INTRODUCTION

While improvements in healthcare have resulted in many children with complex and life-threatening conditions living longer (Feudtner et al., Reference Feudtner, Kang and Hexem2011; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Lidstone and Miller2014), a significant proportion of them still die. Worldwide, the largest number of children who need palliative care die from congenital abnormalities, neonatal conditions, or malnutrition. Other conditions include meningitis, HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular disease, endocrine/blood/immune disorders, cancer, and neurological disorders (Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and the World Health Organization, 2014). These children, if not cured, tend to decline in health over a period of months to years, and hence are potential beneficiaries of support from palliative care teams. Palliative care for children is defined as “active total care of the child's body, mind, and spirit, and also involves giving support to the family.” While it is defined as beginning when the illness is diagnosed and “continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease” (World Health Organization, 1998; 2017), in this report we focus on parents who are knowingly faced with their child's decline and eventual death and thus represents the point at which they have to actively cope with the fact that their child is expected to die. While parental adjustment to having a child with a chronic illness (e.g., Woolf et al., Reference Woolf, Muscara and Anderson2016) or bereavement (e.g., Price & Jones, Reference Price and Jones2015) is well-described, there is a paucity of data on adjustment and coping strategies for parents as their child is between these two states: declining and facing eventual death.

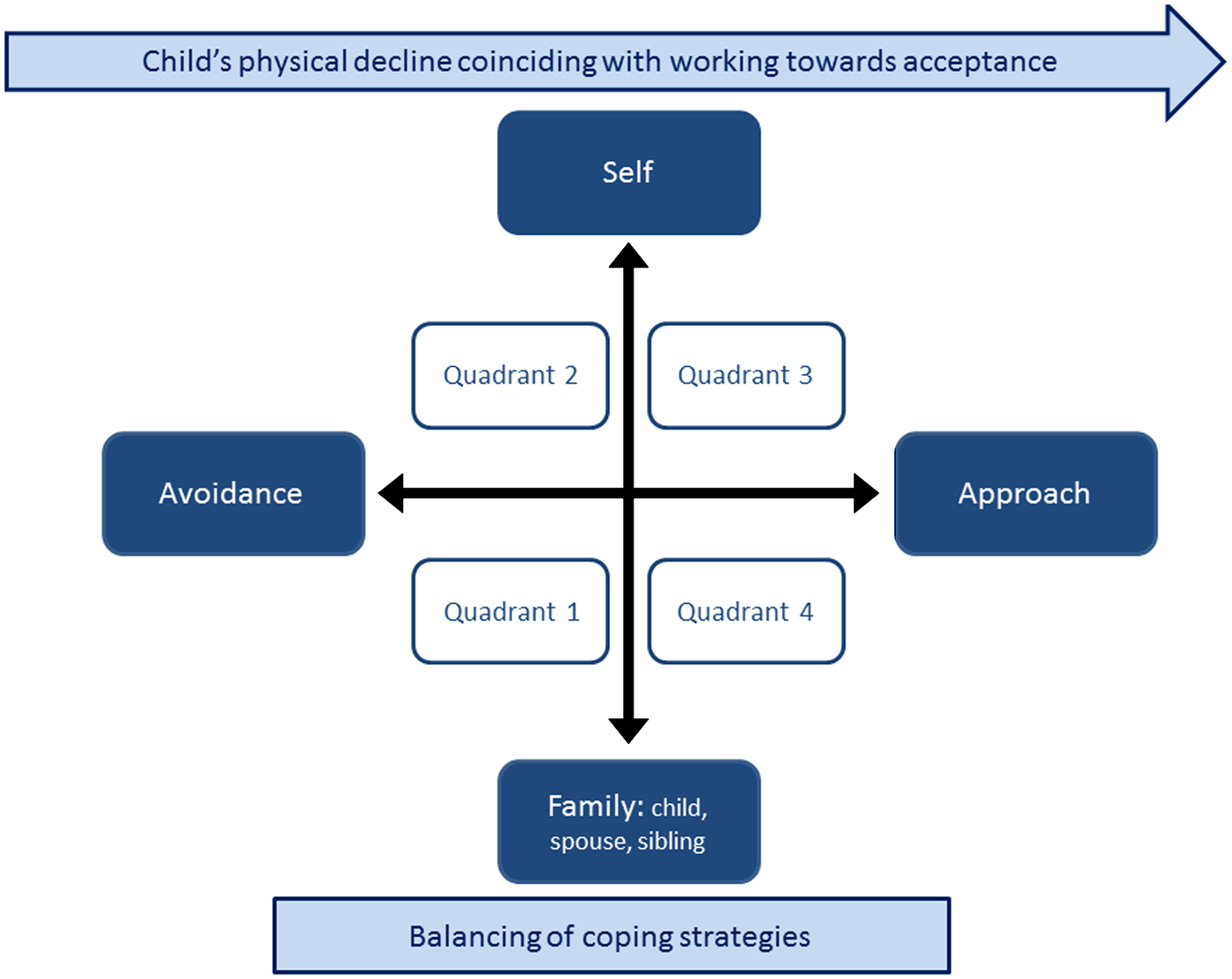

In this paper, we introduce a new theoretical framework (see Figure 1) of coping for parents who have been told that their child will die. We will first discuss the emotional impact on families when caring for a terminally ill child and then detail this framework, along with a vignette that illustrates parental coping with a dying child that aligns with the proposed model. This framework will be able to inform and identify targets for future intervention testing to support families in their ongoing adjustment. Central to the proposed theoretical framework is that effective coping, in terms of adjustment, is achieved by balancing coping strategies. The framework provides a specific focus on (1) approach and avoidance and (2) coping aimed at self and others. Central to this model is the hypothesis that accessing these various coping strategies simultaneously or in parallel aids adjustment to this life-changing event.

Fig. 1. Parental coping theoretical framework.

THE EMOTIONAL IMPACT OF CARING FOR A TERMINALLY ILL CHILD

As a parent, caring for a child with a life-limiting illness is complex and encompasses nursing, technical, and emotional tasks, alongside routine childcare (Young et al., Reference Young, Dixon-Woods and Findlay2002). Throughout the course of such a child's illness, parents have to manage the child's medical treatment, communicate with health professionals, suffer disruption in their role within the family, disruption in their routines, and deal with financial implications, all the while confronting, most importantly, the eventual death of their child (Gerhardt et al., Reference Gerhardt, Baughcum, Young-Salame, Roberts and Steele2009).

The death of a child is considered the ultimate loss (Wilson, Reference Wilson1999), one that challenges the order of life events and the meaning of life (Bogensperger & Lueger-Schuster, Reference Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster2014). Bereaved parents are at risk for anxiety and depression (Dyregrov & Dyregrov, Reference Dyregrov and Dyregrov1999; Hendrickson, Reference Hendrickson2009; Kreicbergs et al., Reference Kreicbergs, Valdimarsdottir and Onelov2004; Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Baker and Syrjala2012), complicated grief (Middleton et al., Reference Middleton, Raphael and Burnett1998; Sanders, Reference Sanders1979), and even mortality (Li et al., Reference Li, Precht and Mortenson2003). Their adjustment and the associated parenting also influences the adjustment of the child and any other siblings (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Gabert-Quillen and Friebert2016).

COPING WITH IMPENDING LOSS

Supporting parents in understanding and exploring their emotions in the face of the possible death of a child should be considered an integral part of professional practice (Penman & Ellis, Reference Penman and Ellis2015). Increasing our understanding of coping strategies that parents employ under such extreme circumstances will increase our understanding of how to best provide support to families, in turn ensuring improved outcomes before and after a child's death (Stroebe & Boerner, Reference Stroebe and Boerner2015).

There is evidence of the importance of considering the context in which demands are made in terms of coping (e.g., De Faye et al., Reference De Faye, Wilson and Chater2006), with different threats making different demands on people. The parents of a child with a life-limiting illness face multiple specific threats that are coupled with and overshadowed by the unique threat of impending death. High levels of stress can disrupt and overwhelm regulatory processes (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2006), and the threat of the child's death requires unique coping behaviors and cognition in order to bring about manageable adjustments.

In clinical practice, a tension can exist between the coping strategies expected and preferred by health professionals and those that parents adopt (Brown & Warr, Reference Brown and Warr2007), as well as between parents' expressed emotions and their actual well-being (Hexem et al., Reference Hexem, Miller and Carroll2013). Understanding coping strategies is important, as such strategies are amenable to psychosocial interventions and therefore present an opportunity to support parents and families, as well as guide predeath risk identification (Bennett & Hopper, Reference Bennett and Hopper2010; Stroebe & Boerner, Reference Stroebe and Boerner2015).

In this report, we will set out a framework to describe parental coping in the context of having a child with a life-limiting illness who is declining and facing eventual death.

MEANING MAKING AND ACCEPTANCE

Such a traumatic event as finding out that your child is likely to die will disrupt a person's assumptive world, thus their sense of order and sense of control (Pakenham, Reference Pakenham2008; Reference Pakenham and Folkman2010). The disruption of parents' assumptive world requires them (in the context of the family) to try to make sense of the world by developing new views and modifying existing schemas (Pakenham, Reference Pakenham2008) in an attempt to gain control and search for meaning (Taylor, Reference Taylor1983).

In trying to make sense of the world, people will create a narrative, for example, by contextualizing the illness and imminent death in the unseen or the spiritual, or revise values, goals, and priorities in view of what is happening (Pakenham, Reference Pakenham2008). Achieving this sense-making is a gradual process. Parents who have been given the news that their child will not survive need to work toward this sense-making as the child's physical health deteriorates. While this is a complex process, the child and family can be described as being on a journey to accept the reality of death, and the health professionals can provide emphatic or compassionate support to enable the patient to follow the path of acceptance (which in most cases is the path naturally chosen; Zimmermann, Reference Zimmermann2004).

While acceptance can be viewed as a coping strategy in itself, coping as described in this manuscript will sit in the context of parents attempting to create a narrative around what is happening to their child while working toward accepting that their child will die.

PROPOSED THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The central premise of the proposed theoretical framework is that, as a parent is confronted with the child's deteriorating physical well-being and approaching death, coping strategies are used that are unique to the context. Extreme loss and extreme emotions of anguish are central elements. This requires enormous cognitive and emotional effort and leads to the first important component of the model—namely, the importance of avoidance or respite from these emotions in order to function. Approach and avoidance, which have been described in the coping literature (e.g., Moos & Schaefer, Reference Moos, Schaefer, Goldberger and Breznitz1993) may thus be especially functional as the child declines. The second important component is the fact that parents have to cope in the context of the relationship with their child and other family members. The attachment to the child leads parents to want to protect and nurture (Kearney & Byrne, Reference Kearney and Byrne2015). This can lead to multiple tensions in light of their own well-being and coping in light of the child's well-being and the integrity of the family system. This highlights the importance of roles within the family and their influence on coping strategies. We propose that effective coping is characterized by balancing between avoidance and approach-related coping strategies, as well as balancing coping strategies that are aimed at achieving well-being for the parent and well-being for the child, and the family system. While these coping strategies are likely to be intertwined, it is helpful to delineate their function in order to highlight and test whether a disbalance in this system will lead to dysregulation and increased difficulties in terms of adjustment. We hypothesize that this balancing process occurs while parents, in time, try to explain and make sense of the child's impending death and work toward acceptance of this possibility.

We will go on to describe the reasoning and argument, as evidenced by current literature, leading to the proposed theoretical framework. In addition, the framework will be illustrated by descriptions of coping strategies in each of the quadrants and accompanying clinical vignettes.

COPING

Coping is a complex multidimensional process that sits under the umbrella of self-regulation (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, Wolchik and Sandler1997), and is essential when adapting to stressful events. It is influenced by the environment (demands and resources) and by personal dispositions. Effective regulation of emotion is essential for adaptive functioning when people are confronted with a significant stressor. Lazarus and Folkman outlined a stress-coping model several decades ago, defining coping as the management of internal and/or external demands that exceed a person's resources. Coping includes both cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage the demands (Folkman & Moskowitz, Reference Folkman and Moskowitz2004; Lazarus, Reference Lazarus1999; Reference Lazarus2006; Lazarus & Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984). Major types of coping strategies have been identified, such as problem-oriented coping, emotional-focused coping, avoidance-oriented coping, and distraction (Folkman & Moskowitz, Reference Folkman and Moskowitz2004).

Child and family adaptation in the context of chronic illness is influenced by numerous factors, including illness-related factors, siblings, parental mental health issues, and social support, as described by several frameworks of family adaptation (e.g., Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; McCubbin & McCubbin, Reference McCubbin, McCubbin and Danielson1989). It is important to take the situational characteristics into account when assessing coping strategies, and it can therefore be appropriate to tailor coping responses to the context (De Ridder, Reference De Ridder1997). In the context of having a child with a chronic illness, parents engage in such coping strategies as maintaining family integration, seeking and maintaining social support, optimistic definition of the situation, and searching for spiritual meaning (e.g., McCubbin et al., Reference McCubbin, McCubbin and Patterson1983). While there will be significant relevance of these domains as a chronically ill child nears the end of his/her life, it is likely that other domains become increasingly important in the context of the possibility of death.

Approach and Avoidance

Coping research has highlighted approach versus avoidance as a classification or description of coping (e.g., Moos & Schaefer, Reference Moos, Schaefer, Goldberger and Breznitz1993). Central to this distinction are ways of coping that bring the individual closer to the stressful situation versus coping that allows the individual to withdraw. Historically, approach responses have tended to be described as positive coping strategies, whereas avoidance has acquired negatively toned descriptions (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Edge and Altman2003). However, we argue that avoidance strategies may be particularly functional for parents as their child declines.

In terms of approach and avoidance coping, there are discussions that these are complementary coping processes, even synergistic, as avoidance may serve a respite function, thus allowing subsequent approach processes (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Edge and Altman2003). This speaks to the concept of balancing coping strategies in order that they can serve an appropriate purpose. This description of coping is particularly useful in the context of imminent loss, which can be emotionally overwhelming and catastrophic. Cognitively and emotionally, it can be too demanding for parents to constantly attend to the catastrophic consequences of what is happening (Rayson, Reference Rayson2013), which speaks to the need for respite and avoidance.

Denial in the palliative phase is a useful concept to illustrate the positive and negative consequences of a given cognitive effort or behavior. In clinical practice, denial is both seen as a psychological coping mechanism and as an obstacle for planning end-of life care (Rayson, Reference Rayson2013). It is described as unconscious and healthy, in temporarily providing the patient with respite from the reality of death. While it has protective and adaptive functions, providing respite and a buffer, its persistent use can become maladaptive and pathological (Zimmermann, Reference Zimmermann2004; Reference Zimmermann2007).

Therefore, the central premise of the framework describing coping strategies for parents is that avoidance (such as denial) and approach coping strategies are used by parents and that a balance between these strategies will result in the best outcomes.

Social Coping (Self and Family, Child, Spouse, Siblings)

Qualitative research of the parents of children with cancer has indicated that support for parents needs to come in the form of enabling mothers and fathers to fulfill their different roles effectively, which means understanding the roles and experiences in more depth. In addition, any support that may undermine this role is unlikely to be effective (Young et al., Reference Young, Dixon-Woods and Findlay2002). Parents of children with a complex illness adopt multiple roles—such as nurse, child advocate, and detective—while trying to be a good parent, to ensure that the child is well and has a good life (Hinds et al., Reference Hinds, Oakes and Hicks2009; Woodgate et al., Reference Woodgate, Edwards and Ripat2015), and caregiving roles play a part in complex decision making (Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Schmitt and Gedney Baggs2012).

In managing their emotions, mothers caring for a child with cancer highlighted the importance of carrying and sharing their child's burden. In addition, they felt that they should shield children from adult emotions, leading to a demand to maintain a cheerful disposition (Young et al., Reference Young, Dixon-Woods and Findlay2002). This illustrates the balance between the parents' own coping and that employed to support the child. The emphasis on the child's needs is also underscored when parents highlight the “obligation of proximity,” that is, the need to be physically close to the child in order to monitor and comfort them. Parents find it difficult to realize that a break from such selflessness may actually help their own coping as well as that of their child, and such a break may require support and encouragement from the healthcare team as well as from others (Young et al., Reference Young, Dixon-Woods and Findlay2002).

For parents and other caregivers, the social aspect of coping, in the context of family systems and dyadic relationships, becomes important, whereby coping strategies can benefit others (such as the child or spouse) instead of the parent. A review on distress in the families at the end of life highlighted evidence about the distress that reverberates throughout the family system (Carolan et al., Reference Carolan, Smith and Forbat2015; Forbat et al., Reference Forbat, McManus and Haraldsdottir2012). Coping as an interpersonal process points to the challenge of using coping strategies aimed at personal emotion-regulation and family system emotion-regulation.

Balancing Coping Strategies

Some past investigations on coping have tended to identify coping strategies that have positive or negative outcomes. There is evidence that, rather than identifying coping strategies that lead to maladjustment, an investigation into the most effective coping strategies can give insight into the importance of balance in self-regulation (Metcalfe & Mischel, Reference Metcalfe and Mischel1999). In addition, expression of positive expectations while facing threats should be seen as a person's effort to find meaning, rather than an indication that a person is not coming to terms with his/her situation (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, Reference Aspinwall and Tedeschi2010).

In order to avoid labeling coping strategies as either positive or negative (Campos et al., Reference Campos, Frankel and Camras2004), the framework presented in this manuscript aims to emphasize that effective coping is achieved by balancing different strategies (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Lau and Chan2014). There is a growing focus in the coping literature on “flexibility,” and here we focus predominantly on the use of a “balanced profile” (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Lau and Chan2014). The framework aims to be integrative, allowing strategies to occur simultaneously and seemingly “negative” strategies (such as denial) to be functional in this context (Campos et al., Reference Campos, Frankel and Camras2004). Negative and positive thoughts and feelings can coexist (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, Reference Aspinwall and Tedeschi2010), and thus parents may embrace seemingly contradictory strategies in their efforts to achieve balance. For instance, a study by Darlington and colleagues (Reference Darlington, Dippel and Ribbers2007) investigated coping strategies as set out by Brandstadter and Renner (Reference Brandstadter and Renner1990). The authors found that the combination of higher levels of coping strategies aimed at maintaining or regaining life as it was before it changed (i.e., “tenacious goal pursuit,” a tendency to try to achieve the same activities as before) together with higher levels of coping strategies aimed at adjusting one's goals in line with changed circumstances (i.e., “flexible goal adjustment,” a tendency to adjust goals in light of changing circumstances) was associated with higher levels of well-being (Darlington et al., Reference Darlington, Dippel and Ribbers2007). This reiterates the significance of adopting or balancing simultaneous coping efforts.

There is also evidence from the bereavement literature specifically related to the dual process model (Stroebe & Schut, Reference Stroebe and Schut1999), which discusses adjustment of bereaved individuals and describes how bereaved individuals oscillate between loss-oriented coping and restoration-oriented coping. Shear (Reference Shear2010) further posited the notion of a partnership of loss and restoration, instead of an oscillating pattern, which is in line with coping strategies occurring in parallel. For instance, there is evidence in the palliative care literature that hope and acceptance can coincide (Kamihara et al., Reference Kamihara, Nyborn and Olcese2015; Mack et al., Reference Mack, Wolfe and Cook2007). Hope has been described as essential for maintaining quality of life, and hope changes over time (from hope for a cure to hope for a painless death, for instance) as the child deteriorates (Granek et al., Reference Granek, Barrera and Shaheed2013). There is a need to maintain hope while being given realistic information both for parents (Granek et al., Reference Granek, Barrera and Shaheed2013; Smith, Reference Smith2014) and the children (Jalmsell et al., Reference Jalmsell, Lovgren and Kreicbergs2016), with family members describing living parallel realities (Smith, Reference Smith2014). This evidence supports the notion of trying to achieve a balance while using different coping strategies in parallel.

In summary, the central assumption of the theoretical framework is that fluidity between and among the poles is normal and healthy for parents of dying children, whereas a fixed state in any given quadrant is likely problematic. We propose the following hypotheses: (1) high levels of use of each of the coping strategies will result in higher levels of well-being for parents, and (2) higher use of a specific coping strategy and lower use of other coping strategies will result in lower levels of well-being for parents.

In order to clarify the framework (Figure 1) in more detail, we will go on to present the different coping strategies in each quadrant, describing the behaviors and thoughts that are illustrative of each quadrant and accompanying them with a patient vignette. Sarah is a 7-year-old girl who was diagnosed with a stage 4 neuroblastoma (malignant tumor of the adrenal gland) two years earlier. She underwent a year of chemotherapy, a bone marrow transplant, surgery, and radiation, and did well. About a year after completing therapy, a routine surveillance scan revealed multiple liver and bone metastases. Sarah's parents were informed by the medical team that there were some treatment options but that they were not curative, and at best they could only prolong her life for a few months. Her parents decided not to give her any further chemotherapy, but to allow her to live as normal a life as possible for as long as possible. Sarah lives with her parents and two older brothers.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF QUADRANTS

Avoidance – Family-Focused Coping (Quadrant 1)

Sarah's parents are numb with shock after hearing the news. Sarah loves school and wants to continue to go to school. Her parents tell her that as long as she is feeling up to it, of course she can go to school, and as long as she gets her homework done, she can play with her friends after school. Her brothers want to know if she can still come watch them at their soccer tournament. Her parents tell them that “Sarah is still Sarah,” and she can continue to live the life she's led since finishing chemotherapy. In fact, they said, they are all going to be a normal family and do the things that normal families do (family dinners, going to school, family vacations, and sporting events), just like they were doing a week ago before they got the news that Sarah's cancer was back.

A combination of avoidance and family-focused coping is illustrated by the parents' attempts and efforts to normalize or maintain normality (Price et al., Reference Price, Jordan and Prior2011). Palliative care research in adults emphasizes the importance of maintaining normalcy (Mosher et al., Reference Mosher, Ott and Hanna2015) and maintaining the lifeworld (Wrubel et al. Reference Wrubel, Acree and Goodman2009). The authors highlighted that there is a perception of people who are faced with eventual death as living admirable lives in the face of adversity, whereas this distorts and diminishes the value of day-to-day living (Wrubel et al., Reference Wrubel, Acree and Goodman2009). Moreover, research has emphasized the importance of family rituals in adaptation (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Crespo and Canavarro2015), which mirrors the notion of normalizing. Family rituals evoke feelings of security (Fiese, Reference Fiese2006), which are essential during a phase riddled with such uncertainty. Sarah's family embraced rituals like family dinners, school, and sports. They seized upon the normal things in their lives, when so much of normalcy had been taken away from them.

There is evidence from parents of a child with cancer undergoing active treatment that keeping positive during the first year after diagnosis as a means of coping can keep family life functioning effectively (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Hill and Ward2012). Moreover, during active treatment, parents have reported the need to help children pass as “normal,” in order to protect the child's identity from becoming synonymous with the illness (Young et al., Reference Young, Dixon-Woods and Findlay2002).

Avoidance – Self-Focused Coping (Quadrant 2)

Sarah has a visit with the oncologist. She is still feeling good and going to school, but she has lost a little weight and has some aches and pains (easily controlled with ibuprofen). Her parents have been researching complementary and alternative therapies. Her parents and the oncologist again discuss prognosis, but at the same time, Sarah's mother talks about her joining the soccer team with her brothers next year and the more rigorous year of school coming during the next academic year. She also talks about a vacation they plan to take in six months. The oncologist thinks, “I thought they got it, but it seems they just don't get it.”

Avoidance of the enormity of what is unfolding, with a focus on the self (and thus a combination of avoidance and self-focused coping for parents), is exemplified by evidence from a qualitative study (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Hill and Ward2012) that reported parents living life, taking life day by day in order to cope with the magnitude of what was happening. This short-term focus was a conscious decision by parents to put their fears aside in order to function effectively (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Hill and Ward2012). Other studies have highlighted the importance of denial, which has been described as a highly adaptive coping mechanism (Rayson, Reference Rayson2013). A qualitative study on caregivers of adult patients stressed the importance of denial (Rose, Reference Rose1997). This is reiterated by evidence from bereaved people who used experiential avoidance to avoid the intense pain, which initially enabled continued functioning (Shear, Reference Shear2010). As highlighted earlier, hope is an important source of coping. While parents can hope for a cure, as time goes on this can change into hope for other things (such as more time; Granek et al., Reference Granek, Barrera and Shaheed2013; van der Geest et al., Reference van der Geest, van den Heuvel-Eibrink and Falkenburg2015). Sarah's parents actually do “get it,” but there is a part of them that needs to talk about Sarah's future, even though at the same time they know what the future actually holds for her, as exemplified by the phrase used by parents—“Hope for the best, prepare for the worst”—reported by Lotz et al. (Reference Lotz, Daxer and Jox2016).

Another significant theme in the context of avoidance is that of maintaining control. The palliative and end-of-life phase can be characterized as lacking in a sense of control and certainty. A study investigating parents' outlook in relation to their child undergoing stem cell transplantation found that parents reported infrequent thoughts about deteriorating health while understanding the risks. The authors proposed that parents focus on immediate challenges instead of the more distant outcomes in order to maintain a level of control (Ullrich et al., Reference Ullrich, Rodday and Bingen2016). In another study, mothers described how they navigated and got involved in care in order to get a sense of control amid the chaos (Price et al., Reference Price, Jordan and Prior2011). Sarah's parents' exploration of alternative therapies is an example of trying to get some control of a situation that is actually spiraling out of control. In addition, parents focus on protecting their child, which includes fighting for them, advocating for them, and protecting their child from infections. This active role allows practical involvement, and thus some control (Price et al., Reference Price, Jordan and Prior2011; Young et al., Reference Young, Dixon-Woods and Findlay2002).

Approach – Self-Focused Coping (Quadrant 3)

Sarah is too sick to go to school. She is taking morphine for her bone pain, and she is sleeping a lot. Her parents take leave from work, and they counsel her brothers that Sarah is dying and that she has little time left in this world. They spend every waking moment with her and often sleep with her. They hold her tight and softly cry as they prepare for a life without her. In some ways, they feel they have already lost the healthy, vibrant Sarah they knew, and, although she has not died, they feel she is already gone.

Anticipatory grief is a central feature of approach-oriented coping focused on the self. Anticipatory grief has been described as a process of mourning in response to anticipated loss (Rando, Reference Rando2000). Parents report feeling worried about the negative things to come, as well as sadness and longing (Al-Gamal, Reference Al-Gamal2013). In addition, knowledge of the child's imminent death aids in preparing for the death, enabling parents to mourn the loss prior to the actual time (Rini & Loriz, Reference Rini and Loriz2007). In some parents, a degree of disengagement from the child has been described, in an attempt to protect against further pain and loss (Contro et al., Reference Contro, Kreicbergs, Riechard and Wolf2011). Parents may engage in anticipatory grief more as the child's physical well-being deteriorates. Parents can find it difficult to contextualize when children are currently physically relatively well (Contro et al., Reference Contro, Kreicbergs, Riechard and Wolf2011). Moreover, attempting to create meaning (Steele, Reference Steele2000) under these circumstances will aid parents in coming to terms with the imminent death. Sense-making has been shown to increase positive outcomes after the child's death (Gillies & Neimeyer, Reference Gillies and Neimeyer2006; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Currier and Neimeyer2010), as illustrated by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Bonanno and Duhamel2008) in a study on parents of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Parents who were searching for meaning presented with worse outcomes after the child's death than those who were able to find meaning, indicating that achieving sense-making is beneficial for some parents (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Bonanno and Duhamel2008).

Approach – Family-Focused Coping (Quadrant 4)

Sarah is having more pain and is missing a few days of school every week because she is tired. Her parents decide that now is the time to take a family vacation to Florida before Sarah gets too weak to travel. When they suggest this to Sarah, she asks them, “Am I dying?” They ask her why she asked such a question. She said, “because everyone is being so nice to me.” She went on to tell them that she has talked to her brothers about dividing up her toys for them. Sarah's parents are shocked that she and her brothers know so much. They cry and tell her they are worried, but that they will always be with her. After this conversation, there is a palpable lessening of tension in the home. They realize it is time to stop the alternative therapies. They have a wonderful trip to Disneyland and spend a lot of time after looking at photographs of their trip. They also look at pictures of when Sarah was a little girl and tell stories of the words Sarah said funny when she was a baby. The parents cherish every moment they can hold her tight.

Approach-oriented coping, combined with a focus on the child and family, reflects the attachment theory paradigm (Kearney & Byrne, Reference Kearney and Byrne2015). Attachment theory outlines that the natural bond between parent and child will drive parents to fulfill a protective function, thus providing a secure base and safe haven for the child. The role that parents take in working to prevent the child's condition from deteriorating—“holding the fort” (Steele, Reference Steele2000), relinquishing goals and pursuing new goals (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Miller and Walter2014), and trying to be “a good parent” (Hinds et al., Reference Hinds, Oakes and Hicks2009)—all illustrate the focus on the family and problem solving in order to achieve the best outcomes for the child and others. Perhaps that is what Sarah's parents were doing when they let go of the alternative therapies and focused on keeping Sarah comfortable and safe. In addition, parents consciously attempt to live in the present and prioritizing goals, especially those related to parenting (Brown & Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2015; Kars et al., Reference Kars, Grypdonck and Beishuizen2010; McGraw et al., Reference McGraw, Truog and Solomon2012). Attachment theory can also explain parents' relentless pursuit of a cure and aggressive treatment (Kearney & Byrne, Reference Kearney and Byrne2015).

Approach-oriented coping focused on the family can also be illustrated by parents actively creating memories (Tan et al., Reference Tan, Docherty and Barfield2012). Families move ahead to do things that they may have initially put off, while the child with the illness can still participate (e.g., a trip to Disneyland or the ocean). Sarah's parents did so with their trip to Florida. In addition, they consolidated older memories as they reviewed Sarah's life story in photographs. There is evidence that engaging in wish fulfillment for the child is a positive experience for the family (Darlington et al., Reference Darlington, Heule and Passchier2013).

Parents work at maintaining roles of family functioning, as well as finding new ways to manage things in order to actively preserve the family unit (Price et al., Reference Price, Jordan and Prior2011). Equally, parents provide physical and emotional care of child and family, which can include learning new skills. Emotional work is a substantial part of approach-oriented coping, including such emotions as guilt, fear, exhaustion, isolation, stress, and anxiety. This focus on engaging with emotions and care demands often occurs at the expense of the parents' own health (Price et al., Reference Price, Jordan and Prior2011).

CONCLUSIONS

We have outlined a theoretical framework that aims to describe the coping strategies that parents use when confronted with the knowledge that their child's health is declining and will likely die. The framework emphasizes the importance of balancing coping strategies, specifically: (1) approach and avoidance, and (2) coping aimed at self and others. We hypothesize that high levels of use of each of the coping strategies will result in higher levels of well-being for parents, whereas higher use of a specific coping strategy and lower use of other coping strategies will result in lower levels of well-being for parents. Future work will see further testing of these hypotheses, as well as providing empirical evidence for our framework. Moreover, data collection (e.g., by adapting currently available questionnaires) will encompass novel ways of analyzing data in order to assess and present a balanced coping profile. Furthermore, future work could focus on longitudinal as well as real-time data collection in order to capture the dynamic quality of coping (Litt et al., Reference Litt, Tennen, Affleck and Folkman2010), which may be especially relevant for this group with constantly changing circumstances. Finally, future work should explore the usefulness of possibly discussing coping profiles with the parents as an intervention. This may be able to support health professionals in fostering prognostic communication, enabling them to implement some of the principles outlined within our theoretical framework. Conversations around advanced care planning can incorporate the exploration of coping strategies (Lotz et al., Reference Lotz, Daxer and Jox2016), which may make a contribution to the delivery of difficult conversations and supporting parents, children and families. Enabling coping strategies in parallel and integrating these principles in practice will allow health professionals to support parents and families more effectively.