Introduction

Peninsular Thailand's latest Cambrian strata comprise interbedded fossiliferous sandstones and rhyolitic ash beds, making this succession particularly important for resolving the geochronology of the Cambro-Ordovician boundary (Stait et al., Reference Stait, Burrett and Wongwanich1984). Previous studies of Thailand's Cambrian trilobites (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988) recovered a mix of taxa both endemic to Thailand and shared with Australia, North China, or South China. Here we show that more taxa remain to be discovered and identified that help further resolve the biostratigraphic succession of Thailand and its paleogeographic association with other Gondwanan terranes. Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp. is one such new taxon. Satunarcus n. gen. belongs to Kaolishaniidae (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935) and, while morphologically distinctive, bears close resemblance to genera known from Australia, North China, and South China.

Trilobites of the corynexochid suborder Leiostegiina, particularly tsinaniids and kaolishaniids, are prevalent in the late Cambrian (Furongian) record from equatorial Gondwana. They occur in Sibumasu, South and North China, Bhutan, and Australia (Sun, Reference Sun1924; Shergold, Reference Shergold1972, Reference Shergold1975, Reference Shergold1991; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2010, 2013; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Myrow, McKenzie, Harper, Bhargava, Tangri, Ghalley and Fanning2011; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014). The evolution and dispersal patterns of Kaolishaniidae Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi1935) and Tsnianiidae Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi1933) reflect Cambro-Ordovician paleogeography during the final accretion of Gondwana prior to its mid-Paleozoic breakup (Cawood et al., Reference Cawood, Johnson and Nemchin2007). These trilobites are also useful index taxa for establishing Stage 10 biozones, including the Shergoldia nomas Zone of Australia and the Ptychaspis-Tsinania and Kaolishania pustulosa Zones of North China (Geyer and Shergold, Reference Geyer and Shergold2000). The discovery of a new kaolishaniid genus, Satunarcus, from Thailand's Tarutao Group and its affinities with various genera traditionally classified as Mansuyiinae Hupé (Reference Hupé1955) prompts a revision of this subfamily and its role in the evolution of Tsinaniidae from Kaolishaniidae.

Tsinaniids have been scrutinized in numerous studies on the origins of higher-level taxa that became prominent during the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event. They have alternatively been suggested as a sister taxon to Asaphida (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2007) or as an early family in, or sister taxon to, the derived corynexochid suborder, Illaenina (Fortey, Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997; Adrain, Reference Adrain2011). The asaphid hypothesis has been strongly refuted (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2009; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2010), while the basal illaenid hypothesis is not well supported, although classification schemes listing Tsinaniidae as an illaenid remain current (Adrain, Reference Adrain2011). As a result of investigations into the potential role of Tsinaniidae as a sister taxon to more derived Ordovician groups, several different cladistics-based phylogenetic schemes have arisen for the emergence of Tsinaniidae, with the general consensus being that the family is rooted in Kaolishaniidae (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013; Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014). In each of these phylogenies, Mansuyia Sun, Reference Sun1924 is important in the split between Tsinaniidae and other kaolishaniids. In one cladistic analysis, Mansuyia resolved as a paraphyletic stem genus to Tsinaniidae (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014), with the holaspid retention of pygidial spines linking it to Kaolishaniidae and the ventral median suture and overall pygidial form excluding the spines linking it to Tsinaniidae. In another analysis, Mansuyia was made the outgroup to tsinaniids, thus providing no meaningful information on the relationship between Kaolishaniidae and Tsinaniidae, while assuming a polarization of characters from Mansuyia to Tsinaniidae (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013). In yet a third study, the relationship among Kaolishania Kobayshi, Reference Kobayashi1935, Mansuyia, and tsinaniids was an unresolved polytomy (Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014).

All three cladistic investigations into the tsinaniid-kaolishaniid link suffer from a lack of focus on the kaolishaniid taxa. Park et al. (Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014) and Lei and Liu (Reference Lei and Liu2014) each used only a single kaolishaniid species apart from Mansuyia in the analysis; in Park et al. (Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014), it is the outgroup, forcing a Mansuyia-Tsinaniidae connection. Additionally, no members of the taxa assumed to be Mansuyia's closest relatives, the Mansuyiinae Hupé, Reference Hupé1955, were included in any analysis. When considering the position of Mansuyia in regards to kaolishaniids and tsinaniids, the placement of taxa generally considered Mansuyia's closest relatives, the other Mansuyiinae, must be considered. Mansuyiinae is vaguely characterized as “Mansuyia-like taxa” (Shergold, Reference Shergold1972). Because Manusyia is the type genus of Mansuyiinae, any questions of its affinity should also consider the affinities of the entire subfamily.

The discovery of a new kaolishaniid trilobite from the Ao Mo Lae Formation of the Tarutao Group of southernmost peninsular Thailand prompts a reevaluation of kaolishaniid and tsinaniid systematics, with emphasis on the inclusion of a broader range of Mansuyiinae genera. The most similar previously published material comes from Australia and was originally assigned to Mansuyia cf. orientalis due to its comparable pygidium (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, Reference Shergold1991), but for both the Thai and Australian material Mansuyia cf. orientalis is an unsatisfactory designation. Specimens from both collections are more similar to Mansuyiinae genera other than Mansuyia itself, particularly in the large, flat preglabellar area. The cladistic analysis described herein was initially conducted to evaluate the generic placement of the Thai and Australian material, but it reveals new insight into kaolishaniid-Mansuyia-tsinaniid evolution by restricting Mansusyiinae as it is currently understood and revealing a previously unrecognized clade within Kaolishaniidae.

Geologic and stratigraphic context

Western Thailand, along with northern Malaysia, eastern Myanmar, and western Yunnan, China, is part of the peri-Gondwanan terrane known as Sibumasu (Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2002) or the Shan-Thai block (Bunopas, Reference Bunopas1982). To date, the island Ko Tarutao (Fig. 1) has the best-studied Cambrian fossils from Sibumasu (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957; Stait et al., Reference Stait, Burrett and Wongwanich1984; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988); they are found in the Tarutao Group (Javanaphet, Reference Javanaphet1969), a clastic unit dominated by sandstone that forms the base of the Paleozoic succession in western Thailand. The Tarutao Group contains a diverse latest Cambrian and earliest Ordovician faunal assemblage, including the newly discovered Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp. Its best exposed and accessible outcrops are on Ko Tarutao itself, Thailand's southern-most island, which is ~25 km off the west coast of Satun province and ~5 km north of Langkawi, Malaysia. There are some outcrops of the Tarutao Group on the mainland, but these are mainly quartzite, having experienced low-grade regional or contact metamorphism (Wongwanich et al., Reference Wongwanich, Tansathien, Leevongcharoen, Paengkaew, Thiamwong, Chaeroenmit and Saengsrichan2002); no fossils have been found outside of Ko Tarutao. The Machinchang Formation of Langkawi is the southern lithologic continuation of the Tarutao Group and does bear some fossils (Lee, Reference Lee1983).

Figure 1. Geologic map of Ko Tarutao, Thailand with localities from which Satunarcus n. gen. was discovered (Modified from Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988).

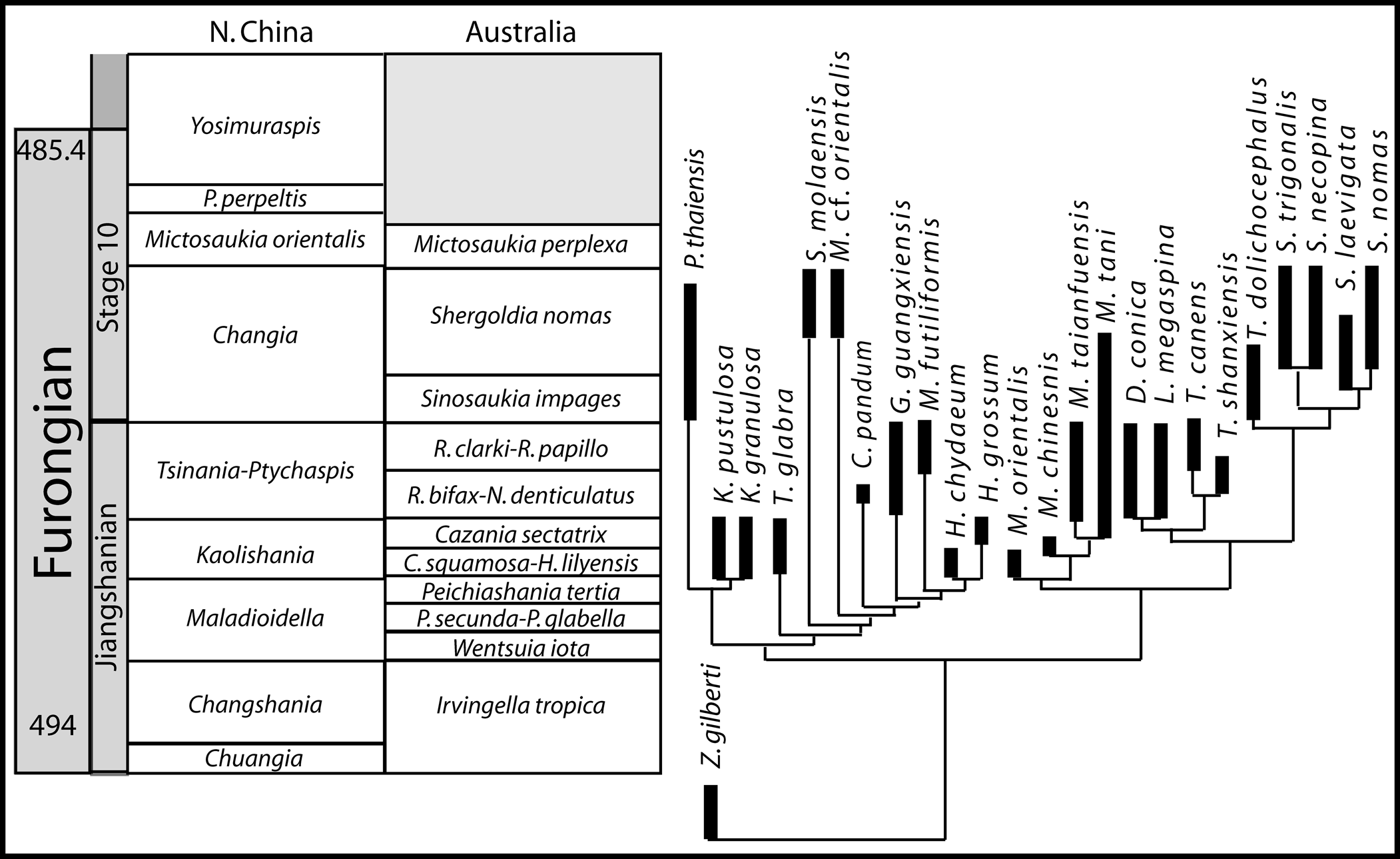

The Tarutao Group extends from the upper Furongian into the Tremadocian, where it transitions into the limestone of the Thung Song Group (Bunopas, Reference Bunopas1982; Stait et al., Reference Stait, Burrett and Wongwanich1984). The exact thickness of the Tarutao Group is difficult to estimate due to faulting; exposures occur only as isolated coastal headland outcrops in short sections separated by long covered intervals. Total thickness estimates range from 800 m (Bunopas et al., Reference Bunopas, Muenlek and Tansuwan1983) to 3,100 m (Teraoka et al., Reference Teraoka, Sawata, Yoshida and Pungrassami1982). Shergold et al. (Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988) accepted a conservative view of 850 m, which we consider more reasonable than estimates surpassing 1,000 m. At present, we have collected Cambrian fossils from four localities: Ao Phante Malaca, Ao Molae, Ao Talo Topo, and Ao Talo Udang. Satunarcus n. gen. has been found only at Ao Molae (06°40′13.68″N, 099°38′1.38″E) and Ao Talo Topo (06°40′8″N, 099°37′6.12″E), where it occurs in association with another genus first described from Ko Tarutao, the dikelocephalid Thailandium Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957. The fossil assemblages at these two localities suggest that they are from near the base of Cambrian Stage 10, and equivalent in age to the Changia trilobite zone of North China (Sun, Reference Sun1924; Zhou and Zhen, Reference Zhou and Zhen2008; Peng, Reference Peng2009) and the Sinosaukia impages through Shergoldia nomas zones of Australia (Fig. 2), ~489 Ma (Shergold, Reference Shergold1972). The outcrops at Ao Talo Toppo and Ao Molae are from the Ao Mo Lae Formation, the stratigraphically lowest fossiliferous part of the Tarutao Group (Imsamut and Yathakam, Reference Imsamut and Yathakam2011).

Figure 2. Trilobite biostratigraphic zones of North China and Australia and stratigraphic constraint of the tsinaniid and kaolishaniid cladogram. The taxa with abbreviated generic names are Pseudokoldinioidia perpeltis, Rhaptagnostus clarki, Rhaptagnostus papillo, Rhaptagnostus bifax, Neagnostus denticulatus, Caznaia squamosa, Hapsidocare lilyensis, Peichiashania secunda, and Prochuangia glabella (Shergold, Reference Shergold1972, Reference Shergold1975, Reference Shergold1991; Geyer and Shergold, Reference Geyer and Shergold2000; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2007; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Hughes, Heim, Sell, Zhu, Myrow and Parcha2009; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2010, Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Myrow, McKenzie, Harper, Bhargava, Tangri, Ghalley and Fanning2011; Park et al., Reference Park, Sohn and Choi2012, Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014; Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014).

All specimens from Ao Talo Topo described herein were collected from a single horizon during our scouting expedition in 2008. Unfortunately a later excursion, during which the section was measured, failed to find Satunarcus n. gen. at Ao Talo Topo, although numerous other species were found. Without the recovery of at least some of the key species that co-occur with Satunarcus n. gen., such as Thailandium and Pagodia, it is not possible to place Satunarcus n. gen. within the section. The first fossils ever published from Ko Tarutao were from a lithologically and biostratigraphically comparable horizon though in a different section (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988). Specimens from Ao Molae (horizons 1 and 2) were also collected at the time of the expedition to Ao Talo Topo, in addition to during a later visit in December 2016. Ao Molae has an ~11 m thick section through the Ao Mo Lae Formation, with fossiliferous beds confined to the middle part (Fig. 3). Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp. itself has been recovered from only the upper half of the fossiliferous beds (4.71–6.01 m) of the Ao Molae section. When Ao Talo Topo and Ao Molae collections are considered together, S. molaensis n. gen. n. sp. co-exists with Eosaukia buravasi Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957, Thailandium solum Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957, Quadraticephalus planulatus (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957), Hoytaspis? thanisi Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988, and Lichengia? tarutaoensis (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957). It is the recovery of Eosaukia, Thailandium, and Quadraticephalus that suggests stratigraphic equivalency with the Sinosaukia impages and Changia zones of Australia and North China, respectively.

Figure 3. Ao Molae measured section and range chart. Section height is measured in meters.

The Tarutao Group is primarily composed of hummocky, cross-bedded and parallel-bedded, fine-grained quartzarenite with a minor component of siltstone and shale, and is interbedded with rhyolitic volcanic ash and breccia (Fig. 3). Fossils are primarily in coquina horizons within the sandstone beds (Fig. 4). Fossiliferous horizons are readily identifiable in cross section in the outcrop as thin (<1 cm), pitted horizons oriented parallel to bedding, from which internal and external molds can be retrieved. All Satunarcus n. gen. were recovered from such horizons, but a small number of other fossils, including trilobites, brachiopods, and cephalopods, are isolated within the sandstone and oriented obliquely to bedding. All fossils within the Tarutao Group are disarticulated, with the degree of fragmentation ranging from absent to unidentifiable scleritic hash. The molds forming the coquina horizons at Ao Talo Topo and Ao Molae are in some cases whitened by secondary silica precipitation that partially infill the mold. Preservation as molds in fine-grained sandstone precludes the occurrence of early ontogenetic stages, and only disarticulated holaspid sclerites have been recovered. For Satunarcus n. gen., pygidial and cranidial associations can be made with reasonable confidence on the basis of size, frequency of occurrence, and inferred taxonomic affinity, but no librigena, hypostomes, or thoracic segments have been found of the right size and morphology to make them a plausible match. This study's cladistic analysis is restricted to characters of mature holaspid cranidia and pygidia because this is the only information available for most tsinaniid and kaolishaniid taxa, including Saturnarcus n. gen.

Figure 4. Photo of Ao Talo Topo bedding; the white arrow points to a pitted, fossiliferous shellbed horizon. Hammer included for scale.

Characters and taxa used in cladistic analysis

The cladistic analysis of Tsinaniidae and Kaolishaniidae presented herein use a heuristic examination of 51 characters, with a total of 91 character states, across 24 ingroup taxa and one outgroup (Table 1). The ingroup taxa were chosen based on the following criteria: (1) taxonomic significance of species—type species such as Mansuyia orientalis Sun, Reference Sun1924 and Tsinania canens (Walcott, Reference Walcott1905) were favored because their characteristics are central to evaluating their generic concepts; (2) use in recent tsinaniid phylogenetic studies (including Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013; Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014)—taxa used in these studies were favored in order to facilitate comparisons between the results of these different phylogenetic analyses; (3) quality of published figures—analysis was based primarily on figured specimens, and those with only low resolution or poor-quality images from older publications are less useful in providing confident character-state assignments; and (4) taxonomic breadth of coverage—we favored sampling a wide range of genera from within Mansuyiinae more than multiple species within a single genus. Exceptions were made for Shergoldia and Tsinania because the monophyly of these genera is particularly questionable.

Table 1. Matrix of character states for each taxon. See the in-text list of characters for the description of each numbered character and its states.

Previous analyses of Kaolishaniidae and Tsinaniidae used Kaolishania granulosa Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1933, Kaolishania pustulosa Sun, Reference Sun1924, or Mansuyia orientalis Sun, Reference Sun1924 as outgroups, all of which belong to either Kaolishaniidae or Tsinaniidae (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013; Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014). However, in order to evaluate the relationship between kaolishaniids and tsinaniids, it is important to use an outgroup that is not a member of either. Because the relationships between kaolishaniids and tsinaniids may have implications for the derivation of Illaeniina from Leiostegiina, we chose to use an outgroup from the third Corynexochida suborder, Corynexochina, which is stratigraphically older than either Illaeniina or Leiostegiina. Zacanthoides gilberti Young and Ludvigsen, Reference Young and Ludvigsen1989 is suitable as the outgroup because it is a well-known, stratigraphically older representative of Corynexochina.

Cladistic analysis used the following species. For measurements we used the noted specimens as they are relatively complete an unambiguous representatives of the species.

-

Zacanthoides gilberti Young and Ludvigsen, Reference Young and Ludvigsen1989.—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Young and Ludvigsen, Reference Young and Ludvigsen1989, pl. 6, figs. 12, 13, 16, pl. 7, fig. 2).

-

Ceronocare pandum Shergold, Reference Shergold1975.—Two cranidia and one pygidium (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 43, figs. 1, 7, 8).

-

Dictyella conica Shergold, Laurie, and Shergold, Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007.—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007, figs. 27.a, 27.c, 27.j, 27.o, 27.r).

-

Guangxiaspis guangxiensis Zhou in Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Liu, Meng and Sun1977.—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2010, fig. 5.9, 5.10).

-

Hapsidocare chydaeum Shergold, Reference Shergold1975.—One cranidium and three pygidia (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 40, fig. 1, pl. 41, figs. 1–3).

-

Hapsidocare grossum Shergold, Reference Shergold1975.—One cranidium and one pygidium (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 42, figs. 1, 5).

-

Kaolishania granulosa Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1933.—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1960, pl. 20, figs. 11, 12; Park et al., Reference Park, Sohn and Choi2012, fig. 8.a, 8.b, 8.y).

-

Kaolishania pustulosa Sun, Reference Sun1924.—Three cranidia and three pygidia (Sun, Reference Sun1924, pl. 3., fig. 8.a, 8.e; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Chang, Chu, Chien and Hisang1965, pl. 81, figs. 1, 4; Qian, Reference Qian1994, pl. 27, figs. 5, 8).

-

Lonchopygella megaspina Zhou in Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Liu, Meng and Sun1977.—Three cranidia and three pygidia (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Liu, Meng and Sun1977, pl. 55, figs. 11, 12; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013, figs. 2.22, 2.23, 3.30, 3.31).

-

Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp.—Nine cranidia and six pygidia (Figs. 9, 10).

-

Mansuyia chinensis (Endo, Reference Endo and Aoki1939).—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014, fig. 3.B, 3.H, 3.L, 3.N).

-

Mansuyia orientalis Sun, Reference Sun1924.—Three cranidia and two pygidia (Qian, Reference Qian1994, pl. 32, figs. 5, 6, 11, pl. 33, figs. 1, 3).

-

Mansuyia cf. orientalis (Sun, Reference Sun1924; sensu Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, Reference Shergold1991).—Four cranidia and two pygidia (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 38, figs. 6, 7; 1991, pl. 2, figs. 2, 4–6).

-

Mansuyia taianfuensis (Endo, Reference Endo and Aoki1939).—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Endo, Reference Endo and Aoki1939, pl. 2, figs. 21, 22; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014, fig. 6.f, 6.h)

-

Mansuyia tani Sun, 1935.—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014, fig. 5.b, 5.g, 5.l, 5.p).

-

Mansuyites futiliformis Shergold, Reference Shergold1972.—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Shergold, Reference Shergold1972, pl. 13, figs. 1, 6, pl. 14, figs. 1, 4)

-

Pagodia thaiensis Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957.—Two cranidia and one pygidium (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957, pl. 4, figs. 5–7).

-

Shergoldia laevigata Zhu, Hughes, and Peng, Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2007.—Three cranidia and two pygidia (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2007, figs. 2.c, 2.f, 3.e).

-

Shergoldia necopina (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975).—Two cranidia and one pygidium (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 48, figs. 2, 3, 5).

-

Shergoldia nomas (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975).—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 47, figs. 1–3, 5).

-

Shergoldia trigonalis (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975).—One cranidium and two pygidia (Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, pl. 50, figs. 3, 7, 8).

-

Taipaikia glabra (Endo in Endo and Resser, Reference Endo and Resser1937).—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Endo and Resser, Reference Endo and Resser1937, pl. 69, fig. 21; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Myrow, McKenzie, Harper, Bhargava, Tangri, Ghalley and Fanning2011, figs. 9.e, 9.g, 10.c).

-

Tsinania canens (Walcott, Reference Walcott1905).—Three cranidia and two pygidia (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014, fig. 7.a–7.c, 7.g, 7.j).

-

Tsinania dolichocephala (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1933).—Three cranidia and two pygidia (Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014, figs. 6.a–6.c, 6.g, 6.h).

-

Tsinania shanxiensis (Zhang and Wang, Reference Zhang and Wang1985).—Two cranidia and two pygidia (Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014, figs. 3.d, 3.f, 5.m, 5.o).

Fifty-one characters of holaspid cranidia and pygidia were considered and possess a mix of binary and multi-state attributes. All quantitative character states are based on discrete breaks in character distributions. Characters that could not be coded for a species because of missing data or inapplicable features were coded as missing, indicated by “?.” Characters inapplicable to the outgroup do not have an assigned state zero, and are also indicated by “?” (as in Carlucci et al., Reference Carlucci, Westrop and Amati2010 and Wernette and Westrop, Reference Wernette and Westrop2016). The characters and character states are given below.

1. Anterior border dorso-ventral convexity.—(0) Convex, (1) Concave, (2) Flat.

2. Anterior border furrow lateral condition (the appearance of the lateral part of the anterior border furrow).—(0) Distinct, (1) Faint, (2) Effaced.

3. Anterior border furrow medial condition (the appearance of the medial part of the anterior border furrow).—(0) Distinct, (1) Faint, (2) Effaced.

4. Anterior margin shape.—(0) Evenly curved, (1) Triangular.

5. Anterior margin angularity (the angularity of the triangular-shaped anterior margin from character 4[1]).—(1) Roundish, (2) Blunt, (3) Sharp, (4) Concave.

6. Anterior border lateral corner position.—(0) Opposite preglabellar furrow, (1) Anterior to glabella.

7. Preglabellar field.—(0) Absent, (1) Present.

8. Preocular facial suture orientation.—(0) Divergent, (1) Convergent.

9. Extent of preocular facial suture deflection (only applicable for taxa with character 8[0]).—(0) >33°, (1) <33°.

10. Facial suture and anterior margin intersection.—(0) Lateral, (1) Axial (facial suture anterior branches fuse on dorsal surface).

11. Maximum anterior area width (tr.) divided by preoccipital glabellar length (sag.).—(0) <110%, (1) 110–129%, (2) 130–149%, (3) ≥150%.

12. Widest (tr.) point on preocular cranidium.—(0) On anterior border, (1) Posterior to anterior border.

13. Plectrum.—(0) Absent, (1) Present.

14. Preglabellar furrow expression.—(0) Incised, (1) Inflected (preglabellar border defined by a sharp change of slope), (2) Faint.

15. Axial furrow expression.—(0) Deep, (1) Shallow, (2) Effaced.

16. Lateral glabellar furrow expression.—(0) Distinct, (1) Faint, (2) Effaced.

17. Preglabellar and anterior border furrow confluence.—(0) Confluent, (1) Separate.

18. Preglabellar and axial furrow junction.—(0) Defined, (1) Continuous curve.

19. Axial furrow bacculae.—(0) Absent, (1) Present.

20. Median glabellar ridge.—(0) Present, (1) Absent.

21. Posterior glabellar narrowing (posterior end of L1 distinctly narrower [tr.] than anterior).—(0) Absent, (1) Present.

22. SO medial anterior bend.—(0) Present, (1) Absent.

23. LO width relative to L1.—(0) Same, (1) LO narrower, (2) LO wider.

24. LO termination at axial furrows.—(0) Pinched (LO shortens [exsag.] as it approaches the axial furrows), (1) Blunt (LO truncates against axial furrows).

25. Transverse postoccipital ridge (a flange or ridge on the posterior edge of the occipital ring).—(0) Absent, (1) Present (Fig. 5.1).

26. Anterior fixigenal termination (the feature against which fixigena terminate anteriorly).—(1) Anterior border (fixigena terminate against the anterior border furrow), (2) Preglabellar field (the preglabellar field separates the fixigena from the anterior border).

27. Adaxial position of fixigenal termination (the position of the adaxial end of the line denoting the anterior edge of the fixigena).—(1) Opposite glabella, (2) Anterior to glabella (Fig. 5.2).

28. Glabellar adaxial fixigenal termination (for taxa with character 27[1] the glabellar feature against which the anterior adaxial fixigenal corner terminates).—(1) Anterior glabellar corner, (2) Preglabellar border (Fig. 5.2).

29. Palpebral lobe curvature (how strongly curved the adaxial edge of the palpebral lobe is).—(0) Strong, (1) Weak.

30. Palpebral lobe curvature evenness.—(0) More curved posteriorly, (1) Evenly curved.

31. Exsagittal position of palpebral lobe anterior point.—(0) Anterior to S2, (1) Opposite S2, (2) Opposite L2.

32. Palpebral lobe posterior position.—(0) Posterior to S1, (1) Opposite S1.

33. Eye ridge.—(1) Absent, (2) Present.

34. Eye ridge condition (only applies to taxa with character 33[2]).—(1) Faint, (2) Distinct.

35. Postocular facial suture shape.—(1) Increasingly arched toward posterior, (2) Straight, (3) Increasingly arched abaxially (Fig. 5.3).

36. Cranidial posterior border shape.—(0) Nearly straight, (1) Distinctly curved.

37. Posterior border furrow length (exsag.).—(1) Consistent length, (2) Abaxially lengthening.

38. Anterior pygidial corner shape (the extent of rounding at the inflection where the anterior pygidial border joins the lateral pygidial border).—(0) Rounded, (1) Angular.

39. Anterior pygidial margin shape.—(0) Straight, (1) Arched posterolaterally.

40. Anteriormost pygidial segment length (exsag.).—(0) Distally expanding, (1) Constant.

41. Paired segment-related spines.—(0) Present, (1) Absent.

42. Paired pygidial border spines (pygidial spines extended from undifferentiated border rather than as extensions of segments).—(0) Absent, (1) Present.

43. Posterior pygidial margin shape.—(0) Strongly curved, (1) Gently curved, (2) Triangular.

44. Pygidial axial furrow shape.—(0) Straight, (1) Curved.

45. Macropleural pygidial segment.—(0) Absent, (1) Present.

46. Pygidial border width (sag. and exsag.).—(0) Broad, (1) Narrow, (2) Absent.

47. Pleural bands.—(0) Continue to margin, (1) Fade out gradually before border, (2) Abrupt termination defining border.

48. Pygidial border convexity.—(0) Concave, (1) Convex.

49. Posterior axial termination point.—(0) Pygidial margin, (1) Before pygidial margin.

50. Axial ring shape.—(0) Medial posterior inflection, (1) Straight, (2) Medial anterior inflection.

51. Number of pygidial rings.—(0) Four, (1) Five to Seven, (2) Eight to Nine, (3) 10 or more.

Figure 5. Explanatory illustrations of select characters: (1) post-occipital ridge 25[1]; (2) anterior termination position of inflated fixigenal areas: solid line 27[2], short dash 28[2], long dash 28[1]; (3) post ocular facial suture shape: long dash 35[1], solid line 35[2], short dash 35[3].

Results of Cladistic Analysis

We utilized Mesquite (Maddison, Reference Maddison2001) to build the matrix, Tree Analysis Using New Technology (TNT; Goloboff et al., Reference Goloboff, Farris and Nixon2008) to run the analysis, and Winclada (Nixon, Reference Nixon2002) to map characters and evaluate some support metrics. The heuristic analysis of the matrix of 25 taxa by 51 characters described above used Wagner trees with 100 random seeds and 1000 replications, saving up to 10 trees per replication. The analysis resulted in a single most-parsimonious tree with length 187, CI 37, and RI 67 (Fig. 6). The general structure of the cladogram is two sided and generally follows the currently recognized systematics; kaolishaniids, including Satunarcus n. gen., are on one side and tsinaniids on the other. Exceptions to the traditional classification scheme are that Mansuyia Sun, Reference Sun1924, generally accepted to be a kaolishaniid (Shergold, Reference Shergold1972), shows affinity with the tsinaniids, and Taipaikia Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1960, generally accepted to be a tsinaniid (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1960; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Myrow, McKenzie, Harper, Bhargava, Tangri, Ghalley and Fanning2011), groups with the kaolishaniids. The unambiguous character supporting the grouping of Mansuyia with Tsinaniidae is 11[1] (a preglabellar width that is 110–129% of the glabellar length) (Fig. 7). Character 17[1] (the presence of axial and preglabellar furrows that are smoothly continuous and undifferentiated), with the support of four additional ambiguous characters, supports Mansuyia as its own clade rooting at the base of Tsinaniidae with a Bremer index of four (Fig. 6.1). Tsinania is revealed to be a polyphyletic concept, its members forming a clade only with the inclusion of Shergoldia, Dictyella, and Lonchopygella. No unambiguous characters support the monophyly of Shergoldia, but its basal node has a Bremer support of three. Dictyella and Lonchopygella also fall within the clade encompassing Tsinania and Shergoldia. The node joining Dictyella and Lonchopygella is unambiguously supported by 5[3] (a distinctly angular convexly triangular anterior margin) and 43[2] (a sharply triangular pygidium).

Figure 6. (1) Bremer support for the most parsimonious tree, tree length 187; (2) Bootstrap results from 10000 replicates; numbers are given as percentages. To avoid confusion for genera starting with the same letter, the following scheme is applied: M = Mansuyia; Mt = Mansuyites; S = Shergoldia; St = Satunarcus n. gen.; Tp = Taipaikia; T = Tsinania.

Figure 7. Character optimization for the most parsimonious tree. Numbers on top show the character number and numbers on bottom show the state for that character. Filled circles indicate those characters that are unambiguous. To avoid confusion for genera starting with the same letter, the following scheme is applied: M = Mansuyia; Mt = Mansuyites; S = Shergoldia; St = Satunarcus n. gen.; Tp = Taipaikia; T = Tsinania.

Taipaikia's grouping within Kaolishaniidae, as opposed to Tsinaniidae, is as part of the clade containing Satunarcus n. gen. and the genera formerly assigned to Mansuyiinae, excluding Mansuyia. This clade is supported by three unambiguous characters and a Bremer support index of five. The supporting unambiguous characters include a medially effaced anterior border furrow (3[2]), an anterior border entirely anterior to the glabella, as opposed to the anterior border's lateral corners extending back to opposite or posterior the anterior glabellar margin (6[1]), and an occipital lobe that truncates bluntly at the axial furrows rather than laterally pinching out (24[1]). Within this clade, an even tighter, similarly supported clade exists that includes Satunarcus n. gen., Mansuyites, Ceronocare, Guangxiaspis, Hapsidocare, and Mansuyia cf. orientalis. This clade is unambiguously supported by the fixigena anteriorly terminating against the broad preglabellar field as opposed to the anterior borders, 26[2]. The node joining the group has a Bremer support index of five.

Materials and methods

The specimens were prepared manually using a Dremel tool, blackened with India ink, whitened with ammonium chloride, and photographed with a Leica stereoscopic camera model MZ16. Apart from Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp. itself, the systematic analysis was based exclusively on figures from prior publications. The criteria used in the selection of species for analysis and which specimens were used for measurements are listed in the “Characters and taxa used in cladistic analysis” section above. All figures and plates were created using Adobe Photoshop CC2017 and Adobe Illustrator CS2.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

All Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp. illustrated in this paper are reposited in Thailand's Department of Mineral Resources’ Geological Referenced Sample Collection (DGSC); unfigured specimens are reposited in either DGSC or the Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC).

Systematic paleontology

The systematic paleontology section is authored by Wernette and Hughes.

Class Trilobita Walch, Reference Walch1771

Order Corynexochida Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Suborder Leiostegiina Bradley, Reference Bradley1925

Superfamily Leiostegioidea Bradley, Reference Bradley1925

Family Kaolishaniidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Subfamily Ceronocarinae new subfamily

Type genus

Ceronocare Shergold, Reference Shergold1975.

Type species

Ceroncare pandum Shergold, Reference Shergold1975.

Diagnosis

Ceronocarinae n. subfam. cranidium is distinguished by a long (sag.) frontal area comprising a depressed or flat elongated (sag.) preglabellar field with comparatively short (sag.) anterior border; a broad (tr.) frontal area that reaches maximum width on the anterior border; anterior border with lateral corners anterior to the preglabellar margin; prepalpebrally divergent anterior facial sutures that converge anteriorly to meet medially or are nearly convergent at the anterior cranidial margin; inflated palpebral areas that anteriorly terminate with a moderately strong to sharp inflection point opposite the preglabellar furrow and are separated from the anterior border by a wide (tr. & exsag.) preglabellar field; occipital ring that does not laterally narrow or pinch out at the axial furrows. Pygidia possess one pair of segmentally derived spines and an inflated posterior band on the anterior pygidial segment.

Remarks

Ceronocarinae n. subfam. encompasses genera previously contained in Mansuyiinae, with the exception of Mansuyia Sun, Reference Sun1924. Shergold (Reference Shergold1972) restricted Mansuyiinae to include only “Mansuyia-like” genera. However, the cladistic analysis herein reveals that these “Mansuyia-like” genera are not closely related to Mansuyia, rendering this conception of the subfamily polyphyletic and obsolete. Ceronocare Shergold, Reference Shergold1975, Mansuyites Shergold, Reference Shergold1972, Guangxiaspis Zhou in Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Liu, Meng and Sun1977, and Hapsidocare Shergold, Reference Shergold1975 are no longer assigned to Mansuyiinae, and are hereby reassigned to Ceronocarinae n. subfam., which includes Satunarcus n. gen. This subfamily encompasses those taxa that have a particularly long preglabellar field and inflated palpebral areas anteriorly defined by a sharp inflection point (Fig. 6). Ceronocare displays the most exaggerated form of these characters. It is evident that the preglabellar field is lengthened here, not the anterior border, because an anterior border is visible in some genera, including Satunarcus n. gen., Ceronocare, and Hapsidocare. Homologous depressions in the preglabellar area occur in Tsinania and Mansuyia as a merger between the anterior border and preglabellar furrows, but the condition is much more exaggerated in Ceronocarinae. Ceronocarinae n. subfam. are most diverse in Australia, but also present in South China and Sibumasu. Ceronocare was chosen as the type genus because it best exemplifies the strongly inflated palpebral areas terminating sharply into a long, broad preglabellar field with a very short anterior border whose furrow is medially effaced.

Genus Satunarcus new genus

Type species

Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp.; by original designation; by monotypy.

Diagnosis

As for the type species by monotypy.

Occurrence

Ao Mo Lae Formation of the Tarutao Group of Ko Tarutao, Thailand. Furongian, Cambrian Stage 10, stratigraphically near the boundary between the Sinosaukia impages and Shergoldia nomas trilobite zones of Australia. Ao Talo Topo horizon 1 and Ao Molae horizons 4.71 m, 5.81 m, 5.84 m, and 6.01 m.

Etymology

“Satun-” is in honor of Satun UNESCO Global Geopark where the type species is found; “-arcus” is in recognition of the particularly arched posterolateral projections, an unusual feature useful in distinguishing this genus.

Remarks

Satunarcus n. gen. is a member of Ceronocarinae n. subfam. that may have split from the rest of the subfamily early in its development (Fig. 2). Its general dimensions in terms of preglabellar area and glabellar width and length are similar to Mansuyia cf. orientalis, particularly to specimens from Australia's Pacoota Sandstone, which are preserved under similar lithologic and taxonomic conditions (Shergold, Reference Shergold1991). Nevertheless, M. cf. orientalis is excluded from Satunarcus on account of its long, strongly curved palpebral lobes and narrow, weakly curving posterolateral projections.

Satunarcus molaensis new species

Figures 8–10

Figure 8. Line drawing of Satunarcus molaensis n. gen., n. sp. Gray region on pygidium represents the concave posterior border. Dotted line on preglabellar field is the often-effaced anterior border furrow.

Holotype

DGSC F0343, Figures 9.1–9.3; Ao Mo Lae Formation of the Tarutao Group; Furongian, Cambrian Stage 10; Ao Molae bed 5.81 m. Paratypes: DGSC F0358, F0351, F0356, F0337, Figures 9.8–9.11, 10.3, 10.5, 10.6.

Figure 9. Satunarcus molaensis n. gen., n. sp., all cranidia. (1–3) Holotype: dorsal, anterior, and right lateral views, respectively, DGSC F0343, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m; (4) DGSC F0371, Ao Talo Topo; (5) DGSC F0383, Ao Talo Topo; (6) DGSC F0333, Ao Molae horizon 4.71 m; (7) DGSC F0363, Ao Molae horizon 5.84 m; (8) DGSC F0358, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m; (9) DGSC F0351, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m; (10) DGSC F0356, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m; (11) DGSC F0337, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m. Scale bars are 5 mm.

Figure 10. Satunarcus molaensis n. gen., n. sp., all pygidia. (1) DGSC F0381, Ao Talo Topo; (2) DGSC F0382, Ao Talo Topo; (3) DGSC F0341, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m; (4) DGSC F0384, Ao Talo Topo; (5) DGSC F0360, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m; (6) DGSC F0359, Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m. Arrows point to spine bases. Scale bars are 2.5 mm.

Diagnosis

Cranidium with long, broad, flat or slightly concave frontal area dominated by preglabellar field with indistinguishable or poorly differentiated anterior border; hourglass-shaped glabella relatively narrow (tr.) and short (sag.); palpebral lobes short (exsag.), weakly curved; palpebral areas anteriorly terminate at broad preglabellar field; posterolateral projections broad and strongly posteriorly arched. Pygidium with broad, semielliptical outline; five axial rings; axis terminating bluntly at posterior border; posterior border narrows medially.

Occurrence

Ko Tarutao, Thailand at localities Ao Talo Topo, undetermined horizon, and Ao Molae horizons 4.71 m, 5.81 m, 5.84 m, and 6.01 m; Ao Mo Lae Formation, Tarutao Group; Furongian, Cambrian Stage 10.

Description

Glabellar width at L1 35–40% cranidial width across palpebral areas; total glabellar length 55–60% of total cranidial length; anterior margin strongly curved; anterior border poorly differentiated to effaced; preglabellar area long (sag. and exsag.) and flat to slightly concave; preglabellar area maximum width 270–300% L1 glabellar width; anterior suture branches diverge ~15–20°; glabella hourglass shape with rounded anterior margin; preglabellar furrow laterally deep and medially shallowing to effaced; glabella narrowest across L2; three pairs of short (tr.), firmly incised lateral glabellar furrows angled obliquely toward posterior; S1 broadens (exsag.) abaxially; axial furrows weakly incised; S3 very short, nearly effaced; SO deep, but slightly shallowing medially; LO short (sag.) and constant length (sag. and exsag.) across width (tr.); LO forms continuous band with posterior cranidial border, but differentiated from rest of border by distinct axial furrows; LO width (tr.) slightly less than L1 width; palpebral areas moderately inflated, terminating anteriorly at preglabellar field with moderately sharp inflection; palpebral lobes narrow (tr.), straight, and short (exsag.), ~30–35% glabellar length; palpebral lobes angled 10–15° from sagittal axis, anteriorly palpebral lobe connected to S3 by short (exsag.) eye ridge; posterolateral projection broad (tr.) and long (exsag.), forming a curving triangular shape; posterolateral projection curves ~90° of arc, approaching resupinate condition; posterior border curves evenly parallel to posterior margin with broad (exsag.), firmly incised posterior border furrow.

Pygidial width (tr.) ~175% of length (sag.); anterior margin gently curved and medially straight (tr.); posterior margin smoothly and strongly curved but for posterolateral spines; axial length 75–85% of pygidial length, terminating at evenly sloped posterior border; anterior axial width ~25% of maximum pygidial width; axial furrows straight, at 10–15° angle to sagittal axis; five axial segments, excluding terminal piece; axial ring furrows weakly incised and medially arched anteriorly; pleural furrows straight and nearly effaced; posterior band of anterior segment gently expanded; other pleural bands subequal; furrows become obsolete abruptly defining pygidial border; pygidial border narrow (tr., sag.), 15–20% of anterior pygidial width; border narrows sagittally, almost pinching out; one pair of lateral spines apparently related to the posterior band of the first pygidial segment; spine short and thin (tr., exsag., and dorsoventrally) and rarely preserved.

Etymology

Named for the holotype locality Ao Molae and for the Ao Mo Lae Formation, the only geologic unit currently known with this species.

Materials

Cranidia: From Ao Molae horizon 4.71 m, one figured (DGSC F0333); from Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m, five figured and two unfigured (DGSC F0337, F0343, F0351, F0352, F0356, F0358; CMC IP83136); from Ao Molae horizon 5.84 m, one figured (DGSC F0363); from Ao Molae horizon 6.01 m, two unfigured (CMC IP83154, IP83160); from Ao Molae horizon 2, one unfigured (CMC IP83165); from Ao Talo Topo, two figured and three unfigured (DGSC F0371, F0372, F0383, F0385, F0386). Pygidia: from Ao Molae horizon 5.81 m, three figured and 11 unfigured (DGSC F0341, F0344; F0353, F0359, F0360, F0361; CMC IP83129, IP83130, IP83135, IP83137–IP83139, IP83141, IP83142); from Ao Molae horizon 5.84 m, three unfigured (CMC IP83143–83145); from Ao Molae horizon 6.01 m, two unfigured (CMC IP83153, IP83161); from Ao Talo Topo, three figured and three unfigured (DGSC F0373, F0374, F0381, F0382, F0384, F0387). All specimens are internal molds preserved in fine-grained sandstone, except IP83136, which is an external mold in sandstone.

Remarks

Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp.is a small species with cranidia rarely exceeding 5 mm in length. While ornamentation is easily distinguishable on both the cranidium and pygidium of Mansuyia cf. orientalis in its distinctive palpebral and posterolateral regions, in S. molaensis n. gen. n. sp. it is unknown due to their small size, sandstone preservation, and scarcity of external molds. The spines on the pygidium are exceptionally poorly preserved; they are typically preserved only as outward extensions of the impression left from the border in an otherwise smoothly rounded pygidial margin. Confidence that this is a spine rather than irregularity in the matrix comes from the marginal disruption consistently occurring in the same position on multiple specimens. Satunarcus molaensis n. gen. n. sp. is found at two separate but geographically close localities with similar lithofacies. At Ao Molae, where the stratigraphy is better known and fossils more broadly sampled, S. molaensis n. gen. n. sp. is stratigraphically restricted to a range of <1 m, which may explain why it has not been recovered in previous analyses of the Tarutao fauna (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Burrett, Akerman and Stait1988). Where it does occur, S. molaensis n. gen. n. sp. is moderately abundant.

Discussion

This is the first phylogenetic analysis of tsinaniids and kaolishaniids to include a variety of taxa from both groups. Previous studies, which were constrained in taxon diversity due to the inclusion of ontogenetic data, have used kaolishaniids only as an outgroup for evaluating the tsinaniids (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013) or included only a single supposed kaolishaniid genus, Mansuyia, to consider the relationship with tsinaniids (Lei and Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2014; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Lee and Choi2014). The results herein indicate that if Mansuyia were excluded from Kaolishaniidae and reclassified as a tsinaniid, then Kaolishaniidae forms its own clade separate from Tsinaniidae. If Mansuyia is a member of Kaolishaniidae, then this family is paraphyletic with Tsinaniidae emerging out of it. Because the nature of evolution inherently results in paraphyletic groupings, there is no reason to reassign Mansuyia based on these results. Mansuyia itself is a well-supported clade, contrary to Park et al.'s (2014) view of Mansuyia as a stem group to the Tsinaniidae. The other genera previously assigned to Mansuyiinae, excluding Mansuyia, form their own well-supported clade, herein designated Ceronocarinae n. subfam., within the Kaolishaniidae. Because a polyphyletic taxon is incompatible with evolution-based taxonomy, Mansuyiinae is henceforth restricted to the genus Mansuyia. The Ceronocarinae n. subfam. are characterized by a long (sag.) and broad (tr.) frontal area consisting of an extended and nearly flat preglabellar field and short anterior border, prepalpebrally divergent anterior sutures that converge anteriorly to meet medially, inflated palpebral areas that terminate with a moderately strong to sharp inflection point opposite the preglabellar furrow, and a pygidium possessing one pair of segmentally derived spines and an inflated posterior band on the anterior pygidial segment.

Taipaikia has historically been included with Tsinaniidae, which are generally characterized as large, effaced trilobites (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1960; Jell and Adrain, Reference Jell and Adrain2002). However, this classification has previously been challenged by Taipaikia's abaxial intersection between the facial suture sand the anterior margin (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2007; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Myrow, McKenzie, Harper, Bhargava, Tangri, Ghalley and Fanning2011). Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013) presented a cladistic scheme that supports the classification of Taipaikia as a tsinaniid more closely related to Tsinania and Shergoldia than to Mansuyia, but that analysis did not test the relationship of Taipaikia to tsinaniids, because it assumed, a priori, Mansuyia as the outgroup. This forced the tree to be rooted on Mansuyia with Taipaikia ingroup to Tsinaniidae. The more comprehensive view of Kaolishaniidae provided herein resolves Taipaikia as part of Ceronocarinae n. subfam., and as a kaolishaniid rather than as a tsinaniid (Figs. 6, 7).

Based on the phylogenetic analysis presented here, it is clear that Mansuyia cf. orientalis sensu Shergold (Reference Shergold1975) is not a member of Mansuyia, and is not closely comparable to Mansuyia orientalis. As part of Ceronocarinae n. subfam., its generic affiliation should be reevaluated following a comprehensive revision of the available material.

Conclusions

Satunarcus molaensis is a new species and genus from Ko Tarutao, Thailand. It belongs within the new subfamily Ceronocarinae, erected herein, which contains many of the genera previously assigned to Mansuyiinae. Cladistic analysis of Mansuyiinae, “Mansuyia-like” genera, and related members of Kaolishaniidae and Tsinaniidae reveals that Mansuyia and other genera assigned to Mansuyiinae (Shergold, Reference Shergold1972) are polyphyletic, hence the restriction of the subfamily Mansuyiinae to Mansuyia alone. The subfamily Ceronocarinae n. subfam. is erected to contain the genera formerly considered Mansuyiinae, excluding Mansuyia itself.

Resolution of Tsinania and Shergoldia, the more derived tsinaniids, agrees with Park et al.'s (2014) and Zhu et al.'s (2013) conclusion that, as presently conceived, these genera are not monophyletic. In the previous two studies, Tsinania is nested within Shergoldia, and in this analysis the opposite is true. Given the lower stratigraphic position of Tsinania, the latter analysis is a more stratigraphically consistent branching relationship (Fig. 2). While no non-reversible characters support the monophyly of Shergoldia, reversible supporting characters include the presence of bacculae, an anteriorly directed medial bend in the occipital furrow, and a curved anterior pygidial margin. This analysis additionally agrees with Park et al.'s (2014) view that Lonchopygella is part of the Tsinania-Shergoldia clade, not a sister taxon as depicted in Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Hughes and Peng2013). Lonchopygella is most closely related to Dictyella based on the overall effaced and triangular pygidial and cranidial morphology.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Colorado College undergraduate student, T. White, for digitizing the stratigraphic sections. T. Wongwanich, X. Zhu, S. Peng, and several additional staff from Thailand's Department of Mineral Resources helped to collect specimens on one or both of the Tarutao expeditions. We thank B. Lieberman as associate editor handling our paper and L. Amati and T.-Y. Park for their most helpful reviews. This study was funded by student grants from the Geological Society of America, the American Museum of Natural History (Lerner-Gray Memorial Fund), the Evolving Earth Foundation, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (David Worthington Named Grant), and the Paleontological Society (Allison R. “Pete” Palmer Grant) and by the National Science Foundation grant EAR-1849963 to Hughes and EAR-1849968 to Myrow. Additional funding included NSF grants EAR-053868 and EAR-1124303 that supported contributions from Hughes and EAR-1124518 that supported contributions from Myrow. Hughes acknowledges receipt of Fulbright Academic and Professional Excellence Award 2019 APE-R/107 and thanks the Geological Studies Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata for kindly hosting him. This research is a contribution towards IGCP 668: Equatorial Gondwanan History and Early Palaeozoic Evolutionary Dynamics.