1 Introduction

There is a fundamental, eternal and unresolvable conundrum at the heart of customary international law (CIL) – the ‘source’, if the pun may be excused, of the enigma that is customary law. It is that we do not know on what we can – or are allowed to – base our arguments for or against one or another concept. Authors frequently note the lack of discipline in our debates on the foundations of this source of international law, even as they fail to show any themselves. Plenty of old wine is poured into new bottles as we seem to periodically rediscover arguments which generations upon generations before us have made – sometimes all the way back to Roman law.

Debates on the theory of CIL continue unabated, inter alia because there is a continuing, strong, urgent and foundational belief that we need CIL in order to keep international law working. Instead of being able to see customary law as a primitive method of norm-creation which is severely limited in its utility and dismissing it – as their domestic colleagues are wont to do – as entirely unsuitable for modern legal orders which tend to be complex and technocratic, an important sub-group of international lawyers wish to see and/or create international law as such a complex legal order. To this group belong practitioners and international legal scholars with a stake in the actual functioning of the law. They imagine customary law to be capable of performing the complex functions analogous to legislation in domestic law.Footnote 1 They do so not out of a sense of pride or ego, but because they genuinely believe that we cannot rely on treaties alone, that we must have CILFootnote 2 (and therefore do) in order to achieve the political goals international society or politics needs to progress (or those which they imagine do). But the question is whether that is reason enough to consciously or subconsciously change the mechanics of customary law to suit these perceived needs and whether CIL has the flexibility to react to these perceived needs.

Two events have prompted my writing of this chapter. The first is that the International Law Commission (ILC) concluded its project on the Identification of Customary International Law in 2018.Footnote 3 Ably directed by Michael Wood, it has from the very beginning been suffused with the spirit of pragmatism. The project primarily wanted to provide guidance to decision makers, particularly those not professionally trained in international law. Engaging in depth with the theory of CIL was consciously avoided as far as possible. Yet, for all its self-avowed pragmatism, the ILC could not avoid taking a stance on the theoretical aspects of this source, even if only in a roundabout, subconscious manner. On the other side of the equation we find foundational critiques of CIL, with Jean d’Aspremont’s 2018 International Law as a Belief System as well as recent articles on CILFootnote 4 as excellent recent contributions to this genre. In these writings, CIL is downgraded to a set of doctrines within the canon of folk tales international lawyers tell themselves – our ‘bed-time stories’, so to speak.

Both methods have virtues, but both have very dangerous vices and both, in a sense, contain the seeds of their own destruction. One aim of this contribution will therefore be an effort to show the relative merits and demerits of these two approaches, exemplified in the ILC Report and d’Aspremont’s work. I will focus on what they can tell us about the theoretical foundations of customary law as a source of international law. I am sympathetic to both: CIL is on shakier ground than mainstream writers and practitioners assume, but the point cannot be to employ a brutal reductivism. In this chapter, I will show where the quicksand lies and why our reliance on this source is problematic. To paraphrase Carl Schmitt: whoever invokes customary international law wants to deceive.Footnote 5

The second event to spark this chapter is that at the time of writing fifteen years had passed since I first published an article in the European Journal of International Law on the fundamental ‘uncertainties’, as I called them, of customary international law-making.Footnote 6 This anniversary and the conclusion of the ILC project have prompted me to rethink the argument made then and to reconceptualise the foundation of this source whose importance for international lawyers is eclipsed only by their frustration in the face of the manifold aporia with which they are confronted when wishing to research and/or apply it. My work usually stops at the recognition that we cannot find the law which tells us what the rules on customary international law-making are. In this chapter, I will attempt to go a step further.

Accordingly, Section 2 will summarise what I consider to be the salient features of the two approaches, exemplified by the writings of its two champions, Wood for the pragmatists and d’Aspremont for the iconoclasts. This section is brief because these traits are better discussed using specific examples. Indeed, the example in Section 3 is the pivot point for this chapter, because it is both an illustration of the two approaches as well as an expression of the high-level problem: the ‘meta-meta law’ and the problem of finding what its content is. Section 4 will focus on this problem and will discuss my proposal for a new method for conceptualising this elusive level.

2 Two Approaches to Customary International Law

There are, of course, more than two possible approaches to customary (international) law and the choice of these two is arbitrary. Yet, they are well-known and well-respected archetypes for two essential directions the debates on this topic have taken in the past decade or so – both in terms of the sharp divergences that characterise them as well as the fact that they are surprisingly close on some points. Wood is typical of those scholars and practitioners who wish to construe CIL in a practicable manner from a ‘generalist’ perspective; d’Aspremont is the most adept communicator among the younger generation of scholars who seek to deconstruct the theoretical-philosophical foundations of the stories we tell about custom. Both approaches have merits, but both suffer from significant defects: Wood is right to focus on the positive law, but wrong to dismiss CIL’s problems so easily. His generalist-pragmatic understanding leads to an indistinct view of what CIL is and how it comes about; an impish soul might call him ‘the astigmatic pragmatist’. D’Aspremont is right to criticise that aspect, but the way forward in legal scholarship cannot lie in a reduction of law to collective psychology; he, in turn, could be called a ‘frustrated iconoclast’. My argument is, and has been for more than fifteen years, that both methods have a point, but that we require a combination of factors in order to make headway in international legal scholarship on customary law: it should be a theory-conscious analysis of the positive law in force.

2.1 Astigmatic Pragmatists

From the beginning of the ILC’s project on CIL, Michael Wood as the special rapporteur was committed to pragmatic goals, rather than to exploring theoretical (or even many doctrinal) questions. Wood’s First Report is clear about the project’s goal, namely ‘to offer some guidance to those called upon to apply rules of CIL on how to identify such rules in concrete cases’,Footnote 7 that is ‘especially those who are not necessarily specialists in the general field of public international law’, because it is ‘important that there be a degree of clarity in the practical application of this central aspect of international law, while recognizing of course that the customary process is inherently flexible’.Footnote 8 On that pragmatic level, concerned with the ‘usefulness of its practical consequences’,Footnote 9 the project has to some extent succeeded. In this sense, the ILC’s work has a stabilising function and Wood is to be commended for his contribution. If he had remained on this pragmatic level, it would not have made for a good example for this chapter; however, there are indications that there is more to this mindset. For example, in a 2016 article, Wood (writing in his private capacity), argues: ‘Work on the topic has also shown that several longstanding theoretical controversies related to customary international law have by now been put to rest. It is no longer contested, for example, that verbal acts, and not just physical conduct, may count as “practice.”’Footnote 10 One can take issue with statements such as this on several levels. For one, it is less than certain that ‘theoretical controversies’, including the verbal practice problem, have been ‘put to rest’ (which itself can mean a number of things). On another level, however, I submit that this type of statement is indirectly expressive of a particular view popular with practitioners and practice-leaning scholars, mistakenly believing that practice solves theoretical problems. While neither Wood nor the ILC texts openly declare it, one could argue that there is a subconscious belief that the eternal problems of customary law can be solved by the Commission declaring one side the winner – or that it should try. It is trivial to say that the ILC is not a lawmaker which could modify the law on customary international law-making. It is perhaps not so trivial to say that the role of the ILC as epistemic ‘authority’ – as an institution whose pronouncements can be presumed to accurately represent the state of international law – is equally problematic, particularly given the narrow range of sources and arguments on which it, like most orthodox international lawyers, relies.

Partially, this can be explained by the peculiar, if widespread use of the word ‘theory’ in English legal language. Whereas for example in German, Theorie or Rechtstheorie refers to legal theory, in English it tends also to be used for doctrinal statements about the material content of the positive law. The ‘theory of customary international law’ of which Wood writes tends to be concerned with questions like the relative value of domestic court judgments as state practice or the requisite number of instances of opinio juris.Footnote 11 Those are not the core research areas of legal theorists, but of international legal scholars – Rechtsdogmatik in German. If those topics are ‘theory’, then it is not surprising that legal theory properly so called finds no place in the ILC project and that a pragmatic project assumes that it has made changes to the ‘theory’ of customary law.

Largely, however, it is the culture of orthodoxyFootnote 12 which moulds this mindset. Orthodoxy is understood here as respect for conventional authority (acceptance by peers). International lawyers with their largely (but not consistently) ‘positivist’ outlook tend to exhibit three elements as part of the culture of orthodoxy: (1) submission: international lawyers submit to an apology of international tribunals (foremost the ICJ) as almost unquestioned authorities; (2) realist pragmatism: the pragmatic impetus unites with a belief in being ‘realistic’ and accommodating the ‘realities’ of international life, particularly practice – we know that practice is relevant because practice tells us that practice is relevant; (3) problem-solving: their pragmatic bent leads naturally to a tendency to try to solve problems, rather than analyse the law, even when they are not authorised to ‘solve’ the problems themselves.

On this basis, Wood’s reports combine a certain (small-c) conservatism on substantial issues, for example on international legal subjectivity,Footnote 13 with a pragmatic modus operandi. As mentioned above, the problem arises when there is even the tacit assumption that this is the right way to cognise or change the law – the result is an unclear cognition, an astigmatism.

2.2 Frustrated Iconoclasts

Like myself, Jean d’Aspremont has critiqued the naïveté inherent in the ILC project, which cannot escape the theoretical problems of what he calls the ‘monolithic understanding of customary law’.Footnote 14 This is obvious in manifold ways, including the central problem of verbal practice which we have both criticised in similar terms. His is a theoretical approach to (customary) international law; it is heterodox in the sense that theoretical coherence is more important to him than his arguments being in line with what is generally accepted. However, even the briefest look at his current theory, summarised in the 2018 book International Law as a Belief System, shows that its radical reductivism borders on non-cognitivism and threatens to destroy more than false assumptions. In this book, d’Aspremont argues with some justification that much of the (orthodox) discourse about what CIL is and how it functions – ‘the articulation of international legal discourses around fundamental doctrines’, as he puts it – has the hallmarks ‘of a belief system’.Footnote 15 That, in turn, is characterised in the following manner:

[A] belief system is a set of mutually reinforcing beliefs prevalent in a community or society that is not necessarily formalised. A belief system thus refers to dominant interrelated attitudes of the members of a community or society as to what they regard as true or acceptable or as to make sense of the world. In a belief system, truth or meaning is acquired neither by reason (rationalism) nor by experience (empiricism) but by the deployment of certain transcendental validators that are unjudged and unproved rationally or empirically.Footnote 16

The ‘fundamental doctrines’, such as (our talking about) CIL are ‘organised clusters of modes of legal reasoning that are constantly deployed by international lawyers when they formulate international legal claims about the existence and extent of the rights and duties of actors’,Footnote 17 which sounds reasonable as a sociological description of the language use by international law professionals. And indeed, on first blush, d’Aspremont seems to carefully guide us through the problems of this deconstructive enterprise. This new view of customary law doctrine as part of a belief system and as a cluster of reasoning is supposedly a ‘heuristic undertaking’ ‘with a view to raising awareness about under-explored dimensions of international legal discourse’. By this method, he posits the possibility of ‘a temporary suspension of the belief system’ and ‘a falsification of the transcendental character of the fundamental doctrines to which international lawyers turn to generate truth, meaning or sense in international legal discourse’.Footnote 18 In more conventional terms, by realising that the (dominant) way in which we talk about international law and the widespread acceptance of certain doctrines does not equal ‘truth’, the authority of orthodox assumptions can be questioned. So far so good: questioning the unspoken assumptions of legal scholars is the main task of all legal theory and I would happily count myself among those who participate in this form of ‘radical’ critique in the word’s original sense: pertaining to the radix, the root or foundation, of our knowledge.

Yet at this point the critique turns to iconoclasm, despite d’Aspremont’s avowed aim of avoiding ‘apostasy’, which ‘is neither possible nor desirable’.Footnote 19 Let us look at what d’Aspremont does not (wish to) talk about: international law itself and the relationship of the doctrines/belief system to the body of rules/norms that is the law. The open question is as to the reason for this reluctance, which he shares with many other postmodernist international legal theorists. My interpretation of this peculiar state of affairs – peculiar from my theoretical vantage point – is that for d’Aspremont, two foundational beliefs strongly discourage talking about the law itself in any meaningful way: (1) a general noncognitivism; (2) a specific aversion to the ‘ruleness of sources’.

(1) For d’Aspremont, the title of his book is enough to show the radical reductivism of this strain of thought: it is international law that is a belief system. Despite considerable vacillation between the possibility of rules/norms and their denial, in the end, international law is identified with and reduced to ‘law-talk’ – the way we talk about the law is the law. The ‘existence’ in any sense of the word of international law as body of rules (as legal order) is half-negated. It seems – although it is difficult to pinpoint in the text – that, on the one hand, substantive rules are rules properly speaking, but on the other hand, sometimes certain parts of the law and the law in general is doctrine. Law is doctrine, law is a socio-psycho-linguistic phenomenon, law is reducible to (a special kind of) facts and apprehensible only by social-scientific methods. Even when d’Aspremont’s approach was still closer to Hartian legal positivism, it tended to favour reductivist, legal realist and anti-metaphysical readings of Hart.Footnote 20 With this book, this trend is strengthened and he is now closer to the postmodernist orthodoxy in international legal theory.

(2) Denying the idea that the law regulates its own creation (i.e. sources sensu stricto), and that sources are not themselves law unites certain post-Hartian and postmodernist theoretical approaches with a long tradition of state-centred thought in international legal doctrine. Whereas the former would rather, as d’Aspremont does, reduce sources to a doctrine – to teachings and to methods of law ascertainmentFootnote 21 – the latter see the source of law immediately founded in facts.Footnote 22

The problems which this approach engenders are, at least potentially, destructive not just of false orthodox narratives, but of the very idea of law. It does not really matter that d’Aspremont asks us only for ‘a temporary suspension’Footnote 23 of the belief system. The very possibility that we can simply suspend belief destroys the underlying concept and is probably self-contradictory – as if we could temporarily suspend belief that half, but not all, of the audience members are in an auditorium. Reductivism of this sort must face up to the enormous problem that it cannot distinguish between the belief system of doctrines about the law and the possibility that the law itself is no more than a belief system. This idea is indeed more than a heuristic tool to critique baseless orthodox taboos and fetishes, it is more than ‘apostasy’; it negates the very possibility of law as something separate from what actually happens in the physical world, its counterfactual nature. ‘The argument that in the end … the “existence” of law “is a matter of fact” is a negation of the very possibility of Ought. Ideals cannot be deduced from reality alone.’Footnote 24 It does not really matter that perhaps the reductivism which d’Aspremont wishes to promote is not anti-norm-ontic, merely epistemic. As long as the mediatisation of law by way of beliefs and discourse is watertight, law is still reduced to facts. If we adopt such reductivism, we are throwing the baby (the notion that ‘you ought not to kill’ makes sense as a claim to regulate behaviour) out with the bathwater (the true observation that many of our most cherished doctrines have little to do with the content of the positive law). But there is some ‘hope’ that orthodoxy’s serene pragmatism will domesticate and ultimately frustrate this iconoclasm – as it tends to do with all theoretical arguments, whether they are right or wrong.

3 Verbal Practice as Example

How do the two approaches deal with an issue which is not always acknowledged as problem, but which (from a theoretical vantage point) is far from problem-free? From a range of potential topics I have chosen verbal practice, because it allows me to demonstrate the strengths and weaknesses of both approaches introduced in Section 2 – but also because it is an ideal candidate to show the fundamental problem of all CIL theory (Section 4).

Verbal acts have become incredibly important for international law and we have increasingly turned to texts to support our claims to the emergence, change and destruction of customary law. That is because our world has become more complex whereas customary law as ancient law-creation mechanism originally based on raw actions has not. The classical controversy about the role of verbal utterances as practice has abated and it is virtually universally admitted that statements can be state practice.Footnote 25 In customary international humanitarian law, for example, reliance on verbal practice has far eclipsed ‘battlefield practice’ – take the ICRC study’s almost exclusive use of verbal emanations such as manuals as example for this trend. For example, the ‘Practice’ section for the principle of distinction contains a vast amount of material. As far as I can tell, all of these are statements and not a single instance of battlefield practice is mentioned;Footnote 26 for example under ‘Other National Practice’, the study quotes the following ‘“[i]t is the opinio juris of the United States that … a distinction must be made”’ – opinio juris is thus made practice. The entire project seems to be aimed at reporting statements, rather than acts.

The pragmatic temperament of colleagues has meant that they are unwilling to exclude any factor that might possibly be useful. Accordingly, verbal acts are now universally recognised, including by Wood. He is dismissive of those who problematise the use of statements; those ‘views … are too restrictive. Accepting such views could also be seen as encouraging confrontation and, in some cases, even the use of force.’Footnote 27 That is a strongly emotive argument – you better accept verbal practice or we may end up at war – but in terms of a dispassionate legal argument it cannot convince. Yet orthodoxy’s pragmatic impetus pushes Wood and the ILC to focus on the fact of widespread acceptance by peers:Footnote 28 “it is now generally accepted that verbal conduct … may also count as practice.”Footnote 29 The only substantive argument is negative; Wood quotes Mark Villiger’s 1997 monograph, which contains the following argument: ‘the term “practice” … is general enough … to cover any act or behaviour … it is not made entirely clear in what respect verbal acts originating from a State would be lacking’.Footnote 30 Neither argument is particularly strong. Why, on the one hand, should general acceptance by peers be a decisive factor in the creation or cognition of law? Cognition is not a matter for plebiscites; scholarship is not a dictatorship of the majority. This argument has pragmatic value – it is difficult to argue against it, certainly – but is weak in terms of scholarship. On the other hand, a whole school of thought in the classical debate on verbal practice has made it its business to set out what, exactly, this form of practice is ‘lacking’; we are, I think, not really confronted by a dearth of argument against verbal practice.

And, indeed, there are two (partially overlapping) avenues to problematising verbal practice: one is doctrinal and another theoretical. D’Aspremont’s critique is, I submit, rather on the doctrinal than the theoretical side. When he argues that ‘the International Law Commission’s formal acceptance that practice and opinio juris can be extracted from the very same acts collapses the distinction between the two tests’,Footnote 31 I would argue that he is more concerned with a question of language-use, whereby we do not keep apart the two elements and the evidence for them. As I argued in my 2004 article (and as is obvious by the ICRC counting a clear instance of opinio juris as practice), the word ‘practice’ seems to lead a double life.Footnote 32 Villiger, in another section of the monograph mentioned above, gives us an indication of this double meaning. When he argues that those denying the validity of verbal acts ‘cannot support their views on State practice with State practice’,Footnote 33 a critical reading would see him commit a circular argument; on a more charitable reading, however, it is obvious that the two meanings of ‘state practice’ differ markedly.

The most common use of the word ‘state practice’ is wide. Discussing the special problem of treaties as state practice, Villiger notes that ‘the acceptance of a convention[’s] … significance as State practice, namely as an expression of opinio juris, is lessened for three reasons’.Footnote 34 Quoting another classical author, Michael Akehurst puts it to us that ‘State practice means any act or statement by a State from which views about customary law can be inferred’.Footnote 35 We can see that state practice on this reading can express opinio juris; it can be the basis for inferences to what states believe to be the state of customary law. I believe that there is a conceptual (but still doctrinal) case to be made that we need to distinguish between evidences/proofs of custom-forming elements and the elements themselves. Critics are certainly right that this commingling almost inevitably leads to problems. I join d’Aspremont, however, in arguing that – on this level – the problem is more practical and more a question of internal incoherence of the orthodox position:

[T]he Special Rapporteur, while showing some awareness for the problem of double counting, had no qualms defending the idea that practice and opinio juris could be extracted from the very same acts. … it must be emphasized how difficult it is to reconcile the claim made in Conclusion 3 that each of the two elements must be verified separately with the explicit possibility that practice and opinio juris may be extracted from the same acts.Footnote 36

As pragmatic argument, however, this line of critique is liable to be rebuffed by equally pragmatic assurances that in practice this does not matter and will not be problematic: ‘distinctions between “constitutive acts” and “evidence of constitutive acts” … are artificial and arbitrary because one may disguise the other’.Footnote 37 Wood’s equivocating between his insistence on the separation of the two elements and his willingness, to admit ‘state practice’ as evidence of opinio jurisFootnote 38 is borne of that pragmatic impulse. Nothing would be easier than to give in to the idea that we could just ‘take some scholars’ use of the term “state practice” with a pinch of salt’.Footnote 39 This ‘state practice’, as it were, is merely a slightly inaccurate use of the word, given that ‘state practice’ is also the technical term for the objective element of customary law creation. ‘State practice and opinio juris may be categorically different things, but we may look for proof of either element in the same place’Footnote 40 – problem solved.

However, these pragmatic manoeuvres hide the real theoretical problem which only the second avenue of critique is able to clarify. Neither the orthodox international lawyer nor the ‘international law as argumentative practice’ theory espoused by d’Aspremont and others – the ‘post-ontological … mindset’Footnote 41 – are likely to be able to distil the fundamental legal theoretical problem of verbal practice. The classical canon of generalist international legal writings is once more on point. I stillFootnote 42 believe that Karol Wolfke’s argument expresses the true theoretical problem of verbal practice, whether or not a theoretical, rather than doctrinal argument was intended. For him, admitting verbal practice ‘neglects the very essence of every kind of custom, which for centuries has been based upon material deeds and not words. … customs arise from acts of conduct and not from promises of such acts’.Footnote 43 Wolfke is correct: the utterance ‘I will do x’ does not mean physically doing ‘x’: ‘repeated verbal acts … can give rise to international customs, but only to customs of making such declarations, etc., and not to customs of the conduct described in the content of the verbal acts’.Footnote 44

The theoretical basis for Wolfke’s argument is that at least in the civil tradition of customary law, despite just about everything being contentious about this source, one thing is reasonably clear: customary law must be based on customs. Customs, usus, actus frequens,Footnote 45 in turn must be an observance of the budding prescription or exercise of the budding right. Without the manifestation in a behavioural regularity of what will become binding, there can be no usage; without usage, the law-making of unwritten laws is not customary law. Customary law must be about customs. It is predicated on customs being or becoming obligatory. Only the behaviour that is (or is to become) the content of the norm – the ‘practical exercise of the legal rule’Footnote 46 – can serve as the objective element. Only doing or abstaining from ‘x’ can count as usus for a customary norm which prescribes ‘x’. Talking about doing/abstaining from ‘x’, in contrast, can be content forming only for a norm which prescribes talking. For norms which specify actual behaviour, none but actual behaviour will do as usus. With respect to state practice, the prohibition of torture is not constituted by states saying that they will not torture, only by the actual omission of torture. Customary law is a primitive form of law-making and cannot do all we ask of it in modern international legal debate.

The force of this argument is not undermined by the theory of speech acts.Footnote 47 Sometimes, speech can be more than descriptive: ‘I name this ship “Queen Victoria”’ or ‘I now pronounce you man and wife.’ One could therefore argue that verbal state practice is largely composed of such acts – the content, rather than the fact of uttering, is determinative. In certain cases, this may be true: it is conceivable that there are customary norms whose usus is a series of speech acts. However, not all speech is speech acts and this supplanting cannot happen for all, or indeed, for most legal rules. For example, ‘I am putting a chicken in the oven to be roasted’ is not a speech act; what is more, the chicken will firmly remain on the kitchen counter once I have uttered the sentence. The putting of the chicken into the oven can only happen in the real world; only when I have physically moved the chicken from the kitchen counter to the oven will the sentence be true. The same applies a fortiori to the usus with respect to customary norm-creation: uttering the words: ‘we are not torturing’ is not a speech act, but a (possibly accurate) description of the behaviour by state organs. It is not the actual omission of torture and – even if we accept the theory of performative utterances – cannot replace it as usus/actus frequens in the process of custom-formation for a norm regulating actual behaviour, as the prohibition of torture is.

However, this argument is predicated on customary (international) law being a type of norm that has two essential criteria: (1) the creation of customary norms requires a repetition of behaviour; (2) this behavioural regularity – the sum-total of behaviours attributed to the law-creation process – is the content of the prescription (Tatbestand) of the norm. Yet how do we know that this is the legally correct predicate? The concept of customary (international) law is not unitary, as d’Aspremont points out for international legal doctrine.Footnote 48 There are strong currents, from Roman law all the way to the drafting of the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) Statute in 1920, of a different basis for customary law: ‘acts … of a specific kind were … considered as custom-creative … only, because these acts evidenced the consensus tacitus in an adequate form’,Footnote 49 writes Siegfried Brie; the PCIJ/International Court of Justice (ICJ) Statute speaks of ‘a general practice accepted as law’. There are, however, also strong indications that over the course of the development of western (particularly civil) law, usus understood as behaviour which forms the content has been regarded as essential for the very idea of customary norms. Yet, even if we ignore countervailing arguments made over the course of the more than 1,500 years of our debating customary law, the legal-structural question remains: why is this the correct (or incorrect) reading of what customary (international) law is? On this level, we cannot effectively counter the orthodox insistence that verbal practice is part of state practice because it is accepted by all those who matter with the essentialist argument that customary law is necessarily shaped in a specific manner which conflicts with the majority opinion. That would mean succumbing to a metaphysical realism. If we do not wish to absolutise and reify concepts such as this, we must at least admit that this source of law could be different. Bin Cheng’s proposal to rename customary international law to ‘general international law’ once he eliminates practice from the conditions for law-creation, is consistent.Footnote 50 Whether CIL is different, however, is a question for the meta-meta law (Section 4).

4 Source-Creating International Law?

4.1 Law-Identification versus Law-Making

Therefore, as mentioned above, I strongly believe that on a truly legal-scholarly (rather than pragmatic) perspective, the real problem is the exact content of those rules which regulate the creation of CIL. Yet, instead of tackling it head-on, recent writings on CIL, the ILC project among them, engage in what looks to me like an exercise in avoidance: they speak of customary law ‘identification’ or ‘ascertainment’. Law-creation, not to mention the law of law-creation, is not discussed. This is understandable, given the widespread feeling among international lawyers that attempts at solving the problems of customary law have been unsuccessful, also given their resignation that they can ever be solved. Focusing on law-identification may seem like a legitimate alternative, particularly on the basis of the success of anti-metaphysical, radically reductivist and non-cognitivist Anglo-Saxon (legal) philosophy; d’Aspremont’s ‘post-ontological … mindset’.Footnote 51

Take the ILC project. The 2018 ILC Conclusions open with the bold statement that they ‘concern the way in which the existence and content of rules of CIL are to be determined’;Footnote 52 the commentary explains that the conclusions ‘concern the methodology for identifying rules of CIL, seeking to ‘offer practical guidance’ regarding this determination, which, in turn, means that ‘a structured and careful process of legal analysis and evaluation is required to ensure that a rule of customary international law is properly identified’.Footnote 53 For the ILC, the objective and subjective elements, state practice and opinio iuris, respectively, are identification elements: ‘to identify the existence and content of a rule of customary international law each of the two constituent elements must be found to be present’: ‘practice and acceptance as law (opinio juris) together supply the information necessary for the identification of customary international law’.Footnote 54 The ILC conclusions explicitly do not wish to address law-creation, which is seen as different from law-identification: ‘Dealing as they do with the identification of rules of customary international law, the draft conclusions do not address, directly, the processes by which customary international law develops over time.’ Yet the ILC seems to distance itself from law-creation properly (ie legally) speaking even in its disavowal. The ‘consideration of the processes by which [customary international law] has developed’, the ‘formation of rules’Footnote 55 which the ILC does not want to look at, seems to be one of the social or socio-psychological forces at play in physical reality, matters usually studied by legal sociologists, rather than legal scholars sensu stricto.

This raises a number of issues concerning both internal coherence and external justification. I have italicised a number of phrases in the previous paragraph to indicate some of the issues, for example the incoherence of arguing that it is a methodology, yet that we should follow them not merely to ensure proper ‘identification’ or ‘determination’ (a sort of ‘correct cognition’), but also qua rules to be followed: ‘as in any legal system, there must in public international law be rules for identifying the sources of the law’.Footnote 56 This seems to be belied by the project’s aim of (merely) providing ‘practical guidance’ to law-appliers. While the ILC’s pragmatic impetus may excuse some of this theoretical imprecision, d’Aspremont’s taking-on-board of this preference is particularly problematic. Discussing the ILC project in a recent paper, he harks back to an understanding of sources he had held earlier – before his recent sceptical turn – of the ‘sources’ as ‘law-ascertainment’.Footnote 57 In International Law as a Belief System, he mentions ‘the establishment of two distinct facts, that is, practice and opinio juris (acceptance as law)’ which are ‘the dominant modes of legal reasoning to determine the existence and content of a rule of customary international law’Footnote 58 – determine the existence, not create. Law-creation is thus robbed of its legal character, harking back to old, yet still popular ideas of the sources of law as not themselves law.Footnote 59

This sustained privileging of the law-cognising over the law-creative function has wide theoretical implications. If the ‘state practice plus opinio juris’ formula is merely, but necessarily, the only legitimate method for determining the existence and content of CIL, is it not peculiar that this process is so rigid, formal and so much like a form of law-creation? Is it not much more likely that a whole range of (epistemic) ‘methods’, which may not have much to do with the two elements, allow us to cognise whether CIL exists and how it is shaped? Is it not much more likely (and does it not accord better with the mainstream understanding of customary law) that state practice and opinio juris are the two elements of law-creation – the two conditions which international law prescribes for the creation of norms of the type ‘customary international law’ – rather than ‘mere’ law-ascertainment or law-identification?

How likely is it that state practice and opinio juris are purely of epistemic interest, rather than factors of law-creation? On that view, state practice and opinio juris would be the microscope with which we can observe cell division, not the cell division itself. If we assume that state practice and opinio juris are mere epistemic tools, how does CIL come about, then? Do we not need customs and a belief or consent to be bound? Even on the epistemic level, would it not be much more sensible to argue that the cognition of CIL involves, as I put it in earlier writings, ‘a re-creation of its genesis’,Footnote 60 that is, an analysis of the various instances of state practice and opinio juris, precisely because these two elements are legally required to create CIL? If this were a debate about domestic legislation, nobody would be tempted to ascribe the label ‘means of law-identification’ to the approval of the bill by the Houses of Parliament or to the sanction by the head of state.

Neither the ILC nor d’Aspremont tell us what, exactly, this ‘identification’, ‘determination’ or ‘ascertainment’ is. Are they properly part of the cognitive faculties – epistemic processes of law-cognition? How can they then be rule-governed? Probably a similar shift in meaning has taken place as for what I have called ‘interpretationB’ – a process preparatory to application, to be performed by organs, guided by rules somehow inherent to the legal order, but utterly muddled by confounding it with real cognitive processes (interpretationA). In our case, we would get custom-identificationA versus custom-identificationB. Probably also, the idea of ‘rules’ of custom-identification is as misguided as the idea of rules of interpretation which can somehow determine the hermeneutic process.Footnote 61

4.2 The Problem of Source-Law (Meta-meta Law)

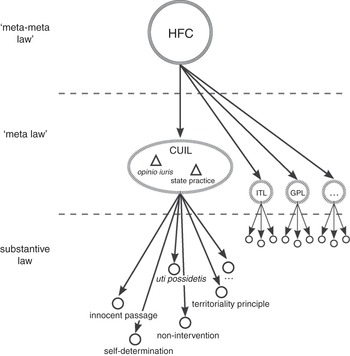

Law-identification is important, but it cannot be part of the law. I believe that the whole debate is either a conscious strategy to avoid tackling the problems of law-creation without a written constitution (as a form of avoidance behaviour) or a subconscious category mistake. Figure 1.1 illustrates the different levels which many confound, partly because it is more convenient to do so, partly because of a genuine belief in the post-ontological and anti-metaphysical mindset. As argued in Section 2.2: in order to be able to see law as counterfactual and in order to be able to speak of ‘you ought to do/abstain from doing “x”’ in any meaningful sense, law (norms) cannot be reducible to facts, whether linguistic, factual or psychological. We cannot supplant law and law-making for ascertainment, for linguistic practices and for an analysis of the way we talk about the law – as much as we need to talk about these issues as well. If we follow this reductivist path, the whole idea of rules becomes precarious. What is left of law as standard setter if all we can do is look at linguistic practices?

Figure 1.1 Levels of discussion.

On a non-reductivist reading, then, there are at least three levels of legal-scholarly discussion: (1) legal scholarship analyses (cognises) which norms are valid, particularly (1a) empowerment norms, that is ‘source law’.Footnote 62 (2) It may be possible to speak of a separate discussion about law-identification where the various proofs or evidences for the validity of various norms (particularly empowerment norms) are discussed. This is unlikely, however, because this pragmatic issue will probably be subsumed under (1) or (3). (3) Legal methodology, then, discusses the (proper) methods which legal scholarship may use/uses in order to correctly cognise the law.Footnote 63

In contrast, Figure 1.2 shows the different ‘levels’ of the law itself – the hierarchy of empowerment norms (‘sources’) and law created under it.Footnote 64 This is the object of cognition for legal scholarship as ‘structural analysis’Footnote 65 of legal orders (level (1) above). ‘The legal order is not a system of coordinate legal norms existing alongside each other, but a hierarchical ordering of various strata of legal norms,’ writes Hans Kelsen. For him, ‘a norm which has been created according to the terms of another norm derives its validity from that latter norm’,Footnote 66 ‘validity’ being the specific form of existence for norms/law. Also, however, such a derivation is necessary: ‘a norm [is] valid, if and when it was created in a certain fashion determined by another norm’,Footnote 67 because we need to keep apart the norms (Ought) as claims to determine human behaviour from ‘mere’ reality.

Figure 1.2 Levels of the law.Footnote 68

The structure of international law might approximate that given in Figure 1.2:

– The level of substantive norms contains a number of CIL norms, like uti possidetis or the right to innocent passage, but also a multitude of ‘cousins’ from other sources, such as the treaty norms like the prohibition on the threat or use of force in Article 2(4) UN Charter or the prohibition of expropriation in Article 13(1) Energy Charter Treaty 1994.

– The meta-law contains a number of ‘sources’: the empowerment norms to create substantive norms. One such (complex) norm for CIL must be part of international legal order for substantive customary law norms to be able to ‘exist’, that is: be valid. On the traditional reading, then, this empowerment norm prescribes two conditions – state practice and opinio juris – to be fulfilled in order for a customary norm to be created.

– If customary and treaty law as well as general principles are to be equals, yet if all of international law is to be one legal order, a further norm is required, since creation according to the same empowerment norm constitutes unity among a multitude of norms.Footnote 69 This could be what Kelsen calls ‘historically first constitution’ (historisch erste Verfassung):Footnote 70 the hierarchically highest positive norm of a positive normative order. It is what I have called ‘meta-meta law’,Footnote 71 the legal determinant for which sources the international legal order contains.

The distinction between these levels is crucial, as our arguments about the content of the empowerment norm for CIL can only be grounded on this level. In other words, if author A were to argue that state practice is not a required element for the creation of CIL and that this is the case because many morally valuable (proposed) norms would not exist otherwise,Footnote 72 A must fail. A could succeed only if they could prove that the meta-law for custom-creation is shaped that way. A’s arguments regarding the meta-law, in turn, depend on the shape of meta-meta law: A’s claim that customary international law-making does not require state practice is true if the meta-law is shaped that way; the meta-law is shaped that way if it has been created according to the meta-meta law.

On a truly legal-theoretical perspective, the solution must lie within the law, as law regulates its own creation. The coming-about of CIL is and has to be based on law. Hence, we must find that meta-law, the law on customary international law-making. Yet the tragedy which I have frequently decried is that while we must proceed in this manner in order to generate legal-scholarly knowledge, we cannot do so. Those ‘empowered to will the highest echelons of international law … are unlikely to ever have’Footnote 73 created meta-meta law. There are also limits to what we can say about international law at this high level. Our epistemological horizon is too limited to answer this question with more than a presumption. As long as we are presupposing, we could presuppose any ‘method’ to create customary law, even an absurd one. Whatever the case, our knowledge of the content of meta law suffers, because there is little we can do to improve our knowledge of the historically first constitution.

What will never do is to say that this justifies basing our arguments (eg on whether state practice is required) on considerations of pragmatic expediency, political legitimacy or moral necessity: even if there were no meta-meta law (and CIL were to be its own legal order with the Grundnorm: consuetudines sunt servanda), arguments of this type would still be based on a category mistake. What will also not do is the ILC’s ‘optimistic’ approach: the attempt to trivialise and minimise the problems of CIL by maximising the leverage of the most widely accepted positions. This is combined with the acceptance of the factual influence of the orthodox position, foremost the ICJ’s jurisprudence constante. When asked what the ‘rules for identifying the sources of the law’ are, Wood’s answer is this: ‘These can be found … by examining in particular how States and courts set about the task of identifying the law.’Footnote 74 While Wood uses the word ‘identifying’, rather than ‘creating’, identification supplants creation in the ILC project (Sections 2.1 and 4.1).

4.3 Approximately Plausible Empowerment Norm

As mentioned above, this is the point where my analysis usually ends: little more can be said, from a legal-theoretical point of view. We cannot know more; those who purport to do so base their arguments on ineligible grounds. In this, we must face a particular problem for the international legal order which permeates all normative orders: how to proceed when the law is ‘sparse’? In other words, what is the ‘default’ position when there is little in the way of (proven or provable) law? This question may look a lot like a burden of proof in the strict sense (ie which of the parties to a judicial procedure has the burden for specific arguments), but it is not. The default position question may or may not arise in judicial proceedings, but it is found on a different level than the standards of proof required by the procedural law for a particular tribunal. It is connected, in a contingent way, to the scholarly ‘burden of proof’, a burden of proof in a very wide sense: what does scholarship have to do in order for its arguments to satisfy the requirement of generating knowledge about the law? For example, scholarship usually does not have to prove a contention that a proposed norm is not valid (although there may be situations where it does); if a scholar claims, however, that ‘x’ is a norm of, say, CIL, this needs to be proven to be accepted as a ‘true’ legal-scholarly statement, rather than wishful thinking.

The default position question may also remind us of the ‘residual negative principle’ and the (in)famous dictum in Lotus that ‘[r]estrictions upon the independence of States cannot … be presumed’.Footnote 75 The voluntarist straw-man which has dominated much of international legal scholarly discussion of this passage is, I believe, mistakenly applied to it and another reading of the dictum is better-aligned with legal theory:Footnote 76 ‘“Restrictions” are only applicable if they are positive law of the normative system “international law”. If there is no law, there is no law.’Footnote 77 Under that reading, the non-validity of norms is the default; it thus provides a partial answer to the question.

If we cannot prove the content of an empowerment norm for CIL, yet arguendo proceed from the presumption that ‘customary international law’ exists and that there is such an empowerment norm, what would be the ‘default’ position? In a 1970 book, Herbert Günther mentions that he would proceed on the basis of ‘the assumption that custom … has the power to create law’:Footnote 78

If the norm empowering customary international law as source is thus called a ‘hypothesis’ or ‘postulate’, it is done only in the sense that this is conditional upon our being correct in that certain acts can create an Ought. The presumptive validity of particular norms of customary international law, derived as it is from the constituting norm [the source], is thus hypothetical as well: it is only possible to cognise a particular norm of customary international law as valid if the hierarchically higher norm on law-creation is seen as law and as norm.Footnote 79

This solution sounds quite Kelsenian. There would be a Grundnorm with the content: consuetudines sunt servandaFootnote 80 for a small legal order, comprising CIL (and potential subordinate sources) only, but not international law as a whole. This is also very close to my proposal ‘to incorporate all conditions for the creation of … customary law … into the postulated Grundnorm of … customary international law’. However, as I argued then, this cannot work, because the Grundnorm ‘cannot create what is not already positive. It only gives validity as existence as Ought’.Footnote 81

I propose a much weaker heuristic tool, which I will call the Approximately Plausible Empowerment Norm (AppPEN). If we assume (a) that international law contains a positive empowerment norm for ‘customary international law’ and if we assume (b) that the ‘formal source’ thereby constituted includes a creation mode of the customary type, then certain arguments/forms of regulation are made more plausible and certain others are less plausible. This is informed legal-theoretical speculation that the international legal order is shaped that way, not abstract deductive proof. However, there are degrees of plausibility, because the possible structure of normative orders and the idea of law as norms (Ought) is not completely arbitrary and because we can in some cases see constructs not based on logical fallacies as more plausible than those who celebrate inconsistency. Yet this idea is not orthodox majority following: constructs (such as the two-element theory) are not part of AppPEN because they are widely accepted by peers, but because they are more plausible than single-element theories. AppPEN is thus much weaker than ‘ordinary’ legal-scholarly proof of the validity (vel non) of a specific norm, but it may be the best we can hope for, given our poor epistemic position vis-à-vis the highest echelons of the international legal order.

A few examples for this positive and negative plausibility might show how AppPEN would operate:

– It is more likely that CIL is based on customs – repetition of behaviour – than not. It is trivially true that an empowerment norm (‘formal source’) could prescribe norm-creation without requiring regular behaviour as basis, for example domestic legislation. However, whether or not we now propose renaming it,Footnote 82 it is more likely that a source called ‘customary’ law is based on customs than not, particularly since the more than 1,500 years of debate have been reasonably consistent on this point.

– It is more likely that CIL is its own legal order than part of a complex hierarchically ordered international legal system. If we cannot prove meta-meta norms incorporating CIL, international treaty law, general principles etc. as part of one legal order, it is more likely that no such norm is valid. Hence, ‘international law’ may refer to a family of legal orders, rather than to one.Footnote 83

– It is more likely that there is one source ‘customary international law’ than a whole range of sources. It is possible that a number of empowerment norms is valid which allow for the creation of a whole range of non-treaty international law. Alfred Verdross proposes a variation on this scheme in a 1969 article: ‘It is impossible to found all unwritten norms of international law on the same basis of validity’; ‘yet, it is likely that there is some truth in all theories’Footnote 84 of how CIL is created. Hence, he argues to accept all those procedures which usually succeed in creating CIL. The theoretical basis for this argument is flawed – we cannot know that CIL has been created unless we know the law on creation, which is exactly what we set out to find. Yet it is also unlikely in terms of Occam’s razor: the creation of one empowerment norm is incredibly difficult, see the endless debates about customary international law-making; it is less likely that a whole plethora of such norms is valid, rather than one (or even none), particularly given that we have traditionally discussed only one.

5 Conclusion

I have only given a first impression of what AppPEN is and how it could be used. In particular, I foresee two types of use. The first is pragmatic, similar to the idea behind the ILC project: it allows those who have little time to study the various theories of and approaches to CIL and international legal theory – like judges of domestic and international courts and tribunals – to circumnavigate some of the problems by weeding out implausible and selecting plausible theories. The second, however, is legal-scholarly: doctrinal (international) legal scholarship cannot always question all its foundations and will have to make a number of assumptions. AppPEN helps to select those which are more plausible. Neither practitioners nor doctrinal scholars are, however, best served by the orthodox modus operandi visible in the ILC report. If, for example, a widely held argument is based on a contradictio in adiecto, the fact of the acceptance by peers cannot be better than an approach which consciously avoids solutions which are logically flawed or which are based on an incoherent legal theoretical stance. Legal theory’s goal is not to provide a balanced theory, that is, a theory likely to be most widely accepted by international lawyers, because this implies that truth is to be found in compromise and majorities. Rather, it is meant to be consistent and consistently legal, a theory which takes the positive law seriously, yet shows where the law ends, where arguments are self-contradictory and where pragmatism becomes a fetish.

If we do not wish to operate on such a provisional basis, however, the most consistent course of action is to learn to live with much less CIL than we are used to imagining. At the very least we must acknowledge that customary law is a primitive mode of law-creation: we can do much less than we commonly assume. Customary law cannot be international law’s ‘saviour’ or its ‘future’ – the Zeitgeist will never walk where it can run.

1 Introduction

Customary international law (CIL), as it is commonly construed in international legal thought and practice, is grounded in a particular social reality. In fact, the two constitutive elements of CIL, namely practice and opinio juris, correspond to two sides of the social reality which CIL is supposed to be grounded in. This is no new state of affairs. Even in the nineteenth century where CIL was thought to be the product of tacit consent, customary international law was construed as the product of social reality.Footnote 1 This social grounding of CIL is certainly neither spectacular nor unheard of. That CIL is grounded in a particular social reality bespeaks a construction that has become rather mundane since the Enlightenment,Footnote 2 and according to which norms are no longer supposed to be received by their contemplatingFootnote 3 addressees but are collectively producedFootnote 4 by them as members of a self-conscious social community.Footnote 5 Such an understanding of the making of CIL as originating in a process of self-production, where the authors and the addressees of the customary norm are conflated,Footnote 6 is a manifestation of modern thinking.

Although simple in principle, the grounding of a norm in a social reality is a construction that commonly calls for a number of discursive performances for this grounding to be upheld in the discourse.Footnote 7 The present chapter zeroes in on one of these discursive performances that is required for CIL to be grounded in social reality, namely the postulation of a moment in the past where the social reality actually engendered the norm. In fact, the grounding of CIL in a social reality captured through practice and opinio juris can only be upheld if there was a moment in the past where the practice and opinio juris of states – and possibly of other actorsFootnote 8 – have coalesced in a way that generates customary international law. In other words, for CIL to be grounded in social reality, there must have been a moment in the past where customary international law was actually made.

This chapter argues that, in international legal practice and literature, the actual moment where social reality has engendered a customary norm is never established or traced, but is always presupposed.Footnote 9 According to the argument developed here, the moment CIL is made is located neither in time nor in space. Customary international law is always presupposed to have been made through actors’ behaviours at some given point in the past and in a given place. Yet, neither the moment nor the place of such behaviours can be found or traced. In other words, there is never any concrete moment where all practices and opinio juris coalesce into the formation of a rule and which could ever be ‘discovered’. This means that the behaviours actually generating the customary rule at stake are out of time and out of space. Because the custom-making moment is out of time and out of space, it cannot be located, found, or traced, and it must, as a result, be presumed. This is why current debates on CIL in both practice and literature always unfold as if all actors’ behaviours and beliefs had at some point coalesced into a fusional process leading to the creation of customary international law. However no trace of that fusional moment can ever be found, condemning this original fusion of all behaviours and beliefs to be presumed.Footnote 10 This presumption of a moment in the past where the social reality creates the norm is called here the presumption of a custom-making moment. Most debates on CIL in practice and in the literature are built on such a presumption of a custom-making moment. As was said, this presumption of a custom-making moment is necessary for CIL to present itself as being grounded in a certain social reality.

This chapter is structured as follows. It first sketches out some of the main manifestations of this presumption of a custom-making moment (1). It then sheds light on some of the discursive consequences of presuming a custom-making moment, including those consequences for the interpretation of CIL (2). The chapter ends with a few observations on what the presumption of a custom-making moment entails for foundational debates about CIL as a whole (3).

Before elucidating the manifestations of the presumption of a custom-making moment and its consequences, a preliminary observation is warranted in light of the presumptive character of the custom-making moment. It could be claimed that the presumption of a custom-making moment is, like opinio juris,Footnote 11 yet another fiction around which CIL is articulated. In that sense, the custom-making moment would be a fiction about the origin of CIL. It is submitted here that claiming that the custom-making moment is a fiction says basically nothing about what such a presumption stands for and actually does. Indeed, it could be said that international law’s representations of both the reality and the past are always fictitious constructions.Footnote 12 What is more, fictions have always been a common mode of representing the real.Footnote 13 That CIL rests on a fictitious representation of the moment of its making can thus not be demoted to just another fiction of international legal reasoning. It is a powerful discursive performance without which CIL could not do all what it does.

2 The Custom-Making Moment in the International Legal Discourse

The following paragraphs mention a few of the manifestations of the presumption of a custom-making moment in international legal thought and practice. It is, for instance, noteworthy that practice and scholarship continuously set aside the question of the duration of practice, as the determination of a minimum threshold would bring back the question of the custom-making moment.Footnote 14 The recurrence of the metaphoric shorthand of ‘crystallisation’ to describe the formation of customary law in the literature similarly epitomizes the continuous avoidance of finding a custom-making moment and the presumption of the latter.Footnote 15 In the same vein, it is striking that courts always locate the practice and opinio juris they find in the present,Footnote 16 thereby constantly avoiding the tracing of a custom-making moment.

The presumption of a custom-making moment has occasionally been touched on in the literature. For instance, the famous discussion on the chronological paradox of CIL is a question that, although focused only on opinio juris, is all about the abovementioned presumption of a custom-making moment.Footnote 17 Yet, those debates on the chronological paradox of CIL never explicitly acknowledge the presumption of a custom-making moment. Reference could also be made to scholarly discussions about the relations between a customary international legal rule with a corresponding existing treaty provision.Footnote 18 In this situation, the treaty seems to provide some indication of the time and place of the making of CIL.Footnote 19 And yet, here too, despite the treaty providing some vague direction in this regard, there is no effort to identify a custom-making moment, the latter remaining presumed.

It is remarkable that the International Law Commission (ILC), in its work on the identification of CIL, consciously decided not to look into the custom-making moment either. Indeed, as it stated in the commentaries to its 2018 conclusions:

Dealing as they do with the identification of rules of customary international law, the draft conclusions do not address, directly, the processes by which customary international law develops over time. Yet in practice identification cannot always be considered in isolation from formation; the identification of the existence and content of a rule of customary international law may well involve consideration of the processes by which it has developed. The draft conclusions thus inevitably refer in places to the formation of rules of customary international law. They do not, however, deal systematically with how such rules emerge, change, or terminate.Footnote 20

Interestingly, it is this very choice to exclude the question of the formation of customary law from the scope of its work that entailed a change in the way in which the ILC described its own work.Footnote 21 It is submitted here that such a choice is not informed by the material impossibility to trace the formation of CIL or the irrelevance of the question for custom-identification, but by the very fact that this presumption is at the heart of the contemporary understanding of CIL. Being presumed, it does not even need to be traced. In the discourse on CIL, the question of establishing or tracing the custom-making moment simply never arises.

3 The Custom-Making Moment and its Doings

It is argued here that the presumption of a custom-making moment is not just a move of convenience to evade difficult methodological and evidentiary obstacles pertaining to the identification of CIL. Such a construction is being perpetuated for its many discursive virtues. Indeed, as was indicated above, CIL could not be upheld as being grounded in social reality if it could not be presumed as being made at a certain moment in the past. If it were not presumed to be made at a given moment in the past where opinio juris and practice coalesce and generate CIL, it would not be possible to hold that CIL originates in some form of social reality.

In enabling the grounding of CIL in social reality, the presumption of a custom-making moment simultaneously allows some other discursive moves which are worthy of mention here. In particular, attention must be turned to the way in which the presumption of a custom-making moment enables a two-dimensional temporality in the discourse on CIL. In fact, it organizes the life of CIL around two distinct moments, namely: (i) the (presumed) moment of making of CIL in the past; and (ii) the application of CIL in the present.Footnote 22 If CIL has a past, albeit presumed, it can have a present distinct from that past. The postulation of a custom-making moment in the past thus allows the postulation of other ‘moments’. In particular, this two-dimensional temporality enables the idea that CIL is a product made in the past and subjected to interpretation in the present. Because one presupposes a custom-making moment in the past, one can think of CIL as a tangible artefact in the present which can therefore be subject to an autonomous and neatly organised interpretive process.Footnote 23 This is why those scholars that argue that the interpretation of the content of CIL can be distinguished from the interpretation of its legal existenceFootnote 24 extensively and systematically build on this two-dimensional temporality.Footnote 25 In that sense, the current scholarly attempts to distinguish the interpretation of the making of the CIL rule from the interpretation of its content can be seen as being predicated on this presumption of a custom-making moment.

There is another important consequence of the presumption of a custom-making moment that ought to be mentioned here. That is, the anonymity and impunity in argumentation about CIL that accompany the presumed custom-making moment and its abovementioned two-dimensional temporality. Indeed, since the custom-making moment is outside time and out of space, and simply presumed, those generating the custom-making behaviours cannot be known. The only possible pedigree of customary international law comes to be reduced to ‘all states at some point in the past’. Being presumed, the custom-making process is actually anonymised. This anonymity is explicitly confirmed by the ILC:

The necessary number and distribution of States taking part in the relevant practice (like the number of instances of practice) cannot be identified in the abstract. It is clear, however, that universal participation is not required: it is not necessary to show that all States have participated in the practice in question. The participating States should include those that had an opportunity or possibility of applying the alleged rule.Footnote 26

The above statement shows that it is not necessary for the sake of custom-ascertainment to even seek to identify who did (or said) what. The ILC is thus saying that the custom-making moment, because it is presumed, ought not to be traced, named and individualised. Being presumed, the making of CIL can stay anonymous.

The anonymity that accompanies the presumption of the custom-making moment is not benign. In fact, as a result of this anonymity, no one can ever be made responsible for the rule of CIL concerned and what is claimed under its name. In other words, as any customary rule enjoys a life of its own out of time and out of space, what is said under the discourse on CIL cannot be blamed for both the good and the suffering caused in the name of CIL. All those invoking CIL can accordingly present themselves as candid followers and observers who just walk behind CIL, be it for the good or the suffering made in the name of CIL.Footnote 27

4 Concluding Remarks: The End of Foundationalism?

Customary international law epitomizes the idea of grounding. Indeed, by virtue of CIL, the rules to which a customary status is recognised are supposedly grounded in a past social reality. And yet, as has been argued in this chapter, such grounding can never be traced but can solely be presupposed.

It is submitted at this concluding stage that the question of whether this presumptive grounding of CIL is a satisfactory state of the discourse is irrelevant. It is particularly argued here that foundational debates about whether a customary international law rests on valid or invalid, consistent or inconsistent, legal or illegal, grounded or arbitrary, true or untrue, factual or imaginative foundations are bound to be sterile since the foundations of CIL are condemned to be presumptive.Footnote 28 As was shown by this chapter, venturing into foundational debates about the validity, truth, legality, consistency and factuality of the foundations of CIL is to condemn oneself to an inevitable defeat.

Yet, it must be emphasised that the limitations of foundational debates about CIL do not entail that one should verse into relativism, nihilism or even discourse vandalism. Although twenty-first-century post-truth delinquents feel they have made a groundbreaking discovery about the origin-less-ness of discourses, it has long been shown that modern discourses cannot meet their own standards in terms of origins and grounding.Footnote 29 The same holds for international law, and even more so for CIL.Footnote 30 That does not mean, however, that CIL, or all the discourses that cannot meet their own standards of origin and grounding, ought to be derided, disregarded or vandalised.Footnote 31 On the contrary, a discourse should be appreciated for how it does what it does, and especially for its origin-less and untraced performances. In that sense, it is once one is liberated from foundational debates about CIL that one can measure and appreciate both the discursive splendour and the efficacy of the latter.

1 Introduction

This chapter explores the misinterpretation of customary international law (CIL) and its practical and normative consequences. I focus on three main questions: (1) what is misinterpretation? (2) how and why do different misinterpretations take place? and (3) what are the potential consequences of misinterpretation of CIL? These all converge in the underlying question of whether there are detectable objective standards for the determination of misinterpretation or whether such observation is a subjective one – anchored on a disagreement on the values which lie at the core of international law.

In exploring these questions, I combine doctrinal study with empirical examples. Additionally, the different potential consequences of misinterpretation call for a normative evaluation: whether misinterpretation renders a norm invalid or illustrates lex ferenda? Could misinterpretation create an authoritative verdict of the status of law, even against its flawed premise – ‘a corrupt pedigree’, a term coined by Fernando Teson?Footnote 1 And why does pedigree matter for CIL – is there something beyond institutional formality conferring authority and legitimacy?

By its nature, CIL is constantly evolving – the customary process is continuous. While in its purest form interpretation of CIL may consist of an analysis of an already ascertained rule (and its elements), interpretation of CIL in most cases inevitably includes an element of construction at that particular point in time – it is difficult to distinguish between the formation, identification and interpretation of CIL.Footnote 2 As Anthony D’Amato has noted in relation to CIL: ‘there is an interrelation between law-formation and law interpretation’.Footnote 3

According to traditional methodology, CIL emerges spontaneously ‘like a path in a forest’.Footnote 4 It has been suggested, somewhat convincingly, that the identification and interpretation of CIL have taken a strategic turn, potentially arising from the proliferation of international interactions and norm-interpreters and -entrepreneurs.Footnote 5 The theories of ‘modern CIL’Footnote 6 have attempted to explain and justify the broadened methodology, which utilises CIL to advance political, ethical, economic and other aims. Some of such attempts may in fact encourage and expand potential misinterpretations of CIL, with reliance and application of elements far removed from the common understanding of state practice and opinio juris. The effect is not relevant only in the methodology but also in the outcomes: with the utilisation of different interpretative methodologies by different courts and other norm-interpreters,Footnote 7 the resulting identification of a rule of CIL and/or its subsequent interpretation could be highly inaccurate, due to either a genuine mistake in the interpretive methodology or an aspiration to apply a progressive norm disguised as customary rule for moral, ethical, policy, or other extra-legal reasons.

Following the ‘CIL as a path’ metaphor, the interpreter of a norm may misidentify, say, a dried-up stream as a path, designate a minor trail as a fully-fledged path, find a path where there is none, or call a man-made walkway a path. These present examples of misinterpretations without delving into their underlying motives. It is, however, useful to analyse reasons behind a misinterpretation as they may have a direct bearing on the consequences flowing from it, how it is received and responded to by the international community, and for the determination of whether it is representative of ‘a corrupt pedigree’ or a matter of sluggish methodology.

While Articles 31 to 33 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) serve as the starting point for addressing interpretation in international law – and these rules have crystallised as part of CIL in their own rightFootnote 8 – they provide little guidance on how to interpret CIL rules. Just as well, courts have adopted and adapted their own approaches and methodologies on how to go on about interpreting CIL, and not always consistently even within the same institution. In this chapter I intentionally avoid delving into the discussion of what constitutes interpretation: this is accomplished by other authors in this volume.Footnote 9 One may criticise my approach for cutting corners or reversing the analysis while pursuing exactly the same result: exploring what interpretation is not. I accept that the critique may be warranted. The purpose here is, however, not to provide an ample understanding of the misinterpretation of CIL but to initiate conversation on how interpretation may go awry and what it may do to the validity and legitimacy of CIL.

Capturing the definition and examples of misinterpretation is like chasing a moving target – as with interpretation, the elements may be in flux, the circumstances and narratives changing, and the line between genuine and fake CIL – and correct interpretation and misinterpretation – often fluid. With CIL identification (and possibly subsequent interpretation), one can usually find evidence to support what one is looking for – but so can the opposite party. Transplanting a correct interpretation reached at a given point in time into a later case may in fact provide the very premise for misinterpretation even when the methodology of the initial interpretation has been accurate per se: the act of interpreting CIL requires the interpreter to analyse the practice and opinio juris at a specific point in time. By definition, CIL can develop continually and therefore the interpreter needs to look beyond the matter or dispute at hand to get a broader vision of the applicable evidence of the elements of CIL. This argument runs somewhat parallel to Article 30 of the VCLT on the application of successive treaties relating to the same subject matter and to its Article 31 (3) (a) and (b) on subsequent agreement and practice in the interpretation of a treaty: the commentaries call for consideration of what is appropriate in particular circumstances and for caution in resorting to effective interpretation, noting that ‘even when a possible occasion for [principles and maxims’] application may appear to exist, their application is not automatic but depends on the conviction of the interpreter that it is appropriate in the particular circumstances of the case’,Footnote 10 and that to resort to extensive or liberal interpretation ‘might encourage attempts to extend the meaning of treaties illegitimately on the basis of the so-called principle of “effective interpretation”’.Footnote 11 The commentaries also touch upon consequences of such extensive interpretation, with a reference to the 1950 Interpretation of Peace Treaties Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), where the court emphasised that to adopt an interpretation which ran counter to the clear meaning of the terms would not be to interpret but to revise the treaty.Footnote 12 In a similar manner, to interpret CIL ‘effectively’ or in a way that runs counter to established practice and opinio juris, could either constitute a revision of the rule of CIL (if it is shown that new practice and opinio have emerged) or, as is the focus here, result in misinterpretation (if practice and opinio do not sufficiently support the new interpretation). As noted by the arbitrator in the Island of Palmas case: ‘The same principle which subjects the act creative of a right to the law in force at the time the right arises, demands that the existence of the right, in other words its continued manifestation, shall follow the conditions required by the evolution of law.’Footnote 13