“Class- and race-hatred, those poison plants of Europe, have not yet taken root in this country.”

2.1 Introduction

This chapter presents a brief outline of the state of inequality in Brazil and Rio de Janeiro, and with it the conditions that precipitate if not demand hopeful futures, here and now. In The Method of Hope, Reference MiyazakiHirokazu Miyazaki (2004) offered a productive heuristic for approaching hope not merely as a topic of study, but also a method for future-oriented action, while simultaneously cautioning against assumptions around the modularity and generalizability of hope across geopolitical contexts. Yet, given that the ethnographic and analytical cases that inform our inquiry emerge from Brazil, it is necessary to familiarize readers with the histories and current state of affairs with respect to violence and precarity in this context. Most importantly, we also aim to highlight the vibrant political activity and resistance to stigma and criminalization emerging from these present-day communities. As should be evident by now, our focus will be on the faveladas/os of Brazil. Though this is a very specific demographic group that is tasked with navigating a disproportionate amount of violence and precarity, a broader overview of the Brazilian context is productive to understanding how the conditions of favela life came to be in the first place.

2.2 Brazil as Icon of the World’s Future

Brasilien, Ein Land der Zukunft is the title of a book published in 1941 by the Jewish-Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. Released simultaneously in multiple languages, including Portuguese as Brasil, país do futuro and in English as Brazil, Land of the Future, the book is based on trips Zweig made to the country in 1936 and 1940. Reference ZweigZweig (1941) portrayed Brazil for the foreign reader as a “scenically beautiful” tropical country, with “numerous unexplored possibilities” and “destined undoubtedly to play one of the most important parts in the future development of our world” (pp. 1–2). The text was designed to be an indirect critique of Hitler’s hate politics against Jews and other minorities back in Zweig’s European homeland. Influenced by an ideology that we will discuss elsewhere and throughout – the presumed idea that Brazil is a “racial democracy” (Reference AlmeidaAlmeida, 2019) – Reference ZweigZweig (1941) surmised, rather idealistically, that no other country would have better solved the problem of peaceful coexistence among people, “despite all the differences of race, class, color, religion, and creed” (p. 7). In the face of the racist “mania that has brought more disruption and unhappiness into our world [Europe] than any other,” he wondered why Brazil was not “the most strife-torn, most disintegrated country on earth” (p. 7). To his own surprise, Zweig reported witnessing that all races in Brazil,

the Portuguese who conquered and colonized the country; … the native Indian who from immemorial times inhabited the whole region; … the millions of Negroes imported from Africa during the slave days; and the millions of Germans, Italians, and even Japanese who have arrived since as settlers … live in the fullest harmony with one another.

Echoing another contested liberal ideology in Brazil – that of mestiçagem or miscegenation (Munanga, 2004) – Zweig was amazed by what he perceived as “the principle of a free and unsuppressed miscegenation, the complete equalization of black and white, brown and yellow” (p. 8).

Despite the apparent racial harmony and the promise of a congenial future, Zweig’s book and his own relation to Brazil would soon prove to be full of contradictions. In 1941, months after the book’s publication in New York, the author came to Brazil with his wife Lotte Zweig to seek refuge from Nazi persecution. And while Brasilien, Ein Land der Zukunft received support from Getúlio Vargas, the Brazilian president at the time, Vargas was himself a dictator who ideologically sympathized with Nazi Germany, all the while maintaining pragmatic relations with the United States and the United Kingdom (Reference Schwarcz and StarlingSchwarcz & Starling, 2018). Other contradictions would soon emerge, such as Stefan and Lotte Zweig’s suicide a year after the book’s publication – a clear contrast between their idealization of the land of the future and what they narrated to be the “obscurantist forces in the world,” whose defeat they “did not have the patience to wait for” (Reference CarvalhoCarvalho, 2006, p. 31). Zweig had also romanticized a “racial harmony” that in practice did not hold. Brazil was a country that had been founded first on a hierarchy of Europeans and Indigenous people; indeed, since 1500 when they first invaded the land, the Portuguese had violently enslaved or killed various Indigenous peoples. It is estimated that Brazil had been home to about five million inhabitants – a diverse population with sophisticated forms of life, community, and, for some groups, cities, such as the multicentric plaza towns in the Upper Xingu region in the south Amazon (Reference Heckenberger, Russell, Fausto, Toney, Schmidt, Pereira, Franchetto and KuikuroHeckenberger et al., 2008). Before 1500, Indigenous groups spoke between 600 and 1,000 languages (Reference StortoStorto, 2019). Today, this population is approximately 900,000 people and 154 languages (Reference StortoStorto, 2019), numbers that simultaneously signal the deleterious effects of colonization and the survival of Indigenous peoples, whose multinaturalist philosophy – a philosophical system that posits that flora and fauna have the same culture as humans, their difference being that they inhabit different natures (Reference ViveirosViveiros de Castro, 1998) – and conceptions of the earth not as a place to be developed but re-enveloped (i.e., reunified with indigenous ancestral values, see Reference XakriabáXakriabá, 2019) have proven to be fundamental to (global) environmental efforts.

In 1538, the Portuguese were the first to buy and transport slaves to the Americas (Reference GoulartGoulart, 1975; Reference MarquesMarques, 2019). Brazil, thus, is not only the first place that instigated the transatlantic slave trade, but also home to the longest and largest human trafficking operation to the Americas. In addition, it is known for having the largest population of peoples of the African diaspora (Reference Parra, Amado, Lambertucci, Rocha, Antunes and PendaParra et al., 2003), and for its longstanding history of anti-Black violence (Reference AfolabiAfolabi, 2009; Reference TwineTwine, 1997), as will be discussed later. Although slavery was formally abolished in 1888, traces of a society founded on racial hierarchy, inherited privilege, and violence would persist through the Brazil that Zweig encountered in the 1930s to this day. Despite Zweig’s well-intentioned utopian exercise in imagining a tropical future, to some critics the book would become a “piece of propaganda” with wide reach for international and domestic publics alike (Reference CarvalhoCarvalho, 2006). Indeed, “Brasil, país do futuro” is part of a collective Brazilian imagination that endures today, figured in everyday talk and transmuted into several cultural and political artifacts, including lyrics of rock songs widely sung by the youth in the 1990s, soap operas, and films.

In fact, narratives of Brazil as a land of a utopian and harmonious future are older than Zweig’s. Brazilian historian Afonso Arinos de Melo Franco suggested that the very fictional island of Utopia, which Sir Thomas More idealized in the sixteenth century as the place of a perfect society, has a direct connection to Brazil (Reference Melo FrancoMelo Franco, 2000). Elaborating on this link, Reference NagibLucia Nagib (2007) explains that, for Melo Franco, “More’s Utopia is a fictionalized account of the island of Fernando de Noronha,” (p. 8) located in northeastern Brazil. More reportedly learned about Fernando de Noronha from his correspondence with Amerigo Vespucci, the first known European to visit the island. Vespucci described the island as “blessed with abundant fresh water, infinite trees and countless marine as well as terrestrial birds … so gentle that they fear not being held in one’s hands” (as cited in Reference NagibNagib, 2007, p. 8). Nagib commented that More projected this condition of justice and social peace to a territory that is at once perfect and, for that reason, impossible: the island of Utopia, which translates as both “good place” and “no place.” In Reference NagibNagib’s (2007) words:

An essential aspect of Utopia is its impossibility. The word, invented by More, brings together the Greek term topos, or “place,” and the combination of two prefixes, ou, which is negation, and eu, meaning “good quality.” Thus “utopia” signifies both “good place” and “no place,” an ambiguity aimed at camouflaging More’s plans of social change designed for his own country, England. Originally a practical project, Utopia was eventually universalized with the meaning of the impossible dream of an ideal society, whose very perfection makes it unfeasible.

We would venture to say that the ambivalence of a future simultaneously projected as a “good place” and a “no place” – in Zweig and More’s scaling up of the future of Brazil to a larger humanity – indexes the very background that our interlocutors in the field have to deal with on a daily basis. This background has at least two overtones. The first is that Zweig’s idealizations about a racial and natural harmony yielding a potentially perfect society, in fact guide perceptions (in Brazilian middle classes and beyond) about a purported “cordiality” in Brazil (Reference Buarque de Holanda, Green, Langland and SchwarczBuarque de Holanda, 2019). As we discuss below, this cordiality would indicate friendly relations between people across the spectrum of race and class, making Brazil a supposedly “good place” for inter-class and race relations. But this is constantly contradicted by the rates of racial inequality and anti-Black violence, indicating that this “good place” is, in fact, a “no place,” a discourse construction under dispute. Reference Roth-GordonJennifer Roth-Gordon (2017), in her study of race and sociolinguistic relations in a favela and an upper-middle class space in Rio de Janeiro, provides empirical evidence of this ambivalence. She cites, as an example the Brazilianist historian Thomas Skidmore, who summarized the impossibility of Brazilian utopia in the following terms: Brazil’s “ultimate contradiction is between [its] justifiable reputation for personal generosity (‘cordiality’) and the fact of having to live in one of the world’s most unequal societies” (as cited in Reference Roth-GordonRoth-Gordon, 2017, p. 4).

The second overtone is that such aspirations of a supposedly “racially harmonious,” miscegenated, and therefore non-racist country – signaled by Zweig as a model for the future of humanity – in fact legitimize racial domination in (upper) middle-class discourses and other spaces of whiteness in Brazil. Historically, the ideologies of mestiçagem – the construction that people from different colors and social classes would engage in nonviolent relations and form famílias mestiças – and cordial racism – a cultural norm through which “individuals downplay racial differences that might lead to conflict or disagreement, politely ‘tolerating’ blackness but not discussing it directly” (Reference Roth-GordonRoth-Gordon, 2017, pp. 166–167) – have served to maintain a system of inherited hierarchies and privileges that founded Brazil as a nation. Our point here is that the activists we engage in dialogue in the three main collectives in our field – the Instituto Raízes em Movimento, the Instituto Marielle Franco, and the Coletivo Papo Reto – project the time of this utopia (in the sense of “no place”) in a different way. Much of the discursive action of these collectives, including the papo reto activist register discussed in Chapter 4, stands against this idealization of Brazil as supposedly racially harmonious, miscegenated, and where races peacefully coexist. These collectives, particularly the Instituto Marielle Franco and the mourning movement for Marielle, do not focus their action so much on the future (although a notion of an attainable and practical future is obviously part of their agenda), but on the present. Despite her death, by way of their chief motto, “Marielle, presente,” Marielle is narrated metaleptically as presente, as belatedly enacting through them the collective action for social justice that she had envisioned during her lifetime. Favelas are also narrated in these collectives as places of the present; not as imaginary places of a supposedly harmonious future, but as territories where people survive and reinvent life despite the scenario of precariousness that has historically marred Black, indigenous, and poor populations in Brazil. Thus, Brasil, país do futuro, in Zweig terms, would at most be a background against which favela activists as territories of the present rise. As spaces of survival, creativity, and resistance, these territories are rewritten by their residents as “espaços do aqui e agora,” spaces of the here and now.

2.3 Spaces of the Here and Now amid Longstanding Inequities

In this section we outline an overview of the state of inequality in Brazil. Economic inequality, as well as high rates of violence (particularly anti-Black violence, domestic violence against women, and violence against LGBTQ people), are conspicuous features of Brazil. Our objective, of course, is not to provide an exhaustive account of Brazil’s political economy and historical inequalities. Rather, it is to present an outline of data on inequalities that impact life in favelas and that are contextually brought about by favela activists.

Socioeconomic Inequities

Geographically, Brazil is known to be the fifth largest country in the world, with a territory larger than Australia, India, and the continental United States. Its 2022 population of more than 215 million people makes it the seventh most populous country in the world. As noted above, it also has the largest Black population of the African diaspora: in 2019, 56.1% of Brazilians self-declared as Black, 46.7% as White, and 1.1 % as Asian and/or Indigenous (IBGE, 2022). Brazil’s economy is generally among the top ten in the world if measured by gross domestic product,Footnote 1 though it has also been historically one of the most unequal economies (Reference Garmany and PereiraGarmany & Pereira, 2019). The World Inequality Report of 2018, a study led by Thomas Piketty and other economists, pointed out that Brazil at the time was “the democratic country with the highest concentration of income in the top one percent of the pyramid” (Reference Canzian, Mena and AlmeidaCanzian, Mena, & Almeida, 2019, n.p.). The study also highlighted that “Brazil has consistently been ranked among the most unequal countries in the world since data became widely available in the 1980s” (Reference Alvaredo, Chancel, Picketty, Saez and ZucmanAlvaredo et al., 2018, p. 139). In 2015, for instance, “the richest 10% of Brazilian adults – around 14 million people – received half (55%) of all national income … while the bottom half of the population, a group five times larger, earned between four and five time less, at just 12%” (Reference Alvaredo, Chancel, Picketty, Saez and ZucmanAlvaredo et al., 2018, p. 139). In the first quarter of 2021, Brazil reached its highest Gini coefficient of inequality in history: 0.64.Footnote 2 In 2020, amidst the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the poorest sectors of the population saw their income decrease by 33%, while the 10% richest had a decrease of only 3%. Yet in the same year, “The stock market hit record highs, and commodity prices drove up measures of economic growth” (Reference TornaghiTornaghi, 2021, n.p.).

This scenario of economic inequality is hierarchized along the coordinates of race and gender. In a study on the evolution of income metrics vis-à-vis the race of workers between 1986 and 2019, Reference OsorioRafael Osorio (2021) presented some significant data. While there have been changes in people’s racial self-declaration and advances in Black representation in politics and other social sectors – thanks to affirmative action policies in the progressive governments of the Workers’ Party (2003–2016), and especially the activism of the Black movement (Reference GomesGomes, 2017) – “racial income inequality persisted almost untouched in Brazil” (Reference OsorioOsorio, 2021, p. 23) in this period nonetheless. If compared across social classes, the economic disparities between Black and White Brazilians are alarming, as between 1986 and 2019, the average income of the former remained double the average income of the latter. In 2018, only 22% of the richest 10% in Brazil self-identified as Black. Among the poorest 10%, however, Black people constituted almost 80%. Gender also exacerbates the general scenario of inequality we have outlined here. A survey by the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, IBGE) on the role of men and women in the country’s labor force indicated that while 73.7% of men over the age of fifteen held a formal job, only 54.5% of women did (Reference RodriguesRodrigues, 2021). Another index measured by IBGE was the difference in wages between men and women: “In 2019, women received, on average, 77.7% of the amount earned by men. The inequality reaches greater proportions in the functions and positions that ensure the highest earnings. Among directors and managers, women received 61.9% of the income of men. The percentage was also high in the group of science professionals and intellectuals: 63.6%” (n.p.).

Black women occupy the lowest income stratum in Brazil. In 2016, for example, a study by the Centro de Pesquisa em Macroeconomia das Desigualdades (Center for Research on Macroeconomics of Inequalities, MADE) found that “60.5 percent of domestic workers were Black women … and 4.5 percent were Black men, while only 2.5 percent were White or Asian men” (Reference Bottega, Bouza, Cardomingo, Pires and PereiraBottega et al., 2021, p. 3). The MADE researchers compared the demographic makeup of this profession to the profession of film director in the same year. Of the 142 feature films released in Brazil that year, “None of them were directed by a Black woman and only three by Black men” (Reference Bottega, Bouza, Cardomingo, Pires and PereiraBottega et al., 2021, p. 3). According to the MADE economists, in the years 2017 and 2018, although Black women made up the largest demographic segment, they “received only 14.3% of the national income” (p. 2). That amount is less than what was earned by White men in the richest 1% – that is, 0.56% of the country’s total population – who claimed 15.3% of the national income (p. 2). These economic inequalities are aggravated by factors that disproportionately affect Black Brazilians: police violence, less access to employment and policies of income generation, and Brazil’s regressive taxation policy. The MADE researchers point out that “the Brazilian tax system serves as an important instrument for perpetuating Brazilian racism, mainly because it focuses in a relevant way on consumption, proportionally taxing more the poor (mostly Blacks), but also exempting, or taxing in a modest way, an array of incomes and assets belonging to the elite (mostly Whites)” (Reference Bottega, Bouza, Cardomingo, Pires and PereiraBottega et al., 2021, p. 11). The researchers conclude that Brazil needs to “incorporate an anti-racist agenda as a fundamental axis of economic policies” (p. 11), and we would add also as a fundamental axis of public security, in view of the data, history, practices, and policies of (in)securitization that we will present below.

(In)securitization, Policing, and Anti-Black Violence

Researchers in sociolinguistics and security studies have drawn attention to the dynamic correlation between communicative practices and (in)securitization, that is, the “practice of making ‘enemy’ and ‘fear’ the integrative, energetic principle of politics by displacing the democratic principles of freedom and justice” (Reference HuysmansHuysmans, 2014, as cited in Reference Rampton and CharalambousRampton & Charalambous, 2019, p. 79; see also Reference McCluskey and CharalambousMcCluskey & Charalambous, 2021; Reference Rampton, Silva and CharalambousRampton, Silva, & Charalambous, 2022). In this section, we present a general background of urban violence to discuss policies and practices of (in)securitization, such as policing and mass incarceration, that disproportionately affect the lives of Black Brazilians and faveladas/os. The levels of violence in Brazil across time have been appalling. Data from the Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública 2022 indicate that homicides in 2021, while having dropped by 6.5% from the previous year, victimized 47,503 people in Brazil (a rate of 22.3 per 100,000 inhabitants) (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2022, p. 14). This is approximately three times the rate of the United States, another country notorious for its high rate of homicide and gun violence (CDC, 2022). Homicide victims in Brazil are disproportionately Black (77.9%), between 12 and 29 years old (50%), and men (91.3%) (FBSP, 2022, p. 14). Globally, Brazil’s homicide data are also staggering. Brazil has 2.7% of the world’s population but accounts for 20.4% of world homicides. From an economic perspective, data from Brazil’s Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA) and the Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança show that violence costs 6% of Brazil’s annual GDP, equivalent to the country’s investment in public education (IPEA, 2019).

Opinion polls indicate that fear of violence is one of the country’s worst problems (Reference Mesquita NetoMesquita Neto, 2011). Given the rise of authoritarian populisms worldwide (and especially given the rise of Bolsonaro to the presidency in 2018, with an agenda of arming the population and killing “bandidos” or “bandits”) the Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança and the Datafolha Institute have, since 2017, been conducting the “Violência e Democracia” (Violence and Democracy) opinion poll, interviewing 2,100 people so far – a sample of different demographic groups statistically mirroring Brazil’s socioeconomic diversity. The purpose of the survey is to measure (and intersect) the degree of confidence in democracy, adherence to authoritarianism, and fear of violence (in its different manifestations, from urban violence to gender, domestic, and political violence). In the 2022 edition, the poll indicated that the “fear of being murdered has grown considerably from the first survey in 2017: the number went from 74.9% of respondents to 82.5%” (Reference Sodré and LimaSodré & Lima, 2022, p. 62). And although the 2022 survey pointed to Brazilians’ identification with democracy (the propensity to democracy index was 7.25 on a scale of 0 to 10), “The propensity to support authoritarian positions is higher among people who are greatly afraid [of violence] … while among those with less fear such propensity is [lower]” (Reference Sodré and LimaSodré & Lima, 2022, p. 64). Yet, although this poll showed that fear of violence is something that affects different social classes in Brazil, the rates of actual victimization to violence are unequally distributed.

The exceedingly higher figures of violence in areas with higher Black populations point to the increased vulnerability of this demographic group, especially Black men, to violence (Reference AlvesAlves, 2018). Black men are also disproportionately more likely to be victimized by police violence and neoliberal policies of criminalization of poverty, such as mass incarceration (Reference BorgesBorges, 2019; Reference PadovaniPadovani, 2019; Reference Wacquant and LópezWacquant, 2017). Importantly, Brazil has the third largest prison population in the world (Reference BorgesBorges, 2019). The prison population in Brazil grew by 575% between 1990 and 2014, and in that final year 75% of prisoners were young Black men, 67% of them having received basic education (Reference Soares Filho and BuenoSoares Filho & Bueno, 2016). Mass incarceration and policing as social control of poverty thus disproportionately target Black Brazilians. Yet understanding why Black men in Brazil tend to be the preferred target of police violence requires a brief historical contextualization of policing as (in)securitization – in other words, as “a practice not of responding to enemies and fear but of creating them” (Reference HuysmansHuysmans, 2014, p. 3). In 1964, Brazil suffered a coup d’état that established a military dictatorship for twenty-one years. In 1985, a process of redemocratization began, with the declaration of a democratic constitution in 1988, also known as “Constituição Cidadã,” or “Citizen’s Constitution,” replacing the authoritarian constitution promulgated in 1967 by the military. Although Brazil in 1988 “drafted one of the most advanced and sophisticated constitutions in the world … declar[ing] fundamental rights – such as the right to not be subjected to torture, as well as the right of women to be equal to men under the law” (Reference GoldsteinGoldstein, 2013, pp. 55–56), it made very few changes to the role of the armed forces and the police in security. This has to do with the force that the military has exerted in Brazilian politics (Reference LeirnerLeirner, 2020). In the past decades, several attempts to reform the police (including demilitarizing police forces and enhancing the accountability of police agents) were blocked by the lobbying of the armed forces and the military police in the national congress (Reference AmbrosioAmbrosio, 2017; Reference Zaverucha and ZaveruchaZaverucha, 1998). Even though the 1988 constitution eliminated articles related to “national security,” it maintained the status of the armed forces as the main actors in the defense of the State and its institutions, thus keeping the main organ for ostensible policing, the Polícia Militar or military police, under the aegis of military rule.Footnote 3

Instead of military notions of national or internal security, the 1988 legal discourse adopted the concept of “public security,” but did so “in an ambiguous and imprecise way” (Reference Mesquita NetoMesquita Neto, 2011, p. 34). As Mesquita Neto aptly observed, it is not clear in the Citizen’s Constitution whether “public security primarily concerns the protection of the State, the government, or the citizens” (p. 35). Legally and practically, it is as if the democratic transition hadn’t been fully accomplished inasmuch as the textual ambiguity is instantiated in the police’s military approach to citizens. Established in 1970 during the authoritarian regime, the military police are considered an auxiliary force to the army, “and have a very centralized organization, similar to the Army’s organization” (p. 249). The military status of the police reflects authoritarian practices widely held in the army and in Brazilian society. Police officers are trained according to strict military codes of hierarchy and rituals of humiliation, with the intention that their practice aims at internal security. The rationale behind internal security is that “the armed forces and the police are organized to protect the State against political enemies and social movements, and to repress social and political conflicts rather than … maintaining the law and public order or protecting the citizens” (p. 250). In pursuing the authoritarian principles of internal defense and protection of the State, the police have historically “resorted to the use or threat of violence, particularly against underprivileged citizens and groups of Afro-Brazilians or mestizos” (p. 253).

One of the outcomes of the failure to reform the police toward democracy is that Brazil today has one of the most lethal police forces in the world (Reference CaldeiraCaldeira, 2000; Reference Mesquita NetoMesquita Neto, 2011), and police violence disproportionately affects favela residents. This scenario has become worse since the 2018 election of Jair Bolsonaro, a retired army captain who appealed to different groups for his conservative Christian agenda but above all for his law-and-order discourse. Bolsonaro retired from the military at the age of thirty-three because he had conspired to harm the image of then-army minister Leonidas Pires Gonçalves via a bombing (see Reference CarvalhoCarvalho, 2019; Reference Silva, Theodoropoulou and TovarSilva, 2020). After retiring, he became a city councilor (1989), and then a federal deputy (1990–2018) with an almost nonexistent record of legislative bills. Yet he gradually consolidated himself as a cartoonish politician for his racist, homophobic, and misogynist stance, and for his public defense of torture, the military dictatorship’s regime of exception, and the milícias, groups of military officers who compete with the drug trade to control favelas, illegally extorting residents in exchange for “security.” In the executive, Bolsonaro reinforced his discourse of exception against “bandidos” (a category that, for Bolsonaro, included Black people and left-wing sympathizers), issued decrees increasing the population’s gun ownership, and pursued reforming laws to reinforce the violent action of the police. An example of the latter was the PL 882/2019 bill, proposing to extend the “excludente de ilicitude,” or “exemption of illegality,” in the penal code (Reference NorbertoNorberto, 2022). The proposal would allow police officers to bypass punishment if they committed murder “em decorrência de escusável medo, surpresa ou violenta emoção,” or “due to excusable fear, surprise or violent emotion” (as cited in Reference NorbertoNorberto, 2022, n.p.). Interpreted as a broad license to kill, the bill was rejected by the parliament. In the first two years of his administration, however, the number of homicides caused by police reached historical records. In 2019, the police murdered 6,357 people, an increase of 3% compared to 2018 (FBSP, 2019), and in 2020, this number rose again, reaching 6,416 deaths, the highest number since this data was first recorded in 2013 (FBSP, 2020).

The spatiality of violence is all the more crucial as homicide rates may drastically vary depending on where one lived. The State of Rio de Janeiro’s police force is one of the most violent in Brazil. In 2019 and 2020, Rio’s police were responsible for 1,810 and 1,239 killings, respectively. These numbers are excessively high, especially when compared to other countries that are not in a declared civil war. The police in the United States, whose population is twenty times larger than that of Rio de Janeiro, in 2019 and 2020, respectively, killed 999 and 1,020 people (Washington Post, 2020, 2022). In the city of Rio de Janeiro, in 2016, catchment area of the 15th Police District, which covers upper-middle class neighborhoods such as Gávea, Jardim Botânico and Lagoa, recorded four homicides (1.64/100,000 inhabitants); in the 21st Police District, which serves the Complexo da Maré favelas, this figure rose to seventy-six homicides in the same year (27.75/100,000 inhabitants) (Reference GloboO Globo, 2022). Brazil’s Public Security Forum (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública), which systematizes such data, concluded that in Brazil, social rights are “regulated by social markers of difference (race, class, gender, sexuality, age, disability)” (Rede Brasil Atual, 2021, n.p.). The higher impact of urban and police violence on Black Brazilians and residents of favelas indicates that, in practical terms, violence against these minorities is socially legitimate, “As if Black youths and the poor did not have the right to non-discrimination, to life and to physical integrity … While civil, social, and political rights are formally recognized in the letter of the law, there is an immense abyss between legal formality and the effectivity of rights in practice” (Rede Brasil Atual, 2021, n.p.).

Although proposals for more democratic security and policing exist in Brazil – such as the Latin American movements for segurança cidadã (citizen security) that, in resisting dictatorial rule in the 1970s, advanced an understanding of security in democratic rather than authoritarian terms – their effective implementation has encountered difficulties due to the aforementioned power of the military and conservative lobbies.Footnote 4 Further, ethnographies such as Reference CaldeiraCaldeira’s (2000) study of urban violence and segregation in São Paulo have pointed out that part of the difficulties in reforming the police have to do with the support of part of the population, “Who have been passionately opposed … to controlling police abuses … and reform[ing] the justice system” (p. 209). In Rio de Janeiro, the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), a proposal that at first seemed to resemble community policing, initiated in 2008 (Reference MenezesMenezes, 2015; Reference Menezes and CorrêaMenezes & Corrêa, 2018). Before pacificação, or pacification, most favelas did not have permanent policing, and police raids conducted in order to confront the drug trade tended to victimize many people. One of our interlocutors in the field, while critical of the idea of pacifying the territory through policing rather than investment in education, culture, work, and income, told us that “it’s better to have some form of police than the usual violent raids that leave behind a violent trail of dead black men.” When Daniel arrived in Complexo do Alemão to start fieldwork in 2012, the first UPPs were being deployed in the neighborhood. The public aim of pacification was to promote permanent policing in favelas and to remove weapons from the retail drug trade. New police officers were hired, with the alleged expectation that policing would be moved away from authoritarian practices and toward a model of “proximity policing” (Reference Muniz and MelloMuniz & Melo, 2015; Reference Menezes and CorrêaMenezes & Corrêa, 2018; Reference Rodrigues and SiqueiraRodrigues & Siqueira, 2012). Although community policing was at least laterally reflective of the initial design of this experiment, the connections of pacification to real estate, media, military, and government investments prior to the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games (Reference Gaffney, Gruneau and HorneGaffney, 2015; Reference Grassiani and MüllerGrassiani & Muller, 2019; Reference Silva, Facina and LopesSilva, Facina, & Lopes, 2015), in addition to the historical anti-Black police violence that we described above, soon signaled the distance between this policing model and the citizen security that progressives in Latin America aspired for (Reference BatistaBatista, 2011; Reference Facina and PalombiniFacina & Palombini, 2017). In practice, the new police officers worked in the same military institution as the former ones. Further, alongside an often conspicuously aggressive treatment of Black folks and faveladas/os, during pacification the police had to accommodate their relations – which have not only been confrontational, but also featuring “agreements and political exchanges” (Reference Machado da Silva and MenezesMachado da Silva & Menezes, 2019, p. 531; Reference Telles and HirataTelles & Hirata, 2007) – to the retail drug traffic in favelas. The case studies that we will discuss in Chapters 4 and 5 document metadiscourses of favela activists in response to police pacification prior to and during the mega-events in Rio de Janeiro. These metadiscourses, associated with sociolinguistic and digital strategies of denouncing police abuses and human rights violations, point to the potent “counter-securitization” in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas (Reference Fridolfson and ElanderFridolfson & Elander, 2021; Reference Rampton, Silva and CharalambousRampton, Silva, & Charalambous, 2022) – that is, resistance to securitization as the exceptional use of force against an enemy through tactics that may ultimately move security to a more democratic ground.

After the Olympic games and the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, both in 2016, Rio de Janeiro and Brazil experienced a serious political and economic crisis. Since then, police pacification has been underfunded and nearing its end. Alongside Bolsonaro’s election to the federal executive in 2018, Wilson Witzel, a former judge, was voted in as the governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro with a strong agenda of “penal populism” (Reference PrattPratt, 2007). When elected, Witzel notoriously announced that during police raids in favelas, the police would kill anyone carrying a rifle. In his words: “O correto é matar o bandido que está de fuzil. A polícia vai fazer o correto: vai mirar na cabecinha e … fogo! Para não ter erro,” or “The correct thing to do is to kill the criminal who is carrying a rifle. The police will do the right thing: they will aim at the little head and … fire! So there is no chance of error” (as cited in Reference WitzelWitzel, 2018). In his first year in office, Witzel became popular for mediatized performances of penal populism. For example, in May 2019, he was filmed inside a civil police helicopter during an operation, in his words, “para dar fim à bandidagem,” or “to put an end to criminality” (Reference MacielMaciel, 2019, n.p.). From there, police officers fired ten shots at a tent in a peripheral hillside that they imagined harbored drug dealers, but was actually a (luckily empty) pilgrimage stand for evangelicals. After Witzel’s impeachment over corruption charges in 2020, Claudio Castro, his vice president, took over as Rio de Janeiro’s governor and was reelected in 2022 for a four-year tenure. Like Witzel, Castro has reinforced violent police action. In just under a year leading the Rio de Janeiro executive and its police, Castro has been at the forefront of three of the five largest police massacres in Rio de Janeiro’s entire history. In May 2021, the police killed at least twenty-eight people in a raid in the Favela of Jacarezinho. One police officer was killed at the beginning of the raid, which possibly explains the high number of killings by the police, potentially as revenge for the deceased officer (Reference FishmanFishman, 2021). In May 2022 in Complexo da Penha, a favela contiguous to Complexo do Alemão, the police killed twenty-four people in a single operation. Finally, a raid in July 2022 in Complexo do Alemão left seventeen people dead, including one police officer. Ignoring principles of police intelligence (Reference Proença Júnior and MunizProença Júnior & Muniz, 2017), these raids function as a message to (digital) audiences who in Bolsonarismo are constituted as committed to the tropes of penal populism (Reference PrattPratt, 2007) and attacks on an “enemy” (Reference HuysmansHuysmans, 2014) as a means to security.

All in all, this scenario clearly points to a model of necropolitics – “politics as the work of death” (Reference MbembeMbembe, 2003, p. 16) – that informs policing as a central agent of (in)securitization in Brazil. However, our aim here is not to detail this dystopian scenario for its own sake, but fundamentally for its status as a background against which life is taken by activists and residents as “emergência” (emergency and emergence) in favelas. For this reason, it is important to note that this necropolitical model has been resisted by many agents in Brazil, including the collectives we engage with in the following chapters. Yet before we detail their enregistered and digital action, it is important to summarize another normative armed agent that disproportionately impacts life in favelas – “o mundo do crime,” or “the world of crime.”

2.4 “Mundo do Crime”

In 1999, Luiz Antônio Machado da Silva, a leading sociologist from Rio de Janeiro, offered an important interpretative key to the ordering of violence in Brazilian cities. As we have discussed, in the mid-1980s and 1990s, violent crime escalated considerably in Brazilian urban centers, becoming a salient marker in everyday conversation and politics (Reference AdornoAdorno, 2013; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira, 2000; Reference ZaluarZaluar, 2004). Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (1999) opposed an institutionalist interpretation of the rise of violent crime – namely, violent crime as an effect of a not-fully-institutional state, especially with Brazil on a course of redemocratization after the end of the military dictatorship in 1985. This vision, predicated on the idea of a state still undergoing institutional development while facing “technical, legal and financial obstacles affecting police procedures and the administration of justice” (Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva, 1999, p. 115), explained neither the ordered nature of crime – violent crime emerging as “organized” – nor the internal logic of the “mundo do crime” or “world of crime” – the moral and conceptual baseline undergirding dispositions for action in this sphere, something that would not take the logic of the state into consideration. Thus, in his pioneering key, Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (1999) proposed organized crime to be “a social reality with its own logic … which works with a certain independence in relation to other problems and social phenomena” (p. 115), such as the organization of the state itself. An example of this alternative logic was the emergence of the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC; Capital First Command), São Paulo’s major faction. Following abuses such as the massive killing of 111 inmates by the police after a rebellion in the Carandiru House of Detention, nationally known as “Massacre do Carandiru,” prisoners created the PCC to “extinguish the climate of constant war” among the incarcerated and to protect themselves from the “system” (Reference BiondiBiondi, 2016, p. 35). The PCC would soon gather prisoners and criminal agents out on the streets together into a “brotherhood” (Reference FeltranFeltran, 2018), mediating the business of drug trafficking and other illegal activities and establishing its own ethic. Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (1999) suggested that the “world of crime” is “a form of organized social life, that is … a complex of forms of conduct that does not take public order as reference” (p. 121). In its Reference WittgensteinWittgensteinian (1953) sense, a form of life is grounded on ethics and on regulated modes of action. Addressing the urgency to understand this form, Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (1999) posed for social scientists studying violence the challenge of explaining this ethical sphere – that is, “to discover how the agents of violent crime formulate the justifications for their behavior and which cultural meanings they express” (p. 121).

Ever since Machado da Silva proposed the hypothesis that violent crime may coexist with another different normative regime, the state, and may not refer to the modes of conduct of public order, several ethnographies have confirmed his thesis, albeit with modifications. Various empirical works, including Reference BiondiBiondi (2016), Reference FeltranFeltran (2020), Reference Galdeano and SilvaGaldeano (2017), Reference HirataHirata (2018), and Reference MenezesMenezes (2015), have demonstrated that the “world of crime” has become an “instance of authority” (Reference Galdeano and SilvaGaldeano, 2017, p. 58) for peripheral residents, achieving a legitimacy in these territories that coexists, in a tense and conflictive way, with the legitimacy of the state. In São Paulo, for example, the coexistence of and mutual relationship between these normative regimes go beyond the borders of the peripheries, and affect life more broadly. In a text about his fifteen years of ethnographic research in the peripheral district of São Paulo’s Sapopemba, Reference FeltranFeltran (2015) commented that he learned

that we do not have only one justice system, nor only one law operating in São Paulo. That we do not have a democracy, nor a dictatorship, nor do we live in neoliberal totalitarianism, but that we have all of these regimes coexisting, depending on the segment of the population that is observed and the different situations that are presented to them.

Understanding that “crime” and “state” are distinct normative spheres that variably affect the population, Reference FeltranFeltran (2012) explained that in the peripheries of São Paulo, the PCC has implemented its own informal “justice system.” This is a mechanism to regulate and control the illicit markets of drugs, car dismantling, robberies, and the like. In this structure, which also regulates the moral dispositions of its members, homicide is no longer the key to conflict resolution, but rather debates among “brothers” who form the armed collective. Thus, “The boy who previously had to kill a colleague for a R$ 5 (US$ 1) debt in order to be respected among his peers, now cannot kill him anymore: he must turn to the PCC to claim reparation for the damage” (Reference FeltranFeltran, 2012, p. 241). This new ethic of crime interrupted a cycle of revenge that would have spawned other killings – the colleague’s brother could have tried to avenge him, and so on. Reference FeltranFeltran (2012) argued that the reduction in homicide numbers in São Paulo since 2001, boasted by the state government as an achievement of its public security policy, has resulted less from the mass incarceration implemented by the state than from measures and strategies adopted by the PCC. The result of the “crime policy,” Reference FeltranFeltran (2012) argues, was a reduction of 70% of murders in São Paulo between 2001 and 2011.

In the Northeastern state of Ceará, a pacification agreement between rival factions in 2015 and 2016 significantly reduced the number of homicides in the state. In that period, intentional violent deaths in the state were reduced from 46.4 to 39.8 people per thousand inhabitants – the second largest reduction in the country (FBSP, 2017). Reference Barros, Paiva, Rodrigues, Barboza and LeonardoBarros et al. (2018) explained that the brief “pacification” consisted of “proibição do ciclo de vinganças e práticas de homicídio entre grupos locais” or “prohibiting the cycle of revenge and homicide practices between local groups” (p. 118). In this brief peace arrangement, the politics of crime in Ceará, according to the authors, found support from “groups that operate in the illegal drug and arms markets on a national scale” (p. 118), such as São Paulo’s PCC and Rio de Janeiro’s Comando Vermelho (Red Command). Competing for space and legitimacy, government policies and crime policies, according to Reference FeltranFeltran (2012), have differentially governed life and death in urban territories, operating as normative regimes that people experience, also differentially, in their daily lives.

It is important to mention that organized groups making up the “world of crime” also have a “paramilitary side” (Reference MansoManso, 2020, p. 11): the aforementioned milícias. Operating primarily in the peripheries of Rio de Janeiro, milícias are groups of active or former police officers, firefighters, soldiers, and other agents that compete with drug factions for the territorial control of favelas. The favelas that are our main focus of this book, Complexo do Alemão and Complexo da Maré, are not under the influence of milícias because drug factions are the main agents of the “world of crime” in these territories. A study by the Grupo de Estudos dos Novos Ilegalismos (Group of Studies of New Illegalisms) at the Universidade Federal Fluminense claimed that the milícias challenge the state by controlling 57% of the entire geographical area of Rio de Janeiro (Grupo de Estudos dos Novos Ilegalismos, 2020). The study estimated that the milícias control more neighborhoods than drug gangs: 2.1 million of Rio’s inhabitants (or 33% of the population) live in areas under the influence of milícias, while 1.5 million (or 23.37% of the population) inhabit areas dominated by Comando Vermelho (Red Command), Terceiro Comando (Third Command), and Amigos dos Amigos (Friends of Friends) – Rio’s three main drug factions (Reference SatrianoSatriano, 2020). Like drug commands, milícias are “true businesses” (Reference Machado da Silva and Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva, 2008, p. 25). In other words, “In addition to charging for protection like the mafias, they monopolize a number of important local economic activities (alternative transport, trading gas cylinders, distribution of the signal from stolen cable TV, etc.)” (p. 25). Although criminal factions such as the PCC and Comando Vermelho have been extensively studied in academic literature, the paramilitary side of crime is relatively novel as a research object (see Reference Couto and Beato FilhoCouto & Beato Filho, 2019; Manso, 2021). In his comments about an emerging phenomenon, Reference Machado da Silva and Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (2008) posited that milícias “constitute a new type of domination by force of favelas which is less morally rejected than the domination of drug gangs. Under their intervention, residents experience a sense of personal security that disguises the coercions that they suffer” (p. 25). More than a decade after Machado da Silva presented his impressions on milícias, today it is evident that the agents of “coercions” are an additional source of repression in favelas and another actor in Brazilian politics.

In 2008, Marcelo Freixo, a progressive deputy with Marielle Franco as a cabinet member and main connection to the favelas, presided over a commission of inquiry in Rio de Janeiro’s state parliament to investigate milícias. The commission led by Freixo identified that milícias recycled old practices of “taking justice into one’s own hands,” such as the death squads described by Reference Scheper-Hughes, Comaroff and ComaroffScheper-Hughes (2006), and had reorganized themselves as private security agents. Reference CaldeiraCaldeira (2000), for example, documents that, in São Paulo, the (upper-)middle classes responded to the spike of urban violence in the 1980s by building fortified enclaves, such as gated communities and shopping malls, to segregate themselves from “crime.” Written almost a decade after Caldeira’s study, the parliament investigation report led by Freixo identified the proliferation of this segregationist model of securitization, which in part enabled the formation of milícias as agents offering security in peripheral neighborhoods. In the report’s terms, “The increase of violence, beyond that related to the illegal commerce of drugs, has yielded an obsession for security in the middle classes, which today translates into gated communities and the enthusiastic adherence to shopping centers, seen as oases of security” (ALERJ, 2008, p. 257). The legislators added that gates and barriers limiting car access had proliferated in the streets, as had offers of private security

to business owners and residents … in an informal and almost always illegal way. Under the responsibility of public security professionals, the famous “bico [side job]” is used to provide a complementary income to the very low salaries paid by the state.

And the cycle of violence in this logic of private security feeds back on itself:

The lack of control over illegal private security has reached such a point that situations have been reported where police officers are formally called in by residents and businessmen … to curb violence and end up being informally hired by the community to provide security services. And the more this service grows, the more practices of “justiçamento [taking justice into one’s own hands]” occur …

Following the conclusion of the investigations into the relations between milícias and state agents, the parliamentary commission of inquiry in Rio de Janeiro requested the indictment of “225 politicians, police officers, prison guards, firefighters, and civilians” and presented proposals to confront milícias (Reference FreixoFreixo, 2022). However, since 2008, these paramilitary groups have increased their scope of activity in Rio de Janeiro – today milícias also dispute the illegal drug trade (Reference SoaresSoares, 2022) – as well as their influence in politics. As we will discuss in Chapter 3, Ronnie Lessa, the gunman who fired the shots that killed Marielle and her driver Anderson Gomes, is a miliciano (a milícia member). At the time of Marielle’s murder, Lessa, a former police officer, was working for a milícia known as Escritório do Crime (Crime Office), led by Adriano da Nóbrega, a former member of BOPE (Batalhão de Operações Especiais; Battalion of Special Operations), the military police’s elite squad. Nóbrega had been close to the Bolsonaro family since his military days and on to his time as leader of Escritório do Crime (Reference FilhoFilho, 2022). For example, in September 2005, Bolsonaro’s eldest son, Flávio, then a state deputy in Rio de Janeiro, awarded Nóbrega with the Medalha Tiradentes (Tiradentes Medal), typically bestowed by the Rio de Janeiro parliament “to personalities who … have rendered services to the state of Rio de Janeiro, to Brazil, or to humanity” (as cited in Reference MansoManso, 2020, p. 48). But Nóbrega was given the medal while serving a preventive sentence in prison for the crimes of murder, kidnapping, torture, and extortion (Reference MansoManso, 2020, p. 49). The award to Nóbrega was part of the Bolsonaro family’s strategy to valorize torture and exceptional policing, an agenda that, in the midst of political and economic crisis, coupled with the strategic action of the global far right in digital groups, helped elect Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency and Flávio to the senate in 2018. But the connection to Nóbrega went beyond a public homage. Flávio employed Nóbrega’s sister and mother in his office for several years, and investigations indicate that both women were part of an additional corruption scheme known as “rachadinha,” whereby people were hired by the Bolsonaro family political cabinets and, without working, returned up to 90% of their salaries (Reference Barreto FilhoBarreto Filho, 2020). Fabrício Queiroz, responsible for articulating the hiring of “ghost” employees and intercepting the portions of returned salaries, was also working for the milícias, and had been a friend of Bolsonaro since their time in the army (Reference MansoManso, 2020). Given the close relations between the milícias and the Bolsonaro family, influential in the national executive, senate, and other houses of parliament, we can say that in Brazil the relationship between the “world of crime” and the state is not only one of dispute, but also of “agreements and political exchanges” (Reference Machado da Silva and MenezesMachado da Silva & Menezes, 2019, p. 531).

2.5 Favelas

In the previous sections, we described a broad state of inequality that disproportionately impacts the lives of Black Brazilians and faveladas/os. We also described the dispute (and cooperation) between “crime” and state as normative agents in Brazil, which takes place most conspicuously in favelas and peripheries, while assuming other forms elsewhere (e.g., the historical intersections between the Bolsonaro family and milícias). As we will discuss in Chapter 4, the dispute between armed agents in favelas tends to produce silence and fear among residents. Several ethnographies have documented a “code of silence” in peripheries (Reference Eilbaum and MedeirosEilbaum & Medeiros, 2016; Reference Leite and OliveiraLeite & Oliveira, 2005; Reference MenezesMenezes, 2015; Reference SavellSavell, 2021), which contextually may be instantiated as a “perennial concern about the consequences of everyday acts,” including comments about armed agents (Reference Machado da Silva and MenezesMachado da Silva & Menezes, 2019, p. 541). Based on a year-long ethnography in two pacified favelas, Cidade de Deus and Santa Marta, Reference MenezesPalloma Menezes (2015) explains that residents render this tense scenario as the experience of living in a “campo minado” or “minefield” (p. 34). This is how a favelado from Cidade de Deus described the situation in an interview:

The resident is oppressed. Look, if you live here, if you’re raised here, just because you’ve become friends with a police officer, just because you’ve given him a glass of water, the traffickers oppress you. If you’re a resident that has lived here for I don’t know how many years and got used to the drug trade and helps the dealers, the police officer will oppress you. So, you are trapped, because you have to be in the middle of everything and everyone, but not let yourself be taken by any of them. You have to be like a lamppost, you have to stay still and intact.

As the resident chronicled, the perception of territorial confinement with legal and extra-legal armed agents tends to restrict favela residents’ comments about these competing agents. In its recontextualization, a comment could be “contaminated” (e.g., be taken by the police as belonging to “crime” or by a dealer as denouncing the drug trade) and potentially yield violent effects for residents. Having “to be like a lamppost … still and intact” is an image that evokes a narrowing, rather than expansion, of the expression of positions in territories where the “fogo cruzado” (i.e., “crossfire,” or the dispute between normative regimes) most conspicuously takes place. In terms of Reference ArendtHannah Arendt’s (1958) philosophy, the code of silence is the opposite of politics, which she understands as the public negotiation and manifestation of “speech.” Arendt famously said that “violence begins where speech ends” (Reference ArendtArendt, 1994, p. 308). Our main interest in this book is precisely to investigate the sociolinguistic practice of individuals and collectives that variably project political conditions for speaking, as if following Arendt’s principle of politics depending on verbal action. The collectives that we engage in dialogue attempt to build discourse conditions to expand speech, while opposing the “code of silence” and other semiotic mechanisms that stifle faveladas/os. As these collectives also counter a historically produced stigma about the favela, we believe it is important to revisit discourses on the very invention of the favela in the nineteenth century, and the historical construction of the favela as a problem. Unpacking the sedimentation of this discourse will be key to understanding the collectives’ work of semiotic differentiation (Reference Gal and IrvineGal & Irvine, 2019).

The Invention of the Favela

Following the Brazilian monarchy’s reluctant abolition of slavery in 1888, former enslaved people and their descendants were forced to seek their own means to survive. In Rio de Janeiro, the solution found by many of them was to occupy hillsides. The emerging neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro were then called favelas, in reference to “Morro da Favela,” or Favela Hill, a monarchist settlement in the state of Bahia that resisted the newly proclaimed republic in 1889. Brazil’s military waged a campaign against the camp, resulting in the country’s deadliest civil war, also known as Canudos War (1895–1898). Some of the “soldiers returning from the war settled, with the tolerance of the army, on Morro da Providência,” a hill in downtown Rio de Janeiro that also came to be called, “in allusion to the military campaign in Bahia, Morro da Favella” (Reference GonçalvesGonçalves, 2013, p. 44).

The literary work Os sertões (Rebellion in the Backlands), written by Euclides da Cunha and first published in 1902, was fundamental to the popularization and, consequently, the presupposition of the idea of (Morro da) Favela as an anti-modern territory, located in the midst of a modernizing Brazil. This book crystallized the opposition between the coast as a synonym of development, and the backlands as epitome of a pre-modern past. Newspaper chroniclers in Rio de Janeiro, then the capital of the republic, rapidly invoked Euclides da Cunha’s work to describe the favelas that were emerging in post-slavery Rio de Janeiro. Reference Valladares and AndersonLicia do Prado Valladares (2019) exemplifies this process of textual mediation of stigma by citing a chronicle by João do Rio, published in the newspaper Gazeta de Notícias in 1908. Entitling it “Os livres acampamentos da miséria” (The open camps of misery), João do Rio reports his visit to Morro de Santo Antônio, “Which had become a favela, like Morro da Providência, during the last years of the nineteenth century.” In João do Rio’s own words:

I had the idea that Morro de Santo Antônio was a place where poor workers gathered while awaiting housing, and the temptation arose to attend the serenade. … The hill was like any other hill. A wide, poorly maintained path, on one side revealing, in layers that spread out ever, the lights of the city … I followed [the people] and came upon another world. The lights had disappeared. We were in the country, in the backlands, far from the city. The path that snaked down was sometimes narrow, sometimes wide, full of troughs and holes. On either side, narrow houses, made of planks from wooden crates, with fences indicating yards. The descent became difficult.

The author continues:

How did that curious village of indolent misery grow up there? It is certain that today it shelters perhaps more than 1,500 people. The houses are not rented, they are sold … The price of a normal house is 40–70 mil réis. All are built on the ground, without regard to depressions on the lot, with wood from crates, sheet metal, and bamboo. … One had, in the luminous shadows of the starry night, the studied impression of the entrance to the village of Canudos or the acrobatic idea of a vast, multiform chicken coop.

The chronicle “The open camps of misery” is significant because it denounces a historical accumulation, and betrays the textual mediation of this accumulation: João do Rio reported that his visit to Morro Santo Antônio struck him with “the studied impression of the entrance to the village of Canudos.” João do Rio’s scalar activity – in other words, his work making sense of the hilly neighborhood and measuring it in relation to other magnitudes – was thus mediated by communicable discourses (Reference BriggsBriggs, 2005). Drawing from his work on ideologies of language and medicine, Reference BriggsCharles Briggs (2005) puns on the medical concept of communicable diseases (i.e., affections that spread from one person to another) and proposed that discourses, while spreading across social spaces, project and legitimize ideologies of language, social processes, and persons in the world. Thus, João do Rio’s modes of predicating “another world,” the favela, as a location of “indolent misery … a vast, multiform chicken coop” was an early indication of the communicable construction of the favela as a “problem.” Further, João do Rio’s drawing from Euclides da Cunha’s naturalist and modernist account of Canudos provided his narrative with historical and scientific authority. As the medical field is often an important ground for modernist discourses, João do Rio also denounced the “filth” of these social spaces (“vast, multiform chicken coop”), while combining this sanitary comment with faveladas/os’ seeming aversion to the lights of modernity (“The lights had disappeared,” “luminous shadows of the starry night”). “The open camps of misery” is but one example of durable discourses in Brazil that conflate favelas and Blackness with bestiality, misery, and pre-modernity.

The favela became a problem in the discourses of doctors, engineers, and politicians following its invention in literary and journalistic rhetoric greatly influenced by Euclides da Cunha’s rendition of Canudos as a community without state rule whose members have a “[m]oral behavior that the observer finds revolting” (Reference Valladares and AndersonValladares, 2019, p. 100). In the 1920s, “The first major campaign against [what came to be termed as] ‘aesthetic leprosy’” was launched (Reference Valladares and AndersonValladares, 2019, p. 104), and French urban planner Alfred Agache would take up this notion in the 1930s in his plan for “renewal and beautification of the city of Rio de Janeiro” (Reference Valladares and AndersonValladares, 2019, p. 104). Reference ValladaresValladares (2000) also documented favelas’ first appearance in a legal document in 1937, with the publication of the Building Code, which “prohibits the creation of new favelas, but for the first time recognizes their existence, making itself available to manage and control their growth” (p. 12). In the following decades, favelas gradually became cemented in hegemonic discourses as a problem of public health and urban aesthetics. In 1949, the first census of favelas was conducted, consistent with Reference FoucaultFoucault’s (2007) notion of governmentality as the nexus of knowledge and power. The 1960s saw the beginning of Brazilian social science research on favelas; around the same time, researchers from abroad began traveling to Brazil to study favelas (e.g., Reference BonillaBonilla, 1961; Reference LeedsLeeds, 1969), and political initiatives such as the Peace Corps, an organization that aimed to consolidate an anti-communist agenda in poverty-stricken territories (Reference SigaudSigaud, 1995), began providing so-called assistance to favelas (Reference Valladares and AndersonValladares, 2019, p. 41).

From the “Language of Rights” to the “Language of Violence”

Until Brazil became a node for transnational drug trafficking in the early 1980s, the favela problem was treated either through segregation – several favelas were removed from the hills in central Rio and moved to the urban periphery (Reference DuncanDuncan, 2021, p. 20) – or ostensible inclusion through rights and citizenship – something strongly influenced by the struggle of social movements and Catholic grassroots work in these territories during the military dictatorship (1964–1984) and the redemocratization that followed. But as transnational drug trafficking established its retail branch in favelas, these spaces came to be seen as the source of the urban violence that increased in the 1980s. Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (2010) explains that this is the point of inflection whereby favelas would no longer be narrated through the “language of rights” but instead through the “language of urban violence”:

Nesse momento, o perigo imputado a elas deixa de ser uma questão urbanística, relacionada ao fortalecimento de uma categoria social em franco processo de incorporação socioeconômica e política. As favelas passaram a ser vistas … como o valhacouto de criminosos que interrompem, real ou potencialmente, as rotinas que constituem a vida ordinária na cidade. Em resumo, como efeito da consolidação da violência urbana, modificaram-se profundamente os conteúdos que, na perspectiva dominante, definem as favelas como um problema urbano. Sem qualquer intervenção de sua parte que justificasse essa revisão, os moradores foram criminalizados justamente quando pareciam bem sucedidos no esforço de participar do debate público.

At this point, the danger attributed to [favelas] ceased to be an urbanistic issue, related to the strengthening of a social category that was undergoing a process of socioeconomic and political incorporation. Favelas came to be seen … as the stronghold of criminals who interrupt, really or potentially, the routines that are the basis of ordinary life in the city. In short, as an effect of the consolidation of urban violence, the contents that, from the dominant perspective, define favelas as an urban problem were profoundly modified. And without any intervention on [the] part [of the upper classes] to justify a revision, residents were criminalized just when they seemed to have succeeded in their efforts to participate in the public debate.

If social movements had been able to advance rights for faveladas/os at the end of the dictatorship and the beginning of the democratic opening, in the 1980s, favelas began to be stigmatized in hegemonic discourses as responsible for the violent criminality that increasingly occupied the agenda of news media and everyday talk. Reference Machado da SilvaMachado da Silva (2010) adds:

Criminalizados e desqualificados como cidadãos de bem, os moradores sofrem um processo de silenciamento pelo qual se lhes dificulta a participação no debate público, justificando a truculência policial e … “policialização das políticas sociais.”

Criminalized and disqualified as good citizens, residents undergo a process of silencing through which their participation in public debate is made difficult, justifying police brutality and … the “militarization of social policies.”

Machado da Silva thus raised an important correlation: namely, favela residents are not only excluded from the moral construction of the “cidadão de bem” or “good citizen,” but also treated as a “problem” of “security.”

Ethnographically, we have found evidence of the historical force of these stigmatizing discourses at the core of the idea that favelas are a problem to be securitized. For example, in 2013, Daniel participated in a focus group with young residents from Vila Cruzeiro, a favela contiguous to Complexo do Alemão. The group was gathered by Verissimo Júnior, a high school teacher and founder of Teatro da Laje (Rooftop Theater), a theater collective that aimed at projecting an positive view of favelas. The following excerpt illustrates a moment in the debate when participants were talking about police duras, a slang term that designates harsh approaches to policing, both communicatively and physically. Luan, a young Black man from a middle-class neighborhood, had asked participants to comment on duras they had experienced or heard about. The conversation seems to summarize the description above of the stigma against faveladas/os and some of its effects:

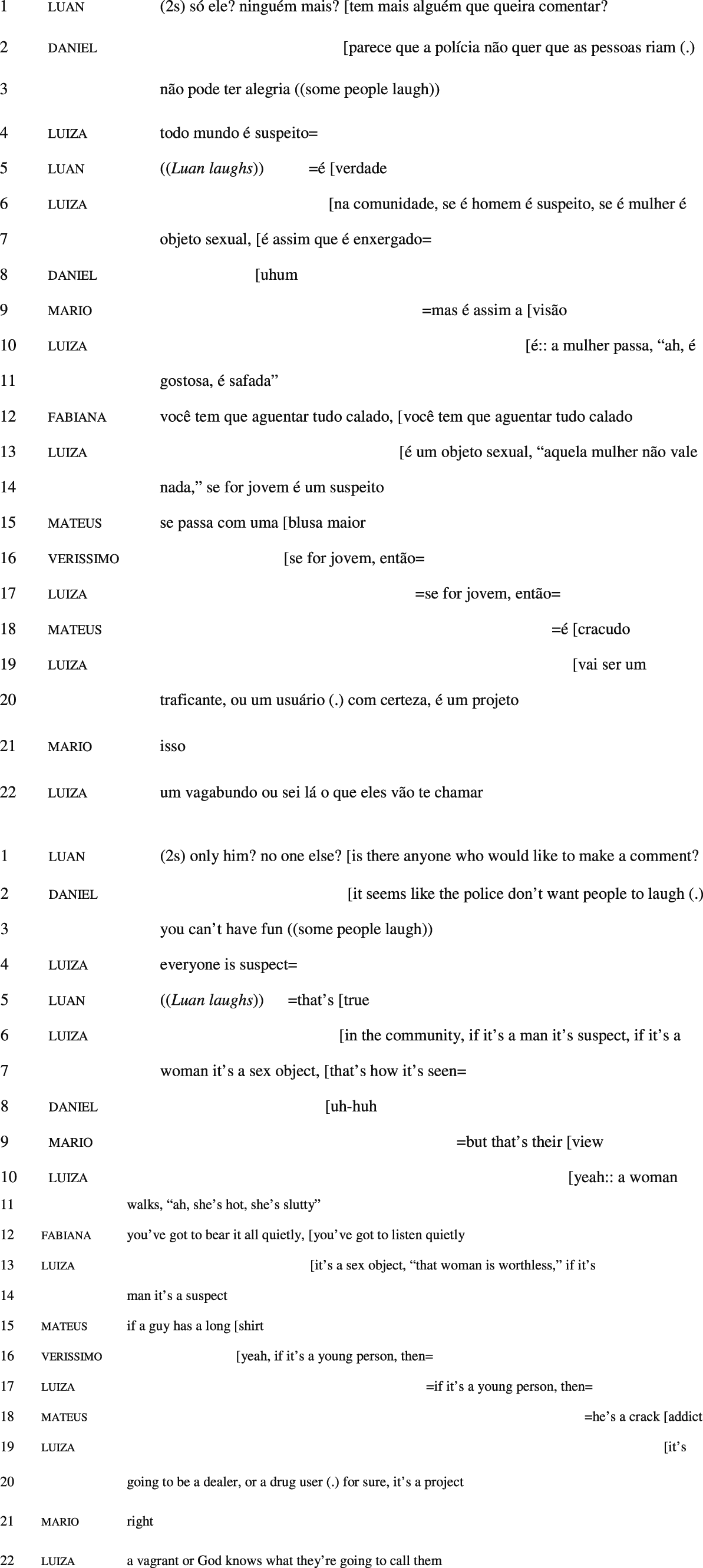

Excerpt 2.1 Focus Group, Grupo de Estudos Culturais, Vila Cruzeiro, 2013

The youths, Verissimo, and Daniel collectively described stereotypical comments on signs of identity and language of faveladas/os. After Luan solicited further responses to his question about duras in favelas, Daniel jokes about the police not wanting people enjoying themselves in favelas (lines 2–3), and Luiza comments that in the favela, especially if one is male, one is likely “a suspect,” or if one is a female, she may be framed as “a sex object,” identifying potential victims of police or gender violence, respectively. In her examples, Luiza was very likely iterating the essentialist moral opposition between “cidadãos de bem” and “bandidos,” at the core of securitizing discourses. As Reference FeltranFeltran (2011) comments, “bandidos” does not name only “those practicing acts considered illicit, but, in many situations, also those who look like bandidos in the social stigma … that is, young people, residents of peripheries and favelas, who dress in such a way, who carry such objects, who speak in such a way, in addition to their families and networks of close relationships” (p. 316). The young focus group participants demonstrate the referential flexibility of the term bandidos: Mateus says that “if a guy a long shirt, he’s a crack addict” (lines 15–18), and Luiza declares that “if it’s a young person, it’s going to be a dealer, or a drug user … or a vagrant” (lines 19–20).

In line 12, Fabiana addresses “the code of silence” more prominently: in the midst of the collaborative depiction of stigmatization and duras, she says that “you’ve got to bear it all quietly, you’ve got to listen quietly.” Yet, as we are concerned with the practical method of hope whereby activists and residents reorient knowledge (Reference MiyazakiMiyazaki, 2004), this focus group itself, promoted by Verissimo Júnior, a teacher with a clear progressivist agenda, may be seen as a participant framework where the code of silence and the denial of political participation for faveladas/os is reoriented. Collectively, the youth in the focus group unpack the stigma while participating in an event advancing more affirmative views of the favela. As participant frameworks are not isolated events but nodes of discourse chains (Reference AghaAgha, 2007), the critical semiotic constructions in the above conversation could, through further semiotic work, travel to other events (Reference Bauman and BriggsBauman & Briggs, 1990) and contribute to the construction of alternative ideological perspectives (Reference Gal and IrvineGal & Irvine, 2019) to the criminalizing discourses we have discussed. This kind of semiotic work is foundational to the collectives we focus on in this book, which we present below.

2.6 The Collectives

Instituto Raízes em Movimento

The Instituto Raízes em Movimento (Roots in Movement Institute) is an NGO formed by Complexo do Alemão residents in 2001. The activists in this collective work on two fronts: “knowledge production” and “communication and culture” (Instituto Raízes em Movimento, 2016). On the former front, Raízes has created the Centro de Estudos, Pesquisa, Documentação e Memória do Complexo do Alemão (Complexo do Alemão Research, Documentation and Memory Center, CEPEDOCA), responsible for fostering research about Complexo do Alemão (necessarily involving researchers from favelas), documenting the existing knowledge about Complexo do Alemão and other favelas, and developing courses and events that facilitate the construction of knowledge about favelas. On the communication and culture front, the collective has promoted various courses, events, and cultural strategies to stimulate cultural production in the favela and more expansive forms of dialogue between faveladas/os. Raízes has also partnered with universities, NGOs, and various institutions to promote courses on history and memory of favelas and documentary production. Faveladoc, for example, is a workshop on documentary filmmaking for young faveladas/os that culminates in the making of a documentary on a topic of interest to the favela, such as the impact of the megavents, as seen in “Copa pra Alemão ver,” or “World Cup for the Gaze of Germans” (see Instituto Raízes em Movimento, 2014), and AfroBrazilian religions in “Quando você chegou, meu santo já estava,” or “When you arrived, my saint had already been here” (see Faveladoc, 2019).

Raízes has also been our main collaborator in the field. Since 2012, Daniel’s field visits have been mediated by Raízes activists, who enthusiastically welcomed the research project “Cultural mapping of cultural production and literacy practices in 3 favelas of Complexo do Alemão, RJ.” Written by Adriana Facina (Museu Nacional, UFRJ), Adriana Lopes (Instituto de Educação, UFRRJ), and Daniel, the research project lasted from 2012 to 2015, and enabled his participation in various activities hosted by Raízes in Complexo do Alemão. Daniel has continued his interaction with activists, residents, and other researchers in Complexo do Alemão, and since 2021, Raízes activists have collaborated with Daniel and Jerry’s current project, including through transcription and discussion of data and theory with us. Much of the data analyzed in this book was generated in activities promoted by Raízes, including Circulando: Diálogo e Comunicação nas Favelas – an annual event that combines an open-air fair and discussions at the seat of Raízes on Avenida Central in Complexo do Alemão (or online, during the restrictions for physical meetings during COVID-19) – and the “Vamos Desenrolar” course, a series of talks and conversation circles involving residents, activists, and researchers. Communicatively, in line with the enregisterment of papo reto that we discuss in Chapter 4, the initiatives of Raízes em Movimento have aimed to “estabelecer o diálogo, a conversa, o ‘desenrolo’ com todos os presentes que queiram se pronunciar,” or “establish dialogue, conversation, the ‘desenrolo’ [the unroling of the lines of talk] among all those present” in the events (Instituto Raízes em Movimento, 2016, n.p.). In other words, Raízes is an institution promoting participation frameworks and conditions for communicative practices that, in defiantly speaking to “point,” challenge the “code of silence,” cordial racism, and inequalities narrated above.

Instituto Marielle Franco

As we discuss in Chapter 3, in 2018, our work with favela activists was crucially impacted by the assassination of Councilor Marielle Franco. A personal friend of Adriana Lopes and Adriana Facina and part of the extended network of activists connected to Daniel, Marielle Franco was born in Complexo da Maré, a group of favelas contiguous to Complexo do Alemão. As we write this book, over four years after her assassination, the person or the group who commissioned the murder of Marielle and her driver Anderson Gomes is still unknown. This tragic event has been crucial to Brazilian politics far beyond the progressive sectors where Marielle built her influence. Under Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far right invoked Marielle’s figure as an icon of the “perversion” of the left, the enemy against which Bolsonaro’s conservative, anti-gender, and anti-communist crusade gathers traction (see Reference CesarinoCesarino, 2020; Silva & Dziuba, 2023). On the left, Marielle appears as a figure of present immanence (Reference Silva and LeeSilva & Lee, 2021; Reference Khalil, Silva, Lee, Makoni, Kaiper-Marquez and MokwenaKhalil, Silva, & Lee, 2022). As part of the transnational movement of struggle for justice that has emerged following Marielle’s murder, her family – namely, Anielle Franco (her sister), Luyara Franco (her daughter), Monica Benicio (her partner), Marinete da Silva (her mother), and Antônio Francisco da Silva Neto (her father) – established the Instituto Marielle Franco. In line with the sociolinguistic imaginations and metaleptic temporality that we are dedicated to describing throughout this book, the declared mission of the Instituto is to “luta[r] por justiça, defende[r] sua memória, multiplica[r] seu legado e rega[r] suas sementes,” or “fight for justice, defend [Marielle’s] memory, spread her legacy, and water her seeds” (Instituto Marielle Franco, 2022, n.p.).