The ongoing debate regarding appropriate nomenclature to describe health care users has been recently highlighted again in the medical literature (Reference Neuberger and TallisNeuberger & Tallis, 1999), principally involving the appropriateness of the terms patient and client.

Those objecting to the term patient do so for a variety of reasons. They argue that both the derivation of patient (patiens - to suffer or bear) and modern usage imply an unequal relationship, label people as ill and do not allow the sufferer to demonstrate responsibility in maintaining their own health (Reference Neuberger and TallisNeuberger & Tallis, 1999). However, etymological and semantic criticism applies equally to the word client, derived from Latin (cliens) and meaning “one who is obliged to make supplications to a powerful figure for material assistance” (Reference GeorgeGeorge, 1998). Supporters of the term patient argue that the term client lacks the compassion and trust inherent within the relationships between the sick and their carers (Reference Neuberger and TallisNeuberger & Tallis, 1999). There are few published studies to inform this debate (Reference Upton, Harm-Boer and NealeUpton et al, 1994; Reference NairNair, 1998) and these do not examine preferences across a comprehensive range of demographic variables. Furthermore, neither study assessed the attitudes of health care users to the terms patient and client.

The use of the term client is particularly prevalent in psychiatric settings, especially among non-medical staff. In the current climate of evidence-based practice there is little critical support for its use. The aim of the present study was to determine the preference for, and attitudes to, the terms patient and client in individuals attending a psychiatric out-patient clinic.

Subjects

The study was conducted in the psychiatric out-patient department of an NHS inner London teaching hospital over a 2-week period after ethical approval was obtained. The clinic predominantly manages general adult psychiatric problems, although those attending the specialist eating disorders and sexual disorders clinics were also included in this study. The old age and child psychiatry clinics are conducted elsewhere and, therefore, elderly people and children are not included in this sample. All those who had appointments over the 2-week period were eligible for inclusion in the study.

Method

Data were gathered from a self-administered questionnaire and the subjects' case-notes. The questionnaire determined subject preferences to three choices of term (patient, client or other), their attitudes (to patient and client using a five-point Likert scale) and socio-demographic and psychiatric data (Table 1). Subjects were also asked to comment on their choice of term. Missing data and diagnostic data for both the sampled and non-sampled individuals were captured from their case notes by the investigators. Social class was derived from occupation using standard criteria (Department of Health, 1996).

Table 1. Frequencies of choice of term patient or client by demographic and diagnostic variables

| Variable | Patient n (%) | Client n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 51 (77) | 15 (23) |

| Female | 52 (76) | 16 (24) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 39.54 | 35.85 |

| In-patient treatment | ||

| Previous admission | 53 (70)* | 23 (30)* |

| No previous admission | 50 (86) | 8 (14) |

| Mental Health Act status | ||

| Involuntary in-patients | 9 (69) | 4 (31) |

| Voluntary patients | 44 (70) | 19 (30) |

| Doctor's grade | ||

| Professor | 7 (70) | 3 (30) |

| Consultant | 24 (82) | 5 (18) |

| Senior registrar | 23 (77) | 7 (23) |

| Registrar | 17 (77) | 5 (23) |

| Senior house officer | 32 (80) | 8 (20) |

| Time patient | ||

| < 1 month | 13 (76) | 4 (24) |

| 1 month to 1 year | 29 (78) | 8 (22) |

| 1 year to 5 years | 28 (80) | 7 (20) |

| > 5 years | 27 (75) | 9 (25) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Depression | 33 (92) | 3 (8) |

| Schizophrenia | 16 (76) | 5 (24) |

| Psychosexual | 13 (76) | 4 (24) |

| Eating disorder | 12 (75) | 4 (25) |

| Bipolar disorder | 12 (80) | 3 (20) |

| Other | 10 (58) | 7 (42) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White UK | 67 (79) | 18 (21) |

| White Irish | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

| White other | 15 (71) | 6 (29) |

| All other | 10 (59) | 7 (41) |

| Social class (occupation) | ||

| I | 11 (92) | 1 (8) |

| II | 17 (74) | 6 (26) |

| III | 27 (80) | 8 (20) |

| IV | 17 (71) | 7 (29) |

| V | 16 (89) | 2 (11) |

| Student | 4 (67) | 2 (33) |

| Employed | ||

| Yes | 35 (78) | 10 (22) |

| No | 65 (76) | 20 (24) |

| Retired | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

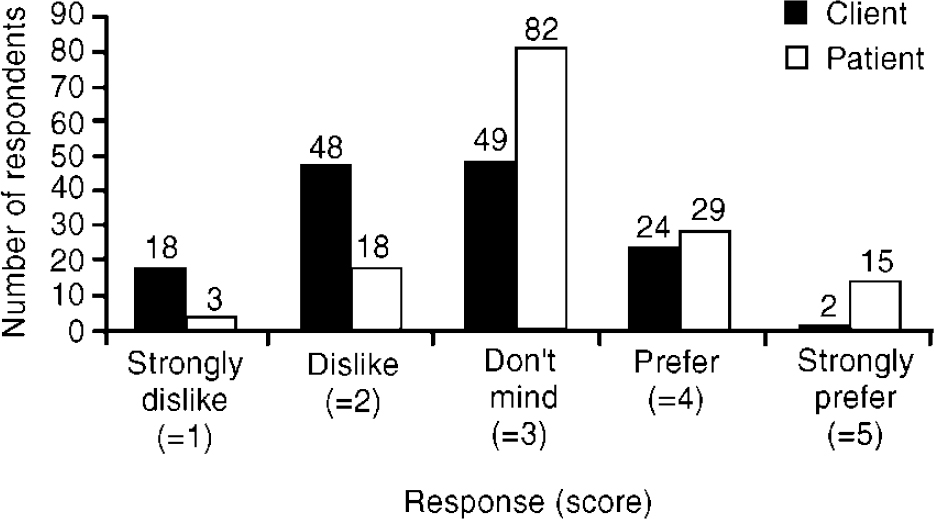

The Likert scales, which asked for the individual's attitude to the terms patient and client, were scored from ‘strongly dislike’ (one) to ‘strongly prefer’ (five). In an attempt to minimise the ‘halo’ effect, the clinic reception staff distributed and received back the questionnaires prior to the appointment. The study was identified as being coordinated by the hospital, not by the medical staff.

Results were analysed using the independent sample t-test for continuous variables (including mean scores from the Likert scales) and chi-squared for categorical data. In the comparison of preference for terms those who listed ‘other’ had their data excluded from the analysis.

Results

Attendance

During the study period 314 people had appointments, of which 184 (59%) attended. Of the attendees, 147 (80%) completed the questionnaire, 32 (17%) were erroneously not given questionnaires by the reception staff and five (3%) refused.

Preference of terms

Of those who expressed a preference for either patient or client (96%), the majority preferred the term patient (77% patient, 23% client). This did not vary significantly by socio-demographic grouping or psychiatric diagnosis, other than an increased majority in favour of the term patient was stated by subjects who had never been inpatients (P=0.02) (Table 1).

Attitudes

Forty-seven per cent of the sample either ‘disliked’ or ‘strongly disliked’ the term client and 14% felt the same way about the term patient. Moreover, only 1% ‘strongly preferred’ the term client and 10% the term patient (Fig. 1). The mean score derived from the Likert scale was significantly lower for the term client (2.60) than patient (3.24; P<0.001), demonstrating much greater antipathy towards the term client.

Fig. 1. Number of respondents by attitudes towards terms patient and client

Particular groups demonstrated significantly different strength of feeling towards one or other term. Men and people over the age of 40 demonstrated a significantly more positive attitude towards the term patient than younger people and women. Moreover, a diagnosis of depression, White UK ethnicity and never having had an in-patient stay were associated with significantly greater antipathy towards the term client than the remainder of the sample in each of these variables (Table 2). There was, however, no group that showed a positive attitude towards the term client.

Table 2. Attitudes to the terms patient and client derived from Likert scales

| Attitude to terms | Means | Means | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Patient | 3.37 | 3.06 | 0.28 (0.002 to 0.56) | 0.049 |

| Client | 2.54 | 2.65 | -0.11 (-0.43 to 0.21) | 0.508 |

| Age <40 | Age >40 | |||

| Patient | 3.10 | 3.44 | 0 34 (0.0 to 0.62) | 0.024 |

| Client | 2.69 | 2.42 | 0.27 (-0.65 to 0.59) | 0.115 |

| Previous in-patient | Never in-patient | |||

| Patient | 3.19 | 3.30 | -0.12 (-0.40 to 0.17) | 0.43 |

| Client | 2.77 | 2.36 | 0.41 (0.09 to 0.73) | 0.012 |

| White | Non-white | |||

| Patient | 3.32 | 3.09 | 0.23 (-0.06 to 0.52) | 0.123 |

| Client | 2.47 | 2.82 | 0.35 (0.03 to 0.68) | 0.034 |

| Depression | Non-depression | |||

| Patient | 3.25 | 3.27 | -0.02 (-0.35 to 0.31) | 0.9 |

| Client | 2.21 | 2.68 | 0.47 (0.12 to 0.84) | 0.006 |

| Patient | Client | |||

| Total sample (mean) | 3.24 | 2.60 | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.85) | <0.001 |

Non-sampled v. sampled subjects

People previously admitted involuntarily were less likely to attend their appointment (P<0.001). However, former involuntary patients who did attend chose terms at similar rates to former voluntary in-patients and demonstrated similar attitudes to the two terms. There were no other significant differences between those sampled and those not sampled.

Discussion

Our study is the first systematically to measure attitudes to the terms patient and client in a psychiatric out-patient setting and compare rates of choice across standard socio-demographic and psychiatric variables. The majority of subjects chose the term patient irrespective of how they were grouped. Further, the term client was disliked by almost half of those sampled, whereas there was little antipathy towards the term patient. No group had a positive attitude towards the term client.

In everyday usage the term patient is associated with a traditional relationship with a doctor, and client with a business relationship. The semantics of the term have been discussed already. The relationship between health care provider and the individual they care for is extremely complex, although an individual's preference for term of address does provide some insights into our understanding of this relationship.

The observation in our study that people over the age of 40 had a greater liking for the term patient may reflect their wish to retain traditional terminology to describe their relationship with their hospital. Furthermore, the dislike of the term client by those who are depressed may indicate a resistance to a term that lacks compassion and connotations of care. The relative acceptance of the term client by those who have had psychiatric in-patient stays may be a result of their exposure and subsequent adjustment to the term because it is commonly used by non-medical in-patient staff. It is harder to explain why men show stronger liking for the term patient than women do, and why those from a White UK background show stronger dislike for the term client.

Pimlot's introduction to Nineteen Eighty-Four in reference to ‘Newspeak’ suggested,

“Orwell was making an observation that is as relevant to the behaviour of petty bureaucrats as of dictators, when he noted the eagerness with which truth evaders shy away from well-known words and substitute their own.” (Reference Pimlott and OrwellPimlott, 1989)

According to our research, the substitution of the term client for patient has little support from the user's perspective. We feel that those who argue that the term client is empowering should demonstrate consistency with this perspective, respect the opinion of their ‘clients’ and return to using the term patient. Advocating alternative terminology in a psychiatric setting, despite the above evidence, demands reflection upon the source of one's objection to the clearly expressed, preferred appellation of patients.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.