When companies go abroad and organize on a transnational level to become multinational enterprises (MNEs), they face different risks than they usually encounter at home.Footnote 1 Political risk includes a broad range of dangers resulting from policies and decisions by governments (protectionism, control of capital, confiscations and nationalizations, and war, for example), the likes of which MNEs confront in foreign markets. MNEs have to deal with these risks and adopt frameworks for political risk management to ensure their profitability and existence from a long-term perspective.Footnote 2

The literature on MNEs and political risk has developed dramatically over the last fifteen years. Some important studies have focused on the interwar years and World War II, emphasizing the shock of World War I, when MNEs saw the confiscation of their assets in enemy countries, and the way these firms implemented strategies to avoid losses should a new war or political difficulty arise.Footnote 3 The most common responses were organizational innovation and cloaking, which allowed MNEs to adapt pragmatically to a changing political environment.Footnote 4

Yet after World War II, the emerging new order grappled with threats in the rise of communism and nationalist policies in many recently independent states. Numerous governments of former colonies adopted policies that restricted the activities of foreign firms in order to ensure the independence of their respective countries, strengthen their control over their domestic economies, or implement new, socialism-inspired economic systems.Footnote 5 The 1960s and 1970s represent an important wave of expropriation of foreign enterprises in African and Asian countries.Footnote 6 MNEs had to cope with these policies and find ways to survive in their environments. The common view in international business and business history is that, despite many developing countries becoming independent and seeking better control over the activities of foreign MNEs, the balance of power favored multinationals. Geoffrey Jones argues that technology and management skills gave leverage to multinationals, while large domestic markets and natural resources were factors that gave more power to governments.Footnote 7 In many cases, MNEs were present in a newly independent country preindependence and sometimes experienced a change in position after the advent of the nationalist government, like the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company did in the 1950s.Footnote 8 Some scholars in the social sciences use the obsolescing bargaining model, developed by Raymond Vernon, to show the impact of the change of conditions between the time of market entry (when an MNE could bargain against the host government) and the emergence of new political risk (when the MNE lost its bargaining power).Footnote 9 However, other scholars in the postcolonial theory school argue that post–World War II independence transitions had a limited influence on the power of MNEs because of hybridity and the pursuit of neocolonialism, as the case of British oil companies in India after 1947 shows.Footnote 10 This position minimizes the idea of a new and growing political risk after World War II.

However, MNEs adopted a broad range of strategies to face political risk in emerging countries after 1945. The first and most extreme decision was to disinvest and leave the country altogether: for examples one can look to India after independence and China after the establishment of a communist government.Footnote 11 For MNEs that decided to maintain a presence in these markets, organizational innovation via the relocation of company headquarters or parent companies to more convenient locations than the home country was widespread, particularly against the development of high-level tax policy or to avoid confiscation. This strategy is the consequence of knowledge acquired through cloaking during the interwar years and World War II. Softer actions to improve the bargaining power of MNEs included the corruption of local politicians and bureaucrats. Siemens used these practices widely to ensure contracts for turnkey hospitals in Latin America during the 1950s and 1960s, for instance.Footnote 12 United Fruit Company had similar practices in Central America.Footnote 13 Finally, some companies worked to improve their image in their host countries, hoping to cultivate acceptance among local governments and populations. Maintaining legitimacy was another major issue. A subsidiary of Unilever employed this type of strategy in West Africa: for example, in the 1950s, it launched a communication campaign stressing how it contributed to economic and social development.Footnote 14 Similar strategies unfolded in Latin America and in the Middle East.Footnote 15 A long-term localization strategy, with the employment of nationals as managers, can help erase the “foreign” image of an MNE. Hence, in Australia, the public largely saw a subsidiary of the Dutch electronics multinational Philips as a domestic company that fought against Japanese—read “foreign”—competitors during the 1970s.Footnote 16 A similar practice was adopted by British companies in Africa.Footnote 17

One must also acknowledge that political risk created opportunities for companies capable of navigating unstable, sometimes hostile political environments to establish themselves in environments where most MNEs disinvested. That was the case for several British and U.S. firms in Nazi Germany, for example.Footnote 18 Similarly, German companies encountered success in colonial India, precisely because they were not British.Footnote 19

The above approaches focus mostly on actions and strategies that firms adopted. The ability to manage political risk properly is seen as a major issue. Yet another important dimension that shaped the political-risk strategies of MNEs during the Cold War was relations with home governments. For large countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, the presence of MNEs in emerging countries was part of their political and military interests within the context of the Cold War. In some extreme cases, such as those of Egypt, Iran, and Chile, that presence led to military interventions, coups d’état, or civil wars.Footnote 20 However, the defense of MNEs in emerging countries by small European nations—particularly the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland, which were large exporters of capital during this period— required a different action. Sweden and Switzerland were both neutral states without (former) colonies, highlighting a defining characteristic of many of these countries: they lacked military power and political ambitions in world affairs. Thus, state support for MNEs in risky environments took place in a different context. One would naturally wonder how small and powerless states could help their MNEs. However, that question has drawn very little attention in business history research. Most of the studies on the impact of governments on the competitiveness of multinationals from small European nations stress the importance of corporatism in domestic politics and coordinated welfare policies.Footnote 21 Those conditions provide a stable and flexible environment for multinationals in their home countries—but scholars have not addressed government support in other countries.Footnote 22

To contribute to the discussion of this issue, this article tackles the case of Switzerland. Despite its limited size in terms of population and GDP, Switzerland is not an undersized player in terms of outward foreign direct investment (FDI). During the second part of the twentieth century, Switzerland was a major exporter of capital. In 1973, it was the world's sixth-leading capital exporter, after the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, and France, and had the largest share of FDI to GDP after the Netherlands.Footnote 23 While it has exhibited substantial competitiveness and openness, Switzerland has a reputation of being a small, powerless state that bases its diplomacy and international action on neutrality, humanitarian aid, and conflict mediation. This image is largely a social construction that helped Swiss banks and MNEs benefit from some indifference and benevolence by host countries where they expanded.Footnote 24 The Red Cross is a good example of the convergence of interests between humanitarian action, business, and politics. Its International Committee, based in Geneva, gathered former federal government members, bankers, businesspeople, and bureaucrats, while the organization's various activities around the world during conflicts were led by local representatives of Swiss multinationals, such as in Nigeria during the civil war.Footnote 25

The contribution of the federal government to the expansion of banks and MNEs went beyond the positive image stemming from humanitarian action. In the Swiss political system since the end of the nineteenth century, trade associations and large enterprises have had a strong influence on social and economic policy.Footnote 26 They take official part in the lawmaking process through special commissions and cooperate directly with the federal administration and politicians. This weight is particularly important as members of the federal parliament are not professional politicians but rather citizens who maintain regular jobs.Footnote 27 In the specific field of foreign policy, the main objective of Swiss diplomacy was to protect the interests of exporters and investors throughout the world. Neutrality allowed Switzerland to avoid applying UN sanctions against the South African apartheid regime and establish diplomatic relations with North Vietnam in 1973, for example, which enabled Swiss firms to do business in these two countries.Footnote 28 However, the support of the federal government went beyond the mere establishment of diplomatic relations with politically risky countries.

This article investigates how companies from a small, neutral European country benefited from the support of their state in dealing with political risk during the Cold War, focusing on the case of the Swiss multinational Nestlé in Asian markets between 1945 and 1970. The company was established throughout Asia, with subsidiaries in place since the beginning of the twentieth century. The new environment that emerged after 1945 was thus a major challenge, and Nestlé had to cope with a broad variety of political risks. In the article, I address the question of how the Swiss government helped Nestlé deal with the new political risks that appeared in Asia between 1945 and 1970. To answer the question at hand, I draw mostly on primary sources from the Nestlé corporate archives in Vevey, Switzerland, and official papers in the Swiss Federal Archives in Bern.

The article includes four sections. The first section presents the general development of Nestlé from its foundation in the mid-nineteenth century until 1970, emphasizing how the evolution of the political environment shaped the organization of this global company in three major stages (free trade until 1914; custom protectionism and war from 1914 to 1945; and new risks between 1945 and 1970). The next section demonstrates the connections between Nestlé owners and managers on the one hand and Swiss politicians and elites on the other. The following section then analyzes the various new political risks facing Nestlé in Asia after 1945 and the role of the Swiss federal government in helping the company overcome them. Finally, the conclusion discusses the results and proposes some ideas for further research.

Nestlé as a Global Company

Nestlé & Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Co., the world's largest food company since 1971, was founded in 1905 via the merger of two companies in Switzerland: the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Co. (founded in 1866) and Henri Nestlé SA (1867), a manufacturer of powdered milk.Footnote 29 The newly merged company was a large multinational enterprise. It employed about three thousand people and had twenty factories in Switzerland, the United States, and five European countries.Footnote 30 Looking at the strategy and organization of Nestlé through 1970, one can divide its development into three main phases.

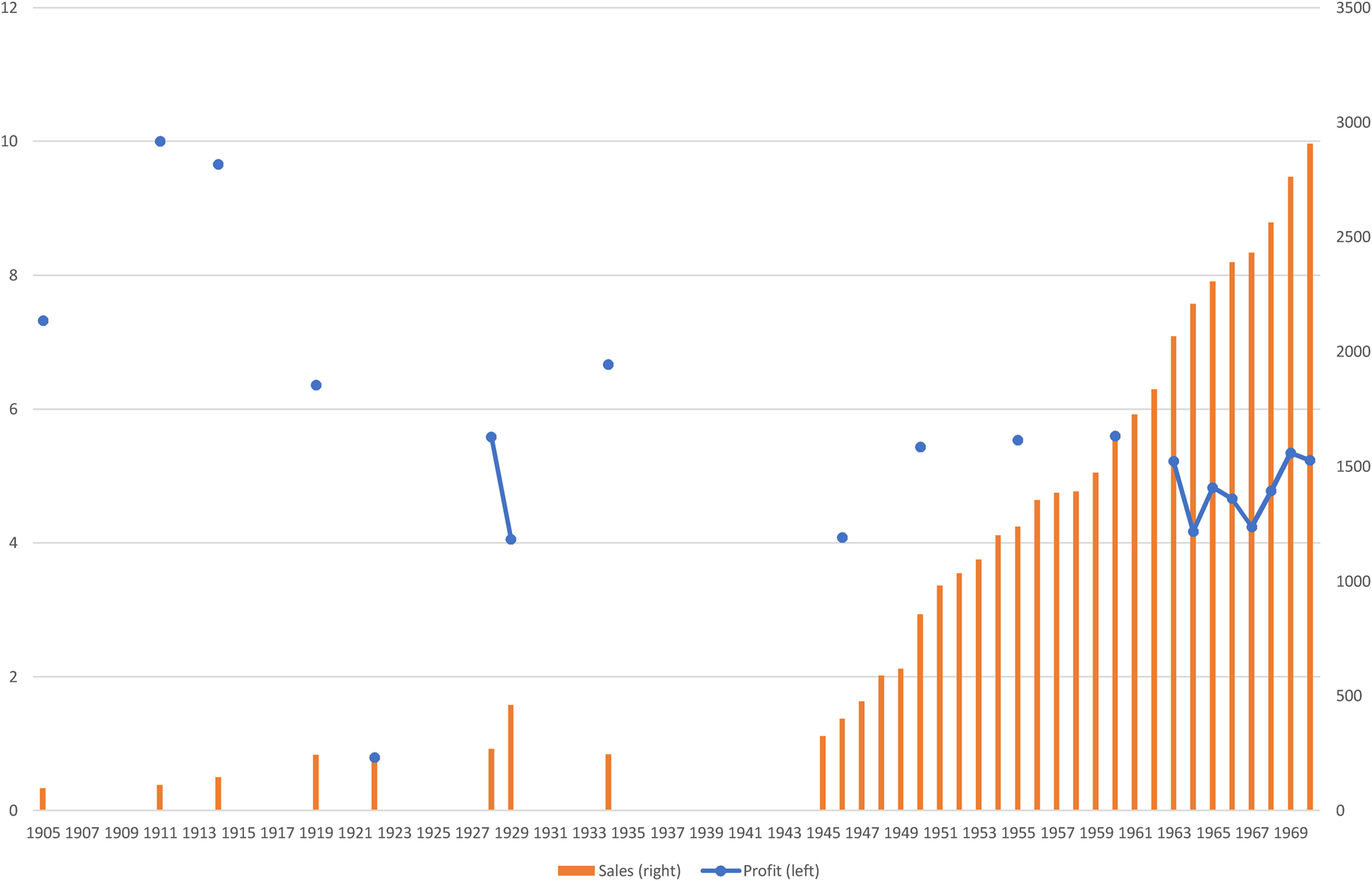

First, until the outbreak of World War I, Nestlé followed a path of development typical of the first global economy.Footnote 31 It was an MNE that organized itself globally based on the principles of free trade and free FDI. It had three product lines (condensed milk, powdered milk, and chocolate) and invested abroad following a market-seeking strategy.Footnote 32 A report published in 1958 explained that, during this period, “Nestlé was the only company that had, on a large scale, solved problems related to the distribution of high quality dairy products in countries where fresh milk was inexistent. Nestlé established a commercial network that drew on supplies from factories in traditional dairy countries and expanded to the most remote reaches of the globe.”Footnote 33 In particular, it took possession of plants in Australia (1908) and the Netherlands (1912) through mergers with local companies.Footnote 34 Between 1905 and 1914, Nestlé experienced slight growth (gross sales went from 97 to 145 million Swiss francs) and high profitability (around 8 percent) (see Figure 1). Moreover, Nestlé invested massively in the United States and Australia during World War I, providing the Allied armies with support.Footnote 35 In 1920, it owned a total of eighty plants around the world. This rapid development, however, led to financial difficulties and reorganization of the company; Nestlé eventually centralized control in 1922.

Figure 1. Gross sales (in million Swiss francs 1914) and net profit (as a %) of Nestlé, 1905–1970. (Source: Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, Nestlé 150 Years: Nutrition, Health, and Wellness, 1866–2016 [Vevey, 2016], appendix.)

Second, after World War I, Nestlé had to adapt to major changes and new types of political risk with the rise of protectionism and nationalism. In particular, the emergence and rise of customs taxes around the world during the interwar years threatened the company's global organization. The 1958 report explained that “economic nationalism and other obstacles to the old free-trade system multiplied during and after the First World War and, as it was necessary to satisfy the local demand that Nestlé had created, the company had to establish factories in distant and relatively few developed countries.”Footnote 36 Protectionism thus strengthened the globalization of production, including operations for machinery, automobiles, and other high-tech industries.Footnote 37 Nestlé opened milk and chocolate factories in eighteen new countries between 1921 and 1940.Footnote 38

The transplantation of production was, however, not the most important change with ties to political risk. In 1936, Nestlé reorganized and adopted a double-headquarters structure, echoing the examples of Royal Dutch Shell, Unilever, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche.Footnote 39 A holding company (Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Holding Co. Ltd.) was founded in Switzerland for the supervision of activities in the Swiss domestic market, continental Europe, and the sterling areas around the world. A new company, Unilac Inc., was also founded in Panama, with offices in the United States and the same capital ownership structure as Nestlé. Unilac took charge of business in the Western Hemisphere. If war were to break out in Europe and Nazi Germany to invade Switzerland, then, it would be possible for the company to pursue business throughout the globe through two legally different organizations. Moreover, Nestlé adopted a product-diversification strategy during this period (butter, dairy drinks with added vitamins, and Nescafé instant coffee). The lack of complete statistics for this period makes it difficult to discuss the effects of transplantation, diversification, and reorganization in terms of growth and profitability. Figure 1 suggests a period of slight growth during the 1920s, followed by a decade of stagnation.

Third, after 1945, Nestlé entered a new era characterized by rapid growth and a new kind of political risk. High economic growth obviously provided a fertile foundation for the development of Nestlé. Sales multiplied by a factor of roughly ten in real value between 1945 (324 million francs) and 1970 (2.9 billion francs), while profitability oscillated around 5 percent. This boom relied on two major elements. The first was organic growth rooted in a core selection of hit products like Nescafé. Between 1950 and 1970, the volume of sales of Nescafé around the world grew by more than 900 percent.Footnote 40 Nescafé's financial contribution to the company is unknown, but its impact must have been dramatic. Indeed, Nestlé expanded its locations of instant-coffee factories around the world during the post–World War II high-growth years. Non-Western countries were a major target of investment: Côte d'Ivoire (1962), the Philippines (1962), India (1965), Japan (1965), and Mexico (1967) all saw the establishment of Nescafé production sites.Footnote 41 The second basis of Nestlé's development during this period was external growth via acquisitions. This mergers and acquisitions strategy strengthened the company's geographic expansion and product diversification. The takeover of companies in Europe and the United States allowed Nestlé to enter new fields of the food business, including canned food, ice cream, frozen food, and mineral water.Footnote 42

However, despite this impressive development, the Swiss multinational faced new challenges in emerging countries. As the 1958 report explained, “Nestlé is facing new risks resulting from this expansion policy. The geographic dispersion of the organization and its factories made many sites more sensitive to those political upheavals that old centers have avoided. The threat of nationalization comes back periodically. In Czechoslovakia, Nestlé's market and five industrial organizations were lost due to nationalization; in Poland, a large factory was confiscated; and, in Yugoslavia, the company had to cease all activities.”Footnote 43 The new political risks linked to decolonization and communism were particularly important in Asia, a continent where Nestlé had expanded during the interwar years and that formed a basis for the company's growth after 1945.

Facing restrictions and confiscations in this highly risky environment was a substantial challenge for Nestlé. The company benefited from an important advantage, however: being Swiss. The management of the company was well aware of this fact and, in the 1958 report, developed a related argument: “Given its constitution, international status as a neutral state, renowned cultural traditions, and economic structure, Switzerland benefits from a unique reputation among under-developed countries. Efforts by Swiss citizens or companies in such countries can count on local support, providing a basis for smoother and freer implementation relative to larger Western countries.”Footnote 44 The successful development of Nestlé in Asia in the postwar era was not purely the result of the company's Swiss image and reputation, of course. The enterprise also benefited from the support of the Swiss federal government in overcoming various kinds of political risks throughout Asia.

The Connections between Nestlé and the Swiss Federal Government

Before analyzing how Nestlé benefited from the support of the Swiss federal government in coping with a broad range of new political risks in Asia, one should first have a basic understanding of the firm's relations with politicians and the federal administration. Recent works in political science, sociology, and history have demonstrated a general deep integration of Swiss elites, which formed through the boards of directors of large enterprises, the army, alumni societies, and politics, during the twentieth century.Footnote 45 These corporate networks strengthened during the interwar years and lasted until the 1990s, when a major change of corporate governance occurred, characterized by the internationalization of management and closer attention to shareholder value.

Nestlé is one of the most important companies at the core of the Swiss corporate network.Footnote 46 However, no case study has detailed how the enterprise built a dense linkage of relations with the federal government and the administration. The database Obelis (Swiss Elites Observatory) and the Swiss historical dictionary offer a broad range of information that delineates relations between Nestlé and the Swiss authorities.Footnote 47 Three kinds of links emerge from the data.

First, direct links existed between Nestlé and the federal parliament. Some directors and managers of Nestlé were also members of the National Council (federal parliament), including Auguste Roussy, Chairman of Nestlé from 1905 to 1940 and deputy of the Liberal-Democratic Party from 1919 to 1922, and Karl Obrecht, Nestlé board member and deputy of the Radical-Democratic Party from 1947 to 1965. These leaders were obviously major intermediaries between the company and the government.

Second, Nestlé built direct links with the federal administration. Some of its managers served in government before or after working for Nestlé. Robert Pahud is an excellent illustration of such a case. After obtaining a PhD in law at the University of Lausanne, he was district judge in Lausanne from 1913 to 1919, at which point he entered Nestlé. He worked for eighteen years at the company and then served in the federal administration beginning in 1936. He became head of the Office of Price Control in 1939 and remained in the position until retirement.Footnote 48 Another key intermediary of Nestlé in the federal administration after World War II was Edwin Stopper. Born in 1912, he was, during the war, an employee in the Federal Division of Commerce, an important unit in charge of supporting the international expansion of Swiss companies through exports and direct investments. He left the administration in 1952 and became the financial vice-director at Nestlé. Two years later, he returned to the government as a delegate for trade agreements. He was then appointed director of the Federal Administration of Finances (1960) and later ambassador and head of the Federal Division of Commerce (1961). Eventually, he became the president of the Swiss National Bank in 1966.Footnote 49

Third, Nestlé and the federal authorities were linked through indirect relations within a dense network connecting managers, families, army officers, local politicians, and alumni associations. The best example of this proximity is undoubtedly the figure of Max Petitpierre.Footnote 50 Born in 1899, he became a professor of law at the University of Neuchâtel and pursued a political career in the Radical-Democratic Party. In 1944, he was elected to the federal government and was in charge of foreign affairs (Political Department) until his retirement in 1961. He adopted a policy of neutrality and solidarity during the Cold War, taking a non-adhesive position toward international organizations such as the United Nations and the European Economic Community, and engagement in world affairs through good offices and humanitarian aid. After Petitpierre left the government, he was appointed chairman of Nestlé (1962) and occupied the position until 1970.

The dense network of relationships between Nestlé and the federal government and administration was beneficial to the company in navigating issues related to political risk around the world, a merit that became particularly important during World War II. Thanks to Swiss neutrality and the company's double-headquarters organization, Nestlé could continue doing business throughout the world during the war. In some countries, however, the company faced difficulties resulting from state intervention. This was particularly the case in Japan, Spain, and the United States, where controls on foreign exchange and export of capital made it difficult—sometimes impossible—to bring profits back to Switzerland.Footnote 51 In the case of Japan, the cooperation of the Swiss legation nevertheless enabled Nestlé to overcome this financial obstacle, as I will discuss below. As Switzerland was acting as a protecting power for Allied countries in Japan during the war, it needed a large amount of yen to develop its consular activities—hence private companies among which Nestlé offered yen to the Swiss legation in Japan and received in exchange Swiss francs in their home country.Footnote 52

A second important issue in Asia was how to make the Japanese military government recognize the Swiss—and consequently neutral—character of Nestlé's subsidiaries throughout the continent. Some of the subsidiaries, such as those in Hong Kong, Thailand, and Singapore, were legally owned by Unilac, the American headquarters of the Nestlé group, and thus considered enemy properties and confiscated by the Japanese army. The Swiss authorities intervened several times, in vain until 1943, to make the Japanese government acknowledge the Swiss character of these companies, calling attention to the fact that Unilac's shareholders were, by an overwhelming majority, Swiss citizens.Footnote 53 As for Nestlé, it supported the activities of Swiss diplomats in Axis countries during the war. For example, the Swiss legation in Tokyo had to engage numerous employees during World War II as Switzerland acted as a protecting power in the Japanese empire for several countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom. Hence, some employees of Nestlé Japan, who could not carry out their usual business, started working for the Swiss legation.Footnote 54

Consequently, the specific situation of World War II created an opportunity for strengthening relationships between Nestlé and the Swiss government in both Switzerland and belligerent countries. The multinational needed the backing of the government and supported its diplomatic activities abroad. This network was also crucial after 1945.

New Political Risks in Asia

In June 1946, correspondence between Edouard Müller, director of Unilac (Panama and Stamford, Connecticut), and André Perrochet, director of Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Holding (Switzerland), showed a general optimism regarding the recovery of business as usual around the world, particularly in Asia, a continent where Nestlé's activities were under the control of Unilac at that time. Müller prepared a report on the “developments in markets liberated from the Japanese occupation or influence” for the Swiss headquarters.Footnote 55 Nestlé had reestablished its organization and restarted business in Ceylon, China, India, Malaya, the Philippines, and Thailand. It imported dairy goods from Australia and the United States and sold them throughout Asia, just as it had during the free-trade era of the first wave of globalization.

The only restraint concerned the Dutch Indies. Müller confessed that “until the political situation clears, there is no prospect of trading. . . . Against the reopening of operations in the Netherlands East Indies, we have completed our European staff plans and are retaining key members of the Asiatic staff, on which nucleus a fuller organization can be built up very short notice.”Footnote 56 Nestlé was in a state of uncertainty in the Dutch Indies due to the declaration of independence of Indonesia, revolutionary conditions, and civil war. The company was ready to restart a business in a colonized environment or shift to an organization with closer connections to the local population, depending on the situation. Uncertainty and difficulties resulting from postcolonial independence, nationalism, social revolution, and the threat of communism were not unique to Indonesia, however; a few years later, Nestlé had no choice but to leave China, as most Swiss multinationals did.Footnote 57 The Switzerland-based subsidiary Milk Products (China) Ltd. closed its branches in China in September 1950 and underwent liquidation two years later.Footnote 58

Actually, Asia was a much riskier environment than Müller and Perrochet expected in 1946. During the following decades, Western MNEs had to face a broad range of new political risks that challenged their presence and extension in this part of the world. The control of foreign exchange, the control of inward FDI, and the lack of protection for trademarks were major issues for Nestlé, which used the support from the Swiss federal government as much as it could to handle these situations.

The control of foreign exchange (Japan). During the interwar years, Nestlé was present in Japan through two separate firms: Nestlé Products Ltd., Kobe Branch, an import and distribution subsidiary founded in 1913, and Awaji Rennyu KK (ARKK), a dairy goods–manufacturing company founded in 1934.Footnote 59 Nestlé's Swiss headquarters had decided to stay in Japan during World War II—although it was not possible to do business there—because already having a presence in the country after the war ended would confer a competitive advantage to the company.

In 1949, Nestlé obtained authorization to restart the import and distribution of food products in Japan.Footnote 60 The following year, the company was able to resume the manufacturing of condensed milk. The fierce competitiveness of the domestic market led Nestlé to reorganize its business in 1954, with the closure of one of its two factories and the concentration of production in the Hirota plant.Footnote 61 Business hummed during the first part of the 1950s (see Table 1), as sales expanded from 2.2 million francs in 1950 to 9.8 million in 1954. After posting a deficit in its first year, the business was profitable despite a gentle decrease in profitability after 1952 stemming from tough competition.

Table 1 Gross Sales and Profits of Nestlé in Japan, in Current Swiss Francs, 1950–1954

Source: Considérations générales sur la situation de nos affaires au Japon, 20 June 1955, 4600, Archives Nestlé, Vevey, Switzerland.

Note: Data is unknown after 1954.

For Nestlé, the problem centered on repatriating these profits to Switzerland. It had accumulated more than 633,000 francs from 1950 to 1954, along with the monthly royalties of more than 6,000 francs that ARKK owed Afico SA, a subsidiary of Nestlé, for technical assistance (use of patents). In December 1954, the total amount for Afico blocked in Japan—that is, impossible to bring back to Switzerland—came to 12.2 million yen (about 146,000 francs).Footnote 62 The Japanese authorities had in 1949 adopted a Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Law: legislation that gave the government the power to control the use of foreign currency in the country.Footnote 63 The objective was to apply foreign hard currency toward industrial development, particularly to import the necessary raw materials and technologies, in a profitable fashion.Footnote 64 The government did not allow the few foreign MNEs in the country to use dollars or francs to repatriate their profits.

The Swiss management of Nestlé had no intention to reinvest in the country. Edmond Mandelert, the local director in Kobe, argued in 1955 that “we haven't any interest for Japanese economy.” The food industry was too competitive, and cultural difference was difficult to deal with: “My personal impression is that we have no really serious support, neither from our lawyers, nor from our own domestic staff. Japanese are not only nationalist, but also clearly xenophobic; roughly brought up, educated since childhood to dissimulate his thought, he cannot feel any will of personal contact and mutual trust.”Footnote 65 Leaving Japan was considered a serious option but, again, it was impossible to move company assets back to Switzerland.

In these conditions, Nestlé sought the assistance of the Swiss federal government. It first made its presence felt in government circles during 1952 and 1953 through the Groupement des Holdings Industrielles (GHI), an organization that various large Swiss multinationals set up in 1942 to defend their common interests.Footnote 66 GHI lobbied the Federal Political Department (foreign affairs), albeit unsuccessfully.Footnote 67 A few years later, Nestlé again approached the federal government, but this time alone. In May 1956, the Swiss legation in Tokyo solicited the Japanese authorities several times but was unable to apply enough pressure due to a balance of trade largely favorable to Switzerland (via exports of machinery and chemical products). The Division of Commerce (Federal Department of Public Economy) thus advised the government not to contact the Japanese embassy in Switzerland on the matter.Footnote 68 This shows that there were sometimes contradictions between the interests of exporters, which wanted to maintain access to the Japanese market, and those of multinationals with subsidiaries in the country, which wanted to repatriate their profits. In the case of Japan, the first category of interests was stronger in the early 1950s, as most companies had left Japan before and during World War II.Footnote 69

Finally, a pragmatic measure allowed Nestlé to repatriate its profits and royalties. The Swiss government reopened the system of exchange of currencies with the multinational: Nestlé transferred its yen to the Swiss embassy for its own use and received francs in Switzerland. The Division of Commerce wrote in May 1956 to the Swiss Legation in Tokyo that “there is no objection against your taking Nestlé's assets back according to what you and the Division of Administrative Affairs [in Switzerland] had agreed to. However, we advise you again to observe all the necessary discretion for this operation and to make sure it is not likely to inconvenience the Legation.”Footnote 70 Consequently, Nestlé was able to remain in Japan and make full use of its profits during the 1950s. In 1960, the company reorganized its business in Japan by closing Nestlé Products Ltd., Kobe Branch, and transforming ARKK into Nestlé Japan, a fully owned subsidiary responsible for all operations in the country. Foreign exchange remained under the strict control of the Japanese authorities, but Nestlé had other plans that required local investment: moving out of an overcompetitive dairy business and refocusing on a new activity: the manufacturing and sales of Nescafé. This strategy put Nestlé on a fast growth track in the Japanese market during the ensuing decades.

The control of inward FDI (India). Nestlé's opening of a production center in India is an excellent example of the company's cooperation with the Swiss federal government in a highly risky environment. The new Indian government adopted a rather interventionist policy, strictly controlling the activities of foreign companies in its territory.Footnote 71 Nestlé was active in the Indian market during the colonial era but did not have an actual factory location in the country. Instead, it imported milk products and chocolate from the United States, Australia, and South Africa.Footnote 72

In the years following the end of World War II, Nestlé management discussed the opportunity to open a production unit in India, as the new government adopted a protectionist policy and import controls thus became a risk. In March 1946, Müller, director of the U.S. headquarters, noted that “if Indies are going to endure the influence from Moscow and to become communist, there is clearly not so much to hope.”Footnote 73 The following year, the Swiss headquarters echoed a similar sentiment, saying, “we can congratulate ourselves on not being involved in any manufacturing scheme in India, the more so as with the attitude Great-Britain is taking, that are great risks that the internal situation of the above mentioned country will in future greatly deteriorate, anyhow as far as any industrial establishment is concerned.”Footnote 74 Nestlé thus faced import limitations through restrictive licenses from the Indian authorities. In May 1950, Hans J. Wolflisberg, president of Nestlé in the United States, met for lunch with Dr. K. C. K. E. Raja, director general of health services in India, at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva. By that time, the Indian government was developing several programs for transplanting condensed-milk factories with the WHO and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to support the human development of its population.Footnote 75 Nestlé, however, was not interested; Wolflisberg only complained about the “very difficult import license situation with which our associates in India are faced,” but he could not obtain an extension of licenses from his counterpart.Footnote 76

Five years later, in September 1955, Enrico Bignami, executive director of Nestlé Alimentana (the Swiss headquarters), made a business trip to India with a new idea in mind: manufacturing Nescafé in the country.Footnote 77 Although the market for milk products and chocolate was small and very competitive, selling Nescafé held considerable promise. In 1953 and 1954, Nestlé sold more than seven thousand cases a year in India at a profit margin of nearly 20 percent.Footnote 78 The company asked the Indian government in January 1956 for authorization to manufacture instant coffee. Based on the example of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche, which produced vitamins in India, Nestlé proposed setting up a joint venture with an Indian partner, which would have a majority stake, and then offering technical assistance for production against royalties as a percentage of sales.Footnote 79 The Indian government refused, however, because it only accepted the principle of fixed royalties and because instant coffee was not a strategic product for the country's economic and social development. Therefore, Nestlé changed its strategy. It accepted the principle so as to engage in the production of powdered milk, for humanitarian purposes, with the aim of engaging in the production of Nescafé once established in the country. Indeed, a note to executives signed in 1957 mentioned that “after some years of operation, we should have the volume and quality necessary to justify a spray plant if a switch of production seems reasonable in light of the local conditions at the time. The possibility of manufacturing Nescafé would also then be taken into account.”Footnote 80

The new challenge was to persuade the Indian government to accept an investment from Nestlé. The company used a technical issue—the need to nurture a local dairy-farming industry to ensure the supply of high-quality fresh milk—to enable the Swiss federal government to intervene discreetly but effectively. The objective was to present the project not as the investment of a private company but rather as a contribution from the neutral Switzerland government toward the human and social development of India. Nestlé used political arguments when approaching the federal administration. In a January 1958 letter to the president of the Swiss Commission for the Coordination of Technical Assistance, Nestlé asked the government to officially offer India the dispatch of Swiss agronomists specializing in the milk industry to support the improvement of agriculture in India. It argued that such cooperation was “a way to preserve the basic ideas of the free world.”Footnote 81 Nestlé leadership used similar arguments when writing to Petitpierre, the minister in charge of foreign affairs, around the same time: “If our company goes on, it shall do so thinking only from a long-term perspective; [moreover,] the federal authorities . . . could see, in the intensification of relationships in Europe, especially Switzerland, and Asian countries that are still free, the milestones of the consolidation of political and social stability on the latter.”Footnote 82

For the Swiss authorities, their role was to present this case of technical assistance as a humanitarian project and not a purely private project by a multinational enterprise. Petitpierre asked his ambassador in New Delhi to meet with the Indian authorities and gave him a precise objective: “Considering the extreme susceptibility often evident in so-called ‘underdeveloped countries,’ the federal authorities, before making a decision, must be ensured that the Indian authorities have no objection to the combination of bilateral technical assistance with a project by a private industrial company.”Footnote 83 In a note prepared half a year later, Petitpierre mentioned that the ambassador “informed the Indian government that Nestlé would be founding this business in India not to make some profits but within the context of Indo-Swiss economic cooperation. He can ensure the government that Nestlé engaged in this business inspired by the Federal Council, despite the risks it may face.”Footnote 84

At the same time, the managers of Nestlé negotiated directly with India's minister of industry. Together, they implemented technical surveys to find a suitable region in which to develop a modern dairy industry and carried out the industrial production of milk products. For the Indian government, the investment of foreign companies in the industry was a welcome development. That year, it had adopted a new import substitution industrialization policy. In August 1958, it approved the investment in milk products by three Western companies: Nestlé, Glaxo, and Horlicks.Footnote 85 Nestlé, however, wielded a monopoly on sweetened condensed milk.

This approach to the Indian authorities was successful. In 1959, the Swiss government sent an official expert in agriculture to modernize the dairy industry in India. Funding for this technical assistance came from the federal budget, although Nestlé initially offered to cover the costs.Footnote 86 The company also made an application to the Ministry of Finance to create a new company for making milk products in India: Food Specialties (Private) Ltd., controlled by Nestlé's Bahamas-based holding company (90 percent of capital) and Indian nationals (10 percent).Footnote 87 The first factory opened in Moga, Punjab, in 1961.Footnote 88 Four years later, in 1965, Nestlé started to manufacture Nescafé at the site.Footnote 89 In 1980, Food Specialties employed about 1,100 people and produced more than one thousand tons of instant coffee for the domestic market and exports to the USSR and Hungary.Footnote 90

Struggles against trademark infringement (China and Vietnam). Brands are a key asset of global consumer-goods companies like Nestlé, which makes protection a major issue when a company enters a new country or faces political change in any market. Some MNEs, like Beiersdorf, built a specific organization with subsidiaries in neutral countries to prevent the confiscation of their brands in the case of war.Footnote 91 Brand protection was also a major reason why Nestlé stayed in Japan during World War II.Footnote 92 After 1945, the advent of new governments in former colonies and communist China was a challenge for Western companies, as the relevant authorities were not particularly keen on protecting foreign brands in their territories. Facing similar challenges in China and Vietnam, Nestlé tried—although in vain—to use the Swiss federal government to strengthen its position.

In January 1947, Nestlé's headquarters in Vevey worried about the company's activities in China, as civil war was expanding. In a letter to the U.S. headquarters, which oversaw East Asian businesses, officials underlined the fact that, despite the nonexistence of any treaty between Switzerland and China, the notes exchanged in 1946 between the Swiss federal government and the Chinese legation in Bern explicitly mentioned that Swiss individuals and companies had the right to establish and pursue commerce freely in China.Footnote 93 The new communist government did not recognize this agreement, though, and Nestlé had no choice but to close its Chinese branch in September 1950.Footnote 94 Consequently, Nestlé management feared that local enterprises would infringe on its trademarks while the company was absent from China. Together with the Swiss chemical companies Ciba, Geigy, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Nestlé directly asked the Chinese communist government for legal protection of their trademarks. However, nothing came of the request; the Swiss authorities, meanwhile, could not support their multinationals due to the lack of any treaty between the countries at the time.Footnote 95

A few years later, a similar problem occurred in South Vietnam. Some local manufacturers used imitations of Nestlé trademarks to sell dairy products and instant coffee in 1957. Nestlé went to court but lost because the Vietnamese judges did not consider the products to be sufficiently similar.Footnote 96 The company responded by asking the Swiss consul in Saigon to intervene against the local authorities. The Swiss authorities refused to act directly, however, fearing that an intervention would result in harsher trade restrictions on Swiss goods. Watch components, chemical products, and textiles were major exports in the 1950s, while imports were very low, making the balance of trade very profitable for Switzerland.Footnote 97 In these conditions, keeping a low profile toward the South Vietnamese authorities was necessary. Instead, the Swiss government advised Nestlé to intervene on its own power to help cultivate an “influential business milieu in Viet Nam [and stress that] it is not in the country's interest to continue tolerating the imitation of foreign brands.”Footnote 98 Jean Constant Corthésy, CEO of Nestlé Alimentana, met with local officials and businesspeople while he was in Vietnam in 1960. The discussions had no impact on trademark infringement, however; imitations continued, and the South Vietnamese government instituted a more restrictive trade policy anyway in 1965, specifically banning imports of instant coffee.Footnote 99

Conclusion

This article discusses Nestlé's strategy in Asia after World War II in response to new kinds of political risks and the contributions of the Swiss federal government in supporting the multinational's long-term activities in the corresponding countries. Risks differed from nation to nation, and the role of the Swiss authorities varied accordingly. Neutrality was an important factor in the support of Nestlé's expansion in Asia and represented an opportunity to enhance presence in some politically risky environments. At first, neutrality enabled the Swiss embassy to maintain a presence in Japan during World War II. The embassy consequently established a friendly, cooperative connection with Nestlé, which was one of the only foreign firms to stay in the country during the conflict. These relations and the consistent presence of a diplomatic infrastructure in Japan enabled the transfer of Nestlé's profits in the mid-1950s. Of course, this case is not unique. In 1969, the United States established the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, an organization that offered financial support to American MNEs that could not repatriate profits.Footnote 100 Switzerland signed a broad range of bilateral treaties to protect FDI starting in the 1960s, especially with African countries.Footnote 101 However, these were institutionalized ways to avoid control over the repatriation of profits. During the 1950s, as well as during World War II, Switzerland directly applied its diplomatic infrastructure in carrying out these practices, which meant that the state was directly involved with multinationals. Second, the Swiss aid policy explicitly supported Nestlé's entry into India. While private multinationals could not invest there to manufacture instant coffee, a company working with the government of a neutral and humanitarian country like Switzerland had the ability to produce milk—and that effort quickly shifted to manufacturing Nescafé.

Although neutrality made it possible for the Swiss government to offer its services to Nestlé in Japan and India, that support had its limits. Above all, the aim of the government was to be discreet and avoid conflict in order to protect its exports of goods and capital and maintain access to markets. Moreover, as the cases of Japan in the early 1950s and Vietnam in the 1960s suggest, contradictions sometimes existed between the interests of Swiss exporters and those of Swiss multinationals abroad. As the balance of trade was largely positive for Switzerland in these two cases, the federal government put a priority on keeping that same trend intact: a key objective for a small country without natural resources.

Lastly, Nestlé did not rely fully on the Swiss federal government to solve political risks in Asia during the Cold War. The multinational also adopted a broad range of internal measures to fix many issues. For example, the need to train and transmit corporate culture to local middle management, particularly in Japan and Singapore, led Nestlé to set up a business school in Switzerland, IMEDE (Institut pour l'Etude des Méthodes de Direction de l'Entreprise), in 1957.Footnote 102 In Vietnam, Nestlé shifted the origin of its exports from France to the United States in 1955 to keep its products’ image away from the French imperial power in light of the war.Footnote 103 The actions against political risk were thus numerous, and government support was just one of them. Government involvement was important in some major markets, but it should not be overstated.

Beyond the case of Nestlé in Asia, this article offers important implications for research on the expansion of foreign firms in emerging markets after World War II. Intervention by the governments of large countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and France to protect their multinationals in emerging countries during the Cold War was part of a larger political action aiming to protect economic and military interests. However, the cases of small and/or neutral countries are different, as the exploratory research here demonstrates. The small size of Switzerland played a major role in shaping a dense network of corporate-government relations. This was possible because of the smaller number of national elites, who had numerous opportunities to socialize and meet. But the density of the relations was also vital in enabling enterprises to grow in foreign markets, considering that the domestic market was insufficient to allow the development of any large firms. However, the support of the government also extended beyond the national level, unlike the democratic corporatism model posited by Peter Katzenstein.Footnote 104 In addition, neutrality facilitated intervention by the government to support its firms abroad. Further research on Dutch, Swedish, and Swiss MNEs will refine the understanding of how small, and apparently powerless, states supported their enterprises in politically risky countries during the Cold War.