Older adults (generally considered as those 65 years of age and older) are a growing segment of the Canadian population, and approximately 22 per cent of community-dwelling older adults are living with frailty (Rockwood & Mitnitski, Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2011). Frailty has emerged as an important characteristic of health (Rockwood & Howlett, Reference Rockwood and Howlett2018). The aging population and the rising prevalence of frailty amongst older adults suggests that frailty should be a public health priority (Cesari, Reference Cesari2019).

The term “frail” is used to broadly describe a person’s vulnerability and risk for developing health problems (Cesari, Reference Cesari2019; Junius-Walker et al., Reference Junius-Walker, Onder, Soleymani, Wiese, Albaina and Bernabei2018). Specifically, clinical frailty has been defined as a syndrome and age-related accumulation of deficits across multiple body systems that result in a dynamic risk state (Rockwood & Howlett, Reference Rockwood and Howlett2018). Frailty may predict outcomes more accurately than age or co-morbidities (Maxwell & Wang, Reference Maxwell and Wang2017). Several longitudinal studies have established frailty as a significant predictor of adverse health outcomes such as falls, reduced mobility, reduced quality-of-life (Crocker et al., Reference Crocker, Brown, Clegg, Farley, Franklin and Simpkins2019), hospital admission/readmission (Kojima, Reference Kojima2016), and death (Kojima, Iliffe, & Walters, Reference Kojima, Iliffe and Walters2018; Saum et al., Reference Saum, Dieffenback, Muller, Holleczek, Hauer and Brenner2014) amongst community-dwelling older adults. Screening for frailty could therefore be a powerful prognostic tool to prompt assessments and provide tailored interventions to optimize health (Rolfson et al., Reference Rolfson, Heckman, Bagshaw, Robertson and Hirdes2018).

Research efforts over the past 30 years aimed at defining, measuring, and validating this health state, have aimed to apply frailty as a risk stratification tool to support older adults with improving health and avoiding adverse health outcomes (Ofori-Asenso et al., Reference Ofori-Asenso, Chin, Mazidi, Zomer, Ilomaki and Zullo2019). These advances have led to widespread use of the term “frail” in health care and frailty screening at the point of entry to acute health care settings (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Zuege, Rolfson, Opgenorth, Hudson and Stelfox2019). Primary care providers play an important role in assessing for and identifying frailty, although the topic of frailty can pose challenges when it comes to effective health care communication (Lawless, Archibald, Ambagtsheer, & Kitson, Reference Lawless, Archibald, Ambagtsheer and Kitson2020). This is because frailty is a complex term and concept that can have many meanings and interpretations (Lawless et al., Reference Lawless, Archibald, Ambagtsheer and Kitson2020).

In addition to and despite the benefits of discussing frailty, “frail” may be a pejorative term with negative connotations (McNally, Reference McNally2017). The later stages of life are frequently viewed as a period of decline, and negative age-related stereotypes have been increasing over time (Ng, Allore, Trentalange, Monin, & Levy, Reference Ng, Allore, Trentalange, Monin and Levy2015). Diagnosing older adults as “frail” could further emphasize challenges related to aging. Negative perceptions of aging also predict individuals’ mortality and poor health outcomes (Warmoth, Tarrant, Abraham, & Lang, Reference Warmoth, Tarrant, Abraham and Lang2016; Wurm, Diehl, Kornadt, Westerhof, & Wahl, Reference Wurm, Diehl, Kornadt, Westerhof and Wahl2017). Considering oneself as “frail”, for example, has been linked to feelings of guilt or inferiority, influencing health and health care utilization (Ebrahimi, Wilhelmson, Ekland, Moore, & Jakobsson, Reference Ebrahimi, Wilhelmson, Ekland, Moore and Jakobsson2013; Salguero et al., Reference Salguero, Ferri-Guerra, Mohammed, Baskaran, Aparicio-Ugarriza and Mintzer2019). Associations between attitudes and health outcomes may be explained by stereotype embodiment theory, whereby stereotypes become embodied into one’s self-perception and negatively influence health and overall functioning (Fawsitt & Setti, Reference Fawsitt and Setti2017). It is therefore important to actively engage older adults in research to understand perceptions of frailty language and diagnosis to avoid stigmatizing persons and inform care practices (Kirkland & The OA-Involve Team, Reference Kirkland2017).

Exploring perceptions of frailty language, the impact of language on older adults, and examining frailty-related attitudes of health care professionals have been identified as research priorities (Ambagtsheer et al., Reference Ambagtsheer, Beilby, Visvanathan, Dent, Yu and Braunack-Mayer2019; Bethell et al., Reference Bethell, Puts, Schroder Sattar, Choate, Clarke and Cowan2019). Older adults’ perceptions of aging and health functioning have been examined in one systematic review (Warmoth, Tarrant, et al., Reference Warmoth, Tarrant, Abraham and Lang2016). However, research exploring older adults’ perceptions of the term “frail” and frailty diagnosis is limited. Hence, we completed a scoping review to: (1) map the breadth of research literature exploring perceptions of frailty language, the meaning of the term “frail”, perceived impacts; and (2) summarize study findings. Recommendations for the use of frailty language by researchers and health care professionals are provided.

Methods

A scoping review is useful for mapping the extent and nature of research, and summarizing findings from studies with diverse methodologies (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco and Perrier2014). We followed a scoping review framework with stages including: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies through an appropriate search strategy, (3) study selection through screening by title and abstract, then by full text using inclusion and exclusion criteria, (4) charting the data by extracting information relevant to the review from included articles, and (5) collating the data, summarizing, and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco and Perrier2014).

Search Strategy

Together with a university librarian, we developed a search strategy of databases (AgeLine, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], Embase, MEDLINE®, PsycInfo) and Google Scholar using MeSH terms and keywords. Search terms included: frail, frail elderly, senior, geriatrics OR aged, AND terminology as topic, language, term, semantics AND experience, perceptions, OR attitude. Additional articles were collected from the reference lists of included studies, existing networks, and relevant organizations (e.g., International Federation on Aging) were hand-searched (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco and Perrier2014).

Study Inclusion Criteria

Included articles were primary research studies published in English with full text available from 1994 (when a seminal article conceptualizing frailty was published) to February 2019 (Rockwood, Fox, Stolee, Robertson, & Beattie, Reference Rockwood, Fox, Stolee, Robertson and Beattie1994). Included studies described the perceptions, meaning, and perceived implications of frailty language, and/or the diagnosis of frailty amongst community-dwelling older adults (i.e., not living in long-term care).

Study Selection and Analysis

Titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion by single authors in DistillerSR, a systematic review software program (Evidence Partners, 2020). Selected articles’ full text was then reviewed independently for inclusion by two authors. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third author.

The authors independently charted and extracted descriptive data (e.g., author, country) from the included studies in Microsoft Excel (2020) in duplicate for accuracy and credibility, using a charting form of categories created and piloted for this study (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco and Perrier2014). The authors then independently analyzed the findings from three of the included studies by charting and extracting data describing the meaning of the term “frail”, perceptions of frailty language/being diagnosed with frailty, and implications (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco and Perrier2014). Afterwards, each author searched for common themes and patterns across the study findings and created new categories representing themes. The authors then met together for researcher triangulation (i.e., to compare their findings) and agreed upon a final charting form. Subsequently, data from all the included studies were analyzed by two authors using the agreed upon form. New themes that emerged during analysis were discussed by the authors, and the charting form was revised if agreed upon. Finally, all of the extracted data were collated to produce a description of the studies and a summary of themes (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco and Perrier2014).

Findings

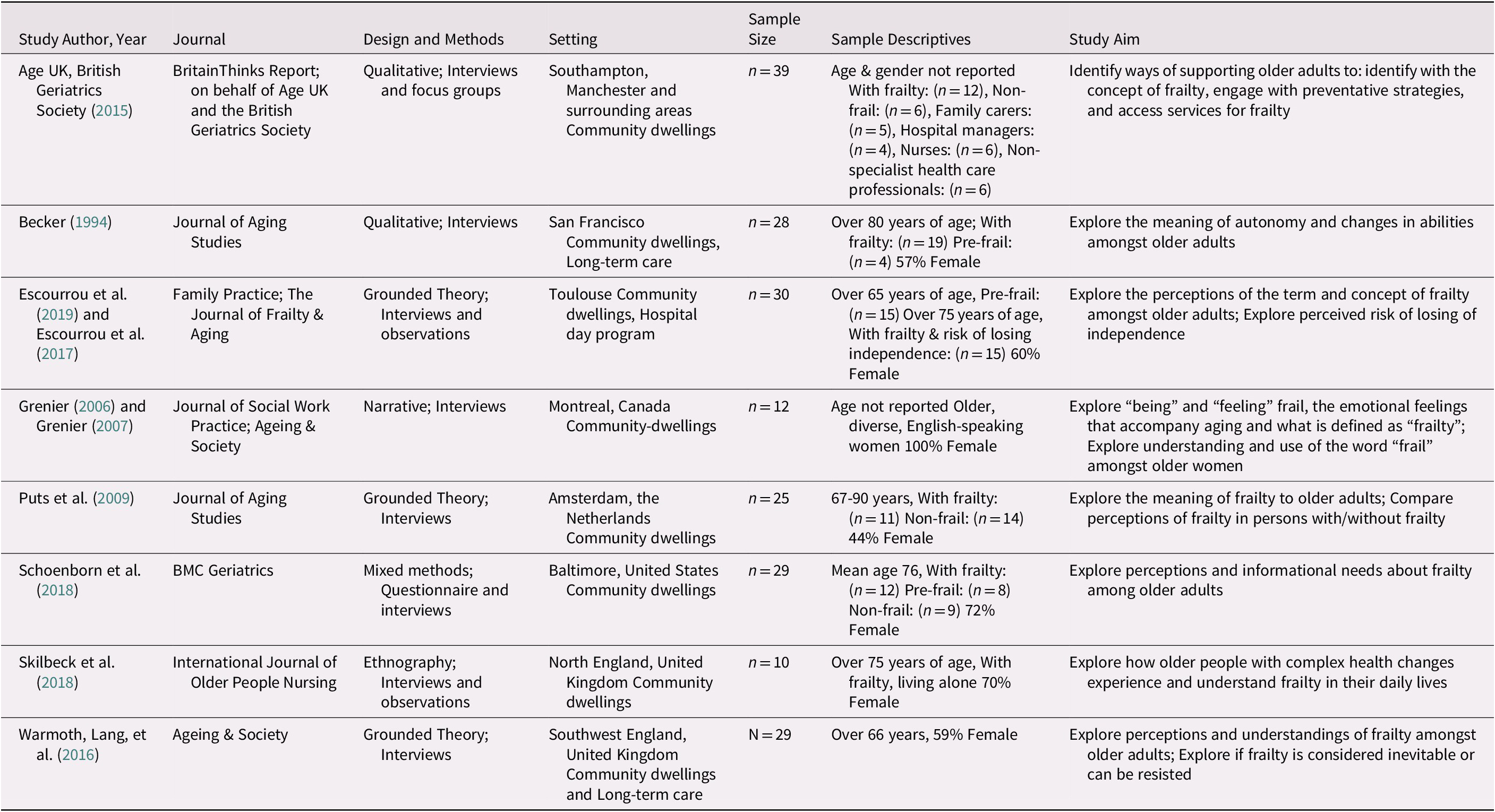

The initial search generated 4,639 articles, and after title/abstract screening, the full text of 73 articles was reviewed. The final sample included 10 articles, representing eight studies (see Figure 1). Overall, a small number of primary studies have explored perceptions of frailty amongst community-dwelling older adults with research primarily taking place in Western countries (see Table 1). Analysis of the definition, perceptions, and implications of frailty language resulted in three themes:(1) understanding frailty as an inevitable age-related decline in multiple domains (2) perceiving frailty as a generalizing label, and (3) impact of frailty language on health and health care utilization.

Figure 1. Search flow. From: Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C, Mulrow, C. D., et al. (Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Table 1. Included studies

Breadth and Characteristics of Primary Studies

Included studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 3), Canada (n = 1), the United States (n = 2), France (n = 1) and the Netherlands (n = 1), and were published most often in the following journals: Journal of Aging Studies (n = 2) and Ageing & Society (n = 2). A qualitative (n = 7) or mixed-methods design (n = 1) was used for each study. Participants were defined as older adults ranging in age from 55 to 98. The proportion of female participants (ranging from 44 to 100%) was greater than that of males on average.

Study authors most commonly defined frailty as a phenotype (n = 4) according to Fried et al.’s definition (Reference Fried, Tangen, Walston, Newman, Hirsch and Gottdiener2001), or as an accumulation of deficits (n = 2), based on the model by Rockwood and Mitnitski (Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2011). Commonly used frailty assessment tools were the Frailty Index (n = 2) based on the accumulation of deficits model (Rockwood & Mitnitski, Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2011) and the Fried Phenotype (n = 2), which focuses on physical criteria (Fried et al., Reference Fried, Tangen, Walston, Newman, Hirsch and Gottdiener2001).

Narrative Summary of Themes

Theme 1: Understanding frailty as an inevitable, age-related decline in multiple domains

Amongst participants, the term “frail” referred to a multidimensional quality or state of being (Warmoth, Lang et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016) with interrelated physical, psychological, and social domains. Decline in one domain resulted in losses in another domain (Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Skilbeck, Arthur, & Seymour, Reference Skilbeck, Arthur and Seymour2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). All domains of frailty were associated with perceptions of loss such as deficits in function, distressed mood (e.g., growing symptoms of anxiety, depression), and changes to identity. The multiplicity of losses was perceived as accumulating and ultimately translating into the overall loss of independence, control, dignity, certainty, confidence, and one’s sense of personhood, which led to becoming frail (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens, & Deeg, Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016).

Frailty was described as a dichotomous classification, meaning that persons were either frail or not (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015). Participants commonly described a pattern of events of “becoming frail”, whereby persons experienced a gradual decrease in their abilities over time (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Becker, Reference Becker1994; Skilbeck et al., Reference Skilbeck, Arthur and Seymour2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Some participants described a specific health event/turning point (e.g., stroke or fall), which caused persons to cross a threshold and become “frail” (Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Skilbeck et al., Reference Skilbeck, Arthur and Seymour2018). Once persons were living with frailty, participants perceived that further decline would follow (Grenier, Reference Grenier2006).

The process of “becoming frail” was described as an inevitable part of the aging process (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). A participant explained, “Frailty is not something that you can prevent, you cannot do anything, it just happens when you get older” (Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009, p. 264). In contrast, some participants who were described as “not frail /pre-frail” perceived that frailty could be delayed or reversed through activities and “doing things” (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016, p. 1.494).

Physical frailty

Participants’ descriptions of frailty focused predominantly on aspects of physical frailty characterized as: losses in mobility, changes to physical appearance (e.g., low body weight and pale skin), and the presence of comorbidities (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Participants described individuals living with frailty as fragile, falling often, and easily sustaining fractures (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009). A participant explained:

Frailty is frailty physically, I think frailty is someone whose bones may crack, …someone who is slightly bent over…pallid complexion…withdrawn … no longer able to take care of myself (Grenier, Reference Grenier2007, p. 433).

Psychological frailty

Participants referred to psychological frailty as decline/losses in mood, attitude, self-esteem, and cognitive function. Negative emotional states such as depression, anxiety or fear, having limited strategies to cope with emotions, and a sense of having one’s identity threatened were symptoms of psychological frailty (Becker, Reference Becker1994; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Skilbeck et al., Reference Skilbeck, Arthur and Seymour2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Individuals who were dependent on others, lacked confidence, and had a negative outlook on life were perceived as having “a frail state of mind” (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018). Cognitive changes (e.g., forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating) were also perceived as characteristics of psychological frailty (Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009). Overall, psychological frailty was perceived as contributing to an emotional experience that led to classification and self-identification as frail (Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007).

Social frailty

Participants described social frailty as losses/decline in social interactions, feelings of loneliness (Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009), and disengagement behaviours (e.g., refusing invitations to social gatherings, reducing phone calls to peers/family members) (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016), which compounded losses that were common in later life. Individuals living with social frailty were described as withdrawing from participation in social events, while at the same time being excluded or not invited to activities because of limitations (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Social isolation was therefore perceived as a cause and result of frailty. Being excluded from social activities was perceived as reducing motivation to participate in future events, which led to further isolation (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Participants explained that social frailty was exacerbated by environmental constraints (e.g., limited access to transportation, poor building accessibility, financial concerns) that resulted in social disconnection (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019). Overall, regardless of the domain, a sense of loss was often associated with older adults’ understanding of frailty.

Theme 2: Perceiving frailty as a generalizing label

Frailty language (i.e., using the term “frail”) and being diagnosed as frail were perceived as undesirable and “frail” was perceived as being a generalizing label. Participants associated the terms “frail” and “frailty” with negative age-related stereotypes (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). The term “frail” was associated with stereotypes of older adults who were, “grey-haired, hunched, wobbly”, who had cognitive impairment (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016, p. 1,490), and who used mobility and sensory aids (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). “Frailty” was therefore viewed as a term that homogenized experiences of aging, and most participants viewed a label of “frail” as problematic. A participant explained:

Frailty is a generalization and I don’t think it has really any place in the medical conversation…the elements that go into making up frailty ought to be discussed, but the generalization of frailty I don’t think is helpful at all (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018, p. 3).

Participants perceived that negative attitudes/assumptions about frailty resulted in de-valuing and undermining persons living with frailty as members of society. A participant described that persons were always, “thinking you weren’t good enough to do something” (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016, p. 1,490).

Across all studies, participants demonstrated strong negative emotions when discussing frailty. Most participants were in agreement that the term “frail” was an unwanted label. A participant cautioned:

I don’t think you should label people as being frail…I wouldn’t want to stigmatise people…[instead] say, you are getting older and you can’t do as much as you perhaps would like to do (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016, p. 1,493).

In some studies, participants explicitly stated that they would avoid using the term “frail” to describe their health, despite being classified as frail by the study authors (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Becker, Reference Becker1994; Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Referring to a person as frail was reported to cause offense, resistance, and strong emotional reactions (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Becker, Reference Becker1994; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). One participant who was not living with frailty fiercely rejected being called “frail”:

I don’t even know what it is like being in bed sick. I have had the flu occasionally but that is not frailty. No, I am definitely not frail, definitely not! (Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009, p. 263).

Only a small subset of participants did not perceive “anything wrong” with the word “frailty” (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018). Overall, participants viewed frailty as a stereotype and as a generalizing label for older adults.

Theme 3: Perceiving impact of frailty language on health and health care utilization

Self-identifying and/or being classified as living with frailty were perceived as having negative impacts such as: decreasing self-esteem, reducing self-perceptions of strength and value, and deteriorating health status (Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Self-identifying and/or adopting the identity of a person with frailty meant to, “incorporate the negative, and feared, views about older people as feeble, dependent and vulnerable” into one’s self-image (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016, p.1,490). Perceiving oneself as frail led to “acting frail”, and was associated with a permanent loss of independence, control, and dignity (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Becker, Reference Becker1994; Escourrou et al., Reference Escourrou, Cesari, Chicoulaa, Fougère, Vellas and Andrieu2017, Reference Escourrou, Herault, Gdoura, Stillmunkés, Oustric and Chicoulaa2019; Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018; Skilbeck et al., Reference Skilbeck, Arthur and Seymour2018; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). Participants vehemently avoided discussing frailty, and 75 per cent of participants perceived themselves as having less frailty than assessed in one study (Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009). One participant explained:

Even though I have a heart problem, I do what I want to do, all my own work and everything…I don’t want to consider myself frail (Grenier, Reference Grenier2007, p. 7).

Diagnosing persons as frail and/or discussing frailty were also perceived as reducing healthy behaviours and health care utilization. A participant explained:

When a physician would say to somebody [that he or she is frail]…would that have any detrimental effect on the individual to start becoming more frail and start acting more frail?… psychologically that seed’s been planted…[the individual may think]: ‘I’m frail so I guess I’m just gonna have to sit in this chair and watch television 24 hours a day’ (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018, p. 4).

Participants perceived that persons who self-identify or who are diagnosed as living with frailty reduce healthy behaviours and their use of health care services amidst the belief that advancing frailty is inevitable and services/activities are not beneficial (Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009). In one study, participants described as not frail/pre-frail reported that they would avoid health care professionals if the topic of frailty/frailty status was introduced (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018). A participant stated, “[I would] get another doctor. I’m dead serious” (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018, p. 4).

The positive consequences of discussing frailty were reported by participants to a lesser extent. Some participants perceived that a diagnosis of living with frailty could serve as motivation, calling attention to their specific vulnerabilities, and encouraging action and the seeking out of health care or support services (Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). However, participants wanted to avoid using the terms “frail”/“frailty” (Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018). Participants described that engaging in behaviours (e.g., following a predictable routine, adjusting expectations of capabilities, and finding ways to manage new impairments) helped them to adapt to changes in health, and were motivated by a desire to maintain health or avoid frailty (Skilbeck et al., Reference Skilbeck, Arthur and Seymour2018). In addition, forming new supportive connections and relationships, “keeping busy”, and maintaining a strong mindset were healthy behaviours that participants used to avoid frailty (Grenier, Reference Grenier2006, Reference Grenier2007). Overall, positive implications for the use of frailty language were described, although participants emphasized potential negative impacts.

In summary, within studies included in this review, frailty was understood as a complex phenomenon or state characterized by inevitable, age-related decline in physical, social, and psychological domains. The term “frail” and the diagnosis of frailty were viewed as generalizing experiences of aging and contributing to stereotypes about older adults. Lastly, self-identifying or being diagnosed as frail was perceived as negatively impacting the health and health care utilization of older adults.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first scoping review to map the breadth of primary studies exploring the meaning and perceptions of frailty language, diagnosis, and perceived implications amongst community-dwelling older adults. In general, frailty is understood as a multidimensional phenomenon with physical, psychological, and social domains. Participants viewed the term “frail”, the use of frailty language, and the diagnosis of frailty as generalizing, reinforcing negative stereotypes, and impacting health and health care utilization.

Gaps in Current Research

The number of studies identified in this scoping review (n = 8) suggests that little research has been completed to explore the perceptions of older adults about frailty language, the meaning of frailty, and the diagnosis of frailty. This is concerning, because research into the science of frailty diagnosis is quickly advancing, and assessing frailty can provide valuable insight into the current and future well-being of older adults (Cosco, Armstrong, Stephan, & Brayne, Reference Cosco, Armstrong, Stephan and Brayne2015; Rolfson et al., Reference Rolfson, Heckman, Bagshaw, Robertson and Hirdes2018). In addition, studies included in this scoping review were from a select number of Western countries, which could be related to both aging trends in these locations, and interest/specializations in frailty research and measures within the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. There may, however, be a gap in research activity surrounding perceptions of frailty in non-Western countries that should be further explored.

If older adults are not included in discussions of frailty, assessments and services may not align with older adults’ preferred language or priorities, which will lead to limited interest and uptake. Older adults are often excluded from participating in studies because of barriers such as lack of access to transportation, reduced cognitive function, and immobility (Kirkland & The OA-Involve Team, Reference Kirkland2017; Velzke & Baumann, Reference Velzke and Baumann2017). However, citizen engagement in research is essential, and tools/guidelines exist to support the inclusion of older adults as stakeholders (Kirkland & The OA-Involve Team, Reference Kirkland2017). Ultimately, the development of acceptable interventions and the uptake of services are facilitated by the inclusion of older adults in research (Doolan-Noble, Mehta, Waters, & Baxter, Reference Doolan-Noble, Mehta, Waters and Baxter2019; Kirkland The OA-Involve Team, Reference Kirkland2017; Velzke & Baumann, Reference Velzke and Baumann2017).

Attention to the Social Domain of Frailty

Participants across studies consistently described frailty as having social and psychological domains and viewed psychosocial symptoms as potent indicators of frailty. Despite this, the tools used to assess frailty primarily sample the physical domain (Fried et al., Reference Fried, Tangen, Walston, Newman, Hirsch and Gottdiener2001; Rockwood & Mitnitski, Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2011), and negate important symptoms of social frailty (e.g., lack of social support in the home (Cesari, Reference Cesari2019). Similar reports of frailty assessment being solely based on physical criteria have been described in clinical practice and research settings (Sutton et al., Reference Sutton, Gould, Daley, Coulson, Ward and Butler2016).

Despite limited sampling of the psychosocial aspects of frailty in measurement tools, participants’ experiences and the perceived importance of social frailty in our study support a conceptual model of social frailty (Bunt, Steverink, Olthof, van der Schans, & Hobbelen, Reference Bunt, Steverink, Olthof, van der Schans and Hobbelen2017). Social frailty is defined as a “continuum of being at risk of losing or having lost resources to fulfill social needs” (Bunt et al., Reference Bunt, Steverink, Olthof, van der Schans and Hobbelen2017, p. 323). Factors described as contributing to needs fulfillment including social or general resources, social behaviours and activities, and self-management abilities, are likely indicators of social frailty that should be assessed in frailty tools (Bunt et al., Reference Bunt, Steverink, Olthof, van der Schans and Hobbelen2017). The recently published Fit-Frail Scale (Theou et al., Reference Theou, Andrew, Surian Ahip, Squires, McGarrigle and Blodgett2019) samples social and psychological aspects of frailty, and may be a holistic measure of frailty.

Critical Perceptions of Language and Social Meaning

Culturally specific understandings of frailty were also demonstrated in our study findings and should be further explored. Variations exist in linguistic equivalencies, as revealed in the Puts et al. (Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009) article; the word “frailty” does not exist in the Dutch language, therefore, terms such as “vulnerability” and “fragility” are used instead. In fact, several languages have variations of the term, which can be accompanied by slight differences in meaning (Grenier, Reference Grenier2007). Interestingly, in French-speaking Québec, frailty has been discussed as perte d’autonomie or loss of autonomy, and not as frêle, which would be the direct translation (Grenier, Reference Grenier2007). Overall, these subtle differences highlight the tendency for frailty to be conceptualized as a negative experience, and demonstrate how easily it is associated with loss, regardless of linguistic or cultural variations.

The primarily negative perceptions of frailty in this review contrast with other research findings in which older people perceived as having frailty were also able to, “enjoy positive aspects of embodiment and maintain objective strengths” (Pickard, Reference Pickard2018, p. 25). This may in part be the result of differing perceptions of aging in different cultures. However, negative connotations and understandings of a designation of frailty reported in this review are similar to findings reported in disability studies, in which social forces are perceived as highlighting fragility and vulnerability in the experiences of persons with disabilities, rather than deconstructing or challenging stereotypes (Burghardt, Reference Burghardt2013). Therefore, additional research on how to positively influence society’s shared views of aging and frailty is needed, along with a critical examination of the unintended effects of frailty language and diagnosis (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Cluley, Danely, Laceulle, Leon-Salas and Vanhoutte2019).

Frailty as an Imposed Label

It is evident from this review that the term “frailty” is perceived as a label most often imposed on older adults by others, usually by health care professionals. Frailty is similarly described as an imposed identity and label by Higgs and Gilleard (Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014), who state that frailty “is made manifest through third party actions, not through first person accounts” (p. 15). Although effort is being made to use person-first language in frailty research, the term itself remains a powerful designation that may serve to “other” persons classified as frail and reinforces a negative social image of the later stages of life (i.e., older adulthood) (Gilleard & Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010; Higgs & Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014). Some scholars have argued that frailty is a socially constructed label that is imposed on older adults (Gilleard & Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010), highlighting the need to explore societal understandings of later life and the effect that these perspectives can have on older adults’ experiences, especially those who are diagnosed or classified as living with frailty. Hence, persons perceived as frail may be symbolically reduced to a frailty label, and the diversity in aging experiences that exists may be overlooked (Grenier, Lloyd, & Phillipson, Reference Grenier, Lloyd and Phillipson2017).

Based on the results of this review, older adults do not, in general, identify with the imposed identity or diagnosis of living with frailty. Furthermore, a classification of “living with frailty” is perceived as having harmful implications, including the avoidance of health care services that aim to support independence and well-being. This raises the question as to whether new terminology is required, or whether a more holistic perspective of the changes that can accompany aging is needed. The World Report on Ageing and Health (World Health Organization, 2015) uses the term “intrinsic capacity” when discussing the potential for healthy aging, in terms of individuals’ physical and cognitive health and overall functional ability, and the ongoing influence of the social environment. Such conceptualizations of the aging experience, which are less deficit focused and which positively support older adults in their health in ways that are meaningful to them, are increasingly being called for (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Cluley, Danely, Laceulle, Leon-Salas and Vanhoutte2019). Importantly, exploring, engaging, and valuing older adults in the discourse on frailty does not require setting “aside the progress made in a formal quantitative understanding of frailty in order to engage in a debate about semantics” (Rockwood & Howlett, Reference Rockwood and Howlett2018, p.3). Instead, researchers in diverse disciplines (e.g., gerontology, law) need to simultaneously explore the semantics or meaning attributed to the term “frailty” and inform the use of language by persons seeking to measure frailty (Grenier, Reference Grenier2019).

Recommendations

Overall, recommendations based on this review propose that health care professionals and researchers should:(1) employ a holistic view and understand frailty as a multidimensional concept, (2) use person-first language and discuss elements of frailty, and (3) use a strengths-based approach.

Employ a holistic view of frailty

The definition of frailty has shifted from purely physical criteria to a more comprehensive or holistic view of the individual to include psychosocial and environmental constructs. It is recommended that we further explore the social determinants of health (e.g., housing, financial status, social support, culture, education) during a comprehensive assessment and sensitive discussion of frailty (Grenier, Reference Grenier2007), and seek interdisciplinary training and education in holistic models of care to expand perspectives of frailty (and all diagnoses) beyond a biomedical model (Coker, Martin, Simpson, & Lafortune, Reference Coker, Martin, Simpson and Lafortune2019; Gustafsson, Edberg, & Dahlin-Ivanoff, Reference Gustafsson, Edberg and Dahlin-Ivanoff2012; Levy, Reference Levy2018). The Positive Education about Aging and Contact Experiences (PEACE) model, for example, may be an effective training program to improve attitudes about aging in health care professionals (Levy, Reference Levy2018).

Use person-first language and discuss elements of frailty

One should use language such as “a person living with frailty” to emphasize personhood and avoid replacing a person with a diagnosis (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Lawless et al., Reference Lawless, Archibald, Ambagtsheer and Kitson2020; Puts et al., Reference Puts, Shekary, Widdershoven, Heldens and Deeg2009) and should acknowledge and value the individual, unique identities of older adults to provide high-quality care and build trusting relationships (Becker, Reference Becker1994). One should communicate with older adults about individual, specific health challenges or age-related changes, rather than using the term “frail” as an all-encompassing description of health, and assess communication and language preferences by asking, “what words do you use to talk about your health?” (Brooks, Ballinger, Nutbeam, & Adams, Reference Brooks, Ballinger, Nutbeam and Adams2017; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016). One should also educate older adults to understand that “frailty is a dynamic, reversible and avoidable state”, and share examples of persons living with aspects of frailty to promote acceptance of the term (Age UK, British Geriatrics Society, 2015; Schoenborn et al., Reference Schoenborn, Rasmussen, Xue, Walston, McAdams-Demarco and Segev2018). For example, one could describe “a person who doesn’t leave the house as much as they would like” or “who doesn’t see friends/family very often” as persons who have aspects of frailty in the social domain.

Use a strengths-based approach

When discussing symptoms of frailty or vulnerability in one domain, one should focus on the person’s strengths in another domain (Grenier, Reference Grenier2006; Warmoth, Lang, et al., Reference Warmoth, Lang, Phoenix, Abraham, Andrew and Hubbard2016) and assess the strengths and abilities of the person to develop interventions that can facilitate independence while acknowledging areas of frailty and risk, rather than focusing on deficits (Minimol, Reference Minimol2016). For example, it would be good to ask “what do you think your strengths are” and validate strengths by stating, “you have a very strong mind, family support system, faith or physique. Let’s focus together on using your many strengths to manage the health changes you are experiencing.” In addition, one should outline effective treatments and coping strategies to live with/avoid frailty (Dury et al., Reference Dury, Dierckx, Van Der Vorst, Van der Elst, Fret and Duppen2018).

Limitations

Unpublished and non-English-language articles were not included in this review and relevant studies that were excluded may have influenced our study findings. Within some databases (i.e., CINAHL), use of the keyword “frail” limited search results; however, concurrent searches in other databases and hand searches supported the comprehensiveness of the search. The protocol and findings from this review were not registered in a review database because of the iterative nature and timeline of this project, but comprehensive search was reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow2021).

Conclusion

Overall, critical work has been done in operationalizing and quantifying frailty, and people often live with frailty as they age. Therefore, the use of the term cannot be dismissed in clinical practice and research. However, ongoing examination of the term “frailty”, and guidelines for language are needed. Findings from this review can inform next steps in frailty research and help researchers/professionals to avoid the inadvertent stigmatization of older adults. Most importantly, this review highlights the need to include older adults in conversations about frailty.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for funding from grants and scholarships from Alzheimer Society of Canada Brant, Haldimand-Norfolk, Hamilton-Halton Branch; Canadian Frailty Network Interdisciplinary Fellowship 2018–19; Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant number 159269; Canadian Nurses Foundation; Labarge Post-Doctoral Fellowship for Mobility in Aging 2019–20; and Registered Nurses Foundation of Ontario, Mental Health Interest Group.