In 1684, Lourenço da Silva de Mendonça from the kingdom of Kongo in the IndiesFootnote 1 ‘arrived in Rome to take up an important role for Black peoples’.Footnote 2 That role was to bring an ethical and criminal kufundaFootnote 3 (case) before the Vatican court, which accused the nations involved in Atlantic slavery, including the Vatican, Italy,Footnote 4 Spain and Portugal, of committing crimes against humanity. It detailed the ‘tyrannical sale of human beings … the diabolic abuse of this kind of slavery … which they committed against any Divine or Human law’.Footnote 5 Mendonça was a member of the Ndongo royal family, rulers of Pedras (Stones)Footnote 6 of Pungo-Andongo, situated in what is now modern Angola.Footnote 7 He carried with him the hopes of enslaved Africans and other oppressed groups in what was a remarkable moment that, I would argue, challenges the established interpretation of the history of abolition.Footnote 8

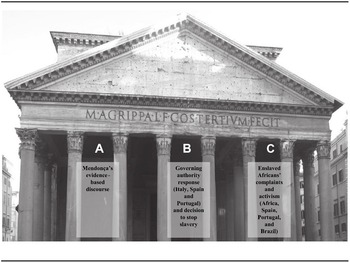

Legal, moral, ethical and political debate on the abolition of slavery has traditionally been understood to have been initiated by Europeans in the eighteenth century – figures such as Thomas Buxton, Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp, David Livingstone and William Wilberforce.Footnote 9 To the extent that Africans are recognised as having played any role in ending slavery, especially in the seventeenth century, their efforts are typically confined to sporadic and impulsive cases of resistance, involving ‘shipboard revolts’, ‘maroon communities’, ‘individual fugitive slaves’ and ‘household revolts’.Footnote 10 Studies of these cases have never gone beyond the obvious economic disruptions caused by enslaved people resorting to poisoning, murder and attacks on plantations and their masters’ household properties. Even those former enslaved Africans who gained their freedom through sheer endeavour and subsequently argued in the strongest terms for the abolition of slavery in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such as Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano, were seen as limited in scope, without international imapct and reliant on their European counterparts.Footnote 11 Curiously, to date, no historians of slavery of West Central Africa, Africanists or Atlanticists have researched the Black Atlantic abolition movement in the seventeenth century; and those who have attempted to engage with the debate often conclude that any action driven by Africans was a localised endeavour.Footnote 12 No historian has yet provided an in-depth study of the highly organised, international-scale, legal court case for liberation and abolition spearheaded by Lourenço da Silva MendonçaFootnote 13 (see Figure 1), or as Mendonça called it the ‘complaint (reclamazione)Footnote 14 … complaining about Justice (reclamando Giustitia)’.Footnote 15

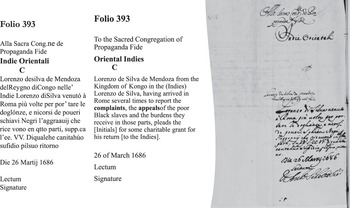

Figure 1 Mendonça’s Second Legal Challenge ‘Second Complaint’ – [Seconda Reclamazione] APF, SOCG. vol. 495a, fl. 58.

The letter (Figure 1) clearly indicates that Mendonça’s first legal challenge was a court case, and that he presented the case again, as the ‘second complaint’ demanding justice (‘Requesting Justice’) to the Office of Propaganda Fide, or ‘General Congregation’, which was charged with dealing with any issues arising overseas.Footnote 16 The document is undated, but it is clear that it was a continuation of his earlier legal challenge. It reads: ‘S:ma Mad. Chiesa Reclamando Giustitia’ ‘Beatist:mo Pd:re Em.mi e Rev.mi Sig.ri’ [Second appeal to Our Lord and to Saint Mother Church Requesting Justice], ‘Beatist:mo Pd:re Em.mie Rev.mi Sig.ri’ [Most Blessed Fathers, Most Eminent and Most Reverend Lords].

In this book, I examine in detail how Mendonça and the historical actors with whom he was involved – such as Black Christians from confraternities in Angola, Brazil, Caribbean, Portugal and Spain – argued for the complete abolition of the Atlantic slave trade well before Wilberforce and his generation of abolitionists.Footnote 17 Providing an in-depth analysis of Mendonça’s abolition movement, this book offers new perspectives on the abolition history of the seventeenth century and the associated debates that re-emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 18 It reveals, for the first time, how legal debates were headed not by Europeans, but by Africans.

Drawing on new data uncovered in a variety of archives around the world and never before used by historians of the Lusophone Atlantic, this book links Mendonça’s activity to that of New Christians (Jews converted to Christianity, also known as the ‘Hebrew Nation’) and the Indigenous Americans (an Indigenous people who inhabited what is today known as Brazil before the Portuguese arrival).Footnote 19

I argue that there is an important and previously overlooked connection between Africans seeking the abolition of slavery and the New Christians and Indigenous Americans in their common search for liberty and understanding of how the denial of religious freedom was connected with the denial of enslaved Africans’ humanity.Footnote 20 I also contend that by allying himself with these different constituencies in the Atlantic, Mendonça carried his abolitionist message of freedom far beyond Africa.Footnote 21 His claim for liberty was universal: it went beyond the predicament of enslaved Africans to include other oppressed groups in Africa, Brazil, the Caribbean, Portugal and Spain.Footnote 22

To fully comprehend Mendonça’s work, it is crucial that we understand from the outset that the enslavement of Africans was part of the Portuguese conquest of West Central Africa, where Mendonça was born.Footnote 23 Slavery went hand in hand with conquest in Portugal’s encounter with Central or West Africa, and the enslavement of Angolans was inseparable from Portuguese military aggression in the region.Footnote 24 From the beginning of Portuguese settlement there in the mid-sixteenth century, war was waged against the West Central African people.Footnote 25 This was the catalyst for the enslavement of ordinary civilians.Footnote 26

If we are to grasp the rationale behind the capture of enslaved peopleFootnote 27 in the region and understand how they were obtained, it is crucial to recognise the role played by the Muncipal City Council of Luanda, which regulated the shipment of the enslaved Angolans sent to Brazil.Footnote 28 Indeed, it is impossible to understand the significance of Mendonça’s court case without taking account of the involvement of the Muncipal City Council of Luanda in the slave trade. Central to the argument of this book, then, is the story of the destruction of Pungo-Andongo and the death of its last king, João (John) Hari II, who was Mendonça’s uncle.Footnote 29 Exiled as prisoners of war, Ndongo’s royals, including Mendonça, his brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins, were sent first to Salvador in Bahia, then to Rio de Janeiro and other captaincies in what is nowadays Brazil, and finally to Portugal.Footnote 30 Crucially, to fully understand the involvement of sobas (Angolan local rulers) in the slave trade in Angola and perhaps elsewhere in Africa, I contend that it is necessary to take into account the introduction in 1626 by Fernão de Sousa, the Portuguese governor in Angola, of baculamento, a tax payment of enslaved people, in place of encombros, a tax payment in produce.Footnote 31 This is a piece of new data that has not been used by historians of West Central Africa, Africanists and Atlanticists. I argue that it had far-reaching consequences for the historiography of the region in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unaware of this legislation, West Central African historiography on ‘taxation’, ‘wars’, ‘debt’ and ‘legal practices’ has unwittingly been prevented from truly understanding the reasons for and methods of enslavement.Footnote 32 These historians of West Central Africa have remained ignorant of Sousa’s introduction of the baculamento. Subsequent governors and their captains in the presidio (Portuguese outpost) in Angola used the baculamento for centuries to naturalise the Atlantic slave trade. And the baculamento has remained obscure until now; most West Central African historians have taken it as accepted wisdom that slavery was an African practice,Footnote 33 and the idea that Africans colluded in Atlantic slavery has never been challenged.Footnote 34 Generations of scholars have studied systems of ‘taxation’, ‘wars’, ‘debt’ and ‘legal practices’ without interrogating the the Portuguese institution of baculamento, which overrode local practices; instead, blame has been placed on the Angolan institutions. All Angolan soba allies of the Portuguese conquest were obliged to make a payment of 100 enslaved people annually to Portugal. This Portuguese taxation, which was named after the local baculamento practiceFootnote 35 – a tribute system – profoundly disrupted the Angolan socio-political and legal system and resulted in social upheaval. Communities and their rulers were turned against each other, a new local judicial procedure was imposed that served the interests of the Atlantic slave trade, putting judicial officers in local courts in Angola to adjudicate local cases in their own interest – what Kimbwandende K. B. Fu-Kiau called a turning point in African governance and leadership in West Central Africa.Footnote 36

Following from this, I scrutinise the history of runaways to gain an understanding of how those who escaped enslavement in Angola, São Tomé and Brazil conceived their plight. Many enslaved peoples ran away in these regions because they rebelled against a system that dehumanised them, which Portugal had imposed upon them. While in Brazil, Mendonça may have had contact with communities there of such runaways, come to understand their suffering and connected his experience with theirs, especially those who joined Quilombo dos Palmares, one of the earliest, largest and most successful maroon communities in Brazil.Footnote 37

Looking at Mendonça’s later life and journey to Portugal, I argue that his stay in Braga and Lisbon helped him to form an alliance with the family of the apostolic notary in Lisbon, Gaspar da Costa de Mesquita, and the New Christians in Portugal.Footnote 38 Then I examine his journey, undertaken with the support of the papal nuncio in Portugal, to Toledo – where he formed a network with Indigenous Americans at the Royal Court of Madrid.Footnote 39 I argue that to understand Mendonça’s court case one must understand his family, who were coerced by the Portuguese into becoming involved in the slave trade. The weight of this history and the resulting psychological burden constituted one of the most compelling reasons for Mendonça’s journey to the Vatican and his deep desire to see the Atlantic slave trade abolished. He wanted the Atlantic slave trade to be tánuka, a term in his language, Kimbundu, meaning ‘to be torn, destroyed or shattered’.Footnote 40 Equally, he wanted all the other ill-treated constituencies such as the New Christians and the Indigenous Americans freed, due to ‘Pan-Atlantic’ solidary.Footnote 41

This book thus explores for the first time how enslaved Africans were part of a wider Atlantic economic network in the seventeenth century, encompassing Africa, Brazil, the Caribbean, Portugal and Spain. It examines how they used transatlantic connections to join with other oppressed groups so as to fashion a league of confederation to achieve freedom. In the following pages and before engaging with this account in detail, I briefly introduce the historical context of Mendonça’s court case by giving a first overview of the Portuguese Empire operation in Angola and Mendonça’s family tree and life story. I go on to discuss the studies and sources that I have used to analyse Mendonça’s work and historical context. I then explain the book’s methodology. This is followed by a detailed breakdown of the book’s chapters.

0.1 The Portuguese Empire Operation in Angola: Kings, Governors, Councils and Local Rulers

The Municipal Council of Luanda was founded on 11 February 1575 by Paulo Dias de Novais, a nobleman who was appointed as a captain and the first governor of Angola by the Portuguese Crown on 19 September 1571.Footnote 42 The council was the governing authority that ran the affairs of the Portuguese enclave in Luanda. Executive power in the Municipal City Council of Luanda lay with its governors, members, a senior crown judge, scribes, judges and war council (which had the power to veto wars in the region). The head of the council was the governor, directly appointed by the Crown in Lisbon. Aside from the executive body, the council had other functionaries, such as the apostolic notary.

Conquered, and subjected to Portuguese rule, Angolan kings and sobas loyal to the king of Portugal were made subject to annual tax payment in human beings in 1626, thus turning people into a currency.Footnote 43 This was particularly the case for Angolan kings, because ‘native’ soldiers were recruited directly from the region where the Portuguese had established control and maintained fairs (markets).Footnote 44 The Municipal Council of Luanda was charged with dividing land already conquered from the Angolans between the Portuguese and African war captains, so-called guerra preta.Footnote 45 The council was also responsible for paying the salaries of the governors, the soldiers and secular priests, and regulating trade and tax revenues.Footnote 46 On 19 November 1664, members of the Municipal Council of Luanda showed their power by lodging a complaint with the Crown that was adjudicated by the Portuguese Overseas Council, which dealt with all overseas affairs:

That the trade of the same Kingdom [Angola] consists only in the enslaved that is carried out in the lands of Soba’s vassals of His Majesty, that is, from presidios such as Lobolo, Dembos, Benguella, and from those that are mostly conquered by that government … that the most important thing that there is in that kingdom, which is in need of maintaining, is the Royal standard tax duty in slaves that they dispatch from the factory of Your Majesty. It is not that its profit is great, but also for being used for sustaining the Infantry, and to pay governors’ salaries of five presidios of hinterland, of secular priests in Kongo, and of other clergy of that kingdom, and other salaries, and budgets.Footnote 47

This clearly demonstrates that the City Council’s budget depended entirely on revenues from enslavement.Footnote 48 The slave trade in Angola was the lifeblood of the council and maintained the Portuguese project of conquest; without it, there was no Portuguese Empire. Hospitals in Angola were dependent on the slave trade for their existence, and so were education and missionary activities in the region.Footnote 49 The council interfered in local politics and elections, and particularly in the role of the local ngola (kings).Footnote 50

The Council of Luanda, which was composed mainly of Portuguese merchants and some retired soldiers who had fought wars in Angola, also exerted undue pressure on the sobas’ governance of their provinces.Footnote 51 They controlled the market and charged their pombeiros (local conquered traders, including enslaved people owned by the Portuguese) to carry trading into hinterland markets.Footnote 52 The City Council’s interests were often at odd with those of governors, the Portuguese Overseas Council and the Portuguese Crown.Footnote 53 Let us look now at the ruling royal family from which the City Council drew its influence and also at where Mendonça came from and his family tree.

Prince Lourenço da Silva Mendonça was probably born in the kingdom of Pedras of Pungo-Andongo, and certainly in Angola, but his date of birth and place of death remain unknown. He may have been twenty-two or twenty-three years old when he left Angola in 1671. He was a member of the Mbundu, one of the people groups in Angola.Footnote 54 Beyond this, not much is known for certain about his early life.

Pedras of Pungo-Andongo was the seat of the first Angolan allied to the king of Portugal, Philipe de Sousa, or Philipe Hari I (Ngola Aiidi), or Dom Henrique Rei do Pungo-Andongo, known in Angola also as Samba a Ndumba. He ruled for thirty-eight years.Footnote 55 Mendonça’s father was Dom Ignaçio da Silva,Footnote 56 the son of King Philipe Hari I; his mother’s name is unknown. He had three brothers: Simão, Ignacio and Ignacio (the two latter shared a name).Footnote 57

Within Angola, I have traced the royal family of Pungo-Andongo back to the celebrated Queen Njinga (1624–1663). Ngola Aiidi (Philipe Hari I) was her half-brother on his father’s side, as well as half-brother to King Ngola Mbandi; Cadornega’s work confirms this.Footnote 58 His mother was the third wife (Mocama or Mukama) of King Ngola Kiluanje Kia Ndambi.Footnote 59 However, a letter I discovered in the Arquivo historico Ultramarino de Bélem, from the former governor of Angola, Salvador Correia de Sá e Benavides (1648–1651), states that Philipe Hari I was Queen Njinga’s uncle; we know for certain that they were relatives.Footnote 60 Her brother, King Ngola Mbandi, died in mysterious circumstances, and writings from that time suggest that Queen Njinga killed him in order to take over the throne of Ndongo and rule the Mbundu people. However, after Philipe Hari I was elected king of Ndongo with the aid of the Portuguese on 12 October 1626, Njinga’s rule was confined to Matamba, east of Ndongo. Philipe Hari I and Njinga ruled for thirty-eight and thirty-nine years, respectively.

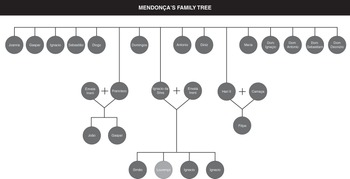

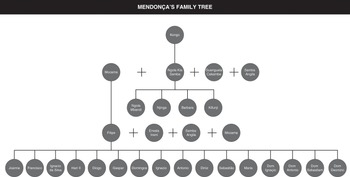

Mendonça’s family tree (see Figure 2 and Figure 3)Footnote 61 demonstrates that he was descended from the kings of Kongo who ruled over what is today known as West Central Africa and were the first royals to adopt Christianity in the region. Afonso I (1509–1543),Footnote 62 the king of Kongo, is said to have been related to Mendonça’s great-grandfather, Ngola Kiluanji Kia Samba (1515–1556), king of Ndongo and Matamba.Footnote 63 It was not a far-fetched statement, therefore, when Mendonça made the claim in the Vatican that he was descended from the ‘royal blood of the kings of Kongo and Angola’.Footnote 64

Figure 2 Lourenço da Silva Mendonça’s family tree, part 1. By the author, based on manuscripts.

Given Mendonça’s origins in Kongo and Angola, Africans were demonstrably the prime campaigners for the abolition of African enslavement in the seventeenth century. In presenting his court case in the Vatican about the plight of enslaved Africans in Africa and in the Atlantic, and the oppression of Natives and New Christians in Portugal,Footnote 65 he put forward a universal message of freedom – all these groups included people whose humanity was being denied. This challenges the accepted view that ‘the conduct of the slave-trade involved the active participation of the African chiefs’.Footnote 66 There were, indeed, many within Africa who refused to accept and actively opposed the Atlantic slave trade, and who abhorred its ideology and practice. Mendonça represented those constituencies from his own family – his grandfather, Philipe Hari I, and father, Ignaçio da Silva – who were coerced into the slave trade by the Portuguese regime in Angola.Footnote 67

In my view, and in accordance with the documentary sources used in this book, it was unquestionably Ignacio da Silva’s son Lourenço who went to Rome to present the case for abolition there on 6 March 1684; he took his father’s surname to become Lourenço da Silva e Mendonça, or, in some documents, Lourenço da Silva de Mendonça.Footnote 68 It is possible that Lourenço may have been given the surname Mendonça by the governor of Bahia, Afonso Furtado de Castro do Rio de Mendonça, with whom the Angolan royals stayed for sixteenth months of their stay in Salvador.Footnote 69 The uncertainty about Lourenço’s surname stems from the fact that only his first name appears in the original documents in the Portuguese archives.Footnote 70 In fact, only the first names of his brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins were recorded.Footnote 71 There is a second possibility in that he could have used the surname Mendonça at home, in Ndongo, as this was not unusual. Mendonça’s uncle, a Portuguese captain, António Teixeira de Mendonça, who had lived with his aunt (Philipe Hari I’s daughter) for more than 10 years, also had the same surname.Footnote 72 It would not be far-fetched to suggest that Mendonça was so named in his honour.Footnote 73 He may have also received the surname Mendonça, if António Teixeira de Mendonça was his godfather, at his baptism. Such was the case with Mendonça’s grandfather, Ngola Aiidi, who was given the name Dom Philipe de Sousa when he was baptised in Luanda on 29 June 1627 in honour of Dom Philipe III of Portugal and Philipe II of Spain, and Sousa in honour of his godfather, Fernão de Sousa, the governor of Angola.Footnote 74

As mentioned, towards the end of 1671, after the war of Pungo-Andongo,Footnote 75 Mendonça, his brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins were sent to Salvador, Bahia, by the governor of Luanda, Francisco de Távora ‘Cajanda’ (1669–1676); they lived there for eighteen months.Footnote 76 In 1673, Mendonça was then taken to Rio de Janeiro, where he lived for, possibly, six months.Footnote 77 After spending two years in Brazil, he was sent to Portugal in August 1673. In Portugal, he stayed at the Convent of Vilar de Frades, Braga, by order of the Portuguese Crown. His three brothers were sent to Braga, too, but to different monasteries: Basto, Moreira and Selzedas.Footnote 78 Mendonça probably studied law and theology in Braga for three or four years, from 1673 to 1676 or 1677, before returning to Lisbon, where he stayed for perhaps four years from 1677 to 1681.Footnote 79 The exact details of Mendonça’s life over the next five years are unclear, though a few details are discernible from a recommendation letter that he carried with him from the apostolic notary in Lisbon, Gaspar da Costa de Mesquita. In 1682 he departed for Madrid.

It is intriguing that the family name Mendonça [Mendoza], according to Lope de Barrientos, was a Jewish surname.Footnote 80 The aristocratic Mendoza family ‘originated from the town of Mendoza in the province of Álava in the Basque countries’ in Spain. The Mendoza family in Spain wielded considerable power and influence when Álava joined the kingdom of Castile during the reign of Alfonso XI (1312–1350). The surname’s history might not have any direct bearing on Mendonça’s own name, nor on his alliance with Jewish descendants, the New Christians, in Portugal. Nonetheless, it is significant for my argument in this book as far as Mendonça’s dialogue with and the support he gained from Gaspar da Costa de Mesquita, the apostolic notary in Lisbon, in the 1680s is concerned. The Mendonça name is suggestive, as there might be a link to the New Christians in Angola. There is, indeed, evidence that New Christians in the Kongo, Angola and Cacheu [in modern Guinea-Bissau] were marrying into the ruling class and forming alliances in order to gain political influence and protection in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 81 Some of the New Christians helped the African kings with intelligence information on Luso-Hispanic operations in Africa. The Crown in Madrid was very unhappy with this situation and accused the Vatican of turning a blind eye to what was happening. This may sound trivial to Mendonça’s family and personal history, but it is important to his case as it demonstrates the existence of a ready-forged network between the New Christians and the élite classes in West Central Africa, to whom Mendonça belonged.Footnote 82 A royal letter from Madrid, dated 28 August 1618, stated that:

The complaints from the King of Kongo are fostered by some restless people from the Hebrew NationFootnote 83 who, out of fear of the Inquisition Tribunal, left Portugal and now live in that part of the world. For that, they see themselves as having a place with the King. They helped him with writing letters and provided him with intelligences together with others from the same Hebrew Nation that reside in this Curia.Footnote 84

The conviviality that existed between the New Christians and the Africans in West Central Africa and in West Africa moved beyond inter-group solidarity to infiltrate the highest-level institutions such as the Curia Vaticana. It would not be far-fetched to assume that Mendonça tapped into this existing network.

The letter of recommendation that Mendonça carried with him from Lisbon to the Vatican, dated 15 February 1681, raises questions over Mendonça’s racial heritage. In the letter, Mendonça was described as a homen pardo. This translates in Italian as morrate, which in Spanish could have been translated as moreno – that is, a dual-heritage person;Footnote 85 Richard Gray translates it as ‘mulatto’.Footnote 86 However, according to Hebe Mattos, the term ‘pardo’ in the seventeenth century could mean both ‘Black’ and ‘mulatto’.Footnote 87 In seventeenth-century Spanish America, the term pardo could mean someone who is born free,Footnote 88 and I favour this latter meaning, ‘born free’, when referring to Mendonça’s identity. Mixed marriages in seventeenth-century Angola were not unusual, and King Philipe Hari I could well have married dual-heritage or Portuguese women. The Portuguese Crown decreed in the sixteenth century that any allied African king’s daughter should marry within the Portuguese royal family, or, if there were no royal heir, marry into the Portuguese nobility. In the sixteenth century, the king of Caio (in modern Guinea-Bissau) travelled to Cape Verde with his nobility, and declared that his daughter, who was of marriageable age, was expected to marry Portuguese nobility. When he arrived in Cape Verde, he sent a message to the Portuguese Crown that a marriage to his daughter should be contracted.Footnote 89 Among the Peniche group (the brothers of Mendonça who were not sent to Brazil with him, but who instead were despatched directly to Portugal and on to Peniche town) was ‘Francisco the Black’, which indicates that Mendonça and his relatives may have been of dual heritage. Francisco was the servant (‘free’ servant or subordinated rank and not a chattel enslaved person)Footnote 90 of Ignacio, the illegitimate son of King Philipe Hari I.Footnote 91 The Portuguese decree could be viewed as contradicting the purity of blood doctrine that was sacrosanct at the time. However, more research is needed in order to come to a definitive conclusion here.

Ultimately, there may have been many Lourenço da Silva Mendonças in Angola, Kongo or Brazil. However, according to our documentary sources, few would have been princes and had a bloodline going back to the kings of Kongo and Angola, as Mendonça’s did. Situating Mendonça in his political landscape in West Central Africa is pivotal to our understanding of his court case, since only in this way can we rethink the historiography of Atlantic slavery with regard to so-called African slavery.

0.2 Studies and Sources for Mendonça’s Work and Historical Context

Richard Gray was the first historian to bring Mendonça’s work in the Vatican into the public domain. In his pioneering article, ‘The Papacy and the Atlantic Slave Trade: Lourenço da Silva, the Capuchins and the Decisions of the Holy Office’, Gray argues that Mendonça’s presentation in the Vatican was a petition in which he appealed to the Holy Office to deal with the suffering of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic.Footnote 92 In Gray’s view, Mendonça did not argue for the universal condemnation of slavery, but rather for the liberation of enslaved African Christians and their offspring. Gray’s findings centred on the Vatican archives and did not include data on Mendonça from Spain, Portugal and Brazil. He was well aware of this limitation and, in fact, kindly recommended that I carry out research in those countries’ archives.Footnote 93

In an attempt to widen the scope of Gray’s research into the Black Atlantic, a Brazilian historian, Hebe Mattos, has published a comparative study on Mendonça and Dias entitled ‘“Pretos” and “Pardos” between the Cross and the Sword: Racial Categories in Seventeenth Century Brazil’.Footnote 94 Her main interest is to look at categories of pretos (Blacks) and pardos (mulattos or free people), and their emergence in Brazil. She argues that ‘the two cases presented here appear to suggest a more central role for the early demographic impact of access to manumission in colonial society and the possibilities for social mobility among the free peoples of African descent’.Footnote 95 Mattos employs these categories to unpick the roles played by both Henrique Dias, governor of Crioulos and commander of the Terço da Gente Preta,Footnote 96 in Brazil in the mid-seventeenth century, and Lourenço da Silva Mendonça, a procurator general from the confraternities of Black Brotherhood. However, Mattos does not include Mendonça’s network in Brazil in her study, nor explore his connection with Indigenous Brazilians. Most importantly, Mendonça’s Vatican court case does not feature at all in her work. She acknowledges Gray’s research but does not detect that Mendonça’s intervention is a court case nor that his abolition message was for all Africans, across the Atlantic region – and not only in Brazil but in the entire Aermican continent; nor does she recognise his interconnection with Black confraternities in Portuguese America, Brazil and Spain. This was not through lack of interest, but simply because of a lack of data to support a more in-depth analysis of the debate about the abolition of slavery in the Atlantic in the seventeenth century. Gray and Mattos are the only two contemporary scholars to have focused on Mendonça.

When it comes to historical sources, in 1682 the Jesuit missionaries Francisco José de Jaca and Epifanio de Moirans, who knew and supported Mendonça’s court case, completed their work Servi Liberi Seu Naturalis Mancipiorum Libertatis Iusta Defensio (Freed Slaves or the Just Defence of the Natural Freedom of the Emancipated).Footnote 97 Both also offered a critique of the capture of Africans in Africa who were then taken to the Americas as enslaved people. While renowned Spanish Jesuit Bartolomé De las Casas (1484–1566)Footnote 98 defended the Indigenous Americans against slavery, the lesser-known Jaca and Moirans also spoke out against the enslavement of Africans using the legal arguments of the time. Their work, however, did not come to the fore in the debate on the Atlantic slave trade until the beginning of the 1980s, when their defence was translated from Latin to Spanish by José Tomas López García as Dos Defensores de los Esclavos Negros en el Siglo XVII (Two Defenders of the Black Slaves in the Seventeenth Century). Neither Jaca nor Moirans went to Africa as missionaries, but they both worked as Jesuit priests in Venezuela and Cuba, where they met. Their defence is a major work on the injustice of African enslavement in the Americas, and on the abolition of slavery in the Atlantic, yet it is almost unknown. They analysed in great depth the same legal terms that were used by Mendonça in the Vatican, such as ‘natural’, ‘human’, ‘divine’, ‘civil’ and ‘canon law (jus canonico)’, challenging why Atlantic slavery was being practised against these laws.Footnote 99 They argued that the Atlantic slave trade was illegal, stating that ‘when we begin with natural law, all men are born free’.Footnote 100 They contended that the responsibility for those enslaved Africans in the Americas lay with the pope, because ‘the lords of blind slaves with their ambition to impress the Governor (the governors in the Indies are subject to the Catholic King and the kings are subject to the Pope)’.Footnote 101 This chain of responsibility made it necessary for the pope to punish the guilty parties committing such crimes, particularly the Portuguese governing authorities in Africa, Brazil and the Americas. And this obligation also implicated the pope in a crime against humanity: the Atlantic slave trade. Indeed, Jaca and Moirans stood in the witness box in the Vatican to testify on behalf of Mendonça’s court case, arguing that each ‘person is free by natural law’.Footnote 102

In their thesis, Jaca and Moirans also asked uncomfortable questions as to why Christians bought enslaved Africans, who were captured using force, fraud, intimidation, kidnapping and theft. They argued that the transaction carried out and the value of the things exchanged for human beings were worthless in comparison to the human beings bought. For them, such exchanges should never have taken place. They asked:

Would Christians like this to be done on their lands and in their regions? Would they like to be made slaves and be bought? Would they like to be captured with violence and fraud and tied up and transported? How can they commit such lawless things and how could they harden their hearts to the evil, the force of sins against natural, positive, and divine laws?Footnote 103

They used their knowledge of the Americas and their experience with enslaved Africans to strongly support Mendonça in the Vatican. Furthermore, they openly criticised the Atlantic slave trade and demanded that the enslaved Africans’ owners pay back what they owed the enslaved for their work and release them from bondage.Footnote 104 For them, as for Mendonça, natural, human, divine and civil laws were universal, and had been broken by the enslavement of Africans.

Dating from the same time, the three-volume history of the Angolan wars completed by Antonio de Oliveira Cadornega in 1681 is fundamental to understanding the socio-political and cultural circumstances surrounding Mendonça’s court case, the context of the Portuguese conquest and the wars waged on the Ndongo kingdom.Footnote 105 Cardonega came to Angola with Governor Pedro Cesar de Menezes in 1639, serving in the military. He initially became a captain, but then followed a civil and subsequently political career, becoming ordinary judge in 1660 and municipal councillor of the City Council in Luanda in 1671. Not only does he give details on the wars, but he also offers ethnographic and geographic insights into the period.

Two and a half centuries later, in 1944, Father António Brásio, a Portuguese priest, missionary and historian, compiled his vast collection Monumenta Missionaria Africana, an account of the activities of Portuguese missionaries in Africa. The text covers the period from the arrival of the Portuguese in Africa in 1446 to 1700. While he included documents on Mendonça, he did not know of his role and does not mention Mendonça’s work in the Vatican at all. He also wrote a book, entitled Os Pretos em Portugal (Blacks in Portugal), about the freedom of enslaved Africans in Portugal.Footnote 106 He examined historical documents on the existence of Black Brotherhoods in Lisbon and described how some members had gained their freedom within the law using the rights conferred on them in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, this work does not extend much beyond Portugal, since the only mention of another Black Brotherhood in the Atlantic sphere is the confraternity of Massangano in Angola.Footnote 107 Brásio uses his work on Black Brotherhoods in Portugal to argue that the treatment of enslaved people in Portugal was not as brutal as many people might have been led to believe. Writing in the twentieth century, he used the freedom of the enslaved Africans in sixteenth-century Portugal to deny that Portuguese society was racist, using it as a defence against charges levelled at Portugal in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and at colonialism in general.Footnote 108 For Brásio, enslaved Africans in Portugal were treated humanely. He argues that the country had no equal in its civilising mission and race relations in any part of the world, and was – for that reason – superior to the United States of America.Footnote 109

French historian Didier Lahon, who has continued the work begun by Brásio on Black BrotherhoodsFootnote 110 in Portugal, is more aware of Mendonça but argues that his achievement with these confraternities was limited because of the social and political constraints of the time.Footnote 111 Brásio and Lahon stand for one of two key arguments used to sanitise slavery and colonialism: firstly, that they were part of a greater civilizing mission and secondly, that slavery was already in existence and widely practised by Africans in Africa. For Lahon, the presence of African confraternities in Portugal somehow diluted and contradicted Portugal’s ideology as an enslaving society. However, the author does not recognise the African agency and fight for freedom through the Black Brotherhoods because he does not conceive of them as possible in this historical moment.

Like Lahon, Brazilian scholar Lucilene Reginaldo, who works on Brazilian and Angolan Black Brotherhoods and the circulation of Black men in the Atlantic world,Footnote 112 does not engage with Mendonça’s work. However, her work is important in understanding confraternities of Black Brotherhood in Brazil, particularly in Salvador, Bahia, where Mendonça received great support for his court case in the Vatican.Footnote 113 For Reginaldo, Black confraternities in Bahia were Africanised through practices they brought from Kongo and Angola.Footnote 114 They preserved their tradition with the memory of the king of Kongo. According to Reginaldo ‘the King of Kongo represented the triumph of continued strategies to preserve links with Africa’.Footnote 115 She argues that the Angolans were the first to form brotherhoods in Bahia. They used them as a space in which to overcome their daily challenges and as a legal support for themselves.Footnote 116 For Reginaldo, confraternities were ‘channel[s] of expression and integration of the Black people in the colonial period’.Footnote 117 She pointed out that Angolans made up the great majority of Bahian confraternity members and dominated the groups’ leadership.

With regard to the question of slavery in Africa, in the nineteenth century Pedro de Carvalho, Portuguese secretary to the governor in Angola between 1862 and 1863, stated in his book Das Origens da Escravidão Moderna em Portugal (Origins of Modern Slavery in Portugal), that ‘Africa is a land of slavery by definition. Black is a slave by birth.’Footnote 118 Contrary to the lone voice of Portuguese priest Father Oliveira, who in Elementos Para a História do Município de LisboaFootnote 119 criticised Portugal as an enslaving society by seeing it as the only country responsible for Atlantic slavery, Carvalho argued that ‘we [the Portuguese] did not invent Negroes’ slavery; we have found it there, which was the foundation of those imperfect societies’.Footnote 120 Other Portuguese historians have also defended Portugal’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade by echoing sentiments expressed by both Carvalho and Brásio.Footnote 121 Among them is the nineteenth-century writer and patriarch of Lisbon, Father Francisco de S. Luís. In Nota Sobre a Origem da Escravidão e Tráfico dos Negros (Reflection on the Origin of the Slavery and the Traffic of Enslaved Black Africans) – an answer to French authors Christophe de Koch and Frédéric Schoell, who had accused Portugal of being responsible for the slave tradeFootnote 122 – Luís contributed to the invention of the seductive and misleading narrative that Arabs and Africans were already trading in enslaved people in Africa before Portugal became involved in the Atlantic slave trade. This has become the dominant version of the history of slavery in the region and is intended above all to shift responsibility and guilt from Europeans to Africans.Footnote 123

The historiography of West Central Africa initially focused on itaFootnote 124 – ‘war’ – as an enslavement method. Historians working with this focus have included John Thornton, David Birmingham, Beatrix Heintz, José C. Curto and Mariana P. Candido;Footnote 125 others such as James Walvin, Paul E. Lovejoy and Patrick Manning have focused on ita but for Africa as a whole rather than West Central Africa.Footnote 126 Away from the focus on ‘war’,Footnote 127 historians have paid particular attention to xicacos (tributes of vassalship) – or ‘taxation’.Footnote 128 Both Beatrix Heintze and Mariana P. Candido have considered these two elements together and engaged with the significance of the fact that ‘raiding’ and ‘taxation’ were important as a source of income to cover the Portuguese administration’s expenditure in seventeenth-century Angola. Subsequently, the focus on ‘war’, ‘raiding’ and ‘taxation’ has given way to an emphasis on ‘debt’. Historians such as Joseph Miller, Jan Vansina, José Curto and Roquinaldo FerreiraFootnote 129 have used this as a focus in their analysis of the ways in which Africans were enslaved in West Central Africa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Alongside ‘debt’, historians have also examined ‘judicial proceedings’Footnote 130 – the tribunal de mucanos (mucanos tribunal). A tribunal of mucanos means ‘legal verbal proceedings in their disputes and demands’ in the Angolan language Kimbundu.Footnote 131 Mucanos were local courts, indigenous to West Central Africa, used to deal with legal cases. The above-mentioned historians have used these local legal structures to argue that the enslavement of Angolans was part of the West Central Africans’ culture, and that enslavement was used as a punishment for those found guilty of breaking the law. Ferreira argues that civil and criminal cases were used by sobas to enslave the guilty in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 132 He challenges West Central African historiography that views enslaved Africans in the region as war captives and calls for its revision, deploying individual cases to reveal that enslavement was carried out through acts of kidnapping and betrayal. In a similar vein, Candido has demonstrated that in Benguela the Portuguese governing authorities were not only waging war as a method of capturing Angolans but also using debt and judicial practices to enslave them.Footnote 133 Similarly, Joseph Calder Miller in his work Way of Death has argued that the Portuguese used the judicial system to obtain enslaved Africans in the region by enforcing debt recovery as a method in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For Miller, the enslavement of Angolans was carried out in regions far away from areas of Portuguese settlement.Footnote 134 Alongside historiography on ita, Curto has demonstrated the problem of social conflict that was created by the slave trade in which people were ‘kidnapping’ others in revenge for enslaving their family members, particularly the slave-traders in the region. This social conflict was actually driven by the need to pay debt.Footnote 135 Recently Daniel B. Domingues da Silva has endorsed the claim, made by both Candido and Ferreira, that the Portuguese-enslaved captives sent to Brazil from Angola came from the region controlled by the Portuguese, rather than from a distant territory, as Miller’s work showed.Footnote 136

Intriguingly, the idea of the legal system being used to capture and enslave Angolans, which has dominated the recent historiography of West Central Africa, is not new. It stemmed from the earlier seventeenth century, with the introduction of baculamento as a form of payment of taxes in enslaved people. Raiding in the region controlled by the Portuguese is not new, either. An example of this is Correia de Sousa capturing Kazanze and Bumbi people. No historian has identified the true importance of the introduction of baculamento, which became the basis of the ensuing system of enslavement in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Mendonça’s argument in the Vatican in 1684 pieced together these themes, which later became the subject of debate in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the historiography of West Central Africa. These were already subjects discussed among the confraternities of Black people in Brazil, Portugal and Spain in the seventeenth century.Footnote 137 None of the historiography mentioned above made this connection.

Just as the historiography of West Central Africa has focused mainly on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so the debate on the abolition of slavery in the region has concentrated on the same period – as if abolition were not a theme of the seventeenth century. What is more, the abolition of Atlantic slavery is understood to have been an almost exclusively European endeavour, in which the fundamental part played by Africans remains in the background. Within Western scholarship, the Africans’ contributions to the debate on the abolition of the Atlantic slavery in particular and to world history in general have been, and continue to be, neglected. This led Michael Gomez, in his recent work African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa,Footnote 138 to question why so little attention has been paid to their role in shaping history. He states that even when historians have worked in fields in which the impact of Africans was obvious, their contribution has been brushed aside: ‘world history as well as the imperial annals require substantial preparation and endeavour, often an impressive, invaluable feat of erudition. It is therefore all the more disappointing that Africa continues to receive such short shrift.’Footnote 139 Toby Green endorsed this view in his work A Fistful of Shells, stating that ‘the modern world emerged from a mixed cultural framework in which many different peoples from West Africa and West Central Africa played a significant part. Yet, knowledge of these studies remains thinly spread.’Footnote 140

The sense of guilt among the continents involved in the slave trade – Asia, Europe and Africa – has often eclipsed the debate to the extent that the evidence-backed argument that Africans made a valuable contribution to abolition tends to provoke the response that both Africans and Europeans were active and willing participants in the slave trade. It has become almost anathema to make the point that the Africans were under significant pressure from their European allies to deal in enslaved people. The seventeenth-century Angolan form of offering service to their fellow human beings, known as mobuka (which can be translated from Kimbundu as ‘at your service’)Footnote 141 was grossly misinterpreted by European settlers and missionaries alike as a form of slavery.Footnote 142 For Angolans, mobuka did not categorise a person as a ‘slave’ in the European understanding of the word, and Africans never had interpreted the labour they offered each other in that way. Those offering mobuka were nonetheless branded by the Europeans as ‘enslaved people’ and sold into the Americas. The correlation between mobuka and slavery only emerged in the context of Atlantic slavery, and was, in the words of Suzanne Miers and Igor Koptyogg, an ‘unusual historical creation’.Footnote 143 Mendonça included criticism of this cross-cultural misrepresentation in his court case. What was meant exactly by the word ‘slave’ or ‘slavery’ and the practice of slavery in Europe and how these concepts were transferred to Africa and applied there contributed to significant misunderstanding. Accordingly, the complexities of African practice, and how both cultures approached the reality of service being offered and the general penal system in West Central Africa, have been misread.Footnote 144 As Gray remarks, ‘indeed those African peoples who were by the late-seventeenth century exposed to the Atlantic slave trade accepted within their own various degrees of servitude. Yet seldom, if ever, was the slavery in African societies rigidly perpetuated over the generations.’Footnote 145

The case studies of the people of Ndongo and Kazanze examined in this book engage with studies by Africanists, West Central African historians and authors who work on the African diaspora such as Birmingham, Linda M. Heywood, Heintze and Thornton, among others, but, above all with new historical sources that go beyond those from Cardonega and Brásio and that I encountered in many different archives.Footnote 146 These datasets show that Africans were coerced into slave-trading, particularly through the introduction of baculamento in Angola by the Portuguese governor, Fernão de Sousa, in the seventeenth century. Certainly, some of the African ruling class in different areas of Africa who were conquered were also coerced into the slave trade, including Mendonça’s grandfather, Philipe Hari I, and even his own father, Ignaçio da Silva. While their involvement could easily be generalised as normative, a product of its time, there exists no data to substantiate such a claim. The practice of baculamento could be seen as evidence for African collusion with slavery,Footnote 147 but in order to repudiate this interpretation I set out to examine original archival sources rather than rely on the same old secondary sources.

If we are to understand the different legal practices of coloniser and colonised in the Atlantic with reference to Mendonça’s court case, Lauren Benton’s discussion of the dialogical nature of this exchange in Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History is very useful. She writes about the intersection of legal regimes from the Western and non-Western worlds in the process of colonial formation in Africa, Asia and the Americas, and argues that local social history played a fundamental role in shaping Western legal theory in the contact zones, where there were ‘conscious efforts to retain elements of existing institutions and limit legal change as a way of sustaining social order’.Footnote 148 Western legal jurisprudence was transformed as it entered into dialogue with local legal systems that were already operating in these regions before the Europeans came there. What emerged from this encounter is what she terms ‘global legal regimes’.Footnote 149 However, Benton pays less attention to the familiar legal and international law applied by both Africans and Europeans in disputes about ending the Atlantic slave trade. In the seventeenth century, the Supreme Court of Christendom in the Vatican was used to arbitrate on abuses of Africans and Indigenous Americans in the Americas.Footnote 150 My argument in this book is that Mendonça used the Supreme Court, bypassing local courts, such as the Angolan, Kongolese, Brazilian, Portuguese and Spanish courts. Instead, he went to the Vatican to present his legal case against Atlantic slavery.Footnote 151

What is more, his criminal court case went beyond the denunciation of the enslavement of Africans. Proposing the concept of the ‘Black Atlantic abolition movement’ is an attempt not only to make sense of the philosophy underlying Mendonça’s case in the regional setting from which it developed but also to align it with other compatible themes in the Atlantic world of the Americas and Europe. The alignment of Africans with other Africans that began in West Central Africa, in which Kongolese and Angolans allied with each other, helped them to unite with wider constituencies of those whose freedom was being denied in the Atlantic, such as the New Christians.Footnote 152 However, Mendonça’s exile to Brazil and Europe provided him with the impetus to act and solidarity with those who were on the receiving end of global Atlantic injustice: enslaved Africans in the Americas, Indigenous Americans and New Christians. Applying the concept of a Black Atlantic abolition movement is to engage with the Atlantic as a political and legal space, and to engage with the nexus of dialogue and interactions between its different constituencies, which have not so far been included together in the Atlantic debate. This is a more nuanced understanding than seeing it, as Paul Gilroy does, as a space of cultural meaning and ‘historical production’.Footnote 153 I use the idea of a Black Atlantic abolition movement to move away from the notion of the ‘Black diaspora of the Atlantic’, which is understood to only include Black Americans, British and West Indians. The concept of the ‘Black diaspora of the Atlantic’ does not embrace other oppressed constituencies, such as Indigenous Americans and the New Christians who circulated in the Atlantic and in the metropolitan centres of Europe (Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands), along with white descendants of enslaved people in the Americas.Footnote 154

Accordingly, I understand the Black Atlantic abolition movement as a project of solidarity and a common search for freedom. The relationship that was formed between whites, Africans, New Christians and Indigenous Americans emerged from a shared desire for and working towards liberty that was articulated in Mendonça’s court case as a discourse to defend this position.Footnote 155 I use ‘discourse’ to refer to his speech in the Vatican as a form of utterance, but also in its Foucauldian sense,Footnote 156 to indicate how language and practice (institution) regulate ways of speaking that in turn define, construct and produce objects of knowledge, because knowing what counts as regulated truth involves relations of power and knowledge.Footnote 157 Mendonça presented his court case as utterance, but also as discourse in his attempt to refute the merchants and governing authorities in Brazil, Africa and the Iberian Peninsula’s version of discourse on Atlantic slavery.Footnote 158

Mendonça’s court case cannot be discussed outside the wider context of his royal background, West Central African history and how the Portuguese project of conquest shaped it. This brings us back to the problem of historical sources. Although there is some debate concerning the origin of the kingdom of Ndongo, I will not address it in detail here.Footnote 159 Suffice to say, records of the myths of origin of African kingdoms written down in the early period of the European encounter with West Central Africa in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries do not convey their full meaning.Footnote 160 Myths of origin of African kingdoms and places lie at the intersection of political, cultural, religious and economic power, and they need to be understood from these multifaceted perspectives.Footnote 161 In an attempt to engage with the history of Ndongo from the seventeenth century, one is clearly dependent on accounts written by missionaries, administrators, soldiers, travellers and overseas envoys. Most of these were Portuguese, with a handful coming from Italy, Spain and the Netherlands.Footnote 162 All, however, had an overtly Christian civilising mission and a political agenda that aimed to exploit the African subjects of their writings and to condone the taxation of Africans and the existence of African slavery.Footnote 163 In other words, their writings were not apolitical – as can be perceived in the historical documents themselves; and, as post-colonial scholars and historians have pointed out, their own positionality was determined by a distinct identity framed within the context of time and space and within the social settings and power relations of the period.Footnote 164 Heintze and Katja Rieck have warned us about the problems of dealing with written sources on Ndongo’s history, in that, ‘most texts … often were written by eyewitnesses, or at least by contemporaries, but they were written to serve Portuguese assessments, decisions and actions’.Footnote 165 It is this positionality, ‘the who, where, when and why of speaking, judgement and comprehension’,Footnote 166 that constrained their thought.Footnote 167 This is not to suggest that sources written by Africans themselves would have been free from ideological overtones. However, sources collected and written by Europeans, whether Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch or Italian, are not to be considered as original, unbiased sources in themselves; nor are they to be used as the yardstick for the interpretation of oral African histories.Footnote 168 Most of these sources were oral in their circulation long before the Portuguese wrote them down, and it is imperative that African perspectives and voices are included in the writing and interpretation of African history.Footnote 169 European sources have long been considered authoritative, despite the political conditioning of their authors, while African voices, even those documented within European sources, have remained in the background. What I am advocating is that a cautious and balanced reading of these sources must be conducted if we are to give voice to both Europeans and Africans of the time.Footnote 170 The historical sources of Mendonça’s court case are probably the most outstanding examples of this. Let me explain where I found them and of what they consist.

When I began my research I thought, as Gray had always maintained, that the case Mendonça took to the Vatican was a petition to obtain the abolition of African slavery. However, the documents I discovered in Arquivo de Torre do Tombo (Archive of de Torre do Tombo), Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (Overseas Historical Archive in Belem, Brazil), the Archivo del Palacio Real (Archive of the Palace in Madrid, Spain) and the Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Archive of Propaganda Fide, Vatican) forced me to abandon my assumptions. Mendonça’s case was not a petition, but a fully fledged criminal court case: ‘Lourenço de Silva, arrived in Rome several times to report the complaints, the appeals of the poor Blacks enslaved and the burdens they receive in those parts.’Footnote 171 His liberation discourse was not just directed at African slavery, but was a universal message of freedom for all those, including Indigenous Americans, Brazilians and the New Christians in the Americas, Spain and Portugal, who were not members of the ‘Jewish race nor pagans, but only following the Catholic faith, akin to any Christian, as is known’Footnote 172 – on the receiving end of injustice in the Atlantic region.

By 1686, two years after the Vatican adjourned Mendonça’s court case, confraternities of Black Brotherhoods from across Brazil and the Americas had organised themselves to send a memorandum of grievance to the Vatican, which was taken there by Paschoal Dias, a freed Angolan enslaved in Salvador (then the capital of Brazil).Footnote 173 The confraternities declared that ‘their miserable condition’ was being overlooked. They claimed the daily deaths of enslaved people were being ignored by the Supreme Court of Christendom, even though they were members of the Universal Church. And they sought to ‘inform the Pope of the miserable state in which all the Black Christians of this city and all the other cities of this Kingdom of America are’.Footnote 174 The aim of the Salvador memorandum was to confirm in the strongest terms the brutality and ill treatment suffered by the enslaved African Christians in Brazil.Footnote 175 Six confraternities from the city of Salvador – Our Lady of Rosary of Desterro, Our Lady of Rosary of Black Men from São Pedro, Our Lady of Rosary of Conceição, two confraternities from São Benedicto and Our Lady of Rosary from the Main CathedralFootnote 176 – led the complaint and demanded a review of the case in the light of their evidence. The memorandum from Brazil was approved by the bishop of Brazil, Dom João, and his judge’s scribe, Francisco da Fonsequa [Fonseca].Footnote 177 Fonseca was the scribe of the ‘Cathedral of the City of Salvador, Bahia and of the kingdom of Brazil in the Americas. He was in charge of the Public Office and other roles in the City. He was nominated by order of His Highness.’Footnote 178 He gave Paschoal Dias the authority to carry the evidence in memorandum to the Vatican on 2 July 1686.Footnote 179 The memorandum was a universal condemnation of slavery, made with the aim of abolishing slavery.Footnote 180 Mendonça and the confraternities of Black Brotherhood included a case in the Vatican from the Caribbean islands as they sought to find the best solution to ways in which they were being treated and to gain freedom for enslaved Africans in Brazil and elsewhere. They appealed for the indentured servants’ law of the French Constitution to be applied in the New World to alleviate the death toll among enslaved people in the Atlantic. The French indentured servants’ law known as engagés or trente-six mois (thirty-six months), was passed on by Act of Parliament in 1663, and this allowed poor French emigrant citizens to move to the French Caribbean and work for three years for a French slave-master. After this period of service, then they would be set free.Footnote 181 Based on this evidence, I will argue that Mendonça’s criminal court case was a universal condemnation of the Atlantic slave trade. It provided a global voice against the Atlantic slave trade, which was an attack on humanity itself. Atlantic slavery was undermined the human values of natural, human, divine and civil laws, he argued. What distinguishes us from animals was reversed in the Americas: human beings were treated as animals, whilst animals were treated better than human beings.Footnote 182 Some slave-owners had, in fact, descended to a level in which it did not matter how humans were treated.Footnote 183

Mendonça’s court case began on 6 March 1684 and lasted for two years.Footnote 184 Mendonça travelled numerous times to the Vatican to make his case.Footnote 185 Louise Kallestrup states that, in Roman legal procedures, ‘more complicated trials were held in close communication with the Holy Office’.Footnote 186 Mendonça demanded the intervention of the Holy Office so ‘that Your Holiness will deign to give this subject back to the Holy Congregation of the Holy Office and to the one or Propaganda Fide’.Footnote 187 The Vatican’s response was that the people involved in buying and selling enslaved Africans, particularly those found committing crimes against Christians, should be punished, and the Vatican put huge pressure on Spain and Portugal to stop such cruelty to enslaved Christians in Africa and in the Atlantic.Footnote 188 Both Carlos II of Spain and Pedro II of Portugal, whose reigns coincided with Mendonça’s court case, wanted to abolish Atlantic slavery, but they were prevented from doing so by advisors including the Council of Indies and the Portuguese Overseas Council.Footnote 189 The Portuguese Crown responded to the Vatican’s demand of 18 March 1684, made in response to Mendonça’s court case,Footnote 190 by improving conditions of shipment for enslaved Africans being taken from Angola and Cape Verde to Brazil.Footnote 191 The Portuguese Crown also pledged to punish governors or merchants found to have committed crimes against the enslaved in Brazil and elsewhere.Footnote 192

Mendonça began his reclamazioneFootnote 193 (see Figure 1) or court case in the Vatican not with African involvement in slavery, but rather with a bold statement of his argument and evidence about how the capture of Africans was implemented, and the methods that were deployed to enslave them.Footnote 194 In doing so, he refuted the established thinking that Africans were willing participants in the Atlantic slave trade, and the idea that there were existing markets in Africa for enslaved Africans.Footnote 195 Mendonça accused the Vatican, Italy, Portugal and Spain of crimes against humanity, claiming, ‘they use them [enslaved people] against human law’.Footnote 196 The legal concept of a ‘crime against humanity’ may not have been current at the time of Mendonça’s case, although it is implicit in both natural and human laws. However, the term is frequently used in the documents Mendonça presented in the Vatican, and Roman legal jurisprudence has influenced the European legal system since that time.Footnote 197 I believe that Mendonça’s use of the term ‘crime against humanity’ anticipated its use in modern times. Atlantic slavery, as he saw it, was an attack on the human values of freedom, liberty and free will. For him, slavery was indeed a crime against humanity according to four principles of law known to human societies: natural, human, divine and civil.Footnote 198

The documents for Mendonça’s court case in the Vatican were later organised into three categories, based on the order in which they were presented and their importance, using the letters (A), (B) and (C) (see Figure 4 and Table 1), which indicates how the documents were preserved. (A) referred to Mendonça’s presentation of the first case as an attorney (procurator). (B) relates to the defendants’ responses, that is, the responses from the political governing authorities in Italy, Spain and Portugal, and the slave-masters in Spain, Portugal and Brazil. Documents labelled (C) record the plaintiff’s cases and the voices of the Africans from different organisations, confraternities, including constituencies of ‘men’, ‘women’ and ‘young people’ within the confraternities themselves, and other interest groups.Footnote 199 Cases (A) and (C) are similar in content, although (C) reinforces (A). (B) responds to (A). The contents of (B) – the Spanish, Portuguese and Roman governing authorities’ responses – were met with huge protest from the Black Africans in Africa, Spain, Portugal and Brazil, and the pressure groups represented by (C). The ‘men’, ‘women’ and ‘young people’ of those Black confraternities sent their grievances to the pope, disapproving of what was said by the constituency of (B). Indeed, waves of protest were driven towards the Vatican: ‘after receiving his replies, the Blacks have complained again to this Congregation raising the same grievances and pleading to provide to their miserable condition as in the paper C’.Footnote 200

Table 1 The system of Mendonça’s court case documents, as filed in the Vatican. Photograph by the author

It is imperative to note that many court cases were brought by enslaved Africans against their masters and vice versa and by those subject to the Inquisition in the Atlantic in this period of the seventeenth century.Footnote 201 They were, however, presented as individual cases and, unlike Mendonça’s case, were not taken to the Supreme Court of Christendom, the Propaganda Fide or ‘General Congregation’ at the Vatican, which was charged with dealing with any issues arising overseas, including missionary work in Africa, Asia and the Americas.Footnote 202 The constitution issued to the Black African confraternities in 1526Footnote 203 gave enslaved Africans the legal right to seek their freedom as Christians within churches of which they were members.Footnote 204 The constitution also allowed them to elect their attorneys. Accordingly, Mendonça was elected as an international lawyer in Portugal in the 1680s, and at the Royal Court of Madrid, Toledo, on 23 September 1682 and therefore allowed to practise ‘throughout the whole of Christendom in any kingdom or dominion’ and ‘using the economic and political right which is conferred to him’.Footnote 205

After Mendonça presented his case in court, the Vatican requested eyewitnesses. The confraternities selected, ‘three priests who have been missionaries in those areas. Two of them were Spanish and one Portuguese’.Footnote 206 They gave evidence similar to Mendonça’s. Two of the eyewitnesses were the above-mentioned priests, Jaca and Moirans, who were both asked by the confraternities or Brotherhoods of Black Christians from Brazil, Portugal and Spain to stand as witnesses for Mendonça in the Vatican. The document relating to their testimony, classified in (C), declares, ‘Mons. Secretary says that to provide against such illegal contracts it was proposed by the zeal of some Capuchin missionaries to declare wrong and to forbid, under punishment … some propositions which were sent to the Saint Office, but it is not known which decision has been taken about them.’Footnote 207 Both men confirmed the atrocities suffered by enslaved Africans in the Atlantic.Footnote 208 Before standing in the witness box in the Vatican, Moirans had already completed a thesis on the defence of Africans from enslavement.Footnote 209 The inhumane treatment of enslaved people was widely known in Brazil, Portugal, Africa and Spain by the seventeenth century, but the merchants and the governing authorities in the Iberian Peninsula who had long dominated the trade had covered up its abuses. In fact, and as referenced, they promoted slavery throughout Europe as benign, and in the Atlantic as a triumph of Christian missionary activity.Footnote 210

Mendonça’s court case was also shaped by the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563. Among the issues dealt with at the Council of Trent were the doctrinal challenges presented by the Protestant Reformation and the renewal of the Roman Catholic Church in the face of Protestant expansion. These challenges coincided with the age of European expansion to Africa, the Americas and Brazil.Footnote 211 The Council of Trent thus provides the background to the politico-religious landscape Mendonça encountered in the Vatican. The need to recruit new members for the Catholic Church meant that one of the outcomes of the Council of Trent was the requirement for Catholic kingdoms – Spain, Italy and, in particular, Portugal, with its monopoly of Africa – to invest the revenue garnered overseas on the expansion of Christianity, provide Christian education and formal education of Indigenous people, including Africans, the Indigenous Brazilians and the Natives in India.Footnote 212 At the Vatican, Mendonça was calling for the revitalisation of the inclusive principles that emerged from the Council of Trent. His appointment in Portugal as a lawyer for Blacks in Brazil, Portugal and Spain was made on the understanding that he supported the principles of Trent, and his appointment as an international lawyer in Toledo reinforced that understanding. His letter of recommendation from the papal nuncio in Portugal explicitly stated that Mendonça was given the affidavit in the spirit of the Council of Trent.Footnote 213

0.3 Methodology and Use of Sources

The book deploys a microhistorical methodology, opening a window onto an exceptionally complex and important period of colonial interconnections in the seventeenth century through the personal life story of Mendonça and that of his royal family, namely his brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins. The book thus offers one of the earliest Black Atlantic microhistories and uncovers an extraordinary story of an abolition movement that included other oppressed constituencies such as New Christians and Indigenous Americans, shedding light on Africa, Europe and colonial America in a crucial period of world history. It deals with the objective strategy and operation, network and universal nature of Mendonça’s criminal court case and abolition discourse that he presented to the highest court of the Christian world: the Vatican.

It is the prime purpose of this book to reveal the inclusive processes at work in Mendonça’s case as a Black Atlantic abolition movement that embraced the African enslaved, New Christians and Indigenous Americans. His case forced me to ask some fundamental questions about slavery that have previously been given unsatisfactory and ideological answers and to which this book attempts to offer new and perhaps uncomfortable responses: Were the enslaved Africans in the Atlantic already enslaved? How were they obtained? Who was a slave? If slavery was a normative practice in Angola, why would the enslaved run away to gain their freedom? More daring responses to these questions require an understanding of the conceptual issues around slavery in West Central Africa as understood by the Africans themselves, and the clarification and revision of some of the stereotyped views held about African slavery.

Crucial to the book is the question of how far Mendonça provokes us to rethink our methodological approach to studying Atlantic slavery and the abolition movement. Moreover, the research asks how the debate that surrounds the work on Mendonça extends and challenges our understanding of the African diaspora in the Atlantic. To engage with the complexities of Mendonça’s criminal court case and the troublesome issues that he raised in the Vatican, such as kidnapping, wars waged on Africans, treachery and robbery, with his legal defence based on natural, human, divine and civil laws, and with his universal freedom message for all, offers us a new understanding of Africa’s and Africans’ denunciation of slavery as a crime against humanity.

I have found it necessary to employ a loosely chronological and regional approach. However, the book also adopts a thematic approach, since I believe that the complex issues involved cannot be dealt with adequately through a chronological perspective alone.

This study builds on my prior research on Portuguese merchants, which has made it possible for me to question established interpretations of slavery in West Central Africa and to engage critically with the stances taken by the Vatican, and Italian and Luso-Hispanic merchants, and the methods they used to defend Atlantic slavery.Footnote 214 To engage with Mendonça’s abolition discourse, I have relied for the most part on primry sources, as explained above. This is generally new material that has not so far been used by historians, and which I encountered in archival and library records, and in various languages: in Latin, Kimbundu (one of the Angolan languages), Portuguese, Italian and Spanish.

The book’s findings are based on more than fifteen years of research, undertaken in fourteen cities and in thirty-seven archives.Footnote 215 I have uncovered new data in a variety of archives from three continents (Africa, America and Europe) and six countries (Angola, Brazil, Portugal, Spain, Italy and the USA) and each document encountered offered new insights and connections. The sources I found in Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino de Belém (AHUB), Torre do Tombo, Lisbon; Arquivo Nacional de Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; and both the Arquivo Municipal and Público de Salvador, Brazil, link Mendonça and his relatives directly to Quilombo de Palmares, something not previously known. Archival material encountered in the Torre do Tombo connects Mendonça to a wider Atlantic network of New Christians (Jews) in Portugal and Brazil. Other material found in the El Archivo General de Palacio de Madrid and the Archivo General de Simancas, Valladolid, Spain, links Mendonça with a Native American network. I traced trajectories from Ndongo to Salvador, Bahia; from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro; and from Rio de Janeiro to Portugal and then researched Mendonça’s journey from Lisbon to the Royal Court of Madrid, Spain and from there to the Vatican. This led to my carrying out research in Archivo de Diociano de Toledo; Angola Museu de Antropologia; the Archives of Propaganda Fide; Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana; Archivum Secretum Vaticanum; and the Historical Archives of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, Italy.Footnote 216

Regarding published sources, I have used the aforementioned sixteen volumes of Father António Brásio’s collection, Monumenta Missionaria Africana, in which he has brought together and carefully transcribed an extensive number of documents from different archives in France, Portugal, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands. The volumes cover the period of Portuguese expansion from the mid-fifteenth to the end of the seventeenth century. As observed earlier, the vast majority of the documents are not commented upon by him, but he sometimes makes explicit the names and people associated with a particular place and role. As Brásio’s work was commissioned by the Vatican, it is dominated by records of missionary activity in Africa; but Brásio has also transcribed many documents of wider political and cultural interest.

In order to question the established ideas on slavery and its abolition in the seventeenth century, I thought it imperative to carry out research based on archival documents that are scattered around the world. The fact that Mendonça had to move across the Atlantic in order to try to change the African predicament suggested to me a way of developing a methodology that could do justice to his cause by following in his footsteps.

Let me now present the chapter breakdown to explain how I have structured the narrative that is the outcome of my research.

0.4 Chapter Breakdown

Chapter 1 deals with the Municipal Council of Luanda and the politics of the Portuguese governors in Angola in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Municipal Council of Luanda became the site of political intrigue, jealousy, deceit and mutiny; it was a political landscape in which the main drive was for economic gain, and the enslavement of Angolans was a key part of that package. The methods deployed to capture Angolans – through wars, pillage and treachery – formed the basis for Mendonça’s Vatican court case.

Chapter 2 introduces the Ndongo and focuses on its relationship to Kongo in terms of political and social structures. It looks at the election of Philipe Hari I to the throne of Pungo-Andongo. It examines his rivalry and family ties with Queen Njinga, and how the Portuguese used his election to foster their trade relationships in Angola by introducing the baculamento tax system. The chapter then explores the role of João Hari II (Dom João de Sousa), also known as Ngola Aiidi,Footnote 217 the son who succeeded Philipe Hari I, and the ideology of Francisco de Távora ‘Cajanda’, the Portuguese governor of Luanda at the time.Footnote 218 It investigates the destruction of Pungo-Andongo and the sending of the kingdom’s princes and princesses, Queen Njinga’s nephews and nieces, to Brazil. The chapter is concerned with exploring the political environment of Angola and the wider region as the backdrop to Mendonça’s debate on freedom and the integration of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic.