Directly funded (DF) home care provides public funding to individuals to arrange their own home support services, through a cash allowance or allocated hours for services. DF programs may also be referred to as self-managed, self-directed, family-managed, direct payment, or cash-for-care. Research shows that working-age self-managers are more satisfied and report better overall well-being and improved self-esteem with DF home care than with regular home care (Carlson, Foster, Dale, & Brown, Reference Carlson, Foster, Dale and Brown2007; Ottmann, Allen, & Feldman, Reference Ottmann, Allen and Feldman2009). Over the past two decades, DF home care has been increasingly used by older adults and their families, and this population group may have differing expectations of or needs for home care services linked to life stage, acquiring disabilityFootnote 1 later in life, and/or living with cognitive impairments (Moran et al., Reference Moran, Glendinning, Wilberforce, Stevens, Netten and Jones2013; Woolham, Daly, Sparks, Ritters, & Steils, Reference Woolham, Daly, Sparks, Ritters and Steils2017).

This article presents findings from a qualitative study of the Self and Family Managed Care (SFMC) program, a DF program in Manitoba, Canada. Drawing on in-depth semi-structured interviews with older adult program users and caregivers (n = 24), our research asks, what are the experiences of family managers arranging services for an older adult through the SFMC home care program in Manitoba? Our literature review considers research on the needs of family caregivers, and the limited research exploring the extension of DF home care to older people and their families. Our approach is underpinned by the principle that family managers arranging services for an older person’s needs will have experiences that differ from self-managers arranging for their own needs. We identify three themes in the interview data: (1) DF home care enhances choice and flexibility for older people and their caregivers, (2) choice and flexibility reduce caregiver strain, and (3) agency services reduce administrative burden. Based on the findings, we recommend that increased administrative support would help family managers and encourage accessibility among families supporting older home care users while maintaining the choice and flexibility traditionally offered by DF.

Context

There are 20 DF home care programs in Canada serving a range of clientele (Kelly, Dansereau et al., Reference Kelly, Dansereau, Balkaran, Tingey, Aubrecht and Hande2020). Ten of these programs, one in each province, serve adult home care populations who require assistance with the activities of daily living, and older adults with cognitive disabilities (including dementia). All DF programs in Canada use a similar policy mechanism of a cash transfer, reimbursement, or assigned budget that allows individuals and families to organize and arrange their own support services. Most of the programs in Canada allow a family member or legal representative to help with the administration.

This article focuses on the Manitoba DF program, which was piloted in 1991 as an alternative to publicly delivered home care for younger adults with physical disabilities (Spalding, Watkins, & Williams, Reference Spalding, Watkins and Williams2006). The successful pilot project expanded to allow family members to direct care services on behalf of a home care client of any age or diagnosis, resulting in the SFMC program. Any provincial resident living in the community, including retirement residences and 55 plus communities, is eligible for public home care services based on clinical assessment of need. Anyone eligible for home care may opt into the SFMC program if they have the desire and capacity to direct their own services (hereafter referred to as a self-manager) or have an unpaid family member willing to take on the duties of directing services on their behalf (hereafter referred to as a family manager). The care plan, as determined by a professional needs assessment, is transformed into a cash allowance based on the public cost of providing those services. The self-managed model generally consists of self-reliant younger adults, whereas family management tends to represent older adults and their extended care networks. Family members may be hired as workers, but only on a case-by-case basis.

The majority of home care services in Manitoba are arranged by regional health authorities regulating the tasks that workers are allowed to do and how long those tasks should take. Personal care is provided by people trained as health care aides, and lesser-paid support workers provide housekeeping services. Provincially employed care workers are not normally permitted to provide services outside the home (such as shopping, or escorting clients to appointments). In contrast, care managers in SFMC may purchase services from private care companies (non-profit and for-profit) with presumably fewer constraints. SFMC also permits managers to hire their workers directly, and assign them to virtually any task that the care manager deems necessary (Kelly, Hande et al., Reference Kelly, Hande, Dansereau, Aubrecht, Martin-Matthews and Williams2020). In the direct-hire model, a single worker may be assigned tasks without differentiating based on certification level, and with the additional flexibility of allowing their job description to include going on outings or chatting over tea.

The Manitoba DF program served 2.6 per cent of the province’s home care users (980 clients) at the time of data collection in 2018 (Kelly, Dansereau, et al., Reference Kelly, Dansereau, Balkaran, Tingey, Aubrecht and Hande2020). Approximately 40 per cent of care managers used program funds to purchase home care services from private companies, while 60 per cent acted as direct employers, which involved hiring, training, scheduling, and performing payroll for workers recruited from local communities and social networks.

Theoretical Influences

Disabled people and the Independent Living movement shaped and helped establish DF home care as a vehicle for allowing personal control over everyday life and engagement in the community and broader society (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007; Batavia, DeJong, & McKnew, Reference Batavia, DeJong and McKnew1991; Tate, Reference Tate1984; Yoshida, Willi, Parker, & Locker, Reference Yoshida, Willi, Parker and Locker2000). The Independent Living movement is a social movement, a network of non-profit organizations, a philosophical orientation towards disability, a theoretical framework, and an analytical paradigm (DeJong, Reference DeJong1979, Reference DeJong, Crewe and Zola1983; Hutchison et al., Reference Hutchison, Pedlar, Lord, Dunn, McGeown and Taylor1997; Longmore, Reference Longmore and Longmore2003). This philosophical perspective defines independence in terms of making decisions (rather than physically doing things for oneself), positions the DF home care user as the expert over their bodies and needs, and demands that disabled people have control over the services directed at them as a consumer or user of services rather than as a patient or client (Morris, Reference Morris1993). DF funding can thus be situated within an ethos of decision making and human rights, and a theoretical orientation to care that is aligned with an individual’s wishes and that supports community engagement.

Exploring how DF plays out for older people addresses a knowledge gap and a divide that exists within the research and practise related to both aging and disability. Disability activism and research on the experiences of people with disabilities have tended to overlook issues related to age and aging (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2014; Raymond & Lacroix, Reference Raymond and Lacroix2016). Grenier, Griffin, and McGrath (Reference Grenier, Griffin, McGrath, Aubrecht, Kelly and Rice2020), for example, critique how the emphasis on the chronological life course perspective has positioned disability “outside the standard view of the life course” and at the same time conflated disability and aging in later life (p. 22). Many people acquire disability in older life, and disabled bodies age, but people also overlap or fall between these experiences, and age and disability are merely two of the many intersections a person may identify with (Aubrecht, Kelly, & Rice, Reference Aubrecht, Kelly and Rice2020; Calasanti & King, Reference Calasanti, King, Twigg and Martin2015; Green, Evans, & Subramanian, Reference Green, Evans and Subramanian2017).

Literature Review

Our study is situated within two key bodies of literature. The first is research on family caregivers and their needs. The second is research on the implications of extending DF home care beyond young adults with physical disabilities to serve a broader population base that includes older people.

The Potential for DF Home Care to Address Caregiver Needs

DF home care may help address the documented shortcomings of other forms of home care programs. Home care is perceived by caregivers as a form of respite, not only helping the client but also relieving some caregiver stress (Rose, Noelker, & Kagan, Reference Rose, Noelker and Kagan2015). Caregivers commonly criticize home care services as being overly restrictive or difficult to access, with inflexible services and hours, and characterized by poor communication and unsatisfactory worker–client relationships (Kokorelias, Gignac, Naglie, & Cameron, Reference Kokorelias, Gignac, Naglie and Cameron2019; Ormel et al., Reference Ormel, Law, Abbott, Yaffe, Saint-Cyr and Kuluski2017). Further, social support services, such as help with housekeeping or cooking, are often identified as being important to community living yet non-medical services tend to be overlooked or neglected in many home care programs (Adelman, Tmanova, Delgado, Dion, & Lachs, Reference Adelman, Tmanova, Delgado, Dion and Lachs2014; Kröger, Puthenparambil, & Van Aerschot, Reference Kröger, Puthenparambil and Van Aerschot2019).

DF home care increases choice over services, which may address a number of common caregiver concerns. DF home care workers may be assigned tasks that otherwise tend to fall to informal caregivers, such as helping with shopping or providing transportation (Kelly, Hande, et al., Reference Kelly, Hande, Dansereau, Aubrecht, Martin-Matthews and Williams2020). Families can organize services that are delivered when needed and when convenient, promoting an overall sense of service satisfaction (Cranford, Reference Cranford2020). DF home care is commonly praised for providing care continuity and fostering trusting long-term care relationships (Moran et al., Reference Moran, Glendinning, Wilberforce, Stevens, Netten and Jones2013; Ottmann et al., Reference Ottmann, Allen and Feldman2009; Prgomet et al., Reference Prgomet, Douglas, Tariq, Georgiou, Armour and Westbrook2017). In general, DF programs allow for more choice than most of the existing restrictive support options (Laragy & Vasiliadis, Reference Laragy and Vasiliadis2020).

A scoping review on research about caregivers published between 2000 and 2016 found that our knowledge is uneven; for example, much is known about younger working caregivers but less is known about older caregivers or about caring for people with complex needs (Larkin, Henwood, & Milne, Reference Larkin, Henwood and Milne2019). The authors also state that the existing knowledge base places too much emphasis on cross-sectional studies using standardised measures, and that “this approach fails to capture the multidimensionality of the caring role, and the lived experience of the carer” (p. 55). We consider the possibility that cross-sectional methods are limited in understanding caregiver experience through our qualitative study of the SFMC program.

Policy Studies Related to Expanding DF Home Care to Serve Older People and their Families

The key benefits of self-management include a sense of freedom, control, normalcy, self-determination, citizenship, and empowerment, as well as improved self-esteem (Birdwell & Fonosch, Reference Birdwell and Fonosch1980; Lord, Zupko, & Hutchison, Reference Lord, Zupko and Hutchison2000; Prince, Reference Prince2001; Ratzka, Reference Ratzka1986). Research on the outcomes associated with DF home care among older adults tends to ask whether the benefits reported by working-age self-managers are sustained under family management and among older populations with different life circumstances and care needs (see, for example Brooks, Mitchell, & Glendinning, Reference Brooks, Mitchell and Glendinning2017; Carbone & Allin, Reference Carbone and Allin2020; Roit & Bihan, Reference Roit and Bihan2019; Woolham & Benton, Reference Woolham and Benton2013).

In contexts where policy shifts have expanded DF home care to target older populations in addition to younger disabled people, the take-up among older adults and their families has been uneven (Laragy & Vasiliadis, Reference Laragy and Vasiliadis2020). This uneven uptake is associated with barriers across a variety of domains, including lack of access to information, frustration with fragmentation and bureaucracy, and lack of capacity or interest in managing the financial aspects of DF home care (Kinnaird, Reference Kinnaird2010; McGuigan et al., Reference McGuigan, McDermott, Magowan, McCorkell, Witherow and Coates2016; Ottmann et al., Reference Ottmann, Allen and Feldman2009; Rabiee, Baxter, & Glendinning, Reference Rabiee, Baxter and Glendinning2016).

A study by Askheim, Andersen, Guldvik, and Johansen (Reference Askheim, Andersen, Guldvik and Johansen2013) specifically assessed changes in overall outcomes among DF home care users that occurred in the national Norwegian DF program when regulation began to allow for family management. The study found that family management broadened the client base to include more older adults, but also reduced the average allocation of service hours, with family-managed users receiving significantly fewer hours. The authors also expressed concerns about the degree to which “user control” was implemented by family members/guardians on behalf of others. Over a series of studies, Woolham and colleagues explored the outcomes of offering direct payments and personal budgets to older adults and families in England (Ismail et al., Reference Ismail, Hussein, Stevens, Woolham, Manthorpe and Aspinal2016; Woolham et al., Reference Woolham, Daly, Sparks, Ritters and Steils2017; Woolham & Benton, Reference Woolham and Benton2013; Woolham, Daly, Steils, & Ritters, Reference Woolham, Daly, Steils and Ritters2015; Woolham, Norrie, Samsi, & Manthorpe, Reference Woolham, Norrie, Samsi and Manthorpe2019). Their overall research program indicates that the implicit aspirations for transformation, empowerment, and control common among younger DF users appeared to be incongruent with the goals of older people in later life, and that current research evidence “tends to suggest that older people achieve less satisfactory outcomes from personal budgets than younger people” (Woolham et al., Reference Woolham, Daly, Sparks, Ritters and Steils2017, p. 145). Existing scholarship in this area is very limited, demonstrating the need for in-depth, qualitative research that documents the experiences of family managers and older people using a DF home care model.

Methods

As part of a national study on all DF programs, we performed an in-depth study of the Manitoba DF program (SFMC), including a worker survey and semi-structured qualitative interviews with 23 workers and 24 program users. The findings from the national data and the Manitoba worker survey and worker interviews are reported elsewhere (Kelly, Dansereau, et al., Reference Kelly, Dansereau, Balkaran, Tingey, Aubrecht and Hande2020; Kelly, Hande, et al., Reference Kelly, Hande, Dansereau, Aubrecht, Martin-Matthews and Williams2020; Kelly, Jamal, Aubrecht, & Grenier, Reference Kelly, Jamal, Aubrecht and Grenier2020). This analysis highlights the themes identified among program users in the SFMC program. To respect the day-to-day realities of people using home care services, we interviewed self-managers with or without a worker present, family managers with or without a program client present, and program clients with or without a family manager present. The 24 user interviews therefore represent 3 self-managers (1 interview included a worker), 21 family managers (5 interviews included an older adult client), and 1 older adult program client who was interviewed in the absence of the family manager. In this article we focus on the experiences of family managers.

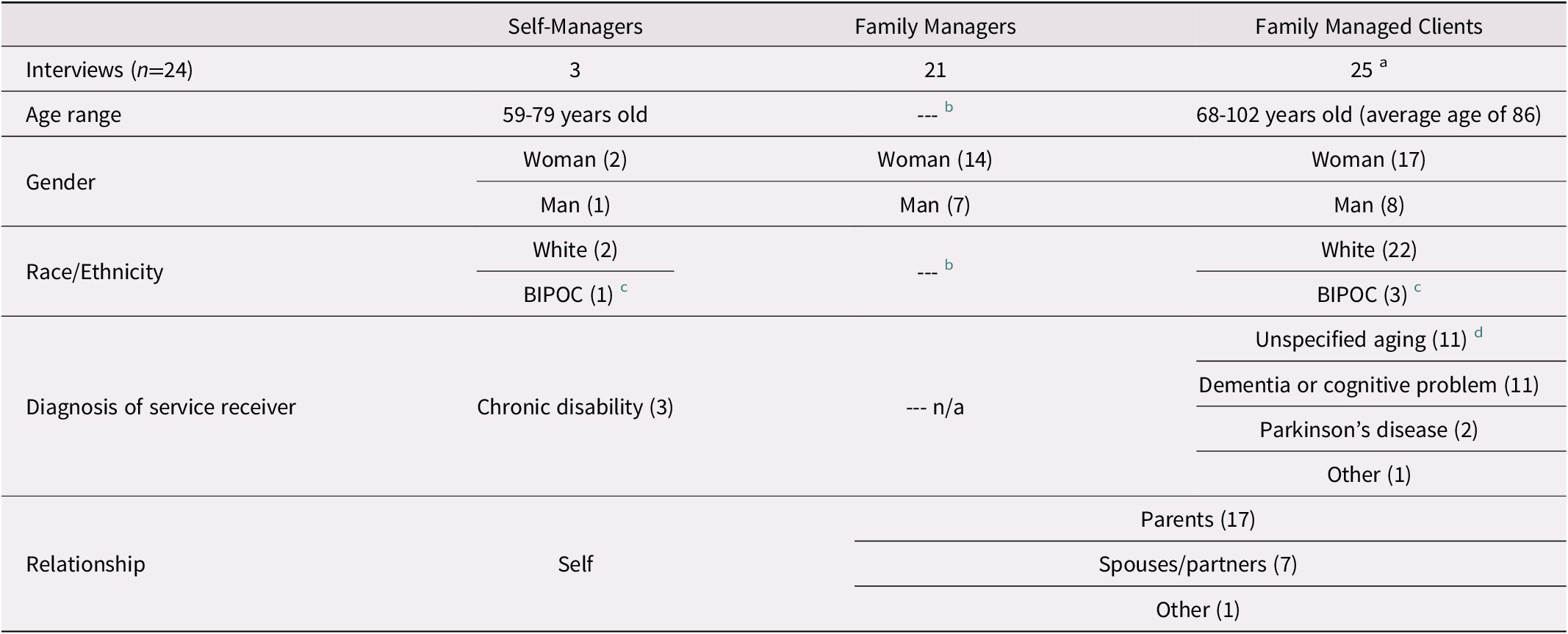

Participants were recruited through direct mail-outs facilitated by regional health authorities. Audiotaped semi-structured interviews were conducted by one or two trained research staff between February and October 2018, and were in person whenever possible, otherwise interviews were conducted by phone. Participant characteristics and the relationship between the home care client and care manager are provided in Table 1. Interviews ranged from 45 to 75 minutes and asked participants about their support needs and experiences such as What is a typical day like? opinions such as What are the advantages and disadvantages of the SFMC program? and employment issues such as How do you find workers? and Have you ever had to deal with conflict with your workers? Participants were given the option of being assigned a pseudonym or remaining anonymous, and we respect their choice when quoting the interviews.

Table 1. Participant demographics, diagnosis of service receiver, and relationship of care managers and clients

Note.

a Four family managers were arranging services for two people, either both parents or a spouse and a parent.

b We did not ask family managers to report their age or ethnicity.

c BIPOC refers to black, Indigenous, or person of colour, and white includes people self-identifying as Caucasian, European, Canadian, and Jewish.

d Unspecified aging indicates that the participant did not specify the reason for needing support other than aging, or that there were multiple complex care needs related to aging.

Data were analyzed by two coders using Dedoose software, using the techniques involved in iterative thematic analysis (Belotto, Reference Belotto2018; Huberman & Miles, Reference Huberman and Miles2002; Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994; Morse, Reference Morse and Morse1994). For more in-depth information on the overall research rationale, recruitment, and analysis see Kelly, Hande, et al., Reference Kelly, Hande, Dansereau, Aubrecht, Martin-Matthews and Williams2020. The study was approved by Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba (reference number: HS20640) and the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (reference number: RAAC 2017-022), and by letters of support from the remaining Regional Health Authorities in Manitoba.

Findings

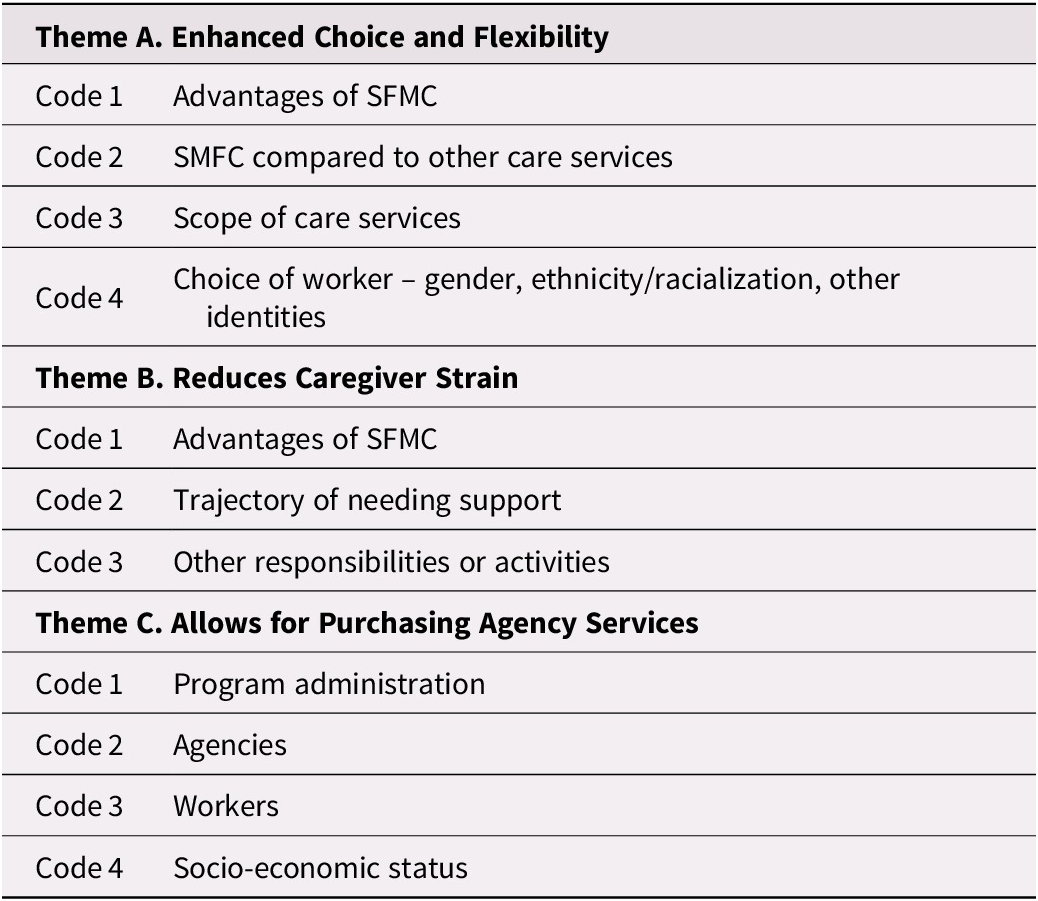

We identify three themes in the interview data: (1) DF home care enhances choice and flexibility for older people and their caregivers, (2) choice and flexibility reduce caregiver strain, and (3) agency services reduce administrative burden. Table 2 shows the main themes (axial codes) generated through qualitative synthesis of open codes.

Table 2. Themes from family manager Interviews

Note. SFMC = self and family managed care.

Enhanced Choice and Flexibility

Enhanced choice and flexibility is a strong thematic concept among the family-managed participants in our study. In Canada and internationally, choice is a common performance measurement for disability services (O’Keeffe & David, Reference O’Keeffe and David2020) and is positioned as pivotal for quality home care and other aging in place policies (Dalmer, Reference Dalmer2019). Self-managed services in DF aim to encourage greater choice and control (Lakhani, McDonald, & Zeeman, Reference Lakhani, McDonald and Zeeman2018) This key theme is woven through the subthemes of avoiding residential care, choice of worker and care continuity, and better care quality.

Avoiding residential care

The choice and flexibility offered in DF was linked to avoiding—or at least postponing—entry into residential care. Participants had a dim view of the quality of care provided in residential care settings, as exemplified by Shoshana, managing care for her 95-year-old father and recently deceased mother:

Shoshana: [being a family manager] is a lot of work, but to keep a parent in their home when they want to be in their home, and the home is safe, is just such a superior quality of life … to keep our parents in our home, they’re staying healthier because they’re not getting pneumonia and they’re not picking up the infections that you would get in a group setting.

Many of the care managers in our study argued that DF home care provided an opportunity for community-based care that was inherently superior to institutional living, and that it was their duty to keep their family member in a home setting. For example, Mary-Anne, managing care for her mother, commented:

Mary-Anne: Everyone my age with their aging parents thinks sooner or later I’ll stick them in a nursing home. It annoys the hell out of me! I tell people about this, I say, “No! If you get this [family managed care] and can maybe subsidize a little [with your own money], they never have to go in a nursing home.

Adela, managing care for both her parents, spoke very favorably of family-managed care, recommending it to other caregivers:

Adela: Instead of putting them in a personal care home you can kind of have your own little personal care home right in their home. How great is that? That, to me, is excellent.

Lisa echoed this sentiment. Her father had been hospitalized for a 3-month stay, and she was frustrated with hospital staff who seemed to assume that residential care was inevitable:

Lisa: They just seemed to get in their minds … that they wanted him paneled for a personal care home.

Lisa advocated for her father, and they ultimately ended up using Manitoba’s DF program as the best option to avoid entry into a personal care home.

Choice of worker and care continuity

The ability to choose workers was an important benefit for participants. Clients of provincially delivered home care services in Manitoba could complain about a worker and request that they be replaced, but there was no procedure allowing clients to select their worker. In contrast, DF home care provided the family with control over who entered their home. DF home care also provided better care continuity, as Lisa, a family manager caring for her 99-year-old father with early-stage dementia, explained:

Lisa: You know, [regular home care workers] don’t develop that same little kind of camaraderie … you know, the same kind of routine too. I think people of all ages, most people like routine. They like to know what’s coming next and how. There’s something to a little bit of familiarity, and I think it’s really important with older people especially if they [have a] cognitive [impairment].

Participants valued continuity of worker for multiple reasons, including not needing to train new workers, workers knowing their way around the home, being familiar with client preferences, establishing comfortable routines, and developing rapport. These types of advantages resonated among all participants and, as articulated in Lisa’s excerpt, were particularly salient for family managers arranging care for people with dementia or cognitive decline.

Family managers in this study also showed a strong preference for workers with formal training, as summed up by Susan, a family manager for her 87-year-old mother:

Susan: They’re all health care aides that we’ve hired. And they have to show that. They always meet my mom in advance, and I have to get that comfort level from my mom.

Many participants spoke favourably of workers with foreign health credentials, and several family managers required that workers have, at minimum, a health care aide certificate.

The family managers in this study also gave high value to the quality of the relationships between the client and workers, and tended to look for workers with a “caring” personality. Miriam, a family manager arranging services for her 100-year-old father, looked for workers who were patient, tolerant, and compassionate: “They have to tolerate, I don’t know, grumpiness. They have to tolerate that.” Family managers often put a great deal of effort into matching workers with the personality and preferences of the person receiving support.

Choice of worker may be linked to gender preferences, particularly when services involved intimate care. According to the family managers in our study, older female clients tended to feel nervous about male workers helping them in the bath or with toileting, while older male clients did not care either way. The gendered aspect of choice in worker was typified in the following excerpt from Nathan, managing care for both parents:

Interviewer: Have you ever thought about hiring a male care worker?

Nathan: I had the opportunity, but we didn’t because of my mother.

Interviewer: She wouldn’t feel comfortable?

Nathan: Not at all.

Interviewer: Yeah. Has your father ever wanted a male care worker?

Nathan: They both walk around totally nude. I mean, these girls, I mean—he doesn’t care. They clean him up, they put him in the shower. He just totally doesn’t care.

Racial and/or ethnic background is another dimension of choice of worker that we explored in our interviews. For all participants, many or most of their workers were people of colour and/or newcomers to Canada. Family managers most often indicated that they (and the client) appreciate diversity, as explained by Lisa, a family manager for her 99-year-old father with mild dementia:

Lisa: Oh, yes, there are immigrants. There’s a black worker, there’s a couple of our Indigenous people. Younger ones, middle-aged ones and some near retirement and some who have been home care workers, some who have worked in personal care homes. Yes, it’s quite a range actually. And actually, he finds them interesting.

Sometimes, however, cultural differences conflicted with the care expectations of the family. Craig, whose wife had advanced dementia, managed a team of four workers who were all newcomers from a variety of countries. One of the workers had religious beliefs prohibiting her from taking his wife to a warm water therapy pool:

Craig: One worker comes from a faith community that really does not allow wearing bathing suits, or going to the beach, or being in a public place where you see half-naked people. [This is a problem] if I want her to take my wife swimming.

Craig wanted his wife to exercise at the pool every day and went into detail regarding the complexity of setting worker schedules and even describing the swimwear choices of the other workers, finally declaring:

Craig: … like internally myself, like I’m explaining what the course of action I’ll do is not push too hard here and say, oh, okay fair enough, six [days] out of seven is pretty good. And if I want to take her on the seventh day, well maybe I’ll have to do it myself, you know, yeah.

Craig brought up this the topic repeatedly during his interview, and discussed the matter at some length each time, indicating that the issue was not yet resolved.

Some family managers hoped to hire workers of the same ethnic and cultural background as the client, what Cranford (Reference Cranford2020) refers to as “non-family co-ethnics.” This desire was expressed as something that would be “nice” or “ideal” but not necessary, and was most evident among families that were themselves from a minority cultural or ethnic group. For example, Shoshanna’s Jewish father previously had workers who were tied to the Jewish community, whereas his current workers were all Filipino:

Shoshanna: My dad is Jewish and some [of his previous workers] were also working in a Jewish old folks’ home so they’d bring the gossip. So, he loved that, so they interacted at that level. But now this [new agency we have switched to] only hires Filipinos … You know, I’m looking for someone who’s got integrity, who can interact with dad, you know, who can cook and can look out for him.

Participants reported that cultural matching was a relatively unimportant factor in the framework of qualities they looked for in their workers.

Rather than racial or ethnic identity, most of the family managers in our study expressed concern over language fluency. In the following excerpt, a family manager explained that his 86-year-old mother with dementia was losing her communication skills and could not understand people speaking with strong accents:

Anonymous: We’ve had some healthcare aides that are new Canadians and Mom can’t understand them. They speak English, of course, they’re going through the process, but their accents are a little strong. We had a person like that and we said, “We love you as a person, but Mom has to understand you.”

The emphasis on language fluency in our data hinted at subtle racism among some participants; however, it predominantly reflected the fundamental importance of listening, understanding, recognizing, and responding in care, and communication skills influenced family managers’ perceptions of care quality.

The ability to choose workers based on a variety of factors was important, as summed up by Shoshanna:

Shoshanna: You know, it’s your pros and your cons and so, yes, you have a cultural aspect, you have a language aspect, and you have a personality aspect.

Choice of worker and care continuity were key aspects of family manager and client satisfaction with DF services.

Better care quality

Most participants insisted that the flexibility of arranging their own services and schedules and the ability to choose their own workers resulted in much better care quality through DF home care than through the “traditional” services delivered by the regional health authority. For example, Sarah, an 89-year-old client with her daughter acting as family manager, previously received home care delivered through the health authority but needed assistance caring for her pet.

Sarah: I was at home care first. I have a little dog, and when I fell and injured my back I needed someone to walk the dog…This firm [home care agency] offered to walk the dog. So I changed from RHA [regional health authority] home care to SFMC and this firm that I now use, because they were willing to walk my dog for me.

Family managers spoke positively about the benefit of scheduling care at convenient times and arranging activities to accommodate the routines and habits of the older adult. Steven, a 77-year-old caring for his spouse with Parkinson’s Disease, found that this flexibility made a “huge” difference in his own life, allowing him to attend sporting events, participate in golf, and “hang out” with friends and family:

Steven: I can change the schedule in a very short order …if something comes up, I mean I can phone on Monday and say on Wednesday I have to go to da-de-da-de-da…

Interviewer: This has made a big difference in your life?

Steven: Oh huge, huge, it really has.

All family managers in this study were highly appreciative of the difference it made for the client and for their own lives when they had the authority to assign work as needed, to schedule workers when it was convenient, and to have workers stay as long (or as briefly) as needed.

Reduced caregiver strain

The family managers in this study were under significant strain. Older and spousal family managers reported a narrowing of their social and community interactions, whereas younger and intergenerational family managers described stress caused by unpredictable demands on their time and difficulty juggling care with work and other family responsibilities. The choice and flexibility offered by the SFMC program provided them with the opportunity to reduce their own stress across a variety of domains including scheduling and determining the work being done, worker continuity and building trusting relationships, and confidence in the quality of care being delivered. It is important not to overstate this, as many of the participants in this study nevertheless expressed being overwhelmed by the responsibilities of caring for their family member.

Family managers tended to experience increasing social isolation, not necessarily because of their role as a care manager, but because of their role of caregiving more broadly.

Clarice (caring for her husband): We can’t go to church anymore, I mean it’s impossible […] we used to go on cruises, we used to go on holidays, we can’t.

Richard (caring for his wife and previously for his mother): I’m actually trying to get [some respite] … so I can do grocery shopping or go to the bank, or just actually get the hell away from home for a little while […] I’m slowly being swallowed up in the care industry with the ladies I love. I’m disappearing under the waves.

The sense of disappearing or of losing themselves to the role of caregiver was most apparent for spousal family managers, but there were also repercussions for younger family managers.

Working-age participants struggled to balance care duties with paid work, and when “push came to shove” some sacrificed their income and career rather than the well-being of their family member. Caring for both parents, her mother with schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease and her father with multiple chronic conditions including lung disease and diabetes, an anonymous co-resident daughter explained:

Anonymous: The case coordinator said to me that Mom wasn’t going to get any more than 15 hours a week. And I said, “Well, I work. I can’t look after her if I’m working!” And they said, “No, that’s all we’re giving you.” And I had to deal with it and it was very stressful.

This participant had recently left “a really good job” as a research statistician, saying “I was forced into this early retirement. That’s how I feel anyway.” Guy, managing care for his wife, similarly described the effect on his job:

Guy: [if my wife] wasn’t dependent on somebody, I think I would still be working, because my job involves travel … and I found I couldn’t travel anymore for work, because of overnight issues. And that was why I thought I should leave my job.

Leaving paid work to provide unpaid care was a common response for caregiver-employees when the demands of providing care outweighed the available resources and supports.

All of the family managers in this study were also caregivers, and we have briefly touched on a few of the many excerpts from our participants that align with the established literature on caregiver burden and strain. The choice and flexibility offered by DF home care allowed family-managers to find ways to reduce the stress that they were experiencing across multiple dimensions in their role as caregiver. An important aspect of this flexibility was scheduling services at times that were most suitable. Our participants indicated that having more control over the care schedule resulted in more reliable services, which in turn relieved a lot of their stress. Steven, managing care for his wife, explained in some detail the various ways that having reliable services in combination with a convenient schedule reduced conflict and frustration:

Steven: [With the health authority] I never knew when the people would come. Some of them didn’t know what they were doing… I’d phone in and I’d say “You know, I always understood here that this home care program you had was supposed to help me relieve my stress in the situation I’m working in here. But I’ve got to tell you, you’re causing more stress than you’re relieving!”… now I kid with my golfing buddies, I say “Whenever I would go golfing with you before I always had a story to tell you about the chaos I’m having. Now, with family managed,” we laugh about it, you know, and I say, “you know, it’s boring now because I don’t have any issues.”

The improved flexibility and reliability of services reported by all participants relieved the frustrations associated with rigid services.

Family managers also spoke about worker continuity as a significant benefit of DF home care, allowing them to trust the quality of care received by their family member in their absence. Margaret, managing care for her father, explained how a sense of trust relieved a lot of worry:

Margaret: When [worker] comes around 9:00, I can either go to the gym, run errands, go shopping, do whatever and I can come back at whatever time I need to. I don’t worry. If it’s somebody else, I either wouldn’t go or I would be stressed out all the time I was away.

The flexibility offered by DF home care allowed family managers to organize services with consideration of their own lives and needs, and provided a great deal of relief in terms of caregiver strain. Additionally, the reliability and continuity offered through DF home care allowed family managers to trust in the quality of care being provided, significantly alleviating worry and stress. Family managers reported that DF home care was a significant support not only for the family member needing services, but also for themselves in their role as caregiver.

Agency Services Reduce Administrative Burden

DF home care originally promoted a direct-hire approach in which support workers were found in the local community (often without training) and through personal social networks (DeJong, Reference DeJong, Crewe and Zola1983). This has changed over time, and with the growth of a private care market leading to increased availability of agency services. Just over 60 per cent (13 of 21) of the family managers in this study purchased services from home care companies. In this theme we explore the role of private agencies in the context of DF home care and describe the subtheme of the economic costs of care. It is of note that agency use is not a universal feature of DF programs in Canada, as some do not allow program funds to be used to purchase agency services (Kelly, Jamal, et al., Reference Kelly, Jamal, Aubrecht and Grenier2020).

One of the first challenges in a direct-hire model of DF home care is finding people to hire, and this was experienced as particularly daunting for family care managers new to the role. Of the family managers who hired directly, some found their workers through online classifieds, whereas others relied on their social networks and word of mouth. Interestingly, many family managers relied on the social networks of their workers rather than their own networks.

Susan: We put one person that we hired in charge of finding the other people, and she really manages within that group to make sure that we have 24/7 covered off. And that’s why we have backup people as needed.

Deborah: I think that we just struck gold literally with the woman that has been with us since the beginning, and from there we’ve just been lucky because she would never bring us anybody who wasn’t a stellar person and completely honest, and we never had to worry about theft of any kind or misconduct of any kind … [if not for] this one woman that’s been with me, I would most assuredly have to go to an agency, I would not have resources.

The issue of finding workers was one of the key reasons that the majority of family managers opted to purchase agency services.

Miriam: You know there’s a limit to my capacity to reach out and just find other people like that on a one-by-one-by-one basis … however many networks I have, I couldn’t reach far enough to start hiring individually.

Mary-Anne: I say to people, you don’t have to hire your own people! You just have to hire the agency and they hire the people.

Family managers were also attracted to agency services because they shouldered the complexities of scheduling. For example, John was daunted by the idea of taking on such a task, and instead purchased agency services for his 98-year-old aunt:

John: I’m assuming it would be a full-time job scheduling, hiring people. Maybe it would work? … You just don’t just have one person, you might have a few people, and to manage that would be very difficult for me so I would probably always use a private company.

Some participants who hired directly found creative means to reduce their administrative workload. Deborah arranged care for her 82-year-old mother and, as we mentioned previously, depended on the social networks of one of her workers to find new workers. She assigned this worker to the role of “supervisor” and relied on her to do the scheduling:

Deborah: My regular fulltime girl has sort of risen to sort of supervisor role and she lays out the schedule and then I do the payroll from the schedule. And she’s the one that’s helped me get all the staff.

Family managers explained that agencies also eased their concerns about managing payroll, including calculating holiday pay and generating tax forms for their workers. Most of the family managers who purchased agency services lacked expertise in these administrative functions and seemed intimidated by the idea of taking fiduciary responsibility. A few indicated that they simply had no time or interest in taking on such tasks.

Olivia: If you’re hiring family or a friend across the street, that’s when it does get, I’m sure, get complicated. But with a company like this, they pay all the benefits and they look after all of that. So all I have to do is report back on the money that I’ve spent.

Anonymous: I do payroll for a living. I didn’t want to do it in my spare time! And to have one or two people, it’s not worth all the hassle you have to go through to get a tax number and everything else. And then, I would have to look for, you know, to have spare people. I work fulltime so I didn’t want the hassle. I wanted somebody that would look after all that. Yeah, so that’s how we did it and it works great.

Some of family managers who hired directly outsourced the accounting work to a payroll company. Nathan, a family manager arranging care for both parents advocated for this approach:

Nathan: What advice would I give? For sure, use a payroll company … It’s just a time a saver and stress and everything with our government, with the taxes and deductions and T4’s. So for sure, get a payroll company.

In other cases, family managers hired workers as part of the gig economy rather than as official employees. For example, Mary-Anne purchased agency services and also hired one direct worker for her 91-year-old mother:

Mary-Anne: I’m hiring her as a private contractor, she’s not my employee, I don’t have to take deductions, so I just pay her and she has to do her own. She’s a private contractor.

Family managers found creative ways to avoid various aspects of administrative burden associated with the SFMC program. Strategies to manage their care included downloading responsibilities onto workers, outsourcing to a payroll company, or avoiding the role of employer by purchasing agency services.

The distinction between hiring directly and purchasing agency services affected the experiences of people using DF home care in subtle ways. Agency services placed some constraints on flexibility, as each organization had policies in place to reduce overhead or standardize their labour force. These included advance notice periods for schedule changes, fee schedules based on worker education level, worker substitution policies, minimum booking times, or restrictions based on time of day (such as no overnights offered). All participants in our study who purchased agency services did so to avoid administrative burden, and all reported that agency services were preferable to the highly constrained services offered by regional health authorities.

The Economic Costs of Care

Although we did not collect direct data on participant wealth or income, evidence relating to financial and social resources was coded. Based on our analysis, family managers in this study were either themselves financially secure or “well-off,” or the family member they supported had amassed a comfortable savings. Three quarters (16 out of 21) of the family managers reported paying out-of-pocket for services in addition to using SFMC funds. For example:

Susan: We have 24/7 covered off and that’s why we have backup people as needed … it’s costing us thousands of dollars a month to have our workers over and above what we’re compensated by the government.

John: [The cost of her care] is over the limit of what the SFMC program pays for, so funds are paid from the program and additional funds are paid privately.

Shoshanna: As a family we were very pleased just to subsidize the hourly wage to be competitive. It is difficult, so you have to have money to be able to subsidize.

At the time of data collection, funding for Manitoba’s SFMC program was capped at a maximum of 55 hours of service per week. Many families spent extra money to purchase additional services. Others “covered the difference” to pay for their full assessed service hours, as many private agencies in Manitoba charged more per hour than was funded through SFMC. Two family managers reported providing extra funds to increase the wages of their directly hired workers.

Discussion

Our findings based on the SFMC program emphasize the shifting frame of DF home care, which originated to serve self-managers but is now increasingly being taken up by family managers arranging services on behalf of an older adult. The findings of this study indicate that family managers and older people appreciate that DF home care provides them with the authority to direct various aspects of their day-to-day lives. However, the disability literature and the Independent Living philosophy additionally emphasize independence and autonomy, positioning self-directed support services as a human right and a requirement to help address ableism and oppression (Batavia, Reference Batavia2002; Carr, Reference Carr2011; DeJong, Reference DeJong1979; Watson, McKie, Hughes, Hopkins, & Gregory, Reference Watson, McKie, Hughes, Hopkins and Gregory2004). These ideals are not evident among the family managers in our study. Family managers take the reins not because they want control per se, but in response to inappropriate or inadequate public services. The emphasis among family managers is to help maximize the quality of life an older person who is experiencing reductions in independence, and keep them out of residential care.

Choice of worker and care continuity form a cross-cutting theme interacting with the themes of better care quality and reducing caregiver strain. Continuity of worker is particularly emphasized across an array of dimensions relevant to care quality including familiarity, rapport, and trust. As argued by care ethics, the characteristics of care relationships are directly associated with care quality (Cloutier, Martin-Matthews, Byrne, & Wolse, Reference Cloutier, Martin-Matthews, Byrne and Wolse2015; Eustis & Fischer, Reference Eustis and Fischer1991; Held, Reference Held2006; Horner, Reference Horner2020; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). There are therapeutic possibilities both in giving and receiving care (Bondi, Reference Bondi2008), and workers also appreciate the ability to choose whom they work for (Woolham et al., Reference Woolham, Norrie, Samsi and Manthorpe2019). DF programs put power in the hands of individuals, allowing them to take some degree of control over the care context. This is in sharp contrast to highly bureaucratized and regulated care services, as is the situation with public home care services in Manitoba.

Our findings indicate that family management and DF home care for older people reduces caregiver strain caused by inflexible and standardized services that do not value social support and do not recognize the importance of relationships. The family managers in our study who chose to purchase services from private care agencies indicated that they did so to avoid administrative burden, and were willing to accept some reduction in service flexibility in return for administrative support. This finding suggests that family-managed care shifts caregiver strain in subtle ways. That is, DF home care simultaneously allows caregivers to feel less stressed as a result of improved suitability of time, task, and quality of life, but does so while increasing stress in the domains of handling finances and organizing and coordinating services.

In DF home care, the managerial responsibilities placed on family caregivers are brought to the foreground with their title of “family manager”. This term formalizes the role of caregivers as information mangers (also referred to as care coordinators, life coordinators, and system navigators) (Anker-Hansen, Skovdahl, McCormack, & Tønnessen, Reference Anker-Hansen, Skovdahl, McCormack and Tønnessen2018; Funk, Dansereau, & Novek, Reference Funk, Dansereau and Novek2019; Rosenthal, Martin-Matthews, & Keefe, Reference Rosenthal, Martin-Matthews and Keefe2007; Sims-Gould & Martin-Matthews, Reference Sims-Gould and Martin-Matthews2010) and highlights the complex responsibilities taken on by informal caregivers. Policies that aim to reduce caregiver strain should, at minimum, recognize the obligation to orchestrate care that is placed on informal caregivers. Finally, there is a need to better support the informational needs of caregivers if they are to successfully perform the duties of care management.

Our analysis suggests that increasing the use of private care agencies may come at a significant social and political cost. Agency workers are typically paid less than directly hired workers, and tend not to have the limited protections of provincially employed and unionized workers (Kelly, Jamal, et al., Reference Kelly, Jamal, Aubrecht and Grenier2020). Although there is movement towards unionization in some contexts, such as in Ontario, it is an ongoing challenge to form collectivity among non-professional care workers (Cranford, Reference Cranford2020). The choice offered to families and clients using DF home care brings other potential risks for workers, particularly among those that work directly for a family. It is well established that care work is both feminized and racialized (Bourgeault, Atanackovic, Rashid, & Parpia, Reference Bourgeault, Atanackovic, Rashid and Parpia2010; Conradi, Reference Conradi2020; England & Dyck, Reference England and Dyck2012; Kelly, Reference Kelly2017; Sethi & Williams, Reference Sethi and Williams2015) and it is, unfortunately, common for care workers to experience violence, sexism, and racism (Cranford, Reference Cranford2020; Funk, Spencer, & Herron, Reference Funk, Spencer and Herron2021). This is of particular concern for workers in the private spaces of home who are away from the eyes of supervisors, and perhaps even more concerning for directly hired DF workers who may be placed in a position where their potential abuser is also their employer.

The use of public funds to purchase agency services may also be implicated in larger structural changes in care systems. For example, the use of agencies under DF home care in the context of Manitoba, which has a strong public home care system, means that families are essentially replacing public services with private services. Such movement towards privatization has multiple potential repercussions, including increasing inequity among older people of differing economic backgrounds in need of home support.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

As raised by Askheim et al. (Reference Askheim, Andersen, Guldvik and Johansen2013), it remains difficult to assess whether older people who rely on family managers are exercising choice and control, or even if this is as important to them as it is to younger disabled people (Purcal, Fisher, & Laragy, Reference Purcal, Fisher and Laragy2014). Whether or not an older person is exercising choice in their daily life is not possible to assess in an interview with family managers, which presents a clear limitation. A related limitation involves an analysis of the meaning of independence according to life stage, as raised by Woolham and colleagues (Reference Woolham, Daly, Sparks, Ritters and Steils2017). We believe that the difference between managing for oneself and having a family manager organizing services on your behalf is an important distinction in terms of independence and other related concepts of autonomy and control, but our data lack the perspective of the older adults who are having services arranged by family managers.

We also note that we lack family manager participants from lower income groups. We interpret this as a finding rather than a limitation, suggesting that DF home care may produce unintended inequity in access, bringing to attention the need for more research in this area. For example, cross-sectional research is needed to confirm socio-economic status levels across various populations using DF home care, and there is a need for in-depth research specifically examining uptake of DF home care among lower-income older adults.

The politics of client choice, particularly in the private setting of the home, has important implications for the well-being of workers, and we need to listen to the voices of workers in the DF model to understand their experiences. It is vital to always be aware that the care labour force is itself marginalized, feminized, racialized, and notoriously underpaid (Atanackovic & Bourgeault, Reference Atanackovic and Bourgeault2013; England & Dyck, Reference England and Dyck2012; Parreñas, Reference Parreñas2000; Sethi & Williams, Reference Sethi and Williams2015; Weller, Almeida, Cohen, & Stone, Reference Weller, Almeida, Cohen and Stone2020; Zagrodney & Saks, Reference Zagrodney and Saks2017). More research is needed on how to balance the rights of people in need of support with the rights of workers providing support services.

Conclusion

Our study shows that family managers and older clients benefit from DF home care in ways that both echo and diverge from how younger self-managers with disabilities benefit. If DF home care was envisioned as an alternative to institutionalization, this is certainly happening under family management. However, our discussion of caregiver strain highlights the need for health systems to better recognize and value informal care.

In terms of the concrete policy implications of our study, there is an opportunity for public home care services to learn from DF home care. Home care systems should seek ways to allow more flexibility in the tasks that workers may perform, encourage worker continuity, honour the varied lifestyles and preferences of clients and families, and acknowledge the authority that individuals have in their own home. Such flexibility requires a shift in thinking away from the task orientation of physical and medical care towards a more relational orientation of social support. It also requires that different policy structures be put in place to protect workers from abuse and unfair treatment by demanding and “entitled” clients.

Most family mangers show little interest in taking on the financial and administrative responsibilities associated with hiring their own workers. It is important that policy makers take this into account if they are considering expanding DF home care to serve a greater proportion of older adults. To benefit a wider array of people, governments and health authorities might consider taking on a more “hands on” approach, such as having private agencies bill the government directly, as occurs in New Brunswick and some other provinces. Alternatively, health systems might consider having families or workers submit time sheets to be paid through a government payroll scheme, as occurs in Quebec. This form of administrative support might encourage direct hiring from local networks, which would help tackle issues of access in rural or underserved locations. Such creative means of providing support would also reduce the administrative burden experienced by both family managers and self-managers, demonstrate some level of recognition for caregiver needs, and potentially encourage uptake by economically disadvantaged groups.

What makes family management in DF home care different from other forms of home care is that publicly funded formal service delivery is coordinated by informal caregivers rather than by system professionals, and caregivers often do this work with minimal training and support. This level of responsibility does not appeal to all families, but is an attractive home care option for those who desire the flexibility to control their own schedules and workers. In taking on the role of family manager, caregivers become engaged in an act of balancing the benefits of flexibility with the burdens of administering care services.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge ongoing administrative support from Dr. Yuns Oh and acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Mary Jean Hande, who was involved in the data collection for this study. Finally, the authors acknowledge the time and contributions of the research participants who make this work possible.