mouse’ can be pronounced as [su ˈðɔpi] or [su ˈɾɔpi]. The alternation of these two variants, [ð] and [ɾ], depends on factors such as social class and communicative style. The stigmatized variant is the alveolar tap [ɾ], while the fricative variant [ð] is perceived as the standard variant.

Figure 6: Spectrogram of meda ‘much’ pronounced with an alveolar tap [ˈmɛɾa].

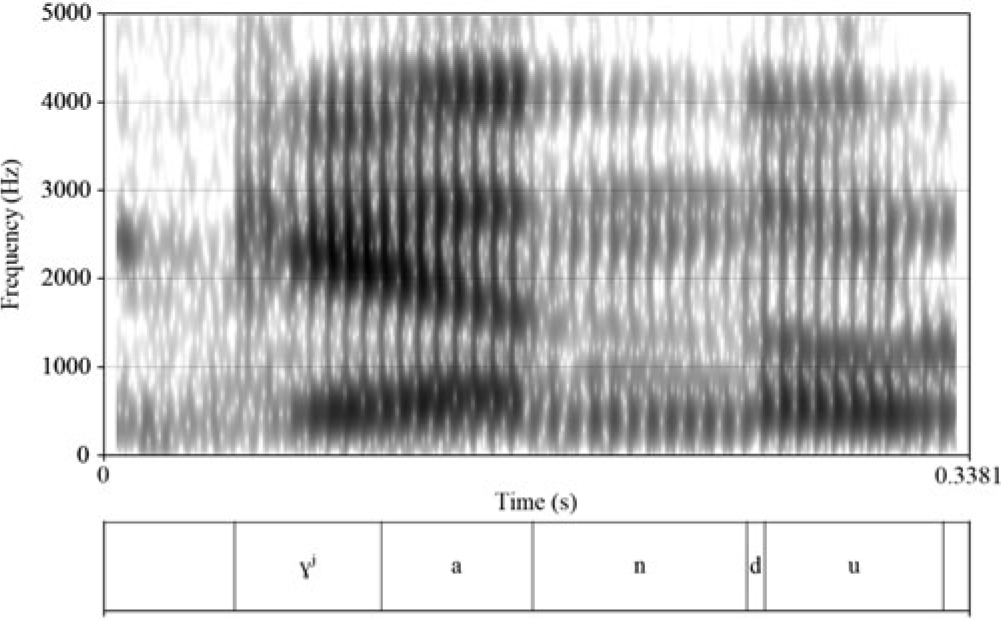

As for velar plosives, a specific feature of the Cagliari dialect, which is subject to sociophonetic variation, is the palatalization of the velar plosives /k ɡ/ preceding the open front vowel /a/, e.g. candu [ˈkjandu] ‘when’ (see also Virdis Reference Virdis and Paulis2013: 174). The palatalized variants represent a local stereotypes. Figures 7 and 8 illustrate a word containing a palatalized /k/ in front of /a/, and an example without it, respectively. Spectrograms show the productions of two words, candu ‘when’ and cantu ‘how much’. In the first instance the speaker produces [ˈɣjandu], while in the second, [ˈɣantu] – there is no palatalization.Footnote 2

Figure 7: Spectrogram of item candu [ˈɣjandu] ‘when’.

Figure 8: Spectrogram showing cantu [ˈɣantu] ‘how much’.

As seen in these two figures, the F2 after [ɣ] is much higher in the first word (2216 Hz) than the second (1754 Hz), and thus clearly indicative of a palatal onglide (see Ní Chiosáin & Padgett Reference Ní Chiosáin and Padgett2012).

In word-initial position,/s/ is realized as [s] if it is followed by a vowel or a voiceless consonant, e.g. soli [ˈsɔli] ‘sun’, sperai [speˈɾai] ‘to hope’, but it is produced as [z] preceding a voiced consonant, e.g. sballiai [zballiˈai] ‘to make a mistake’, as in Italian. This applies also within words, e.g. turismu [tuˈɾizmu] ‘tourism’. In pre-consonantal environments /s z/ are variably realized as [ʃ] depending on social factors, e.g. dd’at scopiada [ɖɖˈaɾiʃkoˈpːjaɾa] ‘s/he broke it’ (Figure 9), prus mannu [pruʃ ˈmannu] ‘bigger’ (Figure 10). The postalveolar realization [ʃ] represents a stigmatized variant, connected to low social class and very informal styles.

Figure 9: Spectrogram of dd’at scopiada [ɖɖ ˈaɾi ʃkoˈpːjaɾa] ‘s/he broke it’.

Figure 10: Spectrogram of prus mannu [pruʃ ˈmannu] ‘bigger’.

In intervocalic environments, we find /s/ realized as a voiced consonant as in standard Italian, e.g. arrosa [arˈrɔza] ‘rose’, su soli [su ˈzɔli] ‘the sun’; however, in Cagliari Sardinian in these environments the phonetic realization may also be [s], e.g. Nostra Sennora [ˈnɔstra sɛnˈnɔɾa] ‘Our Lady’ (see Pinto Reference Pinto and Paulis2013: 140).

The postalveolar affricate /ʧ/ is realized as [ʒ] across word boundaries, between vowels, e.g. custu certu [ˈɣustu ˈʒertu] ‘this fight’ (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Spectrogram of item custu certu [ˈɣustu ˈʒertu] ‘this fight’.

In this same environment, the labiodental fricative /f/ is produced as [v], e.g. su fradi [su ˈvraði] ‘the brother’.

From the description presented so far, the existence of a pattern of lenition affecting the voiceless plosives /p t k/, the voiceless postalveolar affricate /ʧ/ and the voiceless fricatives /s f/ emerges: in intervocalic position, across word boundaries, /p t k/ and /ʧ/ undergo spirantization and voicing, while /s f/ turn into [z v]. In the same context, /b d ɡ/ are generally produced with a long duration, but they spirantize in word-medial position. However, in external sandhi, when the word preceding the initial voiceless obstruent is a word historically ending with a consonant, lenition is blocked and the obstruent is produced with a long duration (as in the case of word-medial intervocalic position) although the context is apparently intervocalic, e.g. de terra < DE TERRA [de ˈðɛrra] ‘of soil’, but a terra < AD TERRA(M) [a ˈtːɛrra] ‘to the ground’ (see Virdis Reference Virdis1978), iat fatu [ˈia ˈfːatːu] ‘s/he had done’, nciat postu [ʧ a ˈpːostu] ‘s/he has put’ (Figure 12). These are cases of ‘postlexical gemination’ (Ladd Scobbie Reference Ladd, Scobbie, Local, Ogden and Temple2003: 169) This particular process of gemination is not restricted to obstruents but it occurs also with sonorants, e.g. si podiat nai [ˈzi βɔˈɾia ˈnːai]Footnote 3 ‘you could say’.

Figure 12: Spectrogram of item nci at postu [ʧ a ˈppostu] ‘s/he has put’.

The retroflex plosive /ɖ/ appears only in geminate form, e.g. moddi [ˈmɔːːi] ‘soft’ (Figure 13), and only a few minimal pairs with /d/ can be found, e.g. ddus [ɖɖus] ‘them’ ∼ duus [dus] ‘two’, sedda [ˈsɛɖɖa] ‘saddle’ ∼ seda [ˈsɛða] ‘silk’. /ɖ/ is often pronounced as an alveolar plosive [dd].

Figure 13: Spectrogram of item moddi [mɔɖɖi] ‘soft’.

Sonorants

The nasal /n/has labiodental and velar allophones, e.g. cunfradia [kmɱfraˈðia] ‘confraternity’, conca [ˈkɔŋka] ‘head’, following the tendency to nasal homorganicity.

As for the Cagliari lateral approximant /l/, this phoneme has a velar allophone [ɫ], in intervocalic and preconsonantal environments, e.g. dificili [diˈfiʧiɫi] ‘difficult’.

Intervocalic singleton /r/ is always realized as [ɾ], e.g. pira [ˈpiɾa] ‘pear’. In all other contexts it is realized as a trill [r], e.g. traballai [trabːalˈlai] ‘to work’, rispetu [risˈpetːu] ‘respect’. Therefore, the alveolar tap [ɾ] is an allophone of /r/ (in word-medial intervocalic position) in all Campidanese varieties and in the Cagliari dialect it is also a sociophonetic variant of /t/ and /d/, as mentioned before. Consequently, a word like maridu [maˈɾiðu] ‘husband’ in the Cagliari dialect can be realized also as [maˈɾiɾu], with the first [ɾ] representing /r/ and the second, /d/.

Geminates

As already mentioned, in specific contexts, the obstruents are subject to lengthening but these long segments do not phonologically contrast with their singleton counterparts because of historical and synchronic processes of lenition. In Cagliari Sardinian, the phonemic opposition between geminate and non-geminate consonants is limited to the consonants /n l r/, e.g. manu /ˈmanu/ ‘hand’ ∼ mannu /ˈmannu/ ‘big’, filu /ˈfilu/ ‘thread’ ∼ fillu /ˈfillu/ ‘son’, caru /ˈkaɾu/ ‘dear’ ∼ carru /ˈkarru/ ‘wagon’. This can be contrasted with the Italian system, which has 15 contrastive geminate consonants (Bertinetto & Loporcaro Reference Bertinetto and Loporcaro2005).

Vowels and diphthongs

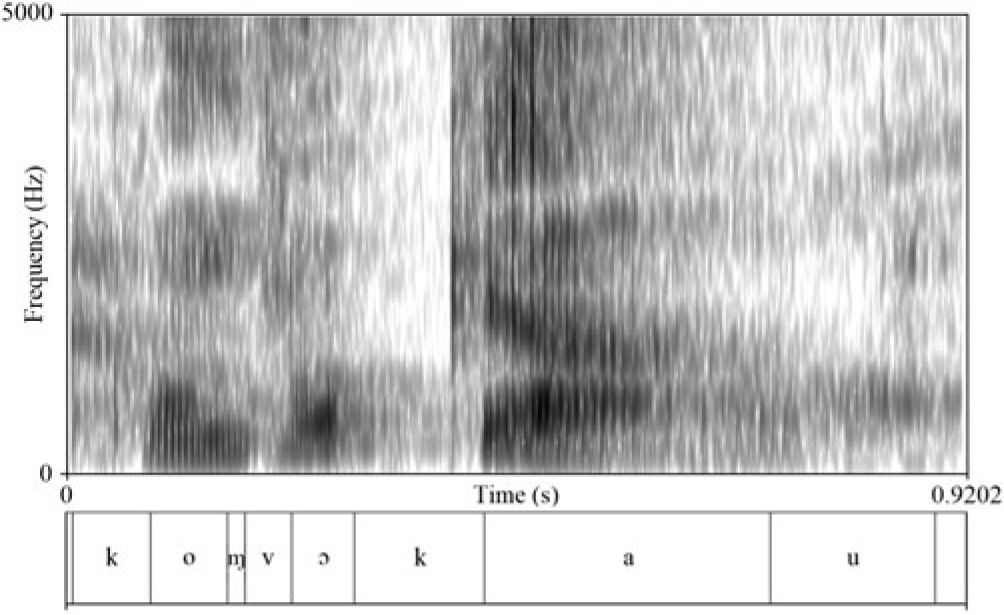

Cagliari Sardinian, like all Campidanese varieties, has a surface inventory of seven vowels in stressed position: [i e ɛ a ɔ o u]. Figure 14 shows formant values for the seven vowels of the Cagliari Sardinian system [i e ɛ a ɔ o u]. Values are extracted from the speech of a male consultant (VM46).

Figure 14: F1*F2 vowel chart for Cagliari Sardinian.

The distribution of mid vowels is predictable because high-mid vowels appear only before final unstressed high vowels. Low-mid vowels /ɛ ɔ/ alternate with /e o/, respectively, if followed by a phonetically high vowel. This is therefore a process of vowel harmony, known in Romance linguistics as metaphony, e.g. bella [ˈbɛlla] ‘beautiful (f)’, bellu [ˈbellu] ‘beautiful (m)’; cosa [ˈkɔza] ‘thing’ and logu [ˈloɣu] ‘place’. Given that high-mid vowels derive from low-mid vowels, according to Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998), Frigeni (Reference Frigeni2002) and Torres-Tamarit, Linke & Vanrell (Reference Torres-Tamarit, Linke and del Mar Vanrell2017), high-mid vowels are considered allophones of low-mid vowels. Therefore, the contrastive vowel inventory of all Campidanese varieties, including Cagliari Sardinian, has only five vowels, /i ɛ a ɔ u/. Metaphony in Campidanese is blocked in two cases (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998, Frigeni Reference Frigeni2002, Torres-Tamarit et al. Reference Torres-Tamarit, Linke and del Mar Vanrell2017):****************************************

-

It is also possible to find [ɛ c] before high vowels in inflectional suffixes when final /i u/ are developments of Latin E and O. It is important to bear in mind that in the suffixal domain, Campidanese Sardinian has a surface three-vowel system [i a u]. However, historical and inter-dialectal data prove that the subset of inflectional suffixes which do not trigger metaphony can be considered as derived high vowels, given that they are the result of a process of vowel merger in the suffixal domain which has led phonemic mid vowels to merge on the surface with high vowel suffixes (Frigeni Reference Frigeni2002, Torres-Tamarit et al. Reference Torres-Tamarit, Linke and del Mar Vanrell2017). In view of this, we have, for example, [ˈfrɔɾi] < FLORE(M) ‘flower’, [ˈbɛni] < BENE ‘well’. This produces some minimal pairs, e.g. [ˈbeni] < VENI ‘come (imperative form)’, [ˈbɛni] < BENE ‘well’; [ˈollu] < OLEUM ‘oil’, [ˈɔllu] < *VOLEO ‘I want’.

-

Metaphony is also blocked when it interacts with a process of word-final vowel epithesis, which applies in two distinct environments (Paulis Reference Paulis1984: XXIV–XXV):

-

(i) After stressed vowels in word-final position as a means to prevent words with final stress, e.g. caffè [kaˈfːɛi] ‘coffee’, però [pɛˈɾɔu] ‘but’.

-

(ii) After a final consonant, to prevent a consonant in word-final coda position, e.g. ses [ˈsɛzi] ‘you are’. This is called ‘paragogic vowel’, generally characterized by the same quality as that of the preceding vowel. However, in Campidanese Sardinian it can be different, as shown in ses [ˈsɛzi] ‘you are’; in particular, if the preceding lexical vowel is /e/ or /i/, the paragogic vowel is a high front vowel while if the preceding vowel is /o/ or /u/, it is a high back vowel. Therefore, the paragogic vowel copies the degree of backness of the preceding vowel (Torres-Tamarit et al. Reference Torres-Tamarit, Linke and del Mar Vanrell2017: 5).

-

With regard to unstressed vowels in word-final syllables, the vowel system reduces to three vowels /a i u/ (Virdis Reference Virdis1978), e.g. froris [ˈfrɔɾis] < FRORES ‘flowers’, boxi [ˈbcʒi] < VOCE(M) ‘voice’; castiai [kastiˈai] < CASTICARE ‘to look’; bonus [ˈbɔnus] < BONOS ‘good (pl)’, logu [ˈloɣu] < LOCU(M) ‘place’;.

In non-word-final post-tonic and pretonic positions, all seven vowels can be found, e.g. àxina [ˈaʒina] ‘grapes’, gèneru [ˈʤeneru] ‘son-in-law’, telèfonu [tɛˈlɛfɔnu] ‘telephone’, gùturu [ˈɡutːuɾu] ‘throat’, cenàbara [ʧɛˈnaβaɾa] ‘Friday’; maridu [maˈɾiðu] ‘husband’, genugu [ʤeˈnuɣu] ‘knee’, conillu [koˈnillu] ‘rabbit’, sitzigorru [sittsiˈɣorru] ‘snail’, mulleri [mulˈlɛri] ‘wife’.

Diphthongs are formed by a sequence of a glide /w/ or /j/ and a vowel. There are both rising and falling diphthongs (symbols for approximants are used only for rising diphthongs).

However, diphthongs, especially raising diphthongs, can undergo the so-called ‘secondary hiatus’, a process of syllabification, defined as the modification of a diphthong into a disyllabic sequence (see Loi Corvetto Reference Loi1979–1980, Reference Loi1983: 60–70; Virdis Reference Virdis and Paulis2013: 179; for other Romance varieties, see Chitoran & Hualde Reference Chitoran and Hualde2007). For example, the word italianu ‘Italian’ is pronounced as [itːaliˈanu] and not as [itːaˈljanu]; the word cuindixi ‘fifteen’ is pronounced as [kuˈindiʒi] and not as [ˈkwindiʒi]. Figures 15 and 16 display two different tokens, bianca ‘white (f)’ and biancu ‘white (m)’, respectively, produced by the same speaker (CF73): [biˈaŋka] with the hiatus and [ˈbjaŋku], with the diphthong.

Figure 15: CF73 saying bianca [biˈaŋka] ‘white (f)’.

Figure 16: Spectrogram of biancu [ˈbjaŋku] ‘white (m)’.

Even without taking the measurements of the acoustic parameters, by comparing the spectrograms in these two figures, the difference between the trajectories of the first two formants in the hiatus and the trajectories in the diphthong becomes clear.

Stress

Drawing on Porru’s dictionary (Porru Reference Porru1832), Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998) reports that 85% of underived words show stress in the penultimate syllable, e.g. pratza [ˈprattsa] ‘town square’, traballu [traˈbːallu] ‘work, job’, ventana [vɛnˈtana] ‘window’. Fourteen per cent of words are stressed on the antepenultimate syllable, e.g. àxina [ˈaʒina] ‘grapes’, cenàbara [ʧɛˈnaβaɾa] ‘Friday’, while 1% show final stress. Nouns with final stress tend to be repaired by means of epithesis, e.g. caffé [kaˈfːɛi] ‘coffee’, però [peˈiɔu] ‘but’ (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 65). Word-stress assignment can be distinctive, given the presence of minimal pairs such as cantat [ˈkantaða] ‘s/he sings’ vs. cantat [kanˈtaða] ‘s/he sang’ (see Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998, Vanrell et al. Reference Vanrell, Ballone, Schirru, Prieto, Frota and Prieto2015).

Transcription of recorded passage ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

Phonemic transcription

su ˈbentu e tramunˈtana e su ˈsɔli ˈfiant abetiˈendi aˈpittsus e ˈkini ˈfessit su prus ˈfɔrti | ˈkandu ˈɛst arriˈbau ˈunu vjadʤaˈdɔri imbusˈsau in ˈdunu manˈteɖɖu || ˈissus ant detˈtsidju ka suˈprimu ki ˈfessit arrenˈneʃʃu a ˈfai boˈɡai su manˈteɖɖu a su vjadʤaˈdɔri | ˈiat ˈɛssi ˈstetju prus ˈfɔrti de s ˈatru || dunkas su ˈbentu e tramunˈtana at sulˈlau prus ˈfɔrti ki poˈdiat | ma prus ˈissu sulˈlada | prus su vjadʤaˈ dɔri si imbusˈsada in su manˈteɖɖu | e a sa ˈfini su bent e tramunˈtana at arrinunˈʧau || inˈtsandus su ˈsɔli ɖɖ at kallenˈtau ˈfendi ˈluʒi | e ˈtotu in ˈduna ˈbɔrta su vjadʤaˈdɔri si nd ɛst boˈɡau su manˈteɖɖu || e aˈiʧi su bent e tramunˈtana atˈdepju aˈmiti ka de is dus suˈsɔli ˈfiat su prus ˈfɔrti||

Phonetic transcription

su ˈbːentu e ðramunˈtana e su ˈzɔli ˈvianta abːetːiˈendi aˈpːittsuzu e ˈkːini ˈvessi su βruˈfːɔrti | ˈkandu ˈɛst arriˈbːau ˈunu vjadʤaˈɾɔɾi imbusˈsau in ˈdunu manˈteɖɖu || ˈissuzu ˈanti detˈtsiɾju ɣa su ˈβrimu ɣi ˈvessiɾi arrenˈneʃʃu a ˈfːai bːoˈɣai su manˈteɖɖu a su vjadʤaˈɾɔɾi | ˈiaɾˈɛssi ˈstetːju βru ˈfːɔrti de s ˈatru || ˈduŋkaza su ˈbːentu e ðramunˈtana a sulˈlau βru ˈfːɔrti ki βoˈɾiaɾa | ma ˈβruzu ˈissu sulˈlaɾa || pru su vjadʤaˈɾɔɾi si imbusˈsaɾa in su manˈteɖɖu | e a sa ˈvini su ˈbːent e ðramunˈtana ˈaɾi arrinunˈʧau || in ˈtsanduzu su ˈzɔli ɖɖa kːallenˈtau ˈvendi ˈluʒi | e ˈtːotu in ˈduna ˈbːɔrta su vjadʤaˈɾɔɾi si nd ɛbːoˈɣau su manˈteɖɖu || e aˈiʧi su ˈbːent e ðramunˈtana a ˈdːepju aˈmitːi ka de iz ˈduzu su ˈzɔli ˈvia su βru ˈfːɔrti ||

Orthographic version

Su bentu de tramuntana e su soli fiant abetiendi apitzus de chini fessit su prus forti candu est arribau unu viagiadori imbussau in d-unu manteddu. Issus ant detzìdiu ca su primu chi fessit arrennèsciu a fai bogai su manteddu a su viagiadori iat a essi stètiu prus forti de s’atru. Duncas, su bentu de tramuntana at sullau prus forti chi podiat, ma prus issu sullat prus su viagiadori si imbussat in su manteddu; e a sa fini su bentu de tramuntana at arrinunciau. Intzandus su soli dd’at callentau fendi luxi e, totu in d-una borta, su viagiadori si ndi est bogau su manteddu. E aici su bentu de tramuntana at dèpiu amìti ca de is duus su soli fiat su prus forti.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the Cagliari Sardinian speakers who participated in this study. I would like to thank Paul Foulkes, Alessandro Vietti, Amalia Arvaniti, Ewa Jaworska and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to Pierluigi Cuzzolin and Ignazio Efisio Putzu for useful suggestions on some parts of this work. All errors and omissions are entirely my responsibility.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100318000385.