Introduction

Five of the seven extant species of sea turtles use the Brazilian coast for reproduction and foraging: loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), green turtle (Chelonia mydas), leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), and olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) (Marcovaldi and Marcovaldi, Reference Marcovaldi and Marcovaldi1999). These are all cosmopolitan species that are generally found in tropical and subtropical seas (Márquez, Reference Márquez1990); many are threatened in different degrees both internationally (IUCN, 2023) and in Brazil (ICMBIO, 2018) due to intense historical exploitation and environmental pressures (Marcovaldi et al., Reference Marcovaldi, Thomé, Sales, Coelho, Gallo and Bellini2002; Goldberg and Reis, Reference Goldberg, Reis, Reis and Curbelo-Fernandez2017). The major threats in recent decades include loss or degradation of habitats (Bugoni et al., Reference Bugoni, Krause and Petry2001; Corcoran et al., Reference Corcoran, Biesinger and Grifi2009; Colman et al., Reference Colman, Lara, Bennie, Broderick, Freitas, Marcondes, Witt and Godley2020), incidental capture in fishing gear (Hays et al., Reference Hays, Broderick, Godley, Luschi and Nichols2003; Kotas et al., Reference Kotas, Santos, Azevedo, Gallo and Barata2004; Marcovaldi et al., Reference Marcovaldi, Sales, Thomé, da Silva, Gallo, Lima, Lima and Bellini2006), ingestion of solid waste (Mrosovsky et al., Reference Mrosovsky, Ryan and James2009; Schuyler et al., Reference Schuyler, Hardesty, Wilcox and Townsend2013), climate change (Chaloupka et al., Reference Chaloupka, Kamezaki and Limpus2008), and the occurrence of pathologic agents (Aguirre et al., Reference Aguirre, Balazs, Zimmerman and Spraker1994; Harvell et al., Reference Harvell, Kim, Burkholder, Colwell, Epstein, Grimes, Hofmann, Lipp, Osterhaus, Overstreet, Porter, Smith and Vasta1999; Manire et al., Reference Manire, Stacy, Kinsel, Daniel, Anderson and Wellehan and2008).

Besides these factors, Hackradt (Reference Hackradt2005) reported that the predation of nests and hatchlings by wild and domestic animals constitutes a threat to the conservation of sea turtles. For adult females, nesting is the time of greatest vulnerability, as the animals lose their agility and become slower when out of the water, rendering them defenceless and completely exposed to attacks from predators (Lobato, Reference Lobato2019). There are few studies describing attacks by canids on sea turtles along the Brazilian coast. Nonetheless, Santos and Godfrey (Reference Santos and Godfrey2001) reported this type of impact, with domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), attacking loggerhead and hawksbill sea turtles at the time of nesting. Hackradt (Reference Hackradt2005) also reported the predation of nests and hatchlings by Cerdocyon thous (Canidae) and C. l. familiaris on beaches of the state of Sergipe in northeast Brazil. In other countries, the impact of domestic and wild animals has also been reported on sea turtles (Margaritoulis et al., Reference Margaritoulis, Theodorou, Tsaros and Nestoridou2019; Rojas-Cañizales et al., Reference Rojas-Cañizales, Mejías-Balsalobre, Naranjo and Arauz2022), considering various land predators such as jackals (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Verhoeven, Van Piggelen and Strijbosch1994), jaguars (Alfaro et al., Reference Alfaro, Montalvo, Guimaraes, Saenz, Cruz, Morazan and Carrilo2016; Escobar-Lasso et al., Reference Escobar-Lasso, Gil-Fernández, Sáenz, Carrilo-Jiménez, Wong, Fonseca and Gómez-Hoyos2017), and coyotes (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Behm, Hagerty, Mayour, Goldenberg and Spotila2003). Considering the scarcity of information on this topic, the aim of the present study was to report events of canid attacks on sea turtles in northeastern Brazil to assist in the establishment of possible prevention and emergency measures for the conservation of chelonians.

Materials and methods

Study area

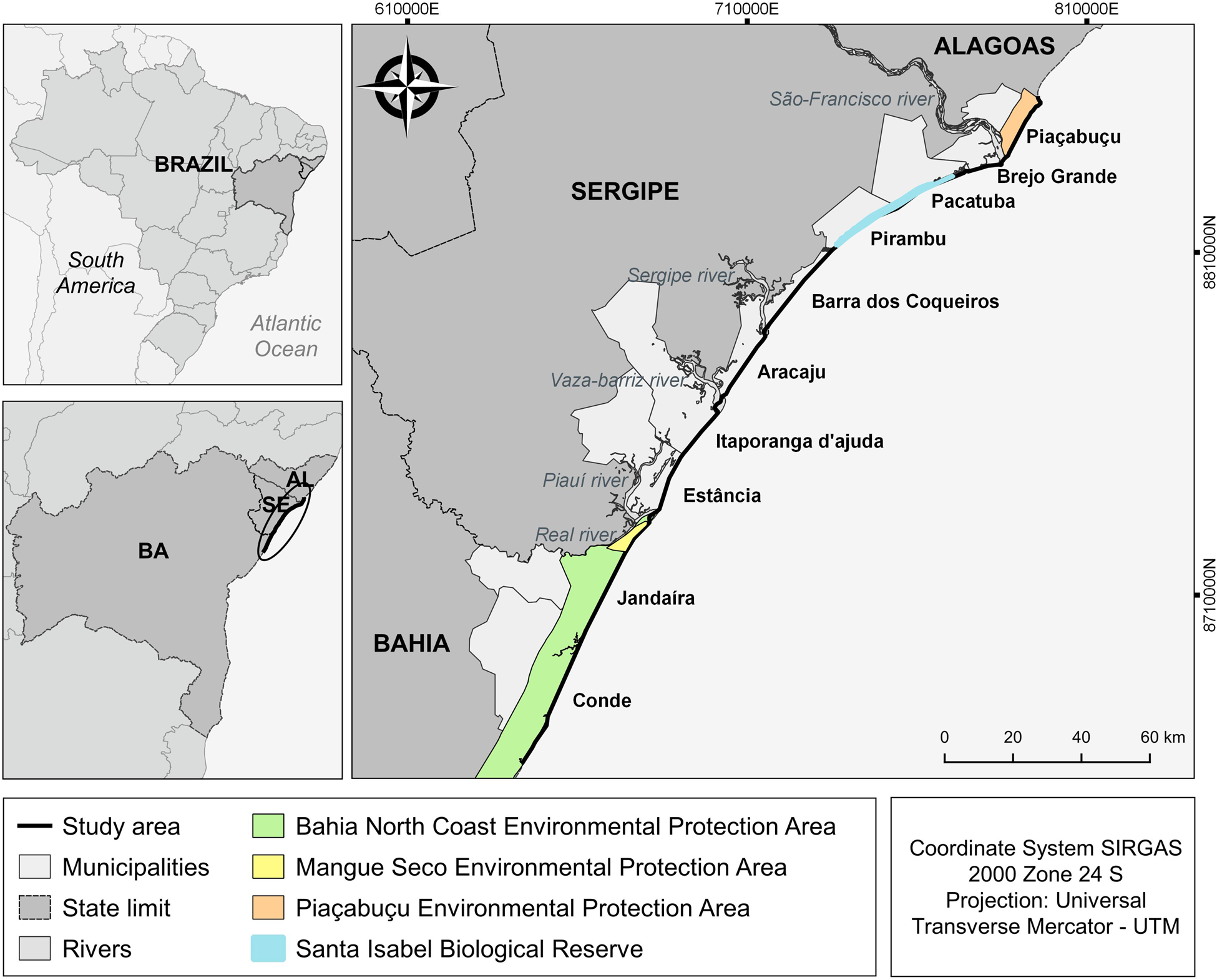

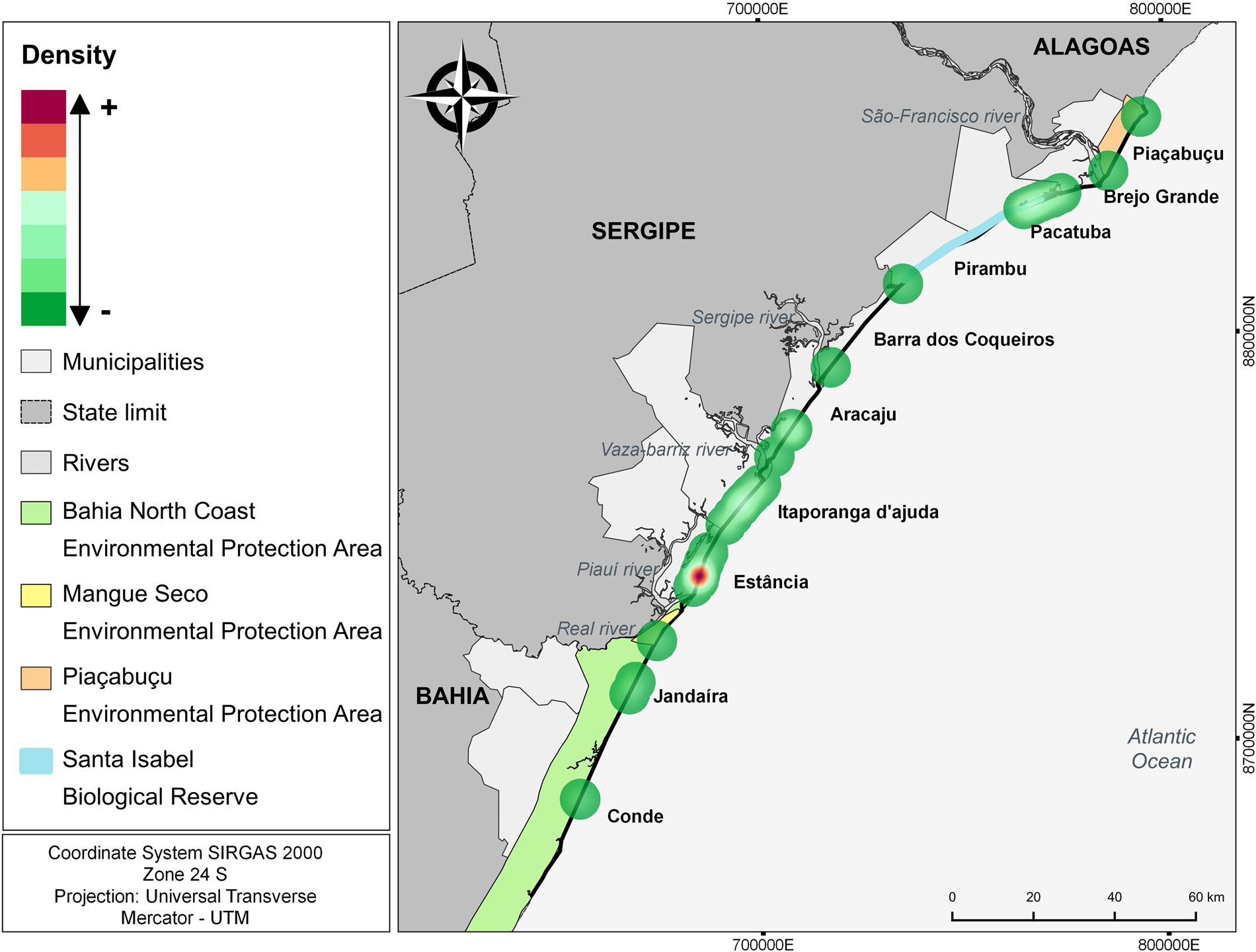

The study was conducted along the Sergipe-Alagoas Basin coastline, northeastern Brazil, extending 254 km from the municipality of Piaçabuçu in southern Alagoas state to the municipality of Conde in northern Bahia state (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study area in the states of Alagoas, Sergipe, and Bahia, Northeastern Brazil.

In Alagoas, the study area was within the limits of the Piaçabuçu Environmental Protected Area, extending over 23 km of beaches between Pontal do Peba and the mouth of the São Francisco River. In Sergipe, the study area comprised the entire coastline, extending 163 km (Santos and Vilar, Reference Santos and Vilar2012). The Santa Isabel Biological Reserve is situated in the northeastern portion of this stretch, which is home to the largest reproductive site of L. olivacea in Brazil. The reserve encompasses two municipalities – Pirambu and Pacatuba, located 35 and 70 km respectively from the capital Aracaju, which has the most urbanized stretch along the coast of Sergipe (Oliveira and Landim, Reference Oliveira and Landim2014). The study area in the state of Bahia corresponded to the municipalities of Jandaíra and Conde, which is a region with striking touristic potential and home to the Mangue Seco Environmental Protected Area and the Northern Coast of Bahia Environmental Protected Area.

Rescue, clinical evaluation and necropsy

Between March 2010 and October 2019, records were made of stranded sea turtles – injured or dead – found on beaches during active searches (regular monitoring) or through notifications from collaborators due to efforts developed by the Regional Monitoring Program of Strandings and Abnormalities in the Sergipe-Alagoas Basin (Reis et al., Reference Reis, Carneiro, Moreira, de Almeida, Borges, Parente, Reis and Carneiro2019). Monitors travelled the entire length (254 Km – nesting beaches) of the area on a daily basis with the aid of motorcycles during the first low tide. Additional stranding events were reported by local residents, tourists and fishermen (Reis et al., Reference Reis, Carneiro, Moreira, de Almeida, Borges, Parente, Reis and Carneiro2019). Upon receiving news of a stranded turtle reported by the monitoring team or collaborators, a rescue team composed of veterinarians, biologists, and environmental technicians performed the initial clinical care or necroscopic examination (Reis et al., Reference Reis, Carneiro, Moreira, de Almeida, Borges, Parente, Reis and Carneiro2019). The condition of the specimen was determined using a classification system adapted from Geraci and Lounsbury (Reference Geraci and Lounsbury2005) and Monteiro et al. (Reference Monteiro, Estima, Gandra, Silva, Bugoni, Swimmer, Seminoff and Secchi2016): Code 1 – live animal, Code 2 – recent death, Code 3 – moderate decomposition, Code 4 – advanced decomposition, Code 5 – mummified or dried bones.

Injured-stranded sea turtles were rescued and sent to the Rehabilitation and Oil Removal Center of the Fundação Mamíferos Aquáticos [Aquatic Mammal Foundation] for a clinical evaluation. Whenever possible, sea turtles found dead, or that died during the rehabilitation process, were submitted for necropsy by a Veterinary team for cause of death determination and/or identification of any significant pathological lesions. During the necropsy the following information was recorded for each stranded animal: species (Márquez, Reference Márquez1990), age class, sex (Wyneken, Reference Wyneken2001), condition code, date and location of stranding, and overall body condition (Poor, Fair, Good) (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Burkholder, Heithaus and Dill2009). Injuries caused by canids and other external signs were carefully evaluated and photographed to assist in the necropsy report. The maturation stage of the specimens was assigned based on the standard measure of curved carapace length (CCL) (Eckert et al., Reference Eckert, Bjorndal, Abreu-Grobois and Donnelly1999). Sea turtles with CCL greater than 83 cm for loggerhead turtles, 90 cm for green turtles (Almeida et al., Reference Almeida, Moreira, Bruno, Thomé, Martins, Bolten and Bjorndal2011) and 63 cm for olive ridley turtles were considered adults (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007). The characterization of domestic dog attacks on sea turtles was based on the registration of dogs nearby or by visualization of paw prints in the sand around the injured turtle.

Data analysis

Statistical tests were performed to evaluate the difference between sex, species, months, municipalities and years. For all tests, the different numbers of attack by years were used as replication, except for the test between the years, where the numbers of attack by months were used. The normality of all data (except sex) was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The difference in the number of predation events between sex was calculated using the chi-square test; animals of undetermined sex were not included. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate differences in the number of events among species, months of the year and locations. When a significance level was met, the Mann–Whitney post-hoc test was used to identify pairwise differences.

The geographic coordinates of attack locations were analysed using kernel density estimation (Silverman, Reference Silverman1998; QGIS, 2020) with a 5 km radius to identify locations with the greatest density of events. Statistical analyses were conducted in the Past software (Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001), adopting a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05) for all analyses.

Results

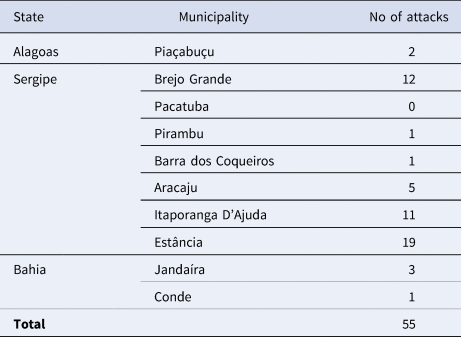

During the study period, 9841 sea turtle stranding events were recorded: 206 (2.09%) loggerhead individuals, 4178 (42.45%) green, 2 (0.02%) leatherback, 123 (1.24%) hawksbill, 5267 (53.52%) olive ridley, and 65 (0.66%) unidentified. Among these species, 55 (0.55%) suffered attacks by domestic dogs and other canid species during nesting or after becoming stranded (Table 1). Most of the attacked sea turtles were found dead (n = 38; 69.09%): 24 were classified as Code 2, seven as Code 3, and seven as Code 4. Animals encountered alive (n = 17; 30.91%) were taken to the Rehabilitation Center of the Aquatic Mammal Foundation but subsequently died due to the severity of the injuries.

Table 1. Number of attacks by domestic dogs or other canid species during nesting or after becoming stranded

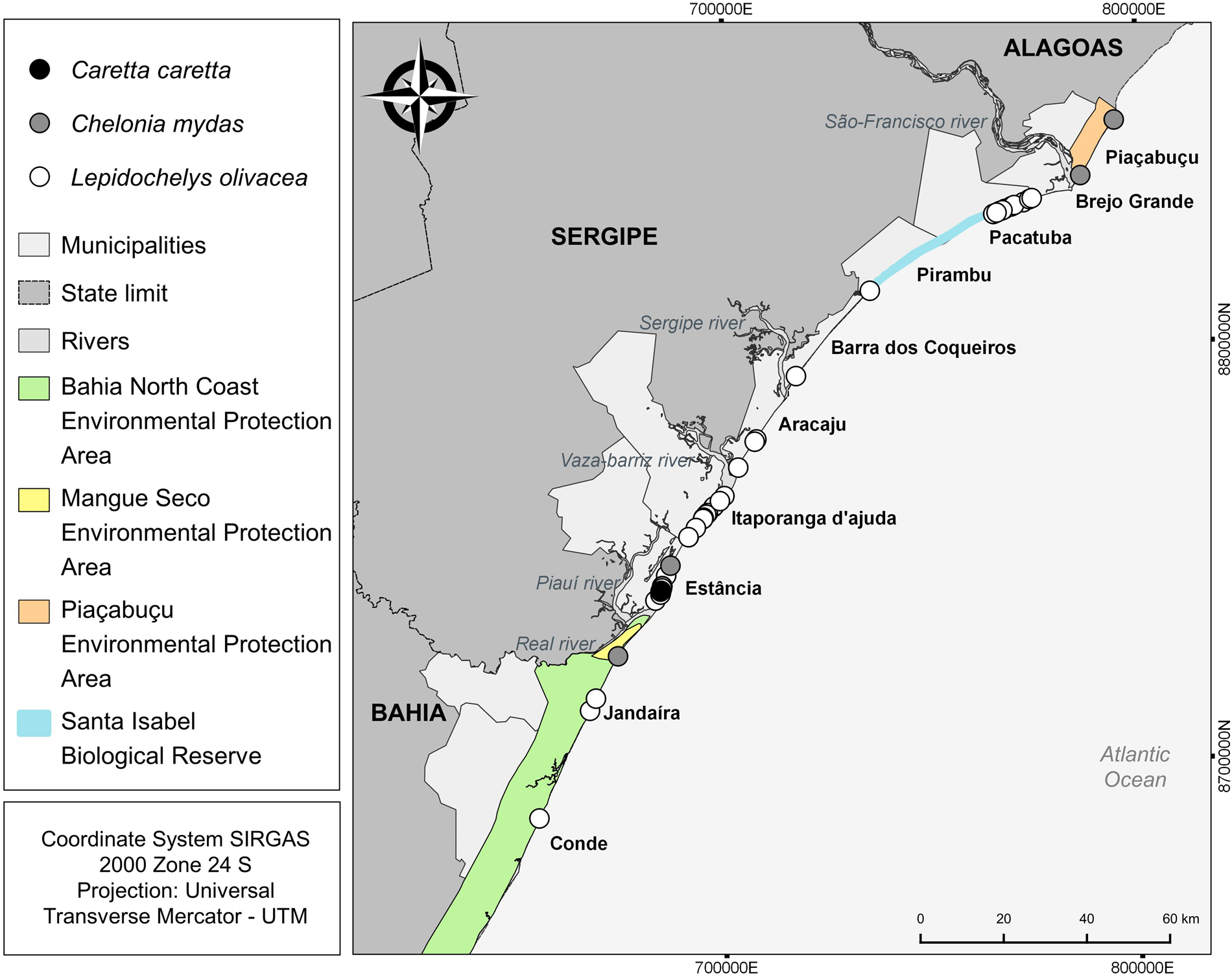

A significant difference (H: 7.21; p = 0.008) was found among the species of sea turtle attacked, with the greatest number of events involving olive ridley (n = 50; 90.90%). Other occurrences involved green (n = 4; 7.27%) and loggerhead (n = 1; 1.81%) sea turtles.

The vast majority of attacks involved females (n = 50; 90.90%), with only one male specimen being attacked (n = 1; 1.81%) (Χ 2: 47.078; p < 0.0001). It was not possible to identify the sex of four sea turtles. Most attacked sea turtles were adult females with eggs in the coelomic cavity (n = 43; 86%). In many of these events, the presence of tracks and nests ready for laying were observed (Figure 2). The identification of ‘half-moon tracks’ suggests that the female travelled up and down the beach without performing any nesting. Records involved four juveniles of undetermined sex and one juvenile male. The latter stranded due to pathological disorders resulting from the ingestion of waste and was subsequently attacked by canids as determined by necroscopic examination.

Figure 2. Records of attacks by domestic or other canid species during nesting of after becoming stranded by sea turtle: (A and B) Attacked sea turtle females with eggs in the coelomic cavity; (C) Tracks of attacked females; (D) Nests of sea turtles finished prior to attacks by canids.

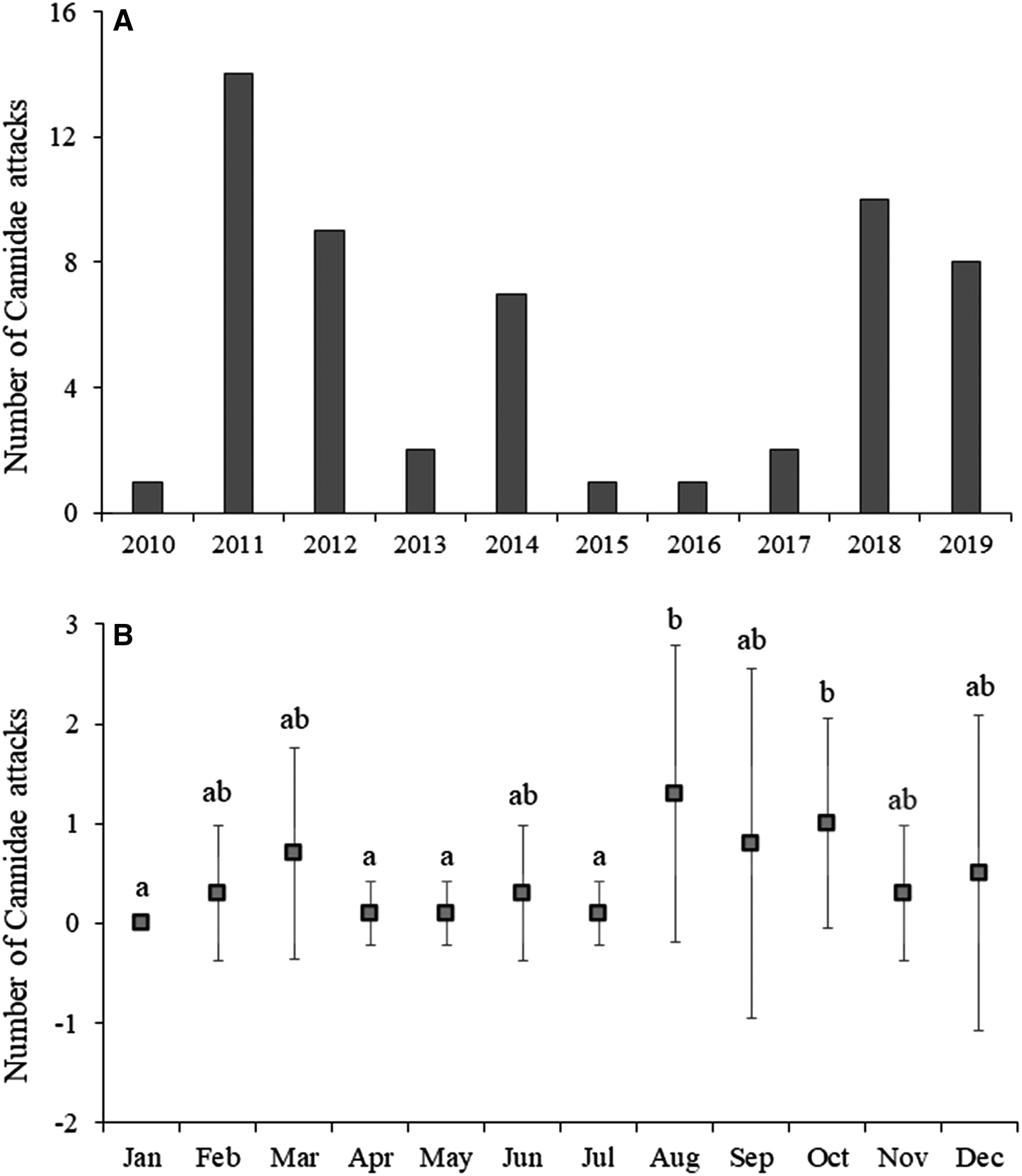

No significant difference was found among the years of the study, with a greater number of events in 2011, 2012, 2018, and 2019. Additionally, significant difference (H: 12.84; p = 0.015) was found among the month of the year (Figure 3).

Figure 3. (A) Number of attacks by canids on sea turtle from 2010 to 2019; (B) Mean and standard deviation of attacks by month of the year.

The number of attacks in the municipality of Estância in Sergipe (n = 19; 34,5%) was significantly higher (H: 11.37; p = 0.01) compared to all other municipalities with events (Table 2; Figure 4). Itaporanga D'Ajuda and Brejo Grande, also in Sergipe, there was a high number of predation events compared to other municipalities, but the differences were not statistically significant. Kernel analysis identified areas of greater density of attacks (Figure 5).

Table 2. Location and number of canid attacks on sea turtles

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of records of attacks by canids on sea turtles in states of Alagoas, Sergipe, and Bahia.

Figure 5. Kernel analysis identifying areas of greater density of attacks by canids on sea turtles.

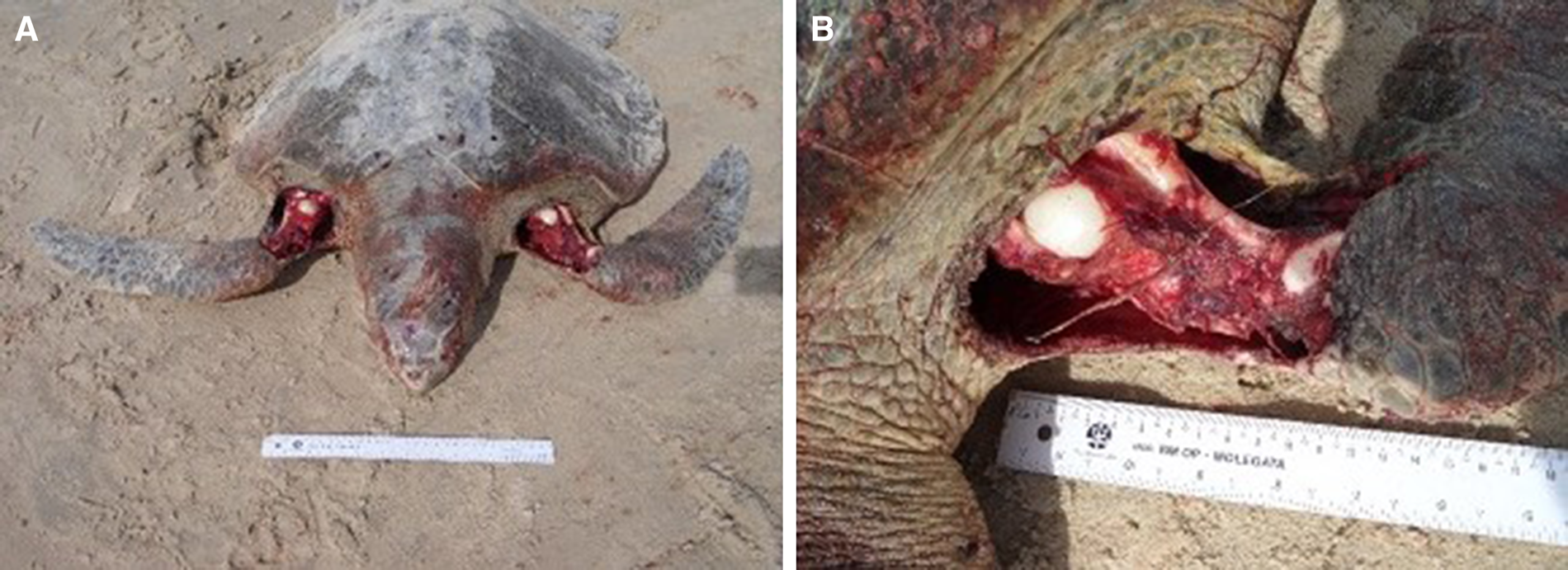

The attacked sea turtles had a good body condition and were clinically healthy. Most were in the egg-laying reproductive stage. The macroscopic injuries were similar on all animals, with the front flippers affected most: unilateral or bilateral lacerations, perforations and rupture of muscle fibres, ranging from superficial to deep; considerable loss of musculature compromising the brachial plexus; rupture of large blood vessels; and, in some cases, exposure of the humerus or oesophagus (Figure 6). The musculature and abdominal organs were moderately pale and anaemic. Injuries to the carapace and cranium, with scratch marks, were observed in some individuals (Figure 7), associated with blood stains on the sand. Only in the case involving the rescued male, the animal was underweight and associated clinical and pathological manifestations. The mortality rate in these events was 100% and the cause of deaths was hypovolemic shock due to the acute intense haemorrhaging caused by the bites.

Figure 6. (A) Bilateral lacerations of the front flippers with perforations and rupture of muscle fibres caused by bites from canids; (B) Considerable loss of musculature compromising the brachial plexus, rupture of large blood vessels, and exposure of the humerus.

Figure 7. (A and B) Lesions observed in the head and neck region of sea turtles attacked by canids. (C) Scratch marks to the carapace and cranium were observed in some individuals.

Discussion

The frequency of attacks by dogs and other canids on sea turtles was determined in the present study through a ten-year time series with robust data collected during the daily monitoring of the beaches. The results raise an alert regarding the potential of these events as a threat in some regions, especially because they are endangered species and females during nesting or with eggs in the coelomic cavity. The identification of predators is paramount for the establishment of management measures, especially in areas with anthropogenic impacts where the food web has been altered (Bellini and Sanches, Reference Bellini and Sanches1996). In some events reported, domestic dogs were caught in the act of preying upon sea turtles. Hackradt (Reference Hackradt2005) identified the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) predating nests in previous studies conducted in the same area, suggesting this species may be a potential aggressor in the attacked sea turtles reported here.

Even though turtle nest predation by canids has been widely documented (Bellini and Sanches, Reference Bellini and Sanches1996; Kurz et al., Reference Kurz, Straley and Degregorio2011; Pheasey et al., Reference Pheasey, McCargar, Glinsky and Humphreys2018), attacks on females during the nesting period have only recently been reported, with cases involving loggerheads in Greece (Margaritoulis et al., Reference Margaritoulis, Theodorou, Tsaros and Nestoridou2019), olive ridleys in India (Sarlin and Heeralal, Reference Sarlin and Heeralal2021) and both hawksbill and loggerhead turtles on the coast of Brazil (Santos and Godfrey, Reference Santos and Godfrey2001). Besides dogs, other species of mammals have also been found attacking sea turtles, such as jaguars (Panthera onca) in Costa Rica (Alfaro et al., Reference Alfaro, Montalvo, Guimaraes, Saenz, Cruz, Morazan and Carrilo2016; Escobar-Lasso et al., Reference Escobar-Lasso, Gil-Fernández, Sáenz, Carrilo-Jiménez, Wong, Fonseca and Gómez-Hoyos2017) and Mediterranean monk seals (Monachus monachus) on Zakynthos Island in the Ionian Sea in Greece (Margaritoulis and Touliatou, Reference Margaritoulis and Touliatou S2011).

The greater frequency of attacks involving L. olivacea is due to the fact that this species uses the southern portion of Alagoas and the northern portion of Bahia as the main reproductive areas in Brazil, with the coast of Sergipe as the main nesting area in the South Atlantic (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007; Matos et al., Reference Matos, Silva, Castilhos, Weber, Soares and Vicente2012; de Castilhos et al., Reference De Castilhos, Giffoni, Medeiros, Santos, Tognin, da Silva, Oliveira, Fonseca, Weber, de Melo, de Abreu, Marcovaldi and Tiwari2022). In these areas, previous studies have revealed an increasing trend was observed in the estimated number of nests per nesting season: from 252 nests in 1991/1992 to 2606 in 2002/2003, an approximately 10-fold increase in 11 years (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007). Thus, the greater occurrence of this species in the region contributes to a greater likelihood of canid attacks in the study area. Although the number of strandings of green turtles was significant, it was not possible to identify the reasons related to the lower number of attacks recorded on this species, when compared to attacks on olive ridley. Even though there is a greater frequency of nesting of olive ridley in the region, the difference found in the frequency of attacks between the two species mentioned may draw attention to the opportunity in which the events occurred considering the presence of canids at the time or possible canids preferences.

The vast majority of attacks were on females, which periodically go onto the beaches to lay eggs and, therefore, are more exposed and vulnerable to canid attacks. This culminates not only in the death of the individual but also the interruption of the reproductive cycle of these sea turtles. According to Margaritoulis and Touliatou (Reference Margaritoulis and Touliatou S2011), continuous removal of reproductive females may have a severe impact on sea turtle population. The only male identified in the present study likely became stranded due to pathological manifestations (intestinal obstruction). As Baptistotte (Reference Baptistotte2010) describes, males spend their entire lifecycle at sea and only end up stranded on beaches due to incidental capture by fishing operations or infectious diseases (Marcovaldi et al., Reference Marcovaldi, Santos and Sales2011).

The variation in the number of attacks recorded over the years is not exclusively due to the relationship with the number of nesting area, which is increasing on the coast of Sergipe (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007; de Castilhos et al., Reference De Castilhos, Giffoni, Medeiros, Santos, Tognin, da Silva, Oliveira, Fonseca, Weber, de Melo, de Abreu, Marcovaldi and Tiwari2022). Probably, the presence of canids with behavioural habits of attacking sea turtle is a determining factor. Thus, when restricting dogs to their homes is established, it prevents free movement in nesting areas. Furthermore, the absence of other canids on certain occasions may be a result of the mortality of specimens or their movement to other regions. In relation to the numbers of attacks throughout the year, the greatest frequency of events was clearly associated with the nesting period, which generally takes place between September and March on beaches in continental Brazil (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007). However, the events that occurred in August may have been the result of an increase in shrimp trawlers close to the coast, considered a relevant factor in the strandings of live and dead sea turtles in the state of Sergipe (Da Silva et al., Reference Da Silva, de Castilhos, dos Santos, Brondízio and Bugoni2010), which is currently the main threat to adult breeding females in this region (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007).

The greatest number of sea turtle attacks by canids occurred in Estância in Sergipe. At the time of the study, information on the distribution of the number of nests was not available for public consultation. However, through the Aquatic Biota Monitoring Information System (SIMBA, in Portuguese) it was possible to access data from September 2022 to April 2023 and identify that in the Sergipe-Alagoas Basin, the largest number of nests was registered in the municipality of Estância. In addition to the greater number of nests, the dunes, mangroves and other coastal systems in this area are the target of economic interest and promote real estate development related to tourist enterprises, causing disorganized human occupation (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Mello and Carvalho2016). This often leads to the abandonment of domestic dogs and their frequent presence on these beaches in search of food. Similarly, Baptistotte (unpublished data) attributed the presence of natural and non-natural predators on beaches mainly due to the excessive urbanization of coastal areas. Therefore, the growing number of abandoned domestic animals and the destruction of natural habitats favour the presence of stray canids on beaches (Santos and Vilar, Reference Santos and Vilar2012). The large number of attacks in Brejo Grande may be explained by the fact that these areas have a high concentration of nesting females (Marcovaldi et al., Reference Marcovaldi, Lopez, Soares, Santos, Bellini and Barata2007; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Castilhos, Lopez and Barata2007; Matos et al., Reference Matos, Silva, Castilhos, Weber, Soares and Vicente2012) and by the presence of beach houses with domestic dogs. Aracaju (Sergipe's capital), is the more urbanized area with tourist sites and a large quantity of bars on the beaches, attracting the presence of dogs and increases the risk of attacks on sea turtles.

The injuries caused by canid attacks were responsible for the death of the affected sea turtles. Even in cases of sea turtles rescued alive, the prognosis was unfavourable and, despite all efforts during the rehabilitation process, euthanasia was often necessary due to the poor physical state of the patients. Injuries were similar to those described for loggerhead turtles attacked by dogs in Greece, with a predominance of lesions on the flippers and the removal of extensive fragments of muscle tissue exposing bone (Margaritoulis et al., Reference Margaritoulis, Theodorou, Tsaros and Nestoridou2019). Sarlin and Heeralal (Reference Sarlin and Heeralal2021) found even more extensive injuries to olive ridley sea turtles in India, with records of ventral laceration and complete evisceration.

Canid attacks on sea turtles have a negative impact and constitute yet another threat to the existence of these species in Brazil. Attacks on females in an active nesting stage directly threatens their reproductive cycle by hampering the laying of eggs and, therefore, preventing the hatching of hundreds of young turtles. The observation of predation by canids as a threat to sea turtles was possible due to the combination of long-term (10 years), systematic (active searches on a daily basis) monitoring, community participation and the dedicated veterinarians duly trained in postmortem evaluations of the affected animals. The identification of the causes of strandings is one of the main ways to learn about existing threats and the adoption of measures for the conservation of the species involved (Lima et al., Reference Lima, Lima, de Oliveira, Attademo and Silva2021).

All species of sea turtle affected are threatened to some degree and the fact that the attacks mainly affect females in their active reproductive phase emphasizes the need for mitigating measures. Information campaigns on the consequences of abandoning domestic animals and their presence on beaches, in addition to an active inspection to check and remove abandoned animals on beaches is required. Coordination and transportation are also needed for environmental agencies to capture and send these injured sea turtles to rescue institutions. The uncontrolled presence of domestic animals on the beach is not permitted in most municipalities. When owners are identified violating these ordinances, the proper law enforcement agencies should be notified to take disciplinary action.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (João Carlos Gomes Borges), upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of the Fundação Mamíferos Aquáticos, Projeto Tamar and Petrobras. SubRegional Program for Stranding and Abnormal Activity Monitoring is conducted by Petrobras, as a mitigating measure of the Federal Environmental Licensing conducted by the Brazilian Environmental Agency IBAMA. The authors are grateful to the Graduate Program in Ecology and Environmental Monitoring, Federal University of Paraíba, and the Study and Research Group for the Conservation of Aquatic Organisms of the Pio X University. The Projeto Viva o Peixe-Boi-Marinho of the Aquatic Mammal Foundation, sponsored by Petrobras through the Petrobras Socioenvironmental Program.

Authors’ contributions

Isadora C. Almeida, Rafaelle M. N. Messenger, Fabiola F. A. Gomes, Daniel A. S. Assis contributed to the conception of the idea, analysis of results, and manuscript preparation; Fabiola F. A. Gomes, Davi E. R. Sousa, Rodolfo F. Alves, Isis C. Almeida, Jociery E. V. Parente contributed to the data collection and preparation of figures; João C. G. Borges contributed to the conception of the idea, analysis of results, performed the revision, and supervision.

Competing interest

None.