Introduction

Subglacial erosion rates range over many orders of magnitude, from among the slowest to among the fastest observed in common geomorphic environments (Koppes and Montgomery, Reference Koppes and Montgomery2009). Retreat of slow-moving, cold-based glaciers occasionally reveals unaltered relict surfaces with rooted plants (e.g. Lowell and others, Reference Lowell2013). Data from numerous glaciated basins, on the other hand, reveal sediment yields of comparable magnitude to the fastest-eroding bedrock fluvial systems (Hallet and others, Reference Hallet, Hunter and Bogen1996; Koppes and Montgomery, Reference Koppes and Montgomery2009). Even very slow erosion may be geomorphically important if sustained over long-lasting glaciation (Cuffey and others, Reference Cuffey2000), such as the >30 million year duration of Cenozoic Antarctic ice cover (Pagani and others, Reference Pagani2011). Here, however, we will focus on conditions that produce the average to high subglacial erosion rates, mostly of order 10−4 to 10−2 m a−1, though lower rates of order 10−5 m a−1 can prevail on hard substrates.

Much of the work in recent decades on landscape evolution by glacial erosion assigns primary importance to the sliding velocity as a controlling variable (e.g. Oerlemans, Reference Oerlemans1984; MacGregor and others, Reference MacGregor, Anderson, Anderson and Waddington2000), or uses ice discharge as a convenient proxy for it (e.g. Anderson and others, Reference Anderson, Molnar and Kessler2006). Indeed, theoretical analyses of abrasion provide a clear motivation to do so (Hallet, Reference Hallet1979), while for quarrying the dependence on the sliding rate is important but complicated by other, inter-related factors such as effective pressure and ice-bed contact area (Hallet, Reference Hallet1996; Iverson, Reference Iverson2012). At least one observational analysis demonstrates an increase of erosion rate with faster sliding beneath an active glacier (Herman and others, Reference Herman2015). In addition, numerical landscape models that specify erosion rate as a function of sliding can produce topographies that resemble real glacially-modified landscapes in essential ways (e.g. Herman and Braun, Reference Herman and Braun2008; Pedersen and Egholm, Reference Pedersen and Egholm2013; Pedersen and others, Reference Pedersen, Huismans, Herman and Egholm2014), though all such models operate within the constraint that accurate prediction of sliding rate itself remains an unsolved glaciological problem (Cuffey and Paterson, Reference Cuffey and Paterson2010).

Several lines of evidence, however, are inconsistent with dominant control by sliding. Glaciers in Patagonia erode much faster than dynamically-similar glaciers in the Antarctic Peninsula, a difference likely attributable to the greater abundance of surface melt in Patagonia (Koppes and others, Reference Koppes2015; Fig. 2d of that paper shows, in addition, no discernible relationship between erosion and sliding rate within each of these two regions). Large outlet glaciers around the Antarctic ice sheet have existed and flowed rapidly for tens of millions of years, without producing a geomorphological signature substantively distinct from the fjords of Norway and Patagonia. Overdeepenings manifest deep erosion in the outer regions of glacial valleys, where time-averaged discharges are not large (Herman and others, Reference Herman, Beaud, Champagnac, Lemieux and Sternai2011).

As others have suggested (Hooke, Reference Hooke1991; Hallet, Reference Hallet1996; Herman and others, Reference Herman, Beaud, Champagnac, Lemieux and Sternai2011; Koppes and others, Reference Koppes2015), dependencies of erosion mechanisms on glacial hydrologic phenomena provide a likely explanation for the partial disconnection of erosion and sliding. Plausible hypotheses include: (1) melt derived from the surface flushes the glacier bed clean of sediment, allowing abrasion and quarrying to proceed; (2) subglacial water flows concentrated in channels incise directly into bedrock by the mechanisms known to operate in subaerial streams; (3) rapid fluctuations of water pressure at the glacier bed, related to temporal variations of surface melt and its drainage, create a disequilibrium between cavity sizes and water pressures, allowing the load of the glacier to focus on small regions and enhance quarrying and perhaps abrasion and (4) the coupled mechanics of the ice–water–rock interface allows for brief, very rapid slip events that produce pulses of extreme high or low pressures that promote fracture growth in rock and quarrying.

In this context, we aim to provide a selective and somewhat idiosyncratic perspective on controls and time-variation of subglacial erosion, drawing both on recent research and our own thinking, and to comment on prospects for further research. Most of our discussion concerns rapid erosion beneath glaciers, but we will end by considering headward erosion in cirques, another facet of erosion in glacial landscapes for which sliding rate cannot be viewed as a dominating variable.

Cleaning up

‘The universe is finished; the copestone is on, and the chips were carted off a million years ago.’ Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, ch. 2, 1851

Drillers, woodworkers, machinists, masons and others who cut or shape materials know that efficient work requires removing the chips, swarf, sawdust, turnings, filings or shavings. Failure to do so slows and then stops progress, as the loose material becomes a lubricating layer between the tool and the workpiece. Similarly, tectonic faults may become lubricated by fault gouge (e.g. Carpenter and others, Reference Carpenter, Saffer and Marone2012).

Till is the swarf, sawdust or fault gouge of glaciers. Some abrasion probably occurs beneath sufficiently thin deforming till (Cuffey and Alley, Reference Cuffey and Alley1996), and might be faster if the till becomes compacted and acts as a rigid mass sliding over bedrock rather than deeper till (Truffer and others, Reference Truffer, Harrison and Echelmeyer2000). More typically, however, till is an efficient suppressor of bedrock erosion, because it smooths the bed to reduce stress concentrations, damps water-pressure fluctuations that might contribute to bedrock erosion (see below), and distributes deformation over a considerable thickness or localizes deformation away from the rigid bed and close to the base of the ice.

Rapid bedrock erosion thus requires till removal. Efficient till removal, in turn, is primarily achieved by subglacial streams fed by surface meltwater reaching the bed through moulins (e.g. Alley and others, Reference Alley1997; Koppes and others, Reference Koppes2015). We discuss such a role for subglacial water next, but first briefly review evidence that other mechanisms typically do not remove sediment rapidly.

A mechanically strong bedrock (one that is well-consolidated, consisting of interlocking crystals or thoroughly cemented particle networks, and with few pre-existing fractures or bedding planes) may erode at such a low rate that the subglacially-generated material is all removed and the bed remains clean. Thus we need to emphasize that ‘rapid bedrock erosion requires till removal’ is a different claim than ‘a bed free of till erodes rapidly’; the latter may or may not be true, depending on both glacier and substrate properties. We do not carefully consider the role of variable bedrock resistance to erosion, but it is clear that erosion is faster in some places than others because of variations in rock characteristics (e.g. the Laurentide ice sheet eroded numerous lakes where it flowed off the crystalline Canadian Shield onto surrounding sedimentary rocks, as noted by Bruce (Reference Bruce1939; who cites Suess' 1883–1909 Das Antlitz der Erde, The Face of the Earth; variations in rock characteristics also affect paraglacial slope stability following deglaciation, as addressed below)).

Limited debris transport in basal ice and by subglacial deformation

An extensive review of mechanisms of till removal via entrainment of basal sediment into glaciers was provided by Alley and others (Reference Alley1997; section 4). Possible mechanisms include entrainment during regelation across or into the bed, debris trapping during net freeze-on by conductive cooling or glaciohydraulic supercooling, deformational processes (thrusting, folding, or upward mixing of debris-bearing basal ice), and filling of basal crevasses. The evidence summarized in that review indicates that these processes are generally inefficient and thus do not entrain sediment rapidly. In many situations, basal ice flows downward toward the bed due to basal melting or longitudinal extensional flow, suppressing entrainment by any of these mechanisms. Structural entrainment via thrusting or folding is generally limited to special locations, such as thawed-to-frozen boundaries, or to ice-marginal situations.

Understanding of these topics has advanced since 1997. The literature on regelation into the bed is now notably richer (e.g. Iverson and Semmens, Reference Iverson and Semmens1995; Iverson, Reference Iverson2002; Rempel, Reference Rempel2008). Ensminger and others (Reference Ensminger, Alley, Evenson, Lawson and Larson2001) documented basal crevassing entraining limited sediment in a situation with an exceptionally well-lubricated bed and high basal water pressure, but observed examples of this process remain rare. Basal thrusting (e.g. Larsen and others, Reference Larsen, Kronborg, Yde and Knudsen2010), folding (e.g. Moore and others, Reference Moore2012) and mixing (e.g. Bender and others, Reference Bender, Burgess, Alley, Barnett and Clow2011) have been elucidated further.

Widespread basal freeze-on of the Siple Coast ice streams has been documented better, and the odd situation responsible for this behavior clarified (e.g. Christoffersen and others, Reference Christoffersen, Tulaczyk and Behar2010). The water freezing onto the base originates as melt under thick inland ice in a region of high geothermal flux (e.g. Cuffey and others, Reference Cuffey2016). Ice thins significantly as it flows into the ice streams, which accelerate down-flow due to increased lubrication provided by thick, extensive, tills and high basal water pressures (e.g. Peters and others, Reference Peters2006). Thinning, in turn, steepens basal temperature gradients, driving freeze-on, while effective lubrication by the sub-ice-stream till allows the fast flow to occur with minimal frictional heating (fast flow transfers resisting stress to the lateral margins, so frictional heating at the bed declines too). The preexisting till is developed from unlithified marine sediments deposited during deglacial intervals (Kingslake and others, Reference Kingslake2018). Thus, in this situation freeze-on of basal sediment beneath the Siple Coast ice streams is not indicative of rapid, widespread bedrock erosion, nor does it generate sediment fluxes comparable to the higher values observed by Hallet and others (Reference Hallet, Hunter and Bogen1996).

Overall, these advancements have improved understanding and reinforced prior knowledge. Debris entrainment into basal ice is generally much too slow to balance the faster observed rates of subglacial erosion.

Till deformation beneath glaciers transports sediment as well, and can convey significant volumes (Alley and others, Reference Alley, Blankenship, Rooney and Bentley1989; Clark and Pollard, Reference Clark and Pollard1998). Nonetheless, the rapidly deforming layer is likely thin (Zoet and Iverson, Reference Zoet and Iverson2018), and its upper surface moves with, or more slowly than, the ice sole, limiting sediment flux, while erosion is suppressed beneath the deforming till. Bedrock erosion beneath an ice sheet can occur balanced by till flux in a deforming bed, but not at very high rates (e.g. Pollard and DeConto, Reference Pollard and DeConto2003, Reference Pollard and DeConto2020).

Rapid, sustained bedrock erosion thus requires sediment transport in subglacial streams to remove the till and allow continuing erosion. In turn, as discussed next, this largely (although not entirely) restricts rapid erosion to times and places with surface meltwater reaching the bed through moulins, and raises important questions about the dynamics of interaction between streams and sediment.

Need for moulins to drive rapid subglacial-fluvial transport

Sustained surface melt that descends to the glacier bed in moulins generally continues to flow down-glacier in pipe-form conduits (Röthlisberger channels), except for during onset of the melt season or early in rapid drainage of surface lakes, when such passageways remain partially closed or disconnected after the winter low-flow period. Do such channels also exist where water derives only from basal melt?

The limited subglacial data from mountain glaciers and ice sheets sourced primarily by subglacial melt indicate conditions incompatible with the vigorous, quasi-steady Röthlisberger channels needed for transporting sediment rapidly. A rapidly-flowing subglacial stream mobilizes and transports sediment in suspension and as bedload (reviewed by Alley and others, Reference Alley1997). Both increase with flow rate, as turbulent eddies keep particles aloft and turbulent bursts impact the bed. The turbulent flow eventually dissipates all its energy as heat, which melts channel walls and lowers water pressure. (For a review, see Cuffey and Paterson, Reference Cuffey and Paterson2010.) Rapid but sustained sediment transport thus is coupled to locally low water pressure. Limited data from boreholes (e.g. Alley and others, Reference Alley, Blankenship, Rooney, Bentley, Waddington and Walder1987; Kamb, Reference Kamb, Alley and Bindschadler2001; Tulaczyk and others, Reference Tulaczyk, Kamb and Engelhardt2008), the widespread existence of subglacial lakes and the very low seismic velocities of till beneath ice sheets (e.g. Christianson and others, Reference Christianson2014; Muto and others, Reference Muto2019) all indicate high basal water pressures, very close to flotation. (We note in passing that models estimating basal lubrication by equating the potential of subglacial water with that of the ocean at the terminus – so-called ‘height above flotation’ models – yield very large errors, up to hundreds of bars, wherever tested against measured water pressures beneath inland parts of ice sheets; Paterson (Reference Paterson1994) wrote ‘…this method of calculating water pressure should be abandoned’ (p. 153), while Cuffey and Paterson (Reference Cuffey and Paterson2010) called it ‘not a physically plausible assumption’ (p. 372).)

Even for the exceptionally high basal melt rates at the head of the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream (>10 cm a−1, driven by geothermal flux exceeding 1 W m−2) (MacGregor and others, Reference MacGregor2016), geophysical evidence indicates basal water pressure close to flotation, consistent with distributed rather than channelized subglacial water flow (Alley and others, Reference Alley2019). Comparison to subaerial conditions helps put this in context. The 10 cm a−1 melting is spread uniformly over the year, generating water fluxes much smaller than peak flows in almost any subaerial fluvial system, where similar or larger annual total fluxes are typically strongly concentrated in time due to episodic precipitation. Because sediment transport increases as approximately the square or cube of water flux above a threshold (see the discussion, with caveats, in Alley and others, Reference Alley1997), sediment fluxes that can be sustained by basal melt are very small, as are the turbulent heat fluxes from dissipation in flowing water that melt ice and lower the water pressure.

In contrast, the channels beneath glaciers with melting upper surfaces can operate with exceptionally high sediment-transport capacity (reviewed by Alley and others, Reference Alley1997), due to: (1) very large water fluxes (often several meters per year to more than 10 m a−1, matching or exceeding the highest subaerial rainfall rates anywhere) generated primarily during episodic hot summer days and rainstorms; (2) the strong spatial localization of flow where moulins deliver water to the bed and (3) the typical steepening of subglacial-stream potential gradients toward the ice front as the ice-air surface steepens toward the terminus. Wading across a proglacial meltwater stream on a hot summer afternoon is not recommended, because it brings the competing risks of being washed away and of having one's ankles crushed by rolling boulders.

The ongoing changes of glaciers, viewed in this context, have important implications for the interpretation of recent sediment fluxes. We will return to this topic after a brief consideration of outburst flooding.

Because of the superlinear increase of sediment transport with water flux, any process that localizes water flow in space or time enhances the ability of that water to transport sediment. One of the major recent advances has been documentation of subglacial lake filling and draining.

Catastrophic subglacial outburst flooding arising in special circumstances has long been known (e.g. Bjornsson, Reference Bjornsson2010). Prolific sediment transport, with erosion and deposition, can occur in such outbursts; the 1996 jokulhlaup triggered by subglacial eruption of the Grimsvotn volcano in Iceland drove tunnel-channel formation and destruction of highway bridges (Russell and others, Reference Russell, Gregory, Large, Fleisher and Harris2007). Geomorphic evidence suggests that very large subglacial outburst floods in Antarctica created channeled-scablands-type landscapes in the past (e.g. Denton and Sugden, Reference Denton and Sugden2005; Alley and others, Reference Alley2006; Larter and others, Reference Larter2019).

Available data, although limited, indicate that the ‘outburst floods’ associated with filling and draining of modern subglacial lakes in Antarctica (e.g. Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Scambos, Bindschadler and Padman2007) are instead slow and geomorphically unimportant. Remote-sensing determinations of elevation change have indicated fill and drain cycles over months to years, but lack of high time resolution in these measurements makes rates poorly known. Seismic observations of migrating harmonic tremor, likely from flood events, indicate that some drainage may occur over hours, but still involving relatively slowly-flowing, small water bodies with fluxes much smaller than major jokulhlaups (Winberry and others, Reference Winberry, Anandakrishnan and Alley2009). The most direct evidence that recently observed Antarctic lake draining and filling did not involve significant sediment fluxes derives from coring into Subglacial Lake Whillans, which revealed that ‘floods must have insufficient energy to erode or transport significant volumes of sediment coarser than silt’ (Hodson and others, Reference Hodson, Powell, Brachfeld, Tulaczyk and Scherer2016). Sedimentary evidence from sidescan sonar, coring and other data sources applied to the continental shelf around Antarctica shows widespread diamicton with little sorted sediment (e.g. Wellner and others, Reference Wellner, Heroy and Anderson2006). The few channels and limited sorted sediment occasionally observed in some diamicton-dominated areas are possibly linked to tidal channels (Horgan and others, Reference Horgan2013). Thus, while the Miocene-age large outburst floods reported by Denton and Sugden (Reference Denton and Sugden2005) significantly impacted the landscape, the recently observed events fed by subglacial melt in Antarctica appear geomorphically unimportant.

Possibly more interesting are drainages to and along the glacier bed from lakes on the ice-sheet surface. In some ablation zones, notably that of the southwestern Greenland ice sheet, flow over rough bedrock creates hollows in the ice-air surface that fill with water during summer. These sometimes drain catastrophically (e.g. Das and others, Reference Das2008), contributing to moulin formation (Alley and others, Reference Alley, Dupont, Parizek and Anandakrishnan2005) and probably influencing subglacial sediment transport. At present, the lake drainages of Greenland tend to be well inland. The water transferred rapidly to the bed forms a lens at the base, which then drains rather slowly, over more than a day (Stevens and others, Reference Stevens2015). Relatively little work has been done on the sedimentological importance of this process, but the lack of immediate connection to high-capacity outlets likely limits the sediment fluxes produced to the local area. (In the lower ablation zone of Greenland, on the other hand, surface melt feeds a system of subglacial tunnels comparable to those beneath mountain glaciers.)

Zoet and others (Reference Zoet, Muto, Rawling and Attig2019) provided evidence that paleo-drainages from supraglacial lakes close to the ice-sheet margin of the Green Bay lobe, Wisconsin, generated efficient connections to the nearby ice margin and eroded extensively, forming tunnel channels (discussed further below). Possible roles for such drainage events in other paleoglaciological settings, perhaps including washing the bed to produce corridors that supply sediment to eskers (Burke and others, Reference Burke, Brennand and Perkins2012), have not been extensively investigated. (Here, we do not further consider eskers and the nature of the drainage feeding them, but progress has been rapid (e.g. Shackleton and others, Reference Shackleton2018; Hewitt and Creyts, Reference Hewitt and Creyts2019), and they surely deserve further attention.)

Apart from settings with outburst floods, the requirement for a concentrated water supply to drive vigorous subglacial streams that remove till cover limits rapid erosion to ablation zones where meltwater reaches the bed. Further limitation arises from processes that subsequently restrict the subglacial streams. As discussed next, two possible restricting factors are adverse bed slopes, of magnitudes up to and including those sufficient to cause supercooling, and backpressure from terminal water bodies.

Overdeepenings

As argued by Hooke (Reference Hooke1991; also see Alley and others, Reference Alley, Lawson, Evenson, Larson and Baker2003), adverse bed slopes on the downglacier sides of overdeepenings may arise from differential erodibility of the bed, but are expected from erosion beneath glaciers even without strong lithologic contrasts. Stretching from flow over a high part of the bed tends to open crevasses at the surface, which preferentially capture surface meltwater and route it to the bed (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1906b), generating water-pressure fluctuations that promote quarrying (see below). This process continues, developing an overdeepening, until the adverse slope out of the overdeepening becomes steep enough to slow or stop the removal of the erosion products, especially by generating supercooling of the subglacial water as discussed next.

Supercooling arises from simple thermodynamics. Subglacial water generally exists at pressures slightly below those of the ice-overburden, and is in contact with ice very close to the equilibrium melting temperature. Because this equilibrium melting temperature increases with decreasing pressure, water flowing toward thinner ice from beneath a glacier must warm to remain liquid. Work done in water flow primarily dissipates as heat, providing a source to warm the water. For beds that slope in the same direction as the ice surface, or are opposed to the surface but with slope magnitude less than ~1.5 times that of the surface, excess heat is generated. The excess heat melts ice, which expands the channel, and yields the water-pressure drop associated with Röthlisberger (R-) channels. For opposed bed slopes with a magnitude >1.5 times the steepness of the surface slope, heat generation is insufficient to maintain the water at the melting temperature, so the water supercools and grows ice. The ice plugs channels, diverting flow out to widespread, distributed flow systems (e.g. Röthlisberger, Reference Röthlisberger1968; Hooke and others, Reference Hooke, Miller and Kohler1988; Alley and others, Reference Alley, Lawson, Evenson, Strasser and Larson1998; Lawson and others, Reference Lawson1998; Creyts and Clarke, Reference Creyts and Clarke2010; Walder, Reference Walder2010).

In the net-melting regime, larger streams generate more heat, and thus drive faster melting and yield lower steady-state water pressures. Smaller streams at higher pressure tend to flow into the larger streams, increasing total sediment-transport capacity (Alley and others, Reference Alley1997). Melting also increases with increasing potential gradient, and so too with the downward bed slope in the ice-surface direction. Reduction and then reversal of that bed slope will reduce subglacial sediment flux even before reaching the supercooling threshold. Hooke (Reference Hooke1984) noted that steep bed slopes in the direction of the ice surface slope can reduce water pressure in R-channels to atmospheric beneath moderately thick ice. Up-glacier extension of such zones toward regions with water pressures close to overburden steepens along-channel gradients farther up-glacier, driving faster water flow and allowing greater sediment transport (Flowers, Reference Flowers2008, Reference Flowers2015). It follows that any reduction in along-flow downward bed slope will reduce the ability of the glacier to evacuate sediment to the proglacial environment. The observations and modeling by Vore and others (Reference Vore, Bartholomaus, Winberry, Walter and Amundson2019) document important aspects of this beneath Taku Glacier, with adverse bed slope causing splitting of subglacial streams, which must reduce the ability to transport sediment because of the superlinear dependence of sediment transport on water flux.

Development of terminal lakes or fjords that raise the outlet pressure of R-channels will also reduce ability of a glacier to vacate sediment. Streams discharging at floating margins face a special difficulty, as the R-channel pressure must be at least slightly above the pressure in the water body to allow discharge, but the R-channel will leak into a distributed system as the channel pressure approaches the ice-overburden pressure. Approach to flotation of the ice terminus thus causes a reduction in transport capacity there. Much literature is relevant to these issues, but they have received perhaps less attention in the sediment-transport literature than warranted.

If vigorous subglacial erosion or proglacial deposition exceeds proglacial downcutting or sediment evacuation for a sufficiently long time, the glacier will form an overdeepening and its bed will approach the supercooling threshold (Hooke, Reference Hooke1991; Alley and others, Reference Alley, Lawson, Evenson, Larson and Baker2003). In the case of bedrock erosion, further overdeepening beyond that threshold is strongly restrained by loss of the ability of subglacial streams to discharge bedload (e.g. Pearce and others, Reference Pearce2003). Physical understanding and limited data thus suggest that geomorphically active glaciers can exhibit stabilizing feedbacks much like those involved in graded rivers (Alley and others, Reference Alley, Lawson, Evenson, Larson and Baker2003). Under steady climate, many and perhaps most geomorphically active glaciers then tend toward ‘grade’ with a little supercooling restricting erosion a little, coupling the subglacial and proglacial environments.

Some possible implications of moulin control

Virtually all glaciers have evolved during the 20th and 21st centuries in response to climate forcing associated with the end of the Little Ice Age and anthropogenic warming (e.g. Zemp and others, Reference Zemp2015). Some glaciers, such as Matanuska Glacier, have experienced slope reduction in the terminal lobe. (This likely is occurring because thinning of ice over a prominent bedrock high has greatly restricted ice inflow to that terminal lobe, somewhat analogous to waning water flow in an ephemeral stream causing evolution from a nearly uniform water-surface slope to a pool-and-riffle pattern and eventually to isolated pools.) In many glaciers, however, frontal retreat has produced steeper surface slopes in the lower ablation zone, though not necessarily right at the terminus (see, e.g. p. 481 of Cuffey and Paterson (Reference Cuffey and Paterson2010)). Given our understanding of the coupling among surface slope, bed slope and sediment transport removing till and enabling erosion, it follows that modern sediment fluxes are nonsteady (see, e.g. Koppes and Hallet, Reference Koppes and Hallet2006).

In the cases, probably few, where response to climate change has shifted the glacier to generate strong supercooling, sediment flux leaving the glacier is reduced. For Matanuska Glacier, much of the Matanuska River bubbles up around the edges of the glacier carrying essentially zero bedload, despite evidence that abundant bedload was discharged during the Little Ice Age (Alley and others, Reference Alley, Lawson, Evenson, Larson and Baker2003). For many other glaciers, however (Hallet and others, Reference Hallet, Hunter and Bogen1996; Koppes and Hallet, Reference Koppes and Hallet2006), recently measured sediment fluxes greatly exceed long-term averages. Total sediment fluxes in regions with retreating glaciers may be enhanced because of paraglacial processes as well as subglacial processes, and those paraglacial processes – unbuttressing of walls allowing landslides, unblocking of tributary streams from nonglaciated regions, even possible triggering of earthquakes that in turn trigger landslides – may be important but are beyond the scope of this review (e.g. Koppes and Hallet, Reference Koppes and Hallet2006; Ballantyne and others, Reference Ballantyne, Wilson, Gheorghiu and Rodés2014; Grämiger and others, Reference Grämiger, Moore, Gischig, Ivy-Ochs and Loew2017; Higman and others, Reference Higman2018). Advancing glaciers can remobilize and transport paraglacial or nonglacial sediments, and retreating glaciers stimulate transport and erosion, so climatic cycling exerts strong influences on erosion rates that have not been greatly explored.

Note that the recent ‘pulse’ of subglacial sediment likely represents both remobilization of stored sediment and bedrock erosion generating new sediment. The steepening of lower ablation zones, shifting them away from the supercooling threshold and increasing sediment transport capacity, has in general been accompanied by increased surface melting supplying more water, and by migration of moulins up-glacier. The latter shifts the zone of moulins over regions of the bed that were previously till-mantled and where erosion was thus slow. Sweeping away this till in up-glacier-extended R-channels adds the stored sediment to the proglacial sediment load, and restarts bedrock erosion.

Physically, these results are well-founded, and sediment fluxes larger than long-term averages are well-documented (Koppes and Hallet, Reference Koppes and Hallet2006). Relatively little work has tracked the locations of moulins reaching the bed, the time-variation in the extent of subglacial till in up-glacier regions, or other aspects of the discussion here, leaving large scope for additional research. How streams migrate to entrain sediment, or how sediment is transported to reach streams, are important topics awaiting further insights. The ability of seismic techniques to track subglacial streams that dominate sediment transport opens a potentially fruitful line of research on these key topics (Vore and others, Reference Vore, Bartholomaus, Winberry, Walter and Amundson2019).

Supercooling, backwater effects of proglacial lakes and oceans, and related processes that reduce sediment flux from geomorphically active glaciers may help explain observations on long-term evolution of major glaciers draining mountain belts (e.g. Shuster and others, Reference Shuster, Cuffey, Sanders and Balco2011; Valla and others, Reference Valla, Shuster and van der Beek2011). In at least some cases, the onset of widespread glaciation led to rapid downcutting well downstream, forming low-elevation and low-gradient valleys or fjords. Downcutting then largely ceased there, with dominance by headward erosion taking over to extend the low-gradient reaches up-glacier. Climatic influences are certainly important – lowering of the glacier surface increases melting – but development of features in the terminal region that inhibited sediment discharge could be important too.

Erosive processes – some recent insights

Subglacial fluvial processes

Subglacial erosion of bedrock occurs primarily by quarrying of blocks (often producing sediment with a cobble-sized mode), by abrasion producing finer-grained material (often with a silt-sized mode), and by subglacial fluvial action. Glaciotectonism can translocate substrate material, as in the formation of hill-hole pairs (e.g. Clayton and Moran, Reference Clayton, Moran and Coates1974; Rise and others, Reference Rise, Bellec, Ottesen, Bøe and Thorsnes2016), but probably does not account for much long-range sediment transport.

Subglacial fluvial erosion (e.g. Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1906b) produces Nye channels incised in rock (Nye, Reference Nye1973). Such features are observed in deglaciated bedrock (e.g. Walder and Hallet, Reference Walder and Hallet1979) but do not dominate such terrain (Fig. 1). At a larger scale, fluvial action creates tunnel valleys (tunnel channels) in both sediment and bedrock (e.g. Booth and Hallet, Reference Booth and Hallet1993; Kehew and others, Reference Kehew, Piotrowski and Jørgensen2012; Atkinson and others, Reference Atkinson, Andriashek and Slattery2013; Kearsey and others, Reference Kearsey, Lee, Finlayson, Garcia-Bajo and Irving2018). Recent work on occurrence and causes of narrow canyons incised into the floors of glacial troughs (‘inner gorges’) in the Swiss Alps and Scandinavia also argues for vigorous and relatively extensive subglacial fluvial erosion (Dürst-Stucki and others, Reference Dürst-Stucki, Schlunegger, Christener, Otto and Götz2012; Jansen and others, Reference Jansen2014; Beaud and others, Reference Beaud, Venditti, Flowers and Koppes2018). As additional geophysical and borehole data have been collected, buried inner gorges have been identified. Modeling suggests that subglacial streams can carve bedrock channels relatively rapidly (e.g. Beaud and others, Reference Beaud, Flowers and Venditti2016).

Fig. 1. Photograph of a Nye channel located in the forefield of Castleguard Glacier, Canada, with annotated inset in lower right. A pocket multi-tool in the middle of the channel near the center of the picture is marked M in the inset. Ice flowed in from upper right to lower left, more-or-less along the purple arrow in the inset, and more-or-less parallel to water flow in the channel, which is shown in blue in the inset. Large areas of the bedrock free of white precipitate existed in subglacial cavities; the floors of two cavities are shown in orange in the inset. Photo by L. Zoet.

Streams are narrow features, such that even rapid incision by them corresponds to very low basin-averaged erosion rates. In a subaerial environment, the downcutting by streams creates lateral slopes that erode by weathering and hillslope transport processes such as landslides and creep. In this manner, the incision by the stream is communicated to the surrounding watershed and the basin-averaged denudation can vary with the rate of stream erosion. In the subglacial case it is not clear how stream incision into bedrock can be communicated laterally to the rest of the basin, and this is a question deserving of research. Where climate cycles cause alternating periods of ice occupation and subaerial terrain, lateral communication may occur via standard watershed processes during the interglacial periods. Where glacial erosion is rapid, the downcutting by subglacial streams would be a trivial factor. An interesting question to investigate concerns the intermediate case: would subglacial erosion by ice and smaller tributary streams increase in response to the downcutting of a rapidly-incising trunk stream?

Pleistocene glaciation typically started in mountainous terrain on steep slopes, allowing highly erosive subglacial streams, and extended as ice sheets advanced across relatively flat land surfaces. Over time, in many places, glacial-geomorphic processes led to subglacial erosion or proglacial deposition faster than in the proglacial environment, and consequently tended to shape the land surface into overdeepenings that reduce the transport capacity of subglacial streams. It may be that subglacial streams are initially more capable and erode subglacial bedrock channels (aided by outburst floods from drainage of supraglacial or ice-dammed lakes in at least some cases). Subsequently, restriction of the streams may allow abrasion and quarrying to ‘catch up’ as streams switch from active bedrock erosion to sediment transport or deposition, or sedimentation during retreat may fill the bedrock channels without eroding them away.

Numerous studies (e.g. Alley, Reference Alley1992; Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994) bear on the mechanisms by which moulin-fed streams interact with subglacial till, enabling transport of the sediment. However, large uncertainties remain. The recent development of seismic techniques to map subglacial stream evolution may provide important new insights (Vore and others, Reference Vore, Bartholomaus, Winberry, Walter and Amundson2019).

Subglacial abrasion and quarrying

Glacial scholars are divided on the question of whether the subglacial removal of blocks of rock should be designated quarrying or plucking. In common English usage, ‘plucking’ specifically refers to a removal process that is rapid; a hair is plucked from an eyebrow or a weed is plucked from a garden's soil. We therefore prefer the term quarrying, which means removal of rock, even though whether the quarrying agent is a person or a glacier may need to be clarified in some contexts.

Our understanding of erosion by abrasion and quarrying rests in important part on the models of Hallet (Reference Hallet1979, Reference Hallet1981, Reference Hallet1996). Although other work before and after has been important, these papers are foundational. Abrasion is primarily achieved by clasts carried in basal ice (for abrasion within and beneath till, see Cuffey and Alley, Reference Cuffey and Alley1996, and Scherer and others, Reference Scherer, Sjunneskog, Iverson and Hooyer2005). Clasts in basal ice contacting the bed are pressed downward by vertical ice flow balancing basal melting and lateral extension, and by their weight in excess of buoyancy provided by the ice. The clasts move forward in the sliding ice, but are partially retarded by friction against the bed, which is in turn overcome by drag as ice flows horizontally around the clasts via enhanced creep and regelation.

For quarrying, concentration of overburden weight or basal shear stress localized near the margins of cavities drives fracturing, and growing fractures can intersect pre-existing structural weaknesses in the rock including bedding planes and joints (Fig. 2). The orientations and spacings of such weaknesses are known to control the locations and orientations of quarried surfaces (Hooyer and others, Reference Hooyer, Cohen and Iverson2012), and to affect strongly the overall rate of quarrying and its importance relative to abrasion (Matthes, Reference Matthes1930; Dühnforth and others, Reference Dühnforth, Anderson, Ward and Stock2010; Krabbendam and Glasser, Reference Krabbendam and Glasser2011). In consolidated rock masses, however, the presence of such weaknesses does not generally allow removal of blocks without additional fracturing; excavation of roadcuts and operation of industrial quarries, for example, usually require blasting and sawing. Thus, for the case of subglacial erosion, we regard the glaciological imposition of concentrated loads and their ability to drive fracture growth as paramount. How this process interacts with pre-existing weaknesses is a question deserving full analysis (see Iverson, Reference Iverson2012; Woodard and others, Reference Woodard, Zoet, Iverson and Helanow2019). It is also doubtless true that in some landscapes, where episodic ice occupation occurs during a minority fraction of glacial climate cycles, erosion occurs primarily by subaerial weathering during interglacial periods followed by glaciers sweeping away the resulting unconsolidated mantle (Sugden and John, Reference Sugden and John1976). In such a situation, neither abrasion nor quarrying needs to be rate-controlled by the glaciologic factors highlighted here.

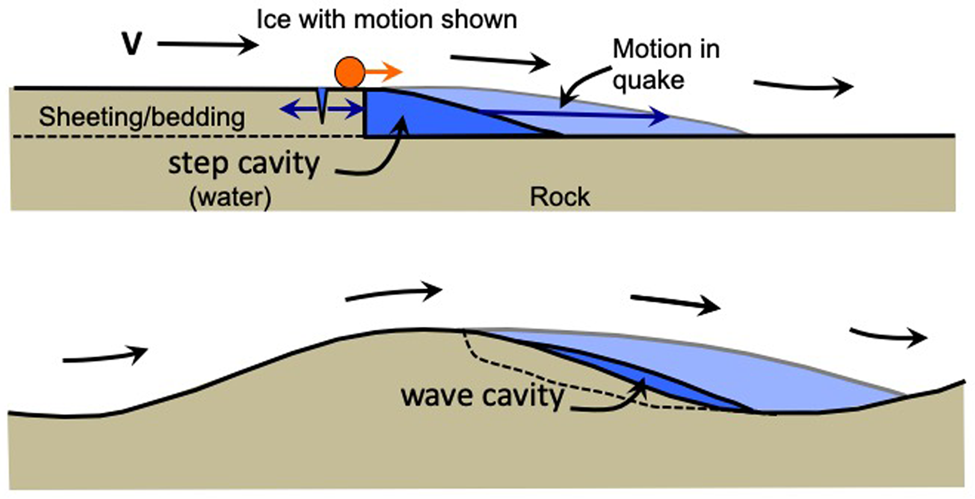

Fig. 2. Diagram of some processes involved in bedrock erosion by glaciers, from Zoet and others (Reference Zoet, Alley, Anandakrishnan and Christianson2013a) (used with permission). An abrading clast is shown in orange in the upper panel. During transient acceleration of basal motion, especially during basal earthquakes, water-filled lee-side cavities (dark blue) expand (light blue), lowering water pressure in the cavities while leaving high water pressure in cracks and pores, and focusing stress from the ice and its abrading clasts on the remaining regions of ice–bed-contact, favoring crack growth and quarrying. In the presence of bedding or sheeting joints (upper panel), this causes up-glacier migration of the bedrock step. For a wave cavity (lower panel), a possible failure pattern is sketched, tending to increase lee-side relief.

Several constraints indicate that quarrying is generally more important than abrasion in erosion (e.g. Zoet and others, Reference Zoet, Alley, Anandakrishnan and Christianson2013a). This follows despite the dominant role of abrasion in producing arguably the most distinctively glacial features, providing photogenic, smooth surfaces with striae and glacial polish (Siman-Tov and others, Reference Siman-Tov, Stock, Brodsky and White2017) (Figs 3 and 4), sometimes also marked with crescentic gouges and crescentic fractures related to the episodic movement of large clasts (e.g. Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1906a). Except in deep mountain valleys, most of the sediment discharged from beneath glaciers is generated from their beds (e.g. Alley and others, Reference Alley1997). Typically, a wide range of grain sizes is present, but with dominance by silt from abrasion and cobbles from quarrying. Available data (e.g. Gurnell and Clark, Reference Gurnell and Clark1987) suggest that these are subequal in most cases, but some of the silt derives from abrasion of the cobbles themselves, which typically display facets and striae. Hence, quarrying achieves a substantial majority of the erosion. Furthermore, quarrying is likely to be rate-limiting, because plucked clasts provide most of the tools for abrasion, except possibly in rugged mountains where rockfalls and landslides descend large headwalls into the head of the glacier.

Fig. 3. Limestone bedrock in the forefield of Tsanfleuron Glacier, Switzerland. Ice flow was from left to right. Left half of the bed obstacle was smoothed by abrasion while step on the right side of the obstacle was excavated by quarrying. Hand-held GPS instrument for scale. Photo by L. Zoet.

Fig. 4. Granitic bedrock in the forefield of Rhone Glacier, Switzerland. Ice flow was from left to right. Smooth section on the left of the picture was abraded, while the steep step on the right side of the picture results from glacial quarrying. Many similar features are visible in the background. The figure spans ~10 m across the photo. Photo by L. Zoet.

Of the many advances in understanding quarrying and abrasion, we highlight a few here. First, observations made from a subglacial laboratory beneath Engabreen, Norway indicate surprisingly large friction between debris-bearing ice and subglacial bedrock (Iverson and others, Reference Iverson2003; Cohen and others, Reference Cohen2005). This has motivated laboratory experiments (e.g. Byers and others, Reference Byers, Cohen and Iverson2012; Zoet and others, Reference Zoet2013b), which have clarified the situation and broadly confirmed the accuracy of prior models for ice–clast interactions, but which leave unsolved the problem of how the large observed friction arises. Further work is needed. This topic is especially important because it affects not just erosion and the stresses contributing to quarrying, but also the occurrence of basal earthquakes and the basal ‘flow law’ for ice-sheet modeling.

Progress has been made in understanding quarrying, as well, and its importance for glacial landscapes (e.g. Iverson, Reference Iverson2012; Anderson, Reference Anderson2014). Here we highlight the role of fluctuations in driving quarrying (e.g. Hooke, Reference Hooke1991; Iverson, Reference Iverson1991; Cohen and others, Reference Cohen, Hooyer, Iverson, Thomason and Jackson2006; Ugelvig and others, Reference Ugelvig, Egholm, Anderson and Iverson2018). Transiently high water pressure expands cavities (Andrews and others, Reference Andrews2014), focusing the basal shear stress and overburden weight on smaller regions of the bedrock. Subsequent rapid declines of water pressure increase the quarrying stresses by reducing the water pressure that had ‘buttressed’ bedrock steps from their lee sides and supported the overburden. The nonlinear nature of fracture propagation implies that such temporary focusing of stresses can completely dominate the quarrying process (Hallet, Reference Hallet1996). Long-term maintenance of either exceptionally high or exceptionally low water pressure is unlikely because of negative feedbacks in the evolution of the water system. Transient highs in water pressure will increase cavitation and hence transmission of water, reducing pressure, whereas transiently low pressures will slow sliding and accelerate cavity closure, reducing cavity aperture and water transmission, thus raising water pressures. Furthermore, the surface speed and surface slope will adjust in response to changed basal lubrication, with sustained high water pressure ultimately reducing basal shear stress by thinning the ice or reducing the surface slope.

Thicker ice can generate larger fluctuations in the subglacial water system and associated focused loading on the bed around cavities, providing a mechanism that increases erosion rate under thicker ice, as discussed next. With the exception of short-lived, exceptionally large pressure pulses observed beneath a soft-bedded glacier (Kavanaugh and Clarke, Reference Kavanaugh and Clarke2000), documented subglacial water pressures generally range from slightly above the weight of the ice (flotation) down to zero, a difference that increases with ice thickness. In the absence of such fluctuations, ice thickness does not directly enter most prior models for erosion, as discussed above. (Ice thickness does enter indirectly through its influence on driving stress, and hence ice velocity.) As typically modeled (Hallet, Reference Hallet1996; Iverson, Reference Iverson2012) the influence of thickness is limited somewhat by the crushing strength of ice, because ice–rock contact stresses adjacent to cavities are assumed to plateau as ice fails. However, with sufficient englacial debris or with sufficiently fast fluctuations, this limitation may not be strong; additional consideration seems warranted.

The influence of ice thickness may be especially important in basal earthquakes. As seismic instrumentation and deployment have improved, observations of basal earthquakes beneath glaciers and ice sheets have become almost routine. Zoet and others (Reference Zoet, Alley, Anandakrishnan and Christianson2013a) summarized observations from four sites for which source parameters could be estimated from the data, finding typical slip of order 1 mm over order 0.01 s. Zoet and others (Reference Zoet, Alley, Anandakrishnan and Christianson2013a) then calculated that this motion would drop the pressure in typical lee-side subglacial cavities to or near zero, while water pressure in pores or cracks in adjacent rock remained near the overburden pressure. This would increase the crack-driving stresses in the rock, perhaps greatly, and contribute to quarrying. To the best of our knowledge, no data actually resolve the seismic radiation from quake-triggered crack growth, which likely would be quite small compared to the originating quake and thus difficult to observe. But, it seems likely that this process does contribute to erosion, perhaps greatly, and that this is one specific pathway for thicker ice to erode faster.

A second result from Zoet and others (Reference Zoet, Alley, Anandakrishnan and Christianson2013a) addresses the geometry of the cavities. For lee-side cavities behind down-steps in the bedrock, quarrying will tend to shift the steps up-glacier. However, if the bed undulates smoothly (picture a sinusoid) instead of in steps, water will tend to form wave-cavities (Kamb, Reference Kamb1987), extending along the gradually sloping bed in the lee of bedrock high-points. Sudden expansion of such cavities from an earthquake will favor generation of steeper up-glacier sides of cavities through quarrying, producing steps on bedrock otherwise lacking preexisting jointing or bedding with high-angle intersections (Fig. 2).

Predictive models of occurrence of subglacial earthquakes are still lacking, so this process would be difficult to calibrate in erosion models. Nonetheless, physical understanding indicates that earthquake-driven erosion likely occurs, and it may be important or even dominant, motivating additional studies. A similar set of arguments applies to the extreme pressure pulses identified by Kavanaugh and Clarke (Reference Kavanaugh and Clarke2000) and Kavanaugh (Reference Kavanaugh2009), perhaps also a manifestation of glacier-bed seismicity, where bedrock knobs contact the glacier sole amidst an otherwise deformable bed.

Cirques

In fundamental respects, cirque glaciers are similar to other glaciers, with active ice deformation, hydrological systems and subglacial erosion (Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, MacGregor, Kavanaugh and Dow2010, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, MacGregor and Collins2013; Dow and others, Reference Dow, Kavanaugh, Sanders, Cuffey and Macgregor2011). They flow rather than rotate rigidly, as is sometimes believed, although very thin remnant ice masses might behave that way.

The distinguishing feature of cirque evolution, as opposed to geomorphic effects of other glaciers, is retreat of the headwall, typically into higher topography in a mountain range. Subglacial erosion beneath non-cirque regions of glaciers can be concentrated on steeper slopes, as discussed above, but typically involves more downcutting than horizontal erosion, whereas cirque headwall retreat is primarily horizontal. Headward erosion by cirques is important, for example, in mountain-belt evolution and divide migration, sediment yields from mountain drainage basins, and in paleoclimatic reconstruction (e.g. Brocklehurst and Whipple, Reference Brocklehurst and Whipple2004, Reference Brocklehurst and Whipple2007; Oskin and Burbank, Reference Oskin and Burbank2005; Anders and others, Reference Anders, Mitchell and Tomkin2010; Barr and Spagnolo, Reference Barr and Spagnolo2015).

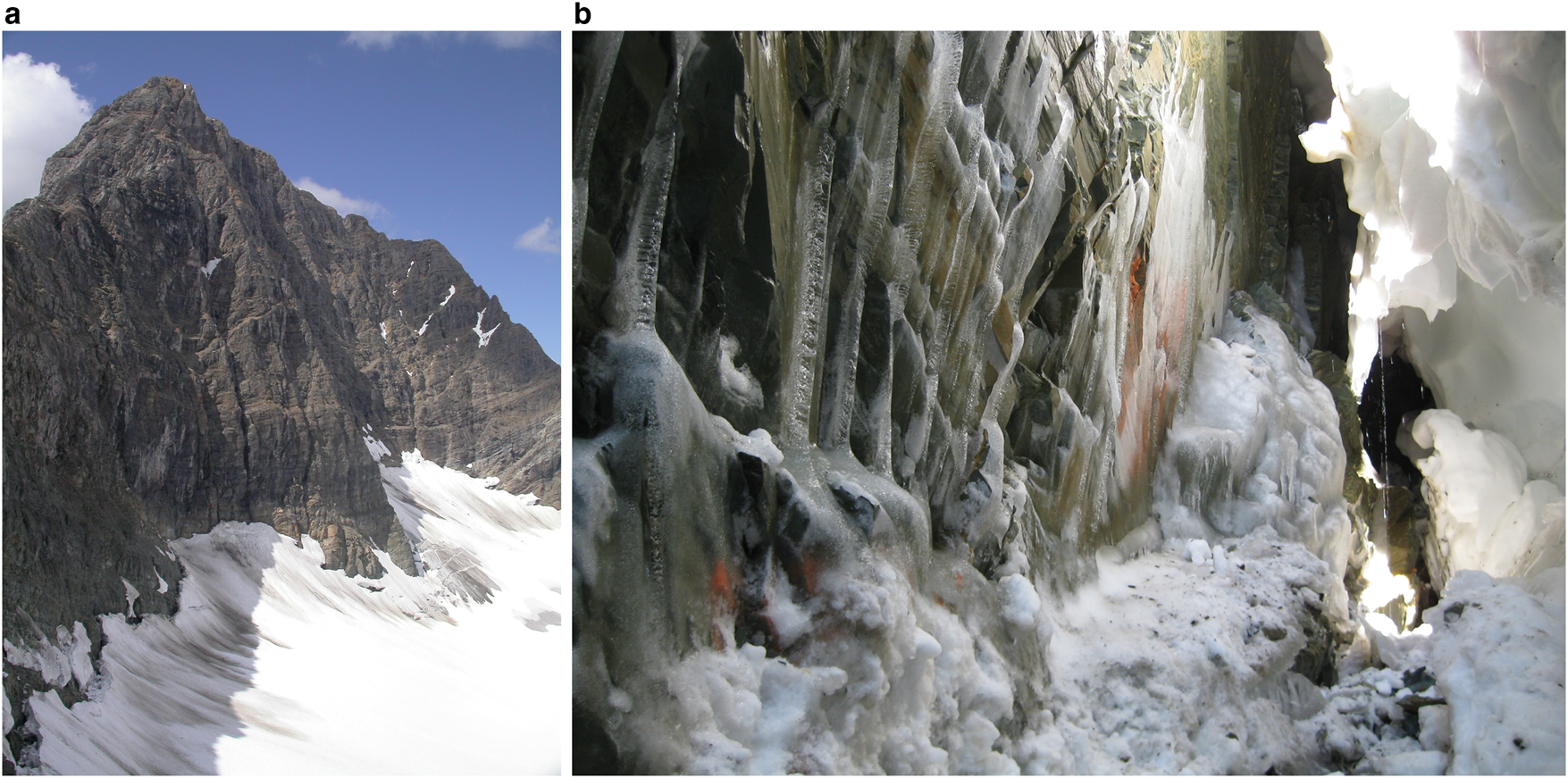

Glacier flow pulls ice away from a cirque headwall, forming a large crack, the bergschrund (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1904; Johnson, Reference Johnson1904; Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012) (Fig. 5). If the top of the bergschrund is sufficiently open, cold air sinks into it during the onset of winter, chilling the rock of the headwall to well below the bulk freezing temperature of water (Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012). During summer, water flows into the bergschrund and air partially mixes with the atmosphere, both warming the surface of the headwall, which in turn warms rock farther behind the surface. The presence of abundant water means that preexisting cracks or joints in the headwall will be water- or ice-filled from prior years.

Fig. 5. Forms and features related to headward erosion of cirques. (a) The towering, oversteepened headwall of Helmet Mountain Cirque in the Canadian Rockies (Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012), showing bergschrund openings along the glacier edges and abundant rockfall debris on the adjacent snowy glacier slopes. Photo by K. Cuffey. (b) The view at 9 m depth in a bergschrund at Helmet Mountain Cirque, showing the bedrock wall on the left, partially mantled with refrozen water, and the glacier on the right. Rock fragments in snow filling the gap are derived both from the exposed cliffs above and the bedrock side of the bergschrund, and are swept down by avalanches and rockfalls. Photo by J. Webb Sanders.

Physical understanding shows that this is an optimal situation for frost-cracking (e.g. Walder and Hallet, Reference Walder and Hallet1985; Dash and others, Reference Dash, Rempel and Wettlaufer2006; Hales and Roering, Reference Hales and Roering2007; Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012). The seasonal cycling of temperature, with strong wintertime cooling, generates steep temperature gradients in the rock with mean conditions below the bulk melting temperature. A pseudo-liquid layer exists between ice and rock, and is thicker where warmer. Thermomolecular pressure along the pseudo-liquid layer drives mass flux down the temperature gradient, feeding growing ice lenses and wedging cracks open. This process operates on a large scale in soils and is known as heave. Once crack growth by this process frees a block from bedrock, volumetric expansion of water on freezing can help quarry the block (Matsuoka and Murton, Reference Matsuoka and Murton2008; Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012). The role of the glacier is twofold: first, to generate the bergschrund, which permits temperature variations favorable for frost-cracking and freeze-thaw processes by circumventing the thermal insulation that normally operates below the glacier surface; and second, to transport blocks freed by these processes, preventing formation of a talus accumulation that would damp temperature fluctuations. This entrainment process may be assisted by avalanches originating on the headwall that sweep into the bergschrund and denude the fractured surface.

Erosion at the level of the bergschrund undermines the overlying headwall. The increased slope facilitates failure of the rock mass, also already weakened by frost-cracking (Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012), and leads to downslope movement by rockfall, landslide and debris flow. Much of the headwall part of the cirque landform therefore manifests the combined action of weathering and hillslope transport rather than the direct action of ice.

Synopsis

Understanding of glacial geomorphic systems is growing rapidly, as new field and laboratory observations inform improved models. The greatest difficulties may arise from the fantastic variability and complexity of glacial systems; no generalization will be true in all contexts, and our review should be accepted in this spirit. Over the >30 million years of Antarctic glaciation (e.g. Pagani and others, Reference Pagani2011), an erosion rate of just 0.01 mm a−1 would have removed more than 300 m or rock. Over such timescales, sediment transport by deforming till or in basal ice can be highly important and must be considered (e.g. Alley and others, Reference Alley, Blankenship, Rooney, Bentley, Waddington and Walder1987; Clark and Pollard, Reference Clark and Pollard1998). We have focused here on the processes involved in the much faster erosion responsible for features such as extensive fjords and other deeply incised glaciated mountain valleys, as well as cirques that have eroded headward over long distances.

In common with all other material-shaping operations including ice-core drilling and much of carpentry, sustained rapid erosion requires removal of the swarf or chips generated. For glacier erosion, some transport in the ice usually occurs, but rapid bedrock erosion in excess of the ability of the ice to entrain debris can quickly generate a lubricating till layer that slows further bedrock erosion and transport. A characteristic rapid subglacial erosion rate of a few millimeters per year would, if entrainment and transport are ineffective, mantle the glacier bed with meters of debris in only a millennium. Again in common with most other material-shaping operations, a ‘working fluid’ is then required to remove the chips; for glaciers, we argue that vigorous subglacial streams fulfill this role. Outburst floods, especially those driven by drainage events from supraglacial lakes near the ice margin, may transport large volumes of sediment, but in general sediment transport is dominated by subglacial streams fed by moulins draining from the surface. Large uncertainties remain about how subglacial streams access widespread sediment, or how sediment is transported to subglacial streams.

Such streams are influenced by the bed slope as well as by the surface slope, water supply and other factors. Sediment-transport capacity is highest on beds that slope downward in the direction of the surface slope and ice flow. If the bed is rotated toward or through horizontal, transport capacity is reduced, and bedload transport is almost entirely stopped for sufficiently large adverse bed slopes. At and beyond the supercooling threshold (bed slope opposed to and more than ~1.5× the surface-slope magnitude), ice grows in subglacial streams and freezes them closed, forcing water to find other paths (e.g. englacial) or to drain out of the channels into a distributed basal system with low transport capacity. Bed-load transport is also limited by high water pressures in proglacial lakes or ocean, which raise the outlet water potential and thus reduce potential gradients driving water flow along subglacial streams.

Wet-based, vigorous glaciers that flow beyond steep upper mountain valleys can erode bedrock much faster than equivalent fluvial or submarine systems. This causes larger glaciers that reach the trunk valleys and flanks of mountain ranges or adjacent lowlands to downcut their terminal regions to or below the proglacial outlet, aided by deposition of moraines at the glacier terminus. This transforms down-sloping bedrock to horizontal or overdeepened beds that may end in deep water, and thus limit further erosion. Glacial downcutting is surely limited by climate – increasing warmth with decreasing elevation eventually melts ice – but likely also is limited by these geomorphic feedbacks that limit sediment evacuation. This favors the observed history of Pleistocene erosion in cases (e.g. Shuster and others, Reference Shuster, Cuffey, Sanders and Balco2011) in which onset of glaciation initially caused rapid downcutting of lower trunk valleys, followed by near cessation of erosion in these regions while steep regions farther up-glacier continue to erode headward to the drainage divide. This pattern also is consistent with emerging evidence that major tidewater outlets flowing in overdeepened fjords of the Greenland ice sheet are well-lubricated (e.g. Joughin and others, Reference Joughin2012; Shapero and others, Reference Shapero, Joughin I, Poinar, Morlighem and Gillet-Chaulet2016) because they are till-floored (Block and Bell, Reference Block and Bell2011; Dow and others, Reference Dow2013; Walter and others, Reference Walter, Chaput and Lüthi2014).

Glaciers erode bedrock through the combined action of abrasion, quarrying and direct fluvial incision. Emerging evidence suggests that fluvial action may be more important in some settings than previously recognized. Difficulty in documenting this may arise in part from the evolution of glacial valleys. Initially vigorous streams may erode bedrock, but at a declining rate as the terminal reach cuts down below base level and flattens or overdeepens, reducing excess transport capacity that allowed fluvial erosion. This may allow quarrying and abrasion to ‘catch up’ with fluvial erosion, erasing the fluvial channels; if not, those channels may be buried by subsequent sedimentation. These speculations are not well-tested yet.

Progress understanding abrasion and quarrying has been substantial. The processes are tightly coupled, with quarrying generally providing the tools for abrasion, and the abrading clasts providing some of the stress that drives quarrying. Because basal friction from abrading clasts is important in basal flow laws and basal earthquake generation as well as abrasion and quarrying, progress in this area is particularly important for the broader glaciological community. Laboratory and field studies are helping explain the results of Cohen and others (Reference Cohen2005) showing surprisingly large basal drag of englacial clasts over bedrock, but many important questions remain.

Several recent studies have reemphasized the importance of fluctuations in water pressure and other controlling variables in driving erosion. In turn, fluctuations likely increase with water supply, but in ways that are not yet fully characterized. And, fluctuations are especially large in subglacial earthquakes, which may be central in subglacial erosion; however, this hypothesis has not been tested extensively.

Many erosional processes depend in some way on ice sliding velocity. Faster ice flow drags more abrading clasts over a bedrock region in unit time, for example, and generates more frictional heat that melts the basal ice faster, causing faster downward ice motion that pushes clasts into the bed more strongly to increase abrasion. Faster ice flow also gives longer lee-side cavities, focusing stresses more strongly on the remaining regions of ice–bedrock contact and thus favoring quarrying. Many models have parameterized glacier erosion in terms of velocity, and have provided insights into important processes. We note, though, that the typical parameterizations for mountain glaciation would, if applied to fast-flowing outlets of the East Antarctic ice sheet over its full history, yield erosion well into the mantle or even into the outer core by now; a velocity-linked law may be applicable there (Clark and Pollard, Reference Clark and Pollard1998; Pollard and DeConto, Reference Pollard and DeConto2020), but with very different physics and rates. There may in fact be an inverse relation between velocity and erosion under many circumstances, with till serving both to speed basal flow and suppress erosion, compared to ice–bedrock contact.

Physical understanding of subglacial erosion, including the importance of removing the swarf/till, leads to expectation of strong time-variation in erosion and transport, and this is consistent with the available data. We note, though, that many aspects of this extended hypothesis are not yet well-observed, so notable uncertainties remain.

During advance, which usually but not always is driven by cooling, ice may extend over proglacial sediments and remobilize them very rapidly (observed to 3 m a−1 beneath Taku Glacier; Nolan and others, Reference Nolan, Motyka, Echelmeyer and Trabant1995), potentially reaching bedrock and starting new erosion. During extended cold, though, subglacial erosion and proglacial deposition faster than proglacial erosion can move the ice to an overdeepened configuration on the threshold of supercooling, giving a ‘graded’ behavior akin to rivers and coupling the glacial geomorphology to the slower proglacial evolution. Erosion can still continue up-glacier on regions of steep downsloping bed reached by moulins, which may or may not be extensive depending on climate and history.

Warming occasionally causes approach to terminal-lobe stagnation as at Matanuska Glacier, which may suppress sediment flux, but in general warming will greatly increase sediment flux. Terminal retreat usually steepens the ice surface of the lower ablation zone, moving away from the supercooling threshold and increasing sediment transport capacity. Moulins also migrate inland over till-mantled regions, remobilizing stored sediment and exposing bedrock for renewed erosion. Additional paraglacial processes, such as landslides following unbuttressing by the retreating ice, can further increase the sediment flux. Almost all contemporaneous observations of glacial sediment flux have been collected during times of retreat, strongly biasing the observed rates and processes compared to long-term averages (Koppes and Montgomery, Reference Koppes and Montgomery2009). Much higher sediment yields observed during the ongoing retreat than long-term averages, the ability of advancing glaciers to remobilize proglacial sediments, and other considerations point to a major role for climate cycling in driving long-term erosion rates; further exploration of this topic could be useful.

Sufficient warming may drive retreat into cirques, where headwall erosion continues by frost-cracking, while subglacial erosion lowers the floor of the cirque by quarrying, abrasion and streams. Climate also influences the headwall erosion, through snow bridging of bergschrund cracks damping temperature fluctuations or meltwater access, climate change affecting mean temperatures and fluctuation magnitudes, and in other ways (Sanders and others, Reference Sanders, Cuffey, Moore, MacGregor and Kavanaugh2012). Paraglacial processes affecting headwall erosion above glacier surfaces are also important.

We recognize that more than 140 citations here leave much of the literature unsampled, and provide only an idiosyncratic view of the whole field. The rate of progress is impressive indeed. Additional focused work may improve understanding of mountain-belt evolution, glacial stability and future changes at the sea level in response to climate change. The growing synthesis of laboratory and field studies with physical modeling, enabling testing using prognostic models, promises rapid progress.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following funding sources for support of this work: US National Science Foundation Division of Polar Programs grant PLR1738934 (RBA); US National Science Foundation Division of Earth Sciences Program grant EAR166104 (LKZ) and The Martin Family Foundation (KMC). We thank numerous colleagues over decades for insights. This manuscript grew out of an invited presentation to the International Glaciological Society (IGS) Symposium on Glacial Erosion and Sedimentation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 12–17 May 2019. LKZ was chair of the local organizing committee; RBA and KMC thank him, the other organizers, and the IGS. The manuscript benefitted from helpful comments by an anonymous reviewer and Maarten Krabbendam.