Introduction

Maternal antenatal anxiety and related disorders are very common [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1,Reference Leach, Poyser and Fairweather-Schmidt2], and despite it being frequently comorbid with [Reference Austin, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Priest, Reilly, Wilhelm and Saint3,Reference Falah-Hassani, Shiri and Dennis4], and possibly more common than, depression [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1,Reference Fairbrother, Janssen, Antony, Tucker and Young5], it has received less attention than it deserves in scientific research and clinical practice. Moreover, parental prenatal complications can interfere with the parent–child relationship, with the risk of significant consequences over the years for the child’s development [Reference Milgrom, Schembri, Ericksen, Ross and Gemmill6,Reference Meneghetti7]. From a clinical point of view, this is a considerable omission given the growing evidence that antenatal maternal anxiety can cause adverse short-term and long-term effects on both mothers and fetal/infant outcomes [8–16], including an increased risk for suicide and for neonatal morbidity, which are associated with significant economic healthcare costs [Reference Bauer, Knapp and Parsonage17]. The prevalence of anxiety during pregnancy is high worldwide (up to approximately 37%); however, in low- and middle-income countries, it is higher than in high-income countries [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1,Reference Leach, Poyser and Fairweather-Schmidt2], with heterogeneity across nations with comparable economic status.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between demographic and socioeconomic risk factors with antenatal anxiety [Reference Leach, Poyser and Fairweather-Schmidt2,Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante18]. The results showed that several demographic (e.g., maternal age) and socioeconomic factors (e.g., employment, financial status) were associated with differences in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms or disorders, but the results are equivocal. However, both the prevalence and the distribution of these protective and risk factors may change over time, especially in a period of major socioeconomic change [Reference Dijkstra-Kersten, Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, Van der Wouden, Penninx and Van Marwijk19,Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Bermúdez-Tamayo and Rodríguez-Barranco20], such as the global economic crisis beginning in 2008, which led to the increased consumption of anxiolytic drugs and antidepressants with anxiolytic properties [Reference Vittadini, Beghi, Mezzanzanica, Ronzoni and Cornaggia21], to a decline in the number of births [22] and to impaired development in medical, scientific, and health innovations [Reference Lee and Mason23] that, in the next few years, could reduce the availability of help for families and health services [Reference Reynaud and Miccoli24]. However, despite the recently available and growing research evidence highlighting the need for early identification [Reference Imbasciati and Cena25] and prompt treatment of maternal anxiety during both pregnancy and the postpartum period, anxiety remains largely undetected and untreated in perinatal women in Italy.

The aims of this study were (a) to assess the prevalence of state anxiety in the antenatal period (further stratified by trimesters) in a large sample of women attending healthcare centers in Italy and (b) to analyze its association with demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Methods

Outline of the study

The study was conducted as part of the “Screening e intervento precoce nelle sindromi d’ansia e di depressione perinatale. Prevenzione e promozione salute mentale della madre-bambino-padre” (Screening and early intervention for perinatal anxiety and depressive disorders: Prevention and promotion of mothers’, children’s, and fathers’ mental health) project [Reference Cena, Palumbo, Mirabella, Gigantesco, Stefana and Trainini26] coordinated by the University of Brescia’s Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology and the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS). The main objectives of this Italian multicenter project were to apply a perinatal depression and anxiety screening procedure that could be developed in different structures, as it requires the collaboration and connection between structurally and functionally existing resources, and to evaluate the effectiveness of the psychological intervention of Milgrom and colleagues [Reference Milgrom, Martin and Negri27–Reference Milgrom, Gemmill, Ericksen, Burrows, Buist and Reece29] for both antenatal and postnatal depression and/or anxiety in Italian setting. The research project was assessed and approved by the ethics committee of the Healthcare Centre of Bologna (registration number 77808, dated 6/27/2017).

Study design and sample

We performed a prospective study involving nine healthcare centers (facilities associated with the Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology, University of Brescia, Italy) located throughout Italy during the period, March 2017 to June 2018. The Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology (https://www.unibs.it/node/12195) coordinated and managed the implementation of the study in each healthcare center. Only cross-sectional measures were included in the current analyses because screening for anxiety was carried out at baseline. The inclusion criteria were as follows: being ≥18 years old; being pregnant or having a biological baby aged ≤52 weeks; and being able to speak and read Italian. The exclusion criteria for baseline assessment were as follows: having psychotic symptoms, and/or having issues with drug or substance abuse.

Data collection

Each woman was interviewed in a private setting by a female licensed psychologist. All psychologists were trained in the postgraduate course of perinatal clinical psychology (University of Brescia, Italy) and were associated with the healthcare center. All the psychologists also completed a propaedeutic training course for the study, developed by the National Institutes of Health, on screening and assessment instruments and on psychological intervention [Reference Palumbo, Mirabella, Cascavilla, Del Re, Romano and Gigantesco30]. The clinical interview was adopted to elicit information regarding maternal experience with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression. All women completed the interview and completed self-report questionnaires.

Instruments

Psychosocial and Clinical Assessment Form

The Psychosocial and Clinical Assessment Form [Reference Mirabella, Michielin, Piacentini, Veltro, Barbano and Cattaneo31,Reference Palumbo, Mirabella and Gigantesco32] was used to obtain information on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. In this study, the following demographic variables were considered: age, marital status, number of previous pregnancies, number of abortions, number of previous children (living), planning of the current pregnancy, and use of assisted reproductive technology. The socioeconomic variables were educational level, working status, and economic status.

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory

Given that the assessment of mental diseases, including antenatal diseases, is based primarily on self-perceived symptoms, evaluating these data using valid, reliable, and feasible self-rating scales can be useful. The state scale of the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory [Reference Spielberger, Gorusch and Lushene33–Reference Spielberger35] was used to evaluate anxiety. It is a self-report questionnaire composed of 20 items that measure state anxiety, that is, anxiety in the current situation or time period. The possible responses to each item are on a 4-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. This instrument is the most widely used tool in research on anxiety in women in the antenatal period [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1,Reference Brunton, Dryer, Saliba and Kohlhoff36]. The construct and content validity of the STAI for pregnant women has been proven [Reference Grant, McMahon and Austin37,Reference Gunning, Denison, Stockley, Ho, Sandhu and Reynolds38].

Procedures

Women who met the inclusion criteria were approached by one of the professionals affiliated with the healthcare center and involved in the research when they attended a routine antenatal appointment. They received information about the content and implications of the study. Future mothers who signed the informed consent document completed the questionnaires and then underwent an interview with a clinical psychologist.

Statistical analysis

All variables were categorized. A statistical analysis that included descriptive and multiple logistic regression models was performed. For descriptive analyses, frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, and the Chi-square test was utilized for comparisons. The logistic regression model was used to evaluate the associations between the demographic and socioeconomic variables and the risk of antenatal anxiety. In the analytic models, each demographic and socioeconomic variable was included both individually and together. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25.

Results

Subjects

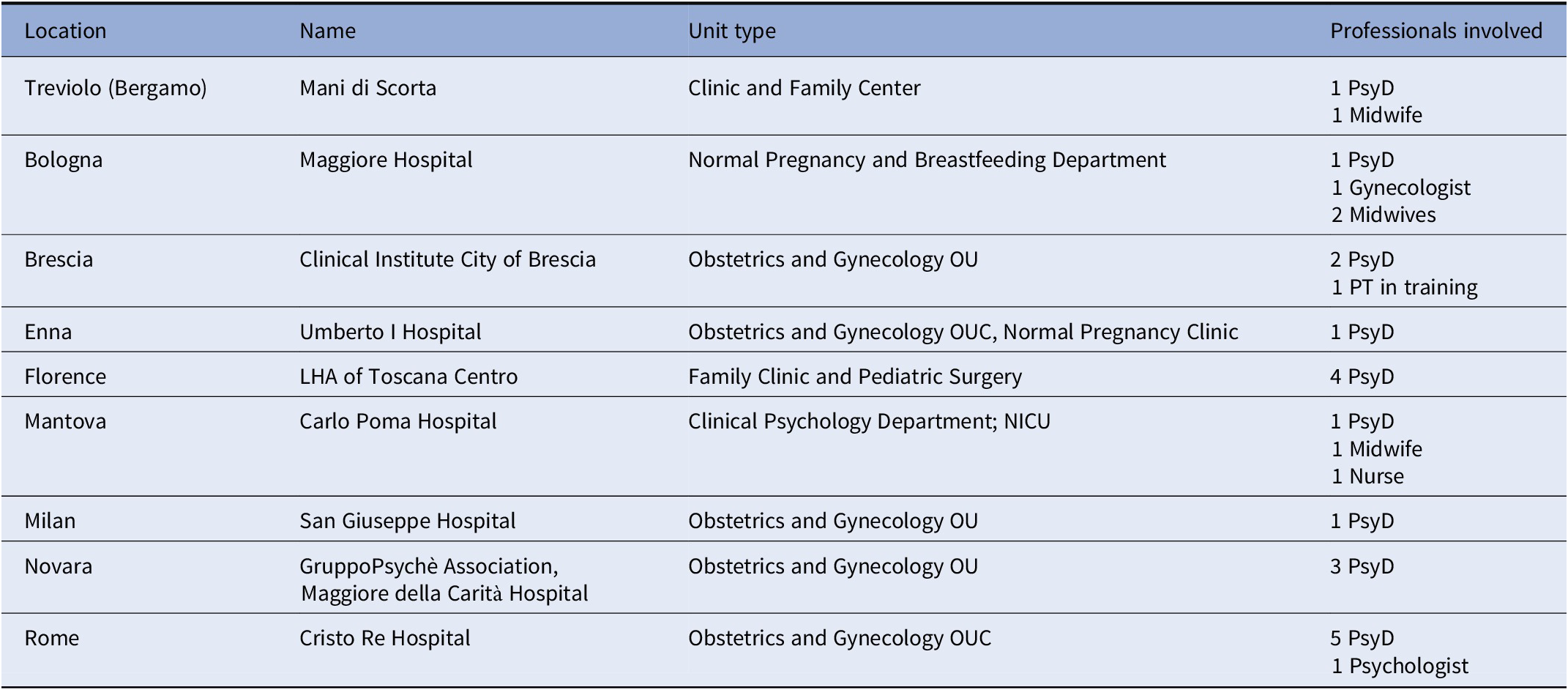

To estimate the minimum sample size, we relied on three studies [Reference Giakoumaki, Vasilaki, Lili, Skouroliakou and Liosis39–Reference Paul, Downs, Schaefer, Beiler and Weisman41], indicating that it was necessary to enroll 296 patients. However, our main aim was to recruit as large a sample as possible to promote perinatal mental health; thus, at the end of the 1-year recruitment period, we enrolled more mothers. Among the 2096 women invited to join the study, 619 (29.5%) refused, mainly due to lack of time, personal disinterest in the topic, and the conviction that they are not and never will become anxious or depressed. Therefore, the total study sample consisted of 1,477 women. Of these, 28 women did not complete the anxiety questionnaire. Thus, the sample includes 1,142 pregnant women and 307 new mothers. Given the aims of this study, only pregnant women were included in the current statistical analysis. Table 1 presents the list of the healthcare centers in which the pregnant women were recruited. Table 2 presents demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, along with an estimation of the relative risk of anxiety through both bivariate and multivariate analyses.

Table 1. Healthcare centers involved in the study (facilities associated with the Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology, University of Brescia, Italy).

Abbreviations: CN, Child Neuropsychiatrist; LHA, Local Health Authority; NICU, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; OU, Unit/Department; OUC, Operating Unit Complex; PsyD, Psychologist–Psychotherapist; RHS, Regional Health Service.

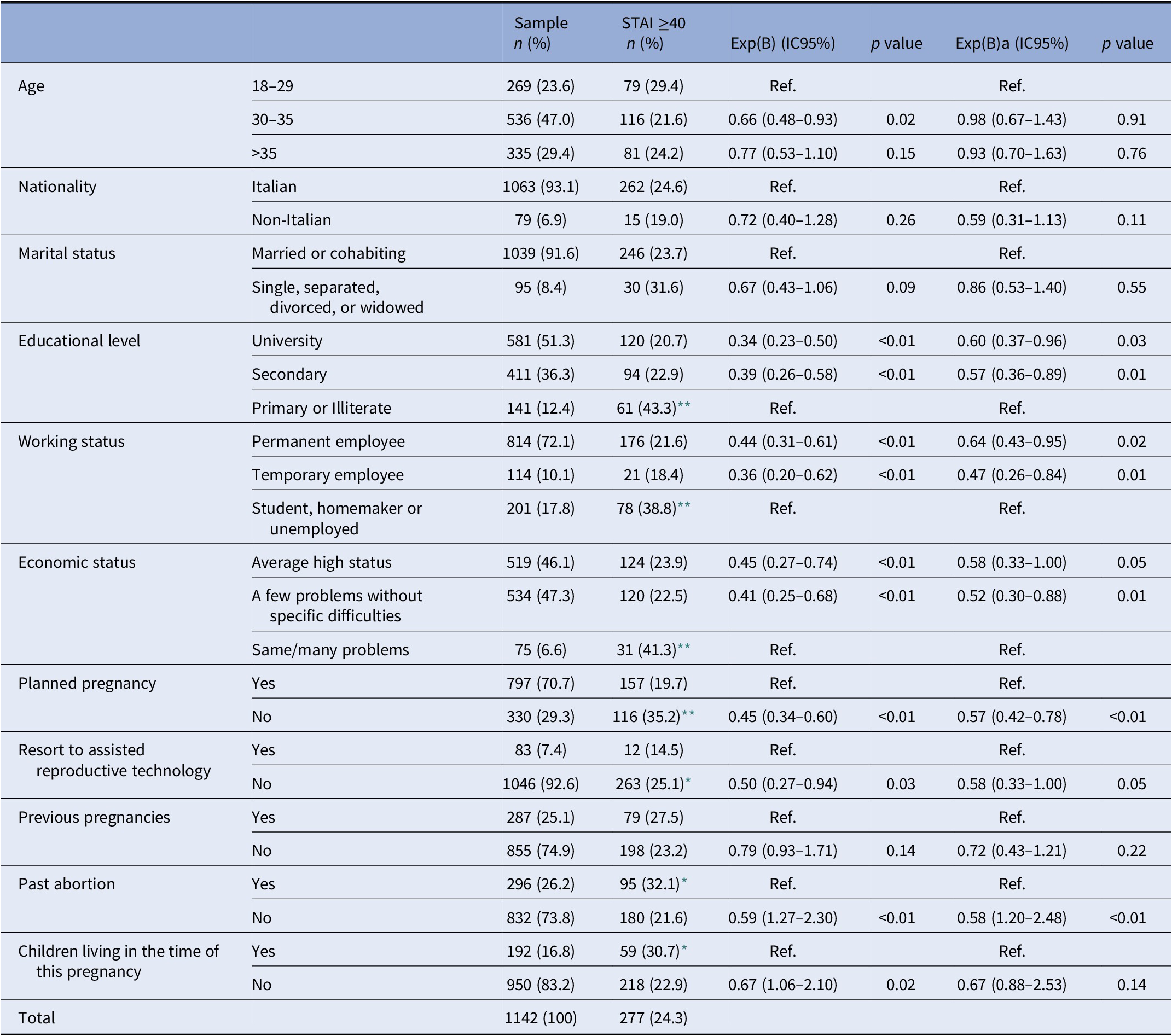

Table 2. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the sample, prevalence of anxiety risk (STAI), and multiple logistic regression model.

Numbers may not sum to total due to missing data.

Exp(B) = exponentiation of the B coefficient; Exp(B)a = exponentiation of the B coefficient adjusted by all demographic and socioeconomic characteristics variables.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

Prevalence of antenatal state anxiety

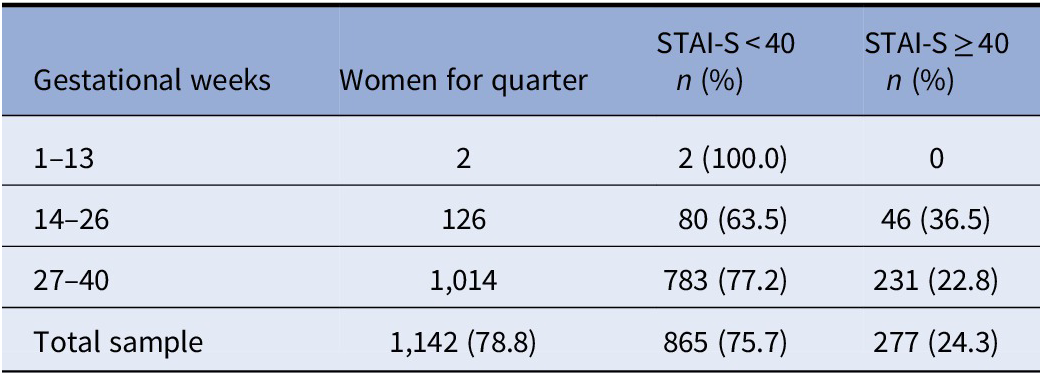

The prevalence of anxiety (Table 3) was 24.3% among pregnant women. A further division into 13-week trimesters was applied, showing that the prevalence of antenatal anxiety was high (36.5%) in the second trimester and then decreased in the third and last trimesters of pregnancy.

Table 3. Results of screening for antenatal anxiety risk separated by trimesters and total frequencies and percentages.

Bivariate analyses (Table 2) showed a significantly higher risk of anxiety in pregnant women who have a low level of education (primary or semiliterate) (p< 0.01), who are jobless (i.e., student, homemaker, or unemployed) (p< 0.01), and who have economic problems (p< 0.01). Furthermore, during the antenatal period, women experienced a higher level of anxiety when they had not planned the pregnancy (p< 0.01), did not resort to assisted reproductive technology (p< 0.05), had a history of abortion (p< 0.05), and had children living at the time of the current pregnancy (p< 0.05).

The adjusted logistic regression analysis (see Table 2) showed that pregnant women with a high (university or secondary) educational level (Exp B = 0.60), temporary or permanent employment (Exp B = 0.64), and, in particular, either a high economic status or few economic problems (Exp B = 0.58) showed a reduction in the risk of antenatal anxiety by almost half. Furthermore, a similar reduction in risk was observed in women who had planned for their pregnancy (Exp B = 0.57).

Discussion

This study is one of the largest to evaluate the prevalence of anxiety during pregnancy in a sample of women attending healthcare centers in Italy. In general, the fact that the demographic data of participants in this study are comparable to those from population-based epidemiological studies [42] indicates that our results are representative of the overall population of pregnant women in Italy. Our findings are in line with the prevalence in a previous Italian study [Reference Giardinelli, Innocenti, Benni, Stefanini, Lino and Lunardi43] and the overall pooled prevalence for self-reported anxiety symptoms of 22.9% reported in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1]. Similarities in the prevalence of maternal antenatal anxiety remain regardless of which diagnostic tool was used. Regarding the use of the STAI in this study, it should be noted that it is the most widely used self-reporting measure of anxiety. Furthermore, its criterion, discriminant and predictive validity [Reference Meades and Ayers44], and ease of use can provide a reasonably accurate estimate of prevalence, and its widespread use in research studies [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1,Reference Grigoriadis, Graves, Peer, Mamisashvili, Tomlinson and Vigod16] can enable more accurate comparisons among nations.

With regard to the trimestral prevalence of antenatal anxiety, our study found that the prevalence of anxiety was highest during the second trimester. This observation is inconsistent with the results from a recent meta-analysis [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1] that found that the prevalence rate for anxiety symptoms increased progressively from the first to the third trimester as the pregnancy progressed. However, it should be noted that the results regarding the monthly/trimestral/semestral prevalence of perinatal anxiety were not univocal in all studies [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1,Reference Leach, Poyser and Fairweather-Schmidt2].

Our study shows that having a low level of education, being jobless, and having financial difficulties are three crucial predisposing factors of anxiety in pregnant women. These associations are clearly consistent with previous studies that found that antenatal anxiety was more prevalent in women with low education and/or low socioeconomic status (e.g., unemployment, financial adversity) [Reference Faisal-Cury and Menezes45–Reference Verbeek, Bockting, Beijers, Meijer, Pampus and Burger49] and might be related to the global economic crisis that currently affects, especially, southern nations [Reference Reibling, Beckfield, Huijts, Schmidt-Catran, Thomson and Wendt50]. Studies conducted in developing countries, where low education and low socioeconomic status are both present, highlight the association with prenatal anxiety [Reference Waqas, Raza, Lodhi, Muhammad, Jamal and Rehman51–Reference Wall, Premji and Letourneau53].

Furthermore, consistent with previous studies, our results show that antenatal anxiety is more prevalent in women who have unplanned pregnancies [Reference Giardinelli, Innocenti, Benni, Stefanini, Lino and Lunardi43,Reference Fadzil, Balakrishnan, Razali, Sidi, Malapan and Japaraj54] and who have living children at the time of the current pregnancy [Reference Zambaldi, Cantilino, Montenegro, Paes, de Albuquerque and Sougey55]. We assume that the reasons for these associations most likely concern the costs associated with raising one or more children, especially when the (new) child is unplanned. This interpretation finds support in the results from previous studies, showing that low income, unemployment, and financial adversity [Reference Leach, Poyser and Fairweather-Schmidt2] are related to higher levels of antenatal anxiety symptoms. Moreover, it would also explain why resorting to assisted reproductive techniques, which in Italy requires financial resources, was not a risk factor.

Our findings regarding the association between ongoing economic hardships or difficulties and antenatal anxiety can be particularly important in light of the short- and long-term adverse impacts of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and restrictive measures adopted to counteract its spread [Reference Stefana, Youngstrom, Hopwood and Dakanalis56,Reference Stefana, Youngstrom, Jun, Hinshaw, Maxwell and Michalak57]. Indeed, the COVID-19 outbreak has significantly impacted European and global economies both in the short term and in the coming years [Reference Fernandes58,Reference McKibbin and Fernando59]. Furthermore, as shown by general population surveys, social isolation related to the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with a wide range of adverse psychological effects, including clinical anxiety and depression and concern about financial difficulties [Reference Pancani, Marinucci, Aureli and Riva60,61], which can persist for months or years afterward, as indicated by the literature on quarantine [Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely and Greenberg62]. A vulnerable population, such as women in the perinatal period, may be among the individuals who are most affected.

Clinical Impact

Our findings suggest that screening for early detection of antenatal anxiety (as well as depression, which is frequently comorbid with anxiety [Reference Austin, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Priest, Reilly, Wilhelm and Saint3,Reference Falah-Hassani, Shiri and Dennis4]) is recommended for all pregnant women, but especially for those who have a poor level of education and financial difficulties. Early detection and diagnosis will enable psychological and, where appropriate, pharmacological treatment in the health services to prevent anxiety complications in both these women and their children.

Limitations

Three main limitations of this study should be noted. First, a cross-sectional approach to antenatal anxiety does not allow us to fully explore whether and what factors may predict persistent anxiety symptoms beginning during pregnancy and progressing to postpartum. Second, the size of the sample during the first trimester of pregnancy was too small to draw any conclusions. Finally, the rates of diagnosis of any anxiety disorder in our sample were not assessed.

Conclusions

There is a significant association between maternal antenatal anxiety and economic conditions. The aftermath of the great recession of 2008–2009 and the ongoing economic impact of the COVID-19 pose a serious problem for women and their families. With the present historical and economic background in mind, our findings would allow us to hypothesize that early evaluation of the socioeconomic status of pregnant women and their families to identify disadvantaged situations might reduce the prevalence of antenatal anxiety and its direct and indirect costs. In this sense, our findings may give Italian health policy planners useful information to develop new cost-effective antenatal prevention programs focused on socioeconomically disadvantaged families. Furthermore, we believe that our results will serve as a baseline for future comparisons between nations inside and outside the European Union, as well as for new studies on the protective and risk factors related to perinatal anxiety in those nations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the women who took part in the study and the professionals in the Italian Healthcare Centers (facilities associated with the Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology, University of Brescia, Italy), for their help in collecting data.

Financial support

This work was self-funded by the Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology - Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences of the University of Brescia (Italy).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Authorship contributions

L.C. and G.P. contributed equally to the general study design. L.C. and A.T. from the Observatory of Perinatal Clinical Psychology coordinate and manage the implementation of the study in each healthcare unit. F.M. and A.S. designed the plan of statistical analysis of the study. A.G. serves primarily as research statistical analysis supervisor. A.S., L.C., and F.M. participated in the writing of the manuscript. G.P. revised the manuscript. All authors have critically reviewed and agreed this final version of the article.

Data availability statement

The complete dataset is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.