This article takes a case study and its particular local context to illustrate how aspects of sleeping sickness control measures and tensions within the colonial administration reveal insights into the politics of colonial authority in Tanganyika. Measures to curtail and control human and animal trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness, occupy a primary place in histories of public health, agricultural and economic development, and social interventions in Africa. For colonial states, sleeping sickness represented a ‘threat to the occupation and potential productivity of African land and to the health of people and livestock’ — which meant a fundamental threat to colonial economies.Footnote 1 In the twenty-first century, it is easy to view medical campaigns to eradicate looming epidemics as altruistic and essential services for public health and welfare. However, as Mari Webel has argued, histories of anti-sleeping sickness campaigns in colonial Africa are among the most ‘rigid and draconian manifestations of colonial power’ as expressed by ultimately exploitative and self-serving states, and the long history of sleeping sickness in Africa attests to its sustained centrality as ‘affected African populations have seen successive interventions by different regimes, states, and nongovernmental organizations’.Footnote 2

The historiography of sleeping sickness in East Africa is a developed but ever-broadening field.Footnote 3 The fundamental work is John Ford's 1971 book The Role of Trypanosomiasis in African Ecology, alongside which should be read James Giblin's seminal 1990 article, which reconsidered Ford's work and argued for the importance of further historical research.Footnote 4 Since the early 1970s, when Antony Duggan and Gregory Knight added to Ford's insights, each subsequent decade has brought new and significant contributions.Footnote 5 Maryinez Lyons's pioneering research reconstructed a social history of sleeping sickness control in the Belgian Congo for the years 1900 to 1940 and included detailed analysis of the early colonial utilisation of oppressive isolation camps as a means of controlling infection.Footnote 6 Localised studies offered further insights by narrowing the focus, such as Eileen Fisher's study of sleeping sickness control measures and coercive resettlement programmes on the Ugalla River in Tanzania.Footnote 7 The social constructions and psychological meanings placed on sleeping sickness interventions were imaginatively and evocatively examined in Luise White's work on colonial sleeping sickness control in Northern Rhodesia, which explored the themes of vampire accusations, bloodsucker superstitions, and rumour.Footnote 8 The most comprehensive study remains Kirk Hoppe's Lords of the Fly, which provides a more generalised history of sleeping sickness in the areas around Lake Victoria over the colonial period.Footnote 9 Typical of more recent approaches that have set sleeping sickness within the broader context of colonial and postcolonial development interventions, Julie Weiskopf's social history of resettlement in western Tanzania examines 1930s sleeping sickness control in Buha, Kigoma Region, in tandem with Ujamaa villagization policies of the 1970s.Footnote 10 Beyond East Africa, recent research on the history of sleeping sickness control measures in West Africa and in Portuguese Africa has highlighted the failure of past medical interventions and their profoundly detrimental effects upon populations, greatly diminishing their trust in professional medical interventions of all kinds as well as causing significant side effects and loss of life.Footnote 11 Most recently, Mari Webel expanded ‘our histories of sleeping sickness [1890–1920] by orienting around affected communities and how they responded to and made sense of illness amid colonial control measures’ while considering the fundamental importance of historical local contexts in trajectories of colonial public health. Webel provides ‘productive new insights for an admittedly well-studied phenomenon’ that only highlights how novel case studies, drawing from rich and unexhausted archival material, continue to uncover new findings that reassess and augment the limits of our knowledge.Footnote 12

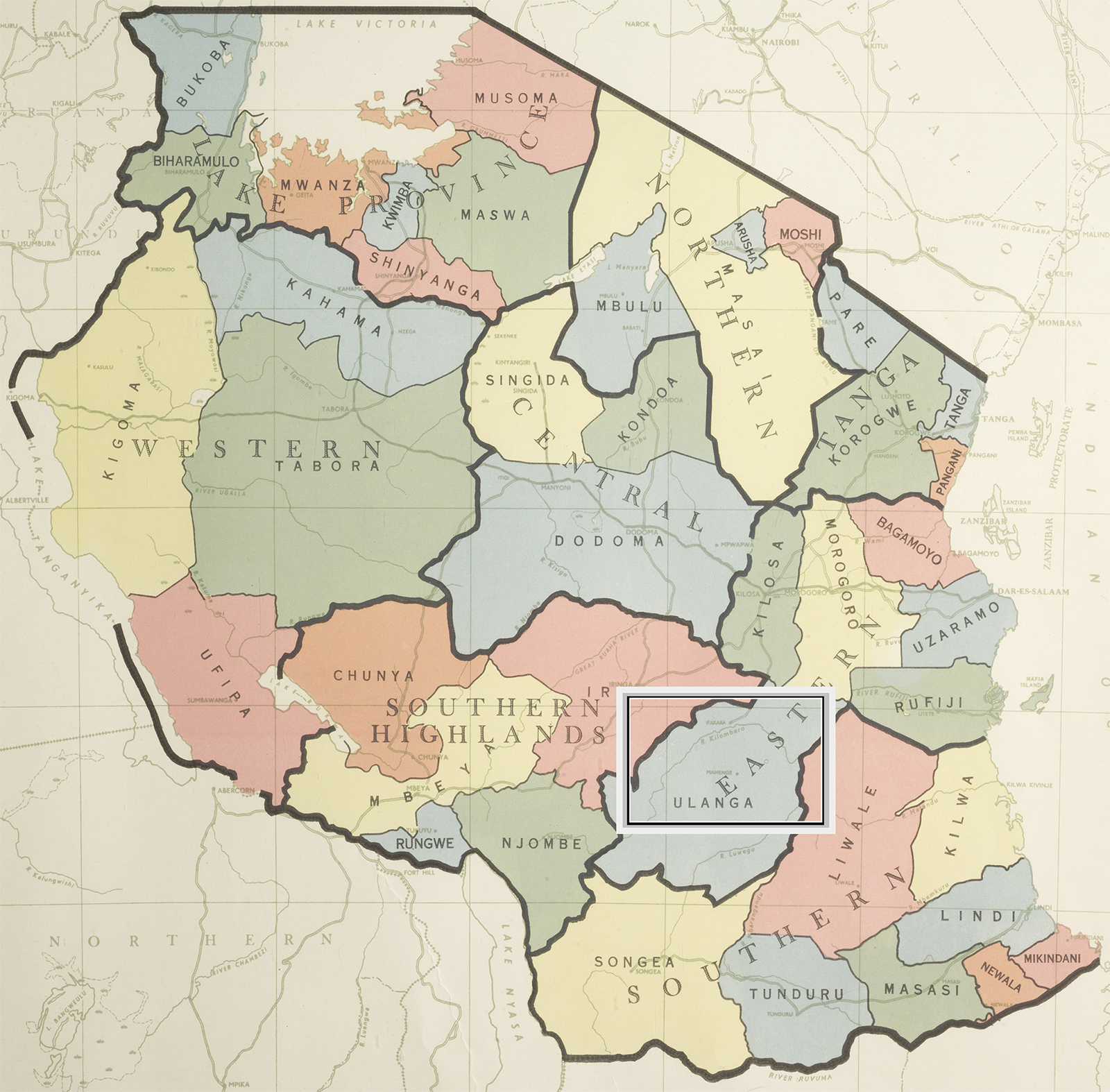

This article follows Webel by linking sleeping sickness control to the politics of colonial development and documents how the threat of widespread epidemic — rather than a response to an outbreak — drove measures that predominantly served as a vehicle to implement colonial visions of a spatial and political reorganisation of rural communities. Colonial approaches evolved, were never uniform, and often heavily ‘depended on the interests and skills of local colonial officials’ and ‘relationships between local people, local elites, and colonial authorities’.Footnote 13 This article takes up this key point to illustrate how sleeping sickness control measures were approached and managed by colonial authorities in the distinct social and political landscape of Ulanga District, a region some 400 kilometres southwest of Dar es Salaam (see Fig. 1, showing the area outlined in Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Tanganyika Government, Atlas of Tanganyika (Dar es Salaam, 1942). Outline showing relative position of area highlighted in Fig. 2.

Source: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Modified with permission.

Fig. 2. Area of Ulanga District showing relevant aspects. Created by author.

The propriety of these measures and the coercive aspects of their implementation are examined alongside an example of local resistance to concentration that exposed tensions and contradictions in the administration's approach to local governance. In Ulanga, the firmest advocate of sleeping sickness measures was A. T. (Arthur Theodore) Culwick, whose role and influence was central. This study presents Culwick as its protagonist and reexamines his character by illuminating certain ideologies that, while not uncommon among colonial officials, strike a discordant note in existing representations and understandings of this individual, highlighting the often-problematic interventions of the self-styled amateur ethnographer in colonial Africa. Culwick subscribed to a paternalistic justification of authoritarian means to achieve progress in his district, resulting in interventions that were far more severe than mere inconveniences for Ulanga's communities. Moreover, this study offers a further example of the colonial tendency to exaggerate crises — in this case, epidemiological crisis — in order to achieve heightened control and pursue additional policy objectives. The Ulanga experience thus has its own distinctive elements that provide insight into the place of concentrated settlement in relation to wider colonial development policies, practices, and principles.Footnote 14

Sleeping sickness and concentration

It is necessary to provide a brief overview of the history of sleeping sickness in East Africa to express how the gravity of the disease in certain places at certain times heightened fears of its spread. This contextualises how the looming shadow of sleeping sickness could then be utilised as justification for colonial campaigns of closer settlement serving ulterior motives.

Colonial concerns about sleeping sickness in East Africa originated in the initial years of the twentieth century. The severity of early experience of the disease, amplified by the initial struggle to understand the epidemiology, set the tone for subsequent engagement.Footnote 15 First identified in Uganda in 1901, by 1905 the epidemic had killed at least 200,000 people in Busoga District alone.Footnote 16 In this period, sleeping sickness was seen in colonial terms as the greatest barrier to Uganda's economic and social development. In 1907, during his tour of East Africa as under-secretary of state for the colonies, Winston Churchill wrote to King Edward VII of the ‘many serious diseases’ in Uganda, of which ‘the worse of all is the sleeping sickness’.Footnote 17 Churchill barely understood the disease, but he grasped the essentials of its potentially devastating impact. ‘It is like an old time wizard's curse’, he told the king:

In order that the spell may work, five separate conditions must all be present: water, trees, bushes, the tsetse fly and one infected person. Remove any one of these and the charm is broken. But let them all be conjoined, and the absolute and certain extermination of every human being within the area is only a question of time.Footnote 18

This thesis of ‘ecological imbalance’ due to ‘quantitative changes in the relationships [between] man, his domestic livestock, and the wild fauna — and the effects of these changes upon . . . the trypanosomes and the tsetse’ was the crucial framework upon which colonial thinking around sleeping sickness and its control developed.Footnote 19 As the tsetse fly is the only identified biological vector of sleeping sickness, its capacity for environmental devastation, specifically with regard to human settlement and husbandry, pivots on an ability to control the fly, the disease, or both.

The first incidence in Tanganyika of a more virulent form of human sleeping sickness (Rhodesian, or Trypanosoma rhodesiense) was identified at Ruvuma River in 1911, followed by an extensive outbreak in Mwanza during 1922.Footnote 20 The response was institutionalised in 1926 by the establishment of a Sleeping Sickness Control division of the Department of Medical Services. In 1930, a research laboratory to investigate trypanosomiasis was established at Tinde, near Shinyanga.Footnote 21 Sleeping sickness research was rooted in the Medical Department, yet its effects were a primary concern for other departments, particularly Agriculture and Game. The stratification of colonial administration was undermined by the tsetse fly as its pervading problems transcended the capacity for interdepartmental cooperation. A Sleeping Sickness Committee was established in 1933 in order to coordinate and manage government response, but this ultimately had limited effect.Footnote 22

Prior to 1923 there had been no practical attempt to target tsetse directly and ‘fight these flies’ in Tanganyika, other than through game extermination.Footnote 23 Previously, wholesale depopulation of tsetse-infested areas was considered a swift but drastic measure to protect populations, and was a first response to curb a rising epidemic and prevent the disease from ‘devastating villages’ and ‘sweeping away entire populations’.Footnote 24 Elsewhere, tsetse presence did not unequivocally signify the existence of sleeping sickness, but this was increasingly assumed. Estimates of the extent of tsetse infestation in the 1920s suggested that two-thirds of Tanganyika's land was under threat.Footnote 25 Land clearances designed to reclaim land from tsetse fly encroachments became a favoured approach to protect populations. These ‘fly barriers’ were maintained by grazing livestock and settlement. Ideas about the ideal settlement density to prevent tsetse encroachment emerged by the 1930s: a population density of between 5 and 25 households to the square mile was deemed dangerous, while a density of 50 to 80 households allowed the maintenance of fly-free land.Footnote 26 Some thought a higher ideal of 100 households to the square mile was required, spurring debates on the risks of soil erosion and diminished agricultural fertility.Footnote 27

By the 1940s, then, colonial thinking in Tanganyika focused on two approaches to sleeping sickness control. The first was to eliminate animal reservoirs of the trypanosomes through the destruction or driving away of all game within the vicinity of settlements. The second required scattered communities living in fly-infested bush to be resettled in large, compact communities, maintained as fly-free areas in a procedure known as concentration. If no suitable area was available, then a resettlement site was created by large-scale bush clearing, relying on the concentrated population to maintain the area fly-free through agriculture and reslashing.Footnote 28 The practice of resettling ‘scattered communities’ into ‘large, compact communities’ had become well established in Tanganyika as the dominant and preferred response to tsetse infestation.

This method of concentration had been evolving since the 1920s.Footnote 29 In 1926, government response to outbreaks already involved ‘the treatment of infected cases and the concentration of the population in fly-free clearings’.Footnote 30 These arrangements resembled the creation of ‘special camps’ to isolate victims, akin to the cordons sanitaires that had been implemented in Belgian Congo.Footnote 31 In 1933 government formalised its own policies with the publication of a sessional paper arguing for ‘the concentration of the people’ wherever possible as the large scale treatment of patients in hospitals was not considered practicable.Footnote 32 The Sleeping Sickness Concentration Committee also highlighted the ‘incidental advantages’ of this process, as perceived by the colonial state, in ‘the creation of economic self-supporting units, the greater practicability of affording medical and educational facilities, and, generally, the increased social amenities and advantages resulting from a denser local population’.Footnote 33 This ‘policy of concentration’ was ideologically extended so that ‘the populations of all sleeping sickness areas should be collected in one great concentration’.Footnote 34 What had begun as ‘wholesale evacuation’ was transformed into ‘beneficial development’ and linked with wide-ranging socioeconomic improvements. Advocates believed that not only would human lives be saved by stemming an epidemic, but that here was a vehicle to drive development and improve livelihoods. It was concluded that ‘by reason of the establishment of these concentrations, the area concerned [Uha, Kigoma Region], which was at the moment particularly backward, would become more highly developed than would have happened under the conditions of the people concerned as they are to-day’.Footnote 35

This policy was considered by many to be aligned with Article 3 of the League of Nations mandate for Tanganyika that legislated Britain's responsibility to ‘promote to the utmost the material and moral well-being and the social progress of its inhabitants’.Footnote 36 Government rationale was such that it was not enough to save peoples’ lives if those people did not then improve their economic standing through greater agricultural productivity, accentuating the impetus to promote a wider development agenda alongside sleeping sickness policies.Footnote 37 By August 1933, the Secretariat resolved to ‘do everything possible to facilitate this execution of this project for concentration’.Footnote 38 For the next decade, the creation of sleeping sickness concentrations effectively became a keystone of British colonial development in Tanganyika.Footnote 39

The Ulanga District

The Ulanga District was topographically and socially diverse, which posed various administrative challenges, and at this time was divided between the highland and valley lowland administrative divisions of Mahenge and Kiberege respectively (see Fig. 2).Footnote 40 Mahenge was situated within a great massif, and Kiberege, to its north, served the Kilombero valley and its extensive floodplain. Mahenge's highland population was less scattered than that of the valley, which was spread more thinly over a vast area consisting of ‘long straggling swampy valleys stretching from the Songea and Njombe borders in the South to the Ruaha River in the North’.Footnote 41 The floodplain of the Kilombero River set the limits to settlement, the alluvial fans around the many tributaries offering rich but vulnerable farmlands. Communications were poor, and fractured further by dramatic seasonal flooding of the river, insubstantial bridges, and limited ferry points. Due to this seasonal flooding, Mahenge was isolated from Kiberege for several months every year. Remote and inaccessible, with a mosaic of niche ecologies, Ulanga was an awkward place to govern effectively.Footnote 42 For Michael Longford, who was district officer (DO) between 1958 and 1960, this was ‘The Back of Beyond’, and he considered the main feature of Mahenge its ‘remoteness and inaccessibility’.Footnote 43 Despite its remoteness, this was a verdant and dynamic region. The valley was a place of extraordinary fertility and abundance, which served its inhabitants well, while its perceived production potential had long piqued European interests. Early German administrators believed the valley could provide rice for the entire colony, and subsequent British visions of grandiose schemes involved railway development and large-scale rice and cotton production.Footnote 44

The social fabric of the valley has been described as comprising ‘groups of people with diverse yet interconnected livelihood systems’.Footnote 45 Commenting on this diversity, Longford wrote that ‘unlike the districts . . . where one important tribe predominated, the African population of Ulanga was made up of seven different tribes’.Footnote 46 This statement does not go far enough to infer the true nature of its complex political landscape. Moreover, the colonial administration had organised Ulanga's population into six Native Authorities, each with their own ‘Tribal Councils’, ‘Chiefs’, and ‘headmen’ or majumbe (sing. jumbe, often pluralised by colonial officials as ‘jumbes’); while settlement patterns, socioecology, and ethnicity varied considerably within each of these units.Footnote 47 This structuring of Native Authorities and their numerous localised subdivisions overlaid strong and distinct cultural identities linked to established regionalisation. The complexity of Ulanga's multiethnic settlement mirrored its ecological variance, the district being made up of a mosaic of ‘distinct cultural entities’.Footnote 48 The 1948 census identified four major groups: Pogoro (48,528), Mbunga (25,087), Bena (23,441), and Ndamba (14,155); and three peripheral groups: Ngindo (including Ndwewe, 6,460), Ngoni (3,583), and Hehe (4,222).Footnote 49 The Mahenge highlands were predominantly home to Pogoro, but also to many Ngindo, Ngoni, and some Ndwewe. Ndamba occupied the middle reaches of the valley, along the levees of the Kilombero and its tributaries. Mbunga maintained a position in the lower valley, centred around Ifakara, the principal town of the valley, while the southwest and upper reaches of the valley were home to Bena. Livelihood and agricultural practices varied greatly between locales. The riverine communities, for example, were adept at canoe transport, fishing, and riparian hunting, while elsewhere there was extensive lowland and upland rice cultivation, hoe cultivation of maize and sorghum, and cotton cultivation. The importance and utilisation of these practices was adapted to the ecological environment and not defined by ethnicity. Pogoro who lived closer to the floodplain, for example, cultivated much more rice than highland Pogoro, who favoured maize cultivation.

An appreciation of the social and physical landscape of Ulanga and its complexities is important, not least as they served as the stimuli for numerous anthropological and ethnographic studies published by A. T. Culwick and his first wife, Geraldine Mary. A 1935 article entitled ‘Culture contact on the fringe of civilisation’ demonstrates a lexicon and attitude typical of 1930s colonial ethnology, but this makes it no less racialised and patronising. The Culwicks cast Ulanga as an area in which it was possible to find ‘a modernized, perhaps detribalized, native society living within a short distance of a community as yet comparatively untouched by the outside world’, but ‘as the area slowly but surely opens its gates to the outside world’ the ‘modern world bursts in upon their primitive seclusion’.Footnote 50

Culwick and concentration

Culwick was stationed in Ulanga for much of the 1930s and early 1940s. His prevailing reputation is that of ‘administrator anthropologist’, and, as described by Peter Pels, he was among the ‘general practitioners’ of colonial rule.Footnote 51 Born in 1905, he read natural sciences at Brasenose, Oxford, and had hoped for a career in scientific research, but later took the Tropical African Services Course required for colonial service.Footnote 52 In 1928 he married Geraldine (née Sheppard), was elected an Ordinary Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute, and arrived in Tanganyika as a cadet. Culwick later returned to Oxford to take its Diploma in Anthropology in 1930–1. Geraldine also took the course but not the examination. The Culwicks were then in Ulanga from 1931, and together they wrote the ethnography for which they are well known — Ubena of the Rivers — as ‘a permanent record of [Bena] tribal history and customs’.Footnote 53 Ubena was viewed as the most progressive area of the district and occupied the paramount position in Culwick's racialised view of the social demography of Ulanga. The following year, aged 31, Culwick was awarded an MBE (Member of the British Empire).Footnote 54 He continued to publish articles on a variety of ethnographic, demographic, nutritional, and scientific topics — many of which were co-authored by Geraldine — and most reported data gathered in Ulanga.Footnote 55 His writings present a strong-willed idealist, ostensibly promoting the social welfare of the Africans in his district, and Culwick was often critical of the shortcomings of government as he perceived them. He was a prominent ‘non-medical academic researcher’ whose voice was influential in shaping certain colonial ideas and policies, particularly around nutrition and demographics.Footnote 56 His pursuit of intellectual and scientific repute drew the ire of fellow officials, and one colleague thought him to be ‘more interested in studying African diet than in handling the mundane tasks of administration’.Footnote 57 He frequently expressed opinions — many of which were published — as to what the job of government was and how that job ought to be done, often to the consternation of his superiors and fellow officers, who did not share his views or zeal. Culwick was once described by one official as possessing ‘wide administrative experience’ — to which another added as marginalia: ‘Although a strong distaste for the ordinary work of an administrative officer’.Footnote 58 Nevertheless, Culwick was Ulanga's ‘man on the spot’ who exercised, in his own words, a ‘system of benign autocracy’ and ‘benevolent authoritarianism’.Footnote 59 These two phrases are as paradoxical as they are delusional. The self-aggrandisement that perfused much of Culwick's colonial writings is echoed later in life by a staunch commitment to segregationist politics, revealing both an enduring inclination towards authoritarianism and an understanding of goodwill that was profoundly hierarchical in nature.

Keenly aware of the activities of Tanganyika's Sleeping Sickness Committee from 1933, and watching the disease penetrate neighbouring districts, Culwick was an enthusiastic supporter of concentrated settlement. Yet despite official policy in Tanganyika allowing for the creation of tsetse barriers and planned resettlement by 1935, before cases of sleeping sickness were confirmed in the district Culwick could only encourage these policies and not compel them. Gentle ‘persuasion’ was applied in the valley, for example by refusing to shoot marauding game where the population was scattered. When sleeping sickness was reported in neighbouring Liwale District in 1936, Culwick hoped to compel closer settlement as a preventative measure, but his superiors did not authorise the concentration of his district. Culwick officially closed the border with Liwale, but could take no further action.Footnote 60 Chief Secretary Phillip Mitchell was among those who worried about the implications of coercion and asked in 1934: ‘Can inducement and persuasion legitimately pass into compulsion in certain circumstances, or can it not?’Footnote 61 This was a controversial and contentious issue and opinion was divided from one provincial commissioner (PC) to the next.Footnote 62 A. E. Kitching was one PC who would not consider closer settlement for any reason during his tenure in order to protect African land rights.Footnote 63 For Culwick, however, it could unquestionably pass. But this was paternalism of the worst and most patronising kind.

Culwick's anthropological research in Ulanga provided data that convinced him of the need to concentrate the district, and especially the Kilombero valley, ‘with its low-lying, disease-ridden valleys’.Footnote 64 By 1939, the Culwicks had published findings that introduced the theory that there was a ‘demographic crisis’ in Ulanga as its population was not managing to reproduce itself.Footnote 65 In 1941 Culwick published ‘A population trend’ in Tanganyika Notes and Records, which reflected on a brief posting to Bukoba in northwest Tanganyika where there were ‘no lack of educational and medical facilities’ and ‘a highly sophisticated people’, in contrast to Ulanga where lived ‘the more primitive inhabitants of the territory, people just beginning to reap the benefits of being drawn into the orbit of world economics’.Footnote 66 Culwick predicted a ‘population landslide’ without intervention.

Attitudes in favour of the urgent need for concentration were shared by others. While Culwick was in Bukoba, Edward Lumley was DO in Ulanga and, on recalling a safari tour of the district in August 1939, wrote that his ‘purpose on this trip was to encourage and if necessary compel people who were living in isolated settlements to concentrate in large villages’.Footnote 67 Lumley observed crop destruction by marauding game and considered resettlement a solution, but remarked that ‘to persuade these people to change the habit of generations and live in organised settlements was never easy. Often compulsion was the only way’.Footnote 68 That only exceptional circumstances could singularly legitimise enforced resettlement frustrated Culwick and those that shared his views, as they presented betterment arguments that were used to justify such dramatic and invasive social reorganisation. The prevalence of game in Ulanga was the easiest argument to make for the need for closer settlement. Marauding hippo, buffalo, elephant, and eland were a constant ‘nuisance to agriculture’, while ‘the only solution seems to be closer settlement’ was a message that colonial officials in Ulanga took ‘every opportunity’ to convey to both local communities and senior government.Footnote 69

In March 1941, in his handing over report after a brief period as DO for Ulanga, John Rooke-Johnston wrote:

I have re-iterated frequently the necessity for concentration. Firstly, as a safeguard against Sleeping Sickness. Secondly, as a means for preventing at least half the crops being taken by marauding game. Thirdly, so that the social services may be developed.Footnote 70

Rooke-Johnston was a colonial official in Buha between 1933 and 1940, during the most extensive sleeping sickness concentration campaign in Tanganyika.Footnote 71 That he advocated for the same in Ulanga, despite the absence of an active epidemic, is not surprising. Rooke-Johnston was a staunch proponent of the strategy's inclusion in general development policy and was prone to histrionics: ‘I re-iterate again, and am firmly convinced that unless the inhabitants of the Ulanga valley are concentrated, they are doomed to extinction’.Footnote 72

From the mid-1930s, Culwick had advocated a scheme to gradually extend the larger settlements of the Kilombero valley — namely Kiberege, Ifakara, and Utengule — and also to gather the entire scattered population living in the bush. He did not receive government support for these plans and, in 1941, retorted: ‘I was informed that no powers of compulsion would be granted to me as His Excellency considered such action would be an unwarranted interference with the liberty of the subject’.Footnote 73 Culwick could only ‘implement the policy . . . so far as certain chiefs and headmen were willing to co-operate’, as he could ‘only stress again the desirability of continuing to concentrate the people of Ulanga in the larger settlements’.Footnote 74

Culwick was impatient, frustrated, and saw his being denied ‘powers of compulsion’ as antithetical to the authoritarianism he felt he exercised, or ought to be able to exercise, in his district. He considered that sensitivities surrounding the mandate were inflated, particularly Article 6, which stated:

In the framing of laws relating to the holding or transfer of land, the Mandatory shall take into consideration native laws and customs, and shall respect the rights and safeguard the interests of the native population.Footnote 75

Colonial interpretations of the mandate were divergent. The implementation of schemes under compulsion were contested. They were either a violation of rights, or a duty to the ‘material and moral well-being and social progress’ of Tanganyikans. District officials such as Culwick saw conservative interpretations of the mandate as an impediment to the means required to meet development ends. He sought to exploit ambiguities, using intellectual clout and rhetoric to make the case, and was fully aware that ‘in spite of the general principles laid down in Article 22 [of the League of Nations Covenant], very divergent policies, particularly in relation to native affairs, [were] possible within the system’.Footnote 76

The first incidence of sleeping sickness in Ulanga, recorded in November 1939, came not from within the district, but as an outbreak on the main labour migration route passing through it. This alarmed the Labour Department, which feared its spread to major employment areas and ultimately as far as sisal estates in Tanga and Handeni. Cases had been identified to the south and east of Mahenge, and measures to control movement through Ulanga, including an abandoned proposal for a quarantine camp, were mooted. For Culwick these confirmed cases in the district were all he needed to begin to resettle its entire population. The process of population concentration in Ulanga was thus catalysed in 1939, by which point a certain colonial approach and paradigm had coalesced. For Culwick, this catalyst was overdue.

The initial centre of the outbreak was at Luhombero, to the southeast of Mahenge. During 1940, a further 76 cases were confirmed, and concentration measures focused on the Luhombero valley.Footnote 77 Elsewhere in Ulanga, Culwick pushed ahead as quickly as permitted. In April 1941, he wrote of the risk to the Kilombero valley from families migrating from Liwale, as conditions in Ulanga were deemed ‘almost ideal for a sleeping sickness epidemic’, and that ‘an outbreak may occur at any time if infected natives from other areas are allowed to enter the “clean” areas’, as had already happened in southern Mahenge.Footnote 78 Many of these families had in fact moved into the adjoining areas of the Eastern Province to avoid the creation of a sleeping sickness concentration in Liwale.Footnote 79

Each proposal for concentration had to be planned in consultation with the relevant government departments, then explained to the local population, and then negotiated through jumbes to seek compliance with the resettlement orders. Compliance was never unanimous. At Mbingu, for example, the population was considered to be ‘very scattered’ and ‘should be collected up at Mbingu itself where there are vast areas of fertile land and plenty of water’.Footnote 80 The resettlement site was originally surveyed in January 1942, but over the next three years it was ‘found impossible to re-settle the area’ because of resistance from the local population.Footnote 81 At this time the Mbingu ‘chiefdom’, under Wakili Rashidi Mpumu, consisted of eight ‘jumbeates’ comprising 466 people.Footnote 82 In the area also resided a Hehe chief — Mzagila Ndapa — under whom were four jumbeates and 406 people.Footnote 83 For Culwick, ‘Ndapa and his Wahehe’ were ‘difficult people’ whom it was advised ‘from the political and administrative point of view’ were ‘best kept together’.Footnote 84 Over half of those to be concentrated at Mbingu were already living in the area around the proposed site nucleus, but they were unwilling to move. Culwick reported that ‘the Native Authorities are in favour of the move, but the populace, who do not appreciate the need for it, naturally wish to remain where they are’.Footnote 85 Culwick was confident of overruling the will of the people, adding there was ‘no great opposition to contend with’.Footnote 86 Processes elsewhere were disrupted and delayed. For Mgeta, he described the process of concentration as a ‘simple concertina’ effect, as he sought to press the population from all sides towards a central point.Footnote 87 Of the 1,375 families bound to occupy the Mgeta settlement, 1,075 were already settled in the Mgeta area; but as at Mbingu, people here were reluctant to comply with government orders to move.

In early 1945, Culwick was determined to push ahead with resettlement at both Mbingu and Mgeta, but soon found himself in bureaucratic crisis. He was informed that, as the selected sites had not been inspected by a member of the Agricultural Department, he could not proceed. This news passed down the hierarchy from the chief secretary to James Cheyne, the provincial commissioner for Eastern Province (PCEP), who wrote in July 1945 regretting ‘that these settlements cannot be made until a survey by an Agricultural Officer has been made’.Footnote 88 Cheyne informed Culwick, acknowledging that ‘cancellation may now cause embarrassment but under [the] circumstances [the] decision must be adhered to’.Footnote 89 Culwick was incensed by this ‘most serious dilemma caused solely by failure [of the] Agricultural Department [to] inspect [the] area’ and felt this would gravely undermine his authority in the district.Footnote 90 ‘And what do I do now?’, he challenged Cheyne. ‘It is all very well for Government — whatever or whoever that may be? — to call a halt but the work has started, and I have thousands of people all ready to move’.Footnote 91 The Director of Medical Services intervened, stressing that Culwick was competent, experienced, and his opinion should be considered reliable. Moreover, those preparing to move had no reserve plantings and crop failure would risk famine. Delay would also defer tax payments. Politically, any deferment of the move was ‘bound to cause discontent’ and ‘foment opposition to the move’.Footnote 92 Culwick was permitted to continue, and the agricultural survey was to be carried out as soon as possible. This example of administrative inconsistency suggests a fundamental fragility to colonial schemes of social reorganisation under sleeping sickness regulations. Implementation attempts by the colonial state were easily undermined by the dysfunction of its own procedures and stymied by local resistance to the flagrant imposition of colonial authority.

This case comes towards the end of a ragged history of concentration in Ulanga that was characterised by the entanglements of administration and a rightful retraction of the ‘willing cooperation’ upon which Culwick relied to ensure successful schemes. These circumstances are best illustrated by the experience of the first attempts to establish concentrations in Ulanga — those imposed at Luhombero — after the initial sleeping sickness cases in 1939 and 1940. Plans to concentrate the population into a settlement at Luhombero involved large numbers of Pogoro and Ngindo, many of whom had previously been living in an area that was evacuated on the enlargement of the Selous Game Reserve in 1940 and who had therefore already been recently displaced.Footnote 93 Ngindo households had been reluctant to move from areas in Liwale and were now repelled by government plans to compel them into condensed settlement. Culwick was aware of this recent history and that Ngindo preferred to live in isolated groups rather than larger settlements. ‘The Ngindo dislike the settled life that agriculture entails’, he wrote in 1938, preferring ‘the lure of wild roaming existence’.Footnote 94 Thirty years later, Ralph Jätzold would reiterate that Ngindo ‘preference for scattered settlements would seem to make them unsuitable to be gathered together in compact villages’.Footnote 95

In October 1941, a ‘considerable number’ of Ngindo under Chief Mponda were reported as having run away from the Luhombero sleeping sickness settlement.Footnote 96 They were pursued by Jumbe Kitolero and one askari, who caught up with them but were fired at with poisoned arrows. The askari fired one rifle shot over their heads and they dispersed. Kitolero then sought help from two local jumbes — Abdulla Mshamu Mbama and Saidi Abdullah — who not only refused their assistance but ‘snatched [the] askari's rifle and threw it against [a] wall’ — splitting its wood — and ‘unsuccessfully attempted [to] beat him up’.Footnote 97 This extraordinary account is a deeply troubling indictment of a colonial regime whose interference with local systems and authority resulted in intercommunity discord and violence.

Culwick considered those who had run away to be ‘deserters’ or ‘fugitives’. Some were said to be hiding in the game reserve, or in open bush in neighbouring Liwale, while others had ‘fled’ to Songea and Tunduru. Culwick's first response was to insist the ‘deserters’ be returned to ‘avoid wholesale desertions and consequent spread [of] sleeping sickness’.Footnote 98 Ngindo dissent had been fuelled by the enforced creation of a settlement that brought Pogoro and Ngindo together. Culwick would argue that the two groups were not mixed, as each community was placed under ‘their own jumbes’, but his distinction mattered little.Footnote 99

Moreover, in the early months of the settlement a spate of witchcraft accusations had been raised, which affected both Ngindo and Pogoro communities.Footnote 100 So intense were feelings that the witchcraft crisis threatened to disintegrate the entire Luhombero settlement, also adversely affecting the nearby Ruaha settlement, formed in 1942. To appease a situation caused by the stresses and social tensions of enforced resettlement, Culwick sent in a witchcraft eradicator in an attempt to ‘cleanse and stabilise’ the settlements.Footnote 101

‘These people do not like being concentrated’, Culwick admitted in his annual report for the year, ‘and we must not blind ourselves to this fact and also the fact they hate Europeans and loathe the Government and desire to be as far away from both as humanly possible’.Footnote 102 Culwick felt that to leave the runaways unpunished would lead to the breakup of the settlements and that ‘government prestige’ would ‘suffer severely’ unless ‘at least the very great majority’ of those who had ‘absconded’ from Luhombero were returned.Footnote 103 He appealed to Liwale for those who had fled there to be returned, but the district commissioner (DC) for Liwale, P. H. Johnston, had a different view. Writing to the provincial commissioner for Southern Province (PCSP) he explained that those who had returned used to live in the Barikiwa, Njenje, and Liwale areas and were attempting to settle in the Njenje, Liwale, and Makata areas in order to avoid concentration in Mahenge. A delegation had appealed for permission to ‘settle again among their own tribesfolk’ and stated that ‘Mwenye Mponda of Mahenge had agreed to their evacuation without consulting them’.Footnote 104 Johnston ‘view[ed] the application of these “runaways” with sympathy’.Footnote 105 Culwick was informed that an individual could only be returned to Mahenge if ‘a Summons is issued against him or a Warrant issued for his arrest’.Footnote 106 This was not an encouragement to do so but a challenge, implying that Culwick could only have his way through litigation. Culwick baulked at this, as he did ‘not wish [the] idea to get round that concentration is a gaol’.Footnote 107 But to all intents and purposes, it was. As Culwick had creatively interpreted the mandate and pushed its limits to create concentrations in Ulanga, so too did he seek to enforce his position by grounding the ‘desertion’ in legislation. Culwick asserted that the ‘deserters’ had acted contrary to Section 8(g) of the Native Authority Ordinance for the ‘Prevention of Spread of Sleeping Sickness’, which applied to the entire district, and decreed that: ‘All natives shall perform any legal work which the Native Authority deems necessary and orders to prevent the spread of sleeping sickness’.Footnote 108 Alongside the mandate, this was also wide open to interpretation.

A political tug-of-war ensued as to whether the runaways could — or should — be compelled to return. The PCEP, E. C. Baker, implored the PCSP to instruct the DC for Liwale ‘that these runaways from Mahenge should not be given a sympathetic welcome’.Footnote 109 What was clear to Culwick was that without cooperation within the administration — by which he meant bending others to his will — imposing this legislation would prove practically impossible.Footnote 110 In terms of numbers, 113 were said to have gone to Songea between late 1941 and early 1943, while 127 were in Liwale. This left 1,710 taxpayers remaining in the settlement, indicating that 14 per cent of the settlers had deserted’.Footnote 111 Culwick criticised colonial officials in Liwale and Songea for affording ‘sanctuary’ for those he held as breaking legal orders and, thereby, ruining ‘discipline . . . and the efficacy of expensive sleeping sickness measurements’.Footnote 112 He felt that continued ‘abscondment’ was ‘encouraged by the failure of the Liwale administration to return a single runaway who has escaped across the border’ and that he ‘cannot stop runaways if it appears . . . that the DC Liwale does not intend to co-operate and his Native Authorities continue to welcome those absconding’.Footnote 113 He feared that unless the deserters were returned to Luhombero, ‘then the whole scheme of concentration in this area [wa]s doomed to failure’.Footnote 114 Liwale's officials were quick to place Culwick ‘under a misapprehension’ that there had been any such failure, but rather Baker had since told Johnston that no one should be returned by force and the so-called runaways could be allowed to stay if all taxes owed to government were paid.Footnote 115 Culwick's arrogance and hubris is exposed as he wrote to the PCEP:

It is not my custom to query my PC's instructions, but I feel bound to point out that important matters of principle have apparently been overlooked, and that serious consequences may follow unless the position is rectified.Footnote 116

Culwick ends his polemic by referencing an ‘enclosed permit from the Native Authority, Songea’ that ‘allows [his] people to break Government's orders’ and ‘will illustrate to what extent discipline and interprovincial cooperation has broken down’.Footnote 117 The permit, dated 10 December 1941 and signed by Nduna Mk. S. [Mkafu Saidi] Palango, lists the names of nine men followed by the statement: ‘Therefore these people are not permitted to be arrested by anyone. They have paid all their tax to me. They are my people’.Footnote 118

It is an irony that when Culwick perceived a threat of migrating families from Liwale to Ulanga, he closed the border, whereas now that people had fled from Ulanga to Liwale (and elsewhere) he insisted they be returned. This was a challenge to his autonomy and a matter more concerned with the politics of colonial authority than the health and welfare of people who ought to be afforded the freedom to manage their own societies. But this was not Culwick's view. His paternalism was a woeful manifestation of that part of Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant which suggested that Tanganyika was ‘inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world’.Footnote 119 Luhombero's deserters offer further examples of considerable dissent against concentration and the coercion required to establish and maintain the settlements. Throughout 1942 and 1943, the situation at Luhombero remained difficult, and Culwick believed that his failure to return the ‘deserters’ to the settlement was the cause of his worsening struggle to foster local support for further resettlement in Ulanga, especially at Mofu, Mbingu, and Mgeta.Footnote 120 During 1942 some voluntarily returned to Luhombero, reportedly because food was ‘plentiful’, and a blind eye was then turned. It was considered that the agricultural success of the settlement might be Culwick's ‘best asset in stopping persons from leaving’ in the future, rather than further acts of coercion.Footnote 121 For Culwick, discipline and authority had been diminished. ‘Government has been weak’, he wrote, and ‘has been successfully defied, has made a laughing-stock of the jumbes, and has failed to keep its promises’.Footnote 122 Despite Culwick's complaints, it is important to note that by 1945, when sleeping sickness resettlement concluded in Ulanga, estimates for the number of those resettled there ranked second highest by district throughout Tanganyika.Footnote 123 Between 1939 and 1945, at least 37,188 people — or 30 per cent of the entire population of Ulanga as recorded in 1948 — were resettled across ten settlements.Footnote 124

Conclusion

The use of coercion to implement sleeping sickness control measures in Tanganyika beyond Ulanga is well-documented and hardly concealed. In a 1949 article for Tanganyika Notes and Records, G. W. Hatchell wrote that ‘it was eventually necessary to employ the more forceful methods of threats of the anger of Government, with consequent punishment, if they refused to move’.Footnote 125 One memorandum detailed how, in enforcing removals, officials ‘may have to “push” the people out and see that the old huts are burned’.Footnote 126 Coercion was thought of positively and even mythologised, while afflicted African populations were patronised. J. P. Moffett saw concentration as a ‘means of salvation’, and wrote that those who had been resettled were ‘now happy and contented’ as if stripped of all agency.Footnote 127 Sleeping sickness was certainly a real problem, tsetse were indeed widespread, and the presence of both in Ulanga was not fabricated. However, the way in which disproportionate threat served as grounds for the wholescale reordering of communities was subterfuge and a gross violation. Writing in 1948, Professor Patrick Buxton, medical entomologist and author of the seminal 1948 text Trypanosomiasis in Eastern Africa, considered that ‘because the Busoga epidemic was such an immense disaster, there is a tendency to exaggerate the importance of human sleeping sickness in Eastern Africa’.Footnote 128 Culwick was among the worst perpetrators of this hyperbole, as evidenced through his tyrannical attempts to effect social engineering disguised as disease control.

This article also speaks to ‘tensions of empire’ as presented by Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler.Footnote 129 It is a contribution to the uncovering of ‘conflicting conceptions of morality and progress, which shaped formal debates as well as subterranean discourses among high and low-level officials’ while illustrating ‘competing agendas for using power, competing strategies for maintaining control, and doubts about the legitimacy of the venture’.Footnote 130 In both cases presented here, Culwick is incandescent at his perception of how interdepartmental and interprovincial cooperation had broken down, providing further evidence of the ‘anxiety of colonizers lest tensions among themselves . . . fracture the façade’.Footnote 131

In 1943, Sleeping Sickness Officer H. Fairbairn proposed that ‘as post-war planning is discussed, it is urged that resettlement of all the people of Tanganyika, who are scattered in tsetse bush, should be adopted as part of the Government's policy’.Footnote 132 Fairbairn considered that grounds for resettlement should be undertaken ‘as part of Government's deliberate policy to improve the social and economic welfare of the people for whom they are responsible’ and noted that resettlement solely as an economic measure remained ‘an interference with the liberty of the subject’.Footnote 133 Fairbairn proposed that the scheme for wholesale resettlement should be separated from the Medical Department and placed under the direction of a specially selected officer. Fairbairn suggested Culwick, outlining that:

The Officer should be selected for his administrative ability and experience, his broad social outlook and scientific approach to social problems, his interest in nutrition and native welfare, his appreciation of the medical, agricultural, veterinary and educational problems with which he will have to deal, and his knowledge of native mentality and his ability to influence it.Footnote 134

This description of the qualities the proposed Officer in Charge of Settlements ought to possess is implicitly Fairbairn's description of Culwick. Moreover, it is not only how Culwick might have once described himself, but remains how Culwick might be broadly understood today. Culwick's published studies and articles are widely cited throughout scholarship, but many inadvertently reproduce his own representations of himself during the colonial era.Footnote 135 Few studies challenge these prevailing representations and approach a holistic analysis. He has therefore largely escaped far-reaching interrogation, critique, or criticism.Footnote 136 Scholarly engagement with Culwick is predominantly bound to the colonial era, and little connection has been made between the apparently genial, liberal, and progressive ‘colonial ethnographer and administrator’ who promoted the paramountcy of African welfare in the 1930s and 1940s, and the later Chairman of the Kenya United Party and supporter of racial segregation under apartheid in South Africa in the 1960s. But is it surprising?

It is clear that Culwick viewed the multiethnic population of Ulanga as a racial hierarchy. He counted Towegale Kiwanga — the mtema (leader) of the Bena — as a ‘close friend’ and his ethnography placed the Bena at the utmost echelon of Ulanga's societies.Footnote 137 Further insights into Culwick's approach to colonial administration are found in his later writings of the 1960s.Footnote 138 He reflected that ‘the prosperity of Towegale's people depended . . . on what some would call his “unwarranted interference with the liberty of the subject”’, recalling the phrase that Culwick and Fairbairn used in relation to the use of coercion in resettlement.Footnote 139 His vision of a benevolent authoritarianism was modelled to some extent on his perception of tribal rule, and he wrote that ‘this tribal African [Kiwanga] realised what Democracy had missed — that 95% of people are only fit to obey orders and lack the mental equipment to form a balanced judgment on any matter other than their own very simple day-to-day affairs’.Footnote 140 While Kiwanga was but one local authority in Ulanga, Culwick considered himself omnipotent. ‘One man, a white man’, he wrote, ‘took the decision and he enforced it. “La loi c'est moi” — dictatorship? Very definitely, but nonetheless valuable for all that’.Footnote 141 This view was certainly not unique to Culwick, but rarely is it so brazenly expressed. His later writings speak directly to his colonial years but reveal a racist and eugenicist mindset that recasts Culwick and implies a distorted disillusionment after empire. In 1968 Culwick condemned the continent: ‘Africa in the raw is returning’, he wrote.Footnote 142

Finally, a concluding note on the colonial legacy of coercive resettlement is particularly important in the Tanzanian context. A conflicting legacy of Julius Nyerere's premiership in postcolonial Tanzania remains the infamous use of compulsion to enforce a state policy of villagisation, largely between 1973 and 1976.Footnote 143 Force followed sufficient resistance or noncompliance to voluntarily participate in Nyerere's vision for the reorganisation of rural Tanzania into Ujamaa villages. I argue that in the first instance, the coercive character of colonial schemes influenced Nyerere's Ujamaa ideals and his emphasis on voluntary rural resettlement. Events such as those which transpired in Ulanga galvanised support for Nyerere and encouraged his ‘hope to revive egalitarianism in Ujamaa’.Footnote 144 However, in the second instance, there developed a ‘creeping breach of Nyerere's own injunction against forcing people [to resettle]’.Footnote 145 The ultimate resort to the use of force and compulsion by the state to achieve its ends reveals how villagisation in Tanzania came to resemble too closely the kind of colonial imposition it had never intended to repeat. As Michael Jennings has noted, ‘Just as the colonial state had responded to resistance to its policies with increasing force, so too the independent state, when faced with similar problems of noncompliance, returned to that default position’.Footnote 146

Despite the crucial distinction of legitimacy between contested colonial authority and a democratically elected government, no state can expect to intervene so dramatically without encountering dissent, and then expect to achieve its ends without coercion.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the Collaborative Research Centre ‘Future Rural Africa’ (CRC-TRR 228/1). I am grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers of The Journal of African History for their comments and suggestions.