Introduction

How do actors undertake institutional design in complex systems? Scholars recognize that many international regimes are becoming increasingly complex.Footnote 1 Yet relatively little is known about how actors design or redesign institutions amid this complexity. As participant-observers in the UN negotiations on investment treaty reform, we have watched state officials and other participants grapple with this question for several years. How should we conceptualize these actors who seek to redesign while keenly aware that they are operating within a complex and dynamic system? What principles seem to guide their design approach?

The investment treaty system is increasingly understood as a complex adaptive system or regime complex.Footnote 2 Joost Pauwelyn harnessed insights from complexity science to explain how the investment treaty system gradually evolved from a series of small, historically contingent, and at times accidental steps, and now operates as a largely decentralized system that nonetheless gives rise to emergent patterns on issues like repeat appointments and quasi-precedents.Footnote 3 Others have argued that complexity theory can afford insight into other areas of international law, including trade and environmental law.Footnote 4 Although complexity theory remains on the margins of international law and international relations,Footnote 5 there is a growing trend toward analyzing international regimes as complex adaptive systems.Footnote 6

But where do designers fit within this turn to complexity theory? In short, they typically do not. Complex systems research represents an attempt to understand patterns that emerge in decentralized systems despite the lack of an “omniscient designer.”Footnote 7 Complicated machines are designed; complex ecologies evolve. In Pauwelyn's words, the investment treaty system “was not rationally designed or entered into at one given point in time” and “cannot be explained by a singular motive, agent or plan . . . . There is no single creator, plan or deliberate design.” Rather, many elements came together to “organically produce” the investment treaty system—a combination of contingency, path dependency, and competition among actors that continues to drive its operation and development today.Footnote 8

Yet what happens when a group of designers comes together in a conscious attempt to manage the evolution of a complex adaptive system? That is what we see at the negotiations of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) where states and other actors have been meeting since 2017 to consider whether and how to reform investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).Footnote 9

The UNCITRAL reform process was initially supported by the European Union with the aim of creating a multilateral investment court to replace ISDS.Footnote 10 It soon became clear, however, that no single reform would win out because, while many states agreed ISDS needed to be reformed, they disagreed on how. Some states wanted to pursue reforms to improve ISDS, others sought to replace ISDS with an international court, or some proposed paradigm-shifting reforms to replace investment treaties and international investor-state claims altogether, while others supported a combination of these reform approaches.Footnote 11

The UNCITRAL process has been controversial. On one side, some prominent arbitrators have criticized the process as misguided and going too far.Footnote 12 They view ISDS as a good system that has been unfairly maligned and they warn that the alternatives are deeply problematic for the rule of law and development. On the other, numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and academics have objected that the process lacks ambition and does not go far enough.Footnote 13 By limiting the mandate largely to procedural issues, they say, the process has missed the opportunity to deal with more problematic substantive issues.

In 2021, UNCITRAL approved a work plan to move forward on ISDS reform by pursuing a range of procedural and structural reform options, leaving most substantive issues off the agenda for now but with the possibility of future inclusion.Footnote 14 The work plan proceeds on the assumption that these reforms will be brought together in a multilateral instrument that gives states the choice of which reforms to accept and with respect to which treaties.Footnote 15 This approach is modeled on recent multilateral conventions in tax (the “Multilateral Instrument”) and transparency in arbitration (the “Mauritius Convention”).Footnote 16

How did we get here? Why did the Working Group opt by consensus to move forward with a flexible, adaptable, and evolutionary approach to reform? Having followed this process from the beginning, we have observed that, in addition to the divided views detailed above, the UNCITRAL participants understand the current ISDS system to be complex yet are seeking to design and redesign amid that complexity.Footnote 17 They see themselves as conscious designers but recognize that they cannot completely control the system in which they are intervening or fully predict the consequences of their interventions.

To help explain and theorize what we have observed, we conceptualize these UNCITRAL participants as complex designers and formulate a series of emergent design principles that seem to guide their approach in the reform negotiations.

In formulating these concepts, we employ an abductive sensemaking method that braids together insights from participant-observation at UNCITRAL with complexity theory. We do not argue that negotiators at UNCITRAL will or should adopt these emergent design principles in the final version of the reforms; the aim of this Article is neither predictive nor normative. Instead, we crystallize the underlying logic that we see at work in the UNCITRAL process so far, drawing on complexity theory to yield new frameworks for illuminating what we observe.Footnote 18

In Part I, we outline our methods and position our contribution in the literature. In Part II, we introduce complexity theory and address concerns about applying it to institutions populated by sophisticated, strategic actors. We then turn to the UNCITRAL context and explain how participants at UNCITRAL approach the investment treaty system as a complex adaptive system. They see a system made up of many actors (states, investors, international organizations, law firms, NGOs) and structures (treaties, institutions, awards) that reflect diverse views and interact in myriad ways, often with unpredictable outcomes.Footnote 19

In Part III, we focus on the agency of these actors, conceptualizing participants at UNCITRAL as complex designers—actors who seek to design and redesign institutions within complex adaptive systems. The complex designers we see at UNCITRAL face unpredictability and ongoing change, but still aspire to design or redesign institutions that will deliver on their substantive goals over time. In our observation, they function like landscape architects who focus on both episodic design and adaptive management. Like architects, they attempt to design structures that respond to but also shape the users who will inhabit them. Like gardeners, they consider the environment in deciding what to seed and when, being mindful of the need to tend to their plants and calibrate their caregiving in light of changing conditions.

In Part IV, we develop a series of emergent design principles that we discern underlying the approach of negotiators at UNCITRAL, which we see as key to the evolutionary and experimental approach to reform that they have adopted. We highlight three principles in particular: flexible structures, balanced content, and adaptive management processes.Footnote 20

We argue that there is a coherence and logic underlying the negotiators’ approach and explain how their approach aligns with normative recommendations made by applied complexity theorists. While we do not argue for or against any reform or reform package under discussion, we see value in evolutionary, experimental approaches and in emergent designs generally in turbulent fields characterized by diverse preferences.

In the conclusion, we consider the wider applicability of complex designers and emergent design. Examples from climate change and trade suggest the potential for these concepts to serve as a framework for understanding institutional design in complexity more generally. In a dynamic era marked by unpredictability, division, and complex transnational challenges, we believe these concepts may prove to be increasingly relevant in global governance.

I. Context and Methods

A. Participant Observation and Abductive Sensemaking Methods

Our approach builds on the research of Susan Block-Lieb and Terence Halliday, who studied UNCITRAL as “participant-observer insiders” and used their close observations to produce general theoretical insights about international organizations as lawmakers.Footnote 21 We have been participant-observers in UNCITRAL Working Group III throughout its work on ISDS reform, from 2017 to the present. We attend as academic observers and do not formally advise any government or actor.Footnote 22 Like other scholars who have drawn on close observation for theory building, we aim at conveying how actors perceive their world and act within it by generating new framings.Footnote 23

We sit in the negotiating room throughout the formal deliberations, listening and taking notes. We also have audio recordings of each negotiating session. We collect the formal and informal documents that are made available during the negotiating sessions, including lists of participants, informal summaries, and promotional materials. During the breaks, and in informal settings, we converse with a wide range of negotiators and other actors in the room, including representatives of civil society, international organizations, and private-sector groups. We have supplemented these informal interactions with formal interviews throughout the proceedings, though all material from unofficial discussions is unattributed given the ongoing nature of the process.

These modes of information gathering and exchange fall within the broad tradition of ethnographic methods, which are characterized by sustained observation of a particular site with access to, and repeated interactions with, key actors. Researchers embed themselves in actors’ worlds to understand and conceptualize these worlds. The analytical insights emerge from a process that begins with “an open-minded immersion into the field.”Footnote 24 This process involves establishing rapport with actors and developing empathetic understandings of these actors and how they see the world. In our context, this approach meant prioritizing listening and building trust with participants, so that we could hear how they perceive the negotiations and related concerns, such as their constraints, mandates, audiences, aims, and strategies.

Through repeated interactions over four years, our understanding of these participants and how they approach the negotiations deepened. Our process was abductive and iterative: listening to how participants, particularly negotiators, describe the system and their strategies came first; then comparing this description with existing conceptualizations; then building different conceptualizations when needed; then asking negotiators how particular conceptualizations fit with their understandings; and finally refining our conceptualizations.Footnote 25 This iterative approach to theory building is neither inductive nor deductive, but is consistent with the process of sensemaking in complex fields, which involves a two-way process of fitting data into frames and fitting frames around the data.Footnote 26 This approach also recognizes the researcher as a participant operating inside an open system rather than as an observer sitting outside a closed system looking in.

We employ this abductive method during the negotiations by writing near-contemporaneous blogs about the process. After observing the negotiations and talking to various actors about what has occurred, we draft blogs that explain what we are observing. We often frame these observations within a broader context of either the process or different theoretical literatures. After a week of negotiations is completed, but before publishing these blogs, we share them for comment with a diverse group of participants to gain different perspectives on what happened during the week. We recognize that this dialogue is shaped by how actors perceive us and we update our framings in light of the diverse feedback we receive. The publication of these blogs during the ongoing UNCITRAL process means that they have become part of the group's sensemaking process, which makes us participant-observers, not just observers.

Although our conceptualizations and analyses are our own, in important ways they are also cogenerated. We put forward the ideas in scholarly form, but they emerge from a dialogue with participants in the process—a process sometimes described as “para-ethnography.”Footnote 27 Adopting a similar approach in the trade field, Gregory Shaffer describes it as “the study of social processes through interviewing, and even working with, practitioners ‘who are themselves engaged in quasi-social scientific ‘studies’ of the same processes’ in an effort to understand and respond to them. In this way, the interviews, in part, can be viewed as ‘collaborations’ in the sense of forays into ‘making sense’ of developments.”Footnote 28

We often draw on theories from outside the room to help explain or contextualize a particular dynamic we observe inside the room.Footnote 29 In doing so, we communicate dynamics inside the room to an outside audience and also provide new frames through which participants in the room can reflect on the process. Participants in the room sometimes adopt our framings and language in the negotiations and sometimes reject them, including for strategic reasons. We respond by updating our conceptualizations and terminology in light of developments, as this is an iterative sensemaking process.Footnote 30

We used this abductive mode to develop the ideas in this Article about complex designers and emergent design principles. The advantages of this method stem from proximity: close observation leads to better conceptualizations of how actors see themselves and the reform process, as well as to insights that would be impossible to gain through other means. The downsides of this method, however, also stem from proximity: close and empathetic observation means less critical distance from the actors and the process.Footnote 31 Yet this form of knowledge production is recognized as an important and experimental contribution to ethnographic methods that is occurring various domains, including science, law, finance, politics, and architecture, in the early twenty-first century.Footnote 32

B. Investment Law Literature: Cooperation and Continuity

Scholarship on the investment treaty system has burgeoned in recent decades. It has applied increasingly diverse theories and methods and expanded the boundaries of knowledge about the investment treaty system in several directions. One direction has been to examine how officials think about the investment treaty system, including the purposes they ascribe to investment treaties when negotiating them and to what extent the investment treaty system serves those purposes. Scholarship examining the way officials think about the investment treaty system has emphasized two themes: cooperation and continuity. Many scholars elaborate both but place more emphasis on one or the other. Setting out the two themes individually is helpful for situating our contribution.

The first theme foregrounds the role of cooperation in the investment treaty system. That is, it assumes that states and other actors sign investment treaties or delegate dispute resolution because they believe it will help them reach desired aims. These aims vary by actor, over time, and by circumstance, but scholars have identified a few goals as enduring justifications for the investment treaty system. They include protecting and/or promoting foreign investment,Footnote 33 strengthening domestic legal systems,Footnote 34 and depoliticizing disputes by removing them to the legal sphere.Footnote 35 Scholars debate which justifications should underpin the system normatively and the extent that the system delivers on these goals descriptively.Footnote 36

The cooperation theme corresponds broadly with institutionalist theory. Institutionalist arguments vary along a spectrum: one end is marked by explanations with strong assumptions of full rationality and efficient institutional design; these assumptions are then loosened by degrees until reaching the other end of the spectrum, which is characterized by bounded rationality and inefficient designs that often produce unintended consequences.

Many early explanations of the investment treaty system took as their starting point that states are rational actors that can predict the consequences of signing investment treaties and can design them to maximize mutual gain.Footnote 37 With refinements, substantial research along these lines continues.Footnote 38 For instance, Alan Sykes explains:

The economic explanation for IIAs [international investment agreements] begins with the premise that counterparties must expect to be better off with IIAs than without them or they would not agree to them. An economic theory of IIAs thus necessarily entails a search for sources of mutual gain—the “efficiencies” from concluding them.Footnote 39

Although Sykes does not claim that investment treaties promote efficiency flawlessly, he does claim that “properly crafted and interpreted treaty provisions can ameliorate a range of inefficiencies that would arise in their absence, and that central features of existing IIAs have their genesis in this economic logic.”Footnote 40 Research along these lines has encountered serious challenges in light of evidence that investment treaties may not ameliorate the inefficiencies as expected by some scholars, notably that investment flows may not correlate with investment treaties. If there is no additional investment, scholars began to ask, why do states sign these treaties?

Later scholars answer this question by loosening the assumptions that underpin the rational choice explanations. For instance, Lauge Poulsen loosens the assumption of rationality to allow for cognitive biases, arguing that officials often systematically underestimate the costs and overestimate the benefits of signing investment treaties.Footnote 41 Other scholars, including Taylor St John, emphasize the role played by international organizations in framing relevant decisions, and draw attention to processes that unfold over time and shape officials’ decisions regarding the investment treaty system, like path dependence and feedback effects.Footnote 42

When it comes to ISDS reform debates, these approaches focus attention on a particular line of questions: What goals should the investment treaty system serve and to what extent does it serve those goals? If it does not serve those goals, should it be replaced by other institutional arrangements that will? Sergio Puig and Gregory Shaffer's article exemplifies this approach; they first clarify the goals that the investment treaty system is designed to serve before comparing how well several different institutional arrangements serve them.Footnote 43

The second theme stresses the role of power and centers distributive questions about who benefits and who loses from the investment treaty system. An important aspect of this work is describing and denouncing continuities between imperialism and the contemporary investment treaty system. As Olabisi Akinkugbe summarizes it: at the “heart of the critique” is “rejection of the post-colonial continuities of the technologies of governance and the asymmetry that characterizes foreign investor relations in the host states.”Footnote 44

Many scholars have documented continuities between empire and investment treaties and observed an “enduring contest of interests between capital-exporting states and host states, investors, and local communities.”Footnote 45 In this view, current controversies are not new but are manifestations of older struggles and power dynamics that have dominated international investment law since the nineteenth century, if not earlier. Some scholars regard these struggles as characteristic of capitalism; formal imperialism was just one manifestation of capitalism's boundless tendency toward expansion, and patterns of argumentation in international law that justified imperialism persist today.Footnote 46

Approaches that foreground continuity see a clash between powerful actors seeking investment protection and other actors that endures despite changing political arrangements and ideas. After outlining this continuing contest, Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah argues that the investment treaty system's growth in the 1990s was driven by powerful actors’ adoption of neoliberalism, which reflected an ideological preference for liberalization of markets, trade, and investment.Footnote 47 In his telling, powerful states promoted the investment treaty system with the instrumental purpose of building a law that “served the specific purpose of investment protection” and ensured that “the purpose of investment protection could not be diluted by other considerations.”Footnote 48

In this view, the investment treaty system has long been devoted to investment protection while neglecting competing interests such as human rights and protection of the environment or other public interests. One consequence emphasized by scholars is the empowerment of some actors at the expense of others, such as by conferring both rights and remedies on investors but not providing local communities with either one.Footnote 49 Another critique is that investment treaties unduly constrain national regulatory autonomy, for example, through claims or potential claims having a chilling effect on regulatory measures aimed at public health or environmental protection.Footnote 50

In ISDS reform debates, approaches that emphasize continuities with empire often concentrate attention on asymmetries and alternative visions: Does the investment treaty system unduly benefit and empower foreign investors at the expense of other actors? If so, should it be dismantled? And what alternative visions for investment governance might exist? Calls for transformation and a radical rethinking of the international economic order are particularly pronounced from scholars associated with Third World Approaches to International Law; contributions to a recent Afronomics symposium exemplify this perspective applied to ISDS reform debates.Footnote 51 There is not one alternative vision but many visions emerging from the Global South; for instance, Fabio Morosini and Michelle Ratton Sanchez Badin approach the Global South as “a laboratory for alternative economic order” and several scholars highlight recent African innovations.Footnote 52

C. Bridging Academic and Policy Debates

Despite the many insights produced by the cooperation and continuity approaches, in our capacity as observers at UNCITRAL we have not heard what these academic approaches led us to expect. In fact, we have been struck by a wider disconnect between how the scholarly and policymaking communities perceive the events at UNCITRAL.

The cooperation approach led us to expect that negotiators would actively consider the goals of the investment treaty system and make design decisions in light of these goals. Yet the negotiators rarely discuss the purposes of the investment treaty system and many do not appear to believe they have a mandate to question the system's goals. As we have reflected in our blogs:

We are often asked why the Working Group III debate is bounded. Why are the big questions not being asked? Why are the system's foundational premises not being re-examined in the light of new evidence? Being observers in the room leads us to reframe that question: who has a mandate to ask these sorts of big questions? Many delegates, when asked, emphasize that they have a limited mandate and feel they are constrained by various precedents.Footnote 53

The continuity approach led us to expect the negotiating landscape to be permeated by power and enduring asymmetries, and negotiators to be divided between those seeking stronger investment protection and those with other goals. Of course, power does permeate multilateral negotiations and negotiators know the system's asymmetric history. But in our observations, negotiators view inequalities and asymmetries as part of the terrain on which they work, and define their job as finding ways to achieve their objectives despite differences in resources, status, or experience. Nor do states’ histories as capital exporters or importers explain the positions we have seen. There are no coalitions representing the Global North or Global South; instead, we have found a variety of positions among African states, among Latin American states, among North Atlantic states, and among Asian states.

Many in the scholarly community interpret this disconnect as a defect in the UNCITRAL process—a failure to engage with big questions and understand recent scholarship. They recognize that these negotiations represent the first time states have come together multilaterally, in a forum open to all UN member states, to discuss ISDS reform. Yet they view the discussions as starting from a faulty premise since they did not begin from first principles and they are largely limited to procedural issues when, for many academics and representatives of civil society, substantive issues constitute the system's real problems. No matter what the outcome, in this view, the UNCITRAL Working Group has limited imagination and is tinkering at the margins.

Many in the policymaking community interpret this disconnect as a failure of academics to grapple with the constraints of negotiators’ roles and the real-world challenges that beset reform processes at UNCITRAL and elsewhere. In this view, academics are often utopians with limited understanding of how change occurs in practice or the obstacles that negotiators face when pushing for change. Saying in an academic paper that investment treaties should place obligations on investors is one thing; figuring out how to achieve such a goal in practice is another. Actors taking this view acknowledge that discussions at UNCITRAL are held within certain bounds, but some see the process as strengthening actors and processes that may lead to more ambitious outcomes in combination and over time.

We seek to bridge this disconnect by explaining what we perceive about the process from inside the room, from a deliberately empathetic posture, to audiences outside the room. We turn to complexity theory to make sense of our observations as it best captures the logic we see at work in the room. Complexity theory does not replace other approaches; it complements them. Each approach captures something important, being useful for some purposes and not for others.

The complexity approach we outline next is helpful for understanding how actors seek to manage complex systems. In the case of UNCITRAL—and the contemporary investment treaty system more generally—a defining theme is that states are increasingly (re)asserting their role as managers of that system. This movement and its dynamics are relatively well understood on a unilateral and a bilateral basis.Footnote 54 But how can we understand the way states perform this role multilaterally, often in the presence of profound disagreement, and on many issues simultaneously? This is the “how” that complexity theory helps us to see more clearly.

II. Complexity Theory

A growing number of scholars are embracing complexity theory as a new paradigm for understanding and analyzing social systems, including international regimes.Footnote 55 Why? In large part it is because complexity theory provides a different way of seeing, one that brings systems and ongoing change to the fore, leading to new questions and tools for analysis. As complexity economist Brian Arthur observes:

It gives a different view, one where actions and strategies constantly evolve, where time becomes important, where structures constantly form and re-form, where phenomena appear that are not visible to standard equilibrium analysis, and where a meso-layer between the micro and the macro becomes important. This view . . . gives us a world . . . that is organic, evolutionary, and historically-contingent.Footnote 56

What does that mean when applied to the investment treaty system? Using complexity theory as a starting point shifts our focus away from which problems the investment treaty system seeks to address or its power imbalances and distributive consequences. Instead, complexity theory shifts our focus to “how” questions, including how to identify available strategies of change in contexts of disagreement and unpredictability; how to monitor and manage feedback loops and emergent patterns; and how to enable adaptative management over time. It captures the question we see negotiators frequently asking themselves: “How can I intervene in this complex system most effectively?”

A. The Turn to Complexity Theory

Complexity theory involves the interdisciplinary study of systems that are made up of interconnected parts, which can be natural or human-made. Seeing in systems is foundational for complexity theory, which emphasizes the importance of looking at systems holistically to see patterns that emerge from the (sometimes unpredictable) interaction of various elements. Complex adaptive systems are constituted by the interactions of different actors as well as the structures that emerge from and shape those interactions and actors.Footnote 57 Interactions lead to defining traits of complex systems: feedback, emergence, unpredictability, and non-linear change. As actors and structures interact, feedback is generated that encourages actors to continue down some paths and not others, amplifying some actions while dampening others, and sometimes wearing grooves into the system that bring about temporary stability. Interactions and feedback also generate emergence, which means the system as a whole has properties that do not exist if components are analyzed individually. While feedback effects create path dependency and stability, interactions also bring unpredictability. Small actions can have large effects while large actions have small effects (non-linear change), and actions may have unintended consequences.

Complex systems are often described as organic and contrasted with mechanical, complicated systems. A mechanical, engineered product may have many parts, but the parts interact in predictable ways—you can pull a machine apart, put it back together, and expect it to work in the same way. In contrast, a complex system cannot be taken apart and put back together piece-by-piece. Complex systems are more like ecosystems, in that the whole emerges through interactions and those interactions can be unpredictable and affected by contingencies.

This juxtaposition reflects the view that the natural and social sciences work from two base paradigms.Footnote 58 One is based on Newtonian physics and it sees a world defined by stability, equilibriums, rationality, full knowledge and linearity—like a machine. The other is based on biology and it sees systems defined by evolution, perpetual change, and non-linear dynamics—like an ecosystem. In the social sciences, the former approach is exemplified by neoclassical economics and the latter by complexity economics. One starts from an assumption of stability and rationality and then makes exceptions to account for more ambiguous and messy realities. The other starts from an assumption of constant evolution and then looks for emergent patterns of temporary order that arise in the system.

The turn toward complexity theory in the social sciences divides opinion. For some scholars, it represents a paradigm shift with huge potential, while for others it adds little to well-established literatures on institutionalism or incrementalism.Footnote 59 The machine/ecosystem division also attracts criticism. After all, international regimes are neither mechanical like clocks, nor natural like rainforests. Instead, they consist of a “set of diverse actors who dynamically interact with one another awash in a sea of feedbacks.”Footnote 60 We discuss three reasons for skepticism about the applicability of complexity theory to international regimes, before proposing metrics to think about the relative complexity of different regimes.

The first reason for skepticism about complexity theory is confusion about what it includes and excludes, making it seem diffuse and ambiguous. Some theorists quip that part of complexity theory's wide appeal stems from complexity meaning different things to different people.Footnote 61 While we note loose popular usage (for instance, widespread agreement that the U.S. tax system is too complex without reference to measures of tax code complexity), the scholarly literature does not share this indeterminacy; scholars by and large agree on the properties that define complex systems given above.Footnote 62 In the Section below we bring the definition of a complex system to life by showing how participants at UNCITRAL describe the investment treaty system and how their words fit with defining traits of complex systems.

The second reason for skepticism about complexity theory in the social sciences is that it lacks appreciation for the nuances of particular contexts and how institutional or social landscapes are shaped by their histories. Some uses of complexity theory, notably in economics, have downplayed institutional and social context, hewing closely to complexity theory's origins in biological sciences. Downplaying context is not an intrinsic feature of complexity theory, however, and doing so here would be inappropriate for the richly institutionalized setting we observe at UNCITRAL and inconsistent with our para-ethnographic approach. Officials do not start with a blank slate.Footnote 63 Graham Room, a complexity scholar of public policy, elaborates:

No policy is made on a tabula rasa: any policy is an intervention in a tangled web of institutions that have developed incrementally over extended periods of time and that give each policy context its own specificity. This history shapes the constraints and the opportunities within which policy interventions can then unfold. Policy terrains and policy effects are path dependent.Footnote 64

The officials we observe at UNCITRAL are both constrained and enabled by what happened previously. This is what complexity theorists recognize when they observe that actors seeking change must find the “evolutionary potential in the present” rather than taking “an engineered approach rooted in an idealized future that may never come about.”Footnote 65 If actors start from the present, it means they start with all the structures and constraints and nuances that exist from previous interactions. This perspective has much in common with other theories that emphasize history and gradual institutional change.Footnote 66 There are shared intellectual origins and parallel ideas about institutional evolution and strategies that actors use to change institutions over time.Footnote 67

The third reason for skepticism about complexity theory in the social sciences is that it sometimes appears to present a deterministic argument with no scope for agency. As Paul Cairney explains: “If the complex system is predominantly the causal factor then we lose sight of the role that policy makers play; there may be a tendency to treat the system as a rule-bound structure that leaves minimal room for the role of agency.”Footnote 68 Although some applications of complexity theory assume that the vision of agents is limited to their immediate local surroundings, that assumption is not appropriate here.

If our aim is to understand how sophisticated officials interpret, adapt to, and influence their decision-making environment, then more interpretive accounts of complexity theory are needed.Footnote 69 Officials are not merely shuffling along pre-set paths, they are “agile path creators, able to explore distant hills and valleys, rather than moving myopically along merely local contours.”Footnote 70 The agency of sophisticated actors is central to this Article: in Part III, we introduce the concept of complex designers to put a spotlight on these actors and how they seek to achieve their goals when they see themselves operating in a complex system.Footnote 71

The insights that complexity theory can offer become increasingly relevant as systems grow more complex. All international regimes can be seen as complex adaptive systems yet, as Oran Young argues, the need for flexible and adaptable designs grows stronger as the environments in which these designs are expected to work grow more turbulent and unpredictable.Footnote 72 To would-be designers, some complex systems are more stable and simpler to shape than others. It is helpful to think of complex systems as occupying varying places in the middle of a spectrum that runs from predictable and stable systems on one end to unpredictable and chaotic systems on the far end.Footnote 73

What makes an existing system more complex or less complex to would-be designers? There are no standard metrics to measure or compare the complexity of legal or governance systems.Footnote 74 Yet would-be designers seem to operate with a practical sense that some contexts are more complex than others, so what shapes those perceptions? We articulate six characteristics that shape would-be designers’ perceptions of complexity:Footnote 75

1. Number, diversity, and connections of agents. How many agents and how many different types of agents are involved? How connected are they?

2. Number, diversity, and connections of formal structures. How many formal structures are there and how diverse are they? How connected are they?

3. Number, diversity, and connections of informal practices. How many informal practices exist and how variable are they? How connected are they?

4. Degree of dynamism of the issue area. How fast changing is the issue area? How often do new challenges or new information emerge?

5. Degree to which power is distributed. How widely is power distributed among would-be designers; who needs to agree?

6. Degree to which preferences diverge. How different are the visions of would-be designers for the future of this issue area; what do they want?

In general, an existing system feels more complex to would-be designers as each of these characteristics increase. If new information emerges frequently and would-be designers expect fast change, as in climate governance for instance, it increases perceived complexity. If there are many informal practices and they are highly variable in their operation, it increases perceived complexity. The patterns of connection in a governance system also shape perceived complexity; in general global governance is more complex as network structures grow denser, more modular, or more hierarchical.Footnote 76 We return to relative complexity in the conclusion as we assess the extent to which the emergent design approach we see at UNCITRAL is also visible in other contexts.

B. The Investment Treaty System as a Complex Adaptive System

Listening to participants at UNCITRAL, we are struck by how often their language echoes descriptions of complex adaptive systems. To describe the internal logic of how UNCITRAL participants see the investment treaty system, here we detail three ways in which they describe a system that is complex and full of adaptive actors. We observe negotiators treating the investment treaty system as a system (as thousands of treaties, actors, and other components that interconnect). We observe them treating the system as complex (that is, believing the interconnections give rise to unpredictability, feedback loops, and emergent patterns). And we observe them treating the system as adaptive (because actors shape structures to suit their preferences and are also shaped by those structures, resulting in co-evolutionary dynamics).

First, negotiators treat the investment treaty system as a system. The system is made up of thousands of investment agreements with similar, though not always identical, provisions, which are interpreted and applied by hundreds of arbitral tribunals without a formal doctrine of precedent or system of appellate review. It includes multiple international organizations, including UNCITRAL, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which serve the field in distinct yet overlapping ways. Cases are administered by different institutions, including the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) and the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), under various sets of procedural rules. Negotiators believe that interventions in one part of the system may affect other parts.

Negotiators see themselves operating within an existing system and view their interventions as occurring against this background. As one negotiator put it:

We are not starting from zero. There are over 3000 existing international investment agreements. There have been over 1000 ISDS cases. There are a range of well-established existing institutions like ICSID, the PCA, UNCTAD, the OECD, and, of course, UNCITRAL. There is a wealth of existing experience in practice that can be drawn on and harnessed from modern investment treaties. Accordingly . . ., our approach . . . should reflect the fact that we're not painting on a blank canvas, but rather on one that is already full of color.Footnote 77

Although states usually negotiate investment treaties on a bilateral or regional basis, they view UNCITRAL as a forum where they come together multilaterally to consider what systemic problems exist and which systemic responses might be appropriate. UNCITRAL was selected in large part because of its “genuinely multilateral” nature—all member states of the United Nations General Assembly are members of UNCITRAL.Footnote 78 It is the hub for international commercial law reform within the United Nations system, and has long been active in arbitration, promulgating influential arbitration rules and model laws, including most recently, the Mauritius Convention. As a multilateral instrument designed to update numerous existing agreements, this Convention exemplified a systemic approach.

Negotiators at UNCITRAL frequently emphasize the need for systemic and multilateral approaches. According to one: “[I]t [is] important and necessary to adopt a multilateral approach, necessarily a systemic approach. In other words we need to look at these issues not just from a bilateral point of view but also from a multilateral one. This is the reason why we're here.”Footnote 79 According to another: “[I]n order to identify the problems related to ISDS system, a holistic approach should be taken. These problems are systemic in nature. So they should be neither considered in isolation nor solved by minor adjustments to the current system.”Footnote 80

Taking a systemic approach does not mean that all negotiators think that a single, uniform approach will resolve their problems. Instead, different negotiators have sought different “leverage points” in the system where they could intervene in small ways with the aim of achieving larger, systemic effects.Footnote 81 For example, the European Union and its member states view the selection of adjudicators as a key leverage point in changing the system's underlying paradigm. They argue that, by shifting from arbitral appointments by the disputing parties to permanent appointments by the treaty parties, the “paradigm” for understanding appointments would change from a commercial arbitration model to a public international law one.Footnote 82 Other states, academics, and civil society groups at UNCITRAL see reframing the system's underlying object and purpose to align with sustainable development as a high leverage point.Footnote 83 These approaches accord with arguments that the two highest-impact leverage points for intervening in systems are reframing a system's underlying paradigm and rethinking its goals.Footnote 84

Second, negotiators treat the investment treaty system as a complex system. The investment treaty system is complex in a structural sense because it is multi-levelled and polycentric.Footnote 85 But this is not the essence of what makes a system complex within the meaning of complexity theory. The essential feature of a complex system is that it functions like an ecosystem in the sense that its parts are interconnected and interdependent, meaning you cannot understand the whole from examining the parts in isolation. Instead, the way that they interact is essential to understanding the whole and the outcomes of these interactions can be unpredictable. Interactions can give rise to emergent patterns of temporary order, as well as unintended consequences where an intervention aimed at one problem can unintentionally cause another problem. Complex systems emerge and evolve, they do not proceed like clockwork.

Negotiators, like complexity theorists, often focus on interactions. The reform of ISDS is complex because “different concerns are intertwined and are systemic,” notes one submission.Footnote 86 Because reforms are interconnected, another noted, any individual reforms adopted would not be an “isolated outcome” but would serve “a greater purpose,” as “the sum of all of them is, in itself, a holistic reform.”Footnote 87 In addition to systemic effects, negotiators are mindful about unintended consequences. Reform is “complex,” warned another, so “States must be mindful that any new solutions could also bring new problems into the equation.”Footnote 88

Some negotiators at UNCITRAL seek to work with interconnections. For instance, the European Union advocates for an appellate mechanism to reduce incorrectness and inconsistency, and to decrease the cost and duration of proceedings.Footnote 89 A single reform is intended to have multiple effects. Interconnections, however, also give rise to unpredictability and unintended consequences. Negotiators do not know which reforms will be adopted or whether they will have their intended effect; nor can they predict which cases will be brought or how tribunals will interpret treaty provisions. As one negotiator observed, “[T]he people who . . . developed the [investment treaty] system in the 1960s and 1970s would not have been able to foretell the evolution of the system.”Footnote 90 Awareness of the potential for unintended consequences instills a sense of humility and caution in negotiators.

While negotiators cannot fully predict the system's evolution, they are able to discern emergent patterns. For instance, although the investment treaty system is not multilateral, treaty terms adopted by powerful states are more likely to be adopted by others than those formulated by less powerful states.Footnote 91 The system lacks a doctrine of precedent, yet certain awards develop quasi-precedential status.Footnote 92 And in the absence of permanent adjudicators, a small handful of arbitrators receive most of the appointments and have played an outsized role in driving the field's emerging jurisprudence.Footnote 93 These self-organizing patterns emerge through the interaction of the system's constituent components despite the lack of centralized control.Footnote 94 UNCITRAL negotiators debate how to shift some of these emergent patterns, like the unrepresentative nature of arbitral appointments.

Third, negotiators treat the investment treaty system not only as complex, but also as adaptive. Complex systems are adaptive when they include actors that develop preferences in response to structures and incentives created by the system and also shape those structures and incentives in ways that suit their preferences using their skills and knowledge. There is “a recursive loop” in which “aggregate outcomes form from individual behavior, and individual behavior, in turn, responds to these aggregate outcomes.”Footnote 95 This coevolutionary dynamic is particularly important when dealing with human actors in what some scholars call complex adaptive social systems.Footnote 96

UNCITRAL negotiators debate how to change the structures and incentives of the system to shift the identity, interests, and ideas of various actors within the system, including states, private actors like law firms or arbitrators, public actors like secretariats, and civil society groups. This suggests negotiators are conscious of the importance of agency. When investor-state arbitration was first added to investment treaties, no law firms specialized in investment arbitration, but the creation of these treaty rights spurred law firms to specialize and in turn to help reshape the system by bringing cases that extended its application.Footnote 97 The negotiators know that if they change the system's structures, for instance by regulating third party funding, they could affect the identities, ideas, and interests of actors within the system. They also know that sophisticated actors might seek to negate or work around reforms they dislike.

The negotiators are also conscious of the adaptive nature of their own states. Contemporary negotiating positions are often shaped by decisions made in the past, including treaties signed or positions taken in past cases. While past precedents may constrain negotiators, they do not fully determine contemporary positions: there can be scope for new thinking and change even if negotiators need to navigate carefully between various constraints. The negotiators are also conscious of how the ground frequently shifts underneath their feet: they face new cases, new adjudicatory decisions, other treaty negotiations, the rise of new political parties to power, and shifting geopolitical dynamics. They look to each other—on the UNCITRAL floor and in the corridors—to see how others react to proposals, creating networked behavior that can permit changes of view to coalesce quickly or be stalled indefinitely.

III. Complex Designers

To foreground the agency of actors at UNCITRAL who see themselves operating in a complex system yet still seek to design or redesign it, we introduce the concept of complex designers.

Complex designers include representatives of states as well as actors like NGOs seeking reforms to strengthen environmental protection and industry groups working to protect the interests of investors.Footnote 98 Some actors, like states, are both designers and users.Footnote 99 Complex designers at UNCITRAL are many and varied: they have different identities as well as divergent ideas and interests concerning what the system is and should be. Instead of parsing which actors count as designers or considering the goals and strategies of any particular complex designer, this Article adopts a systems-level approach. Whatever their individual objectives and strategies, as a collective the participants at UNCITRAL are operating as complex designers. How should we conceptualize their approach?

To explain the role of complex designers, we pick up on some of the metaphors used by participants at UNCITRAL and characterize the designers as landscape architects. Landscape architects work with the existing land but can also reshape the land and build or demolish structures. They work toward an overall or emerging vision yet know that their vision will take a long time to come to fruition and may need to be altered in response to changing circumstances. Landscape architects design both to withstand and to work with their environment. Even after their design is implemented, they will need to manage and care for their gardens, planting and pruning each year. In this way, landscape architects engage in both initial design and ongoing management.

We use this metaphor to explain the role of complex designers for three reasons. First, metaphors are an effective method for formulating new concepts and explaining them.Footnote 100 No metaphor is perfect and all metaphors provide ways of seeing and not seeing, but they play a meaningful part in cognitive processes by helping us to understand something new through comparisons with something familiar.Footnote 101

Second, metaphors are a key device used by participants in the UNCITRAL process when attempting to introduce new concepts or persuade other participants to adopt particular approaches. Indeed, the frequent and colorful use of metaphors and analogies has been remarked upon by participants.Footnote 102 Whether the process can deal with both structural and non-structural reforms becomes a question of whether participants can “walk and chew gum at the same time.” The two types of reform have been characterized as “multiple lanes” on a “single highway toward reform utopia.”Footnote 103 There are metaphors about chasing rabbits and constructing with building blocks, to name just a few.Footnote 104

Third, although the landscape architect metaphor has not been used on the UNCITRAL floor, we take inspiration from two of its components that have been invoked repeatedly: architecture and gardening. Complex designers are architects in the sense that they seek to design new structures with users in mind and gardeners in the sense that they try to seed and harvest different reform options in light of changing environmental conditions.

To move from the metaphorical to the analytical, we identify specific procedural and substantive lessons that can be derived from each metaphor. Procedurally, architects remind us of the centrality of episodic design and redesign, while substantively they aim at designing structures with adaptive users in mind. Substantively, gardeners focus on the exigency of environmental fit, while procedurally they remind us of the need for continuous calibration through adaptive management. Most complex designers combine elements of both architecture and gardening, but the balance between the two can shift over time or by context.

A. Architects

The notion of architecture is prominent when it comes to envisaging structures for bringing the reforms together and the role of negotiators in designing those structures.

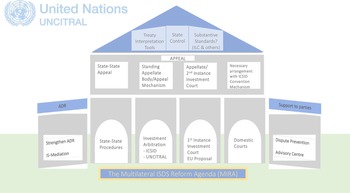

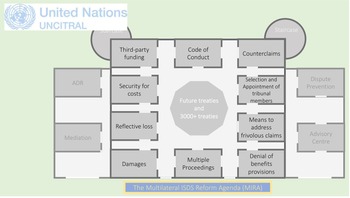

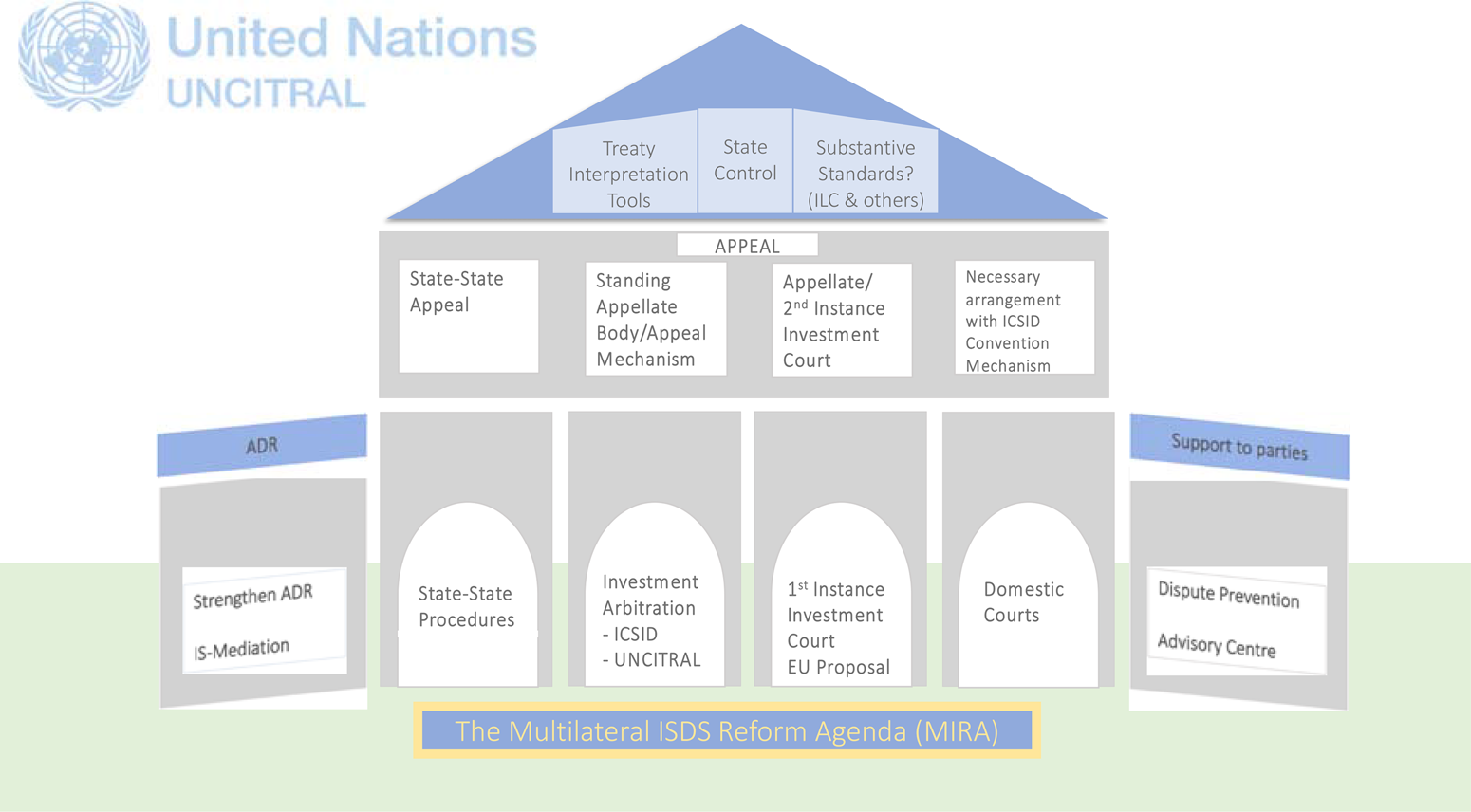

In presentations, the UNCITRAL Secretariat uses architectural images of a house and floor plans to explain how different design options relate to each other (Figures 1 and 2). Different dispute settlement options represent the first and second floors of this house, under a roof of state control. Support for the parties and alternative dispute settlement are indicated by side buildings proximate to the main house but outside it. Different procedural reforms stand for different rooms on a single floor that states can enter or not. The Secretariat outlines “possible architecture” for bringing the reforms together, noting that the “actual architecture” will depend on which reforms are pursued.Footnote 105

Figure 1. Visualization of architectural design on a potential multilateral instrument

Figure 2. Visualization of a floor plan of potential procedural reform options

Other participants employ architectural language to explain the current system's design flaws (e.g., problems arise from its fragmented “architecture”)Footnote 106 and their aspirations for reforms (e.g., “We would like the architecture to be flexible”Footnote 107 and “[O]pen architecture of the standing mechanism could be a way of providing for such flexibility”Footnote 108). In discussing the multilateral instrument, the Chair explains the “need to understand some of the architecture of where we might be headed.”Footnote 109 He has also drawn on architectural metaphors in seeking to move participants to the drawing board:

[W]e heard it expressed that being asked to work on the selection of adjudicators in the context of a standing mechanism was like being asked to dive headfirst into a pool that was not deep enough and where we would hit our head.

As colorful, and as frankly a little bleak as that analogy is, I also think that it is not quite right—because at the stage of the work where we are at, I would suggest the pool has yet to be even designed let alone constructed and filled with water.

Instead, I would suggest that where we are at is that we are standing still on solid ground, hearing about where a pool might go, and what its design might be, but some delegations are already saying that it will be too shallow. And then when the builder and architect suggests otherwise, and offers to draw it out, to design it, and to show the specifications, there seem to be those who are saying we should simply say no, we don't want to see that work, instead we wish to simply continue in our assumption that we were right about the pool's depth without even looking at the plans.Footnote 110

1. Engaging in Episodic Design and Redesign

The idea of architecture serves as a useful way of thinking about the role of complex designers who design and redesign structures and institutions. Negotiators representing states engage in the process of design when they enter into a new treaty or establish a new institution. Likewise, negotiators at UNCITRAL are engaging in a process of redesign by considering how the investment treaty system should be reformed in light of concerns about how it is operating. Such episodic processes of design and redesign tend to be conscious and visible. They involve meetings of states and mandates. Plans are drawn up and institutions are created, modified, and decommissioned.

Architects work intensively during the design phase but are usually not involved once the building is constructed, unless to design extensions or renovations later. Since it is costly and difficult to erect buildings, architects try to anticipate what will be needed in the future, which may signal a flexible layout with rooms that can be used for different purposes or wiring that allows new rooms to be easily added. Similarly, since institutional infrastructure tends to be time-consuming and expensive to set up, and opportunities to redesign it to be rare, complex designers at UNCITRAL aspire to build flexibility and adaptability into their designs. We observe this aim in calls for flexible instruments enabling different parties to accept different obligations, and an adaptable framework that would allow modular additions, like new protocols, to be added in the future.

At UNCITRAL, some negotiators are considering how they could design structures to be put to new purposes over time. For instance, former European Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström observed that any new institution would “need to be flexible in jurisdiction, and able to handle evolution in the content of treaties, for example if countries decide to extend them to cover investor obligations.”Footnote 111 Or if a court of first instance or body of permanent adjudicators is created, some wonder if it could be made available for investor-state and state-state claims and, if so, whether it could include both trade and investment disputes under free trade agreements. Like architects, today's negotiators can design structures that are adaptable and amenable to serving tomorrow's goals, even when they cannot know what those goals will be.

Negotiators are also like architects in that their choices are shaped by the particularities of a given site. As one UNCITRAL participant stated, “[T]opography does dictate what can be done.”Footnote 112 Sometimes architects have to work with existing buildings or intrinsic features such as rocks and gradients. It can take imagination to envisage how unwanted structures or features could be repurposed or remodeled to achieve new ends. So, too, are negotiators often constrained by the structures and features already in place and forced to decide what to keep and what to discard, what to repurpose and what to remodel.

Although architects design for a specific site, the design process often involves creatively recombining features that have been developed and tested elsewhere. Innovation is frequently combinatorial rather than genuinely novel and new institutions often assemble a bricolage of features developed elsewhere.Footnote 113 At UNCITRAL, we find complex designers drawing lessons from their experiences in bilateral and multilateral investment treaty negotiations, as well as from trade law, human rights law, and (to a lesser extent) environmental law. Like architects, one challenge these designers face is to consider new features systemically and in context, since features that work well separately or elsewhere might not work well together or in this context.

2. Designing Structures with Adaptive Users in Mind

Like architects, negotiators at UNCITRAL are tasked with designing structures while keeping adaptive users in mind. When designing buildings, architects must consider the identity, interests, and likely behavior of different users, and design experts often emphasize the importance of taking user-centered approaches.Footnote 114 Like architects, we observe designers at UNCITRAL asking themselves questions such as: Which users and uses do we want to encourage or discourage? What are the interests of different potential users, and how are those users likely to respond to different structures and incentives?

We also observe designers at UNCITRAL asking as a prior set of questions: who should count as a “user” in the investment treaty system? Should cases be brought only by investors or also by states? Should NGOs be permitted to bring cases or participate as non-disputing parties? What about affected communities? Should third-party funders be allowed within the system? Through these sorts of decisions, complex designers craft structures that include or exclude, empower or disempower, different actors.

Various interest groups remind the UNCITRAL designers not to forget users. For instance, a representative of EFILA (European Federation for Investment Law and Arbitration) cautioned that “many architects forget the users” and reminded the system's “architects” that it was “important to keep the users in mind in this whole process.”Footnote 115 To EFILA, investors represent the key users. But to other interest groups, more actors should be recognized as key users, including developing states lacking adequate resources to defend claims or NGOs and community groups desirous of standing to bring and intervene in cases.Footnote 116

The users of the investment treaty system are not limited to disputing parties; they also include adjudicators. Lack of diversity in appointments is a frequent concern raised at UNCITRAL, prompting calls for greater gender and regional balance.Footnote 117 Some actors note the advisability of diversity and inclusivity in general terms;Footnote 118 others point to the role they play in ensuring that decision making draws on the insights of people with varied ideas and lived experiences.Footnote 119 “The decisionmaking process is likely to be perceived as fairer if the decisionmakers are more diverse, thus enhancing the legitimacy of a mechanism,” according to one negotiator, and representation by a range of nationalities increases the likelihood of choosing an adjudicator with some local knowledge.Footnote 120

Designs both shape and are shaped by their users in a coevolutionary manner. As commentators on architecture note, the ability of architects to shape the behaviors of users can be hard to discern (“Good design is obvious. Great design is transparent.”Footnote 121), but there are limits to their power (“People ignore design that ignores people.”Footnote 122). The structures that architects design can influence the identity and behavior of users, but users may also ignore or work around structures they find problematic. “The paradox of impact is that while design shapes the world in profound ways, it is also being shaped by the world,” which means that architects function as “critical mediators,” not complete controllers.Footnote 123

Negotiators at UNCITRAL know they are designing for adaptive actors who navigate structures to pursue their own ideas and interests. If negotiators change the system's structures, they can affect the identities, ideas, and interests of actors within the system. For example, they could require adjudicators to have experience in public international law or international economic law but not international commercial arbitration.Footnote 124 Yet they understand that actors might seek to work around reforms they dislike. For example, interest groups at UNCITRAL suggest investors may bypass ISDS if there is no party appointment, perhaps by signing contracts that permit international commercial arbitration.Footnote 125

Negotiators are keenly aware of the dual role of states as architects and users, and the need to design with users in mind.Footnote 126 These conditions play out in debates over appointments; some actors argue that permitting treaty parties to appoint all the adjudicators would “lead to a mechanism biased in favor of states.”Footnote 127 Others respond that when states appoint permanent adjudicators rather than ad hoc arbitrators, they do so as a treaty party, rather than as a disputing party. As one negotiator put it, in ad hoc appointments, disputing parties typically appoint someone who is likely to “defend their interests,” but “the viewpoint of [states] when making appointments changes radically from ad hoc to permanent system.”Footnote 128

By locating decision-making power in different places (e.g., with the treaty parties instead of the disputing parties) and at different times (e.g., before a case has arisen instead or after one has been filed), UNCITRAL designers may try to influence the identity of appointees and the ideas and incentives that shape the appointments. One submission describes the process as follows:

When appointing adjudicators to the standing mechanism, the contracting parties would be expected to appoint objective adjudicators, rather than ones that are perceived to lean too heavily in favour of investors or states, because they are expected to internalize not only their defensive interests, as potential respondents in investment disputes, but also their offensive interests, i.e. the necessity to ensure an adequate level of protection to their investors. They will therefore take a longer term perspective.Footnote 129

B. Gardeners

Negotiators at UNCITRAL also frequently invoke the imagery of gardening with respect to the process. Negotiators publicly discuss whether they should work on reforms that would permit an “early harvest,” or are ripe for picking; they ask whether the Group should focus on “low hanging fruit” or whether such fruit is already being picked elsewhere.Footnote 130 In private, some characterize planting seeds for reform and cultivating support as engaging in “patient gardening” that leads to feelings of success when some of the “gardening gradually [starts] blooming” or begins “bearing fruit.” They also recognize the need to intervene when the “Garden [has gone] a bit awry.”Footnote 131

1. Designing with Environmental Fit in Mind

For a landscape architect or gardener, understanding the environment is the starting point for design, and working with or against the environment is a continuing process. “Effective gardening requires the right setting: fertile soil, good light, water. It requires a strong view as to what should and should not be grown. . . . It requires a hard-headed willingness to weed what does not belong.”Footnote 132 As one UNCITRAL participant states: “Part of the difference in approaches between structural (architect) and procedural (gardener) reform is that the former seems to want to design to withstand the elements and the landscapers/gardeners are developing with the elements in mind.”Footnote 133

Landscape success is often judged by how well a design suits its wider environment. Gardeners know that different plants are more likely to survive and thrive in different environments. Similarly, different institutions fit different environments.Footnote 134 An institution, like a plant, may grow more durable over time through continued support; for instance, the Group of Seven was created as a temporary experiment but generated unanticipated positive feedback, which led it to endure.Footnote 135 An institution can also generate negative feedback or worsening fit with its wider environment over time, which may engender perceptions of ineffectiveness or illegitimacy.Footnote 136

Perceptions of a legitimacy crisis in ISDS and public discontent clearly motivate the negotiators at UNCITRAL. One asked, “How do we maintain the legitimacy of ISDS?” before answering:

I think perceptions matter and . . . are key to this idea of social license and if I could just briefly quote from a Chief Justice of the English court: “Justice should not only be done but it should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done again.” From Australia's perspective I think it's important that both real and perceived problems should be considered. At the end of the day we are all accountable to the public and we need to counter public perceptions to be relevant.Footnote 137

Perceptions of ISDS within the wider environment matter for those engaging in reforms because they affect the system's legitimacy and functioning.Footnote 138

Even though landscape architects pay close attention to their environment, a wide range of visions is still possible: rigid Versailles-like gardens could be imposed or thoughtful, yet minimal alterations could be made, like Nanzen-in garden in Kyoto. The extent to which designers work with existing materials or transform the landscape is a design choice. Some complex designers at UNCITRAL view architecture as preceding gardening. For instance, one negotiator reasons:

[T]he architect is creating the structures, and must design intelligently, whilst the gardener comes along later (maybe just very slightly later) and has to make sure that the living body which has been created (populated by humans, with all their failings) grows up strong. I've understood for some time that creating the architecture is only the first step, the next step would be getting the people in place who can make sure that there is life in the house, and that is the tending and planting which a gardener would do. You need both, but not at the same time.Footnote 139

Others see a greater commingling of the two functions in the role of the landscaper. As another participant explains, “I wonder if ‘landscaper’ isn't a broader but more accurate [metaphor than] gardener, since there seems to be a suggestion that the gardeners don't have a larger vision, when I think they do.”Footnote 140 The vision for a landscape like Central Park in New York is not implemented once and then left alone, it is created and recreated through many small interventions over time.

Environments can be dynamic, even volatile, and institutions that work well in a stable environment may prove rigid and lacking in resilience in the face of change, such as shifts in the balance of power.Footnote 141 The Appellate Body of the World Trade Organization (WTO) is an example that looms large in the minds of UNCITRAL negotiators. Long considered the “jewel in the crown” of the trading system, the Appellate Body proved vulnerable when the United States refused to appoint new members.Footnote 142 The Appellate Body fit its environment well in the 1990s but proved vulnerable when the political environment changed.

To keep dispute settlement operating, some states at the WTO turned to a little-used option of Article 25 arbitration, invoking and repurposing it as a temporary replacement for appeals.Footnote 143 Vulnerability can accompany some highly centralized designs that have single points of failure or chokepoints, whereas maintaining more diversity and redundancy can help institutions adapt to changing conditions.

2. Engaging in Adaptive Management

Unlike architects, gardeners have not completed their work once an initial design has been implemented. After seeds are planted, gardeners tend their plots, observing young shoots and well-established plants alike and calibrating conditions to ensure that they flourish. The process is more like continuous calibration through adaptive management than episodic design and redesign.

A gardener's interventions are often corrective; observing an increase in rainfall this month, a gardener turns off the irrigation line. Part of the job is to anticipate future scenarios and design accordingly, yet gardeners also know that their work faces threats they cannot predict. They cannot plan everything ahead of time like architects do; gardeners must be flexible and respond to changing conditions as they go.Footnote 144 Thus, despite the UNCITRAL Working Group's agreement on a list of reforms to consider, the chair has emphasized that the schedule “remains open to the identification of new concerns” citing damages as a potential example. “We will always have to remain adaptable and flexible. None of us have a crystal ball.”Footnote 145

When invoking gardening as a metaphor for governing, Eric Liu and Nick Hanauer observe: “Great gardeners would never simply ‘let nature take its course.’ They take responsibility for their gardens.” Gardening presupposes “instability and unpredictability; and thus expects a continuous need for seeding, feeding, and weeding ever-changing systems.” Gardeners know that great gardens are “sustainable only with continuous investment and renewal.” To garden is to “tend.”Footnote 146 Other commentators point out that “the ‘gardening’ skills of senior leadership should be to tend, prune, and harvest ideas.”Footnote 147 For example, the European Union has been seeking to plant the seeds for a new multilateral investment court while also pruning (i.e., terminating) its intra-EU investment treaties.

Complex designers at UNCITRAL recognize the need to seed reforms and then observe them closely, with monitoring processes and tools to intervene if corrective measures are required. Regular meetings of the treaty parties in an interpretive commission serve as one such monitoring mechanism, and interpretive statements are one such tool.Footnote 148 Of course, treaty parties can only intervene or make interpretations if they are able to reach an agreement on how to act in accordance with the requirements of the treaty, which may often prove impossible in practice due to a lack of capacity or differences in interests among the treaty parties. More generally, UNCITRAL has started to function as a common hub where states discuss the system as a whole.Footnote 149

Being in a position to make regular adjustments, whether big or small, is important. Sometimes monitoring may lead to a major redesign, but often it results in tweaks, such as redirecting or expanding a budget or fine-tuning the rules. Dynamic environments require adaptive management and such monitoring and intervention processes are likely to outlive the initial UNCITRAL process. As one negotiator explains of a potential multilateral instrument:

[A]ny such instrument will have to be sufficiently flexible as to be able to build in additional rules that may be necessary in the future. An example of this is the issue of third-party funding. It's an important issue today and has been an important issue over the last few years. But if you looked at the debates around ISDS 10 years ago, or 15 years ago, the question of the party funding was not present. We cannot predict what our successors in 10 or 15 years may view as issues, which may also need to be addressed. So this flexibility for future rules has to be built in.Footnote 150

IV. Emergent Design

Although it is too early to tell which reforms (if any) will ultimately be adopted at UNCITRAL, the approach being taken by the Working Group so far and the key design principles that underlie this approach are already clear. In this Part, we develop three principles we see at UNCITRAL: flexible structures, balanced content, and adaptive management processes. We refer to them as emergent design principles and note that similar notions of emergent design are appearing across a range of areas.Footnote 151 These principles also resemble adaptive management principles and ideas from polycentric, experimentalist, and networked governance—academic literatures that we consider part of the wider turn to complexity theory.Footnote 152

Like many scholars, we turn to complexity theory for analytical reasons, because it is useful for describing and conceptualizing what we observe at UNCITRAL. It helps demonstrate that there is a coherence and logic underlying the negotiators’ approach. We recognize, however, that outlining an approach in detail and connecting theory to practice has normative implications. Making a normative argument is not our main purpose here, and we do not make a normative argument for or against any specific reform to the investment treaty system. But we do see value in emergent design approaches. In that sense we make a broader argument: when negotiators perceive themselves to be acting in a dynamic complex adaptive system, we expect that they will often adopt emergent design approaches, and we believe these approaches may provide effective ways to achieve their aims.

Why are negotiators at UNCITRAL turning to an emergent design approach? It is instructive to return to the six characteristics that shape would-be designers’ perceptions of complexity sketched above, particularly dynamism, power, and preferences. New information about the investment treaty system is emerging ever faster and some negotiators at UNCITRAL feel they may be working just ahead of a new controversial case or large damages award; there is dynamism and a sense of urgency. Power is distributed widely. No actor has the power to insist upon its approach being accepted as the only approach. And state approaches differ sharply. China, the European Union, and the United States all have different visions of the way forward, for example. The preferences of other states, and even their views on the reform mandate being too extensive or not extensive enough, diverge. These characteristics lead negotiators to perceive relatively high levels of complexity in the negotiation.