What is the role of domestic political elites in shaping citizens’ legitimacy beliefs toward IOs? Some of the most prominent communicators about the merits and demerits of IOs have been domestic politicians. Consider well-known critics of IOs such as Rodrigo Duterte of the Partido Demokratiko Pilipino in the Philippines, Marine Le Pen of the National Rally in France, and Donald Trump of the Republicans in the US, or famous defenders of IOs such as Angela Merkel of the Christian Democratic Party in Germany, Carl Bildt of the Moderate Party in Sweden, and Fernando Cardoso of the Brazilian Social Democratic Party (SPD). IOs are not only contested among elites at the international level but also in domestic party debates on issues such as climate change, debt reduction, and free trade.

Yet, to date, domestic elites have received scant attention in existing research on the determinants of IO legitimacy. In the field of political communication, a rich body of literature has examined how party cues affect public opinion on domestic political issues, especially in the US (e.g., Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Slothuus and de Vreese Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Bisgaard and Slothuus Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018). Beyond the domestic setting, existing research is limited to a number of studies on how party cues shape public support for the EU specifically (e.g., Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Maier et al. Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012; Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Martini and Orriols2018) and on the effects of party cues on US public opinion regarding foreign policy (e.g., Berinsky Reference Berinsky2009; Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017; Cavarini and Feedman 2019).

In international relations, recent years have seen an upsurge of interest in the legitimation and delegitimation of IOs by various actors (Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). However, this literature has tended to overlook domestic political parties, focusing instead, as Chapter 4, on global elites, notably, nonstate actors (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Goetz, Scholte and Williams2000; Kalm and Uhlin Reference Kalm and Uhlin2015; Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Parajon and Powers2021), member states (Hurd Reference Hurd2007; Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015; Stephen and Zürn Reference Stephen and Zürn2019), and IOs themselves (Zaum Reference Zaum2013; Gronau and Schmidtke Reference Gronau and Schmidtke2016; Dingwerth et al. Reference Dingwerth, Witt, Lehmann, Reichel and Weise2019).

This chapter is an effort to bridge this gap by examining the effects of communication by domestic elites on IO legitimacy beliefs. We use the term “domestic elites” pragmatically to refer to elite actors who primarily aim to influence politics at the national level, and we concentrate on the role of political parties. The chapter aims to bring partisan politics into the debate over IO legitimacy and to shed new light on the importance of party cues for attitudes toward international cooperation. It complements the previous chapter on global elites by considering an alternative set of elites known to be influential in communication on domestic political matters. Identifying whether and when communication by political parties affects citizens’ perceptions of IO legitimacy is essential. With the rise of antiglobalist populist parties in many countries around the world, IOs have become politically contested in domestic politics like never before (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021). Getting a better grasp of how political parties shape legitimacy beliefs toward IOs can tell us something about the potential effects of this contestation for international cooperation, traditionally seen as dependent on domestic public support (Putnam Reference Putnam1988).

There are reasons to think that effects of party cues in the global setting are both stronger and weaker than effects of party cues in the domestic setting. On the one hand, citizens tend to be less familiar with global issues than domestic issues, and people can therefore be expected to rely on party cues as a heuristic to an even greater extent when forming opinions about global issues. On the other hand, foreign policy issues tend to be less politicized along party lines than domestic issues, suggesting that party cues may be less influential in shaping public opinion on global concerns.

Theoretically, we develop hypotheses about the effects of party cues on citizens’ legitimacy beliefs toward IOs and about the conditions under which those effects should be particularly strong. We derive three specific hypotheses, focused on general effects of party cues on IO legitimacy beliefs and conditioning effects arising from partisan identification and political polarization.

Empirically, we test these hypotheses through two survey experiments conducted in the US and Germany, which offer variation in the degree of political polarization. As in Chapter 4, we use vignettes to present the treatments to respondents. The vignettes consisted of descriptions of party positions in the US Congress and the German Bundestag. Two similarly designed experiments appeared in the same survey. One experiment focuses on party cues regarding military spending on NATO, and the other experiment on party cues regarding refugees accepted under the UN Refugee Convention.

We find that citizens draw on party cues when developing legitimacy beliefs toward IOs, but that these effects are conditioned by the political context and individual characteristics. Party cues matter almost exclusively in the US and hardly at all in Germany. This result suggests that party cues sway legitimacy beliefs more strongly in more polarized political environments.

In addition, citizens identifying with a specific political party who already have more positive opinions of the two IOs and the issues at hand are more easily influenced by “their” party’s cues. This result is found for all partisans studied. This indicates that Republican Party cues, for instance, are particularly influential among more positively predisposed Republicans, but do not get through to Republicans who care little for international cooperation. This chapter proceeds in five parts. It begins by developing hypotheses about how party cues are expected to shape legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. It then elaborates on the survey experimental design and presents the empirical analysis. We then turn to a discussion of the findings, offering interpretations of variation in effects. We end the chapter with a brief conclusion.

Hypotheses

We build on our theory (Chapter 3) to develop hypotheses about effects of party cues on citizens’ legitimacy beliefs. Our expectations rest on the assumption that citizens rarely have stable, consistent, and informed political attitudes and therefore may be susceptible to elite communication. Elite cues shape people’s opinions on an issue by simplifying choices for them, thus allowing them to overcome informational shortfalls.

An extensive literature in American and comparative politics shows that cues from political parties are particularly influential in shaping public opinion (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Slothuus and de Vreese Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017). The general idea is that people tend to follow cues from parties they sympathize with, while neglecting cues from parties they disagree with. This expectation is rooted in the dual recognition that citizens demand cognitive shortcuts to form political opinions and that parties fulfil central roles in structuring the choices that exist in domestic politics (Sniderman Reference Sniderman, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014).

The theory focuses specifically on so called “partisans,” that is, those citizens who identify with or lean toward a specific political party (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013, 61). Goren et al. (Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009, 806) well summarize the general logic of partisan influence on public opinion:

When someone hears a recognizable partisan source advocating some position, her partisan leanings are activated, which in turn lead her to evaluate the message through a partisan lens. If the cue giver and recipient share a party label, the latter will trust the former and accept the message without reflecting much on message content. But if the cue giver and recipient lie across the partisan divide, the recipient will mistrust the source and reject the message, again without much reflection.

We expect that party cues not only shape opinion formation in domestic politics but also international politics, as citizens form opinions of IOs. Citizens listen specifically to those elites they trust when they develop opinions about political issues. While citizens may listen to member governments, NGOs, and IOs on issues of global governance, as we explored in Chapter 5, we consider it likely that political parties, too, shape citizens’ opinions.

Political parties not only communicate about domestic concerns but also often take positions on international issues involving IOs as well. Consider, for instance, the communication by Donald Trump on NATO funding, Angela Merkel on EU economic governance, or Jair Bolsonaro on the constraints of the UNFCCC. Given the central role that parties occupy in structuring the choices that citizens confront, we expect their influence to extend to international issues as well. Evidence from the one IO where such dynamics have been systematically studied – the EU – suggests that this expectation is reasonable (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Maier et al. Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012; Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Martini and Orriols2018).

We develop three hypotheses about the effects of party cues on legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. The first hypothesis expresses the general expectation that party cues affect legitimacy beliefs toward IOs when citizens identify with that political party. Research on party cues in the domestic context suggests two complementary ways in which this happens (Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014). One perspective conceives of party cues as informational shortcuts that provide simple information which can guide citizens to form preferences (Carmines and Kuklinski Reference Carmines, Kuklinski, Ferejohn and Kuklinski1990; Sniderman et al. Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010). Citizens specifically follow the cues of those parties they tend to sympathize with, since the positions of those parties likely approximate the opinions citizens would have developed had they invested time and effort to form an opinion on their own. The other perspective suggest that party cues are influential because they activate citizens’ long-standing party loyalties and lead them to engage in motivated reasoning (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006; Slothuus and de Vreese Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010; Lavine et al. Reference Lavine, Johnston and Steenbergen2012; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). When citizens identify with a party, they are emotionally attached to it and will interpret new information in ways that confirm this affective relationship. The psychological process through which this occurs is motivated reasoning – the tendency to seek out information that confirms prior beliefs, to view evidence consistent with prior opinions as stronger, and to spend more time arguing against evidence inconsistent with prior opinions (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013, 59). While emphasizing different mechanisms, both approaches lead to the expectation that party cues will be effective in shaping the opinions of partisans.

H1: When citizens receive a message sponsored by a party they identify with and a conflicting message sponsored by another party, their legitimacy beliefs will be more likely to move in the direction of the message conveyed by the party they identify with than in the direction of the other party’s message.

Yet party cues may be varyingly effective under different conditions. This leads us to formulate two additional hypotheses (cf. Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). To begin with, we expect the strength of the party cue effect to depend on the degree to which citizens lean toward a particular party, that is, the level of partisan identification. When citizens identify more with a party, cues are more likely to present efficient informational shortcuts and to activate partisan loyalties, making citizens more likely to follow cues from this party. Conversely, when citizens identify less with a party, cues offer less certain informational guides for citizens and mobilize loyalties less, making citizens less likely to follow cues from this party.

H2: The effect of party cues predicted in H1 will be stronger among citizens with a stronger partisan identity than among citizens with a weaker partisan identity.

In addition, we expect the strength of the party cue effect to depend on the level of party polarization on the particular issue (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). In this context, party polarization is seen as having two components: the ideological distance between the parties on the specific issue and the ideological homogeneity within each party on this issue (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010, 118). Greater polarization entails that parties send clearer signals to citizens on where they stand. Thus, when issues are more polarized (i.e., parties are further apart and more ideologically homogenous), citizens are more likely to follow cues from party elites whose partisan orientation they share than when issues are less polarized (i.e., parties are positioned closer to each other and less ideologically homogenous). A number of studies in American politics find support for this expectation (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2012; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013).

H3: The effect of party cues (H1) will be stronger when party polarization on an issue is high (parties are further apart and more ideologically homogenous) than when party polarization on an issue is low (parties are positioned closer to each other and less ideologically homogenous).

Research Design

We test these hypotheses through two survey experiments designed to assess whether and when party cues shape legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. Below we present the design choices in detail.

Survey Design

Both experiments appeared in the same survey, conducted online among nationally representative samples of German and US respondents (N ≈ 2,000 per country), and implemented by YouGov during May 2019 (see Online Appendix A).Footnote 1 While many experiments of party cue effects in the domestic context focus on a single country, usually the US, we opted for two countries, as we wanted to assess our hypotheses in political systems with varying levels of party system polarization (Dalton Reference Dalton2008) and mass opinion polarization (Lupu 2015). It can be expected that party cues have stronger effects in countries with a higher level of party system and mass opinion polarization (such as the US) compared to countries with a lower level of party system and mass polarization (such as Germany) (Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Martini and Orriols2018, 505). While we recognize that these two countries also differ in other respects than polarization, the US and Germany are similar across several important contextual conditions. Both countries are advanced democracies, have federal political systems, are highly developed economically, are politically central member states in NATO and the UN, and have very high levels of Internet penetration.

In terms of political parties, we selected the historically two major parties in the federal parliament in both countries: the Democrats and the Republicans in the US and the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and the SPD in Germany. In the US, the Democrats and the Republicans make up the country’s two-party system, while, in Germany, the CDU/CSU and SPD are the largest catch-all parties (Volksparteien) in a multi-party system, even if they have lost in dominance over time.

Issue Selection and Frames

Our ultimate interest is the effect of party cues on people’s legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. For these purposes, vignette experiments are uniquely suitable, as treatments about different partisan framings of IOs and other political issues can be systematically varied in vignettes (e.g., Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). While one option would have been to formulate vignettes that focus directly and exclusively on IOs, we chose a different strategy. Usually, IOs are invoked in domestic political debates in relation to specific political issues, rather than as objects in themselves. For instance, the IMF is discussed in the context of financial stability, crises measures, and macroeconomic adjustment. Likewise, the UNFCCC is debated in association with climate change, emissions reductions, and adaptation measures. In addition, political parties seldom communicate political positions on the legitimacy of IOs per se, beyond supporting or contesting a state’s membership in an IO. We therefore chose to formulate vignettes that invoke IOs in the context of specific political issues, expecting the party cues expressed through these vignettes to sway people’s legitimacy beliefs toward the respective IOs.

One experiment focused on party cues regarding military spending on NATO, and the other experiment on party cues regarding reductions in the number of refugees accepted under the UN’s Refugee Convention. These two issues share several features that make them well suited to test our hypotheses (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). First, both issues received attention in public debates in Germany and the US prior to our study, as we discuss below. Second, both issues involved multiple considerations, such that parties and citizens could adopt different positions and opinions. Third, both issues were such that the main parties in the US and Germany tended to hold different positions, while the precise extent of those differences was not given, which allowed our treatments to vary the level of party polarization on the specific issues.

To substantiate vignette formulation, we conducted systematic content analyses using two large newspapers: The New York Times in the US and Die Zeit in Germany. The aim was to distil the main arguments that we could assign to the political parties in the vignettes about the respective IOs and to get information about the political polarization of the issue during the two years preceding data collection (2017 and 2018) (cf. Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). For this purpose, we searched the online databases of both newspapers through the LexisNexis platform and downloaded all articles that contained one or several key words. In the case of NATO’s funding system and increased financial contributions to NATO by European countries, we focused on NATO, funding, financing of NATO, European countries’ financial contributions, and the political parties in question. In the case of the UNHCR/UN’s Refugee Convention and the discussion about capping the number of refugees to be accepted under the convention, we searched for UNHCR, UN Refugee Convention, cap, number of refugees, limit number of refugees, and the political parties in question.Footnote 2 The search thus yielded articles that dealt with the issues in relation to IOs, or only with the issues, which offered an insight into the general debate about these issues independent of the IOs.

This content analysis allowed us to identify the main arguments that the parties were using in relation to these specific issues. We also coded how close the parties were in their opinions on both issues. We observed differences in rhetoric between the parties on the two issues, but still relatively close positions, especially in Germany. This is an advantage in terms of research design, as it allows us to present different arguments for each pair of parties on the same issue, while at the same time credibly varying the extent of party polarization on the specific issue.

Table 5.1 illustrates the issue frames in the NATO experiment in Germany and the US (see Online Appendix J1 for the full questionnaire and the wording of all vignettes). For the NATO experiment, our pro frame in Germany and the US emphasized the importance of NATO for maintaining peace, which would be undermined if restricting member state funding. On the con side, our frame in Germany concerned the trade-off between defense and welfare state expenses – both budgetary categories at the top of the German political agenda during 2017 and 2018 – while our frame in the US concerned lack of fairness in NATO funding, as the US shoulders the greater burden.

Table 5.1 Issue frames about NATO military spending

Supportive (pro) | Opposed (con) | |

|---|---|---|

Germany | Importance of NATO for peace | Trade-off between defense and welfare state expenses |

US | Importance of NATO for peace | Lack of fairness in funding NATO |

Table 5.2 summarizes the key content of the issue frames for the UN experiment. The pro frame stressed the need to honor Germany’s or the US’ commitment to protect refugees under UN Refugee Convention. The con frame emphasized the general costs of migration for the country.

Table 5.2 Issue frames about the UN Refugee Convention

Supportive (pro) | Opposed (con) | |

|---|---|---|

Germany | Need to honor Germany’s commitment to protect refugees under UN Refugee Convention | Costs of migration for Germany |

US | Need to honor US commitment to protect refugees under UN Refugee Convention | Costs of migration for the US |

While the content analysis was helpful in identifying applicable issue frames on the part of the parties, it also revealed contextual circumstances that should be noted. First, there was some variation in party polarization on these topics over time. For instance, the question of introducing a cap for refugees under the UN convention was a controversial issue in the German debate in the spring of 2018, but the debate then moved on to more general issues of restricting or increasing the inflow of refugees. Second, there was some amount of within-party debate. At times, and especially during the summer of 2018, media reported more about a conflict within the CDU/CSU than about a conflict between CDU/CSU and SPD. Third, while military expenditure and NATO were clearly linked to each other in public debates, migration was sometimes less distinctly tied to the UN specifically. The reason might be that the core mission of UN is not only to protect refugees, compared to NATO’s clear mandate to preserve peace.

Experimental Design

To isolate the causal effects of party cues, we randomly assigned individuals to groups that received different experimental treatments, in the form of vignettes, and a control group that did not receive any treatment. We context-adjusted vignettes according to issue and country, as described above. In addition, to make the experiment fit the German context, where the CDU/CSU are part of the same parliamentary group, but are two separate political parties, the vignettes refer to the parliamentary groups (“Bundestagsfraktionen”) of the CDU/CSU and the SPD, and not to the parties. In the US, the vignettes refer to Republicans and Democrats “in Congress.” The vignettes presented to the three treatment groups contained systematically varied information about the main arguments regarding the political issue, party endorsements, and party polarization on the issue (see Tables 5.3 and 5.4).

Table 5.3 Experimental conditions, NATO experiment in the US

Group | Vignettes |

|---|---|

Control group (N = 411):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. |

Treatment group 1 (N = 410):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. The main argument of those in favor of continuing current funding arrangements is that NATO is too important for peace to be weakened by financial disputes between the US and European states. The main argument of those opposed to continuing current funding arrangements is the lack of fairness in financial contributions to NATO by the US compared to European states. Republicans in Congress tend to oppose continuing current funding arrangements in NATO, while Democrats tend to favor continuing current funding arrangements in NATO. |

Treatment group 2 (N = 410):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. The main argument of those in favor of continuing current funding arrangements is that NATO is too important for peace to be weakened by financial disputes between the US and European states. The main argument of those opposed to continuing current funding arrangements is the lack of fairness in financial contributions to NATO by the US compared to European states. Republicans in Congress tend to oppose continuing current funding arrangements in NATO, while Democrats tend to favor continuing current funding arrangements in NATO. However, the partisan divide is not stark, as the parties are not far apart. Also, while Republicans tend to be opposed to a continuation and Democrats in favor, members of each party can be found on both sides of the issue. |

Treatment group 3 (N = 411):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. The main argument of those in favor of continuing current funding arrangements is that NATO is too important for peace to be weakened by financial disputes between the US and European states. The main argument of those opposed to continuing current funding arrangements is the lack of fairness in financial contributions to NATO by the US compared to European states. Republicans in Congress tend to oppose continuing current funding arrangements in NATO, while Democrats tend to favor continuing current funding arrangements in NATO. Moreover, the partisan divide is stark, as the parties are far apart. Also, not only do Republicans tend to be opposed to a continuation and Democrats in favor, but most members of each party are on the same side as the rest of their party. |

After each vignette, we asked a question measuring the outcome of interest: legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. We capture legitimacy beliefs using the measure of confidence in IOs introduced in Chapter 3. Both respondents in the control group and in the treatment groups received the question “How much confidence do you have in [IO] on a scale from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (complete confidence)?”

Tables 5.3 and 5.4 offer an example of the specific wording of the experimental conditions, using the NATO experiment as an illustration. The table also shows how we have sought to balance the number of respondents in each experimental group. Respondents were assigned the same condition in both experiments, since we were concerned that the degree of party polarization could otherwise be confusing and since this design makes it easier to assess any potential spillover effects (Transue et al. Reference Transue, Lee and Aldrich2009; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). The order of the experiments was block randomized for each respondent to reduce the likelihood of spillover effects from one experiment to another.

Table 5.4 Experimental conditions, NATO experiment in Germany

Group | Vignettes |

|---|---|

Control group (N = 404):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. |

Treatment group 1 (N = 398):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. The main argument of those in favor of continuing current funding arrangements is the importance of NATO for peace. The main argument of those opposed to continuing current funding arrangements is that the money would be better spent on social expenses such as education. The CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Bundestag tends to favor increasing German public defense spending and thus also increased financial contributions to NATO, while the SPD parliamentary group tends to oppose increasing German public defense spending at the extense of increasing social spending. |

Treatment group 2 (N = 401):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. The main argument of those in favor of continuing current funding arrangements is the importance of NATO for peace. The main argument of those opposed to continuing current funding arrangements is that the money would be better spent on social expenses such as education. The CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Bundestag tends to favor increasing German public defense spending and thus also increased financial contributions to NATO, while the SPD parliamentary group tends to oppose increasing German public defense spending at the extense of increasing social spending. However, the partisan divide is not stark, as the parties are not far apart. While the CDU/CSU parliamentary group tends to be in favor of an increase in financial contributions to NATO whereas the SPD parliamentary group is opposed, members of each party can be found on both sides of the issue. |

Treatment group 3 (N = 403):

| There have been a lot of recent discussions about member states’ financial contributions to NATO as a military alliance. Member states contribute to NATO through their national spending on defense. In 2017, the US spent 3.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, while a major European state like Germany spent 1.2 percent of its GDP. The main argument of those in favor of continuing current funding arrangements is the importance of NATO for peace. The main argument of those opposed to continuing current funding arrangements is that the money would be better spent on social expenses such as education. The CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Bundestag tends to favor increasing German public defense spending and thus also increased financial contributions to NATO, while the SPD parliamentary group tends to oppose increasing German public defense spending at the extense of increasing social spending. Moreover, the partisan divide is stark, as the parties are far apart. Not only does the CDU/CSU parliamentary group tend to be in favor of an increase in financial contributions to NATO whereas the SPD parliamentary group tends to be opposed, but most members of each party are on the same side as the rest of their party. |

The testing of all hypotheses relies on those respondents indicating some level of identification with a particular party (i.e., partisans), in line with our theoretical expectations (see also Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). H1 is tested by estimating if the difference in mean confidence between treatment group 1 and the control group is significantly different from zero. H2 is tested by checking whether the treatment effects for respondents in treatment group 1 depend on the strength of partisan identification. Specifically, we test H2 through effects on confidence of interaction terms between a treatment dummy for belonging to treatment group 1 (=1) and our variable measuring partisan identify strength. H3 is tested by assessing whether the treatment in treatment group 2 (low polarization) gives a weaker effect on confidence than the treatment in treatment group 3 (high polarization).

The two experiments were preceded by a measurement of the respondent’s pretreatment opinions regarding NATO and the UN. In both cases, the respondent was asked to rate the extent to which they believe the IO works effectively and democratically. In addition, each experiment is followed by manipulation checks (see Online Appendix J1). Respondents in treatment group 1 were asked to identify the main argument of the two parties on the issue in question. In addition, respondents in treatment groups 2 and 3 were asked to identify the degree of party polarization on the issue in question.

Finally, the survey included questions intended to measure a respondent’s cognitive mobilization, social trust, knowledge about global governance, confidence in domestic government, left–right ideology, and political party identification. In addition, YouGov provided demographic and political data on the respondents as background information, which we use for the purpose of balance tests: gender, age, and educational attainment.

Results

In order to understand the political opinion context in which these experiments were carried out, we begin by presenting descriptive data from the survey on respondents’ partisanship and pretreatment opinions toward the two IOs. We then turn to the results from the two experiments.

Partisanship

Figure 5.1 shows the percentage of partisans in Germany and the US. In the US, about 82 percent are partisans who identify with either the Democratic or the Republican Party, while, in Germany, about 77 percent identify with a political party. However, only about 32 percent identify with one of the two main parties in Germany – the CDU/CSU and the SPD. Overall, then, a considerably larger share of the population identifies with one of the two main political parties in the US compared to Germany.

Figure 5.1 Percentage of partisans in Germany and the US

Notes: Weighted percentages. Independents are those answering “don’t know” to the question of partisan identification.

Figure 5.2 shows the strength of partisan identities among those who indicate that they lean toward a particular party. In the US, about 73 percent of the partisans feel very or quite close to their political party, while, in Germany, about 69 percent feel very or quite close to their political party. Thus, the distribution of partisan identity strength is quite similar in the two countries. When we further disaggregate the distribution of partisan strength in the different parties, the distribution is very similar for different parties in both countries (see Online Appendix K).

Figure 5.2 Partisan strength in Germany and the US

Notes: Weighted percentages. This figure includes only those who indicated a partisan identification (Figure 5.1). “Don’t know” answers coded as missing.

The partisanship captured by these data should be understood in the context of the domestic political situation in these countries when the survey was conducted (May 2019). In the US, both the party system and public opinion have become more polarized in recent years. Polarization between the Democrats and the Republicans has been fueled by redistricting, shifts in public opinion, and the relative success of more extreme position-taking. As a result, the Democratic and Republican parties are increasingly far apart and more homogenous than in the past. Polarization also applies to public opinion. Over recent decades, US citizens appear to have become more firmly situated at either end of the left–right distribution, moving away from the middle ground (Abromowitz Reference Abromowitz2010; Pew Research Center 2014). In sum, increasingly polarized parties appear to function as sorting devices for an increasingly divided public.

In Germany, the CDU/CSU and the SPD have ruled together in a grand coalition since 2013, leading to a reduction in the level of polarization and open conflict between the two parties. Perceptions of a decrease in political polarization and a general shift to the left on the left–right spectrum may in turn have contributed to the rise of the populist far-right party AfD during the same period. The party first gained seats in the Bundestag in 2017, in the wake of the European migration crisis of 2015, and soon held seats in all sixteen regional parliaments (Landtage). The rise of the AfD reflects a general ideological movement in German politics toward the right, mainly at the expense of the SPD, which has lost voters to parties both on the right and the left. As our own data on partisan identification illustrate, the CDU/CSU and the SPD, once described as Volksparteien, no longer attract the large groups of partisans they once did (Figure 5.1).

Pretreatment Opinions

We also measured respondents’ pretreatment opinions toward the IOs and issues invoked in the experiments. There are striking differences among different partisan groups in the US (Figure 5.3). Democrats on average view NATO as more effective and democratic than Republicans (diff = 1.785 on a 11-point scale, N = 1,463, p < 0.000) and independents (diff = 2.047, N = 1,011, p < 0.000). Likewise, Democrats view the UN as more effective and democratic than Republicans (diff = 2.831, N = 1,554, p < 0.000) and independents (diff = 1.983, N = 1,078, p < 0.000). Opinion appears especially polarized when it comes to the question of accepting refugees as a moral obligation of the US, which an overwhelming majority of Democrats tends to strongly agree with, and an overwhelming majority of Republicans tends to strongly disagree with (diff = 3.589, N = 1,622, p < 0.000). Similarly, a majority of Democrats tends to strongly disagree with the statement that defense spending should be prioritized to ensure the national security of the US, while a majority of Republicans tends to strongly agree with this statement (diff = −4.872, N = 1,647, p < 0.000). Differences between Democratic partisans’ opinions and independents’ opinions are slightly smaller than differences between Democrats and Republicans, but still substantial (diff = 2.924, N = 1,174, p < 0.000 for “accepting refugees” and diff = −1.358, N = 1,138, p < 0.000 for “defense spending”).

Figure 5.3 Pretreatment opinions in the US, by partisan identification

Notes: Weighted means. “Don’t know” answers coded as missing.

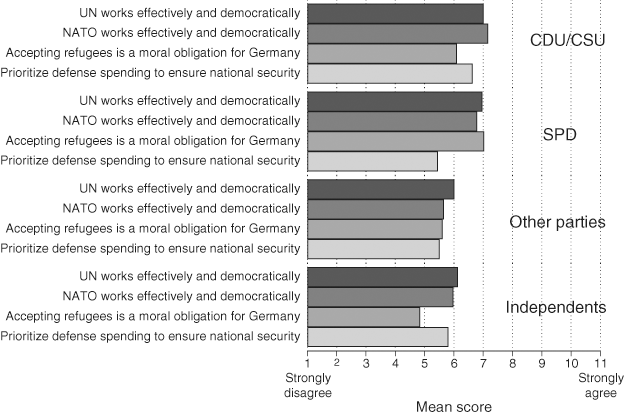

In Germany, opinion is less polarized across these four items than in the US (Figure 5.4). Figures for both NATO and UN support are comparable between CDU/CSU and SPD partisans. While CDU/CSU and SPD partisans do not differ on whether the UN works democratically and effectively (N = 593, p < 0.760), CDU/CSU partisans on average believe more in NATO than SPD partisans (diff = 0.345, N = 582, p < 0.039). Interestingly, SPD partisans support the UN (diff = 0.588, N = 1,361, p < 0.000) and NATO (diff = 0.620, N = 1,342, p < 0.000) more than those who identify with other political parties. In addition, SPD partisans support the UN (diff = 0.836, N = 523, p < 0.000) and NATO (diff = 0.811, N = 510, p < 0.000) more than the independents. This suggests that SPD and CDU/CSU partisans are less polarized when compared to each other than when compared to citizens with other or no partisan identification.

Figure 5.4 Pretreatment opinions in Germany, by partisan identification

Notes: Weighted means. “Don’t know” answers coded as missing.

The issue of accepting refugees as a moral obligation of Germany is slightly more contentious among Christian and Social Democrats: SPD partisans on average agree slightly more with this statement than CDU/CSU partisans (diff = 0.830, N = 623, p < 0.000), people with another partisan identification (diff = 1.182, N = 1,442, p < 0.000), and independents (diff = 2.136, N = 628, p < 0.000). Conversely, prioritizing defense spending to ensure the national security of Germany is a statement that SPD partisans tend to disagree with, while CDU/CSU partisans (diff = −1.173, N = 609, p < 0.000) and people with another partisan identification tend to agree with it (diff = 0.459, N = 1,404, p < 0.021). The difference in SPD partisan’s opinion on this issue compared to independents is not statistically significant (N = 584, p < 0.129). Taken together, the differences in opinion between citizens with different partisan identifications in Germany are much smaller than in the US.

Again, it is important to understand these figures in context. In recent years, both security and migration have been relatively politicized topics in the US and Germany, as revealed by our media content analysis. In terms of policies toward the two IOs, the governments of the two countries pursued quite different approaches at the time when our survey was conducted. The US saw a period of increasing disengagement from multilateral institutions under the Trump administration (Republican), while Germany under the leadership of Angela Merkel (CDU) continued to support the institutions of the liberal international order.

Experimental Results

Having presented the political opinion context in which the experiments were conducted, we now move to a presentation of the results. We discuss the results for each hypothesis in turn for each country separately and then report a series of robustness checks. We estimate treatment effects by analyzing the difference in means between the control group and the treatment groups, respectively, using OLS regression of confidence on a treatment dummy (1 = treated) based on weighted data. We also compare across treatment conditions when necessary to assess specific hypotheses. As our results on both IOs are very similar, we present them in tandem. We begin by reporting the results for the US and then move on to the results for Germany.

H1 predicts that party cues will affect legitimacy beliefs toward IOs when citizens identify with the political party issuing the message. For this purpose, we separated Democrat and Republican respondents in the US to detect the different effects of party endorsements hypothesized for each set of partisans. We find mixed evidence for H1. Figure 5.5 shows that party cues work well among Democrats in the context of both IOs. For these respondents, the treatment effects are positive and statistically significant across the board, irrespective of the information provided about the level of polarization. Among Democrats, the endorsement of NATO as a preserver of peace that needs continued funding (treatment 1) increases confidence in the IO by about 0.9 on the 11-point confidence scale, and the endorsement of the UN as a protector of refugees (treatment 1) increases confidence in this IO by about 0.5. In contrast, for the Republicans, we only find a negative and statistically significant treatment effect in the context of NATO and when coupled with information about high polarization on this issue.

Figure 5.5 Effects of communication among partisans in the US

Notes: Average treatment effects with their respective 95 percent confidence intervals. Weighted data. Treatment group 1 received issue frame and party endorsement; group 2 received issue frame and party endorsement in a low polarization environment; and group 3 received issue frame and party endorsement in a high polarization environment.

H2 anticipated that the effects of party cues predicted in H1 would be stronger among those citizens with a stronger partisan identity. We again find mixed evidence for this hypothesis. Table 5.5 shows the results for the Democrats, while we refrain from showing the results for the Republicans, which do not offer support for this expectation in the context of any of the two IOs (results are available in Online Appendix L). The evidence from the Democrats corroborates H2 in the context of NATO, where larger treatment effects are consistently found among Democrats with a stronger partisan identity. Irrespective of the information provided about the level of polarization on the issue (treatments 1–3), respondents with a stronger identification with the Democratic Party appear more greatly affected by the party endorsement of NATO, indicated by the statistically significant and increasingly large coefficients. By contrast, we do not find evidence of such a conditional effect of partisan identity strength on confidence in the context of the UN.

Table 5.5 Effects of party cues among Democrats in the US, by partisanship strength and IO

NATO | UN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Party cues (1) | Party cues, low pol. (2) | Party cues, high pol. (3) | Party cues (1) | Party cues, low pol. (2) | Party cues, high pol. (3) | |

Treated × Not at all close | 2.020 | 2.523 | 1.131 | 3.263 | 0.070 | 1.789 |

(1.814) | (1.441) | (1.277) | (1.778) | (1.792) | (1.647) | |

Treated × Not close | 2.267* | 3.285** | 2.823* | 1.250 | 1.621 | 1.555 |

(1.127) | (1.134) | (1.131) | (1.620) | (1.634) | (1.630) | |

Treated × Quite close | 3.679*** | 3.211** | 3.309** | 2.314 | 2.275 | 2.233 |

(1.100) | (1.095) | (1.103) | (1.602) | (1.596) | (1.598) | |

Treated × Very close | 3.879*** | 4.530*** | 3.403** | 2.597 | 3.174* | 2.486 |

(1.118) | (1.116) | (1.165) | (1.612) | (1.611) | (1.646) | |

Constant | 3.563** | 3.563** | 3.563** | 4.217** | 4.217** | 4.217** |

(1.079) | (1.079) | (1.079) | (1.585) | (1.585) | (1.585) | |

N | 324 | 317 | 311 | 325 | 324 | 316 |

Adj. R2 | 0.150 | 0.162 | 0.106 | 0.114 | 0.144 | 0.096 |

H3 anticipated that the effects of party cues predicted in H1 would be stronger when issues are presented as more politically polarized among the two parties. Two types of evidence would be consistent with this expectation. First, if there is a significant effect of party cues in the case of high polarization of an issue (treatment group 3) but not in the case of low polarization of an issue (treatment group 2). Second, if there are significant effects of party cues under the condition of both high and low polarization and there is a significant difference in the size of the effect between treatment groups 2 and 3. The preferred test statistic for this second test is a t-test of statistical significance of the difference between the coefficient of the treatment effect in group 2 and the coefficient of the treatment effect in group 3:

(1)

(1)where b1 is the first coefficient and b2 is the second coefficient, with their respective standard errors.Footnote 3

These tests yield mixed evidence for H2. First, among Republicans, there is a statistically significant effect in treatment group 3, but not in treatment group 2, in the context of NATO, consistent with the expectation. When Republican partisans receive the message that Republicans in Congress oppose current funding arrangements in NATO, and that this issue is highly polarized, this information reduces their confidence in NATO by about 0.6 on the 11-point confidence scale. Second, among Democrats, both treatment groups 2 and 3 show significant effects in the context of both IOs. However, a t-test indicates that the difference in treatment effects between the two groups is not statistically significant (p < 0.235 for NATO; p < 0.391 for the UN).

We now turn to the results for Germany (Figure 5.6). We find some evidence for H1, expecting party cues to affect the legitimacy beliefs of partisans. Among CDU/CSU partisans, we observe one positive and statistically significant treatment effect in the case of NATO, in line with H1. When CDU/CSU partisans are conveyed the message that the CDU/CSU parliamentary group advocates an increase in the financial contribution to NATO, because of the organization’s importance for peace, this affects their confidence in NATO positively when the issue is highly polarized. However, we also observe similar positive treatment effects among CDU/CSU partisans in the case of the UN, despite the expectation of negative effects from a treatment indicating the CDU/CSU parliamentary group to advocate a reduction in the need of refugees under the UN convention due to costs. We do not find any significant treatment effects for SPD partisans.

Figure 5.6 Effects of communication among partisans in Germany

Notes: Average treatment effects with their respective 95 percent confidence intervals. Weighted data. Treatment group 1 received issue frame and party endorsement; group 2 received issue frame and party endorsement in a low polarization environment; and group 3 received issue frame and party endorsement in a high polarization environment.

There is no support for H2 in the German context. Party cues do not have a greater effect on respondents with a stronger partisan identification, regardless of whether we focus on CDU/CSU or SPD partisans, and regardless of whether we explore this expectation in the context of NATO or the UN (detailed results are in Online Appendix L).

Finally, we find mixed evidence in favor of H3, about a conditioning effect of issue polarization, when considering the two types of evidence indicated above (Figure 5.6). First, among CDU/CSU partisans, the endorsement of NATO as a preserver of peace, combined with high issue polarization (treatment group 3), increases confidence in NATO by about 0.8 on the 11-point confidence scale, while there is no effect in the context of low polarization (treatment 2), consistent with H2. The treatment effects are nonsignificant among SPD partisans. Second, among CDU/CSU partisans, both treatment groups 2 and 3 show significant effects in the context of the UN. However, a t-test (Equation 1) indicates that the difference in treatment effects between the two groups is not statistically significant (p < 0.378).

As a complement to the hypothesis tests, we also explored whether the treatment effects were statistically significant among independents. We did not find any statistically significant treatment effects in either country.Footnote 4 In addition, we examined whether treatment effects are dependent on respondents’ level of political awareness, using the two indicators of education and knowledge regarding global governance. The results indicate that treatment effects are stronger among more politically aware Democrats, while no such contingent effect was found for Republicans. In Germany, results are not found to depend on any of the political awareness indicators (see Online Appendices L4–L7).

Taken together, we find strong support for H1 on general party cue effects among Democrats in the US, some support among Republicans in the US and CDU/CSU partisans in Germany, and no support among SPD partisans in Germany. H2 on a conditional effect of partisan identification receives support among Democrats in the US in the context of NATO, but not in the context of the UN, and not for other partisans in the two countries. H3 on a conditional effect of issue polarization receives support among Republicans and CDU/CSU partisans in the context of NATO, but not among Democrats and SPD partisans in relation to any of the two IOs.

Validity and Robustness Checks

To test the validity of the data, we performed balance tests. Specifically, we examined whether eight different individual characteristics measured in the survey, including age, gender, education, and social trust, are evenly distributed across the conditions we aggregated for the analysis. The results increase our confidence in the randomization of the subjects among treatment groups. We only discover imbalances in one of the forty-eight tests (see Online Appendix M1).

In addition, we conducted a range of robustness checks, which corroborate the main results. First, we included a series of manipulation checks to ensure that respondents had properly registered the information on party endorsements and level of polarization. Respondents in treatment group 1 were asked to identify the main argument of the two parties on the issue in question. In addition, respondents in treatment groups 2 and 3 were asked to identify the degree of party polarization on the issue in question. In the US, where the political climate is more polarized and people thus may be more alert to information about party positions, the manipulation checks worked better. In the context of NATO, on average almost 79 percent of respondents correctly recalled the pro and con positions of the Republicans and 82 percent the positions of the Democrats. In the context of the UN, on average almost 83 percent of respondents correctly recalled the pro and con positions of the Republicans and 82 percent the positions of the Democrats. We also asked respondents if they recalled the level of polarization between the two political parties on the issues of migration and security. About 75 percent of the respondents correctly recalled high polarization, while only about 38 percent correctly recalled low polarization in the context of NATO. About 85 percent of the respondents correctly recalled high polarization, while only about 30 percent correctly recalled low polarization in the context of the UN. Moreover, the results from t-tests of the polarization comprehension checks confirmed for both experiments that both of our polarization conditions prompted significantly higher perceptions of polarization (N = 820, p < 0.000 for both experiments).

In Germany, manipulation checks yielded somewhat weaker results. In the context of NATO, on average 70 percent of respondents correctly recalled the pro and con positions of the CDU/CSU and 75 percent the positions of the SPD. In the context of the UN, however, much fewer respondents correctly recalled party endorsements, which may have to do with the less clear partisan divide between the CDU/CSU and the SDP on this issue in public debate. About 25 percent correctly recalled the CDU/CSU position, while about 30 percent correctly recalled the SDP position. When we further asked respondents across conditions about the extent to which they thought the parties were polarized, recall accuracy in the context of NATO was 58 percent for the weakly polarized condition and 66 percent for the highly polarized condition. In the context of the UN, 58 percent correctly recalled low polarization and 68 percent high polarization. The results from t-tests of the polarization comprehension checks for both experiments confirmed that our high polarization prompts led to significantly higher perceptions of polarization (N = 804, p < 0.001 for both experiments).

Given these results from the manipulation checks, it is warranted to test for the robustness of the results by reanalyzing the results from Figures 5.5 (US) and 5.6 (Germany) only using the answers of those who passed at least one of two manipulation tests about the partisan endorsements per experiment. The results are robust throughout with one exception: In Germany, the NATO cue in a highly polarized context (treatment group 3) does not affect the confidence of CDU/CSU partisans in NATO (Online Appendices M2–M3).

Second, we explored the results in more depth by checking whether treatment effects differ among those who have more negative or positive pretreatment opinions of democracy and effectiveness in the two IOs. It might be that those with negative opinions are firmer in their stances and less easily influenced by elite communication. To test this, we examine whether our experimental results differ across pretreatment beliefs on our two IOs for partisan groups separately. For example, we investigate whether Republican Party cues are particularly influential among more positively predisposed Republicans, but do not get through to Republicans who care little for international cooperation. Indeed, all treatment effects are larger in size among those with more positive opinions of the two IOs compared to those with more negative opinions. This result holds in both countries. Thus, respondents who already have a positive impression of IOs react more strongly to party cues about IOs (see Online Appendices M1–M2).

Third, we checked whether treatment effect size differs depending on pretreatment attitudes toward defense spending and refugees. In the US, treatment effects on UN confidence are larger in size among those who think that accepting refugees is a moral obligation of the US. In the context of NATO, treatment effect size is not different among people with varying positions on whether defense spending should be prioritized. In Germany, effects depend on pretreatment attitudes across the board. Treatment effects on confidence in NATO are consistently stronger among those who agree defense spending should be prioritized, and treatment effects on confidence in the UN are consistently stronger among those who agree accepting refugees is a moral obligation of Germany (see Online Appendices M3–M4). In sum, citizens who already care more deeply about the two issues, also tend to be more receptive to party cues on these matters.

Finally, we checked whether treatment effect size depends on confidence in government. We find that treatment effects are stronger among those respondents who have relatively more confidence in government in both countries (see Online Appendices M5–M6).

Discussion

Taken together, the results from two experiments conducted in Germany and the US suggest that party cues may work as heuristics for forming legitimacy beliefs toward IOs, but that the effects are heterogeneous. In other words, party cues work better under some conditions than others. In the following, we discuss how we may understand this variation in our findings.

First, why do party cues appear to have stronger effects on people’s legitimacy beliefs in the US compared to Germany? We attribute this variation in effects across the two countries in part to variation in the degree of political polarization across the two countries, both in terms of party system polarization and mass polarization.Footnote 5 The US two-party system is considerably more polarized than the German multiparty system, in the sense that parties are ideologically more differentiated in the US than in Germany (Hetherington Reference Hetherington2001; Dalton Reference Dalton2008). In the more polarized system, the positions of the parties are more distinguishable from one another, and thus clearer and less ambiguous as cues for their partisans (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). While the American and German respondents in our experiments received equally distinguishable cues, the greater polarization between the two US parties likely made the differences between these two sets of party cues more credible in the US than in Germany, as indicated by the stronger recollection of party endorsements among US respondents (see robustness checks).

In addition, public opinion in the US is more ideologically polarized than in Germany (Lupu Reference Lupu2015). When the public is more clearly divided in ideological terms, citizens are also more likely to listen to their favored political party when it conveys messages that conflict with those of parties on the other side of the spectrum (Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017). General differences in mass polarization between the two countries apply to the partisans in our experiment as well, which are positioned closer to the extremes on the left–right continuum, and identify more strongly with their party (Figure 5.2), in the US than in Germany. This polarization extends to respondents’ pretreatment opinions of the two IOs as well. While pretreatment beliefs about whether the UN works democratically and effectively did not differ among CDU/CSU and SPD partisans in Germany, they clearly do in the US among Democrats and Republicans. And while pretreatment beliefs about how well NATO works differed among CDU/CSU and SPD partisans in Germany, they do so to a much larger extent in the US among Democrats and Republicans.

Second, how come party cues worked better in shaping the opinions of partisans identifying with some political parties than others? In the US, the results show a significant difference between Democrats and Republicans in terms of cueing effects on legitimacy beliefs (see also Brutger and Clark Reference Brutger and Clark2022), while in Germany, such effects are more common for CDU/CSU partisans compared to SPD partisans, although sometimes in the opposite direction than expected. In the US case, one reason might be found in the pretreatment opinions toward IOs. As revealed by the robustness tests, party cues had considerably stronger effects on citizens who already had a positive opinion of these two IOs, and those citizens were on average much more common among Democratic partisans. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that the only example of a party cue effect among Republicans is found in the context of NATO, which Republicans tend to view more favorably. These results tie in with findings in recent research that people’s prior opinions on international issues affects their responsiveness to elite cues (Spilker et al. Reference Spilker, Nguyen and Bernauer2020).

In the German case, the differences in pretreatment opinions between CDU/CSU and SPD partisans are nonexistent regarding the UN and small regarding NATO, and thus offer little help in accounting for the greater sensitivity of CDU/CSU partisans to party cues. The puzzling finding that CDU/CSU partisans move in the opposite direction from the party cue on the UN migration regime may be explained by the relatively high support among these partisans for the UN as an organization and for the notion that Germany has a moral obligation to accept refugees (see Figure 5.4), which may have trumped the economic concerns emphasized in the party cue. Such effects are not uncommon and usually interpreted as issue substance outweighing party cues (Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013).

Third, what may account for party cues being more effective in relation to some issues than others? In both countries, party cues about military spending in the context of NATO had stronger effects than party cues about migration in the context of the UN. However, this pattern may very well be due to different reasons in the two countries. In the US, Democratic and Republican partisans are already positioned exceptionally far from each other in terms of pretreatment opinions toward the UN and the obligation to accept refugees (Figure 5.3). The already extreme positions of partisans on this issue mean that the room for further shifts in opinion toward the end of the spectrum is limited. It may also be that these extreme positions of partisans are anchored, making further movements less likely and far-reaching (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974). In Germany, conversely, the media content analysis and the manipulation check suggest that the ineffectiveness of the UN cues may be due to the limited differences between the two main parties on this issue in the public debate, making the treatments less credible and the party cues more difficult for respondents to recall.

Fourth, the findings reported in the robustness tests suggest that some citizens are more responsive to party cues than others, irrespective of country, partisan identity, and issue focus. In both countries, the effects of party cues are reinforced among people with more confidence in the national government. Conversely, people who have lost faith in the government appear to simply dismiss cues from parties. This finding highlights the causal importance of confidence in national government for legitimacy belief formation, in line with a growing public opinion literature on attitudes toward the EU (e.g., Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Meer and De Vries2013; Chalmers and Dellmuth Reference Chalmers and Dellmuth2015; Schlipphak Reference Schlipphak2015; Dellmuth et al. Reference Bexell, Jönsson and Uhlin2022a). Another pattern in both countries is the greater receptivity to party cues among people with more positive opinions toward IOs to start with. Related, party cues were more effective in both countries among people with more positive opinions of the two issues invoked in the context of international cooperation (accepting refugees, spending on security). This suggests that people who think of IOs as relevant governing institutions, and who care about the issues at stake, also are willing and able to integrate new information about these organizations and issues from parties they sympathize with. Finally, in the US, political knowledge about global governance amplifies the effects of party cues in the expected direction among Democratic but not Republican partisans. This result is consistent with research indicating that politically aware individuals are more likely to understand and integrate new information into their opinions (Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003). Taken together, these findings suggest that party cues are of varying importance for citizens’ formation of legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. Among citizens who trust political institutions, have positive expectations on IOs, care more about the issues of cooperation, and have more knowledge of global governance, party cues are effective in shaping opinions. Conversely, when citizens have lost faith in political institutions, think little of IOs, care little about the issues of cooperation, and have less knowledge of global governance, party cues matter little for their opinion formation toward IOs.

Conclusion

Taken together, this chapter suggests that citizens draw on party cues when developing legitimacy beliefs toward IOs and that those effects are stronger in countries which are more polarized politically. The two experiments focused on party positions in the US Congress and the German Bundestag found that cues mattered almost exclusively in the US context, and then mainly among Democrats, while Republicans appeared less easily swayed. The experiments also offered mixed support for the expectations that party cue effects depend on the strength of citizens’ partisan identification and the polarization of the issue between and within political parties. However, examining pretreatment opinions, the robustness checks contributed important insights, partly correcting the more negative findings in the main analysis. Specifically, it appears that party cues have effects on citizens in both countries, sympathizing with both parties, when these citizens already have more positive opinions of NATO and the UN, more positive views of the issues at hand, and more confidence in their domestic government.

These findings suggest three broader observations. First, they show that domestic political elites play an important, albeit varying, role in citizens’ development of legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. While Chapter 4 established that communication by global elites, in the shape of member governments, NGOs, and IOs themselves, affect the perceived legitimacy of IOs, this chapter shows that party elites may have a similar impact. As political parties engage in growing contestation over IOs, challenging and defending their authority (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021), citizens will take notice, especially when they care about international cooperation. Partisan politics is not divorced from the legitimacy of IOs, but a force shaping its future development.

Second, the findings indicate that party cue effects in general may be weaker on global issues compared to domestic issues. While it would have been reasonable to expect that citizens would rely more on party cues on global issues they know less well, the mixed picture in our findings suggests the opposite, possibly because global issues often are less politicized than domestic issues. The stronger effects of party cues established in the context of US politics (e.g., Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013) and European politics (e.g., Maier et al. Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012; Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Martini and Orriols2018) may thus be due to greater politicization and polarization of these issues among parties and the mass public compared to the legitimacy of IOs.

Third, our findings highlight the importance of extending experiments on elite cueing beyond single-country settings, particularly the US. Most experiments on the effects of elite cueing on public opinion toward international issues and institutions focus exclusively on the US (e.g., Hiscox Reference Hiscox2006; Berinsky Reference Berinsky2009; Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017). The same goes for the large literature on party cueing in the context of American politics (e.g., Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017). This chapter points to the perils of this strategy, as the US is a very particular case, due to the high level of polarization in the party system and the mass public. We can only expect findings from the US setting to travel to those rare contexts which share these features; in other contexts, the effects of party cueing may very well be weaker.