Obituaries customarily call for writers to steer clear of negative remarks, particularly when the deceased is a professional associate or colleague. If good conscience dictates against a positive obituary, why write an obituary at all? Journalistic duties likely came into play when, as the music critic for the newspaper Le Voltaire, in October 1880 Saint-Saëns provided an appreciation of Jacques Offenbach, recently deceased, that is as parsimonious in its praise as harsh in its critique. Not content with the ephemeral impact of an article for the daily press, Saint-Saëns anthologized it five years later in Harmonie et mélodie, a collection destined to become a high-profile witness to his aesthetic colours.Footnote 1 The tone bespeaks Saint-Saëns's often-noted prickly character. Admitting that Offenbach occasionally had good melodic and harmonic ideas, a sharp wit, and sound theatrical instincts, he drove the bulk of his ‘tribute’ to the final sucker punch: having launched the review with faint praise (‘It is not a great musician who has just passed away, but a big musical personality’), he ended it with ,‘But he wasted it all’.Footnote 2 At the heart of Saint-Saëns's disapproval lay his opinion that Offenbach was poorly trained as a composer, lacked craft, and slapped scores together at high volume with correspondingly low quality. His prosody desecrated the French language.

In 1880, Saint-Saëns equated such artlessness with the entire genre of opérette (or opéra bouffe as it was also called, though not by Saint-Saëns), whose invention he erroneously attributed solely to Offenbach. He vented his fury that a genre saddled with such mediocre music had become so popular (we may want to recall here that popularity in the theatre had so far evaded Saint-Saëns himself). It had even elbowed aside historically entrenched opéra comique, which generally appealed to much higher musical values and could be characterized as ‘shabby’ (‘mesquin’) only at its absolute worst. In opérette, ‘shabby’ represented the high end of the quality scale, which extended downwards from there to … nul. Having given itself ‘the goal of making everything ugly and small’, opérette had contaminated the musical taste of the entire music-loving public. Saint-Saëns never changed his opinion and, forever perplexed that Offenbach's music did not simply fade into oblivion, continued to attack it even late in life. (But he did soften on opérette itself as by this time his friends Charles Lecocq and André Messager had proven themselves to be musically respected, and respectful, purveyors of the genre.) ‘Will Jacques Offenbach ever become a “classic”’ he asked in 1911. ‘It would be unexpected [ … ] But anything is possible, even the impossible’.Footnote 3 Saint-Saëns's rejection of Offenbach smacks of the brandishing of elite musical taste against populist accessibility. The costs of slumming were simply too high. Composition was serious business and there were classical values to be upheld that could stand the test of time.

Although few settings of ancient classical culture populate the nearly 100 opérettes that Offenbach wrote, two of these – Orphée aux enfers (1858) and La belle Hélène (1864) – quickly assumed iconic status in his oeuvre.Footnote 4 Orphée was the first full-length opérette produced by Offenbach's company at his own Bouffes-Parisiens after a series of 22 one-act pieces and has since been regarded by many from his day to ours (perhaps questionably) as the founding work of the genre. It remained a perennial favourite, so much so that Offenbach expanded it in 1874. La belle Hélène, developed around the story of Helen of Troy, was Offenbach's first premiere at the Théâtre des Variétés and because of this marked an important step in moving beyond the confines of his own house to conquer other French stages. Saint-Saëns mentioned both works in his obituary and then five years later subjected the latter to particularly withering criticism for lamentable text setting, another essay that made it into Harmonie et mélodie. Mention might also be made of Daphnis et Chloé (1860), and beyond Offenbach to other composers active in opérette – figures such as Hervé, Léo Delibes, and Frédéric Barbier – who also turned to ancient subjects frequently enough for the historian Jean-Claude Yon to propose opérette antique as a subgenre.Footnote 5 Infused with the spirit of desublimation, ridicule, and irreverence, such works made a point of playing up anachronism: characters from antiquity who communicated in modern argot and participated in polkas and quadrilles. Figures consecrated by centuries of reverential artistic and literary representation provided a vehicle for thinly veiled satires of modern life that left no place for genuine investment of the listener in their emotional world. Ultimately Yon concludes that, more than a subgenre, opérette antique represented the quintessence of opérette writ large. Such is also the implication of Émile Zola's famous description of a performance of Blonde Vénus at the beginning of his novel Nana (1880), an imaginary opérette that he uses as a synecdoche for the genre and, on a larger level within the symbology of the novel, for Second Empire decadence in general: ‘This carnival of the gods, Olympus dragged in the mud, a whole religion, a whole poetic tradition outrageously mocked’.Footnote 6

Saint-Saëns ventured into Hellenic territory as a creative artist in 1893, eight years after the publication of Harmonie et mélodie, with a two-act comedy to a libretto by Lucien Augé de Lassus about a famous ancient courtesan eponymously called Phryné. It was his first comic stage piece after an early one-act comic japonnerie called La princesse jaune premiered in 1872.Footnote 7 The turn to light-heartedness after 20 years by a composer with a sternly serious public persona surprised some critics (nota bene: Saint-Saëns forbade publication and public performances of the hilarious Carnaval des animaux written a few years before, with its tortoise movement where the can-can from Orphée aux enfers unfolds in slow motion in low strings beneath ethereal piano chords). That Saint-Saëns pointedly styled Phryné an opéra comique belongs to the account of his engagement with opérette reviewed here not only because of the ancient subject matter redolent of Offenbach's most famous hits, but also because opéra comique was the other side of the coin to the slapdash frivolity that Saint-Saëns condemned. In the climate of heightened nationalistic discourse he consistently championed the genre as quintessentially French – ‘éminemment national’ as the characterization went in the critical press – and, in particular, argued for the aesthetic viability of spoken dialogue in music theatre, especially in the essay ‘La défense de l'Opéra-Comique’, a stirring plaidoirie written in 1898 and reprinted often. Here he beat back the critiques of Wagnerian zealots by nostalgically recalling the great repertoire of earlier in the century, works by Auber and Adam that had become ‘classic’ and were also progenitors of Massenet's more recent Manon and Bizet's Carmen. All were composers of skill and merit. He was too, of course, and Phryné offered an opportunity to make the case for the continued viability of opéra comique on the stage instead of in a critical essay, that is, to mark out aesthetic space for modern musical comedy that was not Offenbach's, yet on the same ground of classical antiquity. As I will suggest here, that space allowed a conjoining of classical subject matter not only with a classical canon of painting and sculpture but also with musical qualities deemed classical in the fin-de-siècle environment.

***

To my ear there is little in Saint-Saëns's delightful music that one might confuse for Offenbach's style. That is, except for one passage in the Act I Finale (Ex. 1a). Dicéphile (baritone), the elderly guardian of public morality who is ridiculed for hypocrisy, comes in for massive deflation when Nicias (tenor), Phryne's (soprano) impoverished lover, arranges for a goatskin water bottle to be placed awkwardly on Dicéphile's bust in a public square. The quick turnaround of rhymes (‘On raconte / Qu'un archonte / Était un coquin maudit / Son mérite / Hypocrite / Un beau jour se démentit’), mechanistic repetition of four-square musical phrases by the chorus, staccato choral underpinning (not shown), and skipping rhythms all give the passage an undeniably Offenbachian quality. Indeed, there are enough elements in common with the ‘Anathème’ chorus in the first act finale of Orphée aux enfers (in its 1874 revision) to suggest that Saint-Saëns may have had it in mind: similar rhythm, melodic motif, and phrase structure (Ex. 1b). Here Saint-Saëns would certainly not have approved of Offenbach's dubious prosody. The chorus repeats ‘Anathème sur celui qui sans pitié’ numerous times before the phrase is completed so that it makes sense ‘Anathème sur celui qui sans pitié / Réfuse une larme même à son moitié’.

Ex. 1(a) Camille Saint-Saëns, Phryné, Act I Finale

Ex. 1(b) Jacques Offenbach, Orphée aux enfers, Act I Finale

Despite his criticisms of Offenbach, when it came to writing a comedy, did Saint-Saëns assimilate his idiom at this moment in the Act I finale to increase the levity of his work? Or should the passage at the end of Act I be understood within quotation marks as a parody of Offenbach – parody in the sense of imitation within a frame of critical distance from the target?Footnote 8 The critic Ferdinand Le Borne wrote of a ‘vulgarité voulue’ (intended vulgarity) in the passage, and it is with this position that I agree.Footnote 9 My premise is that Saint-Saëns referred to Offenbach here only to distance himself from him, that is, to underline how different (better?) his approach to comedy really was. Or, if this was not exactly at the forefront of his intent, it provides us today with a useful critical hook to understand the classicistic foil to Offenbach that Saint-Saëns created.

Saint-Saëns's biographer Jean Bonnerot wrote of how Phryné lived up to its generic designation in score and libretto as an opéra comique.Footnote 10 Early critics generally did so as well, but this perspective was far from unanimous. Alfred Bruneau confessed to be taken aback at first, thinking that Saint-Saëns had written an opérette, before he breathed a sigh of relief: ‘How my fears were allayed. Because Phryné really is an opéra comique, a classical opéra comique’.Footnote 11 Charles Martel in La Justice asserted: ‘Saint-Saëns really did treat this little story as an opéra comique […] One cannot laugh in a more classy way’.Footnote 12 To Léon Kerst of the wide-circulation Le petit Parisien, the work was ‘un pur opéra comique’.Footnote 13 Ernest Reyer reported in the Journal des débats that some heard Phryné as an opérette.Footnote 14 They were wrong, he said. Saint-Saëns's score was in the vein of Auber, ‘insignificant music composed by a great musician’ (‘de la petite musique faite par un grand musicien’). The pseudonymous Frimousse in Le Gaulois may have been one of Reyer's targets, as he called it ‘an opérette, yes you are reading correctly, and what is more a Greek opérette, like La belle Hélène’.Footnote 15 Many years later, in a review of a Phryné revival in 1910, the respected critic Adolphe Jullien – musically well informed and writing with historical distance – unequivocally categorized it as an opérette.Footnote 16

In arguing for Phryné as an opéra comique, my position is that of the imputed intention of the composer seen within the frame of his attitude towards Offenbach's opérettes antiques combined with a more presentist orientation that seeks out the most critically useful perspective. But in this conundrum about genre, we need to recognize new research that documents enormous slippage between the two terms at the fin de siècle, with opéra comique sometimes applied to light works produced at low-brow theatres and sung by half-trained musicians, and opérettes sometimes mounted at prestigious venues (like the house actually called the Opéra Comique) and sung by extraordinary artists.Footnote 17 Saint-Saëns's bon mot that opérette was ‘the daughter of opéra comique who turned out badly’ says a lot, inasmuch as it posits a genetic relationship, and hence similarity, between the two.Footnote 18 With opéra comique and opérette, no enumeration of characteristics will allow consistent identification of one instead of the other in an ontological vacuum. Generic purity at the fin de siècle is a rara avis. Positing an ideal type of each is limited as a critical approach. Of course, one can speak of misinformed attempts to identify genre, or unpersuasive ones, or others driven by bad faith – but they all need to be evaluated fairly against the different contexts in which they are made (temporal, geographic, or social) as well as the critical, economic and performative purposes for their articulation. For some listeners, Phryné may not sound like an opérette when placed beside Offenbach but may resemble one when placed beside Die Walküre. As it happens, Wagner's opera received its Paris premiere shortly before Phryné was unveiled and reference to it slipped into many reviews of Saint-Saëns's piece not only because of chronological proximity but also because of Saint-Saëns's developing reputation as inimical to Wagner's influence on French culture. Other writers will note that the premiere of Phryné at the house called the Opéra Comique strongly marks its attribution to the eponymous genre. Still others will remember that during the period of composition Saint-Saëns intended the work for an ephemeral company called the Théâtre de la Renaissance, run by his friend and former collaborator Léonce Détroyat, a house that seemed open to accept works in a wide range of comic registers. Someone else might attribute to the opérette side of the ledger a parallel between a marked erotic element at the end of Phryné – more about this anon – to the loose sexual mores of Offenbach's ancients. In continuing to explore the opéra comique side of Phryné this essay is a small chapter in the kaleidoscopic operation of French comic genres in the period.

***

Saint-Saëns came to Phryné from a lifelong interest in antiquity. He not only drew inspiration from classical material in compositions such as the symphonic poems Le rouet d'omphale and Phaeton, but also approached antiquity as a scholar, for example by writing a short essay in 1886 on stage decor in Roman theatre.Footnote 19 There he developed an argument, largely based on published iconography and since then largely discredited, that Pompeiian murals depicting unusually proportioned architecture offered clues to the mise-en-scène of ancient theatre.Footnote 20 Just a few years later, shortly after he finished composing Phryné in 1892, Saint-Saëns addressed his colleagues at the Institut de France on ancient lyres and kitharas, a text that soon became widely available in the musical weekly Le monde artiste. He kept returning to these instruments in several additional publications later in life, each time refining his findings based on new iconographical evidence. This research claimed enough authority for one version of it to appear in the authoritative Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du Conservatoire (1913), the most significant French music encyclopedia of its time.Footnote 21

The years 1892 and 1893 were particularly rich for Saint-Saëns's engagement with ancient classical culture. In June 1893, less than a year after the address to the Institut about ancient instruments, he accepted a commission to supply incidental music for a revival of Sophocles's Antigone at the Comédie Française in November, soon to be taken up at the summer Théatre d'Orange in the Midi. This was no ordinary incidental music. Saint-Saëns referred to it as archéologie and produced a score with monophonic and two-part modal part writing and a reduced instrumental accompaniment that attempted to reproduce an imagined Greek melos. He claimed to have studied François-Auguste Gevaert's massive Histoire et théorie de la musique de l'antiquité (1875–81) to achieve an authentic result. Nevertheless, given the parameters within which he worked – including a rhyming verse translation that looks more like a nineteenth-century opera libretto than like Sophocles – the result made for a dubious kind of authenticity, although the experimental nature of the score cannot be denied.Footnote 22 This activity fed the reputation of Saint-Saëns as a highly serious composer – ‘perhaps our most severe master’ (maître, peut-être le plus sévère) wrote Charles Darcours in his Phryné review for Le Figaro Footnote 23 – for whom comedy was not normal business. Recall that Saint-Saëns's own critique of Offenbach was animated by a sense of general cultural superiority. Critics were surprised that he took on a comedy: he would hardly have been expected to produce something trivial or silly.

Add to this that librettist Lucien Augé de Lassus, a minor writer of plays and librettos, was himself no slouch on matters ancient.Footnote 24 An erudite classicist, he wrote several books for general readers that brought specialized findings of recent archaeological work in Greece to a wider public. As he tells it in his biography of Saint-Saëns,Footnote 25 a theatrical project around Phryne had been his longstanding interest well before he approached the composer. He was manifestly familiar with the source of the courtesan's story, the thirteenth book of The Deipnosophists by Athenaeus of Naucratis:

-

[1]Now Phryne was a native of Thespiae; and being prosecuted by Euthias on a capital charge, she was acquitted: on which account Euthias was so indignant that he never instituted any prosecution afterwards, as Hermippus tells us. But Hypereides, when pleading Phryne's cause, as he did not succeed at all, but it was plain that the judges were about to condemn her, brought her forth into the middle of the court, and, tearing open her tunic and displaying her naked bosom, employed all the end of his speech, with the highest oratorical art, to excite the pity of her judges by the sight of her beauty, and inspired the judges with a superstitious fear, so that they were so moved by pity as not to be able to stand the idea of condemning to death ‘a prophetess and Priestess of Aphrodite’. And when she was acquitted, a decree was drawn up in the following form: ‘That hereafter no orator should endeavour to excite pity on behalf of anyone, and that no man or woman, when impeached, shall have his or her case decided on while present.’

-

[2]But Phryne was a really beautiful woman, even in those parts of her person which were not generally seen: on which account it was not easy to see her naked; for she used to wear a tunic which covered her whole person, and she never used the public baths. But on the solemn assembly of the Eleusinian festival, and on the feast of the Poseidonia, then she laid aside her garments in the sight of all the assembled Greeks, and having undone her hair, she went to bathe in the sea; and it was from her that Apelles took his picture of Aphrodite Anadyomene; [591] and Praxiteles the sculptor, who was a lover of hers, modelled the Aphrodite of Knidos from her body; and on the pedestal of his statue of Eros, which is placed below the stage in the theatre, he wrote the following inscription:-

Turning first to the second paragraph of the excerpt: it supplies two essential elements of the backstory for our purposes. First, Phryne never made public display of her body, except on the feast of Poseidonia when she laid aside her garments in front of all, undid her hair, and bathed in the sea. The ancient Greek painter Apelles of Kos captured the image as Aphrodite Anadyomene, a work no longer extant. Second, Athenaeus informs us that the sculptor Praxiteles was one of her lovers and also immortalized her, as Aphrodite of Knidos. This was the first full (and long lost) representation of a female nude, familiar from later Roman and Renaissance renditions that adopted the pudica convention of concealing either her genitals, a breast, or both, as with the Capitoline Venus (=Aphrodite) or the Venus de’ Medici.Footnote 27

In the first paragraph, Athenaeus recounts how the prosecution of Euthias failed previously. Phryne was once again hauled before judges for some unspecified transgression and defended by the lawyer Hypereides. Seeing that he was not getting anywhere with the judges, he ripped open her tunic to show her naked bosom. Moved by pity and superstitious fear in the presence of a courtesan suddenly imagined as a ‘priestess of Aphrodite’, the tribunal acquitted her. This episode inspired a painting Phryné devant l'aréopage by Jean-Léon Gérôme (exhibited in 1861, Fig. 1) that became famous through derivative products sold by his canny dealer (and father-in-law) Adolphe Goupil, including high-quality engravings and statuettes of Phryne.Footnote 28 The Gérôme painting was well known enough for several reviewers of the premiere to refer to it. Augé de Lassus was aware of it as well. We can savour the theatricality of Gérôme's approach: the confident glare and flamboyant gesture of Hypereides, Phryne's instinctive hiding of her face, and the almost exaggerated expressions of terror from the men. This is not to mention the sensationalistic modulation from Atheneaus's report of an exposed bosom to Hypereides's unveiling of a completely nude figure in a crowded room of men. The painting caused controversy because it depicted Phryne, the public courtesan, in an attitude of shame. And so much does she resemble the marble likenesses of the goddess that the judges, for their part, are seized with fear at being in the presence of Aphrodite. For Degas, it was almost pornographic because it made her seem needlessly passive. Zola thought it salacious. Théophile Gautier noted disapprovingly that she is represented as a ‘young girl, thin, petite, delicate, and too virginal for the subject’ but found much to praise in the liminality of a beautiful body ‘turned and polished like an ivory statue, [that] bursts forth in all of its whiteness and eloquently pleads her case’.Footnote 29 Both the sensationalistic aspect of the painting as well as the more considered reflections on the ambiguity between statue and human flesh that it provoked left their mark on the final scene of Saint-Saëns's opéra comique.

Fig. 1 Jean-Léon Gérôme, Phryné devant l'aréopage, 1861, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg

From these ancient and modern sources the way to the libretto was marked by an intermediate stage. In his biography of the composer, Augé de Lassus wrote of reading a short play based on the Phryne story to Saint-Saëns long before the opéra comique project saw the light of day.Footnote 30 It seems likely that what he presented to the composer at that time is equivalent to Phryné, comédie en un acte, a play he had printed in 1879, seemingly at his own expense.Footnote 31 Though it was never performed, it would form the kernel of the libretto.

For critical purposes relating to the opérette–opéra comique dialectic, Augé de Lassus's description of this early initiative is telling. He intended it as a kind of carte de visite to prestigious theatres like the Comédie Française and Odéon and in a style along the lines of François Ponsard and Émile Augier, two writers who brought the ancients back to romantic letters after their banishment for two decades. Two of the best-known products of this orientation are works by Gounod: the opera Sapho (1851) to a libretto by Augier and the incidental music to Ponsard's play Ulysse (1852). The point here is that Augé de Lassus positioned himself in a high artistic lineage, which he substantiated with multiple arcane references to classical Hellenism and, in style, by writing the play entirely in Alexandrines, as in the French classical theatre. The play emerges from the Gérôme painting to the extent that Dicéphile says explicitly that he represents the entire aréopage, the site of law courts in Athens, whereas Athenaeus does not mention the location. Dicéphile, as the only other character in the play besides Phryne herself, takes up the case against the courtesan for immoral behaviour. He is a self-congratulatory paragon of virtue, but it turns out that he has hugely repressed feelings towards her. Sensing this, she sets about to seduce him, asking for his assistance with various items of her toilette. He weakens in his resolve. This would become the narrative premise of the second act of the libretto. The set anticipates the opéra comique as well, with a statue of the Venus de’ Medici, jewellery and – on the risqué side for a stage prop at this time – a lit de repos (day bed). Because, as Athenaeus notes, Phryne had modelled for the original version of the Venus statue, this derivative nude marble representation is manifestly meant to trigger the erotic imagination of Dicéphile (and perhaps of the theatre viewer as well). The more prurient side of the Gérôme painting lurks here. At the end, Phryne promises him more, but on condition that he sign her acquittal. The play ends unresolved.

A dozen years after publication of the play, sometime in the middle of 1891, Saint-Saëns agreed to collaborate with Augé de Lassus, promising the project to Léonce Detroyat's new Théâtre de la Renaissance, as previously noted. In the meantime, Henri Meilhac, Offenbach's frequent collaborator including on La belle Hélène, had tried his own hand with a play Phryné premiered at the Théâtre du Gymnase on 14 February 1881. Space does not allow for an account of this production, but within the frame of our critical question it too plays off the Gérôme painting. Phryne is brought to court for various sacrilegious pronouncements and Euthias uses the occasion to acquit himself of a debt of 200,000 drachmas that he has incurred with her. Phryne decides to defend herself, and at the height of her argument belittles Euthias by yanking his cloak away! Auguste Vitu, the critic for Le Figaro, reported on the ridiculous inversion: “Seeing Euthias almost naked with his skinny arms and knock-kneed, the aréopage was seized with indignation at so much ugliness. With one voice it absolved Phryne and commanded Euthias to pay the 200,000 drachmas’.Footnote 32 Add dance-like music and this is the stuff of opérette.

Augé de Lassus aimed for a high literary tone in the opéra comique by writing rhyming verse throughout, where the generic norm was for prose spoken dialogue. This tilted the generic scales away from opérette, with its everyday spoken argot. The opéra comique was longer than the one-act play of 1879 and accommodated more characters along with passages for chorus. The story acquired all its bulk before the final scene of Phryne's seduction of Dicéphile. The first act opens with Dicéphile looking forward to the ceremonial unveiling of a monument to himself in a public square, an ironically bodiless representation in the form of a bust. He also arranges for creditors to seize the belongings of his deeply indebted nephew – and Phryne's lover – Nicias. Phryne orders her slaves to protect Nicias, who at the end of the first act leads her and other Athenians in desecrating Dicéphile's bust with the goatskin water bottle. At the beginning of the second act Nicias and Phryne sing of their love, and she tells of being mistaken for Aphrodite by a group of fishers while bathing in the ocean. In the meantime, it seems that the Athenian elders have begun to try her in absentia for unspecified misdemeanours. Dicéphile appears at her house as a representative of the aréopage and Phryne playfully proposes that they enact the trial, an excuse for the extended seduction played out in the original one-act play described above. Nicias watches the scene in hiding and emerges with his friends to humiliate Dicéphile after he has collapsed amorously at Phryne's feet.

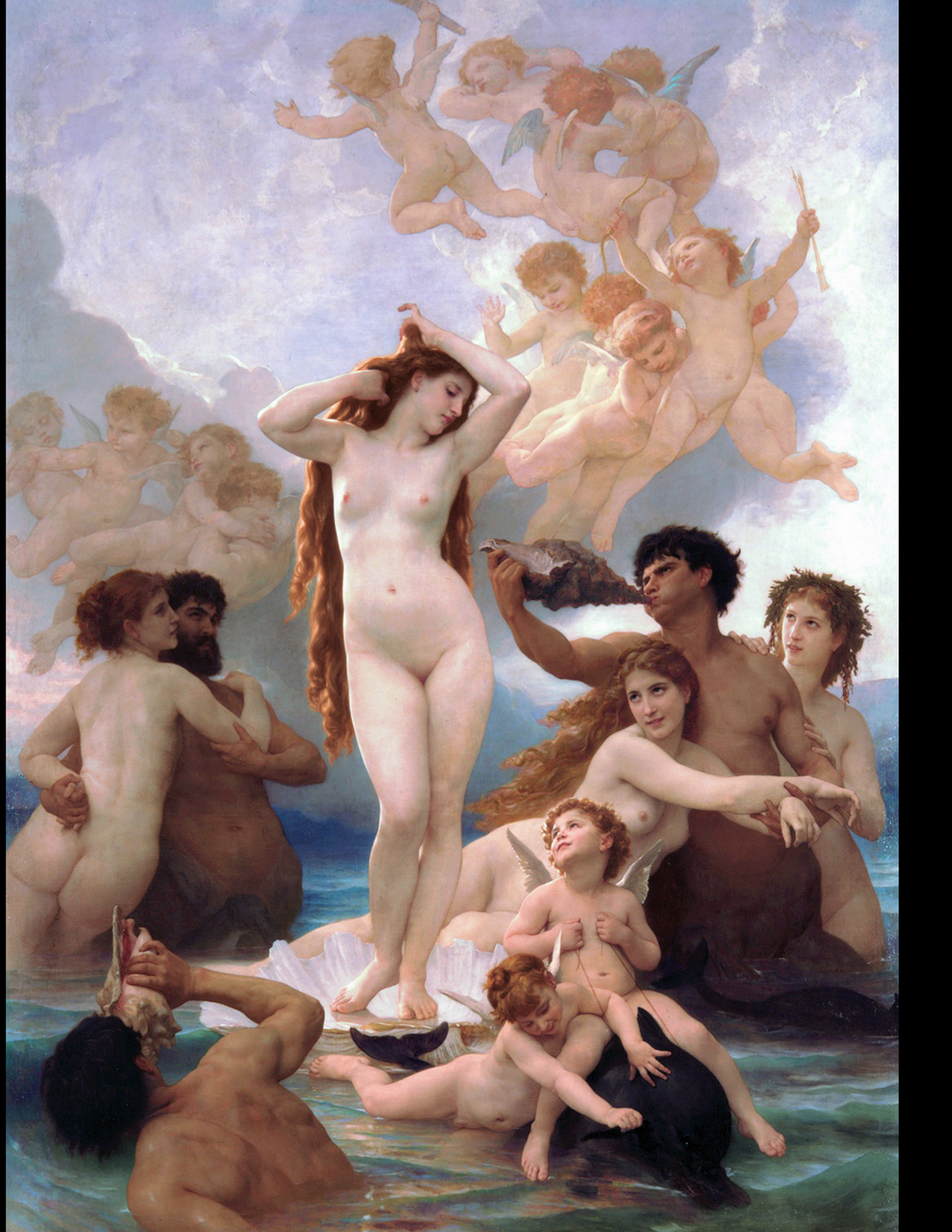

Two scenes in the opera depict confusion between the flesh-and-blood figure of Phryne and classical representations of Aphrodite: the narrative of the fishers and the conclusion. The first of these draws on a long iconographical tradition extending ultimately to Apelles's maritime image of Aphrodite Anadyomene. The most famous manifestation in the canon of Western art is Sandro Botticelli's Birth of Venus. Closer to our period, the French academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau engaged with this tradition in his La naissance de Venus, presented at the Salon in 1879 (Fig. 2), and Gérôme followed with the same subject in 1890 (not shown). Bouguereau adheres to Botticelli's long golden tresses and use of a shell as a pedestal but creates a full-frontal nude in place of the precursor's use of the pudica convention. A lesser-known academic painter named Joseph Blanc produced another version for the 1892 Salon, depicting Aphrodite Anadyomene as witnessed by two astonished fishers, one of whom falls to the ground in prayer (Fig. 3).Footnote 33 Although creating a much different atmosphere than Bouguerau's ornate, luxurious, and sentimental image, Blanc's painting manifestly seeks to resonate with this antecedent by depicting almost the same position of Aphrodite's arms. His figure also rhymes with the treatment of the female nude in Gérôme's Phryné devant l'aréopage and he more explicitly reminds the viewer that Phryne was the original model for Aphrodite Anadyomene by calling his painting Apparition de Phryné.

Fig. 2 William-Adolphe Bouguereau, La naissance de Vénus, 1879, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Fig. 3 Joseph Blanc, Apparition de Phryné, 1892

The libretto makes obvious reference to Blanc's painting. After having attended the Salon of 1892, Augé de Lassus or Saint-Saëns (or both) found a place for the episode in Phryne's account of her experience at the beach:

(My long hair floated / Caressed by the zephyrs. / The halcyons drifted by / Languid and weary. / Suddenly your great name resounded, Aphrodite. / It was thus they greeted me astonished, dumbfounded, / Those deluded fishers/who made the gods laugh. / Excuse their folly! / They had seen me, and it was you whom they saw, / As on that first day when, in your immense glory, / Your lovely body streaming with the tears of the briny waves, / You rose magnificent above the sea!)

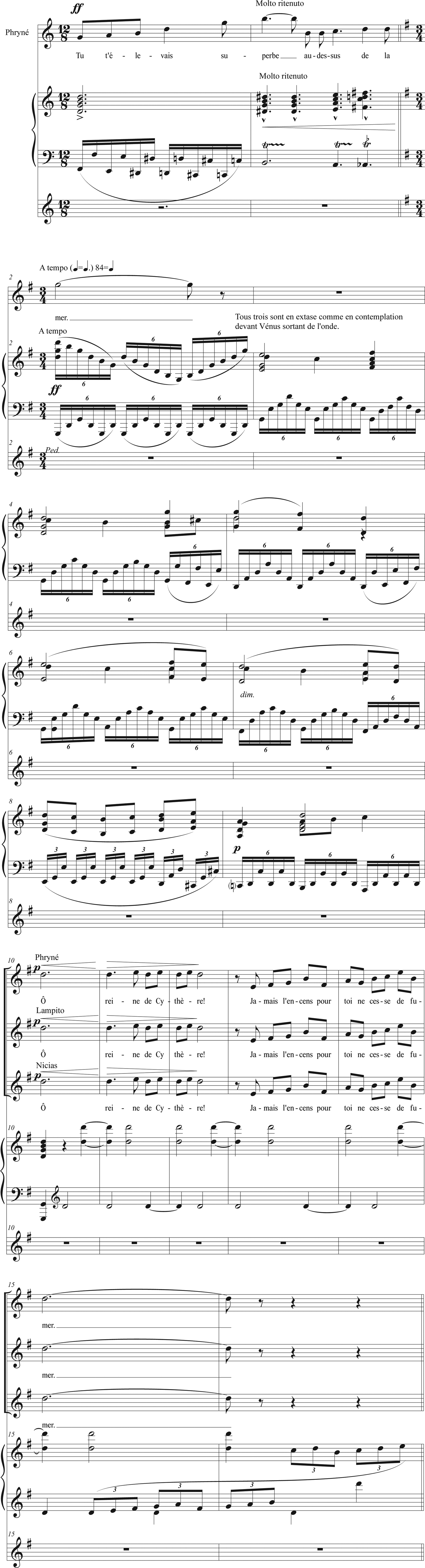

That the purpose of this narrative in the context of the libretto's story is not at all clear underscores an impression of wilful insertion intended to touch base with a venerable tradition. Saint-Saëns strongly responds to the maritime setting of Venus Anadyomene (Ex. 2) in a beautiful passage, the favourite piece of early reviewers, filled with evocative orchestral effects to depict the ocean water. Following a broad melody in 12/8 where the orchestra and voice combine symbiotically, Phryne builds to an impressive vocal climax on a high B followed by an impassioned orchestral peroration with a stage direction that does not appear in the libretto: ‘Tous trois sont en extase comme en contemplation devant Vénus sortant de l'onde’(All three [Phryne, Nicias, and Lampito] are ecstatic as if they are contemplating Venus emerging from the waves). Caught up in the image, they intone a homorhythmic prayer to the goddess in a moment of calm and worshipful stasis over a dominant pedal. (As a sidebar, note that Saint-Saëns's reading of the fisher's encounter with Phryne-as-Aphrodite seems consonant with the awe and fear of her judges in Gérôme's painting.) In his biography, Augé de Lassus recalled that Saint-Saëns found the scene challenging: ‘he wanted to rise to the level of this sublime revelation. He tried and initially failed, as perfection alone could satisfy him’. Later in the volume, the librettist noted that whereas Saint-Saëns's music for the entire score exhibited ‘exquisite grace’ and the laughter of an Aristophanes or Anacreon, the Aphrodite Anadyomene episode showed the composer could reach to ‘broader horizons’. Saint-Saëns confessed his difficulties in a letter to his librettist during the genesis: ‘My dear friend, I am done with this daunting piece showing Venus emerging from the waves, which has caused me much anxiety. It has now been fifteen days that I have turned it around in my head. I went first to listen to the soft murmur of the sea on the beach; I tried to render it musically; I began the scene but did not dare continue.’Footnote 34

Ex. 2 Camille Saint-Saëns, Phryné, Act II, Air et trio

The impression is that of a struggle to respond to the poetry of an image accorded the highest prestige in visual culture. The reference to classical art here occurs with the utmost respect. This is far from the world of opérette. Rather it speaks to the expanding affective range of opéra comique, which had long offered a path to a serious and intense emotional world (witness Mignon, Carmen, or Manon).

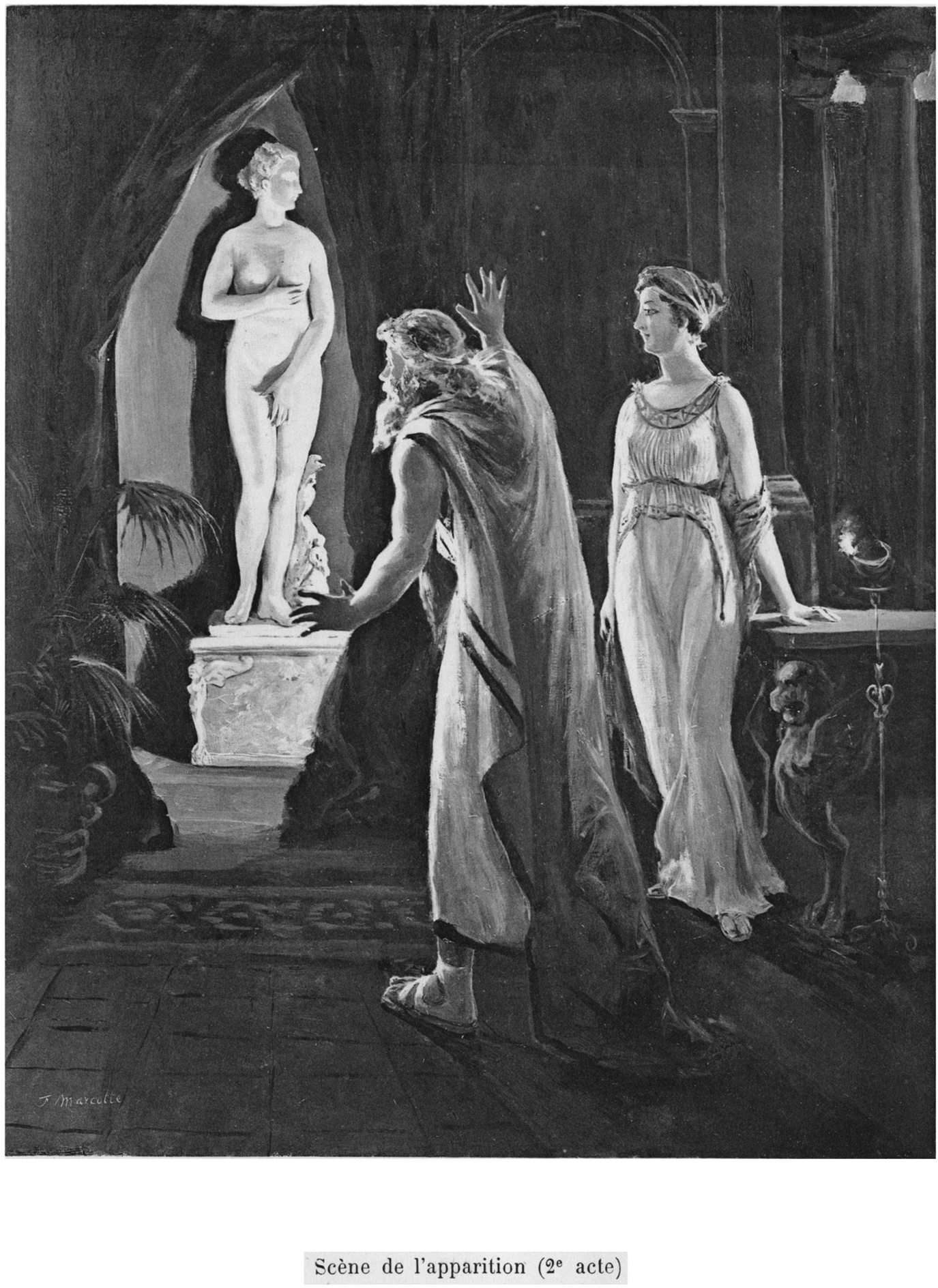

Classical representation of Aphrodite/Venus also plays an important part in the final episode, now with a real role in the unfolding of the plot. Whereas in the play a statue along the lines of the Venus de’ Medici is fully visible in Phryne's abode from the beginning of the seduction scene, in the libretto it is hidden by a curtain. At the culmination of the seduction, Phryne tells Dicéphile to get a rose for her from behind the curtain. She pulls aside, becoming invisible to him. The curtain opens to reveal the nude Venus de’ Medici with the facial features of Phryne. A mysterious light bathes the scene and voices sound from offstage. Dicéphile imagines that he is in the presence of Aphrodite herself: ‘Je t'adore, ô déesse, et tombe à tes genoux!’ (O Goddess, I adore you and fall at your knees). Completely enraptured he rushes to the little sanctuary to enfold the statue in his arms. The statue curtain suddenly closes, and he turns around to see Phryne (fully clothed) on the lit de repos. Confusing her with Aphrodite and unable to distinguish dream from reality, he falls to his knees and tugs at her arm. Nicias and his friends emerge from hiding, having caught the great moral arbiter in flagrante delicto.

Figure 4 shows the representation of this scene that was printed as the frontispiece to the vocal score of Phryné – not quite an accurate reflection of the libretto text because Phryne is meant to withdraw out of sight while Dicéphile interacts with the statue. On the face of it, this dramatic crux does not seem redolent of opérette. To be sure, Dicéphile is made to appear ridiculous. But he is merely a conventional boasting hypocrite of comedy and a made-up figure. Mistaken assumption about the real presence of Aphrodite informs Dicéphile's reaction as much as it does the elders of the Gérôme painting, though with Dicéphile the result is awestricken lust more than fear. Real classical matter itself does not come in for parody, desublimation, or disrespect. The prop of the Venus de’ Medici draws upon a great tradition. The problem of confusing marble with human flesh in the sculptural nude has driven debate since Hellenistic times, reverberating in Gautier's Symphonie en blanc majeur: ‘Le marbre blanc, chair froide et pâle / Où vivent les divinités’ (The white marble, flesh cold and pale / Wherein gods dwell). Charles Baudelaire at the beginning of La Beauté writes ‘Je suis belle, ô mortels! comme un rêve de pierre’ (I am beautiful, o mortals! like a dream of stone).

Fig. 4 Frontispiece, Camille Saint-Saëns, Phryné, opéra-comique en deux actes, piano-vocal score (Paris: Durand, 1893)

Of the final vision, Saint-Saëns wrote to Augé de Lassus that he had come up with ‘a mixture of sacred terror and voluptuousness that is not without charm’.Footnote 35 Saint-Saëns lends a magical aura to the setting of the revelation. As the stage darkens, a mysterious light (electricity was still rare on the operatic stage) emerges from the statue accompanied by strange harmonic progression on alternating strings and winds constructed of a sequence of minor-mode triads along a chromatically descending bass. A soft offstage chorus then intones a barcarolle over a dominant in the radiant and rare key of C-sharp major, avoiding resolution to the tonic as it leads to a sensual wafting between two half-diminished chords in a voicing like that of the Tristan chord at the beginning of Wagner's opera, an oft-encountered emblem of desire in late nineteenth-century music (bars 5–7, Ex. 3).

Ex. 3 Camille Saint-Saëns, Phryné, Act II, Scène de l'apparition

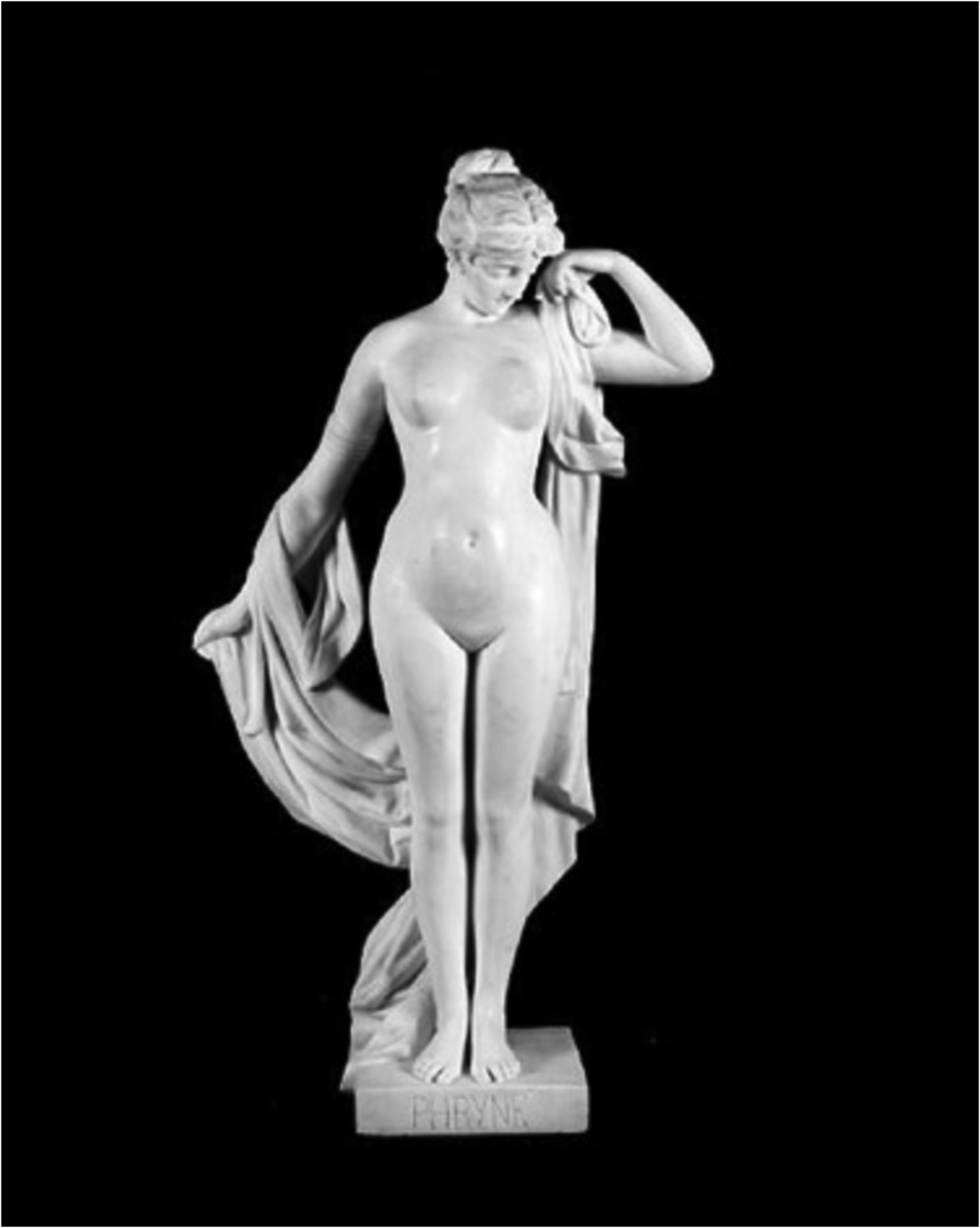

Once again, none of this suggests the irreverence of opérette. But wait. The frontispiece is not an accurate record of the work during its first run in another way besides recording the onstage presence of Phryne during Dicéphile's collapse. Although the libretto and score texts both clearly call for the statue of Venus/Aphrodite, the production took a different approach, probably at the instigation of the Opéra Comique director Léon Carvalho. He noticed a plaster cast rendering of Phryne by the sculptor Daniel Campagne at the Champs de Mars Salon at the beginning of May 1893 entitled Phyrné devant ses juges.Footnote 36 Because Carvalho needed a statue for his upcoming production, he asked permission from the administration of the Salon to borrow Campagne's work for a week so that the Opéra Comique designers could make a mould of it. The exposure made good business sense for Campagne who the next year received a commission for a marble version, ostensibly from a rich American admirer of Sybil Sanderson, the soprano who created the title role. Although, unfortunately, an image of the statue was not photographed at the time, small castings did circulate and are even available from dealers today (Fig. 5). This is the Phryne of the trial, appearing as herself so that Aphrodite is only implicitly present in an imagined reaction of the viewer. The pudica convention has been abandoned, as well as the bashful response of Gérôme's painting, though (unlike, say, Manet's Olympie) Campagne's Phryne does avert the gaze of the viewer.

Fig. 5 Daniel Campagne, Phryné devant ses juges, 1892

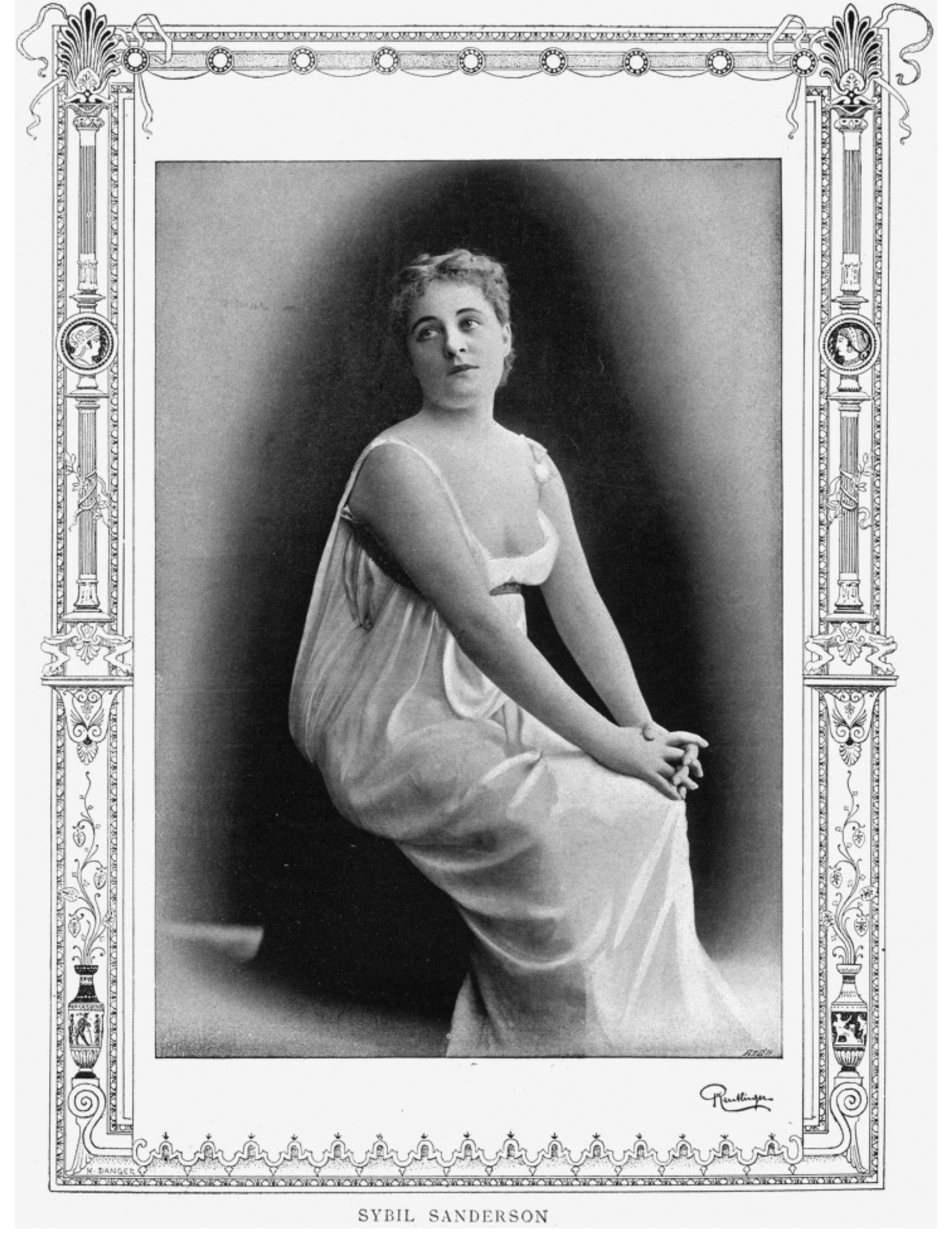

And gaze – the male gaze, like Gérôme's aréopage – was most certainly encouraged: the substitution of a flesh-and-blood figure for the plaster cast in this way made for a risqué moment at the Opéra Comique, especially given its traditional role as a venue for family fare. With works such as Carmen and Manon that reputation was seen increasingly as headed in a different direction. One of the most noted exponents of Massenet's Manon was Sibyl Sanderson, who with much fanfare also premiered the title role of Massenet's Esclarmonde (1889) and then later Thaïs (1894).Footnote 37 All were works where the composer and his librettists played up the sexuality of the heroine. Karen Henson has well described how Massenet championed Sanderson as a leading interpreter of his music, a strategy that effectively advanced her career but also had a distinctly exploitative side.Footnote 38 Beyond attestations of her vocal skills, marketing placed enormous emphasis on her attractiveness and sex appeal, a trait embedded in the prologue of Esclarmonde where Sanderson does not even sing at her first appearance in a chorus celebrating her magnificence. Such marketing created a loop with critical reception that only served exponentially to increase the obsession with her looks. Although the great soprano Emma Calvé was initially slated for Phryné, about two months before the premiere Carvalho reassigned the opera to Sanderson, who was still under contract to him and whom he had also pencilled in for creation of Massenet's Thaïs. Massenet was livid, but before long she was engaged at a much higher salary by the Opéra for the Thaïs premiere.Footnote 39 Given the discourse around Sanderson, the assignment of Phryne to her seems eminently understandable, despite the risk to the fortunes of Saint-Saëns's opéra comique because she would soon not be available.

The titillation of substitution in Phryné got extended from the ancient Phryne–Aphrodite pair to include a living singer, now rendered more salacious by breaking away from the Venus pudica statuary convention (Fig. 6). The pseudonymous Frimousse reported in Le Gaulois: ‘Blonde, smiling, in agreeable décolleté, Mlle Sanderson conquered all spectators, who asked nothing more than to be transformed into the aréopage’.Footnote 40 The society reporter for Le Journal wrote:

M. Saint-Saëns (and not you, Massenet, delightful master) M. Saint-Saëns shows the completely nude statue of Aphrodite to old Dicéphile and the dazzled spectators behind him. And all looks travel between the provocative Phryne near her lit de repos and the goddess. It is a back and forth, to and fro, between the marble that one dresses up and the actress whom one undresses.Footnote 41

Fig. 6 Sibyl Sanderson as Phryne, cover of Musica, June 1903

One cannot vouch for the good taste of such reporting, though even here the prurience of the moment is softened by reporting the subject of the statue as Aphrodite (following the libretto text) instead of Phryne. The society writer for Le Figaro even suggested a fantasy of Sanderson herself posing as a model:

In the story, this statue is attributed to Praxiteles. I do not know if the great Greek artist would disown it; but I can affirm that he never had a model as perfect as the divine Sibyl. The public in the theatre spoke with a single voice:

—The superb creature! … What shoulders! What arms! … What a profile! … What … What … What … And what a charming face!

—Yes, it's enough to make one want to study Phryne at home!

—Excuse me! It's so hot in here!Footnote 42

For Gil Blas, Richard O'Monroy wrote of Phryne emerging in marmoreal whiteness from among green plants on the stage: “Do not rejoice prematurely, cher lecteur, know that it is merely a statue’.Footnote 43 Henri Moreno of Le Ménestrel noted simply: ‘Unfortunately, at the right moment just when all opera glasses are prepared, she is replaced by a statue!’Footnote 44

The bawdy flavour belongs much more to the world of opérette than opéra comique. Zola accentuates the scopic in his account of Nana as Venus, who (unlike Sybil Sanderson) sings horribly. One real-life model for Zola's character, Hortense Schneider from La belle Hélène, sang better but achieved much notoriety through promiscuity (also unlike Sanderson … but perhaps more like the historical Phryne). Jean Claude Yon remarks that all opérettes antiques have a ‘high erotic charge’ and that the infiltration of courtesans into the milieu occurred in other works as well.Footnote 45 An episode with scanty clothing was de rigueur. The revealing galop infernal of the former became known as the French cancan with its high-kicking chorus line. And in both Orphée aux enfers and La belle Hélène sexuality is foregrounded through the loose morals of the gods.

***

In a relational view, where genre is evaluated by context and points of comparison – a referential field in continual flux – certain critics in some situations will find the element of titillation significant enough to call Phryné an opérette. Others, however, will want to say that Augé de Lassus and Saint-Saëns widened the frame of opéra comique to include a more risqué element. Listeners were (are and will be) informed to vastly different degrees about cultural connections and style. Critics may (or may not) factor in the quality of the verse, the reverential attitude towards cultural tradition, and the polish of Saint-Saëns's music. The generic attribution of the creators themselves will weigh more heavily for some than other factors.

On this last point: as already observed, we do know that for Saint-Saëns himself musical polish was decisive in distancing his work from opérette of Offenbach's ilk. The erotic element might even serve to remind of Offenbach's world only to underline the difference of Phryné. It was classy; Offenbach's works were not. Hugh Macdonald has already written evocatively about the many finely wrought passages in the score.Footnote 46 One cannot but admire the clever reharmonizations, purposeful archaicisms, smooth development of motifs, and transparent orchestration. Saint-Saëns would most certainly have been pleased by a critical framing of Phryné as an answer to Offenbach. From merely classy to classic: beyond craft, however one might define it, to my mind the association of Saint-Saëns with the aesthetic construct of classicism – which occurred increasingly as he aged – occupies an important place in the relational field around Phryné. It is not only a matter of touching base with classical canons of art, Praxiteles and Botticelli, but of musical style. In his review of Phryné for La nouvelle revue, the librettist Louis Gallet compared the fluidity of Saint-Saëns's handling of the orchestra to the orchestration of Mozart – there could be no more persuasive endorsement as a classic – and wrote of the ‘distinction, ease, and mastery’ (‘une distinction, une aisance et une maîtrise’) that had caused some to study his scores as the work of a classical master.Footnote 47 Alfred Bruneau opined, now disapprovingly, that ‘M. Saint-Saëns is a pure classic and all his steps have brought him closer to the classic, his teachers, his models, his sources of inspiration’.Footnote 48 Louis de Fourcaud wrote of ‘classique échos’ in the Phryné score: ‘The orchestra babbles like a frothy stream emerging from a Mozartian river’.Footnote 49 We can leave the last word to Augé de Lassus himself, who wrote of Saint-Saëns's style more generally:

Never excess. The Master imposes measure on himself while he also displays marvellous abundance. All of this is to connect his works to the masterpieces of harmony, measure, and focused perfection that classical antiquity reveals and transmits to us. Saint-Saëns knows how to write: one point, and that's all, where several notes would have been redundant and useless repetition.Footnote 50

Several perennial attributes of classicism emerge here: moderation, harmony, perfection, economy. Aesthetic qualities attributed to the ancients, then and now. Within the frame of reference of late nineteenth-century criticism, it is a discourse as dissonant to the world of Offenbach's opérette – who wanted polished, measured, and perfect at the Bouffes-Parisiens? – as absorbable by opéra comique.