Introduction

In 2018, I spoke with Safia, the treasurer of a Ugandan grass-roots organization of women with disabilities called Tusobora,Footnote 1 about another of my research participants, Atugonza. Atugonza was a man who lived with epilepsy and worked carrying water and rubbish for stallholders in Kicweka market, where Tusobora was based. Atugonza’s epilepsy had remained untreated over many years, and those close to him described a gradual decline in his social and intellectual engagement. Atugonza himself talked of fits ‘gripping’ him and making him omuceke (a weak person). During fieldwork over the past year, I had paid close attention to how my interlocutors conceptualized marked bodilymentalFootnote 2 differences – forms of non-normative embodiment that are culturally elaborated as meaningfully different – and had identified several distinct discourses. Using a word that I had observed frequently, I asked Safia, who herself used a wheelchair, what she thought Atugonza’s ekizibu (problem) was. She responded with a long list of issues: he had to walk into Kicweka every day from his village, he did not get enough food, his family did not have land. After a pause, she added, unprompted, that he also had a problem with his head, calling this ‘oburwaire’ (sickness). I asked her whether, because of this ‘sickness’ or ‘problem’, he was ‘omuntu owain’obulema’, a person with disability. She replied ‘kwaha, baitu ain’ekizibu’ (no, but he has a problem).

In Ugandan legislation, by contrast, Atugonza would count as a ‘person with disability’, being included under the subcategory ‘Mental disability including psychiatric disability and learning disability’ in the medicalized list of conditions in Schedule 3 (Persons with Disabilities Act 2019). However, most of my interlocutors agreed with Safia, and he had never joined one of the organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) that have proliferated in Uganda since the 1990s. As Safia’s words show, however, ‘disability’ is not the only way people in Kicweka thought about bodilymental differences, nor the only way an argument for special treatment based on them could be phrased.

The term ‘disability’ emerged in Industrial Revolution-era Euro-America as a way of grouping radically different bodilymental experiences through (perceived) incapacity for standardized forms of work, in the context of the profit maximization imperatives of capitalism (Friedner and Weingarten Reference Friedner and Weingarten2019: 486; McRuer Reference McRuer2006: 92–3; Russell and Malhotra Reference Russell and Malhotra2002: 212–13). It was introduced to African countries (including Uganda) through colonial and postcolonial infrastructures including the state and international organizations (Whyte and Muyinda Reference Whyte and Muyinda2022: 423; Zoanni Reference Zoanni2021: 174–5). As a relatively recently introduced concept in the region, it necessarily coexists with other ways of understanding bodilymental difference, leading researchers to grapple with multiple epistemologies and ‘awkward translations’ between divergent terminologies (Livingston Reference Livingston2006: 113).Footnote 3 Nevertheless, the relationships between ‘disability’ and alternative concepts of bodymind variation have received little attention – perhaps, as Lavern argues, because of the complexity of studying such overlaps (Lavern Reference Lavern2021), especially in the context of epistemic inequalities.

This article, based on eighteen months of fieldwork with Tusobora, considers the discourses about bodilymental variation that circulated among members and non-members of the organization in and around the market, focusing particularly on the practical politics of making claims to resources and social belonging. The word obulema (disability) was commonly used by the core members of Tusobora and others who were familiar with them, including people working within Uganda’s system of political representation for people with disabilities, and in NGOs. However, it was rare outside these groups. Omuceke (a weak person) and the related term ekizibu (a problem) formed a more common and widely known discourse used to refer to people living with the types of marked bodymind differences that obulema also referred to. However, the two terms are linguistically and conceptually divergent. Obulema (disability) is an individual condition, referencing a non-normative embodied state that conveys disadvantage. To recognize someone as an omuceke (a weak person), by contrast, requires attending to a person’s bodymind and their socio-economic circumstances and relationships. While obulema is primarily an objectified individual category connected to citizenship and defined in relation to the legal-political realm, whether someone is an omuceke is determined interpersonally, in a relational setting.

Despite recurrent calls to ‘centre epistemologies of the south’ (Afeworki Abay and Wechuli Reference Afeworki Abay and Wechuli2022: 31; Erevelles Reference Erevelles2011; Meekosha Reference Meekosha2011), most research into how disability is conceptualized still focuses overwhelmingly on models developed in the global North, such as medical, social and human rights models (see, for example, Meyers Reference Meyers2019; Lawson and Beckett Reference Lawson and Beckett2021; Brocco Reference Brocco2024: 10). These models also have practical effects. The Ugandan government, like many in the global South, is highly influenced by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). ‘Omuntu owain’obulema’ (a person with disability), the phrase commonly used within Ugandan OPDs, is a direct translation of the English phrase used in the CRPD, which was adopted without change into Ugandan legislation (which is also in English). As an international human rights instrument, the CRPD conceptualizes disability rights as rights provided by the state, entailing an individualist citizenship-based approach to what ‘disability’ and ‘people with disabilities’ are (Meyers Reference Meyers2020). In this article, I describe this (and other conceptually similar approaches) as ‘legal-political’ concepts of disability.

Some recent works critique the individualist basis of legal-political approaches, pointing out evident misfits between the liberal-individual tradition of citizenship as equal status in rights and interdependence-based forms of social belonging, which exist in many places, including Uganda and the USA (Meyers Reference Meyers2020; Schalk Reference Schalk2022: 7). Schalk and other theorists propose conceptualizing disability justice in another way, through interdependence and collective access (Berne Reference Berne2015; Onazi Reference Onazi2019; Schalk Reference Schalk2022: 92–5). I classify this group of approaches as ‘relational’ concepts of disability. Onazi, developing Gyekye’s African communitarian philosophy into a proposal for disability justice based on relational obligations, argues that in Gyekye’s relational community ‘[t]he relational character of the individual, which is grounded upon his or her natural sociality, not only provides justifications for obligations, but also the orientation of individuals to those they share a community with’ (Onazi Reference Onazi2019: 143). This approach resonates with the omuceke discourse I describe. My research clarifies that, in the setting I worked in, the ‘orientation of individuals to those they share a community with’ and the obligations entailed attach not to categories of people, but to specific others with whom the self emerges through an ongoing history of interaction. This is in stark contrast to legal obligations, which apply based on ‘category work’ performed to fit into fixed abstract definitions (Friedner et al. Reference Friedner, Ghosh and Palaniappan2018: 5).

Importantly, Onazi suggests that relational and individualist rights-based approaches to disability justice, while fundamentally different, might not be incompatible (Onazi Reference Onazi2019: 130). Following his insight, this article gives a practical account of how two radically different ways of understanding bodymind-related disadvantage intersect, focusing on how models of disability and/or non-normative embodiment operate in people’s lives and the effects they create (as advocated by Businge Reference Businge2016: 817).Footnote 4 The concepts of ‘disability’ and omuceke (a weak person) both played vital roles in my interlocutors’ lives, but they were used in different situations, with different roles and effects. My contributions lie in analysing the discourses’ different accounts of obligation and rights, and tracing how they invoke diverging types of relationships. This allows me to show why people with disabilities might use both discourses, despite their sometimes contradictory implications. It also enables me to differentiate within the category ‘people with disabilities’, showing the differences (and inequalities) that ideas about embodiment can generate, especially when materialized through powerful postcolonial and neocolonial infrastructures.

Disability in Uganda: methodological and contextual notes

Uganda has a unique system of political representation for people with disabilities, established by President Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) government through a constitution in 1995 and subsequent legislation in 1997. This mandates reserved places in parliament and local councils for people with disabilities, who are elected through a complex system of OPDs (Ndeezi Reference Ndeezi2004; Modern Reference Modern2021: 26–8). As the only country in the world with such institutionalized involvement of people with disabilities in local government, Uganda offers an important setting for investigating legal-political approaches to disability. Historians of the Ugandan ‘disability movement’ attribute the inclusion of its concerns in the constitution to national and international factors: the activities of local OPDs, with support from a ‘women’s caucus’ funded by foreign donors (Katsui Reference Katsui, Katsui and Chalklen2020),Footnote 5 and political influence from the army and injured veterans in the (post-)conflict setting (Muriaas and Wang Reference Muriaas and Wang2012: 320). Influences from international discourses are evident in Ugandan legislation. The Persons with Disabilities Act 2006 (updated in 2019) contains a CRPD-inspired ‘hybrid’ approach to disability, which welds a ‘social model’-influenced overall definition, recognizing the role of environmental factors in disabling people, to a list of qualifying ‘categories of disabilities’ expressed as medical conditions (Kett and Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development Reference Kett2020: 10).

In its early days, the NRM government included ‘formerly marginalized groups’, especially women, in its governance structures, aiming to appear to be a more inclusive ‘state power with a difference’ and win over a divided population, as well as international donors (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996: 200, 209). As the culmination of this policy, people with disabilities were one of three ‘special interest groups’ that were allocated reserved places in local councils in 1997 (along with women and youth). Consequently, these groups are conceptually associated with the NRM and Museveni (Ahikire Reference Ahikire2017). This context encourages ‘civil’ or ‘quiet’ politics among people with disabilities involved with the government system, which diverges from the liberal model of individuals making claims on the state, at times causing conflict with international NGO-promoted disability advocacy strategies (Modern Reference Modern2021: 39–43, 234; see also Whyte and Siu Reference Whyte and Siu2015 on ‘civil’ politics in Ugandan healthcare).

Data used in this article were collected during eighteen months of participant observation with a small grass-roots OPD called Tusobora between 2017 and 2019, which I undertook following a six-month period spent intensively studying the languages Runyoro and Ugandan Sign Language. During the fieldwork period, I spent most days in the market where Tusobora was based, conducting participant observation or interviews. I also followed members of Tusobora as they moved to other settings, including home villages, local council offices, meetings of NGOs and OPDs, and commercial hubs. Tusobora members interacted most with two elements of disability-related infrastructure. One was the councillors for people with disabilities. Tusobora’s secretary was a councillor for women with disabilities at the municipal level. She worked closely with the other councillors and a civil servant, the community development officer (CDO), who also frequently visited the market to discuss policy and activities with Tusobora members. I consequently attended council meetings, council away days, and constituent advice and advocacy sessions with two councillors for people with disabilities.

The second was a government programme called the ‘Special Grant’ (administered by the CDO), which funded people with disabilities to set up or expand small businesses. This was the only government initiative specifically targeting people with disabilities, although they could also access other projects such as the Uganda Women Entrepreneurship Programme. Few of the government’s legislative commitments on disability were realized: for example, there was no evident attempt to make medical or education services accessible or to tackle discrimination by employers (see also Nett Reference Nett2023: 181). Special Grant payments were small (around 200,000 UGX (£40) for each individual), so only a limited set of micro-businesses could be established using this route. People with disabilities in the town therefore predominantly ran small market stalls (the occupation of all Tusobora’s core members) or worked as self- or casually employed tailors, knitters, hairdressers or carpenters. Many had been trained in these skills through a livelihoods project targeting people with disabilities, run by an international NGO (similar programmes are common across Uganda: see Schuler Reference Schuler2020).

I also interviewed and carried out participant observation with people with disabilities who spent time in the market but were not members of an OPD, many of whom lived with impairments affecting cognition and communication, like Atugonza. Although the Persons with Disabilities Act’s list of ‘categories of disabilities’ includes ‘Mental disability including psychiatric disability and learning disability’, in practice people living with impairments considered to affect cognition rarely accessed the representative system of councillors or the Special Grant and NGO training programmes. Earlier research also noted low engagement in Ugandan disability infrastructure among people living with ‘mental’ impairments (Ndeezi Reference Ndeezi2004; Yeo Reference Yeo2001: 23). While investigating the differential engagement of subgroups of people with disabilities, I paid attention to interactional patterns and linguistic tropes, allowing me to map different uses of discourses about embodiment between core, peripheral and non-members of Tusobora, using continuous case comparison.

The main ethnographic section of this article presents a legal case, during which a councillor for people with disabilities represented a rural constituent accused of encroaching on her neighbours’ land. I attended the hearing with the councillor and recorded it (with permission from all participants). I also interviewed some participants in Runyoro and English before and after the hearing. Although I was not fully fluent in Runyoro, I was able to follow proceedings with ease. Data presented are based on my contemporaneous notes, as well as a close study of the audio recording of the hearing, which included checking my interpretations of complex or technical utterances with bilingual native speakers. Neither the councillor nor his constituent belonged to Tusobora, although both were well known to Tusobora members due to their involvement in the wider network of OPDs and political representation in the town. The case study is presented here, alongside discussion of more everyday experiences of discourses about bodilymental variation, because participants in the case explicitly presented a range of claim-making narratives based on having obulema (disability) and being omuceke (a weak person), allowing me to illustrate how they differ, diverge and come together. In addition, it allows me to explore a core element of the Ugandan representational system for people with disabilities that has so far remained understudied: how councillors represent their constituents.

The next two sections look at the discourses about bodilymental difference my interlocutors used. I demonstrate how the specifics of the government and NGO infrastructure affected these concepts and the consequences of their use, including how they are implicated in the relative exclusion of people living with cognitive or communicative differences.

Obulema (disability)

Ugandan legislation is in English, using the terms ‘disability’ and ‘people with disabilities’. In Runyoro, the predominant spoken language in Bunyoro, the term used to translate ‘disability’ is obulema. This is likely a recent introduction to the language and is not widely used (see Zoanni Reference Zoanni2021: 174 on cognate Luganda terms). It is part of a longer phrase, ‘abantu abaina kwina obulema’ (people who have disability), used almost exclusively by disability rights advocates. However, obulema is formed from the more common word omulema, which means ‘a lame person’.Footnote 6 The linguistic difference is the noun class. Omulema, which contains the particle -mu-, is a personal noun, while obulema has the particle -bu-, which in this case makes it an abstract stative noun. The -mu- category indicates a person; -bu- indicates a state. Where omulema makes ‘lameness’ a characteristic of the person, with the term obulema one can refer to disability without talking about a specific person – ‘disability’, not ‘a disabled person’. Consequently, it is possible to consider a person’s status as ‘disabled’ separately to the contextual, personal and relational details of their life. This makes the term particularly suitable for abstract categorization, including the biopolitical governance involved in contemporary Ugandan statecraft. Despite deriving from a word for a specific impairment, obulema has now been generalized among disability advocates and can be used for all types of physical and sensory impairments. This change is associated with the growing importance of disability as a social category in Uganda between 1981 and 2008, the main period of the NRM government’s infrastructure development (Zoanni Reference Zoanni2021: 174–5).Footnote 7 Obulema is also, however, associated with people who are directly engaged with government representation or programmes for people with disabilities, and is primarily a legal or bureaucratic category.

This usage is encouraged by technical processes involved in accessing government grants. To qualify for the Special Grant, people with disabilities must form a group and register with the government. They then submit an application, the core of which is a list of the members with accompanying photographs and descriptions of their individual projects, each with a budget. The list of members specifies their position in the organization (for example, chairperson, secretary, member, etc.) and impairment type.Footnote 8 Members of OPDs were so accustomed to writing their impairment group on documentation, I sometimes witnessed them mistakenly enter it on forms that in fact asked for other information. Members were taking part in a bureaucratic exercise of categorization demanded by organizations that were themselves subject to audit and had to provide evidence that they had reached appropriate ‘beneficiaries’. For the local government, audit was by central government; for NGOs, their funders. The appropriateness of beneficiaries was determined on a purely individual basis, through a depersonalized bodilymental assessment. Anyone who qualified within the government’s definition of ‘person with disabilities’ was a possible recipient, but there was no specific obligation to a particular disabled person, so anyone could also be turned away, for example if the annual budget had been exhausted.

Processes for accessing funding located ‘disability’ firmly in the bodyminds of individuals affected. However, aspects of a more social understanding of disability also featured within the bureaucratic complex. During a training session, the CDO argued that the Special Grant had been established because people with disabilities were discriminated against in employment, so they should be enabled to become self-employed (see Nalule Reference Nalule2012: 43–4 for a similar argument). Clearly, he thought social arrangements caused at least some of the problems associated with disability. Like the Persons with Disabilities Act, local government operated with a hybrid social and medical concept of disability. However, the more important aspect of how obulema/disability was conceived was its association with a certain type of relationship and form of obligation: that between an individual person with disabilities and the state. For the state, the key characteristic was its abstract biopolitical form of qualification, which engaged the state’s duty towards a citizen living with disability.Footnote 9 For people with disabilities, the relational context of obulema produced a reciprocal obligation to support the state, including politically,Footnote 10 and by using the business inputs provided responsibly. Consequently, economic behaviour was highly regulated in the group, with the core members presenting themselves as diligent and parsimonious managers of the resources they had been given (see chapters 1 and 2 in Modern Reference Modern2021; see also Schuler Reference Schuler2020: 125–6). The leadership judged members, and each other, against a strict standard encapsulated by the term ‘active’, widely used in Uganda to mean being clever, enterprising, hardworking and persistent.

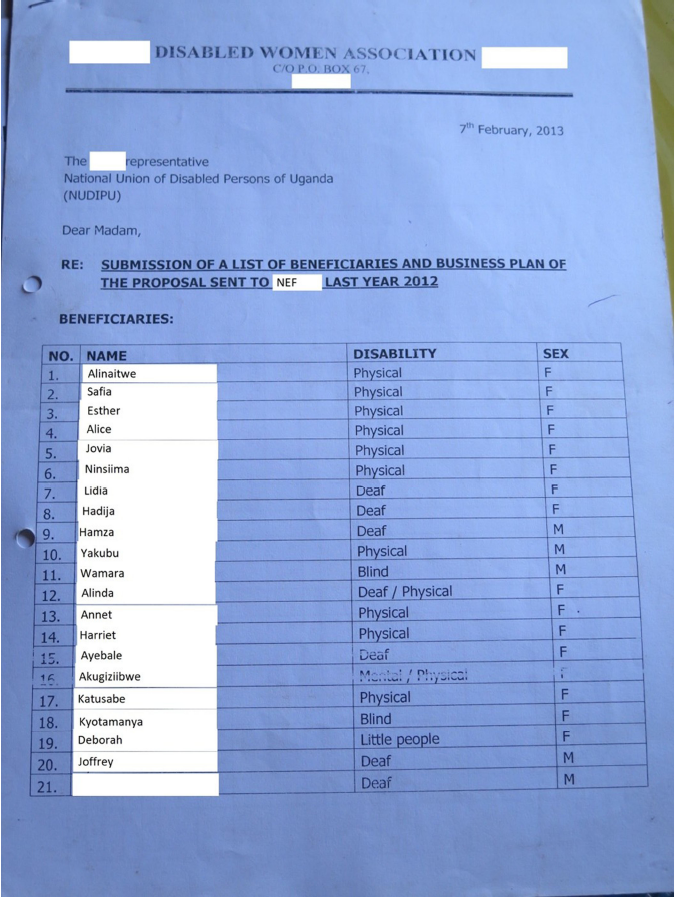

The disciplinary aspect of the concept profoundly affected the make-up of group membership. Figure 1 shows the beneficiary list from an application Tusobora submitted to an NGO, specifying each member’s impairment type. Most listed members are categorized as ‘physical’ or ‘deaf’, a few ‘blind’. The ‘qualifying impairments’ listed in the Persons with Disabilities Act include ‘Mental disability including psychiatric disability and learning disability’. However, only one member, Akugiziibwe, is listed as having a ‘mental’ impairment, and her entry reads ‘mental/physical’. Akugiziibwe lived with partial paralysis, was described as a ‘slow learner’, and periodically experienced intense mental distress. She was a member of Tusobora because of her physical impairment, and most members considered her ‘slow learning’ and intermittent distress irrelevant to her membership.Footnote 11 Although she was formally a member of the group, she was marginalized within it and often excluded from its funding and projects because she was not thought to be able to manage a business, the core activity of the group and of much of the wider disability-related infrastructure. No members of Tusobora were included because of experiences that could be considered ‘mental’ or ‘cognitive’; nor did I find any such members in other OPDs in the town.

Figure 1. Tusobora beneficiary list from an application to an NGO.

Abaceke (weak people)

People thought to be ‘mad’ or ‘slow’, like Akugiziibwe and Atugonza (the man with epilepsy discussed in the introduction), were more often referred to using the alternative abaceke Footnote 12 (weak people) discourse. This discourse, which could refer to all types of impairment referenced in the Persons with Disabilities Act, also incorporated the terms ebizibu (problems) and oburwaire (illness). For example, the effects epilepsy had on Atugonza were variously described as ‘ekizibu Footnote 13 ky’obwongo’ (a problem of the head) and ‘oburwaire’ (sickness), and both he and others told me he was ‘omuceke’ (a weak person), in part because of his illness (see also Whyte Reference Whyte and Jenkins1998: 171). However, the main difference is not semantic range, but how the discourses are applied to people. Somebody who is ‘omuntu owaina obulema’ (a person with disabilities) will be so even if their social and economic situation changes dramatically, because the category refers only to their bodilymental state. By contrast, someone is assessed to be ‘omuceke’ (a weak person) in social context. Bodilymental impairment alone is insufficient; other factors, such as poverty, landlessness or orphanhood (all suggesting social isolation), must be involved, and the discourse can also apply to people who do not live with bodilymental impairment but have a combination of other types of problem. The core members of Tusobora were not normally considered abaceke, even though many did experience bodily ‘weakness’, because they had businesses and families: they were not isolated or extremely poor. Older people were often abaceke (weak people), especially if they experienced economic injustice and physical infirmity together; I heard the term used frequently about older people dispossessed of land in intra-family land disputes. Using a walking stick (omwigo) was an important symbol in this context, used to justify the claim to be an omuceke and therefore deserving of special consideration.

Talk about someone being omuceke (a weak person) or having many ebizibu (problems) often formed part of an argument that they were entitled to assistance. The discourse draws on a complex system for understanding and dealing with misfortune, which stresses social factors because an individual’s personhood is not separate from that of others but emerges in social interaction (Whyte Reference Whyte1997: 60; see also philosophical accounts in Gyekye Reference Gyekye1997; Onazi Reference Onazi2019). It is based on the idea, common in Bunyoro, that sharing history with someone creates obligation towards them, and breaching that obligation is dangerous. In the 1950s, Beattie glossed this idea as ‘neighbourliness’, writing that, in this mode of sociality:

People should live near to and help one another, even though they are not related as kin, and a man who lives apart from his fellows lays himself open to suspicion of sorcery. Eating and, especially, drinking beer together express the friendly relations which should subsist between neighbours. (Beattie Reference Beattie1959: 83)

This system creates a constant flow of small goods, especially foodstuffs, between households, at least in rural areas where food is grown rather than purchased.

Expectations of neighbourliness included providing support for one’s ‘weak’ neighbours. For some abaceke (weak people), like Akugiziibwe, these everyday contributions provided a substantial proportion of household subsistence. Akugiziibwe undertook a deliberate strategy of creating relationships that could carry this obligation, placing herself in others’ social space through repeated acts of asking, giving, receiving and service (similar strategies are described in Monteith Reference Monteith2018: S19–S20; Scherz Reference Scherz2014: 88; further detail is given in Modern Reference Modern2021: 179–92). This system is not analogous to ‘charity’, which in this area is understood to be a disposition to help people in need outside of specific obligations to that person and therefore applies most appropriately to strangers (Scherz Reference Scherz2014: 25). Rather, helping abaceke was obligatory, and the experiential force of the obligation was explained through the effects of long-term co-residence and familiarity. Akugiziibwe’s neighbours explicitly disavowed having a generalized disposition to help; instead, one told me that seeing Akugiziibwe hungry ‘caused her pain’, while others felt obliged because, as they put it, ‘we have ever been together’. In saying this, they demonstrated that their intersubjective history had linked their affective states in a very concrete way.

The obligation to help an omuceke is fundamentally different to the abstract legal obligation of the state to assist ‘abantu abaina obulema’ (people with disabilities). It attaches not to a category of people, but to a particular person with whom the self is socially related, and it is invoked by a specific historical-relational context. Again, the linguistic details are illuminating. In Runyoro and similar Bantu languages, virtually any descriptive personal noun can be made into a stative noun by replacing the ‘mu’ prefix with ‘bu’, as omulema (a lame person) is turned into obulema (disability). But I almost never heard people do this with the word omuceke. Even those who regularly used obulema rarely said obuceke, which would mean weakness. Instead, people talked about an individual omuceke or a specific, collective group of abaceke (for example, ‘Kicweka haroh’abaceke baingi [There are many weak people in Kicweka]’). They talked about an instance of being weak, not the concept of weakness, because being weak was socially meaningful specifically within relationships.

Claiming ‘disability’ and being ‘a weak person’ in a land dispute

The following case study, in which I describe a legal process involving Dorcas, a woman living with visual impairment in a village near the town in which Tusobora was based, illustrates the contrast between obulema/disability and abaceke/weak people. I focus on the language used about Dorcas’s embodiment, and the types of relationship and obligation different ways of talking about it invoked. Dorcas had been accused of encroaching on her neighbour and co-clansperson’s land. Her adult daughter had been briefly arrested for ‘malicious damage’ because she had cut down part of the neighbour’s maize crop and planted her own groundnuts instead. Dorcas and her daughter (who lived elsewhere but sometimes cultivated food at her mother’s home) claimed the land was theirs and their neighbours had moved the boundary stones. All the parties were summoned to a hearing at a local councilFootnote 14 to determine the facts of the case and correct the boundaries.

Dorcas was well networked with organizations of people with disabilities, especially the district union of blind people. When she received the summons, she telephoned one of the district councillors for people with disabilities, who also belonged to the union of blind people, and asked him to represent her at the hearing. This councillor was unavailable but passed the case on to the equivalent councillor at the level below,Footnote 15 Mugisa, who also lived with visual impairment and belonged to the union. I had been working closely with Mugisa, so I was able to join him to witness several stages of this legal case, including his initial conversation with Dorcas immediately before the hearing, the hearing itself, and the land-titling process in its aftermath. Dorcas’s and Mugisa’s language about her experience with visual impairment changed over the stages of the dispute. Paying close attention to these differences reveals the affordances of different ways of talking about bodymind variation, and the effects they have during land disputes in particular.

During the exploratory interview before the hearing, Dorcas explained that her maternal grandfather had held legal title to the land she lived on. She claimed that he had given a section of his land to her when she married because he was worried that, because of her visual impairment, she would be neglected by her husband and in-laws if she moved to their land, which is normal in this virilocal area. She therefore represented her unusual tenure arrangement as directly related to disability discrimination. Throughout this conversation, Dorcas and Mugisa used language associated with the legal category ‘disability’, including obulema (disability) and obugabe (rights).

During the hearing itself, Dorcas and Mugisa continued with obulema-based language. Mugisa introduced himself as ‘omu h’abantu barwanira obugabe … bw’abalema’ (one of those people who fights for the rights of disabled people). Dorcas repeatedly referenced the ‘ekitebe ky’abalema’ (OPD) she was a member of. She claimed that her neighbours had moved the boundary markers without her knowledge because she couldn’t see where they were. Dorcas’s accusers took a different approach, denying the case had anything to do with Dorcas’s visual impairment.Footnote 16 They claimed they did not discriminate against her. Rather, Dorcas was the aggressor. She repeatedly encroached others’ land, telling them they could not prevent it because she had the support of a powerful OPD.

While Mugisa consistently used the language of obulema/disability when he spoke about Dorcas’s visual impairment during the hearing, he did not, in fact, talk about it often. He accepted Dorcas’s accusers’ argument that this was not a case of disability discrimination, expressing outrage that she had threatened the other land users with action by the OPD and cautioning her against using disability to ‘kumigiriza’ (oppress) others. Dorcas’s reputation in disability circles played into this reaction: she was considered overly litigious and had a long history of disputes with the same neighbours. Instead of arguing her case based on disability rights and the specific position of women with disabilities in relation to land, as Dorcas had in the earlier interview, Mugisa put his rhetorical power into trying to achieve reconciliation between Dorcas and her grandfather’s heir, who was Dorcas’s maternal aunt. Mugisa likely considered this the most promising route to a resolution in Uganda’s consensus-based local council adjudication system,Footnote 17 but he also explicitly dismissed the argument that rights to land could pass through maternal families in this patrilineal area and told Dorcas she was allowed to stay only on the sufferance of her aunt and should therefore ‘humble’ herself before the heir (for more detail, see Modern Reference Modern2021: 217).

The case was ultimately decided against Dorcas, who was found to have encroached on her neighbour’s land. However, towards the end of the meeting, after Mugisa’s insistent entreaties, Dorcas did reconcile with her grandfather’s heir, begging her forgiveness for neglecting to visit her in the past (a serious breach of appropriate relationality). To do so, Dorcas switched languages towards the ‘omuceke’ discourse: she claimed she had not visited because ‘nkaceka’ (I was weak) and therefore she did not have anything to bring her aunt as a gift: ‘Ndi nka mulema, ninyowe nkusiima nka ki [I am like a lame person, how can I thank you]?’ After the reconciliation, the heir awarded her formal title to three acres of land to ensure security of her tenure in the future, drawing up a legal document on the spot with the help of the officials.

After the hearing, finalizing the land transfer took several weeks. The land had to be surveyed and new boundaries marked and recorded. Dorcas was asked to pay remarkably high fees for this, which Mugisa attributed to resentment from the village (LC1) council officials in charge of the process and the neighbours providing labour. Responding to this unfairness, Mugisa’s approach to arguing the case also changed: he appealed to the neighbours to have pity and recognize that, as an omuceke (a weak person), Dorcas could not raise so much money. However, they rejected his characterization of Dorcas, arguing that while she was visually impaired, her daughters were not. They would also benefit from the land and could contribute to paying for the survey. Dorcas was connected to their physical power and resources, so she was not truly ‘weak’. When Mugisa’s attempt to present Dorcas as an omuceke failed, he changed tactics again, alleging discrimination against a person with disabilities and calling a journalist from a local radio station to come and record what was happening. After this, the requested payment was quickly halved, and Dorcas was able to raise enough money from her daughters and her disability-related connections.

Strategic positioning through language: a discussion

Mugisa’s and Dorcas’s changing language demonstrates the care with which people chose discourses about bodymind difference when making claims about land. Obika et al. write that, in land disputes, ‘contestation is very often about placing oneself in a strategic position … People, as social beings, have options, possibilities for taking alternate identities’ (Obika et al. Reference Obika, Adol, Babiiha, Whyte, Bruun, Cockburn, Risager and Thorup2017: 217–18). Because the two discourses about bodilymental variation and disadvantage are connected to divergent forms of relationship and sociality, their use depends on interpersonal context, and they offer very different strategies for claim making. During the pre-meeting, Dorcas had established the basis of her land tenure to be rooted in attempts to combat disability discrimination. Her argument was based on an implicit understanding that in this area the normative way for women to access land is through their husbands, and therefore ‘their claims as wives are only as strong as their partnerships’ (Whyte and Acio Reference Whyte and Acio2017: 31). Women with disabilities are less likely to marry, and, when they do, more often abandoned by their husbands (Lwanga-Ntale Reference Lwanga-Ntale2003: 13–14; Whyte and Muyinda Reference Whyte, Muyinda, Ingstad and Whyte2007: 305; Barriga and Kwon Reference Barriga and Kwon2010: 24–5). Dorcas’s relationship with her husband was indeed never formalized, and it lasted only a short time. If women’s normative form of access to land is ‘only as strong’ as their relationships, women with disabilities are particularly disadvantaged. Discrimination against women and people with disabilities is outlawed by Article 27 of the Land Act 1998, so Dorcas’s approach offered a possible strategy for arguing the case, as well as making it clear to Mugisa why it was appropriate for him to advocate for Dorcas’s rights.

During the hearing, however, Dorcas did not mention this argument, and nor did Mugisa. While they continued with similar disability-related language, Dorcas’s focus was clearly on demonstrating her political power to be greater than that of her opponents, rather than on the nuanced argument about being given land by her grandfather on marriage. She employed an outrightly combative, even aggressive, tone. In Uganda, land disputes are often conceptualized explicitly as contests of strength. ‘Land grabbing’ is a common phrase in newspaper reports and villager accounts, which also discuss participants in terms of power versus vulnerability (Ahikire Reference Ahikire2010: 36). Mugisa and Dorcas both attributed the positive outcome of the case, which saw Dorcas’s security of tenure increase despite the finding that she was in the wrong, to the presence of Mugisa and me, arguing that we had demonstrated Dorcas to have ‘power from outside the local arena’ (Khadiagala Reference Khadiagala2001: 57), and therefore we had ‘scared’ the other participants.Footnote 18

In the context of the hearing, where Dorcas was so evidently connected to power, claiming to be an omuceke/weak person would likely have been counterproductive; the only time she did so, she used the past tense ‘nkaceka’ (I was weak), when she was explaining her previous neglect of her aunt, a crucial family member. Mugisa’s single use of the word omuceke (a weak person) occurred during the land-titling process following the hearing and was directed not at the higher-level council chairperson who ran the hearing, but at Dorcas’s village’s chairperson and her immediate neighbours. These are people with whom, due to the ‘neighbourliness’ norm, it would be assumed that Dorcas interacted on a very regular basis. As I argued in the earlier section on the abaceke (weak people) discourse, over time these neighbourly interactions often build an intersubjective history and affective bonds that can carry the weight of obligation towards an omuceke (weak person). Many of the disabled people I worked with who relied on this kind of neighbourly assistance were remarkably diligent in visiting their neighbours, deliberately putting themselves into shared everyday spaces to foster the relationship. Mugisa’s appeal sought to engage these affective processes.

His attempt did not work for two reasons. First, Dorcas had evident connections to power, including the physical power of her adult daughters and the political power of the disability infrastructure: the effects of her strategy during the hearing were still being felt. But just as importantly, due to the long-running disputes, the daily interactions expected between neighbours were absent in Dorcas’s local relationships. She did not visit her neighbours or treat them in the ways that they expected as neighbours and co-clanspeople; in turn, they did not feel reciprocal obligations to her. In these circumstances, what worked instead was another threat: calling a journalist and alleging disability discrimination. Conversely, Dorcas’s appeal to her aunt for special consideration as an omuceke did work, prompting the aunt to excuse her niece for not performing the visits due to her as a sign of respect for her senior position in the family. Unlike Mugisa’s appeal to the neighbours, which requested adjustments to the monetized bureaucratic process of land surveying, the exchange between Dorcas and her aunt was focused on re-establishing the relationship, a highly appropriate topic for the omuceke discourse.

Claims based on the two discourses were therefore appropriate to different settings. Before I summarize the details of this distribution, one final note on the logical form of the discourses is important here. Although obulema/disability and omuceke/weak person may appear to form a binary, the former emphasizing connection and the latter isolation, the discourses are not opposites because the forms of connection and isolation involved are different. As I have shown, the connection involved in obulema is based on relativelyFootnote 19 impersonal bodilymental categorization, while the isolation of omuceke represents an absence, or sometimes a betrayal, of specific personal connections. As the discourses do not engage the same kinds of settings or relationships, they are not always mutually exclusive. The relationship between them can be thought of, following Waters, as an example of ‘non-binary dualism’, a ‘syntax that puts together [dual] constructs without maintaining sharp and clear boundary distinctions … plac[ing] the two constructs together in such a way that one would remain itself, and be also a part of the other’ (Waters Reference Waters and Waters2004: 98–9).Footnote 20

The omuceke (weak person) concept itself, I argue, is also an example of non-binary dualism.Footnote 21 While having strength (amaani) and being an omuceke (a weak person) are paired concepts, they exist on a continuum with fuzzy boundaries, and any individual will have elements of their life and social situation that point to both. Judging if a person is strong or weak is an inexact contextual act, performed from an involved position within a particular social setting. This ambiguity made it possible for Dorcas’s aunt to accept her self-presentation as an omuceke during one section of the meeting, as having purchase specifically with regard to their relationship, even while her co-clanspeople neighbours rejected Mugisa’s argument that she was an omuceke within the same extended process of negotiation about land access. Having connections to the political power of obulema (disability) forms part of the complex that must be considered when making such a judgement, rather than being a direct negation of being an omuceke (weak person). Although the implications of claiming each type of bodilymental divergence seem contradictory – one emphasizing strength and connection, the other weakness and isolation – it can therefore make sense for an individual to claim both, in different contexts.

To summarize, drawing on Dorcas’s case and that of Akugiziibwe, discussed earlier, where the state was involved, for example in legal hearings and dealings with local councils or government programmes, obulema/disability-based language was more likely to be felicitous. This was why Dorcas presented her case to Mugisa, a state representative, as disability discrimination, which is clearly outlawed. Where claims were directed towards people with whom one regularly shared social space, particularly family or neighbours, the relational language of omuceke/weak person might be more appropriate. Akugiziibwe’s everyday gifts of food from neighbours were a good example. She did not, generally, have to request these gifts: they were simply offered to her during visits to neighbours’ homes, which were a regular and expected part of female sociality in her village, underpinned by the shared orientation to supporting abaceke (weak people) who were present in one’s social space.

However, both discourses also face constraints within their appropriate settings. Obulema/disability-based claims must be carefully pitched to fit within the codified categories of legislation. After hearing the accusations that Dorcas was the real aggressor and had threatened her neighbours, Mugisa warned her that even if she brought lawyers to represent her, it wouldn’t help if she was in the wrong: ‘You will be helped when it is really true that you have been treated unfairly.’ This approach relied on what Friedner et al. call ‘category work’ (Reference Friedner, Ghosh and Palaniappan2018), a form that is closely related to the postcolonial nature of the Ugandan legal system. It relied on the individual fitting themselves and their bodilymental experience into an established framework over which they had little or no influence. This could be difficult when the framework did not recognize the individual’s positionality, as it did not for Dorcas’s gendered experience, in the face of Mugisa’s normative statement of patrilineal inheritance.

The omuceke/weak person discourse, meanwhile, required a substantial history of social enactments (see Sneath Reference Sneath2006) between involved parties for the obligation towards an omuceke to produce experiential force. Where this interactional history was not present, such claims could fail. As Dorcas’s case shows, the effects of earlier self-presentations can also bleed over into different settings, closing down possibilities of alternative claims, as when her neighbours rejected her characterization as omuceke. Claiming to be ‘weak’ and to therefore deserve redress was a powerful tool, but it required one’s audience to concur with the characterization as ‘weak’, both in terms of socio-bodilymental assessment and in relation to whether the necessary relationships linked the parties.

Where the appropriate interactional history is not present, being identified as omuceke may simply mark one out as physically weak and socially isolated, which in combative arenas conceptualized as contests of strength (such as land disputes) can have dangerous consequences.Footnote 22 Dorcas likely chose to emphasize her obulema/disability-related connections during her hearing for this reason, even though most of her audience were family and neighbours. And as her example shows, it was possible in some circumstances to use the language and connections of obulema to act on personal relationships: doing relational work, rather than ‘category work’, by demonstrating greater political power within a setting permeated with age, gender and wealth-related inequalities.

My research demonstrates the ability to call upon obulema-mediated connections to be unevenly distributed, with certain groups of people with disabilities more able to mobilize connections to representatives of the state. Dorcas could do so because of connections to councillors for people with disabilities through the local union of blind people, the oldest and best-resourced disability organization in the area. By contrast, Akugiziibwe’s belonging within the category ‘people with disabilities’ was precarious, as reflected in her weaker connections to the disability-related infrastructure of the town. She was evidently an omulema (a lame person) because she had trouble walking due to partial paralysis. However, as she had never learned to count, she was not considered capable of running a business and consequently remained peripheral to the OPD she belonged to, Tusobora. Her socio-bodilymental circumstances could not be accommodated within the existing infrastructure, closely focused as it was on entrepreneurship, and she therefore did not have the close connections with government and development infrastructure that are the hallmark of ‘omuntu owaina obulema’ (a person with disability). While the meaning of obulema had been expanded to encompass Dorcas and the councillors for people with disabilities who lived with visual impairment, the practical distance between the disability infrastructure and people living with impairments thought to affect the mind and cognition, like Akugiziibwe, offered them no opportunity to develop a similar association with state and legal protections.

Access to discourses and inequality within disabled communities

With this article, I do not intend to argue for the correctness of one approach to bodilymental difference over another. My analysis suggests that different discourses of bodymind difference can offer resources for those living with such differences to negotiate social positioning and access to resources.Footnote 23 I combine analysis of how different ways of talking about bodilymental difference invoke divergent logical forms of obligations (with the obulema (disability) discourse entailing bureaucratic depersonalization,Footnote 24 while the abaceke (weak people) discourse draws on personalized connections mediated through intimate histories) with analysis of the relational contexts to which these obligations apply in practice. In postcolonial or neocolonial times, I argue that disability must be approached as produced in interactions between different ways of understanding marked bodilymental difference, with varying temporal and geographical origins. This approach offers a key resource for Disability Studies,Footnote 25 helping us to understand how categorizations of bodilymental difference – including, but not limited to, ‘disability’ – create practical effects in people’s lives and highlighting both the potential for creative manipulation of narratives and the contexts where incoherence between the different approaches might limit actors’ options and contribute to inequalities within disabled communities.

The national and local intellectual history of the categories and of institutions – in this case including Tusobora, community development offices and NGOs – vitally shaped the outcomes these interactions produced in the lives of the people with disabilities I worked with. Even though it translated as ‘disability’, the ways in which the term obulema was used and understood in this research setting did not conform to how ‘disability’ is understood in international instruments such as the CRPD. Rather than a disadvantaged position, it sometimes emerged as a desired status conveying political power through connection to national and international development discourses and resources – even while people with disabilities also undeniably faced discrimination and experienced substantial social and bodilymental suffering. Being identified as an omuceke (weak person) had similarly context-dependent effects, sometimes acting as a route to vital resources and means for understanding the self as a valued and integral part of a relational community (as it did for Akugiziibwe in dealings with her neighbours), and sometimes instead creating vulnerability by highlighting one’s limited options for redress in the event of mistreatment (see Modern Reference Modern2021: 202–33).

Access to the two discourses was also not evenly distributed, as they are tied to postcolonial and neocolonial infrastructures and resources riven with inequalities. Obulema/disability-related arguments are largely out of reach of people living with certain types of impairment, particularly those considered to affect the mind or cognition, because the concentration of disability-related resources in entrepreneurship-based programmes meant that such people were liable to be ‘dropped’ from OPDs through progressive exclusion from the organizations’ activities. This meant both that they were less likely to have the kind of practical links to councillors that Dorcas mobilized in her land case, and also that the gradual identification that has emerged in Ugandan society since the 1990s between people living with physical or sensory impairments and the state and development infrastructure did not include them. The omuceke/weak person discourse is often more accessible for this group and can bring benefits for them. However, it does not offer connections to state and NGO resources and is particularly limited in relation to financialized and bureaucratic processes, as its power is rooted in specific relationships, not in the abstract rights and identities that govern the bureaucratic realm of law. While citizenship-based and relational discourses can be used at different times by the same person, doing so requires difficult creative relational work, and the resources for creating this articulation are not equally available to all people living with marked forms of bodilymental difference.

Julia Modern is an ESRC postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Anthropology at SOAS, University of London. She received her PhD in 2022 from the University of Cambridge.