The outside skin is a marvellous plan

For extending the dregs of the flesh of man,

While the inner extracts from the food and the air

What is needed the waste of the flesh to repair.

Too much brandy, whiskey or gin

Is apt to disorder the skin within;

While, if dirty or dry, the skin without

Refuses to let the sweat come out.

Good people all! Have a care of your skin,

Both that without and that within.

To the first, give plenty of water and soap,

To the latter little else but water we hope.Footnote 1

In a time of continuous fear of death and disease, Alfred Power’s 1871 sanitary rhyme revealed a profound idea about the moral and reforming value of the skin. After thorough microscopical studies and the determination of the sweat ducts, in the early nineteenth-century skin has been redefined as an organ with complex physiological functioning. By the 1840s, physicians such as the London dermatologist Erasmus Wilson (1809–84) had started using this knowledge as a tool for sanitary reform. In the popular work Healthy Skin (1845), Wilson preached the message of skin cleanliness for the general public.Footnote 2 He believed that a moral uplifting of society could be achieved through cleansing and controlling the vital and all-influencing skin.Footnote 3 Publications such as Healthy Skin and other popular handbooks on health, beauty and household cleanliness connected a renewed appraisal for the skin system to the physical and moral cleanliness of workers, women and children. Moreover, Wilson’s messages ended up in one of the strongest visual campaigns for skin cleanliness in the late nineteenth century: the mass advertising campaign for Pears’ soap.

These popular writings on skin are significant for pointing to the role of the skin as a symbolic surface. Skin represented the organ of drainage for body and society. To keep the skin clean and purge it of waste materials such as sweat and dirt resonated in a Victorian Britain awash with improvements in city sanitation, novel female beauty practices, new views of racial identity and moral reform. Characterising skin as a ‘sanitary commissioner’Footnote 4 of the body, popular health publications revealed just how much the contemporary understanding of skin defined and connected concepts of cleanliness and the visual ideals of the healthy body in Victorian Britain.

This focus on skin and public health improves our understanding of the history of body care and bodily control in the sanitary context. So far medical historians have discussed meanings and experiences of skin in the context of particular periods and medical practices.Footnote 5 The excellent collection A Medical History of Skin contains recent contributions on skin diseases, stigma associated with them, and their visual representation.Footnote 6 Cultural historians, social anthropologists, and literary scholars have focused on the body and skin as a cultural subject shaped by history.Footnote 7 In her study Skin: On the Cultural Border between Self and the World (2002), literary historian Claudia Benthien shows how conceptualisations of coloured skin, skin as a boundary and skin as a mirror of the soul are moulded in history and culture. Although Benthien, and in a similar way Steven Connor in his inspiring The Book of Skin, demonstrate the cultural metaphor of skin in history, they do not fully analyse the practical understandings of skin in popular physiology or visual sources. How were women and men in Victorian Britain confronted with the value of skin hygiene in everyday life? How did the skin become morally charged in popular health? Erasmus Wilson’s work on skin and other handbooks on cleanliness together with visual motifs in soap advertisements transformed the skin from a receptive layer into a tool of control for health, beauty and civilisation.

Sanitary conceptions of skin, of which Erasmus Wilson’s ideas are a distinctive example, gained meaning when medical definition and popular (visual) imagination of the body intersected. A close study of popular writings on skin reveals fundamental analogies between the skin as the drainage system for the body and needs for proper city and domestic sewage and bathing facilities. Similarly, an analysis of common soap advertisements exposes the layered visual exposition of the skin as an organ of body and society, disclosing references to control over race, gender and personal beauty. For Victorian women and sanitarians alike, skin became the locus of control over unwanted ‘evacuations’ on all levels.

This article offers a history of skin through the lens of the sanitary movement by focusing on the popular work of Erasmus Wilson. His story of skin encompasses a decisive episode in the historiography of the medical history of the body, when developments in the struggle for control over healthy skin still in place today first began. Even in such broad genres of scholarship as the history of public health and cleanliness,Footnote 8 the skin has hardly been discussed as a separate topic. Virginia Smith in her encompassing study on the history of personal hygiene convincingly shows how care of the skin played an important part in vitalist physiology and calls for cleanliness from 1800 onwards.Footnote 9 Yet the importance of skin cleanliness and the skin’s ability to evacuate waste materials really gained currency after the anatomical definition of the sweat ducts and the popularisation of the anatomy of skin as a whole within the drainage-focused sanitary movement. The emergence of attention to skin diseases and the microscopical journey into the depths of skin structures in the first half of the century articulated the skin as an organ that mattered and one that symbolised the promise of control over disease. Moreover, this paper argues that Wilson’s popular writings on skin and bodily health, picked up by the producers of Pears’ soap, indicated how popular knowledge of the skin was imprinted in symbolic and morally loaded pictures.

Healthy Skin 1835–50

In his Letters to Ladies, the American physician Thomas Ewell in 1812 advised women about, among other things, beautifying the skin. It all came down to one important aspect, he argued: ‘the state of the skin depends on the state of the body; that to make it look well, you must make the body healthy’.Footnote 10 The connection between outer beauty and inner bodily health defined by skin has a long history. The conception of the skin as a receptacle for waste and as a layer of exchange with exhaling ‘pores’, and that it thus plays a key role in bodily health, was described already by Plato.Footnote 11 From the sixteenth century onwards, insensible and sensible perspiration appeared in writings on the body as purifying and beneficial for bodily health.Footnote 12 By the early nineteenth century, however, the hygiene of body and skin had become a means to achieve both health and beauty. Beauty and skin care for women were now defined by medical science and doctors’ advice.Footnote 13 Finally, for health reformer Erasmus Wilson the discovery of new anatomical parts inside the skin proved a central component in popular sanitary education from about 1840.

Although many authors of popular physiology books had discussed the role of skin cleanliness for health before this date,Footnote 14 the defining role of skin anatomy for skin cleanliness was made only in 1835.Footnote 15 That year French microscopists Gilbert Breschet and Augustin Roussel de Vauzème published a treatise disclosing the anatomy of the sweat ducts, as was commemorated in an English publication on skin in 1837: ‘It was a great desideratum among English practitioners to have the true anatomy of the skin fully explained and demonstrated (…) but M. Breschet and his confrére seem to have set the question at rest.’Footnote 16 Erasmus Wilson immediately adopted this new anatomy and physiology to explain the importance of healthy skin for sanitary purposes in popular handbooks on cleanliness. Connecting skin as a regulator of animal heat, an organ for the removal of useless materials, and an organ of touch in one anatomical image, Wilson turned skin into a tool for sanitary reform. His efforts to popularise skin anatomy presage the adoption of skin as a symbol for drainage of the body in a sanitary context.

Born the son of a naval surgeon and an artist, the London physician, skin specialist and sanitary reformer William James Erasmus Wilson became known to the general public for his philanthropy and popular books on the skin and cleanliness. Wilson established himself as a surgeon, hygienist and productive author.Footnote 17 In 1840 he started as a lecturer on anatomy and physiology at Middlesex Hospital where he set up his own practice. Later, as a sub-editor of The Lancet,Footnote 18 Wilson became interested in skin diseasesFootnote 19 and soon involved himself in medical establishment circles in London. A paper on the discovery of a new human skin parasite led to his acceptance as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1843.Footnote 20 A successful career as a surgeon and proponent of the study of skin diseased followed, with the foundation of a special journal on skin diseases, the Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Diseases of the Skin, and the establishment of a chair and museum of dermatology at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1869.Footnote 21 In the medical arena, Wilson’s was one of a prominent London physician keen on developing the study and practice of dermatology.

As one of London’s elite practitioners and a wealthy philanthropist, Wilson gained national fame around 1877 when he arranged for the obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle to be transported to its ‘rightful owner’ from Egypt to British ground for around £10 000, using his profits from shrewd investments in gas and railways.Footnote 22 This and his election as president of the Royal Society of the College of Surgeons in 1881 were followed by publications in popular magazines such as Vanity Fair and the Graphic.Footnote 23 The obelisk can still be admired at the Victoria Embankment of the Thames, as a prominent reminder of Victorian nationalism and Wilson’s philanthropy. Other projects more in keeping with his professional interests included his financial support for a new wing and chapel at the Royal Sea-Bathing Infirmary at Margate.

An essential part of Wilson’s public presence was his knowledge of healthy and diseased skin. In 1845 he published the best seller On the Management of the Skin as a Means of Promoting and Preserving Health. This pocket-size volume went through seven editions under different titles and remained in print for thirty-one years, mainly as Healthy Skin: a Popular Treatise on the Skin and Hair, Their Preservation and Management.Footnote 24 The book relates Wilson’s experiences with skin diseases and his involvement with popular physiology and health education. As the title suggests, Wilson extensively discussed the anatomy of the skin and ways to preserve its health in order to maintain and control bodily health in general. In contrast, the abundant gory stories about all kinds of skin affections in the latter part of the book served as a harsh reminder of what could happen if one did not stick to Wilson’s rigid regimen of cleanliness. He introduced a view of the skin anchored in recently acquired anatomical knowledge, but also earlier concepts of cleanliness and health. His purpose was to ‘supply a knowledge of that part of the economy of man which forms the exterior of his body and is more immediately under his own personal control – namely, the SKIN, the NAILS, and the HAIR’.Footnote 25 Against the background of the devastating Asiatic cholera epidemics, Wilson wanted to draw attention to the skin as the primary focus of cleanliness in every sense.Footnote 26 Public bathhouses and washhouses especially drew his attention. He commemorated the success of the first public bath in London at Easton Square in the parish of St Pancras, which had drawn 674 866 people to the establishment since its opening in 1846: ‘[they] have obtained the incalculable blessing of clean skins or clean linen’.Footnote 27Healthy skin, dedicated to hygienist Edwin Chadwick, thus fitted with the emergence of a quest for cleanliness and municipal reforms to improve conditions for the poor in Britain’s crowded cities.Footnote 28

Although Wilson was not the first to discuss skin cleanliness, he promoted an understanding of the skin as an important cleansing agent in the context of recent insights into skin’s complex cellular anatomyFootnote 29 and at the service of sanitary reform of the labouring classes. He meticulously discussed the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the skin, such as the perspiratory system, which consisted of ‘very minute cylindrical tubes’ travelling through the different layers of the skin, regulating the temperature of the body and removing noxious compounds.Footnote 30 The anatomical knowledge of the layers, membranes, organelles and cellular structures of the skin became the foundation for the rules for the management of the skin. As Wilson argued, by processes of formation and growth ‘an action necessary, not merely to the health of the skin, but to that of the entire body, is established’.Footnote 31 Wilson aimed to educate his readers on ways to keep the skin in a healthy state. Anatomy, physiology, diseases, diet, clothing and above all bathing were discussed to this end.

What was Victorians’ understanding of the skin at the time Wilson published Healthy Skin? In general, people regarded the skin as a sensitive covering for the body. It functioned as ‘exhalant of waste matter from the system’, as heat regulator, as a layer for absorption and as seat of sensation and touch.Footnote 32 Describing the (non-visual) anatomy and physiology of the skin, many medical authors relied on the works by the German Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland and the French Xavier Bichat.Footnote 33 Popular magazines discussed a way of finding the pores in the skin with a ‘glass’ as entertainment.Footnote 34 And mothers worried about their babies’ health were taught how to care for their skin.Footnote 35 In general, as a sensitive limit, the skin was understood to have an intimate relation to other excreting organs, such as the lungs, stomach, liver and bowels. Relaxation, stimulation or irritation caused for example by bathing, rubbing or even clothing, influenced the functions of the skin and thus health in general.Footnote 36 Now Wilson and other sanitarians moved skin hygiene into the context of the public health movement.

Wilson argued for skin cleanliness as the essence of both private hygiene and public health.Footnote 37 He called for public health for the masses by creating public washhouses and bathhouses: ‘they are the means of drawing the rich nearer to their poorer brethren; and they enable us to fulfil (…) the Divine injunction, to “love one another”’.Footnote 38 For Wilson, however, public measures were founded in personal care of the skin. He directly addressed the reader’s responsibility for keeping the skin healthy and vital: ‘Health lies in the equilibrium, and the duty of the individual to himself is to pursue that state as nearly as possible’.Footnote 39 He called cleanliness of the skin a ‘household truth’ and ‘value’.Footnote 40 Without regular washing of the skin with water, a crust of impurities from the skin itself, from the atmosphere, and from the clothes would cover the skin. Dust particles, soot, ‘poisonous gases, miasmata and infectious vapours’ would adhere to the skin and cause problems of all kinds.Footnote 41 A growing devotion for ‘tubbing’ played on both the regime of cleanliness for the individual and the working classes.Footnote 42Healthy Skin set the agenda for the skin as the locus of cleanliness rituals, healthy bodies, and moral control of society. If cleanliness was Wilson’s faith, Healthy Skin was his bible.

Wilson’s Healthy Skin was most likely intended for a middle-class audience. Geographically, readership of Healthy Skin spread through Britain and America while the book was also noticed on the continent.Footnote 43 Many subjects discussed in the book, such as proper diet and clothing, exercise and bathing, had appeared in popular health advice books and monthly family health magazines from the 1820s onwards.Footnote 44 Demographically, Wilson likely had in mind a female audience for he often mentioned children and their health. He also insisted on personal hygiene and exercise for the sake of beauty. Furthermore, a review of the book mentioned how Wilson too explicitly scared ‘his lady-readers’ with images of little animals inhabiting the oil glands of the skin.Footnote 45 This elicited a completely different reaction from another reviewer, who even applauded Wilson’s discussion of the so-called Entozoon folliculorum.Footnote 46 Wilson was praised for democratising the dangers of uncleanliness of the skin by showing how ‘refined society’ was just as vulnerable to these animals as were the ‘great unwashed’:

The delicate town-bred lady of fashion, in descending from her carriage, shrinks instinctively from the mass of rags, filth, and vermin, which is brought into continuity with her precious person by some pertinacious beggar; ignorant all the while that her sebaceous follicles give board and lodging to a host of parasites, whose number may equal that of the various kinds of ‘small deer’ that nestle in the matted hair and tattered garments of the fellow-being whom she regards with such loathing.Footnote 47

Such moral use of knowledge of the skin’s anatomy could thus serve a call to bridge class barriers.

Several medical reviews of early editions of Wilson’s treatise were very critical. The Medico-Chirurgical Review argued against Wilson’s discussing too ‘minutely the anatomy of the skin’ and his popular descriptions of diseases and treatments, in particular his advocacy of hydropathy.Footnote 48 A man of his professional status and standing should not busy himself with the popularisation of professional knowledge; that would be ‘useless and ridiculous’.Footnote 49 An extensive review in the British and Foreign Medical Review argued that popular hygiene had been discussed much better by others before Wilson, for example in the work of Andrew Combe.Footnote 50 Still, Healthy Skin was considered important to ‘forward the “bath and wash-house” movement; which, combined with those which are taking place of early shop-closing, of draining and ventilation, and of public places of recreation, we look upon as the most pleasing and favorable of the “sign of the times”’.Footnote 51 A review in the American Medical Examiner was wholly positive, praising the popular treatise as an ‘excellent popular exposition’ and ‘an agreeable work’.Footnote 52

In the religious and popular press, Healthy Skin was much praised and quoted. The American journal The Biblical Repository and Classical Review called Healthy Skin a medical work, yet ‘of value to every person’.Footnote 53 Other positive reviews appeared for example in the The Living Age and in The Eclectic Magazine, which reprinted articles from The Spectator in 1846 and from the British Jerrold’s Magazine in 1847.Footnote 54 The review of 1846, praised Wilson’s work for its successful popularisation of the topic: ‘it is a lucky subject; for we all have a skin, and our health greatly depends upon its health’.Footnote 55 The book could not be ‘too highly prized’.Footnote 56 An extensive editorial review in the Methodist magazine The Ladies’ Repository, a monthly periodical on literature and religion, discussed Wilson’s findings on the skin at length.Footnote 57 Anatomical characteristics, interesting facts and advise about bathing and skin health appeared in the editorial. The importance of bathing was put in direct relation to the anatomical make-up of the skin:

Every moment of one’s life a multitude of useless, corrupted, and worn-out particles evaporate through the numberless small vessels of the skin in an insensible manner, and if these are not promptly and properly removed you will have to pay for your indiscretion with compound interest (….) The way most people act would indicate that water was poisonous as a general wash, and that soap was a powerful irritant. Away with such nonsense. There does not exist in the art of living a greater device for securing a vigorous and buoyant existence than bathing.Footnote 58

Besides his promotion of bath and washhouses, Wilson’s vivid and appealing description of the perspiratory system was quoted over and over again throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. In a time of growing concern about drainage, sewage, and ventilation in the middle-class house and the city his discussion of the tasks performed by the skin, perspiration in particular, hit a nerve.

Uncleanliness and ‘the Skins of the Metropolis’ 1850–80

From the 1840s, calls for skin cleanliness became a tool for hygienists in the sanitary reform of the home and the city. In a passage from Healthy Skin, Wilson drew an analogy of the skin to the city’s sewage system that was immensely popular for the remainder of the nineteenth century. In popular physiology and health books on human anatomy, authors connected Wilson’s drainage analogy to pictures of the microscopical make-up of the skin, as well as to experimental proof of the importance of skin for health. Images of the skin with its own ‘plumbing’ finally played a crucial role in the dissemination of the idea of a healthy functioning skin within sanitary reform.

For Victorians around 1850 there was little in society or nature not related to their health. Architecture, science, engineering, politics and economics all influenced the body in one way or another.Footnote 59 Public health authorities and sanitary reformers acted through engineering, control, regulation and sewage systems to ensure proper living conditions in cities and lowering of mortality rates. In particular, the ‘sewerage doctrine’ by the famous sanitarian Edwin Chadwick included measures for drainage of waste waters from houses through pipes. This was the scene for Wilson’s writings: a society preoccupied with water and wastesFootnote 60; a society moving towards modern sanitation, less stench, less noxious gases, less death.

One of the most frequently quoted passages from Wilson’s book on healthy skin was his calculation of the length of the marvellous and extended perspiratory system. He used this passage to stress the importance of the skin and to endorse washing as a way to ‘manage’ and control health:

To arrive at something like an estimate of the value of the perspiratory system in relation to the rest of the organism I counted the perspiratory pores in the palm of the hand, and found 3528 in a square inch. Now, each of these pores being the aperture of a little tube of about a quarter of an inch long, it follows, that in a square inch of skin on the palm of the hand there exists a length of tube equal to 882 inches, or 73![]() $\def \xmlpi #1{}\def \mathsfbi #1{\boldsymbol {\mathsf {#1}}}\let \le =\leqslant \let \leq =\leqslant \let \ge =\geqslant \let \geq =\geqslant \def \Pr {\mathit {Pr}}\def \Fr {\mathit {Fr}}\def \Rey {\mathit {Re}}{\frac12}$ feet. Surely such an amount of drainage as seventy-three feet in every square of skin, assuming this to be average for the whole body, is something wonderful, and the thought naturally intrudes itself: – What if this drainage were obstructed? Could we need a stronger argument for enforcing the necessity of attention to the skin? (…) To obtain an estimate of the length of tube of the perspiratory system of the whole surface of the body, I think that 2800 might be taken as a fair average of the number of pores in the square inch, and 700 consequently, of the number of inches in length. NOW, THE NUMBER OF SQUARE INCHES OF SURFACE IN A MAN OF ORDINARY HIGHT AND BULK, IS 2500; THE NUMBER OF PORES, THEREFORE, 7 000 000, AND THE NUMBER OF INCHES OF PERSPIRATORY TUBE 1 750 000, THAT IS, 145 833 FEET, OR 48 600 YARDS, OR NEARLY TWENTY-EIGHT MILES.Footnote 61

$\def \xmlpi #1{}\def \mathsfbi #1{\boldsymbol {\mathsf {#1}}}\let \le =\leqslant \let \leq =\leqslant \let \ge =\geqslant \let \geq =\geqslant \def \Pr {\mathit {Pr}}\def \Fr {\mathit {Fr}}\def \Rey {\mathit {Re}}{\frac12}$ feet. Surely such an amount of drainage as seventy-three feet in every square of skin, assuming this to be average for the whole body, is something wonderful, and the thought naturally intrudes itself: – What if this drainage were obstructed? Could we need a stronger argument for enforcing the necessity of attention to the skin? (…) To obtain an estimate of the length of tube of the perspiratory system of the whole surface of the body, I think that 2800 might be taken as a fair average of the number of pores in the square inch, and 700 consequently, of the number of inches in length. NOW, THE NUMBER OF SQUARE INCHES OF SURFACE IN A MAN OF ORDINARY HIGHT AND BULK, IS 2500; THE NUMBER OF PORES, THEREFORE, 7 000 000, AND THE NUMBER OF INCHES OF PERSPIRATORY TUBE 1 750 000, THAT IS, 145 833 FEET, OR 48 600 YARDS, OR NEARLY TWENTY-EIGHT MILES.Footnote 61

This passage touched the imagination of many audiences throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. It was used over and over again in Anglo-American medical, popular and educational literature well into the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 62 The strength of the calculation relied upon the idea of such an immense length of drainage tubes within such a thin layer of the body. In industrialised societies, the advent of the steam train and steamship was changing people’s experience of distance and time.Footnote 63 As the Essex surgeon John Coventry noted in reference to Wilson’s calculations of man’s twenty-eight miles of perspiration tubes: ‘(…) an hour’s railway ride, forsooth! (…) we shall arrive at something like an appreciation of the importance of keeping this pipeage pervious.’Footnote 64

Wilson’s popular call for the importance of the skin found fertile soil in health education literature for women, workers and children. The American physician Calvin Cutter, for example, copied large parts of Wilson’s writings on skin cleanliness in his textbooks on anatomy and physiology designed for schools and colleges.Footnote 65 Keeping Wilson’s calculations on perspiration in mind, management of the skin also became part and parcel of the literature on cosmetics.Footnote 66 Skin cleanliness was of interest not only to the female audience, but also for men’s work practices. In The Farmer’s Magazine, the passage on the perspiratory system was transposed to the health of dairy cattle, as to demonstrate the importance of cleaning the cows.Footnote 67

In the context of sanitary reform, Wilson’s popularisation of experimental and microscopical researches on the skin provided a confirmation of the ancient belief that clogged skin pores caused diseases and disaster.Footnote 68 As the Reverend Charles Hole stated in his Practical Moral Lesson Book, ‘Think of the twenty-eight miles of drainage in the human body being blocked up by uncleanliness! Is it not a wonder that unclean persons have any health at all?’.Footnote 69 Imagine what would happen if such an extended system of drainage for the body was clogged up with dirt. Neglect proper bathing and disease could ‘hold a revel’ with the organs.Footnote 70

Wilson secured his arguments for skin cleanliness first by his popular translation of recent French experimental research on the physiology of the skin. Physiologists developed a special interest in the role of the skin for balancing and the exchange of gases and fluids from around the 1830s.Footnote 71 In the following decade French and German physiologists performed animal experiments in an attempt to explain the respiratory and perspiratory functions of the skin. In Healthy Skin, Wilson discussed the experiments on animal temperature by Fourcault, as well as experiments done by Alfred Becquerel and Gilbert Breschet.Footnote 72 These experiments showed that rabbits, horses and birds whose skin was covered with a thick layer of impermeable varnish apparently asphyxiated and died.Footnote 73 The impact of these experiments was reinforced by part of Fourcault’s experiments recounting the striking story of a boy who’s skin was covered in gold on the occasion of the election of pope Leo X and died soon after.Footnote 74

Figure 1: Microscopical depiction of skin in Healthy Skin: A Popular Treatise on the Skin and Hair, Their Preservation AND Management (1853). Reproduced with kind permission of the Wellcome Library, London.

Wilson’s entertaining calculations had serious consequences and the functions of skin should not be underestimated. In an article in the Scientific American from 1863 on the ‘Wonders of the Skin’ both Fourcault’s experiments and Wilson’s calculations were discussed, without mentioning their names however, concluding: ‘The skin, although so simple in appearance, affords a beautiful illustration of the infinite skill and wisdom of the great Creator, not only in its wonderful structure, but with respect to all its varied functions’.Footnote 75

In addition to the link with experimental research on the skin, Wilson also managed to connect the newly introduced microscopical imaging of the skin and its sweat ducts to his calculations. Following the diagrammatic illustrations of Breschet and de Vauzème, Wilson incorporated a recent standard microscopical depiction of a cross section of skin in his popular work (Figure 1).Footnote 76 From now on, in works on human physiology Wilson’s calculations of the perspiratory ducts were connected to the discoveries and visual diagrammatic representations of Breschet and de Vauzème.Footnote 77 This combination of visual imagery with recent experimental research and Wilson’s calculations found its way to popular literature on the skin. The authors of The Family Cyclopaedia of 1859, for example, presented a diagram of the structure of the skin with Wilson’s numbers on drainage as useful knowledge.Footnote 78

Figure 2: Cross-section of London Holborn Viaduct, showing the city sewerage. A section through the roadway of Holborn Viaduct, London: looking east, showing the middle level sewer. Wood engraving after W. Haywood, 1854. Reproduced with kind permission of the Wellcome Library, London.

Soon after the appearance of Healthy Skin, hygienists positioned Wilson’s attention to the skin as a tool in the moral and political call for cleanliness of the masses. In an article in The Lancet in 1846, Essex surgeon John Coventry addressed the ‘The Mischiefs of Uncleanliness and the Public Importance of Ablution’.Footnote 79 Contrary to what this title might merely suggest, Coventry mainly called for attention to hygiene, and ablution in particular, while seeking ‘to elucidate the various evils of dirtiness as deduced from the structure and functions of the skin’.Footnote 80 Drawing on many of Wilson’s ideas, Coventry reaffirmed that the skin, so ‘consentaneous’ in its operations, influenced health in many ways and, therefore, must be kept in the utmost proper condition.Footnote 81 Most importantly, Coventry drew a direct connection between the broader issue at hand, namely the state of hygiene and sanitation in Britain, to the situation of skin cleanliness and health. The skin, being ‘the grand drainage-pipe of body’ reflected the state of the sanitation and sewage in the city:

Having traced so large an amount of disease and misery to uncleanliness, how deeply must we regret that London is still the ‘great unwashed’, as tightly packed as the hides in a tanyard. From year’s end to year’s end, the skins of the metropolis, ‘glazed and varnished’, reek in their accumulated sordes, to the sad detriment of comfort, comeliness, health, and longevity.Footnote 82

The analogy between the skin as indispensable bodily drainage system and the necessity of proper city sewage and bathing facilities was crucial.Footnote 83 While Wilson himself in early editions of Healthy Skin alluded to a similar metaphor, his discussion of the skin in his book on the Turkish bath was even more striking. In The Eastern, or Turkish Bath: Its History, Revival in Britain and Application to the Purpose of Health (1861), Wilson referred to the skin as a “‘sanitary commissioner,” draining the system of its impurities’.Footnote 84 In a slightly different way, Coventry’s article in The Lancet also made a connection between the skin (pores) and cleanliness of body and society at large:

[W]e hope that every facility may be afforded for public bathing; that cleanliness may no longer be viewed as a luxury accessible only to the wealthy, but that, before the ensuing parliamentary session, the pores, as well as the ports, of our mother country may be rid of their imposts, and unreservedly thrown open.Footnote 85

The work by Edwin Chadwick also focused on the parallels between skin and subterranean drainage. In the well-known report on the sanitary conditions of the labouring classes, the term ‘drainage’ obviously occurs many times.Footnote 86 Yet in a later article dedicated specifically to skin cleanliness, Chadwick described the skin as the last stage of the ‘sewage’ of the body.Footnote 87 He argued for the education of children in schools as the first step towards hygienic reform. His crusade against ‘the sanitary evil of personal filth’ required a regular cleaning of the skin as a disciplinary ritual for children.Footnote 88 Thus, the skin becomes for the body what drainage and sewage should be for the city. This is why Wilson’s quote about the skin’s twenty-eight miles of drainage was such a powerful and almost tangible explanation. These tubes directly connected cleanliness of the body to the house, and the house to the city.

From the 1870s, the health of body, house and city became one. As medical historian Annmarie Adams has shown, physicians of the Domestic Sanitation Movement applied principles of physiology to architecture and in so doing treated body, house, and city as part of a single system.Footnote 89 Obsessed with drainage, sanitarians urged the removal of all waste from the house and the city via well-designed intestines, while, as Pamela Gilbert has argued, analogies of body and home cleanliness were also directed towards women in an effort to prevent the spread of epidemic disease.Footnote 90 Skin had been a particularity gratifying subject for analogy ever since Erasmus Wilson articulated its physiology as a tool for sanitary reform by stressing drainage, plumbing and exhalation.Footnote 91 With its sweat ducts taken as drains and sewers of the body, the anatomy of the skin was visually transposed onto the sewerage system of the house and the London city in cross-section imagery (compare figures 1 and 2).Footnote 92 When Chadwick in 1875 wrote on the importance of clean streets for the prevention of disease and mortality, he alternately stressed skin cleanliness for children and the dangers of ‘excrement-sodden’ street surfaces.Footnote 93 Moving between the skins of playing children and the urban filth in the street, Chadwick put skin cleanliness on the same level as city cleanliness. The surfaces of the body and the street, both had to be rid of the evils of waste.

Skin cleanliness as proposed by Wilson and other sanitarians stressed evacuations of waste and symbolised the promise of control over health and disease. To act on skin cleanliness, one thing was indispensable: soap. I will next discuss how soap advertisements from the Pears’ soap company became a visual analogy for the removal of unwanted moral ‘wastes’ and the consequent promise of health and beauty.

Figure 3: Pears advertisement showing monks washing and shaving with endorsement by Erasmus Wilson. Lithograph after H. Stacy Marks; after 1881. Reproduced with kind permission of the Wellcome Library, London.

Soap Advertising 1870–1900: Imprinting the Morality of Healthy, White Skin

Dirt, as Lord Palmerston defined it, is ‘matter in the wrong place.’ To remove this to the right place, so far as the human being is concerned, and to remove it without detriment to the health of the skin, is the function of soap.Footnote 94

If skin provided the necessary drainage of waste materials through its plumbing, soap was indispensable to remove unwanted matter. Soap manufacturers such as Pears’ presented the soap bar as a medium that would rid the skin of all unwanted ‘dirt’, thereby turning skin into locus of control over body, race and beauty. Supported by the scientific knowledge of the workings of the skin, Erasmus Wilson and others became prominent public figures in Pears’ soap advertising.Footnote 95 Wilson’s endorsements figured alongside religious depictions of monks defining cleanliness ‘next to godliness’ (see Figure 3). The ideal of a white, morally uplifted, unspoiled, civilised, beautiful skin could be achieved by removing ‘dirt’ and letting the perspiratory system work freely.

Skin cleanliness became part of mass-media advertising in the Pears campaign after 1865. Around the middle of the nineteenth century, the London-based firm A. & F. Pears developed from a small enterprise into a large, well-known commercial business, partly due to the remove of the excise on soap in 1853. The industrial production of everyday products such as soap created a culture of mass consumption from the 1850s onwards.Footnote 96 A resourceful man with insights into publicity, Pears’ business associate Thomas Barratt completely changed the marketing and distribution system for Pears.Footnote 97 His campaigns set the tone for a new way of advertising. One of Barratt’s famous stunts involved the distribution and circulation of coins imprinted with the name ‘Pears’ throughout Britain. In the 1880s, Pears spent around £30 000–40 000 pounds per year on advertising their soap.Footnote 98 Barratt also used the authority of prominent skin specialists, chemists and doctors in the Pears campaign. One of them was Erasmus Wilson.Footnote 99

Figure 4: (Colour online) Advertisement for Pears’ soap featuring Erasmus Wilson. Undated. Reproduced with kind permission of the Wellcome Library, London.

As a recognised and well-known public ‘specialist on the skin’, Wilson was the perfect candidate to endorse Pears’ transparent soap and his name appeared repeatedly in Pears advertisements from the 1860s on (see Figure 4).Footnote 100 Wilson’s endorsements for Pears’ soap originated partly from his own medical works. In Healthy Skin he referred to soap as an ‘indispensable aid’ and as a tool to ‘preserve the skin in health’.Footnote 101 In an article on toilet soaps in the Journal of Cutaneous Medicine, he also advocated the use of soap for beauty purposes:

We once knew a beautiful woman, with a nice complexion, who had never washed her face with soap all her life through; her means of polishing were, a smear of grease, eg. cold cream, then a wipe, and then a lick with rose-water. Of course we did not care to look too closely nor to approach too closely such an avowal; and we have met in the world with persons so unfortunate as to be unable to bear soap to their skin at all. We pity both; for soap is the food for the skin. Soap is to the skin what wine is to the stomach, a generous stimulant; and a solvent to boot of the surface which holds the dirt.Footnote 102

According to Wilson, soap was indispensable for the control and management the skin. Moreover, Wilson explicitly mentioned Pears’ soap in this article. He articulated his love for the magic substance, assessing Pears’ transparent soap as ‘an article of the nicest and most careful manufacture, and scentless or scented, one of the most refreshing and agreeable of balms to the skin’.Footnote 103 Within a few years, this statement would be quoted repeatedly in Pears’ advertisements in newspapers, magazines and on posters in the city streets and objects such as bookmarks.

The close connections between Wilson and Pears did not go unnoticed. On several occasions, Wilson was accused of commercial exploitation of his name and reputation. In a letter to the editor in The Lancet in 1864, Wilson defended himself against some critical questions posed by an anonymous reader.Footnote 104 In response to the accusation that he sold his name to all kinds of ‘hairwashes and pomades’ Wilson responded that he could not escape the commercialisation of his name: ‘It has happened to others as well as myself, and we see daily the names of eminent men associated with popular remedies of various kinds prepared from their prescriptions. I can only say that I have not encouraged this practice in my own instance’.Footnote 105 With regard to Pears in particular, a letter on the issue of an implied partnership between Wilson and Pears explains the sensitivities. The letter, dated 1878, was probably written by Wilson’s business representative.Footnote 106 The author explicitly denied a direct partnership between Wilson and the soap maker. Apparently, Mr Pears had met with a member of the medical profession and stated that he had a partnership with Mr Erasmus Wilson. The aim of the author of the letter was to firmly deny all communication between Pears and Wilson:

I know that Mr Wilson has never had any communication with Messrs. Pears firm except through myself. I had some months ago to compel the Firm under threat of proceedings by Injunction to alter at a great expense the whole of their advertisements and this they have done – and with the exception of this I know that Mr Wilson has never had anything to do with them – Indeed I doubt if there is such a person as Pears in existence and I only regret I was unable to remove from the advertisement all mention of Mr Wilson’s name, but I could not do so as a statement to the effect of that made in the advertisement was incautiously inserted in a work edited by Mr Wilson.Footnote 107

Despite this statement we may assume that Wilson did not take any action to remove his name from the advertising campaign, since later advertisements still featured his name. Wilson’s appearance in the Pears advertisements, wanted or unwanted, created a visual connection between medical expertise, skin cleanliness and soap.

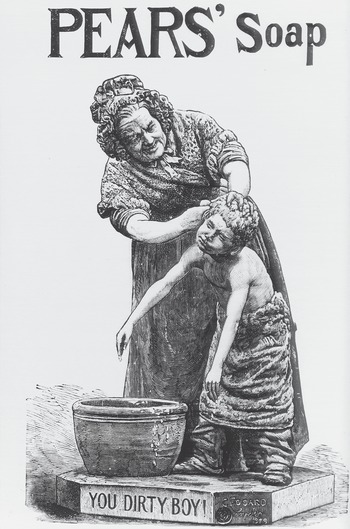

In soap advertising, control over dirt removal was visually encouraged in three ways. First, advertisements reinforced the discourse of the removal of the undesired behaviour of the lower and working classes. This is represented, for example, in the so-called ‘You Dirty Boy’ advertisement (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: ‘You Dirty Boy’ advertisement for Pears’ soap. Illustrated London News, 14 December 1889, 778. Reproduced with kind permission of the Courtauld Institute of Art.

The humorous image of a young, ragged boy having his ears washed by an old woman was based on a famous statue by London-based artist Giovanni Focardi (1842–1903) and commissioned by the A. & F. Pears Company for the Paris World Fair ‘Exposition Universelle’ of 1878. As Pears owned the right to make copies and use them as advertisements for Pears’ soap, small-scale terracotta versions were spread around Great Britain and United States. For audiences of the time, the power of the representation lay in its ‘irresistibly droll performance’ that everybody recognised: ‘for most of us have had grandmothers, and more of us have violently objected to having our faces washed’.Footnote 108 In Paris alone, hundreds of thousands of visitors admired the statue. The image was used as advertisement shop stand, trade card and postcard. It figured prominently in the stand of Pears at the International Health Exhibition in London 1884 (see Figure 6). Pears thus often played on the contrast between the innocence of children versus disobedient youth.Footnote 109 To rid the body of its bad behaviour through the skin was of a type with the religious cleansing of sin (see Figure 3).

Figure 6: ‘You Dirty Boy’ statue by Giovanni Focardi as part of the Pears’ soap stand at the International Health Exhibition. Illustrated London News, 2 August 1884, 101. Reproduced with kind permission of the Courtauld Institute of Art.

A second analogy to the removal of unwanted ‘matter’ in soap advertising concerns the representation of ethnic stereotypes and the whitening of the skin of uncivilised black people. In historical analyses of soap ads, the colonial context and racial connotations are linked to imperial power relations.Footnote 110 The process of washing away ‘uncivilised’ black skin suggested possibilities of social movement. As Ann Mclintock argued with the image of a black toddler washing himself: ‘In the Victorian mirror, the black child witnesses his predetermined destiny of imperial metamorphosis but remains a passive racial hybrid, part black, part white, brought to the brink of civilization’ (see Figure 7).Footnote 111

Figure 7: Advertisement for Pears’ soap. ‘Pears’ transparent soap for improving the complexion. Pure, fragrant, durable.’, 1884 (folding sheet, 22cm). Reproduced with kind permission of the British Library Board (Evan. 7538).

Contemporaries reacted with laughter to the ‘highly humorous’ dual picture of the black boy washing his black body, but not his face, white with Pears’ Soap.Footnote 112 The effectiveness of soap on the skin, as testified to by authorities like Erasmus Wilson, was so ‘refreshing and balmy’ that it cleansed only those parts in contact with the water.Footnote 113 The opposite was seen in the ‘Dirty Boy’ ad, where the face was the only thing left to be rid of dirt. The implicit message of the ads was that Pears’ soap could relieve the skin of unwanted dirt and skin colour.

A third and last analogy to waste removal in Pears advertising stressed beauty. The connection between a healthy skin system and (white) beauty was indicated with the slogan ‘Matchless for the complexion’. In beauty guides the connection between healthy skin and beauty was promoted with physiological facts about the workings of the skin system. In What Our Girls Ought to Know, for example, natural history teacher Mary Studley in a chapter on how to become beautiful referred to the lesson that ‘all beauty must be organic’ when discussing skin.Footnote 114 To stimulate the excretory power of the skin using water was good ‘physiological management’ for a girl to obtain a ‘radiant halo’.Footnote 115 Pears advertising alluded to this connection between the physiological management of the skin system and beauty resulting from that. One ad typically quoted both Erasmus Wilson about the beneficial workings of soap for the skin and Adelina Patti on her experience with the soap for the complexion. Opera singer Patti, like actress Lillie Langtry, figured prominently in many Pears soap advertisements.Footnote 116 Since Patti was one of the most photographed women of the Victorian era, the public connection between her beauty and Pears soap was easily reinforced. With its radiant, enamel-like surface gleaming amid the heavy dark-line engravings, the face was the focal point in advertisements that held the promise of a beautiful complexion (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Opera singer Adelina Patti in an advertisement for Pears’ soap. Undated. Reproduced with kind permission of Lebrecht Music & Arts.

Conclusion

Advertisements for Pears soap can be taken as constitutive of late Victorian visual body culture.Footnote 117 Soap advertisements generated an ideal of control over waste removal analogous to the subterranean sewage systems in homes and city streets. Paradoxically, while the abundance of soap advertisements stressed a visual healthy skin, cleanliness lost its visibility.Footnote 118 Yet the multi-layered artistic exposition of skin referred to control over skin colour, beauty and behaviour. The reality of modern city life for the middle class (women especially) meant that there was a real possibility of coming into contact with dirt, visible or invisible. The modern-life painting by George William Joy The Bayswater Omnibus (1895) shows a scene in which Pears’ soap advertisements are visible in the background (see Figure 9). In the cramped space of the omnibus, body contact between man and woman or between people of different classes was unavoidable.Footnote 119 The fair skin of the fashionable young woman on the viewer’s left of the painting and the milliner to her left, run the chance of getting dirty on the trip.

Figure 9: (Colour online) Pears’ soap advertisement in The Bayswater Omnibus by G.W. Joy, 1895. Reproduced with kind permission of the Museum of London (www.museumoflondonimages.com). Due to copyright restrictions the high-resolution version is only available in the printed version of the journal.

In another narrative painting by George Earl, Going North, King’s Cross Station (1893), a Pears’ soap ad offers the promise of washing away the dirt that comes from contact with people of various social classes and the filth of the city for fashionable middle-class women.Footnote 120

During the nineteenth century, people’s conception of skin was greatly influenced by developments in sanitation for living spaces. For physicians like Erasmus Wilson, the analogy between the sewerage of the skin and that of the house or city proved an effective way of promoting his popular message to the rising middle class. Draining body and society of unwanted matters, reminded to city life and the constant flux of wastes that demanded control.

In addition to deepening our understanding of skin cleanliness and Victorian body culture, this article demonstrates the ways in which visual representations of healthy skin functioned in household handbooks, popular literature and city life. The popularisation of microscopical imagery and its analogy to municipal sewage systems defined skin cleanliness as way to rid body, city and society of unwanted dirt, disease and contact. A focus on skin reveals the connections between the personal space of the body, the home and the city. Promoting the practice of cleaning the skin strengthened the links that reformers sought to make between the health of the individual, the city and society at large.