INTRODUCTION

This article studies the involvement of consular personnel in the “coolie trade”, a crucial subject in our understanding of the development of an exploitative migratory system in nineteenth-century southeast China.Footnote 1 I will focus on Spanish representatives as an extreme case study of the wider role of consuls as middlemen in this human trafficking. Authors writing about the history of the coolie trade have mostly focused on the experiences of immigrants and the diplomatic dispute between major Western powers, mainly the British, French, American, and Portuguese.Footnote 2 However, a large percentage of the coolie trade responded to private Spanish demand, as Cuba, one of the major destinations of the trafficking, was a Spanish colony sustained by sugar cane production. Sino-Spanish relations were therefore decisive to Pacific trade and transnational migration.Footnote 3 The participation of Spanish middlemen provides an excellent case study of the complex entanglements between different forms of private and state-based imperial capitalistic business. This article aims to gain more comprehensive insight into this complex phenomenon.

Following the opening of China's first Spanish consulate in Macao in 1852, Spain quickly had consulates in every Chinese treaty port, even though it was a peripheral power with no colonial concessions in China. Spain's moderately widespread consular deployment along China's southern coast is intriguing, as it was a Western nation in crisis and the presence of Spaniards in treaty ports was meagre in comparison to other Western powers. Spain's principal transnational reach in the second half of the nineteenth century had to do with its two principal colonies, Cuba and the Philippines, which were both economically and politically unstable. Cuba's sugar cane complexes depended greatly on the supply of vast and cheap labour, and in the 1850s and 1860s Chinese indenture reinforced the established African slave labour.

With the pressure of the abolitionist movement from the second half of the nineteenth century, and the subsequent increasing cost of slaves, agricultural producers in Cuba began looking for a supplement to African slave labour. They found it in the form of Chinese indentured contract labourers, who became of prime importance to the Cuban economy.Footnote 4 Between 1847 and 1874, about 125,000 Chinese men were taken to Havana through a transnational mass-migration business venture, to work mostly on sugar cane plantations, providing reinforcements to African labour while slavery was being “gradually abolished”.

The recruiting process, transport settings, and working conditions of Chinese emigrant workers were highly abusive. Chinese crimps received a “capitation fee” – an emolument for every emigrant recruited – and as availability of volunteer emigrants diminished, the price per worker also increased. Crimps’ thirst for revenue hardened recruiting methods. Thus, prospective emigrants were often deceived using fake promises of good wages and fair working conditions in a rich foreign land, bound to emigrating as payment for debts, and sometimes kidnapped and tortured until they signed up. They were then gathered and locked into guarded receiving stations until embarkation. Moreover, the contracts they signed bound them to eight years of servitude from which they could seldom escape. Transport, food, clothing, agency, passport, legalizations, and other fees were advanced to the emigrant, who accumulated a debt to pay back from future earnings, thus becoming indebted for years and being forced to renew contracts upon expiration.

Chinese emigrants were transported in overcrowded vessels and in dehumanizing settings, where the average death rates on board were high – twenty-five or thirty per cent, and sixteen per cent for Cuba. The consuls and vice-consuls studied covered up vessel overcrowding, rushed the departure of vessels in unfit travelling conditions, and overlooked emigrants’ petitions to disembark. Once in the place of destination, they were exploited in conditions that bore parallelisms with slavery. In the Cuban case, they were confined in the same way – and even together – as slaves, and using the same methods of physical control, such as shackles, traps, whippings, and lockups. This mistreatment triggered international condemnation, and in 1874 the Chinese government put a halt to the traffic after a multinational commission, led by Chen Lanbin, travelled to Cuba and issued a disturbing report on the mistreatment of Chinese workers.Footnote 5

Spanish consular officers were often involved in the shipping of unwilling emigrants and were keen on establishing a migration export monopoly, despite the human costs. Their pecuniary activities are one crucial key to why Chinese immigration to Latin America became a dehumanized trading business. Particularly, their participation sheds new light on why emigrants who had denounced kidnapping or deceitful recruitment still signed their contracts and did not speak out when asked whether they emigrated voluntarily.Footnote 6 José Luis Luzón, Florentino Rodao, and Luis Eugenio Togores have studied this connection in two papers, the first one published in 1989, and the second one, co-authored, in 1990.Footnote 7 These three authors correctly point to Chinese emigration to the Caribbean as Spain's main business in China between the 1850s and 1874, and associate some Spanish representatives with unethical activities of mass migration.Footnote 8 In this article, I argue that the Spanish consular presence in Chinese treaty ports went hand in hand with Spanish interests in the coolie trade business, not only as part of Spain's colonial capitalistic ambitions to satisfy Cuban demand for cheap labour, but also – and especially – due to consular officers’ private, individual interests. Extensively, the involvement of Spanish consular officers in the trade was key to sustaining brutalizing human trafficking, as they used their position of authority to commit illegalities so as to attain a monopoly over the trade.

This paper's main contribution is the application of the concept of merchant-consul to the history of the trade in Chinese immigrants to America. This type of figure, not yet considered in this historical context, enjoyed a hybrid role, looking after their own pecuniary interests while simultaneously having to satisfy Spanish commercial objectives. Although, at least by the 1880s, it was illegal for Spanish consuls to become merchants or undertake any professional activity in their country of residence, it is clear that, in China, they engaged directly in this human trade.Footnote 9

However, consular officers are only one type of inconspicuous figure in a long list of middlemen, such as brokers, recruiting agents, companies, and local authorities, who benefitted from this trafficking and were crucial to the history of Chinese immigration. Adam McKeown tackled the mechanisms operating behind Asian migration in his work on border control and the changing perceptions of brokers across time.Footnote 10 The role of consular staff and official representatives in the migratory system is particularly relevant, as every Chinese citizen in the process of emigrating had to go through consular control. In the case of the harbour of Xiamen (also called Amoy), Douglas Fix and Ei Murakami have recently portrayed the processes of recruiting and transporting labourers, although focusing mainly on the work of agents, companies, and brokers. While Fix puts emphasis on the network formed by brokers, crimps, and emigration houses, Murakami argues that Chinese brokers were crucial in the development of an abusive system.Footnote 11 Although in this article I intend to highlight the role of consuls in the recruiting process, further research should be done regarding other silenced middlemen, particularly in Macao and Shantou.

Using mainly unpublished primary sources preserved at the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Spain, I will determine the extent of Spanish consular involvement in the coolie trade and consider its role in sustaining the mistreatment of Chinese immigrants throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. With some exceptions, and in spite of their vast amount, richness, and paramount relevance, Spanish primary sources have been used rather infrequently in the study of the coolie trade, in contrast to US and British correspondence.Footnote 12 I focus on the first years of consular deployment in China, the 1850s, a period that coincides with the strongest flow of Chinese immigrants to Cuba.

In this article, I present labour migration as a sequence in the industrialized plantation system, which also served as a commercialized source of profit in itself. To do so, I add a third concept to McKeown's analysis of the commodification of labour. I show how, besides labour in relation to slavery and labour as service, labour was also a commercialized item within the industrialized plantation mechanism.Footnote 13 Middlemen such as consuls, benefitting from the transit of Chinese labourers in the transnational migratory macrostructure, turned potential sources of labour – coolies – into marketable items. Chinese indentured labour immigration can, therefore, be considered a commodity, not only because it developed from a system of servitude, both in China and in Cuba, but also because it was part of an industrialized plantation system with global implications.Footnote 14

Spain, like other peripheral Western nations in China such as the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, and Sweden, played a minor role in the colonial enterprise. However, this article shows how exploitation and capitalism could still develop at the hand of a peripheral power in decadence, like Spain, outside of the colonizer-colonized dichotomy dominant in late-Qing history.Footnote 15 It was Spain's lack of a treaty with China until 1864 that most probably favoured the development of irregular activities like this human trafficking, because it meant that the country could enter into less regularized relations than other Western powers.

Consular personnel had a significant role in the globalization of capitalism in the nineteenth century. This early case of consular deployment shows how, beyond being intermediaries, the actions of consuls affected the course of transnational trade, as they defended personal enterprises and national strategies against powerful nations.Footnote 16 Their capitalist drive was such as to overlook any abuses committed in the recruitment, treatment, and transport of emigrant labourers. They even competed ferociously with their own peers in the Spanish consular web to be the sole beneficiaries of the emoluments attached to contract legalizations, issuing of passports, ship duties, and tax fees. The role of consuls as middlemen in the trafficking of Chinese indentured labourers is illustrative of the intra-imperial and international dynamics that came into play in treaty-port China.

However, not only consuls, but also the Spanish Minister Plenipotentiary Sinibald de Mas (Figure 1) himself became indirectly associated with the trade by pressuring the emigration of more than 15,000 Chinese workers to Cuba between 1866 and 1867. Though Mas's primary goal in China was signing the Sino-Spanish Treaty, his late involvement in the trade as the state's representative supports the idea that the trafficking of labourers was also at the top of the Spanish government's list of interests in China.Footnote 17 Conversely, Mas, who arrived in China for the first time in 1844 and therefore preceded the first consuls, had little knowledge of the intricacies of Chinese immigration to Cuba until 1865.Footnote 18 Mas's late association with the trade had to do with the different nature of consulates and legations in the nineteenth century. While the objectives of consular personnel were to enhance commercial relations with the country of their post – in this case, Spanish trade with the Philippines and the export of Chinese emigrant workers to Cuba – the legation was responsible for diplomatic relations.Footnote 19 This explains why the trafficking of Chinese workers to America had a remarkable place in consular reports in the 1850s and 1860s, whereas Mas's principal concern was signing the Sino-Spanish Treaty. After the 1864 Sino-Spanish Treaty, consuls’ actions lost clarity and particularity, especially after the later 1877 Treaty, when the Qing government imposed a final stop to the coolie trade to Cuba.Footnote 20

Figure 1. Portrait of Sinibald de Mas, by Tomàs Moragas i Torras, 1882.

© Arxiu Fotogràfic Centre Excursionista de Catalunya.

To address these issues, I will first draw on the system of consulates in China after the Nanjing Treaty and the specificities of the Spanish case. I will then move on to analysing how the direct aim of the first Spanish consular employees in China was to control the profits of the coolie trade. Finally, I will portray these consuls’ role in the long-debated issue regarding contradictory sources about kidnapping and involuntary embarking.

THE CONSULAR SYSTEM IN TREATY-PORT CHINA

The Western consular deployment in China began in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanjing, which gave Great Britain the right to establish superintendents and consular officials in each one of the five treaty ports opened to international commerce, that is Guangzhou, Shanghai, Ningbo, Xiamen, and Fuzhou. The year after, with the British Supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, which broadened the scope of and ratified the previous one, the privilege of extraterritoriality to British subjects was added, a privilege that the Americans and French also enjoyed with their respective treaties of 1844 and 1845.Footnote 21

The first Spanish consulate in China became operative in Macao in 1853, with Nicasio Cañete y Moral occupying the position of Consul General. Until then, consuls from other nations, mostly British, had acted as representatives for foreign merchants whose nation did not yet have consular representation. As most foreign merchants did not have representatives of their own countries in China, they often had no other option than to head to British consuls for official procedures. However, British consuls did not have the necessary jurisdiction to attend to the legal matters of citizens from other countries. Henry Pottinger, then British Plenipotentiary in China, removed this practice and, as a result, other countries named British merchants established in China as vice-consuls for their nations, which became common practice a few years after the Treaty of Nanjing.Footnote 22

In 1856, Spain had four foreign vice-consuls in Chinese treaty ports, three probably British, and one with a Portuguese surname. The majority of them were merchants, had no salary, and often used their positions to better their “not always lawful” private businesses. Their main role was to arrange the necessary paperwork related to the embarkation and disembarkation of goods in Spanish vessels before the port authorities.Footnote 23 The wait for treaties and difficulties to find consular personnel for China were surely behind resorting to merchant-consuls for many nations, something which was not uncommon.Footnote 24 Even Pottinger had struggled to find staff for British consulates after the opening of the five treaty ports. Most of them ended up being recruited from the Foreign Office, and had no consular or diplomatic experience.Footnote 25 In the Spanish case, this led to the recruitment of unprofessional consular personnel.

After Macao, the next Spanish consulates to open were Shanghai (1858) and Xiamen (1859), the latter – together with Macao – being a hotspot for the trafficking of Chinese emigrants (Figure 2). Hong Kong and Fuzhou followed in 1863, and Guangzhou and Ningbo in 1864. Shantou (also called Swatow) – another key harbour in the coolie trade – did not have a consulate until 1869, as it was not a treaty port. However, various Spanish consular agents were assigned positions there before 1869 to attend to Spanish business interests in emigrant trafficking. This might be at the root of the coolie trade developing out of control, as Spaniards had no jurisdiction there and could act more freely than in regulated treaty ports.

Figure 2. Many buildings at Xiamen's harbour (also known as Amoy) faced over the waterfront.

“The Anchor of Amoy”, W. Tyrone Power, Recollections of a Three Years' Residence in China: Including Peregrinations in Spain, Morocco, Egypt, India, Australia, and New Zealand (Bentley, 1853).

Xiamen was one of the main emigration hubs until the trade decreased there in 1858.Footnote 26 It was in Xiamen where the first riot against Westerners regarding the abuses connected to the coolie trade took place in 1852.Footnote 27 This event temporarily halted the trade, shifted a great part of the trade to Namoa, an island near the port of Shantou, and affected British attitudes towards the way emigration was being handled. Until then, emigrants had been leaving that port for various destinations in America and Australia.

Tait & Company and Syme, Muir & Company were the main companies operating this traffic in Xiamen. To do so, they opened customhouses known as barracoons – a term derived from the barracks used to lodge slaves in the African slave trade – to gather emigrants before departure.Footnote 28 Tait & Company's barracoon was a floating receiving station, the Emigrant, situated in front of the harbour of Xiamen. Chinese crimps, or ketou “brokers”, recruited prospective emigrant labourers – often using all sorts of deceptive means and abuses – and retained them in these structures to await departure.

When the trade became increasingly more difficult to operate in Xiamen, the bulk of emigration turned progressively to Shantou and Macao, especially from 1857, although it continued on a small scale, at least, until 1869. This contradicts the data provided by Meagher – according to which, the trade in Xiamen had ended by 1866 – and strengthens Fix's argument that after 1866 Xiamen became “a small-scale provider of recruits in the Chinese coolie trade now based in Macao and Shantou by early 1867”.Footnote 29

A case that illustrates how Xiamen was still engaged in the trade in the late 1860s is Xiamen Consul Tiburcio Faraldo's intentions to establish a commercial house with agent Mariano del Piélago. In 1869, Faraldo asked local governor Daotai Zeng for permission to open an emigration office on behalf of Spanish merchant Piélago, who had been dispatching Chinese emigrants to Manila and to Havana since the 1850s, and who, at that time, was agent for the Cuban company Merino Gilledo y Cª. The Spanish merchant had been at the centre of reports accusing him of irregularities and of buying kidnapped emigrants for shipment to Cuba. Despite these reports, Piélago's ships, Macao and Villa de Comillas, departed for Cuba with 400 and 290 emigrants each. US Consul Le Gendre pointed to Faraldo's threats to the Daotai and to the Spanish consul's economic interest to ensure the shipment.Footnote 30

While this was taking place in Xiamen, Spain obtained permanent diplomatic representation in Beijing with the signing of the Sino-Spanish Treaty in 1864, becoming the fourth nation to enjoy this right, after Great Britain, France, and Russia. Sinibald de Mas took up residence in the capital, and in 1867 he established the Legation there. During the second half of the nineteenth century, Spain's diplomatic objective was to further Spanish commercial relations along China's coast, particularly between the Philippines and China. For this reason, their political approach was always neutral and non-interventionist. However, in the 1870s, after the 1864 Treaty, there were significant frictions between the Qing government and Spanish diplomats in China with regard to the circumstances of Chinese indentured labour in Cuba, until it was officially put to an end with the signing of the second treaty in 1877.Footnote 31

Unlike diplomats, consular officers were not active in this kind of negotiation, as they were not representatives for their nation; therefore, their responsibilities were not political, but technical, and only reduced to a limited area in the country of residence. The functions and obligations of Spanish consular offices, no matter their destination, were mainly attending to the needs of Spanish citizens, protecting their interests, giving them access to the Spanish legal framework, as well as reporting to the Legation on any political event taking place in the territory of their domain. While the main objective of the diplomatic mission in China was signing the treaty, consuls’ responsibility was more discontinuous and imprecise, probably because of the instability of their posts. In general, their main activities were also concerned with enhancing commercial relations between China and the Philippines, as well as supervising the embarkation of Chinese citizens to Spanish colonies.Footnote 32

Corruption was recurrent in Spanish consulates in China, especially regarding the organization of emigrant traffic to Spanish colonies, and went on well into the twentieth century.Footnote 33 For instance, dispatching Chinese emigrants to the other Spanish colony at that time, the Philippines, was also an important economic resource for the Xiamen consulate, which used to charge extra fees to emigrants, well after the official halt of Chinese emigration to Cuba in 1874.Footnote 34 Ethical deficiency in the Spanish consular and diplomatic corps was not limited to nineteenth-century China. In the first third of the twentieth century, the first assistant secretary of the Ministry of State, Francisco Agramonte y Cortijo, was still fiercely critical of the general lack of morals and professionalism of Spanish diplomats abroad.Footnote 35

As foreign consuls took on responsibilities regarding the supervision of their nation's commercial relations, they were quickly caught in commercial and legal disputes regarding the activities of Western merchants and companies in the trade in opium and the export of Chinese indentured labourers from 1847. Either the distance to the metropolis or the geopolitical and historical context, where they had to deal tactfully with Qing central and provincial authorities, gave them a certain autonomy over their nation's state. These conflicts particularly materialized in the onset of and throughout the Second Opium War (1856–1860).Footnote 36

FIGHTING OVER EMIGRANTS’ FEES: INTRA-CONSULAR DISPUTES

Spanish consular personnel in China were involved in the coolie trade from the establishment of the first vice-consuls and consuls in Chinese treaty ports in the 1840s and 1850s. They ferociously fought to obstruct other businesses, monopolize the trade, and even compete with other consular employees to become the sole beneficiaries of contract legalizations, passports, and tax fees. Several consular employees were even at the centre of quarrels and international scandals related to the trafficking of emigrants.

Before the arrival of Cañete in Macao, the first vice-consul for Spain was James Tait, a British merchant with business interests in the coolie trade whose biography is of paramount relevance to the history of the South China trade. Tait's interest in occupying that post was clearly to profit from the shipping of Chinese emigrants, monopolize the trade, and charge ship duties.Footnote 37 He was named vice-consul in Xiamen in 1846 because the Governor General of the Philippines did not agree with the requests of Sinibald de Mas and the Board of Commerce of Manila for the proper establishment of a Xiamen consulate, which did not open until 1859. Mas had been suggesting for some years that there was a need for a consulate to protect Spanish interests in that port against the “irregular procedures of some Mandarins”.

James “Santiago” Tait lived for some years in Manila and could speak Spanish. When moving to Xiamen he sent a petition to occupy that position with no salary, just for “the honour of serving the Spanish Government”.Footnote 38 Tait enjoyed his position for nine years, between 1846 and 1855, but by the end became the centre of a quarrel with General Consul Cañete over the supervision of the embarkation of emigrants. In 1851 and 1852, he was also consular representative for the Dutch and the Portuguese in Xiamen, but after a revolt in 1852 against his office in Xiamen, Dutch authorities dismissed him. The British consul in Xiamen had warned of Tait's use of his Spanish consular status to coerce Chinese authorities and ship Chinese labourers.Footnote 39 When, in 1855, Cañete informed Tait he would be travelling to Xiamen to take over his consular responsibilities, Tait accused Cañete of going after the collection of ship duties. To Cañete's indignation, Tait disobeyed his orders and refused to cede him his responsibilities as vice-consul, alleging that Cañete had no authority over him and that he would only give up his post by royal order.Footnote 40 Cañete and Tait accused each other of acting according to their own interests.

Cañete was especially worried that the recent tragedy of the American ship Waverley, which Tait had sent to Peru, and on which 200 to 300 Chinese immigrants were discovered to have suffocated to death in Manila, could happen again. Cañete had travelled to Xiamen to promote Chinese emigration to Cuba, to protect commissioners of Cuban companies established in China by avoiding the development of monopolies, and to ensure that current regulations were being applied in the shipping of Chinese emigrants to Havana.Footnote 41 In particular, there were suspicions that Tait was using his double role as vice-consul and as partner and agent of a company dedicated to the shipping of Chinese emigrants to monopolize this trade by impeding other companies from doing business. Moreover, some commissioners for Cuban landowners established in China had complained that Tait was an obstruction to their businesses.Footnote 42

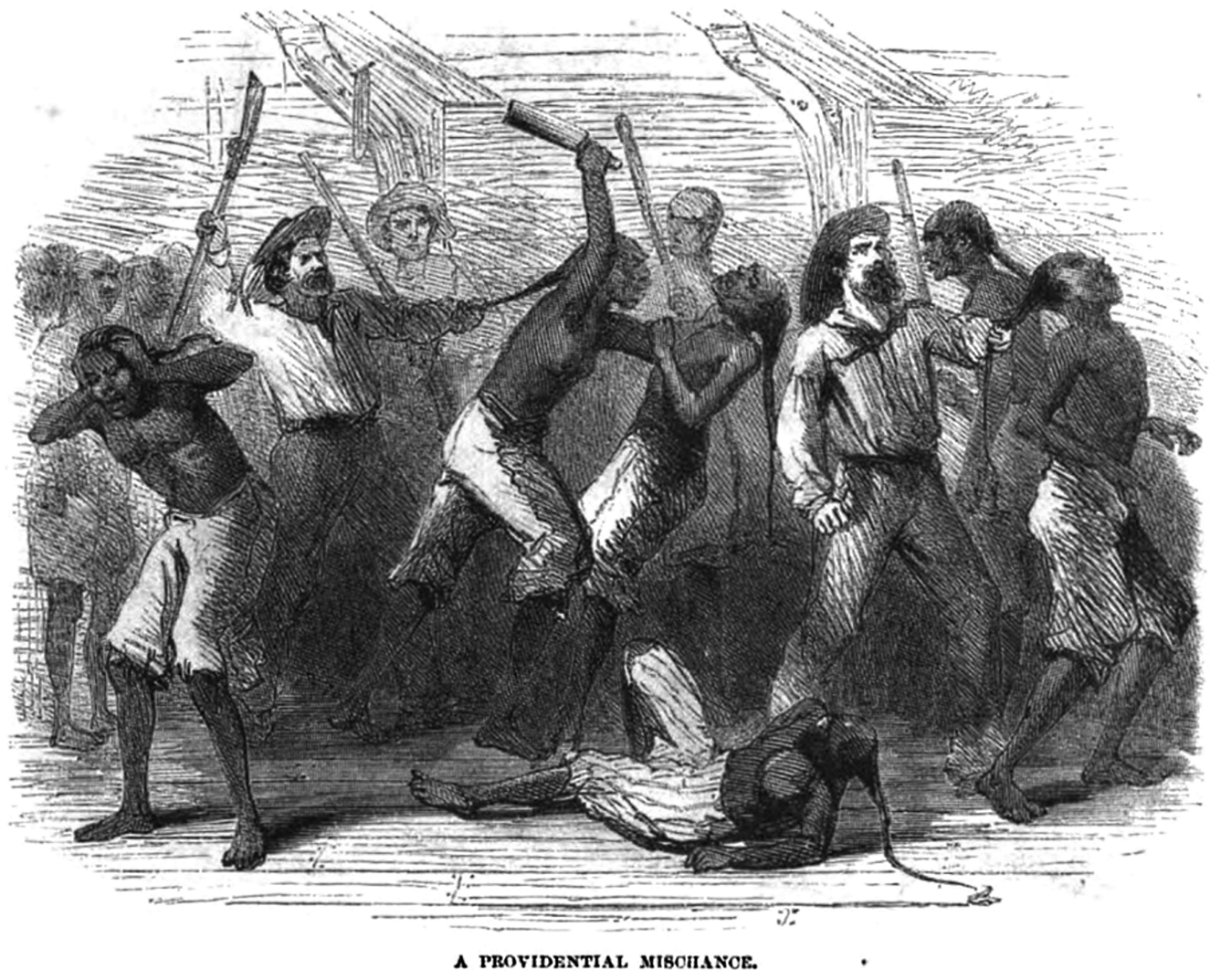

In turn, Tait accused Cañete of imposing extra ton rights on Spanish vessels for the Consulate's benefit, on top of what they already paid to Chinese customs: one third would go to the Xiamen Consulate and the other two thirds to Cañete.Footnote 43 Additionally, Tait alleged that while in Xiamen the consul had been involved in the violent embarkation of 580 unwilling Chinese emigrants on the Sea Witch (Figure 3). According to Tait, when Cañete entered the ship to check contracts, the emigrants declared they were unwilling to depart, and when not allowed to disembark, they broke into an uproar, quieted “with the tip of swords”. The day before sailing, the emigrants revolted and kidnapped the captain, obliging Cañete and others to flee, although a group of sailors later rescued the captain.Footnote 44 Whether Tait was telling the truth, or just getting back at Cañete, is difficult to assess.

Figure 3. Edgar Holden's depiction of a mutiny on board the Norway in 1859 is illustrative of the violence which often broke out in coolie ships.

“A Providential Mischance”, Edgar Holden, “A Chapter on the Coolie Trade”, Harper's New Monthly Magazine, vol. 29 (June 1864), p. 6.

Even though Tait had personal reasons to falsely accuse Cañete, the latter certainly obtained personal profit from certifying ships to Cuba and undertook irregular activities to benefit the trade. Pérez de la Riva explained how the Macao consul would commit fraud by allowing agents to embark more emigrants than registered and then cover it up, so as to balance possible losses – deaths – during the journey. Tait also makes reference to how Cañete declared that “the Xiamen vice-consulate must yield good earnings”, that “not charging ton taxes to Spanish vessels was good to shipowners but not to him”, and that “he had not come to China to enjoy the fresh air”, suggesting that Cañete's interest in China was mainly obtaining the extra income attached to the export of Chinese emigrants.Footnote 45 Indeed, Cañete always defended Chinese immigration to Cuba, opposed its detractors, and continuously looked to create more profit from this business.Footnote 46 For instance, he often reported to Spanish authorities in Madrid how “happy and satisfied” he found emigrants to be in ships before leaving Macao, even those ships where they later revolted.Footnote 47 He even asserted that several Cuban sources informed of “the humanity and sweetness” of their treatment there, and worked to disseminate news of this sort in China. He was also often in conflict with the international press and reported to Madrid's administration that the accusations published in British and US newspapers regarding deceit in the recruitment of emigrants were not true. For example, he suggested taking the newspaper Hongkong Register to court for defamation, for an article regarding the mistreatment of Chinese immigrants in Cuba, but he finally desisted for fear of possibly losing the case, as the damage to the trade would have even been greater.Footnote 48

The harbour of Shantou stands out as a source of rising consular competition. Tait had established a barracoon there and succeeded in allowing local authorities to collect Chinese emigrants for $1.5 per worker.Footnote 49 According to Tait, while in Xiamen, he obtained $1 for every legalization of Chinese emigrant contracts to Cuba, but he did not receive anything for contract legalizations in Shantou. Since Tait had the only foreign company and travelled to Shantou from time to time, he asked Cañete for permission to establish a section of the vice-consulate instead of sending in a new consular agent to address consular issues. Cañete, Tait declared, had asked him to charge $1.20 instead of $1 in Shantou, and to divide this tax with him. Tait named Charles William Bradley, the American acting consul, agent in Shantou.Footnote 50 A few days later, Cañete replaced Bradley with a Spanish agent to “protect Spanish interests”, and, according to Tait, to profit from the Shantou taxes.Footnote 51 The China Mail reported the news on Shantou's agent, and expressed disagreement with the naming of a Spanish consular agent in a harbour outside of the five open ports by a country with no treaty, that is, Spain. The paper's account even considered actions like this, in which countries with no treaty rights carried out trade with China, to be at the root of many “evils” sprung from Sino-foreign relations.Footnote 52

The person in charge of certifying ships leaving from Shantou in the 1850s was José de Aguilar. Given that he often issued positive reports on the embarkation of Chinese emigrants in that port hired by the infamous coolie agent Nicolás Tanco Armero, he probably overlooked the conditions of ships embarking from that harbour. In 1859, Hong Kong Governor John Bowring regretted how “A gentleman who has been living at Swatow […] informed me […] that the enormities committed in that neighbourhood in the collection and shipment of coolies exceeded all belief”.Footnote 53

Cañete stayed in Xiamen until March 1856 waiting for a resolution from the Spanish central government on Tait and taking care of “other service businesses” and “necessary negotiations to remove certain obstacles for the Island of Cuba”.Footnote 54 While Cañete was in Xiamen, Tait travelled to Europe and returned to Xiamen to continue dispatching vessels and collecting some of their licences.Footnote 55 Finally, Tait was officially dismissed, and the Spanish merchant and vessel captain established in Macao, Francisco Díaz de Sobrecasas, took over his position as vice-consul.Footnote 56

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST IN THE DOUBLE ROLE OF CONSULS

The unprofessionalism and hybrid commercial and official role of these consuls is especially clear in the further disputes which took place between Cañete and Miguel Jorro, Xiamen's first official consul (Figure 4). While occupying his post in Xiamen between 1857 and 1861, Jorro was at the centre of various scandals related to the coolie trade and turned out to be a recidivist criminal in later years. His presence in Xiamen coincides with the years of stagnation of the trade in indentured labourers in that port. His file in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is filled with cases of fraud and debt both in China and in Spain. In fact, in 1854, before obtaining his position in Xiamen, he already had an important debt with the tax return office of almost 16,000 reales.Footnote 57 As soon as he embarked to Xiamen in 1857, Cañete wrote to the First Secretary of State in Madrid to warn that Jorro had been claiming that he occupied Cañete's position on his trip to China. That same year, Cañete demanded Jorro's replacement by somebody more acceptable, as he had not only left his post to go to Europe without informing him, but had also shown an “aggressive and turbulent character” in the few months he had been in China.Footnote 58

Figure 4. Portrait of Miguel Jorro y Such.

Arxiu Municipal d'Altea (AMA), Fons Ramon Llorens Barber.

As soon as Jorro took on his post in Xiamen, he was again at the hub of a dispute with other Spanish consulates, as he also illegally named an agent in the port of Shantou, given that Cañete had not sent an agent there since the last monsoon. The agent named by Jorro told immigration agents that he could stamp Chinese emigrants’ contracts so that he could collect tax rights. It was that particular harbour's labour agent and partner in the Cuban recruiting company Rafael Torices, Agustin R. Ferran, who alerted Cañete to the presence of this new individual, although the man was able to dispatch at least two ships, the French frigate Anais and the British ship Robert Small, before Cañete could intervene.Footnote 59

One of Jorro's most notorious scandals has to do with his direct involvement in the coolie trade, as he tried to become an immigration agent while still occupying his post as consul in Xiamen and work for Rafael Torices. Jorro's plan was to facilitate the shipment of Chinese emigrants through a series of actions. According to his project, the company needing immigrants would contact him directly once a ship headed for China had departed. He would then prepare “the cargo” either in Xiamen, Shantou, Guangzhou, or Fuzhou, making sure that the emigrants were healthy and had signed up voluntarily. He would be in charge of all the recruitment costs, and the company would pay the deposit, food, and equipment until embarkation. The company would pay ten pesos to Jorro for every worker. Jorro, in turn, would be in charge of any costs derived from personal relations “which he had in China, […] where he had authorization from Her Majesty to promote by these means the agriculture of Antilles and the Philippines”.Footnote 60

The Spanish authorities in Madrid, shocked, immediately asked for a report from Jorro, who denied the accusation and in turn accused foreign immigration agents of taking revenge for his work on, precisely, trying to stop abuses against emigrants.Footnote 61 However, Jorro finally gave up on this plan and went on to commit other financial scams. For instance, in September 1860, there was a claim of fraud by an immigration agent, Pío Fernández de Castro, head of the company Don Ignacio Fernandez de Castro y Cª. He accused Jorro of owing him 5,000 pesos fuertes from a loan of 8,000. Tait & Company had given him the money to act as intermediary and pay for the advances of Chinese emigrants embarking on the ships Santa Lucia and Guadalupe in Xiamen. Jorro just paid 3,000 pesos for ninety-nine emigrants and kept the rest of the money. In retaliation, Fernández asked the Spanish government to retain Jorro's salary in Xiamen until the full amount had been satisfied.Footnote 62

Astonishingly, Jorro's dismissal by Madrid authorities did not have to do with his attempt to work simultaneously as an immigration agent and as consul in charge of upholding migratory regulations. Neither was he dismissed because of Pío Fernández's claims against him. He was finally discharged for having fled Xiamen in 1860 charged with committing fraud against a renowned Chinese family, the heirs of Chuidian, leaving for Europe with more than 20,000 pesos. European public opinion acknowledged Jorro's culpability.Footnote 63

IRREGULARITIES IN THE CERTIFICATION OF COOLIE SHIPS

From 1855, Spanish consuls were directly responsible for certifying ship conditions before departing to Cuba. These consuls’ role in the shipment of emigrants throws new light on the complex issue of why unwilling emigrant workers did not speak out when asked if they really wanted to emigrate during the embarkation. Together with Portuguese authorities in Macao, the Spanish consul and vice-consul were the last filter which emigrants would go through before the journey.Footnote 64 And this embarkation site in Macao was one of the points where the abuse was being overlooked. While brokers and crimps were key figures in the abuse, Spanish consular personnel and Portuguese authorities surely disregarded, as much as possible, whether or not these men left of their own will.

The role of brokers and crimps was paramount, since they often tortured prospective emigrants until they agreed to emigrate.Footnote 65 An anonymous letter to the editor of the Hongkong Register describes how brokers forced Chinese men to agree to embark:

I […] translated a Mandarins’ document setting forth the trickery of the Chinese pimps […]. When the foreign agent […] ask them if they were willing to go, if they said no – he would not take them. But they were still retained by the pimp, and tortured […] so as to say “hi lo” – yes! thereby jumping out of the frying pan into the fire!Footnote 66

Furthermore, Mandarins also pressured emigrants to emigrate by treating them as criminals if they decided to go back to their villages after being recruited in the barracoons.Footnote 67

These abuses often ended up with popular protests, which sometimes targeted Westerners in Xiamen, and which, at times, caused a temporary halt to the trade. This happened in 1852, 1857, and 1859.Footnote 68 In particular, the European community in Xiamen considered the barracoon system to be the main reason why these abuses could be committed, and on such a wide scale.Footnote 69

Cañete occasionally reported certifying ships’ conditions himself to avoid tragedies which would “give weapons to those interested in hindering this business”. This was the case with the Henriette Maria, where there had been a revolt. He would check the conditions of the ship, the amount and quality of food and water, whether workers had signed up voluntarily, and whether the latest dispositions published were being put into effect. However, Tait's accusations against Cañete and a mutiny on board the Fernandez, checked by Cañete himself in Macao, indicate that he certainly passed over the forced embarkation of workers who had not agreed on emigrating.Footnote 70 There were reports of relatives claiming that their family members had also been convinced to depart by force.

In February 1859, Jorro reported to Cañete that he had received claims from relatives of emigrants who had supposedly been forced to embark to Macao on Portuguese vessel Num. 45. They were to be later sent to Cuba but had no idea of where they were being taken to. Apparently, this lorcha and one or two other ships, either Chinese or Portuguese depending on the source, had left Camboe, a village near Xiamen, filled with unwilling emigrants. Jorro informed Cañete, as he was “the only one who could avoid this vile trafficking, since the victims are taken to Macao to later take them to Havana”.Footnote 71 Cañete replied, in a hostile tone, that all the formalities related to hiring, contracts, and embarkation were checked by him and Portuguese authorities in Macao, according to current regulations. Furthermore, no matter which tools brokers used to hire workers outside of Macao, once in the Portuguese enclave, emigrants had the protection of the law and no ship departed with them on it without their consent.

According to Cañete, workers on vessel Num. 45 were treated following standard procedure in Macao: they were first taken to the Senate before going to the receiving station, where the Royal Attorney read them the contract, explained the conditions, and asked them if they were emigrating voluntarily. They all answered affirmatively. However, Cañete asked Jorro to warn him of any emigrant engaged by “evil means”, specifying the names, details, and particularities of the Chinese who found themselves in this situation.

Just a few weeks before the lorcha Num. 45 case, Chinese local authorities had beheaded some of the most famous Chinese brokers. This had caused a temporary halt in traffic from Xiamen and Shantou, at least between the previous month of October and the following monsoon, with only one ship leaving Macao in that period.Footnote 72 However, the beheadings did not stop the kidnappings, quite the opposite. As a consequence of the interruption in trade, since inactive ships implied exorbitant costs for shipowners, they sent groups of lorchas to Xiamen in search of fishermen, who they kidnapped from their boats, leaving whole families bereft of their only means of economic support.Footnote 73

A few months later, in July 1859, the organization of another frigate, the Spanish Gravina, and other Portuguese ships, incited Chinese protests in Xiamen. As these were especially threatening to the foreign community there, a public meeting of Westerners was organized. Those who called the meeting affirmed that they had evidence of many cases of kidnappings in the last two or three weeks, the victims of which had been shipped on the Gravina and Portuguese lorchas. While British firms had already ceased to engage in such trade, these ships were at the port with the very purpose of renewing the coolie trade. The kidnappings took place in the streets of Xiamen and at Cheoh Bay, a trading site twenty miles inland from Xiamen. The organizers of this meeting of the foreign community issued a petition to Jorro to check the practices of coolie brokers with connections to Spanish vessels. However, although cases of kidnapping were allegedly taking place, Jorro was adamant that since his arrival in Xiamen, the abuses had stopped thanks to his own proceedings.Footnote 74

In fact, Jorro accused the meeting's committee of criticizing the coolie trade because it now benefitted a Spanish and a French agent instead of British business; the British had monopolized the trade for eight years without raising a voice against it. Moreover, he informed his superiors in Madrid that Chinese authorities had privately admitted to him that they believed emigration to be inevitable, and that they acted upon it only because the English were constantly censuring it. By 3 August 1859, the Gravina had left Xiamen for Cuba.Footnote 75

CONCLUSION

One of the main objectives of the Spanish consular organization in China was clearly enhancing Chinese contract labour emigration to Cuba. The involvement of Spanish representatives in the coolie trade shows how state-based imperial capitalist colonialism could often go hand in hand with private commercial business. This is true not only of this early Spanish consular establishment, but also of Spanish consuls from later decades and Spanish administrative authorities in the metropolitan government and in the colonies, as well as of representatives from other nations. They were all either involved in extracting private economic benefit from Chinese emigration or eager to do so. This highlights the role of middlemen in the trafficking of immigrants, especially those with administrative positions, a type of figure often overlooked by historians.

These consuls’ objective was to obtain pecuniary revenue by becoming middlemen in one step of the migratory structure. They benefitted from the accumulation and transit of labour by turning it into a commodity in itself. This opens up new ways of understanding the commodification of labour beyond service or in relation to slavery, since in this case, labour became a transnationally commercialized item within the industrialized plantation mechanism.

The crucial role of Spanish consuls, vice-consuls, consular agents, and other employees in sustaining the mistreatment of Chinese emigrants throughout the second half of the nineteenth century is irrefutable. These men were responsible for purposely overlooking abuses in the recruitment of emigrants, in the signing of contracts, and during embarkation. Historians of the coolie trade have traditionally pointed to brokers, crimps, emigration houses, and agents as the key figures in the development of an abusive migratory system. However, the financial ambitions of consular officers were also at the core of how Chinese emigration to Latin America became a dehumanized mass-migration trading business. They fiercely contended to obtain, unlawfully, the most profit from legalizations, the issuing of passports, tax fees, and ship duties, while disregarding exploitation and protecting this business from Western anti-trade condemnation.

The study of Spanish consular involvement in the coolie trade highlights various foci and questions which should be addressed in future research. To begin with, this study accentuates how little we know about the network operating the coolie trade business in Macao, Shantou, and Guangzhou. Consular personnel from other nations were also associated with the shipping of Chinese emigrants to various destinations, and the fees which they charged to emigrant ship masters were also important to their consulate's budgets. For instance, there is evidence which points towards the involvement of French consuls in the trade, and at least one author has mentioned that the Dutch reinitiated the trade to their colonies in the 1880s.Footnote 76 This study helps to underline how corruption in the Western consular structure was a widespread phenomenon that was limited not merely to Spanish nineteenth-century consulates. Further research on the various strategies played by different countries and their representatives in China in relation to the coolie trade to various destinations would deepen our understanding of the network behind the trafficking of Chinese workers to America. The association of other nations’ consular webs with the trade, such as those of the French or Dutch consulates, as well as the role of Chinese local authorities in all of it, is particularly enlightening, as it shows the extensive and multinational nature of the network operating behind colonial capitalistic exploitation of forced labour.