Introduction

Through workforce mobility and a globalised economy, organisations must manage employees from more demographically diverse groups compared to those in the past, with organisations now desiring access to obtain the benefits of a diverse workforce, such as creativity and innovation, while balancing the potential for tension, conflict and miscommunication (Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013; Syed & Kramar, Reference Syed and Kramar2009). Furthermore, workplaces are more intertwined with interpersonal relationships and social interactions; there is an increasing requirement for diversity management to look beyond more recognisable surface-level attributes such as ethnicity and to encompass less-visible individual differences, such as upbringing, lifestyles, family status, disability, education, or physical attributes (Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013; Hope Pelled, Ledford, & Albers Mohrman, Reference Hope Pelled, Ledford and Albers Mohrman1999; Rupert, Blomme, Dragt, & Jehn, Reference Rupert, Blomme, Dragt and Jehn2016). Where traditional diversity management aims to have all employees working well together while achieving organisational objectives, there is a tendency to favour the mainstream, and current practices have been unable to ‘alleviate the ongoing under-representation of ethnic minorities, women and other disadvantaged groups’ (Syed & Kramar, Reference Syed and Kramar2009: 644). By recognising that individuals may vary within, as well as between cultures, and broadening to include individual differences, a more mutual benefit can be achieved through an inclusive, socially responsible approach to diversity (Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013; Syed & Kramar, Reference Syed and Kramar2009). To unlock the benefits of a diverse workplace while managing the challenges, organisations now need to empower a more inclusive climate where all individuals can feel a sense of belonging, are fairly treated and are valued for who they are (Harrison, Boekhorst, & Yu, Reference Harrison, Boekhorst and Yu2018; Pless & Maak, Reference Pless and Maak2004).

The tempered radical is acutely attuned to individual differences, providing great potential as a champion of diversity and inclusion within organisations seeking to adopt a more inclusive and socially responsible approach to diversity. Tempered in their approach and yet seeking radical change, the tempered radical were introduced in the seminal work of Meyerson and Sculley (Reference Meyerson and Scully1995) as powerful change agents with a subtle approach and a strong inclination towards substantive values such as wellbeing and equality. Their tempered approach makes them less visible as champions of their cause; they can be hidden in plain sight. The tempered radical respects organisational objectives and yet identifies as being different in values or identity to the dominant practice or culture within their organisation: they are ambivalent to both. Understanding the experience of being different, rather than seeking compromise, the tempered radical draws together differing views, subsequently promoting respect of individual differences, fostering a sense of belonging and inclusion. Their influence should not be taken lightly; as Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001a) suggests, the tempered radical intends to bring meaningful social change, to make the world a better place, and to amplify positive actions. At the very least, while staying true to their values and identity, these individuals make subtle yet determined approaches to change their workplace for the better. While tempered radicals have been introduced in literature as change agents, this current study recognises their potential to be invisible champions of inclusion with an ability and interest to embrace topics such as background, lifestyles, family status, disability, education, and physical attributes.

The central motivation of this study is to understand how tempered radicals might foster inclusion in the workplace, contributing to management and organisation literature through the development of an inclusion framework that explains the critical characteristics of tempered radicals as they foster inclusion in their workplace. A particularly relevant subject for organisations looking to take advantage of their increasing diversity, arising through the changing workplace or the recognition of diversity non-culturally, as individual differences (Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013).

Purposefully selected as a setting for this study, manufacturing organisations provide a richly diverse and rapidly changing environment which offers the advantage of having people working closely together and relying on each other to complete their own work tasks (Alat & Suar, Reference Alat and Suar2019). Furthermore, recent evidence suggests manufacturing organisations are facing changing paradigms that now include the desire for collaborative product and process design, and the convergence of humans, technology and information (MBIE, 2018). Manufacturing is often overlooked in research, yet the environment of heightened change and close collaborative teamwork serves to incubate and highlight hidden activities by individuals to foster inclusion, making it an ideal stage to conduct this research on inclusion. Earlier studies of tempered radicals have incorporated voices from only managerial levels in information technology and financial services organisations (Meyerson, Reference Meyerson2001a), although as Smollan and Griffiths (Reference Smollan and Griffiths2020) note, organisational culture has an implicit relationship to identity, and identity is best observed at different levels of the organisation. Manufacturing's traditionally top-down hierarchical organisational structure provides yet another advantage for this study, making it easier to seek participants from clearly defined levels of operational, supervisory and managerial staff. This will allow for a multilevel approach drawing out business arguments and equity arguments, thus helping to inspire efforts towards equality and inclusion in organisations.

We next present literature that reveals the tempered radical as a resilient change agent, familiar with managing the tensions between their personal and professional identities through an often-invisible struggle, making them well placed to foster inclusion. The methodology section reveals a series of qualitative, narrative interviews conducted with participants working across different organisational levels within manufacturing industries. The findings and discussion show contribution to knowledge through the development of the tempered radical's inclusion framework, depicting the characteristics that explain how tempered radicals foster inclusion in their workplace.

Literature review

The construct of the tempered radical was first introduced by Meyerson and Scully (Reference Meyerson and Scully1995) to define those who enjoy their work and are committed to their organisations, even though something important to them, for example, their values or identity, makes them feel ‘at odds with the dominant culture of their organisation’ (Meyerson & Scully, Reference Meyerson and Scully1995: 586). Tempered radicals balance being successful in their organisation while being true to themselves, their values and identity, and their personal guiding principles determining what is good and worthy (Meyerson, Reference Meyerson2008; Rahn, Soutar, & Lee, Reference Rahn, Soutar and Lee2020). Identity theory suggests how ‘self’ can influence attitudes, behaviour and the execution of operational activities, as every human has a sense of ‘self’ that constructs, interprets, organises and synthesises experiences (Marshall, Reference Marshall1995; Yolles & Di Fatta, Reference Yolles and Di Fatta2017). Our self-identity is a social construction; our thoughts, moral judgements, motivation and the ways of relating to others; whereas our public identity frames how we externally express experiences, restrain self and maintain harmony with social context (Olson & Maio, Reference Olson, Maio, Millon, Lerner and Weiner2003; Smollan & Pio, Reference Smollan and Pio2017). The tempered radical successfully tempers their self-identity and their public identity; they are ‘committed to their organisations and also to a cause’ (Meyerson & Scully, Reference Meyerson and Scully1995: 585). This helps the tempered radical to quietly celebrate difference so as not to alienate others, adopting an unofficial partnership with their organisation to achieve social change such as wellbeing and equality (Kelan & Wratil, Reference Kelan and Wratil2018; Kirton, Greene, & Dean, Reference Kirton, Greene and Dean2007; Meyerson & Tompkins, Reference Meyerson and Tompkins2007; Walton & Kirkwood, Reference Walton and Kirkwood2013).

It is the tempered radical's personal interest in social change that encourages their proactivity, enabling them to work as social activists, pursuing change for mutual benefit with resilience when their direction may not align with organisational norms (Bajaba, Fuller, Simmering, Haynie, Ring, & Bajaba, Reference Bajaba, Fuller, Simmering, Haynie, Ring and Bajaba2022; Briscoe & Gupta, Reference Briscoe and Gupta2016). The tempered radical's identity takes on a dual nature, defined by Meyerson and Scully (Reference Meyerson and Scully1995: 588) as a ‘state of enduring ambivalence’. Rather than settling with a state of balance or compromise, Meyerson and Scully (Reference Meyerson and Scully1995) describe the tempered radical's ambivalence as being a source of strength and vitality, a key asset of the tempered radical. Their ambivalence respects differing views, enabling a more inclusive approach compared with seeking compromise – which seeks a middle ground that may dilute the value either direction may offer (Meyerson & Scully, Reference Meyerson and Scully1995). Through their ambivalence, the tempered radical seek success for the organisation while at the same time modestly challenging the usual order of business (Kirton, Greene, & Dean, Reference Kirton, Greene and Dean2007; Meyerson & Scully, Reference Meyerson and Scully1995). In Walton and Kirkwood (Reference Walton and Kirkwood2013) study of environmental entrepreneurs as change agents, these ‘ecopreneurs’ are likened to tempered radicals as they bring radical change in support of their personal interest in sustainability at the same time as being realistic about the everyday requirements of running a profitable business. Ambivalence is illustrated through the construct of holism, which according to Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt, and Pradies (Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014: 1465), is the ‘complete, simultaneous, and typically conscious acceptance of both opposing orientations’. Holism considers win-win outcomes and allows both directions to be fully embraced, enabling growth in understanding and an appreciation of difference. According to Ashforth et al., (Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014), holism facilitates adaptability and enables ambivalent individuals, such as the tempered radical, to deliver change. Ashforth et al., (Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014) and Luo, Lui, Liu, and Zhang (Reference Luo, Lui, Liu and Zhang2018) further suggest that wisdom and innovation are linked to ambivalence by bringing in unfamiliar knowledge to the organisation through their outside experiences, identities and values. Ambivalence is, in part, being able to acknowledge and embrace opposing ideas simultaneously and then seek a course of action that compliments both. It is not indecisiveness; ambivalent individuals are proactive; they have a reluctance to simplify, and they embrace complexity.

Guided by this sense of ambivalence, the tempered radical uses a spectrum of change strategies to bring about organisational change. These strategies range from being subtle, incremental and individually driven to more public-facing actions through coalitions (Quinn & Meyerson, Reference Quinn and Meyerson2008). The tempered radicals are named so as they work with a steady approach and yet their subtle strategies can bring revolutionary change. Being tempered in approach has an advantage when personal interests are shared. As Zhu, Restubog, Leavitt, Zhou, and Wang (Reference Zhu, Restubog, Leavitt, Zhou and Wang2020) suggests, individuals who flaunt their moral standing or express indignation at the behaviour of others can obtain a negative response. Badaracco (Reference Badaracco2001) also notes that quiet leaders are said to be modest and restrained and yet able to achieve extraordinary results by utilising a long series of small efforts with interest in righting or preventing ethical wrongs. Offenberger and Luong (Reference Offenberger and Luong2009) concur, explaining that while changes are often seen as the actions of powerful people or dramatic events, the tempered radical has the advantage of operating at any organisational level, not necessarily relying on their position within an organisation to influence change, neither are they necessarily aspiring to hold leadership positions. The tempered radical working in frontline positions has the potential to be a powerful change agent. In a recent ethnographic study, Kras, Magnuson, Portillo, and Taxman (Reference Kras, Magnuson, Portillo and Taxman2021) show how frontline and frontline supervisory Corrections Officers choose to make operational decisions that deviate from policy set at executive levels. Working in quiet coalitions they ultimately disrupted the implementation of policy. As Quinn and Meyerson (Reference Quinn and Meyerson2008) note, tempered radicals may be a senior executive or a board member, they may hold a mid-level supervisory position, or they may hold a junior-level position in their organisation as a production operator. It is the variety of circumstances and backgrounds that add tremendous value to the spectrum of change strategies adopted by the tempered radical. Remarkably, there has been little discussion about tempered radicals in operational to mid-level supervisory positions, an opportunity to be considered in this current study.

Kelman (Reference Kelman2006) suggests the tempered radical has an identity with a strong orientation towards values, aiding a resilient and active evaluation of the workplace process. They draw on their personal interests and life experiences and are aware of the social impact of their influence. Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001a) notes that the tempered radical has substantive values in mind, such as lifting wellbeing, social benefit, and equality – ultimately seeking meaningful change to make the world a better place and to amplify positive actions. Meaningful change arises in a social and collective context of the workplace when work invokes the greater good in terms of societal as well as economic benefits (Bailey & Madden, Reference Bailey and Madden2017; Frankl, Reference Frankl2008; Hackman & Oldham, Reference Hackman and Oldham1976). It is, as Lips-Wiersma and Morris (Reference Lips-Wiersma and Morris2009: 492) define, ‘the subjective experience of the existential significance or purpose of life’. Meaningfulness resonates with the tempered radical; the tempered radical is committed to the success of their organisations and wants to effect meaningful change, to provide benefit for society and to amplify positive actions (Meyerson, Reference Meyerson2008).

While the tempered radical may eye substantive values, the contrasting functional values of productivity, profit and growth reign as the dominant capitalist paradigm of markets, corporations and manufacturing (Boxall & Purcell, Reference Boxall and Purcell2011; Hackman & Lawler, Reference Hackman and Lawler1971; Shaw, Reference Shaw2017). As Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Ehrhart, and Singh (Reference Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Ehrhart and Singh2011: 1234) explain, having different values to the dominant culture of the workplace may actually be a trigger that activates the tempered radical:

‘when belongingness and uniqueness needs are placed in jeopardy … studies show that individuals will engage in efforts to achieve the balance that they seek’.

This notion of belongingness and uniqueness is often featured when discussing inclusion in the workplace. According to Harrison, Boekhorst, and Yu (Reference Harrison, Boekhorst and Yu2018), inclusion is the level to which the individual feels they are a welcome and valued member of the work environment, and an inclusive work environment fulfils the need for belonging and welcomes uniqueness. Similarly, according to Luo et al., (Reference Luo, Lui, Liu and Zhang2018), an inclusive climate is created when individuals from different backgrounds are fairly treated, valued for who they are and included in decision making. It is not unusual for employees to feel at odds with their organisations, and many who do not fit in with its dominant culture may choose to conform or move on to another employer. For some, there is the ongoing struggle of when and how to speak up, and for others, there is a sense of futility or fear (Creed, Reference Creed2003). The tempered radical, however, have the resolve to challenge business-as-usual practices by ‘… creatively destroying current ways of operating while still operating successfully in that business environment’ (Walton & Kirkwood, Reference Walton and Kirkwood2013: 464). The tempered radical wants the organisation to be successful within the marketplace, just in a different, more ethical way.

Kelan and Wratil (Reference Kelan and Wratil2018) note the tempered radical lives with a different embodiment to the norm. Whatever makes the tempered radical different or at odds with the dominant culture of the marketplace or the organisation drives their transformation agendas and provides conflict between wanting to act on those agendas and wanting to fit in (Meyerson, Reference Meyerson2001b). Through the dichotomy that is created between the marketplace and manufacturing and the contrast in values and identity, the tempered radical is activated, leading change agendas driven by substantive values, encompassing agendas embracing equality, inclusion, work-life balance or environmental sustainability. Such as in Walton and Kirkwood (Reference Walton and Kirkwood2013) study of environmental entrepreneurs as change agents, where these ‘ecopreneurs’ are likened to tempered radicals as they bring radical change in support of sustainability at the same time as being realistic about the everyday requirements of running a profitable business.

Manufacturing industries are a key driver of economic success, offering a richly diverse and rapidly changing environment with people working closely together, often relying on each other to complete their own work tasks (Alat & Suar, Reference Alat and Suar2019; Li, Chiaburu, & Kirkman, Reference Li, Chiaburu and Kirkman2017; Morgeson, DeRue, & Karam, Reference Morgeson, DeRue and Karam2010). Individuals are drawn together by the work requirements of the manufacturing organisation, and work has become intertwined with interpersonal relationships and social interactions, particularly more recently through an increasingly mobile and globalised economy (Grant & Parker, Reference Grant and Parker2009; Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013). This combination of a diverse environment, together with heightened change and collaborative work, makes manufacturing an ideal stage in which to conduct research centred on inclusion in the workplace. Manufacturing work has become increasingly completed by teams of employees rather than individuals, formed predominantly with the hope that the output of the team would be more than the combined output of the individuals (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2011; Hackman, Reference Hackman2002, Reference Hackman2012; Lencioni, Reference Lencioni2005; Wageman, Reference Wageman2008) and to capitalise on the synergist effects of collaboration (Banks, Batchelor, Seers, O'Boyle, Pollack, & Gower, Reference Banks, Batchelor, Seers, O'Boyle, Pollack and Gower2014). Today, most organisations understand the value of having a diverse workforce; however, creating an environment where people can celebrate who they are and use their unique talents for both the benefit of society and the organisation is less understood (Brown, Reference Brown2018). Enter the tempered radical, acutely aware of difference, subtle and resilient in approach, and working unnoticed by organisations and as their invisible champions of inclusion.

Research question

This study was motivated by several factors. Firstly, the tempered radical is familiar with managing the tensions arising from being different to the dominant culture of the workplace; it is this experience of difference that make the tempered radical a potential agent to foster inclusion in the workplace. Although literature has recognised tempered radicals as change agents, research has yet to investigate tempered radicals' ability to foster inclusion in the workplace. Secondly, where earlier studies of tempered radicals have been limited to middle and senior positions within services and information technology industries, this study will include participants from all organisational levels, including frontline operational and mid-level supervisory positions. This multilevel approach will help draw out business arguments and equity arguments, helping to validate the value of inclusion in organisations. Thirdly, this study takes advantage of the highly collaborative, richly diverse and rapidly changing employment environment of manufacturing industries. Manufacturing is often overlooked in research, yet the collaborative environment will serve to illuminate inclusion, while the hieratical organisational structures make it easier to seek participants from different organisational levels.

Consequently, to obtain a greater understanding of these powerful and often unseen change agents and their actions influencing inclusion, this current study aims to answer the question:

RQ: How might tempered radicals foster inclusion in the workplace?

Methodology

Theoretical foundation

Business research, the nature of management and business knowledge typically calls for a positivist paradigm with a heavy reliance on experimental and measurable studies delivering causal explanations (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Reference Eriksson and Kovalainen2016). This current study, with a desire to frame the experiences of individuals who are, by nature, less visible, required a different methodology and took guidance through a subjective ontological approach and a constructionist epistemological view and drew on an interpretivist theoretical paradigm.

Narrative inquiry is an interpretive methodology guiding the study of an individual's experiences in the world and the social, cultural and institutional contexts that influence the experience (Clandinin, Reference Clandinin2006, Reference Clandinin2007, Reference Clandinin2016; Daiute, Reference Daiute2013; Kim, Reference Kim2016). To accomplish the aim of this research, narrative inquiry was utilised to collaboratively engage with the tempered radical; interview participants were encouraged to be active contributors, to tell their stories, while the researcher engaged with participants to create a shared understanding. Tempered radicals, by their very nature, adopt subtle strategies and may not be immediately apparent in the manufacturing workplace. Advantageously, the approach of narrative inquirers is to ‘come alongside participants’ (Clandinin, Reference Clandinin2016: 34), put their participants at ease, and inquire into their lived and told stories.

Process

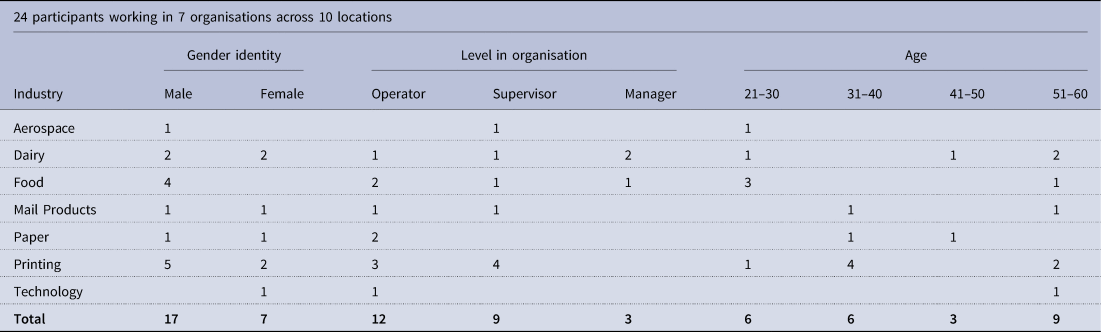

Inclusion criteria captured characteristics required to address the research aim and guided the researcher's judgement for participant selection (Symon & Cassell, Reference Symon and Cassell2012). These criteria were used to screen participants, confirming their manufacturing industries experience, positive sentiments toward their work and workplace, and their approach if they wanted to change popular ways of working or behaving in their workplace. Potential participants would need to indicate manufacturing experience and a subtle approach to changing popular ways of working or behaving in their workplace. Different manufacturing industries and organisation sizes were approached for permission to advertise on physical and virtual sites such as notice boards and company intranets. Participants were then recruited from operational, supervisory and managerial levels and provided with an information sheet to ensure they were sufficiently informed regarding the research and research processes. Twenty-four participants (see Table 1) with a mix of gender, age, and occupations were interviewed through semi-structured interviews conducted either face-to-face or online.

Table 1. Participant distribution by industry, gender, level in organisation and age

Most participants were asked the same questions, although there would be some variation depending on the roles and method or environment where the interviews were conducted. Each interview lasted around 60 min, was digitally recorded and transcribed by the researcher. As Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) recommend, transcriptions and any participant quotations used in this study were kept true to their original nature. Additionally, field notes captured aspects of the interview not included in the recording and transcripts, such as informal observations of both the participants and the surroundings. Within the interviews, participants were first asked to share a little about themselves, starting with their life outside of work. As well as learning more about the participant's backgrounds, basic demographic information was captured during this part of the interview. If not included in the narrative, prompts were given to share values and identity as well as identifying attributes of a tempered radical. Participants were then guided to tell stories of their workplace experiences, particularly around inclusion and equity and their involvement or insights towards change and how they brought about change in their workplace.

Guidance for determining data saturation is often ambiguous, as new data will inevitably add something new, and one interview is rarely the same as the other (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Reference Eriksson and Kovalainen2016). At the research design stage for this study, the guidance of 20–25 participants was tabled, which fell within the sample size suggested by Symon and Cassell (Reference Symon and Cassell2012) for studies of a similar nature. In practice, once over 20 participants were interviewed, transcribed, and thematic analysis commenced, new data useful to the aim of this study diminished. Researcher judgement determined that 24 participants provided data sufficient to meet the aim of this study; data had reached saturation.

Analysis

Thematic analysis of the data supports a rich and comprehensive interpretation through pattern-based organisation and description, involving ‘a constant moving back and forward between the entire data set’ (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006: 86). For this study, themes and patterns of meaning were identified and analysed within the context of the research topic and shaped by the researcher's standpoint, experiences, and epistemology (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013; Clandinin, Reference Clandinin2016). This mutual, collaborative shaping of understanding through the participant, researcher and theoretical frameworks is referred to as a middle-ground approach, allowing theory and empirical research to integrate (Ebrahim, Pervaiz, Ying Ying, & Paschal, Reference Ebrahim, Pervaiz, Ying Ying and Paschal2014; Merton, Reference Merton1968). In this current study, elements of theory and practice were drawn together through two frameworks, firstly Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008) attributes of the tempered radical, and secondly, Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008) spectrum of change strategies. As well as revealing an understanding of the nature of the tempered radical and their approach to inclusion in manufacturing industries, these frameworks demonstrated the credibility and strength of participant selection.

NVivo 12, a computer-assisted qualitative analysis application, was used to evaluate the interviews. This software served to facilitate the analysis process and to support the interpretive and reflexive thinking skills of the researcher (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Reference Eriksson and Kovalainen2016; Silverman, Reference Silverman2017). Themes and patterns of meaning that guided the findings of this study were identified and analysed through several phases within the context of the research topic and shaped by the researcher's epistemology (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013; Clandinin, Reference Clandinin2016). Broadly, across the themes associated with the attributes of tempered radicals, the majority of participants indicated a prominent desire to be successful in the organisation, to fit in. When considering the strategies for change, most of the participants within this theme favoured resisting quietly and staying true to their values and identity, which were guided by their life experiences. These prominent themes and patterns led to the development of categories capturing possibilities of how these attributes and strategies foster inclusion, with, for example, most of the references coded in this category discussing how the participants draw on knowledge gained outside of the workplace, bringing this into the workplace through subtle strategies.

Findings

In this section, the interview data is interpreted and presented through Meyerson's frameworks, shaping understanding through the participant interviews, the researchers and the theoretical frameworks using the middle-ground approach. Tables presented throughout this section present specific examples, themes and categorisation centred on inclusion. First, shaped through participant attributes, the data reveals the subtle signs that indicate tempered radicals. Second, the data reveals examples of participants influencing their workplace through Meyerson's five strategies implementing changes influenced by life experiences, a desire for meaningful change and a balanced respect for their workplaces.

Attributes of tempered radicals

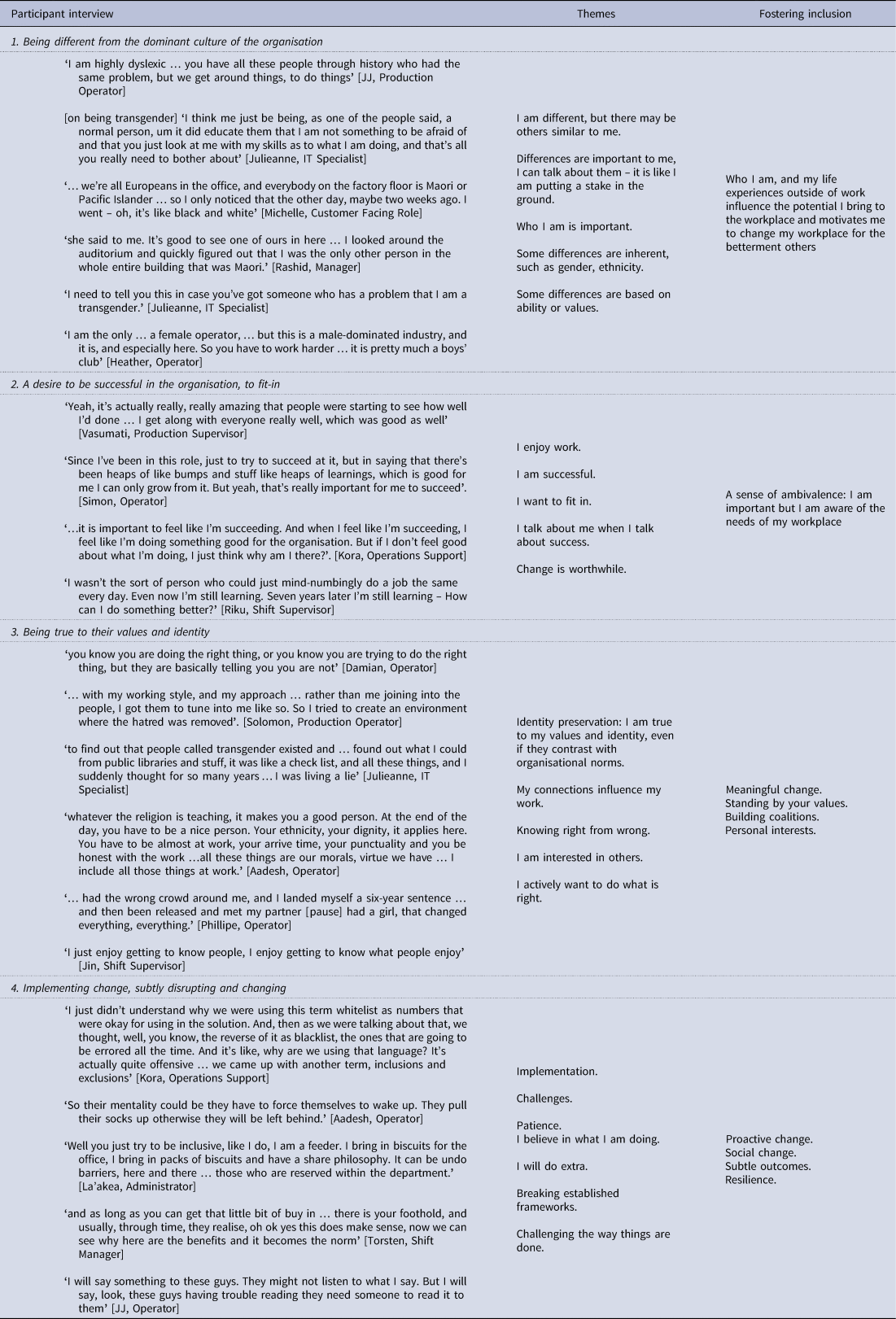

The first theoretical framework employed in this study is Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008) four attributes of the tempered radical (see Table 2). As well as providing an understanding of the nature of the tempered radical, employing this framework reveals the participants of this study exhibiting the attributes of the tempered radical. Used to guide the semi-structured interviews, the framework ensured reliability, consistency, and the replicability of this study. While giving the researcher and participant sufficient freedom to explore a narrative view of experience, the attributes that define the tempered radical were confirmed, without derailing the participant's story.

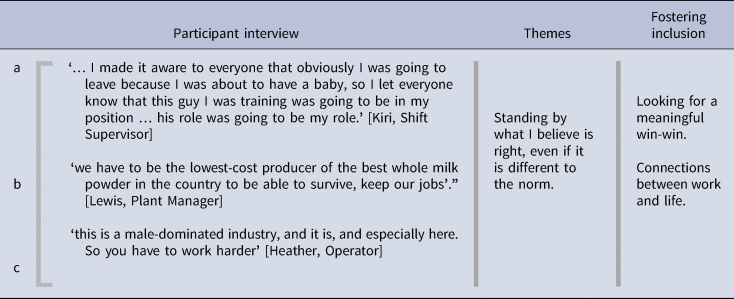

Participants of this study shared practical examples that endorse the attributes of the tempered radical (see Table 3). The first attribute recognises that the tempered radical is different in values and identity to the dominant culture of the workplace. Second, despite the differences with the dominant culture, the tempered radical has a desire to fit in and be successful in the workplace. Third, despite the desire to fit in, the tempered radical chooses to remain true to their values and identity. Fourth, the tempered radical is proficient at implementing change and disrupting or changing the usual way of thinking. Our participants demonstrated a desire to preserve their identity, even if it contrasted with organisational norms. They were motivated by their personal interests and proactive in achieving social change, building coalitions if necessary. They could operate as minority members and yet contribute to radical social changes. The findings confirmed that the tempered radical could be in a variety of positions and levels in the organisation – from operational, supervisory and administrative roles, although in earlier studies, such as Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001a), participants generally came from mid-level to senior-level positions focused on financial services or computer industries.

Table 3. Attributes of the tempered radical – participant examples

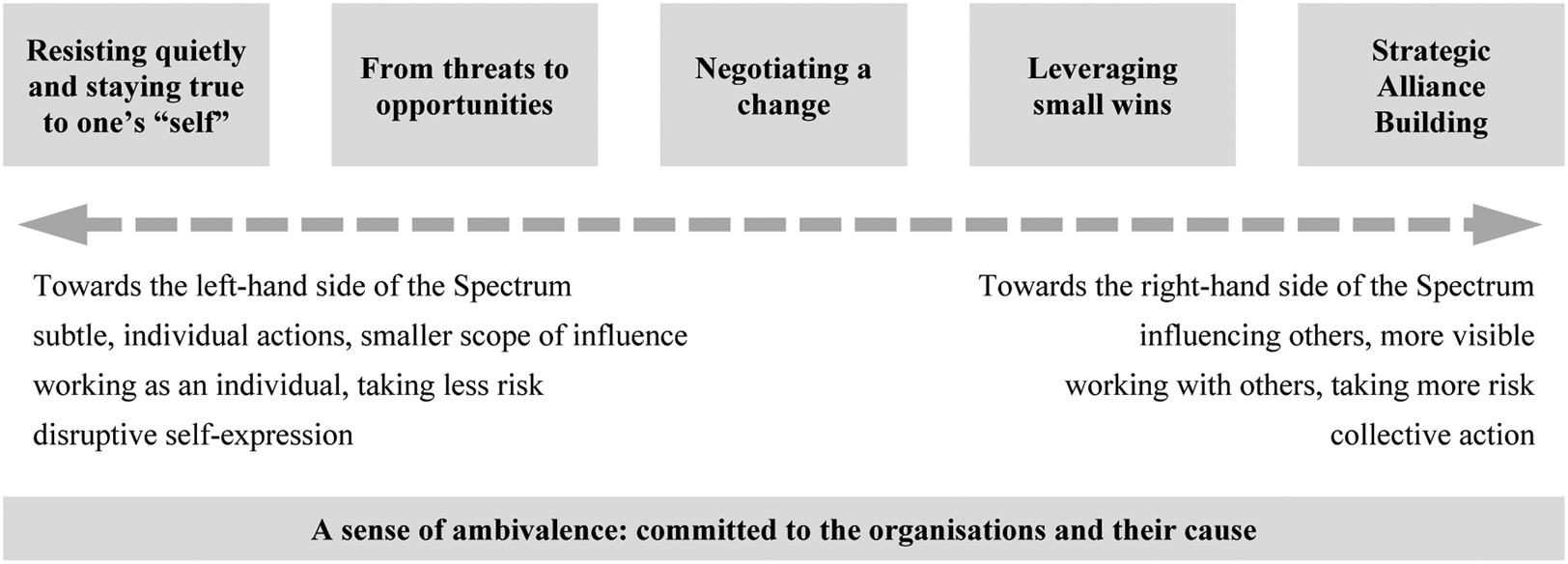

A Spectrum of strategies

The second framework incorporated in this research is the spectrum of tempered radical change strategies (see Figure 1). These are the strategies that tempered radicals use to bring about organisational change, and through these strategies, examples of fostering inclusion were demonstrated. The spectrum, developed by Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008), ranges from strategies that are quiet, subtle, involve few people, and where small wins are used to reduce considerable challenges to a more manageable size. These strategies then gradually increase in visibility to involve more people, become more visible to others. They are described by Meyerson as a spectrum to demonstrate that individuals do not necessarily utilise these strategies in sequential order, and there may be overlap, depending on each situation.

Figure 1. Spectrum of strategies adapted from Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008).

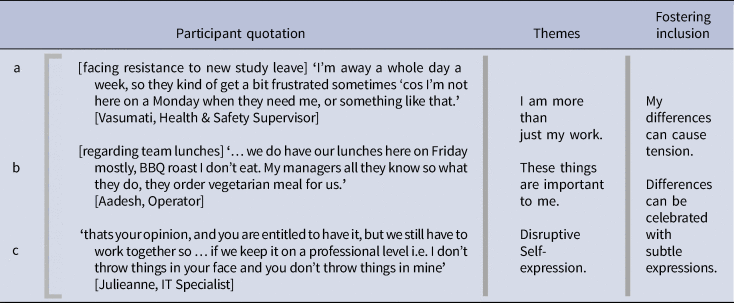

The participants of this current study positively influenced their workplace through less visible strategies, implementing transformation that circles themes of inclusion, influenced by life experiences, a desire for meaningful change and balanced respect for their workplaces. Resisting quietly and staying true to one's self is the essence of the tempered radical, utilising subtle acts of expression such as dress, objects displayed in the workspace, language and behaviour (Meyerson, Reference Meyerson2008). These can all be used as subtle demonstrations to share values or identity and to acknowledge and encourage difference. The approach taken by the tempered radical may be subtle; the change itself may be considered significant or radical.

Vasumati, a participant with ambitions for promotion, working in a manufacturing plant in regional New Zealand, encountered resistance from her peers regarding her approved leave from work to study ‘ … so they kind of get a bit frustrated sometimes’ (see Table 4 Participant Quotation a). However, Vasumati's commitment to her ongoing education is strong, and despite feeling different from her peers, ‘they're all aware that I'm doing it’, Vasumati remains committed to her cause. Her approach to her peers is tempered ‘we don't keep … a secret, but we don't publicise them either. Rightly or wrongly, yeah’. Tempered radicals can foster change in the organisation and, in the process, subtly install an increased awareness of difference.

Table 4. Spectrum of strategies – resisting quietly

Vasumati's experience caused some tension in the workplace and highlighted a potential challenge for the tempered radical: isolation and loneliness (Meyerson & Scully, Reference Meyerson and Scully1995). Similarly, Bajaba et al., (Reference Bajaba, Fuller, Simmering, Haynie, Ring and Bajaba2022) suggest that tempered radicals are concerned that their desire to preserve their identities might lead to social losses such as isolation, and they may be evaluating the extent of risk and likelihood of success for their causes. The tempered radical may be trying to make changes in a community and receive feedback from their peers that change may not be welcome. Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001a) refers to this as disruptive self-expression, noting that others see these displays and then may be encouraged to do the same or resist.

Meyerson's spectrum suggests more visible strategies are called into action involving collaboration with more people, should there be a need. By turning personal threats into opportunities, tempered radicals effectively reframe challenging encounters and turn them into opportunities. An example of this reframing comes from another participant, Kiri, who was taking time away from working (in a male-dominated workplace) to go on maternity leave. Although concerned about the implications of being away from her team and feeling different to her male colleagues, Kiri chose to celebrate her difference: ‘…I was about to have a baby, so I let everyone know’ (see Table 5 Participant Quotation a).

Table 5. Spectrum of strategies – From threats to opportunities

Kiri may have been anxious about her impending absence from her workplace; however, Kiri employed a strategy to redirect her colleague's attention elsewhere through a win-win solution – the training of her replacement. Tempered radicals make use of a variety of tools to turn a threat into an opportunity, including interrupting to change momentum, sharing an issue with others to make it more transparent, diverting an encounter, delaying, and using humour to release pressure. While celebrating the news of her maternity leave, Kiri uses this approach to redirect attention to the challenges of her absence. Difference is presented in a positive way.

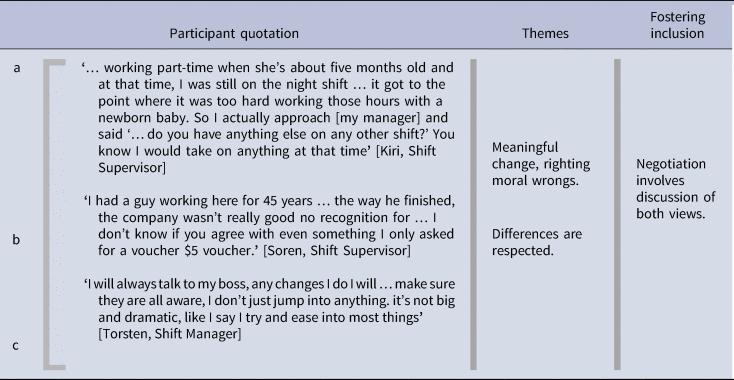

Mid-range in Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001b) spectrum of strategies, the tempered radical draws on their negotiation skills to manage challenging situations. Continuing Kiri's story, when Kiri came back to work as the only new mother in the combined production teams, she found herself having to negotiate for more flexible shift arrangements: ‘…it was too hard-working those hours with a newborn baby’ (see Table 6 Participant Quotation a).

Table 6. Spectrum of strategies – negotiating a change

Kiri's negotiations show the tempered radical's ability to heighten the awareness of the challenges they face, in this case by a new parent attempting to return to work. Kiri inspires change by providing a nudge for her organisation to reconsider working arrangements for new parents. As Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001b) notes, tempered radicals teach valuable lessons and inspire creative change. Another participant, Phillipe, a production operator, shares a similar story of tempered negotiation. Phillipe's work was key to his family's wellbeing, and while he respects the need for work output, he quietly influenced how the organisation considers the availability of production workers to complete overtime during the weekend: ‘I can't do it all the time … I had to pull out some of them ‘cos of my kids’ sports … that's what I didn't have when I was growing up’. By negotiating out of weekend overtime, he makes a gradual change in improving work-life balance. No easy feat, as Meyerson and Scully (Reference Meyerson and Scully1995) notes that the pressure is usually towards assimilating to work requirements and surrendering the outside or home identity. As Phillipe and Kiri's narratives illustrate, the tempered radicals within this study are calling on their broader life experiences to draw different worlds closer together, in the best interests of others and their organisations, and they do so without necessarily seeking compromise. Briscoe and Gupta (Reference Briscoe and Gupta2016) note, tempered radicals are motivated to do this because they hope for a mutually beneficial outcome for themselves and their organisations.

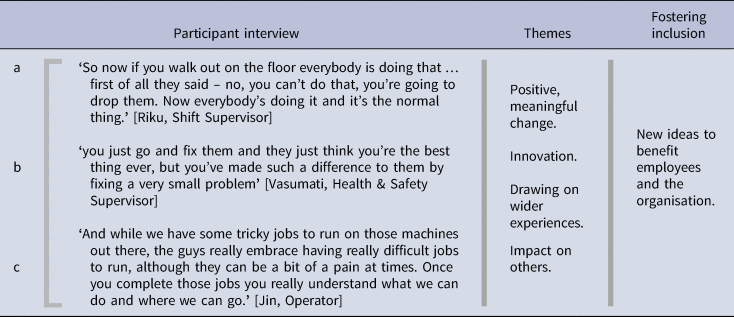

Implementing evolutionary change resonates with the tempered radical, preferring a considered, subtle approach when influencing organisational routines in their workplace. Achieving small wins over time is a powerful change mechanism and can be bundled together to promote more comprehensive learning and change. Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001a) notes, if you add up enough small changes and inspire enough people, then sooner or later, you will see significant change. This is demonstrated in our current study through Riku, a shift supervisor in a large urban manufacturing organisation. During the earlier part of his career, Riku used his background as a mechanic to help reduce the number of strenuous brute-strength actions production operators had to complete to load a machine (see Table 7 Participant Quotation a). This was particularly important as the demographics of the staff were changing, with, for example, and increasing number of women joining the operational teams.

Table 7. Spectrum of strategies – leveraging small wins

He did this by patiently demonstrating over time new methods to his peers: ‘… first of all they said – no, you can't do that, you're going to drop them’. Manufacturing has historically relied on repetitive processes to produce goods, and process changes are usually driven by top management and delivered down to the production floor (Matsuo, Reference Matsuo2019). Nevertheless, with Riku's narrative, we see a lower-level employee slowly and surely transforming a heavily controlled environment, resulting in benefit for all production employees and the organisation: ‘Now everybody's doing it’. The change is achieved quietly but effectively, as Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008) notes, it is essential not to confuse the speed and visibility of change strategies with their impact. Badaracco (Reference Badaracco2001: 121) concurs, suggesting of quiet leaders, ‘their modesty and restraint are in large measure responsible for their extraordinary achievements’. Even when issues are close to the heart, participants demonstrate their ambivalence and patience.

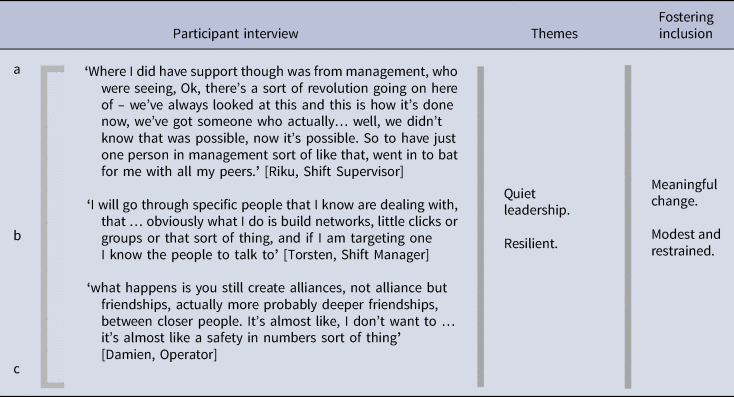

Towards the more visible and collaborative options on Meyerson's spectrum of change strategies, the tempered radical chooses to bring in allies and friends to support the desired change. Allies and friends grant access to resources and powerful partners, expertise and support, and gives issues more prominence and attention. Riku's success with changing established work processes did not come easily, and Riku notes the backlash he received from his peers when attempting to change the accepted process: ‘that was a tough journey because a lot of people saw that as not following the right process’. However, he explains how he gained support from a supervisor to help support his ‘radical’ ideas for change: ‘one person in management sort of like that, went in to bat for me’ (see Table 8 Participant Quotation a).

Table 8. Spectrum of strategies – strategic alliance building

Meyerson and Scully (Reference Meyerson and Scully1995) explain that tempered radicals often work alone, but if needed, strategic alliances can be formed as they help gain a sense of legitimacy. Tempered radicals working in an operational position, in particular, need both resources and support to achieve the social change they desire (Bajaba et al., Reference Bajaba, Fuller, Simmering, Haynie, Ring and Bajaba2022). By forming coalitions, the tempered radical gains the power to bring attention to issues more quickly than they could have by working alone. Torsten (see Table 8 Participant Quotation b), continues his narrative: ‘as long as you can get that little bit of buy in … there is your foothold’, and then ‘through time, they realise… this does make sense, now we can see why there are the benefits’. The tempered radical, while not necessarily aspiring to hold a leadership position, foster's inclusion as a quiet leader using modesty and restraint and can do so at any level of the organisation.

Discussion

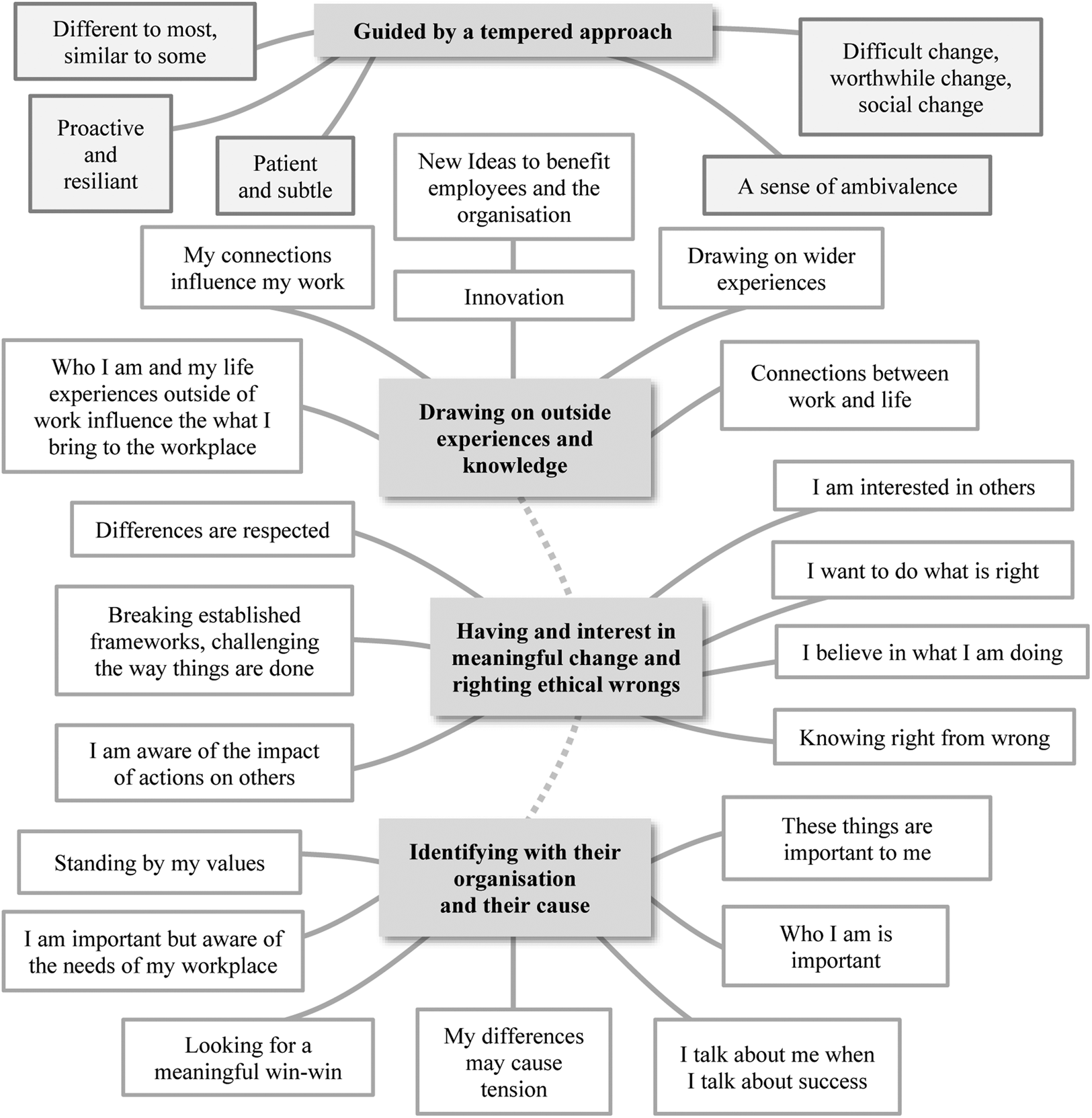

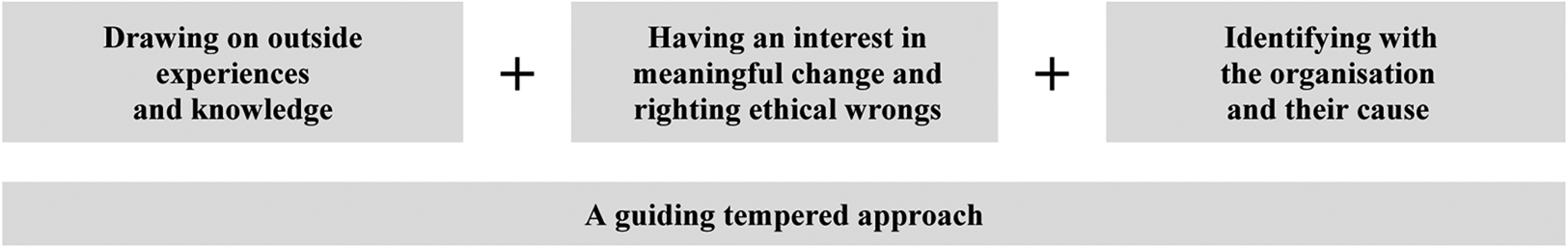

The findings, considered with the guidance of Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2008) frameworks, were formed through a middle-ground approach incorporating the participant interviews, the researcher's analysis and theoretical frameworks. Figure 2 below is a thematic map developed from the findings of this study that depicts the important themes.

Figure 2. Thematic map of findings.

Shaped by participant attributes, the data confirms the subtle signs that indicate tempered radicals, supporting the credibility and strength of participant selection. Our findings derive three main characteristics that guide the tempered radical towards fostering inclusion in the workplace: implementing changes guided by life experiences and personal interests, a desire for subtle yet meaningful change, and balanced respect for their workplaces, all via a tempered approach. The prominent themes form an inclusion framework that illustrates the critical characteristics of tempered radicals who incorporate inclusion in the workplace (see Figure 3), building on current theory and the constructs examined in the literature.

Figure 3. Tempered radical's inclusion framework.

Drawing on outside experiences and knowledge

The first element of the inclusion framework captures how life experiences and knowledge gained outside the workplace influences the tempered radical's decisions over operational activities in the workplace. The tempered radical not only draws on knowledge from within the workplace; they draw from their own experiences, values and identities formed beyond the organisation. The tempered radical brings their ‘self’ into the picture, calling on their values and identity to proactively guide their desired social change (Bajaba et al., Reference Bajaba, Fuller, Simmering, Haynie, Ring and Bajaba2022; Yolles & Di Fatta, Reference Yolles and Di Fatta2017). Throughout the findings of this current study, we see the participants recognising and reacting to their difference; Phillipe realises that he ‘… had the wrong crowd around me’, and Heather ‘… this is a male-dominated industry’. As Kelman (Reference Kelman2006) explains, a typical reaction might easily involve compliance or accepting influence from another person or group in return for a favour. However, both Phillipe and Heather choose not to comply; drawing on their experiences, they make a judgement and purposefully look to change the norms. Their personal lives and business world are not separated, and personal identity influences their approach (Solomon, Reference Solomon, Shaw, Barry and Sansbury2009). While being aware of the need for compliance, and the potential contribution to society by their organisations, the tempered radical foster inclusion through their strong orientation towards values and drawing on their personal interests and life experiences.

Having an interest in meaningful change and righting ethical wrongs

The second element of the tempered radical's inclusion framework is the desire to create mutually beneficial and meaningful change. As noted in literature, Bailey and Madden (Reference Bailey and Madden2017) propose that meaningfulness at work arises when an individual perceives a connection between work and a broader transcendent life purpose beyond the self. Based on our findings, meaningful change, for the tempered radical, is a combination of providing benefit for society within the alignment of their own interests while at the same time recognising the commitment to their organisation. This is what makes tempered radicals valuable agents of organisational transformation (Scully & Meyerson, Reference Scully and Meyerson1993), working proactively towards organisational transformation that benefits society, such as inclusion. Bajaba et al., (Reference Bajaba, Fuller, Simmering, Haynie, Ring and Bajaba2022) recommends tapping into the tempered radical's proactive personality and seeking out those who are well suited as minority members to generate a more robust diversity climate.

When considering Hackman and Oldham (Reference Hackman and Oldham1976) job characteristic theory, participants show, for the tempered radical, task significance is synonymous with the degree to which the job has an impact on the lives of others. As Vasumati comments following making a change to a longstanding process: ‘… they just think you're the best thing ever … you have made such a difference’. A positive spin-off, the tempered radical's interest in transformation for the benefit of society and their value of the impact of any transformation could, as Hackman and Lawler (Reference Hackman and Lawler1971) suggest, have a positive impact on work performance.

Identifying with both the organisation and their values

One of the strengths indicated in literature regarding the tempered radical is their respect for differing viewpoints (as opposed to compromising). This strength is a powerful tool to foster inclusion – where a difference of views, or values, or identity is embraced and respected, not compromised. This ambivalence is the third element of the tempered radical's inclusion framework. The tempered radical recognise organisational goals, for example, of profit and expansion, while maintaining an interest in the wellbeing of others. The strategies of the tempered radical enable ‘successfully navigating a middle ground … choosing their battles, creating pockets of learning, and making way for small wins’ (Meyerson, Reference Meyerson2008: 6). We see this in this current study through Lewis, who guides his colleagues to be ‘the lowest-cost producer of the best whole milk powder’ so that they will ‘be able to survive, keep our jobs’. Weick (Reference Weick2004) explains that ambivalent individuals have an attitude of wisdom, which is recognising wisdom is not just holding on to knowledge, which can be fallible, but putting knowledge to use.

Adopting a tempered approach

The tempered radical's inclusion framework's three characteristics are underpinned by an essential attribute of the tempered radical – the ability to work patiently and subtly to achieve change. As Meyerson (Reference Meyerson2001a) suggests, organisations initiate change through either drastic action or evolutionary change. Drastic action, driven from the top-down as a result of factors such as competition, resource availability, technology, regulation or political landscape, can be implemented quickly, but the approach usually brings significant disruption and pain. In contrast, the evolutionary change supported by the participants of this study is far more subtle, incremental and brings about change that is less disruptive and often more sustainable.

Practical implications

How tempered radicals foster inclusion in the workplace is central to this study and particular care was taken to include participants across the hierarchy of positions within manufacturing industries. This study reveals that although the tempered radical may go unnoticed, or indeed be invisible, even at lower levels of organisations they can use their proactive nature and personal interests towards their cause to influence inclusion within organisations. The implication for practitioners is that tempered radicals are an untapped source that could help foster the advantages of diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Through life experience, they are acutely aware of difference. Without compromise they seek to increase awareness of this difference with a resilience that is not swayed by their equal enthusiasm for the organisation's success. The strong link between the personal interest of the tempered radical and their desire to positively impact social change gives tremendous energy to these hidden champions of inclusion.

Limitations and future research

The primary limitation of this study is the sample selection; a broader sample would add further robustness to the findings. There is a gender imbalance in the data, with more than twice as many males than female participants. Moving in parallel with ‘the goal to bring change to the condition of women in some way with the help of research’ (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Reference Eriksson and Kovalainen2016: 331), analysing findings from a gender point of view might highlight asymmetry in power relations (a key consideration in manufacturing) and interviewing sufficient female participants may reveal differences between women as a group. To build a stronger evidence base for a study centred on inclusion, any future research should continue to include a balance of organisation positions levels, including lower-level operational positions.

The primary researcher is a senior member of the manufacturing industry. There is a potential for bias through the power relationship of the researcher and participant, particularly considering the manufacturing industry's hierarchical nature and the junior level of some of the participants. To mitigate the influence from this potential bias, the primary researcher took a reflexive approach, reflecting on their role and their relationship with the participants and the research process, moving back and forth during the different stages various stages of this research.

Organisations would do well to draw on the abilities of all their tempered radicals to foster inclusion, and for such benefits to be fully realised, further research is needed to consider the influence of the organisation on the tempered radical's ability to foster inclusion. This would provide a greater understanding of any potential challenges tempered radicals might face relative to each hierarchical level.

Conclusion

In a world of workforce mobility and globalisation, having a greater understanding of fostering inclusion will help organisations manage employees coming from increasingly demographically diverse groups (Harrison, Boekhorst, & Yu, Reference Harrison, Boekhorst and Yu2018). Additionally, with workplaces more intertwined with interpersonal relationships and social interaction, organisations must extend the scope of inclusion and consider diversity beyond recognisable surface-level attributes to encompass individual differences such as upbringing, lifestyles, family status, disability, education or physical attributes (Härtel, Härtel, & Trumble, Reference Härtel, Härtel and Trumble2013; Hope Pelled, Ledford, & Albers Mohrman, Reference Hope Pelled, Ledford and Albers Mohrman1999; Rupert et al., Reference Rupert, Blomme, Dragt and Jehn2016). Where prior studies of tempered radicals have examined their attributes, strategies, and ability as change agents, none to the knowledge of the authors have directly considered how tempered radicals might influence inclusion within the workplace. Additionally, prior studies include participants predominantly from senior to mid-level positions in financial services or computer industries. This current study includes tempered radicals working in operational and front-line supervisory positions within the richly diverse and rapidly changing environment of manufacturing industries.

A contribution to knowledge is made through the development of the tempered radical's inclusion framework, depicting the characteristics called on by the tempered radicals to foster inclusion in their workplace. This inclusion is fostered through a combination of drawing on their life experiences, being ambivalent to their identity and their organisation's goals, and having a desire to make the world a better place. Understanding the experience of being different, driven through by their proactive nature, the tempered radical foster inclusion with subtlety and resilience; they are the invisible champions of inclusion.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Peter McGhee is a guest editor on the Special Issue of the Journal of Business Ethics: Ethics and the Future of Meaningful Work.

Chris Griffiths I have over 25 years' experience in managerial roles in various organisations across the manufacturing and service sectors. I have an MBA and am currently a PhD candidate at the Auckland University of Technology. Through my PhD I have presented a paper at the 2019 European Academy of Management Conference, and independently of my PhD I have co-authored a paper published with the Journal of Management and Organisation. My research interests are diversity and inclusion within organisations.

Edwina Pio Recipient of a Royal Society medal, and Duke of Edinburgh Fellowship, Fulbright alumna, is New Zealand's first Professor of Diversity, University Director of Diversity, Member of a Ministerial Advisory group and elected Councillor on the governing body of the Auckland University of Technology. A prolific writer, her research is published in leading international journals and media outlets.

Peter McGhee I am a senior lecturer in the Department of Management in the Faculty of Business, Economics and Law at Auckland University of Technology where I have been teaching in the area of business ethics and sustainability for over 20 years. I have been previously a member of AUTEC, the university research ethics committee. My expertise and research interests are in business ethics, workplace spirituality, and sustainability. I am a current board member of The Leprosy Mission New Zealand (TLMNZ), a development agency working with people affected by leprosy in the majority world. I have been on this board for 6 years. I currently supervise postgraduate students in Workplace Spirituality, Business Ethics, Sustainability & Leadership.