Introduction

One of the foundational elements of democracy is the ability for citizens to choose freely among different candidates for office in legitimate elections. It is essential to have choices at the ballot box in order to accurately represent constituents’ changing interests, and without choices, a shifting electorate may not receive adequate representation. For example, if incumbents are consistently reelected due to a monetary advantage, potential candidates who could better represent the views of their constituents might decide against running for office. Financing a campaign is one of the most effective barriers to entry for candidates, as incumbents often raise huge “war chests” of money to ward off challengers. Across all US states in the 2014 state legislative elections, 91% of incumbents were reelected, and candidates without a monetary and incumbency advantage were elected only 10% of the time (Casey Reference Casey2016). Some scholars and public officials argue the incumbent monetary advantage and the high barrier to entry that exists for political fundraising can be remedied by the use of public financing. In this article, I investigate that claim in the context of all American state legislatures between 1976 and 2018. Does public financing enhance electoral competition in practice?

Public financing, in theory, should allow more challengers into elections due to the availability of campaign funds that do not have to be raised by the candidates themselves. These funds are openly available for all candidates to use, should they choose to accept them. Public funding means challengers do not have to spend the time and energy required to raise the amounts of money necessary for political success, and also gives challengers hope in beating incumbents due to the financial resources available for them. This logic yields the hypothesis that, because the availability of public funds allows for a relatively even financial playing field for candidates, public funding leads to greater electoral competition.

Between 1976 and 2018, multiple states implemented (and, in some cases, defunded) programs for public financing of candidates running for state legislative office. Using panel data, I employ multiple empirical strategies to estimate the effect of public financing on the number of candidates running for office. Analyzing the impact of public financing with data from all state legislatures over a long time period can shed light on how public financing may affect electoral competition across similar contexts.

In analyzing the effect of public financing across all state legislatures, I find that public financing projects over time have a positive effect on the total number of candidates running for state legislature, especially in the elections where greater amounts of public funds are available to candidates. Specifically, I find that switching to publicly financed elections corresponds with a greater number of candidates running for office. In addition, this positive result continues in the years after implementation of a public financing program. Thus, I conclude that public financing has a meaningful positive effect on increasing electoral competition.

Public Financing in the United States

Campaign finance reform dates back to the early 20th century with progressives proposing the use of public money to finance campaigns. It was Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 who recommended banning corporate political contributions to presidential campaigns, stating that Congress should provide funds for party expenses (Pickert Reference Pickert2008). Since this time, many states and cities have adopted some type of public funding system for elections, with Minnesota being the first to enact full public funding across all state elections in 1974. With full public funding, the government gives money to candidates to pay for nearly all campaign expenses; however, candidates must agree to not accept any private campaign contributions beyond a certain amount. Partial funding allows for the government to provide money to candidates for some campaign expenses, usually on a matching basis, and may have a provisional ban on some contributions, like those of political action committees (PACs) (Public Citizen 2012). The method of accessing money for publicly funding elections varies, with money coming from tax checkoffs, deductible contributions, or direct subsidies for candidates (Kulesza, Miller, and Witko Reference Kulesza, Miller and Witko2017).

Public financing of elections is a highly popular policy across the country, as citizens perceive public financing to improve integrity and rid government of the waste and corruption of private donations. The public financing proposals of Maine Question 3 in 1996 and Arizona Proposition 200 in 1998 each passed as referenda with a margin of victory in the tens of thousands (Malhotra Reference Malhotra2008). In Maine, the majority of legislative candidates and elected legislators continue to participate in the Maine Clean Elections program, and, seeing that participation in the program was declining over time, voters approved a citizen initiative in November 2015 to strengthen the program and make more money available to candidates.Footnote 1

Not only is there widespread support for publicly financed elections, but those which are implemented consistently have high levels of participation. Forty years after Minnesota enacted their program in 1974, 88% of eligible candidates opted into the state’s public financing system (Noble Reference Noble2017). In New Jersey, which utilized public financing for a subset of its elections in 2005 and 2007, constituents, members of the Assembly, and interest groups called for the expansion and increased accessibility of public funding in New Jersey even after the relatively unsuccessful first iteration of the project (The Office of Legislative Services 2005). Despite legal roadblocks presented by court cases which have overturned pieces of campaign finance regulation, many states continue to publicly finance legislative, gubernatorial, and judicial candidates.

Figure 1 displays the use of public funding by state legislative candidates in Connecticut between 2008, the program’s first year on the books, and 2020, the most recent election for which data are available. In the state, where public financing was passed by a Republican governor after the resignation of the previous governor due to campaign corruption,Footnote 2 80% of citizens favored Clean Elections, and 75% of successful candidates opted into the program in 2008, its very first year on the books; today, almost 85% of Connecticut state legislative candidates utilize public funds for their campaigns and 99% of all campaign contributions come from individual citizens (Noble Reference Noble2017; SEEC 2022a). 2010 had the lowest amount of participation since the program’s inception in 2008, with 71.4% of all candidates opting into public funds, and between 2016 and 2020, the program has seen a continued increase in candidate usage.

Figure 1. Percentage of Connecticut state legislative candidates utilizing public funds, 2008–2020.

There exists some anecdotal evidence of candidates who felt empowered to run for office with the availability of public financing (Phaneuf Reference Phaneuf2020; Rotman and Nightingale Reference Rotman and Nightingale2020). Although Connecticut’s Citizens’ Election Program was passed in response to corruption, public financing in the state has supported many candidates who otherwise would not have run for office. For example, Senator Mae Flexor has utilized public financing in each of her elections and attributed the viability of her campaigns to the program: “I ran because there were not a lot of young women in the legislature. I was not connected to wealthy people or lobbyists, so the Citizens’ Election Program made my run possible” (Phaneuf Reference Phaneuf2020; Rotman and Nightingale Reference Rotman and Nightingale2020). The ability of public financing to influence women to run for office is crucial, as candidates who identify with a group that has historically been excluded from politics are less likely to consider a run for office; public financing may assuage some of these concerns (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2005).

Other legislators in Connecticut have echoed the sentiments of Senator Flexor, as former Senate Minority Leader John McKinney saw that a major benefit of Clean Elections “was the ability to attract more people to run for office,” and particularly helped recruit Republican candidates in districts historically dominated by Democrats. Minor party candidates have expressed similar thoughts, including Connecticut Green Party candidate Mirna Martinez, who believed her strong campaign would not have been possible without Clean Elections funds (Rotman and Nightingale Reference Rotman and Nightingale2020).

There is a great deal of scholarly evidence on the benefits of public funds. Accepting public funding means spending less time raising money and more time lawmaking (Mayer, Werner, and Williams Reference Mayer, Werner and Williams2006). It also reduces overall levels of election spending due to provisions of spending limits, which prevent candidates from continuously attempting to out-fundraise each other, causing campaign spending to spiral out of control (Mayer and Wood Reference Mayer and Wood1995; Mayer, Werner, and Williams Reference Mayer, Werner and Williams2006). Additionally, large war chests amassed by incumbents are often found to negatively impact challenger emergence in state legislative campaigns. This phenomenon is weakened by public financing, which allows candidates to enter races without massive campaign accounts (Hogan Reference Hogan2001).

Soliciting many small donations for public funding not only removes big donors from a candidate’s fundraising calculus but also compels candidates to interact with a greater number of their constituents (Lee, Clark, and Vayas Reference Lee, Clark and Vayas2020). Publicly funded legislators are more likely to engage with and be responsive to a more diverse portion of their constituency (Miller Reference Miller2014; Noble Reference Noble2017). For example, New York City’s program for city council elections saw a donor pool that was racially and financially representative of city residents (Lee, Clark, and Vayas Reference Lee, Clark and Vayas2020). In turn, increased interactions with candidates due to public financing also positively impact voter knowledge and turnout, both in the given election and in future elections (Miller Reference Miller2014). Increasing policy responsiveness on the government side and political engagement on the constituent side are two major factors in enhancing democracy and accountability, both of which public funding can positively impact.

However, campaign finance reform has not always led to a noteworthy positive effect on electoral and legislative processes. Restrictions do not consistently lead to a more efficacious population of voters, and a decreased dependence on private funding does not necessarily lower legislative polarization (Harden and Kirkland Reference Harden and Kirkland2016; Primo and Milyo Reference Primo and Milyo2006). In places where campaign finance reform has attempted to stem the corrupting flow of large contributions, wealthy and highly partisan individuals and groups tend to dominate the financing of campaigns. Because spending more money increases candidates’ likelihood of winning, candidates often take extreme ideological positions in order to attract donors (Kilborn and Vishwanath Reference Kilborn and Vishwanath2021; La Raja and Schaffner Reference La Raja and Schaffner2015; Meirowitz Reference Meirowitz2008). Campaign finance reform also has the potential to create difficulties for nonincumbents because reforms can limit access to money that is necessary to make citizens aware of their candidacies and policy ideas, while regulation has also been found to lower the barrier to entry for nonincumbents (Jacobson Reference Jacobson1976).

Campaign Finance Reform and Electoral Competition

Campaign finance reform can sometimes actually have negative consequences for nonincumbents or potential candidates. Lott (Reference Lott2006) finds that, in states with contribution limits, state senate elections actually see fewer candidates seeking election, lower competitiveness in elections with larger margins of victory, and a higher chance of incumbents winning reelection. Nonincumbents need to cast a wider net rather than depend on a few wealthy donors, which requires more visibility that an incumbent may have but a challenger likely does not. Contribution limits hinder the ability of challengers to reach a wide audience by restricting their fundraising capabilities. High spending limits alongside public financing have been found to have negative electoral effects in gubernatorial elections because, despite reform, incumbents are still able to spend large sums of money that challengers may not have the ability to raise (Gross, Goidel, and Shields Reference Gross, Goidel and Shields2002). Overall, many suggestions for campaign finance reform would actually create difficulties for new candidates because reforms can limit access to money that is necessary to make citizens aware of their candidacies and policy ideas; these issues may contribute to the finding that public financing has not increased the number of challengers to incumbents in primary elections (Hamm and Hogan Reference Hamm and Hogan2008).

However, a major barrier to running for office is that many candidates cannot spend their own money and may not have the same recognition or financing in place as incumbents do. In states with public financing, more candidates tend to enter races, and incumbents are challenged more often, which increases opportunities to run for office and enhances voter choice (Malhotra Reference Malhotra2008). In particular, lower contribution limits to campaigns have been found to increase the probability of a challenger running against an incumbent in general elections for parties at all levels. Lower contribution limits tend to bolster challengers because more stringent limits on incumbents allow challengers a better perceived chance of winning, and thus lead to a higher likelihood of running (Hamm and Hogan Reference Hamm and Hogan2008). This phenomenon applies to public financing as well, because public financing has also been shown to decrease the number of uncontested seats and slightly reduce the incumbency advantage as it helps challengers to mount more effective campaigns (Malhotra Reference Malhotra2008).Footnote 3

There are multiple factors influencing the number of candidates running for office, with one of the most critical being access to financing a campaign. It is clear that there is a significant amount of evidence analyzing the link between campaign finance laws and electoral competition; however, the existing research has a number of shortcomings. Much of the research includes data before Arizona and Maine had the ability to strengthen and expand their programs, and before Connecticut even implemented Clean Elections. It also excludes the data of most other states. The time periods studied are short with only a few elections analyzed, and many include only the elections of one legislative chamber. Existing answers to the question of whether public financing impacts electoral competition are specific to time and place, and I attempt to remedy this specificity by analyzing all states across a longer time period to gain an understanding of the large-scale effects of public financing.

Public Financing and Increased Electoral Competition

While I anticipate that public financing increases the number of candidates entering elections by supplying them with funds, previous research linking campaign finance reform to electoral competition is conflicted and largely does not include data post-2008. Malhotra (Reference Malhotra2008) found that full public financing in Arizona and Maine increased electoral competitiveness; however, Mayer and Wood (Reference Mayer and Wood1995) established that partial public financing offered in Wisconsin did not encourage challengers to enter state legislative races and did not boost the competitiveness of contested races. Although there was a modest increase in competitiveness due to fewer uncontested incumbents, there has been no notable long-term change in incumbent reelection rates or margins of victory (Mayer Reference Mayer2013). Some research finds that campaign finance reform can actually have negative consequences for nonincumbents or potential candidates, while others find that public financing increases hope and confidence in challengers by making their campaigns more viable (Lott Reference Lott2006; Mayer and Wood Reference Mayer and Wood1995; Mayer, Werner, and Williams Reference Mayer, Werner and Williams2006).

Public financing, in theory, should allow more candidates into elections due to the availability of campaign funds that do not have to be raised by the candidates themselves. In particular, I expect to find a change in the number of state legislative candidates over time after the introduction of public financing. Because public financing is available to all candidates, should they reach the threshold of small donations and choose to accept the funds, public funding should result in an increase in the number of candidates across districts, and therefore at the state level across states.Footnote 4 Public funding means candidates do not have to spend the time and energy required to raise huge sums of money and also makes the campaigns of challengers more viable by evening the financial playing field with incumbents, which instills more confidence in a challenger who may be opposing a current legislator with those resources already available to them.

H1: Implementation of public financing corresponds with an increase in the number of general election candidates compared with states that privately finance elections.

This hypothesis reflects the assumption that offering funds to candidates that they do not have to raise themselves, but are instead offered by the government, should enhance opportunities to run for office. Fewer obstacles hindering candidacy should mean more candidates in elections. I expect to find that, in elections with public financing, races see a higher number of candidates.

In addition, I expect to find a positive year-over-year cumulative treatment of public financing on electoral competition. Not only do I expect more candidates to enter publicly financed races, but also that the number of candidates entering races due to the availability of public financing continues to increase every election after the introduction of the program. I expect to find this “snowball” effect because each election cycle makes citizens and candidates more aware of the availability of public funding through governmental advertising and education, as well as through candidates who are required to interact with and solicit donations from a wide swath of their constituency (Miller Reference Miller2014). Potential candidates may also gain awareness through ballot initiatives to expand access and availability of public funds, like that of Maine, where voters approved a citizen initiative in November 2015 to strengthen their Clean Elections program and make more public money available to candidates (Burke Reference Burke2019).

H2: In each successive year after the introduction of public financing, more candidates enter publicly financed races compared with states that privately finance elections.

Of course, the null hypothesis—that public financing exerts no effect on candidates for state legislative office—is also plausible. However, in order to find no effect, several possibilities would need to hold true. For one, financing a campaign may not be part of a candidate’s major calculus of whether or not to enter a race. Should a candidate not be concerned about fundraising, they are unlikely to be swayed to run for office by the option to have the government fund their campaign. On the other hand, a potential candidate may perceive the amount of money offered by the government to be too low an amount to justify running, or that the requirements to qualify for public funding are too strenuous to meet. Should a state have low levels of citizen knowledge about public financing, then potential candidates may not even know it is an option and therefore not experience a difference in likelihood of running for office. An alternate possibility is that, while public financing may present one less obstacle to running for office, other barriers may take precedence in the mind of a candidate. For example, a potential candidate belonging to a group that has been historically underrepresented in government may view their minority status as a greater obstacle to running for office than financing a campaign (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2005).

Research Design

A number of states have implemented public financing programs to fund state legislative campaigns over time. In total, eight states in the US have offered public funding for state legislative office in the time period between 1976 and 2018: Arizona, Connecticut, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Wisconsin.Footnote 5 Figure 2 illustrates how public financing has changed across states between 1976 (two years after Minnesota’s legislature passed a public financing bill) and 2018. States that have repealed their public financing programs appear grey in the map-year after the program was repealed; all other states which utilize public financing in the map-year displayed appear black.

Figure 2. The maps present states that have utilized legislative public financing between 1976 and 2018. Black states indicate the utilization of public financing. Grey states indicate repealed public financing projects.

This article utilizes a time series cross-sectional analysis of recent data to fill this gap in scholarly understanding of the effect of public financing on electoral competition. An analysis of all state legislative races over a longer period of time allows for a generalized assessment of the impacts of public financing across all US legislatures. Additionally, with data as recent as 2018, exploring the impacts of taxpayer funded elections across states over time provides a current picture of the relationship between public financing and electoral competition in today’s political climate. The number of candidates running for office is a good test of the electoral impact of public financing because increasing access to money for campaigns, and therefore eliminating a major source of hesitation to entering a race, should open the door for more candidates to run.

Analysis of the broader relationship between public financing and electoral competition across US state legislatures follows a similar design to that of Harden and Kirkland (Reference Harden and Kirkland2016), where the authors analyze the effect of public financing on legislative polarization. The data on the number of candidates running for general election in each state-year come from Klarner (Reference Klarner2021) and Ballotpedia.org. The years in which states utilize public financing also come from Ballotpedia.org.

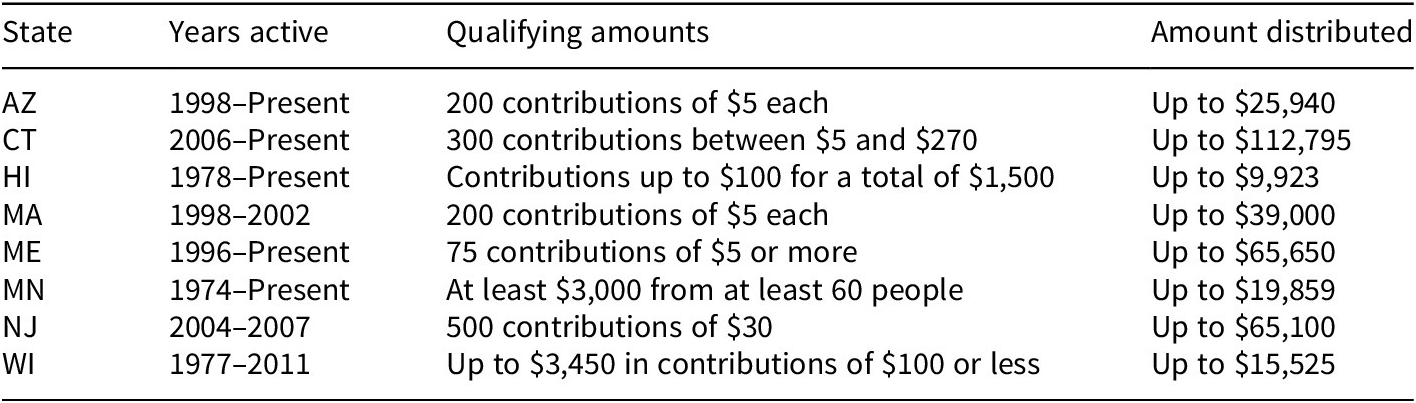

There are a variety of ways to publicly finance state legislative elections. States can differ in terms of the years in which the policy is utilized, the qualifying amounts for candidates, and the amount of public funds distributed. Table 1 lays out the different ways in which states utilize public financing in their legislative elections.

Table 1. Public financing methods.

I am able to take advantage of institutional variation in campaign finance regulation across state-years and compare states with and without public financing between 1976 and 2018 to determine whether public financing has a meaningful positive effect in increasing the total number of candidates running for office. Because of the length of time for which data are available and the fact that states have both implemented and repealed programs throughout this period of time, I am able to compare candidate counts within a state in years it did and did not have public financing, as well as among different states with and without public financing.

Additionally, with data from as recently as 2018, exploring the impacts of taxpayer funded elections across states throughout time provides a current picture of the relationship between public financing and electoral competition in today’s political climate. The temporal data and staggered adoptions of public financing allow for fairly strong analytic leverage, at least in the context of observational data.

Electoral Competition

The number of candidates running in state legislative elections serves as an important measure of electoral competition for a number of reasons. For one, a healthy democracy does not shut citizens out from candidacy simply due to the high financial cost. It is not beneficial for a democracy to have such a high bar to run for office so as to be unattainable for the vast majority of the population, leaving legislation to be controlled by the wealthy. Analyzing the number of candidacies for legislative seats provides evidence as to whether public financing has barrier-lowering effects on running for office, because public funds may make running for office available to those who would otherwise see a campaign as financially infeasible.

Increasing the number of options for voters to choose from may boost feelings of satisfaction and confidence in government. Competitive elections are indicative of a healthy democracy; more competitive elections result in greater mobilizing and advertising efforts, which leads to more citizen knowledge and increased turnout (McDonald Reference McDonald2006). The number of candidates running for office also serves as a prospective measure of competition, as opposed to a retrospective measure like vote share, which occurs after the end of a campaign. The primary outcome of interest in this article is whether public financing lowers the barrier to running for office, and lowering the barrier to office should result in more candidates running.

In state politics, incumbents have a huge advantage in gaining reelection, which often shuts out potential candidates. Less than a third of state legislatures have term limits, which means most states allow consistent reelection campaigns of incumbents until they choose to retire (Ballotpedia 2021). Much of the incumbent advantage is financial, as candidates who have been elected and have prior experience do not need to put the same level of effort into fundraising and campaigning as a relatively unknown challenger (OpenSecrets 2021). Although campaign laws are designated to prevent fraud by current officeholders, incumbents also have significant resources at their disposal in reelection efforts. For example, while legislative staff cannot campaign during work hours, they often moonlight on their legislator’s campaign (National Conference of State Legislatures 2021a). Access to volunteers is a major factor in a campaign, and incumbents often already have a built-in volunteer force. Strong incumbents also face lower caliber challengers, likely because potential candidates are deterred from facing entrenched legislators with a significant war chest of funds (Gowrisankaran Reference Gowrisankaran2004). Studying phenomena that lower the financial barrier to entry for elections, while still requiring significant demonstrated support at the district level, may result in a greater number of challengers to incumbents and potentially improve the quality of candidates.

Even when candidates lose, elected officials often incorporate issues brought forth by their challengers into their agenda while in office, a phenomenon known as “issue uptake” (Sulkin Reference Sulkin2005). While the entrance of some candidates to the political arena may not be successful in terms of winning elections, their concerns often continue to be reflected in politics after the end of their campaign. If a larger number of candidates run for office, the candidate field is likely to have a more diverse set of ideologies and policy preferences, which would yield greater issue uptake for the future elected officeholder. A “safe” election in which a longstanding officeholder is reelected with little challenge does not have the same issue uptake impact as an election with a large and ideologically diverse field of candidates. Therefore, the emergence of additional candidates is relevant notwithstanding the electoral outcome, as their platforms may impact policy regardless of whether the candidate wins or loses.

Two-Way Fixed Effects

My analysis includes the number of candidates running for all seats in the 99 state legislative bodies from 1976 to 2018 in states with and without public financing. The data come from a panel dataset, where multiple observations (in this case, legislative candidates) are repeated over time. I use temporal variation to estimate the link between public financing and competitiveness of elections.

I model the data with two-way fixed effects regressions. These models include state and year fixed effects. State fixed effects remove time-invariant characteristics of states, and year fixed effects remove any baseline temporal trends in the number of challengers in order to isolate the effect of public financing on challengers in a given election.Footnote 6 The treatment variable denotes a state-year in which public financing was available to candidates running for office; units are untreated if the state did not offer public financing in state legislative elections in a given year.

With state-year data, I am able to leverage the institutional variation in campaign finance regulations across states and years to determine the impact of public financing on electoral competition. The two-way fixed effects method allows for the analysis of differences across states, as well as within publicly financed states over time. As previously discussed, some states only recently implemented public financing; analyzing data at the state-year level means that I can estimate the candidate difference between, for example, Connecticut and nonpublicly financed states, as well as the difference in candidates before and after Connecticut’s implementation of public financing. The state-year level is also the best level at which to conduct this research due to availability of data. There exists very little data at the individual-race level, and that which does is extremely limited due to the difficulty of collecting data on each individual candidate who accepts public funding; therefore, the state-year level provides the best unit of analysis, both in terms of availability and methodology.Footnote 7

I include a number of time-varying covariates to control for any confounding that is not accounted for by the state and year fixed effects. States vary widely in the number of seats they offer for election in each chamber; for example, when Alaska’s Senate holds 20 seats up for election, New Hampshire’s House simultaneously reelects its 400 state representatives. Since the chamber and number of seats up for election have an effect on the number of candidates running for office, I control for state totals of House and Senate seats, as well as the chamber in which the election occurs (Cox Reference Cox1997).

I expect a number of other covariates to also have an effect on whether public financing increases the number of candidates in a given legislative race. Since term limits have been found to increase legislative turnover, it is possible that more frequent open seats lead to a larger number of candidates vying for election (Apollonio and La Raja Reference Apollonio and La Raja2006). Additionally, as public financing of elections is a both progressive and expensive policy, states whose governments lean liberal and have deeper pockets may be more likely to implement public financing. I include measures of state government ideology and state expenditures to account for differences in governing priorities and resources across states (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and Hanson1998). I also include a folded Ranney index to measure state government party competition, as well as Bowen and Greene (Reference Bowen and Greene2014)’s two measures of professionalism, as I expect more competitive chambers yield more competitive elections. Finally, since seats in more professionalized chambers are highly valued, I expect those elections to be more competitive than less professionalized chambers (Squire Reference Squire2007).

Because findings on whether public financing exerts a positive effect on electoral competition are conflicting, in addition to the 1976–2018 analysis, I also attempt to understand the null results of previous studies by modeling different time periods and different levels of public financing with two-way fixed effects regressions. The purpose of these sections is to determine whether there is a differentiated impact of public financing when greater amounts of funds are offered and to understand previous null results by examining public financing in a number of isolated time periods.

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting

An assumption of the two-way fixed effects estimator is that the decision of legislatures to enact public financing laws is unrelated to whether those laws will increase the number of candidates entering races. While the passage of campaign finance regulation is often related to fraud, it is feasible that legislators who support the passage of their state’s law also believe public funds may increase access to running an election, which could potentially impact the outcome. Therefore, the passage of a public financing policy may correlate with a legislature’s desire to increase the number of candidates entering legislative elections, as well as the resulting number of candidates entering elections after the passage of the policy.

Due to the potential bias that selection into treatment creates, I also utilize Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) to model the passage of public financing laws (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2013). Through IPTW, I calculate a series of weights to balance treated and untreated observations.Footnote 8 These weights separate the decision to implement public financing from the number of candidates running for state legislative office. To estimate the weights, I model whether a state legislature employed the use of public financing in a given year as a function of several groups of covariates in a logistic regression. The weights are derived from the inverse of the fitted probability of adopting public financing in a given year. State and year fixed effects account for the probability of implementing public financing.

After generating the weights, I again utilize two-way fixed effects to calculate the effect of treatment, conceptualized in two ways with the contemporaneous effect of treatment (CET) and the cumulative average treatment history effect (ATHE). The CET is the effect of switching a state from private to public financing in period t, averaging over whether the state has utilized public financing prior to t (Blackwell and Glynn Reference Blackwell and Glynn2018). The cumulative ATHE accounts for a state’s full treatment history, which Ladam, Harden, and Windett (Reference Ladam, Harden and Windett2018) conceptualize as the “legacy effect” of treatment. The ATHE is the average difference between the world where all states utilized private financing in every time period up to time t, and the world where all states utilized public financing in every time period up to time t (Blackwell and Glynn Reference Blackwell and Glynn2018).

These two methods capture different aspects of the influence of public financing: the CET indicates the causal effect of public financing in a single election year, while the cumulative ATHE comes from a measure of the total number of election cycles in which a state utilizes public financing. The cumulative ATHE allows for an understanding of the impact of public financing on electoral competition outside of the current time period, as it indicates the change in number of candidates running for office after each additional year of public financing.

Results

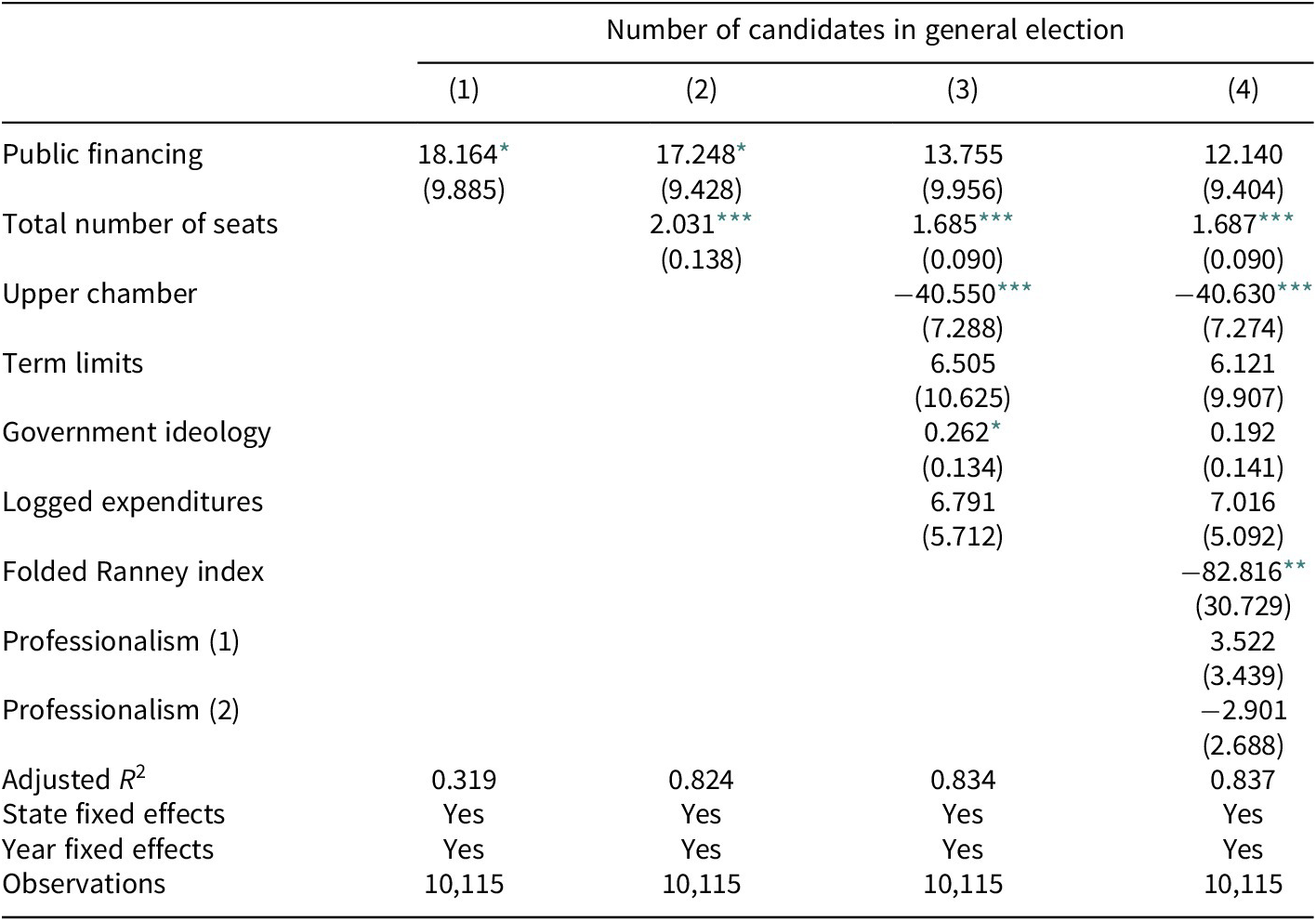

Table 2 reports the two-way fixed effects estimation of public financing on the total number of candidates running for state legislature.Footnote 9 Standard errors are clustered by state and year. The coefficient on the treatment variable, “Public Financing,” measures the extent to which public funds affected the total number of candidates running for office for a within-state change from private to public funding.

Table 2. Two-way fixed effects model of effect of public financing on candidate totals in all state legislatures, 1976–2018.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

Across all state legislatures, those state-years with public financing saw an increase in the number of candidates running for office by between 12 and 18 candidates. An increase of 12–18 candidates corresponds to approximately 9%–14% of a standard deviation of the dependent variable, number of candidates.Footnote 10 While a full standard deviation change would suggest moving from private to public financing would increase a state’s candidate pool by an additional 131 candidates, 9%–14% of the standard deviation is a noteworthy value. This finding provides suggestive evidence that public financing increases the number of candidates running for state legislative office and lends support to the hypothesis that public financing bolsters more candidates to enter races.Footnote 11

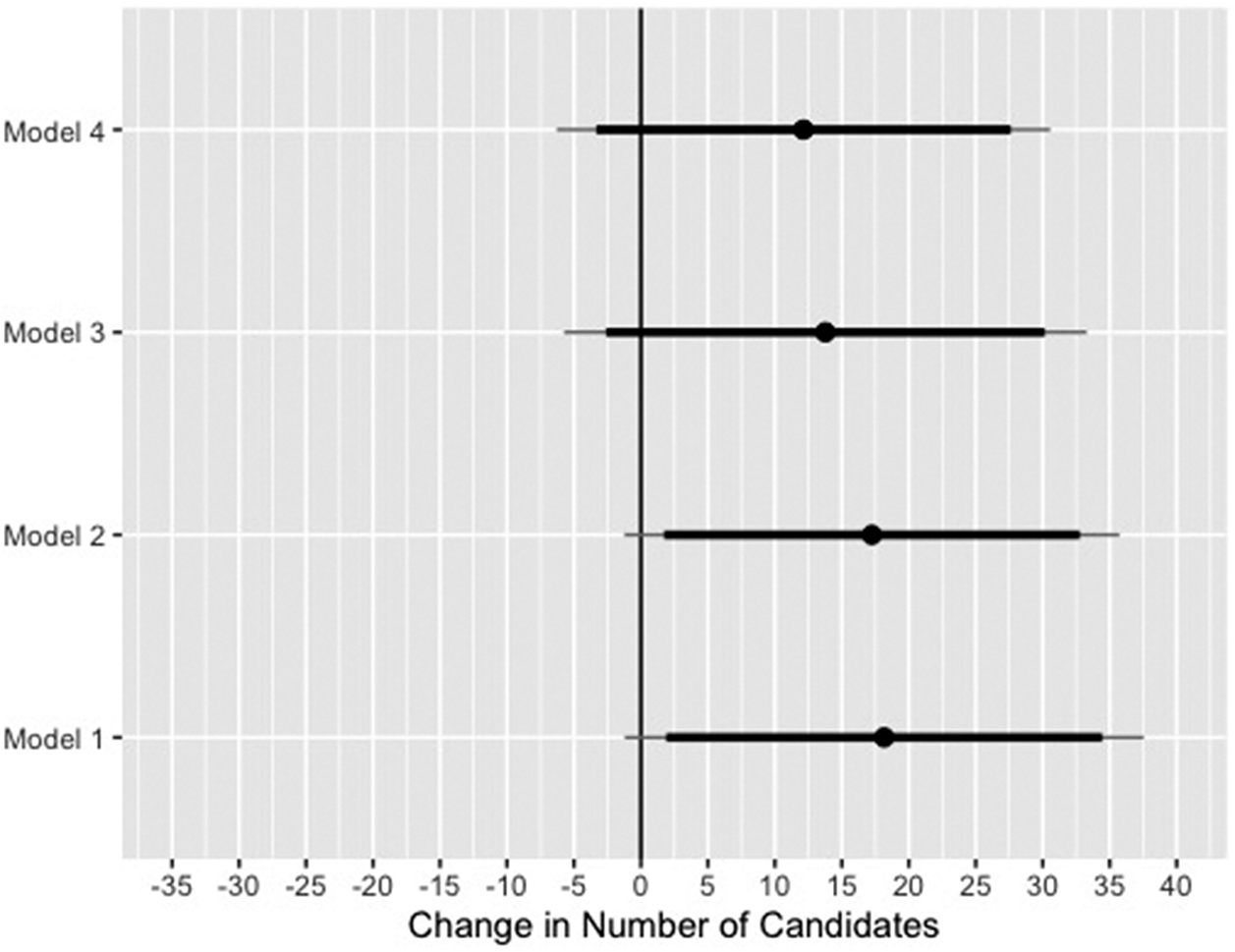

As depicted in Figure 3, the standard errors of the estimates are sizable and only the estimates of the first two models are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level; the treatment coefficients on Models 3 and 4 do not reach statistical significance at the conventional level. As discussed above, between 1976 and 2018, eight states in the US have offered public funds for state legislative office; additionally, these states did not utilize public financing throughout the entire time period. The power of the analysis is weakened by the small sample size of publicly financed elections, resulting in large standard errors and greater uncertainty in the estimate. As such, the interpretation of these results merits appropriate caution. However, the magnitude of the four model estimates is positive and large.

Figure 3. Effect of public financing on electoral competition over time with 90% confidence intervals in black and 95% confidence intervals in grey.

A larger and more representative candidate field can increase the trust and satisfaction of constituents, as they see the political process as more accessible to the average citizen, rather than restricted to only those with connections to the wealth necessary to run a privately financed campaign. Constituents in publicly financed states with large and ideologically diverse candidate pools may have more positive feelings toward democratic elections overall. An increase in candidates may also result in candidates promoting different spheres of representational preferences aside from policy representation, including demographic diversity among candidates (see Griffin and Flavin Reference Griffin and Flavin2011; Harden Reference Harden2016).

Publicly financed campaigns also have the impact of interacting more with their constituencies, which results in greater political knowledge, and therefore greater turnout (see Miller Reference Miller2014). Additional candidates either have the ability to incorporate their new ideas during their term in office or are likely to influence the agenda of their opponents; therefore, regardless of the electoral outcome, these candidacies could have a major impact on policy (Sulkin Reference Sulkin2005).

Two-Way Fixed Effects with IPTW

Figure 4 illustrates treatment effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the total treatment estimate and cumulative treatment estimate. The total treatment estimate is the two-way fixed effects result of how public financing impacts the number of candidates running for office for a change from private to public funding with the reweighted data to reduce bias. The cumulative treatment estimate indicates how many additional candidates run in state legislative elections for each successive year after the introduction of public financing.Footnote 12

Figure 4. IPTW results with 95% confidence intervals.

The first result is the CET estimate. Across all state legislatures, a switch from privately funded elections to public financing corresponds with about an 18 candidate increase in a given election year; the rebalanced data indicate a similar increase in competition compared to the unweighted two-way fixed effects results. The standard errors are again sizable, but the estimate remains positive and large and therefore supports the hypothesis that public financing increases electoral competition.

Moving to the figure on the right, the cumulative ATHE results indicate that publicly financed elections see an increase of about two candidates for each additional year after the implementation of public financing, compared to those states with privately financed elections. Because the ATHE treatment is a count variable, the ATHE estimate has additional power compared to the CET estimate, resulting in smaller confidence intervals and significance at the 0.05 level. This finding supports the hypothesis that public financing continues to increase electoral competition for every year after the policy is put in place.

Public Financing Through the Years

As previously mentioned, much of the findings on public financing’s impact on electoral competition are conflicting, or authors suggest the need to interpret results with caution (see Lott Reference Lott2006). While I suggest some caution in interpretation of the two-way fixed effects results due to large standard errors, my analysis suggests that public financing has a positive and large effect on electoral competition over time, which motivates the question of how my analysis differs from that which came before. My research paints a holistic picture of public financing by including both chambers in all state legislatures between 1976 and 2018; however, taking a more granular look at how public financing may have impacted electoral competition differently throughout time may provide some information on how it functions. In this section, I evaluate how public financing may have changed over time.

Figure 5 illustrates the two-way fixed effects results of a number of different time periods in which public financing was available in multiple state legislatures. All years are both statistically insignificant and substantively smaller than the effect between 1976 and 2018, with a small negative effect in the years 2000–2018. However, the estimates are still positive and reasonably large in the earlier years, and the reduced power of the analysis can be attributed to the inclusion of fewer treated state-years in each time period subset.

Figure 5. Effect of public financing on electoral competition in different time periods with 90% confidence intervals in black and 95% confidence intervals in grey.

Substantively, the difference in estimates over time may be attributed to long-term shifts in campaign funding, both within publicly financed legislatures and across states. In the cases of Massachusetts and New Jersey, legislative elections were publicly financed for less than six years. These legislatures did not have the ability to adapt and expand the law to match the requirements of the state, as citizens in Maine did in 2015, when voters approved an additional initiative to strengthen the public funding program and make more money available to candidates (Burke Reference Burke2019). Although Wisconsin began publicly funding its elections in 1977, Wisconsin Act 370 in 1987 repealed the provision which increased public funds at the rate of inflation, thus fixing grant amounts at 1987 levels. In subsequent years, the grant received little funding and low levels of participation, until Governor Scott Walker effectively ended Wisconsin’s public financing program 33 years after its implementation (Leuders Reference Leuders2011). The slight negative effect between 2000 and 2018 may be at least partially attributable to these three states, each of which had public financing in name but invested less effort and funds in their programs over time. Poorly executed programs may not have a positive impact on electoral outcomes, as there is little incentive or ability to utilize public funds.

While state candidates have historically depended on donations to successfully run their campaigns and stay in office, fundraising requirements have only increased as the cost of elections has spiraled out of control. In the 2020 elections, the average Democratic candidate in the Texas State Legislature raised $119,046.00, while the average Republican raised an even greater amount of $152,953.00, a sum which is almost five times the US median income (Ballotpedia 2020a). In California, the amount of itemized contributions in 2020 state elections totaled $1,671,408,159.00 (OpenSecrets 2020). Regardless of whether the option to publicly finance a state campaign exists, many candidates may be dissuaded from running for office simply due to the perception of ever-increasing modern election costs.

The results above indicate a generally consistent, but statistically insignificant, pattern of more candidates running under public financing, with the strongest effects occurring in the first half of the time period. These findings provide suggestive evidence that public financing increases electoral competition regardless of the time period, but the most powerful and generalizable way to estimate the effects of public financing is over the course of many elections.

Differentiating Types of Public Financing

In this section, I evaluate how offering a greater amount of public funds impacts candidate totals. As noted in Table 1, states offer varying amounts of public funds to candidates running for state legislative office. The amounts of public funds offered across states range from up to $9,923.00 in Hawaii to up to $112,795.00 in Connecticut Senate races; in addition, the amount of funds candidates accept often varies, as they do not always reach the maximum amount offered. Because there is so much variation in amount of funds offered and accepted across and within states, I create four distinct levels of legislative public funding, where each additional level denotes an increase in the amount of campaign expenses covered by public funding. Table 3 illustrates the categories for amounts of funding and the states to which those categories apply.

Table 3. Levels of public financing.

Table 4 illustrates the two-way fixed effects results with a public financing variable that differentiates the amount of funds offered to candidates. During the years in which a state publicly funded their legislative elections, increasing the amount of expenses covered by public financing corresponds with an increase in 6–9 candidates for state legislature. Public financing has a statistically and substantively significant impact on the number of candidates running for office in each model. These results provide strong support for the hypothesis that increasing the amount of public funds offered to candidates corresponds with greater electoral competition.

Table 4. Two-way fixed effects model of effect of differentiated levels of public financing on candidate totals in all state legislatures, 1976–2018.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

In states where legislative candidates are offered greater amounts of money for elections, more candidates run for office. As mentioned previously, the cost of running for office has increased exponentially, which may dissuade potential candidates. The finding that more public funds increase electoral competition may be attributed to two potential causes. First, the infrastructure of public financing in states that offer greater funds is more advanced, and so those states may have a better system set up to educate potential candidates on the benefits and use of public funds. Second, candidates may be more likely to run for office when almost all of their campaign costs are covered, rather than only a portion. Partial public financing programs require personally raising more money and receiving fewer public funds. While partial public funding does lower the barrier to entry compared to fundraising all campaign costs, it still requires a more significant amount of effort than full public funding.Footnote 13

The Future of Public Financing

The results of tests analyzing data from all US state legislatures between 1976 and 2018 suggest that public financing increases the number of candidates running in state legislative elections and continues to support new candidacies for every election after the implementation of the policy. The two-way fixed effects finding that public financing increases the number of candidates running for office should be interpreted with some caution due to a lack of conventional statistical significance in two of the four models.

However, the two-way fixed effects model linking greater amounts of public funds to more candidates achieved both statistical and substantive significance, and the statistically significant ATHE results indicate that two more candidates enter publicly financed elections for each additional year public funds are offered. The ATHE serves an advantageous estimand because it allows for additional power and smaller confidence bounds, and therefore is the most precise estimate of the effect of public financing on electoral competition. Public financing, once implemented, can continue to have positive impacts on elections many years after the policy is passed.

The results of more recent elections indicate that, as political campaigns become more expensive across the board and some public financing projects go underfunded, there are less consistent positive effects of public financing on electoral competition.Footnote 14 These findings leave room for the possibility that the barrier-lowering effects of public financing, in some cases, may not outweigh a candidate’s more notable considerations when running for office (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2005). However, states that offer greater amounts of public funds are more likely to see an increase in the number of candidates running for office. In addition, implementing public financing on a larger scale can roll back spiral campaign spending, and efforts to make potential candidates more aware of the accessibility of public financing and other available resources may improve the outlook of those who are generally concerned about the cost of running in an election (Mayer and Wood Reference Mayer and Wood1995; Mayer, Werner, and Williams Reference Mayer, Werner and Williams2006; The Office of Legislative Services, 2005).

Constituents continue to be largely supportive of public financing, as evidenced by Maine’s vote to increase the amount of funds offered to candidates by the state’s Clean Elections Program in 2015 (Malhotra Reference Malhotra2008). In fact, while the focus of this article is primarily on how public financing impacts candidates, constituents may actually be the primary beneficiaries of public financing. Among its Clean Elections Program goals, Connecticut cites “Restoring public confidence in the electoral and legislative processes,” and “Increasing meaningful citizen participation” (SEEC 2022b). On the electoral side, candidates in Minnesota, the country’s oldest public financing system, consistently opt into accepting spending limits and utilizing public funds year after year; more recent public financing programs have also seen persistently high levels of participation since their implementation (Noble Reference Noble2017).

Citizens and governments alike continue to demand clean elections through public financing, and there are a number of bills and citizen-organized committees in cities and states calling for reform today. In 2019, New York State passed a bill to publicly fund statewide and state legislative candidates. Other instances of support for public financing include the Illinois legislature proposing Clean Elections bills each session, as well as 2020 Democratic Presidential Candidate Kirsten Gillibrand’s Clean Elections Plan to give voters $200 vouchers to donate to presidential and congressional elections in order to “get big, unaccountable money out of politics” (Gillibrand Reference Gillibrand2019; National Conference of State Legislatures 2021b). Additionally, large cities across the US continue to sign public funding projects into law, with Seattle being the most recent to approve a program of “Democracy Dollars” (on which Gillibrand modeled her plan), where 2019 voucher payments to city council candidates totaled $2,454,475.00 (Seattle.gov 2020).

Conclusion

Many proponents of campaign finance reform state that private donations have negative effects on candidates and campaigns, with claims ranging from incumbents spending too much time raising campaign funds, which takes away from lawmaking, to donors gaining political influence through their contributions. Raising money for elections has changed significantly in recent years, and there has been increased scrutiny on the downstream impacts of large campaign contributions. Of particular importance to this article is a potential link between private donations and electoral competition. Proponents of financing political campaigns publicly argue that passing up private money in favor of nonpartisan taxpayer dollars to fund campaigns could have a positive impact on the number of candidates entering a race. This makes sense logically, as financing a campaign is a major barrier to entry for any citizen, and particularly to one who may want to challenge a popular incumbent that already has a significant war chest of funds.

What follows in practice supports the claim of public financing fostering more competitive elections. The results of this study suggest that the availability of public financing among all US state legislatures between 1976 and 2018 had a positive effect on the number of candidates running for office. The two-way fixed effects results indicated that states with public financing saw between 12 and 18 additional candidates running for legislative office after implementing a program. After reweighting the data to reduce bias, I found that public financing increases the field by over 18 candidates compared to states without the policy; while this estimate was not statistically significant, a value this large still has important substantive implications. The most statistically powerful estimate indicates that for every year the policy is in place, publicly financed elections increase the political playing field by two additional candidates.

States that offer greater amounts of public funds also tend to see a more significant increase in candidacies as opposed to states with smaller public funding grants. The findings of this analysis largely support my hypothesis that taxpayer-funded elections increase the number of competitors running for office and suggest that public funds should be extended to a greater number of aspiring state legislative candidates across the country in order to foster greater political competition. Substantively, these additional candidates would not run their campaign without public financing, which means public financing expands the political field and potentially results in greater representation of constituents’ views in elections.

These data support previous research that estimated a meaningful effect of public financing on electoral competition. However, this article takes a more holistic approach to analyzing the link between campaign finance and candidates entering races. While previous work excluded most states, focused only on a few elections, and was missing data from states that recently implemented public financing programs, this article leverages a panel data analysis of US state legislative races for all 99 chambers between 1976 and 2018. The scope of the data is extensive; however, the focus of the article is exclusively on public financing and its impact on electoral competition. Future research should explore the downstream effects of these findings; for example, considering female candidates are more likely than male candidates to express concerns about fundraising for a campaign (see Miller Reference Miller2014; Sanbonmatsu, Carroll, and Walsh Reference Sanbonmatsu, Carroll and Walsh2009; Hogan Reference Hogan2007), does an increase in candidates running for office due to public financing result in a more gender-diverse candidate pool?

As previously mentioned, meaningful competition is tremendously important in the political sphere. The conclusion drawn from this study is that public funding can encourage more candidates to run for office under the right conditions, and making widespread funding available to candidates, as well as states properly developing, implementing, and adapting programs, improves electoral competition. Not only is public financing successful in that citizens perceive the policy as cleansing corrupt politicians beholden to big donors, but it also lowers the barrier to entry and leads to greater access to political elections. With more candidates running for office, it is more likely for a greater range of ideological views to be represented by the multiple candidacies, resulting in voters having a larger field from which to choose the most representative candidate for them.Footnote 15 More candidates may also mean that incumbents are challenged more often, and entrenched politicians in seemingly “safe seats” cannot simply rest on their laurels. Voters who feel their beliefs are better reflected in a larger, more representative candidate field may in turn become more efficacious and feel greater satisfaction toward their government.

Increasing the competitiveness of elections through public funding also positively impacts voter turnout, as constituents interact more with their district’s candidates, are better informed, and are more likely to vote. Constituents who recognize the candidate pool is representative and elections are not exclusive to rich candidates may also feel greater trust and confidence in democratic elections, as they perceive that candidacy is not accessible only to those with connections to wealthy donors. Representative ballot options and citizen efficacy are two important elements of a successful democracy, both of which public financing can improve. Public funding can please citizens and increase representation by improving accessibility of running for public office, allowing for more candidates to enter elections.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2022.12.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available on the SPPQ Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/HQFBAY (Mancinelli Reference Mancinelli2022).

Funding Statement

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biography

Abigail Mancinelli is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Notre Dame in the Department of Political Science. Her primary research interests include representation, state politics, campaigns and elections, and campaign finance.