In many places, gambling is taken as a sign of moral decline. Persistent gambling can lead to addiction or a loss of self-control and has the potential to engender serious social problems. This chapter examines gambling from the perspective of Matsu’s ethnography. I locate the Matsu people’s gambling habits in the context of the island’s ecology and society, showing that early on gambling was embedded in the fishermen’s lives. It was elaborated during the WZA era to coordinate with the oppressive and tedious rhythm of a society tightly controlled by the army. I argue that gambling in warzone Matsu was not only a cultural metaphor (Geertz Reference Geertz1973) or a form of social resistance (Scott Reference Scott1985), but also an emotional outlet and imaginative practice by which the islanders escaped, ridiculed, and even and contended with the military state.

Gambling and Fishing

Gambling has been a part of Chinese life for a very long time, both in China itself and in Chinese emigrant societies (Watson Reference Watson1975; Basu Reference Basu1991). Matsu is no exception. Before 1949, the men in Matsu had a tradition of drinking and gambling. Whether after an exhausting day out at sea, or while waiting for the tide, drinking and gambling were diverting ways to pass the time and constituted the main form of male entertainment on the islands. Gambling, unlike the labor of women in the domestic space, was a communal activity. As they drank and gambled, men exchanged fishing information and current social news, and created, demonstrated, and reaffirmed their social connections. A man who did not drink or gamble showed that he had neither money nor power. As a Matsu saying reveals:

No whoring, no gambling: ancestors are dishonored

Yet fishing and gambling are in fact mutually implicated at an even deeper level. The senior boat captains I interviewed, who have closely observed the fisherman lifestyle, all pointed to the fact that fishing is inherently a form of gambling. Fishermen are different from farmers who work the land; out at sea, they must confront a host of unpredictable factors, such as ocean currents, wind direction, weather, and so on, all of which can change on a dime. Fishermen not only have to be highly adaptable; they must also be resolute and fearless in the face of danger. Gambling involves a high degree of luck and a “winner take all” mentality that is closely complementary to the fishing experience. For this reason, gambling was more than just entertainment; it was also a training ground (Chu Reference Chu2010: 267), and a way of cultivating bravery and daring in fishermen.

When a comparison is made with agriculture, the connections between gambling and fishing become even clearer. Engaging in farming requires land, and it relies upon a farmer’s patience during lengthy periods of cultivation before crops can be harvested. Preservation of property and harvest from year to year is the main method of building wealth in an agricultural society, which lacks the possibility of sudden windfalls. Fishing societies operate very differently. Fish multiply in the sea without having to be cultivated, and catching them depends not only on skill, but also on luck. When the opportunity arises, one must quickly “grab as much as one can” in order to have any chance of an “unexpected windfall.” Gambling, therefore, is inherent in the fishing livelihood.

Indeed, on such far-flung islands where one had to struggle with the sea for an unpredictable livelihood, life was more dangerous than in an agricultural society. Anyone who was not brave enough to take substantial risks was unlikely to achieve a breakthrough. This notion is reflected in the Matsu saying:

Better to give birth to a prodigal son than a fool.

Although a prodigal son may admittedly squander away the family fortune, his risk-taking behavior also demonstrates that he can tolerate danger, think quickly, and seize an opportunity when it arises. In contrast, a “foolish son” only consumes a family’s assets and is often caught off guard by unexpected events.

However, since uncontrolled gambling can clearly be ruinous to the family, the Matsu people also emphasize:

In either whoring or gambling, you have to take your own measure.

This expression indicates that in both gambling and in illicit sexual relations, one must first be certain of one’s own limits. Again, the point is not to forbid gambling, but rather to achieve a balance so as not to destroy oneself. In sum, gambling represented the adventurous or even audacious character of the islanders. It was not only the main entertainment or social activity for fishermen; the luck, skill, and inherent spirit of risk that it entails also capture what men needed to equip themselves when facing the perils of the capricious ocean.

“Gambling is the Origin of All Vices”

Perhaps owing to worries about people gathering together and causing trouble, or concern about fostering addiction, the army detested gambling from the start. Nearly every year, Matsu Daily reported on the ban on gambling and the arrest of gamblers. A 1959 article already announced strict punishments for gambling:

Any civil servant who gambles will be dismissed from his position, and is banned from taking up a government post in the future. Military officials will be dealt with severely under military law.1

In order to rid Matsu of gambling, the WZA held endless meetings to discuss the problem of “how to eradicate gambling.”2 A 1969 decree entitled “Implementation of a complete gambling ban,” stated that government employees and teachers caught gambling would not only be dismissed, but also that their work unit supervisor would be given a first level demerit. If common people were caught gambling, businessmen would be forced to close their businesses, while fishermen would be kept off the sea for a period of a week to a month. Others would be punished according to the specific circumstances with forced labor, jail time, or fines. Often, the newspaper would publish the names of offenders along with statistics about their professions. For example, a 1972 Matsu Daily article recounts that police had apprehended:

Fifty-six participants in a gambling ring, including two government officials, twenty-six businessmen, fifteen fishermen, three visitors, and ten women.3

What is worth noting in this report is the appearance of government officials and women as gamblers, a subject that I will revisit in the next section.

Nearly every year the police would publicly burn gambling paraphernalia, and the WZA chair would be at the scene to personally supervise and express how seriously the authorities viewed the issue.4 The authorities’ attitude reveals the state’s deep anxiety about losing control over gatherings of locals. Despite their intense efforts, however, the official ban on gambling had only a limited effect.5 As Matsu Daily reported:

Yesterday at 2:30 PM, county police and other officials participated in a burning of gambling equipment at the Shanlong harbor. …Although officials have put a strict ban in place…evil still persists in the face of good, and addicted offenders have continued their old ways, in disregard of the law.6

In this situation, authorities could only implement increasingly harsh laws. For instance, the importation and sale of books about gambling and articles that could be used for purposes of gambling (such as mahjong tiles, Chinese dominos, dice, and four-colored cards) were tightly controlled:

1. Importation regulations: Gambling paraphernalia imported through the regular channels will be confiscated without exception, and the offender’s work unit and name will be recorded and investigated.

2. Sales regulations: The county government forbids all stores within its jurisdiction to sell any gambling paraphernalia.7

The WZA also regularly announced new rules and increasingly severe punishments. By the end, anyone who worked for the government—including all office workers, maintenance workers, service workers, and other employees—would be fired immediately if found to be engaging in gambling activities.8 A year later (1983), there was even an announcement that people who were apprehended three times for providing venues for gambling to soldiers would be expelled from the islands and not allowed to come back. The newspaper denounced the behavior forcefully: “Gambling is the origin of all vices.”9

As officials engaged in this cat-and-mouse struggle against local custom, however, gambling became a kind of shared knowledge between officials and locals. While officials thought of every means possible to enforce a ban against gambling, they also used it as a kind of larger metaphor. For example, in an interview that the WZA chair granted a Taiwanese reporter, he told the following story:

Confucius went on a journey but didn’t bring enough money. So he played a game of mahjong with Shakyamuni, Jesus, and Mohammed, hoping to win enough to cover his expenses. But Confucius’s luck was bad, and he kept losing. Finally, his luck turned, and he got a good hand that included the four directions [and a red tile], so all he needed was another red tile [to make a pair] to win. But then he had a second spell of bad luck, and after several rounds he still hadn’t obtained the needed red tile. The moment he decided to just play the red tile he had in his hand, he received another red tile, but by that time it was too late to win. Confucius was very disheartened. Zilu [Confucius’s student] said: “Having received the four directions, he hoped for another red tile, but as soon as he played his first red tile, of course he lost!” The WZA chair recounted this story, and then added the conclusion: That red tile with a “中” in it represents the “Republic of China.” It’s like a trump card. You can see from this how important the place of China is in the world.10

In the story, Confucius is unlucky, and he does not manage to win any money. When his luck finally changes, he is able to collect tiles for the “four directions,” along with a “red tile.” If he can collect a second red tile, he will win. Unexpectedly, in a moment of carelessness, Confucius gives up his red tile and ruins his potentially winning hand. To educate people, the WZA chair used the “red tile” as a metaphor for the Republic of China, demonstrating that mahjong had already become a form of shared knowledge for the government and locals, as well as a medium for communication.

Lightening the Drudgery of Military Rule

In contravention of the government ban, gambling during the military period extended to all walks of life, and its significances multiplied.

Killing Tedium

“The harder they tried to catch us, the more we gambled” (zhuade yuejin, dude yuexiong), many Matsu residents said. Moreover, while in the past it was mainly fishermen who engaged in gambling, the practice now spread beyond any specific group. Even government officials and teachers began to participate during the WZA period. Matsu Daily’s reports of repeated government orders regarding civil workers show how much of an issue it was. Workers at the Matsu Distillery, the Regulation of Goods Department, and the publishing office of Matsu Daily were caught gambling and named in the newspaper. Yet despite constant government threats, as well as severe punishments including dismissal, people continued to gamble. A man who worked for the Matsu Electric Company recounted the situation at the time:

Back then, we never put away our office mahjong table.11 When the lunch break began, everyone would rush to the table to get a spot. In order to keep a seat, some even skipped lunch completely.

“Why were people so crazy about gambling?” I pressed.

I don’t know. It felt like that was the only way we could get through the day.

It seemed as if only by playing mahjong could one alleviate the boredom of civil service under military rule and make life bearable.

By examining the Supply Cooperative, we can go a step further in understanding the connection between the drudgery of life under military rule and gambling. The Supply Cooperative was a special work unit under the WZA that managed the circulation of supplies within the islands. Its head, deputy head, and section chiefs were all appointed by the military authority, while Matsu locals were employed in subordinate positions as ordinary personnel. Thus, the Supply Cooperative was partly a military entity: at the beginning of each day, workers raised the national flag and did morning exercises before beginning work. Even today, at the old site of the Supply Cooperative, one can see the flagpole towering over the middle of the complex (Fig. 4.1).

Fig. 4.1 The main building of the Supply Cooperative

The Supply Cooperative was responsible for regulating all the important supplies on the islands. Aside from rice, which was controlled directly by the military, all of the goods necessary for daily life such as wheat, sugar, different kinds of alcohol, and construction materials like steel bars and concrete had to be purchased from the Cooperative. One might say that the Supply Cooperative was an enormous warehouse (Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2 The spatial layout of the Supply Cooperative

Work at the Supply Cooperative took place nearly around the clock. In addition to keeping regular working hours, the warehouse also had to be guarded at all times. If supply ships from Taiwan arrived, there had to be workers to go to the docks to receive and unload the goods. Consequently, workers took turns working the night shift, and slept inside. Each worker was expected to work at least one night-shift per week, and often more. The Supply Cooperative had its own kitchen, which prepared three meals a day for the personnel, and staff members slept in the office building. Table 4.1 shows how the staff spent their days and nights.

Table 4.1 Daily Schedule of the Supply Cooperative

| Time | Activities |

|---|---|

| 7:30 AM | Breakfast |

| 8:00 AM | Flag Raising and Morning Exercises |

| 8:30-12 PM | Work |

| 12:00-1:30 PM | Lunch and Rest |

| 1:30-3:30 PM | Work |

| 3:30 PM | Outdoor Exercise |

| 5:30 PM | Dinner |

| 6:00 PM | End of the Shift, or Additional Nightshift |

Personnel at the Supply Cooperative were required to arrive before 7:30 am to eat breakfast together, raise the flag, do morning exercises, and work until the afternoon. After dinner, some workers could go home, but many had to stay on for a nightshift. In order to break up the tedium, the head of the Cooperative included half an hour of rest in the day, usually for outdoor exercise such as basketball games (see the two basketball nets in Fig. 4.2).

Still, this dull, monotonous lifestyle was alleviated by many secret opportunities for different forms of gambling. For example, during the noontime rest, some workers would place small bets over cards or chess. At 3:30 pm, they would make bets over basketball games. There were more chances in the evenings, when they could play mahjong together. The air-raid shelter behind the Cooperative was a paradise for workers. They would run an electrical wire into it and hang lights to help pass the endless night. After an intense night of playing mahjong, however, they would often find the electrical line cut the next morning—a warning from an unhappy commander. The next night they might resist the temptation to play and go back early to sleep.

How the workers turned the officially approved pastime of “basketball playing” into “basketball betting” right under their commanders’ eyes is fascinating. Figure 4.3 shows how it was was done. The painted restricted area had nine positions; once everyone got into position they would dribble a few times, and then with meaningful glances, they would start to bet. Frequently four people would play together, sometimes with each person taking ten shots per turn and the highest points determining the winner. The more common way of playing was for each player to take turns making single shots. If the ball did not go in the basket, the person would remain in place. If it did go in, the person would advance from position 1 to 2 to 3 to 4, and so on. The person who made it to position 9 would win, and the rest of the players would pay up according to their position, owing 100, 200, or 300 Taiwanese dollars. The monotony of life in the Supply Cooperative was brightened by these different forms of gambling.

Gambling Goes to the Graveyard!

Occasionally, when the government crackdown was especially severe, workers would no longer be able to gamble in their offices. When that happened, people would find hidden spots on the island or deserted pigpens where they could gamble unobserved. For example, a graveyard upon a hillside near Ox Horn became a gathering place for gamblers. The ground that had been leveled for the cemetery was a convenient place to lay out their games. It is said that every day at noon, the area would be packed with government workers on their daily break, throwing dice until they had to return to work at 1:30 pm. The dense mountain vegetation helped conceal their activities and kept them from being discovered. Gamblers would also post lookouts. If a civil or military policeman caught wind of what they were doing, they could immediately flee into the forest.

In fact, the police themselves also gambled. In order to understand how this occurred, I talked to several people who had been police officers during the WZA period. One older man who had been a police officer from 1953–61 mentioned that a coworker whom he liked very much had been fired after he was caught playing mahjong. He said that he himself had been enticed into playing cards while patrolling the streets of Shanlong and had received a demerit at work. It seems that even police officers had difficulty avoiding the temptations of these games. I finally met a respectable older gentleman in Ox Horn who said he had never gambled. Still, he told me that when he worked as a police officer in the 1970s, someone notified him about a group of people gambling on a hill near Ox Horn. He went to arrest the culprits but was shocked to find that his own mother was one of the gamblers. Panicking on seeing her son approach, she fell while attempting to flee. Distressed and embarrassed, he hurried over to help her up and told her, “Don’t run, you can take your time.” Subsequently, someone else reported that people had gathered in Fu’ao and Shanlong to gamble; when he went there, he ended up arresting two of his own uncles. Frustrated at having to keep arresting his relatives, he applied to be transferred to work in the Household Registration Bureau.

Under the Table, Inside Tunnels

It wasn’t just government employees who gambled; given half a chance, ordinary citizens also took part. People especially enjoyed gambling during civil defense training. As they told me without any qualms:

An official would be up on stage with spit flying as he held forth about how to take care of our firearms and how to defend ourselves against communist spies, and we’d all be sitting there playing Chinese poker, dealing the cards under the table.

Military exercises presented even more opportunities to gamble. The long, meandering tunnels on the islands, where they would not be seen by their commanding officers, were a haven for gamblers. As one informant told me:

We could gamble even if we had only ten or twenty minutes. If we were pressed for time, we’d deal two cards and go by straight value. If we had a little more time, we’d deal four cards and go by pairs. There’s always a lot of flexibility in gambling.

Those in the teaching profession were no exception. Some teachers would hide in a corner of a school library to gamble. They would arrange to meet ahead of time, and if they heard footsteps approaching, they would immediately cover the mahjong tiles with a cloth, and slump against the table, pretending to nap over their books. A storage house located at the edge of the school campus was also a good site, as it was rarely frequented and filled with plenty of objects to obstruct the view of anyone who happened to pass by.

Women and Dice

During military rule, women involved in selling goods and services to the soldiers would also often gamble, particularly those who opened shops to do G. I. Joe business and those who collected shellfish on the seashore to sell. Once they had their own income, they sought opportunities for a little gambling in the middle of their busy days. They often preferred to play dice, since it produced a quick winner and would not take too much time out of their tight schedules. Their body language was particularly telling as they cast the dice, especially those with low dealer’s points if they thought they had a chance to win. They first mumble some words to the dice, put them against their face and say as they rub them: “When a monkey washes its face there’s money to be made” (F. kau se mieng ou tsieng theing). Then they blow on the dice, clutching them to their chest and rubbing them together. When they are finally ready to toss, they cry excitedly: “Four five six! Four five six!” encouraging the dice to land high. In response, the dealer shouts: “One two three! One two three!” hoping to end in a draw. The atmosphere would often get quite fervent and heated, for they knew if they were caught they would be punished by having to sweep the streets, clean out gutters, or even transport human fertilizer; nonetheless, they still sought out their secret games and after a short while would hurry back to work or to home to cook and take care of their families. Gambling was a part of their daily routine.

“They Just Cannot Catch Us!”

“But didn’t the government control gambling strictly and constantly burn the equipment?” I asked. “What did you do if you didn’t have anything to use to gamble?” One of older policemen mentioned earlier told me:

Fishermen would sometimes hide mahjong pieces in the bottom of their fish baskets, and sometimes they’d bring them back mixed in with the fish! With so many fishermen, how could we check them all?

Other interlocutors spoke over each other excitedly:

There were lots of ways to get hold of mahjong tiles. When we went to Taiwan for sports games or shows, each of us would bring back a few tiles. And when we got back to Matsu, we’d put them all together to make a complete set.

You could also hide them in bamboo! You just hollow out the joints in the bamboo and bring them back that way.

Matsu has no natural gas, so it had to be imported from Taiwan. Some people would saw a gas canister in half, stuff it with mahjong tiles, chess pieces, and playing cards, and then solder it back together. Once painted, it was indistinguishable from the other canisters in the pile.

Gambling in these descriptions became an audacious practice by which people imagined themselves escaping the clutches of the state, creating their own rhizomorphic space (Deleuze and Guattari Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987) and time beyond the control of the military. In the fishing period, Matsu islanders gambled with the ocean; now, they were gambling with the state. They endured and contended with military rule in terms of their gambling culture.

Yellow Croaker and Dominos

Gambling also developed into a kind of ceremonial practice in the military period, particularly during the yellow croaker fishing season in Dongyin. Yellow croaker is a lucrative species found along coastal China, with its fishing grounds spreading south towards the open sea; it is prized for its meat, which is as tender as tofu. They migrate in schools, and Dongyin was on their reproductive migratory route, thereby forming an important fishing ground. Yellow croaker came from the southeast to the Dongyin area from April to June each year, making up the main fishing season for this variety in Matsu (Z. Chen Reference Chen2013:102). Since the 1980s, however, the species has mostly disappeared from the area because of over-fishing.

Before its depletion, the fishermen of Dongyin had a long tradition of catching yellow croaker. Local elders said that earlier in the spring fishing season, fishermen from costal China would come to fish and sell their catch to the mainland. After the separation of the PRC and the ROC, the fishermen of Dongyin were limited to selling their catch to the soldiers on the islands. When supply exceeded demand, they could only resort to drying the surplus fish. In the late 1960s, some Taiwanese ships with cold storage sensed a business opportunity and began to come to Dongyin to purchase fresh fish. Finally, the Matsu Fishing Association came to a negotiated agreement with the shipping companies, according to which they had to place competing bids and guarantee that the winner would buy the entire catch at a set price, irrespective of how much fish was caught. Thus, when the fishing season was good, fishermen could make quite a bit of money. At that time, when the fishing industry operated on cash transactions, catching yellow croaker could mean a welcome windfall. Beginning in 1968, fishermen from across the islands of Matsu came to Dongyin in pursuit of this fish. Before leaving, they had to undergo three days of ideological training in which they learned about the “savagery of the communist bandits” (gongfei baoxing) before being allowed to prepare for their journey. When they set out, officials would come down to the wharf to send them off, setting off firecrackers to wish them a successful return.12

Fishermen said that yellow croaker would rise close to the surface during high tide, and so were relatively easy to catch. The high tides on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar calendar were the most anticipated fishing days for yellow croaker. During the breeding season, the air bladders of the fish vibrate and let off sounds that attract members of the opposite sex. In a particularly crowded school, the noise can sound like boiling water or wind blowing through pines (J. Liu and Qiu Reference Liu and Qiu2002). When there were few fish detectors to locate the fish, fishermen would often rely on the sound of the school to estimate its size. There is a common saying which is used to mock overly talkative people in Matsu. It alludes to the way in which the fish give themselves away with their own noises: “the Dongyin yellow croaker is betrayed by its own mouth” (F. toeyng’ ing uonghua khoeyh tshui hai).

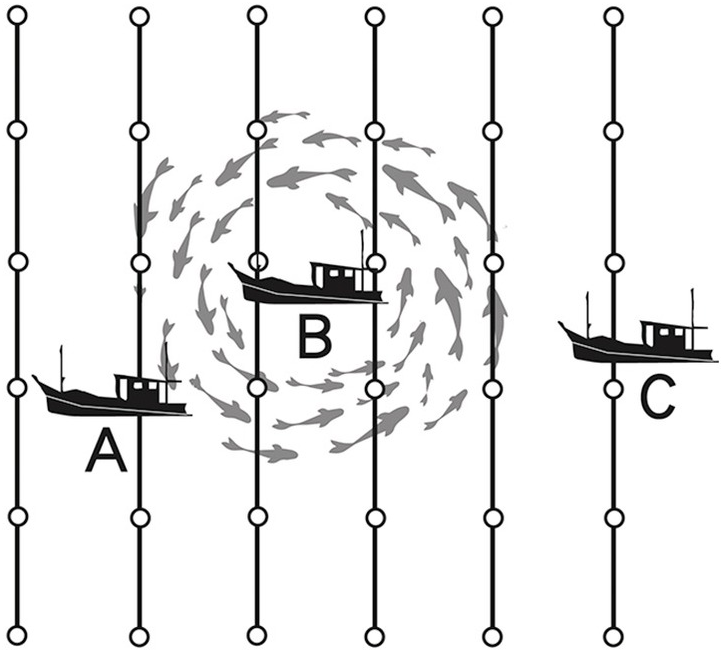

Just because the croaker made revealing noises did not mean that every fishing expedition was successful, however. Even if a captain was skilled at determining the location of the fish from their sound, there was also the question of unpredictable weather and tides, along with other unforeseen factors, so that even the most experienced captain could not guarantee a catch. All the boats went out at the same time and cast their nets in the same vicinity, yet some returned with a good catch, while others barely broke even. One highly experienced captain from Dongyin told me that when the yellow croaker gathered and made a lot of noise, many boats would arrive in the area. But where exactly the fish were at any moment was difficult to discern, and so catching them was a matter of luck (see also Q. Chen Reference Chen2009; Yan 1977). He drew a picture to explain (Fig. 4.4). Boat B is the most fortunate, since its net is cast right in the midst of the school of fish, and so it returns with a full catch; boat A is a bit too far to the left, but it likely still makes a decent catch; but boat C is too far too the right to have much hope of catching anything.

Indeed, the Dongyin fishermen say that whenever they caught yellow croaker, it was like “hitting the jackpot,” and “the excitement of the chase was just like gambling.” During a successful fishing expedition, “the fish floated on the surface of the water like chunks of ice you could walk on” (Q. Chen Reference Chen2009).13 Chen Qizao, a fisherman from Tieban, Nangan, described a big catch:

When luck was on your side, you could bring in 20,000 jin in one net, so much that you couldn’t even fit it all on the boat and you had to shorten the net and let some fish go free! The Taiwanese merchant ships could only carry 200 metric tons of fish, and once they weighed off that much on their scale, the rest got dumped back into the sea!14

The Dongyin boat captain mentioned above also told me that once when he went out in a pair trawler to fish for yellow croaker, he caught 40 tons of fish. “I spent a whole day raising the fish out of the water, that’s how much there was!” He decided to steer the boat directly to Keelung Harbor in Taiwan to sell the fish and made NT$4,000,000 in one go. He continued:

Captain: That night, the crew celebrated by going out “drinking with girls.” At that time [around 1980], it cost NT$100 to hire an escort. You know how much the crew gave her?

Author: How much?

Captain: NT$10,000!

Knowing how extravagantly a yellow croaker catch was celebrated in Taiwan, it is unsurprising that when the fishermen returned to shore they held big gambling parties. Either to test their luck once more or to celebrate a good catch, the fishermen who caught croaker usually gambled heroically. They bet extravagant amounts and were indifferent to loss: the real purpose behind their gambling was display, and to show off rather than to consolidate their earnings.

During the yellow croaker season, fishermen liked to play Chinese dominoes (the locals call it pi peou), which was usually played during the Lantern Festival, the biggest festival on the islands. The ceremonial atmosphere of the croaker catch is therefore significant. During the game, the dealer hands out four tiles to each player, and the players lay them out in two pairs to compare their values with the dealer in fast-paced rounds. Although there are only four players in any given game, others could also place stakes on any of them being the winner. During the catch season, the tables would be crowded with onlookers. There were at least three layers of participants at each table: the people actually playing the game formed the closest ring, the second ring was made up of those taking stakes in the game, and the third ring was observers standing on stools, all forming a noisy excited crowd. There was no limit on bets: a lot of money was quickly won and lost in each game, and the atmosphere was heated and charged with excitement.

The games of Chinese dominoes during the croaker season could be seen as a ritualistic activity. Precisely because of this ceremonial nature, the military tended to look the other way and not shut the games down. But because of the high stakes, fishermen would sometimes gamble away an entire season’s hard-earned income. At the time, there was a popular saying:

You cry when you catch croaker, and you cry when you don’t.

(F. uong’ ua huah ya thie, mo huah ya thie)

The expression describes the difficulty of catching yellow croaker, and the misery of easily losing it all at the gambling table.

By the time the season was over, many had lost nearly all of their earnings (Q. Chen Reference Chen2009). A man from Ox Horn, the son of a fisherman, told me that when he was young his father spent two months in Dongyin each yellow croaker season, yet he always came back with empty pockets. I asked him why his father continued to participate if he didn’t earn any money from it, and he told me: “That’s just part of being a fisherman, he couldn’t not go.” Owing to depletion, the yellow croaker faded into the annals of history after 1985, but elders still remember the season and their Chinese domino games as though it were yesterday.

Conclusion: Gambling with the State

Anthropologists have discussed the significance of gambling from different perspectives. Earlier it was considered a metaphor for other aspects of social life (Geertz Reference Geertz1973). More recently, it has been analyzed as a form of symbolic resistance to the state (Papataxiarchis Reference Papataxiarchis, Day, Papataxiarchis and Stewart1999) or as a way of engaging with uncertainty (Davis Reference Davis2006; Malaby Reference Malaby2003). Gambling in Chinese society, especially mahjong, has also received considerable attention. Scholars have elucidated the cultural content of mahjong: notions such as fate, luck, and skill, and how they form analogies and affinities to other aspects of society. For example, mahjong bears a likeness to business adventures among the Chinese migrants in India (Basu Reference Basu1991), while in Taiwan, mahjong “agonistics” and the vibrant political culture were mutually reinforcing (Festa Reference Festa2007). In the twenty-first century, gambling is still very popular in the Chinese countryside: it is a way for the villagers to engage with the authoritarian state and with neoliberalism (Bosco et al. Reference Bosco, Liu and West2009), or for Fuzhounese migrants’ wives it is a way to escape loneliness (Chu Reference Chu2010). It is also, however, a means of contending with the boundaries between old and young, rural and urban, local sociality and state discourse for the people in Enshi, Hubei province (Steinmüller Reference Steinmüller2011).

My analysis, different from previous scholars, examines the changing significances of gambling practices: that is, I discuss how gambling in Matsu developed from a leisure activity for men in the fishing society to an everyday practice of the general population during the military’s reign. During the WZA period, gambling was no longer limited to a particular time, space, or group of people (Basu Reference Basu1991), but extended to all levels of society (from the WZA chair and government functionaries to the lowest rungs of society) and involved both men and women. It could vary from the public dominoes played by fishermen to people hiding cards under the table at civil defense training, and from the ritualistic to the ordinary. That is, it became “a way of life” in Watson’s words (Reference Watson1975: 168). Various forms of gambling corresponded to the life rhythms of different people. Lengthy games of mahjong livened up the dull routines of low-level government workers under the WZA. Rapid dice games could offer a brief respite to women during their hectic days engaging in G. I. Joe business. The excitement and betting involved in Chinese dominoes mimics and re-enacts the risks and festivity of the precious fishing season. These different forms of gambling responded to the social dynamics across all professions during military rule.

However, the reasons gambling proliferated go well beyond its analogies with other social aspects or its role in negotiating the boundaries between the governed and the ruling state, as other scholars have argued. During the years of tedious drudgery that the islanders were expected to endure under the WZA, gambling was a way to give vent to the boredom of routine and to relieve the tedium under an otherwise stifling military rule. Gambling was thus an emotional outlet—a stage for enacting humor, ridicule, and anger, and an imaginative practice with which to evade the iron control of the military.15

Nevertheless, the people of Matsu were still forced to the extremes of the islands—clammy tunnels, bleak graveyards, and deserted pigpens—to find room to breathe. As we can surmise, their rise against military rule was imminent.