Heavy-duty tools have been found on high river terraces in the south of Europe over the past decades (Bourdier Reference Bourdier1958; Collina-Girard Reference Collina-Girard1975; Tavoso Reference Tavoso1978). Recently, beryllium-10 isotope and electron spin resonance dates yielded ages from one million years ago for terraces of the Eastern Pyrenees, highlighting the interest of such archaeological findings for dating and characterising the earliest occupation phases of Europe (Delmas et al. Reference Delmas, Calvet, Gunnell, Voinchet, Manel, Braucher, Tissoux, Bahain, Perrenoud and Saos2018).

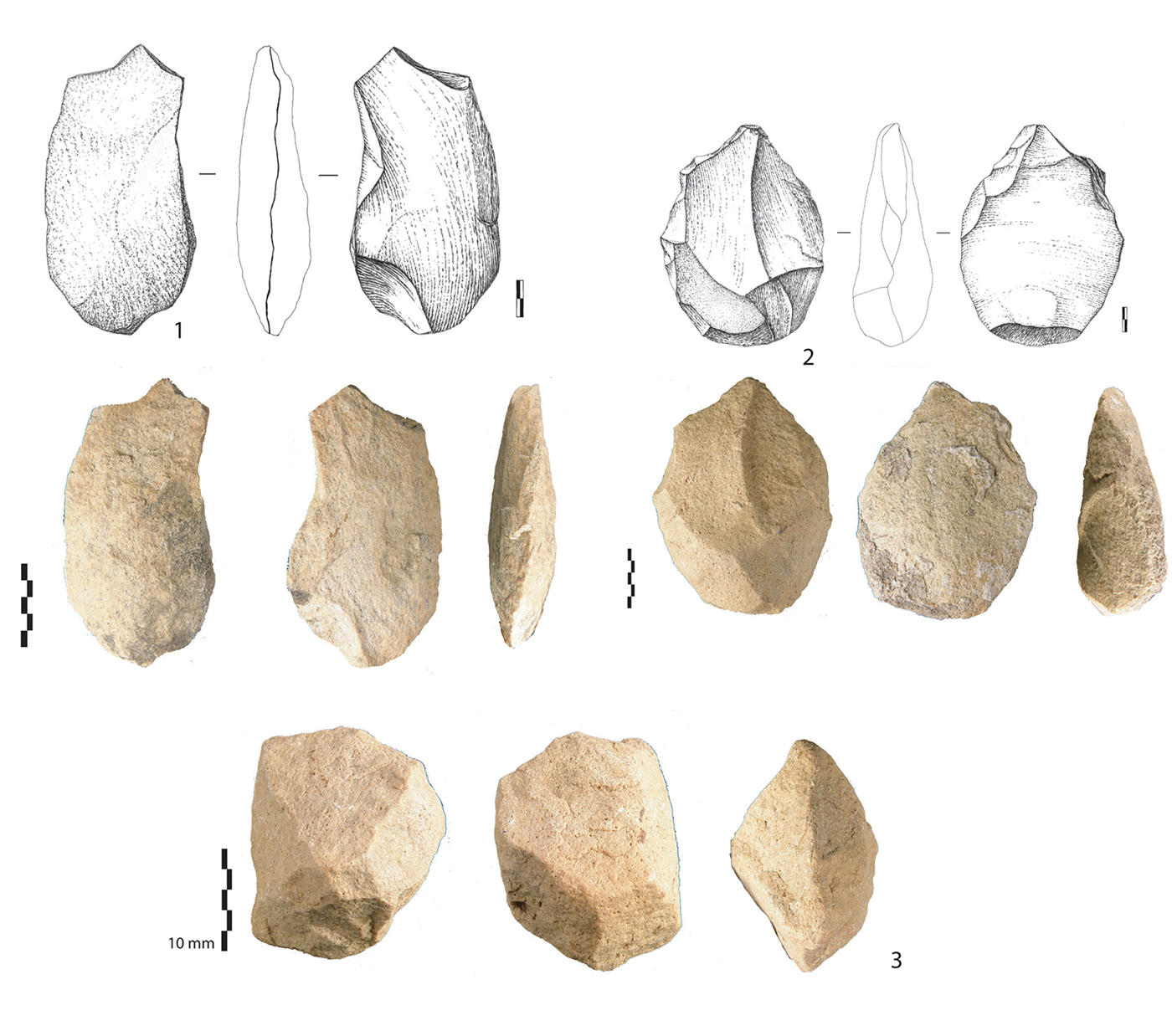

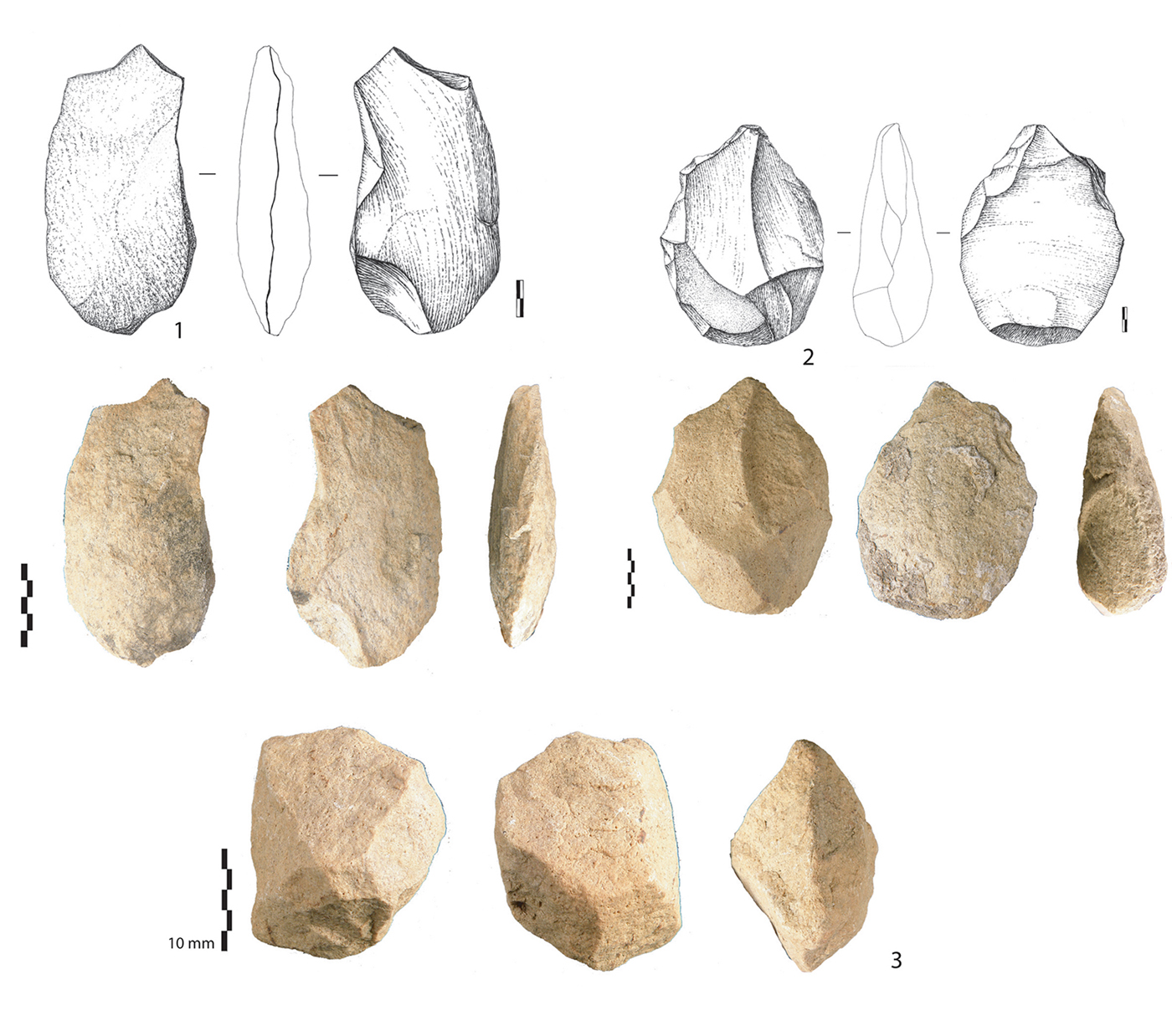

The study area is located on the east flank of a limestone plateau above the middle part of the Rhône Valley, close to the terminal part of the Ardèche Gorges. The elevation is between 160 and 175m asl (Figures 1–3). Seven large flakes (0.15–0.20m long) and one core in quartzite were found in the alluvial deposits (Figure 4). Scars are centripetal or unipolar. The thick platforms are cortical or flat. The core is bi-pyramidal with percussion impacts.

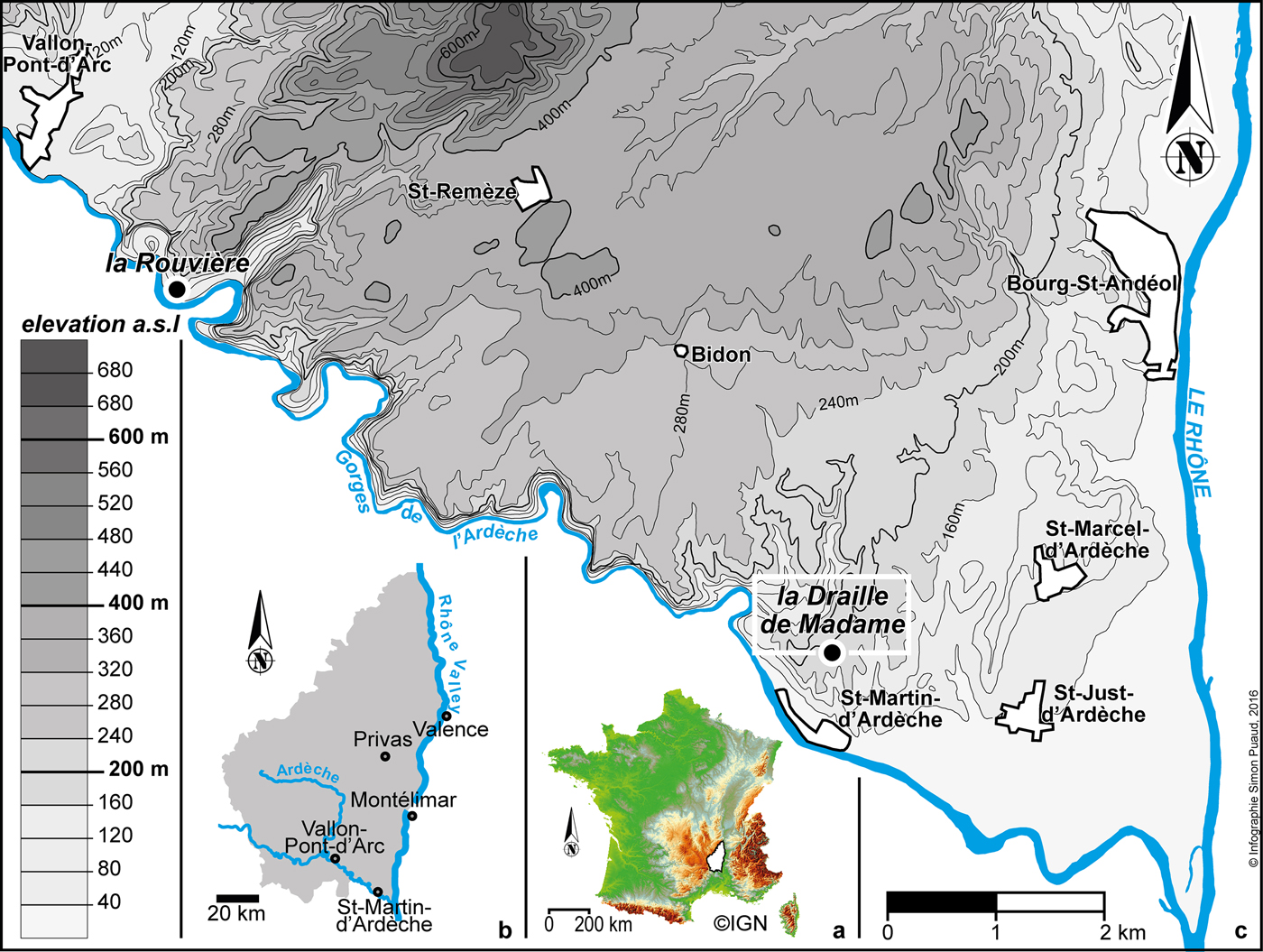

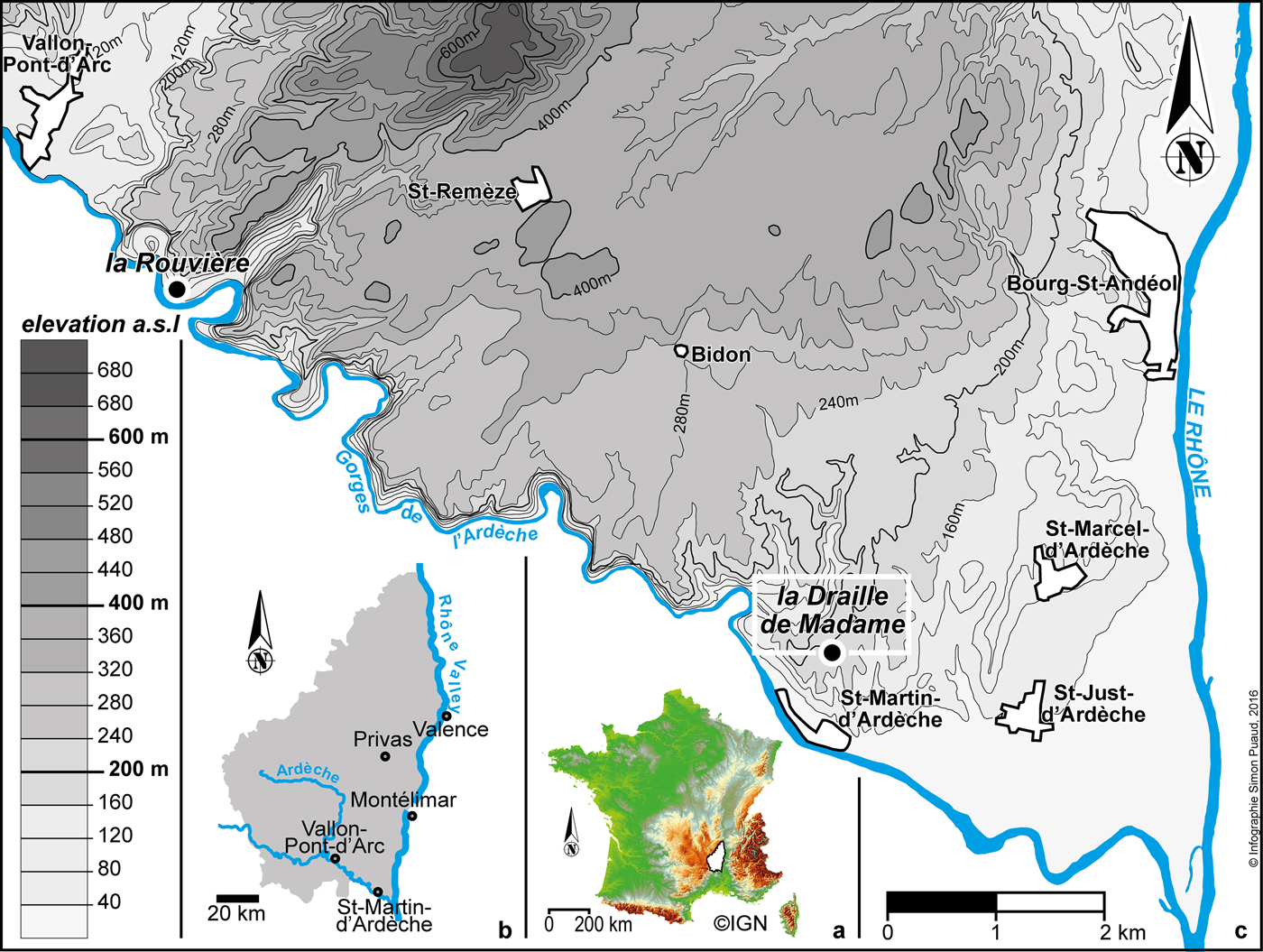

Figure 1. Map of the middle part of the Rhône Valley, showing the right (north) bank of the river; the site is located on the interfluve at 160–175m asl (figure by Simon Puaud).

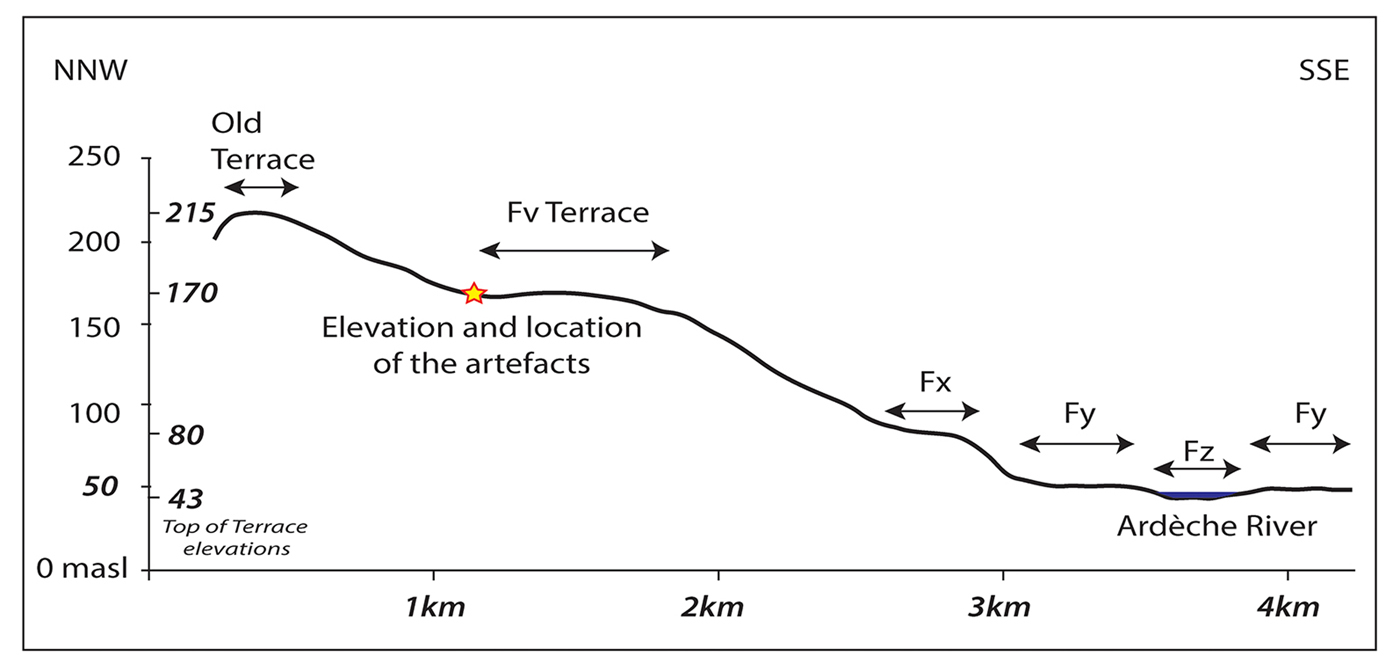

Figure 2. Detailed location of the Fv alluvial terrace; the star marks the location of artefacts (modified after Pascal et al. Reference Pascal, Elmi, Busnardo, Lafarge, Truc and Valleron1989).

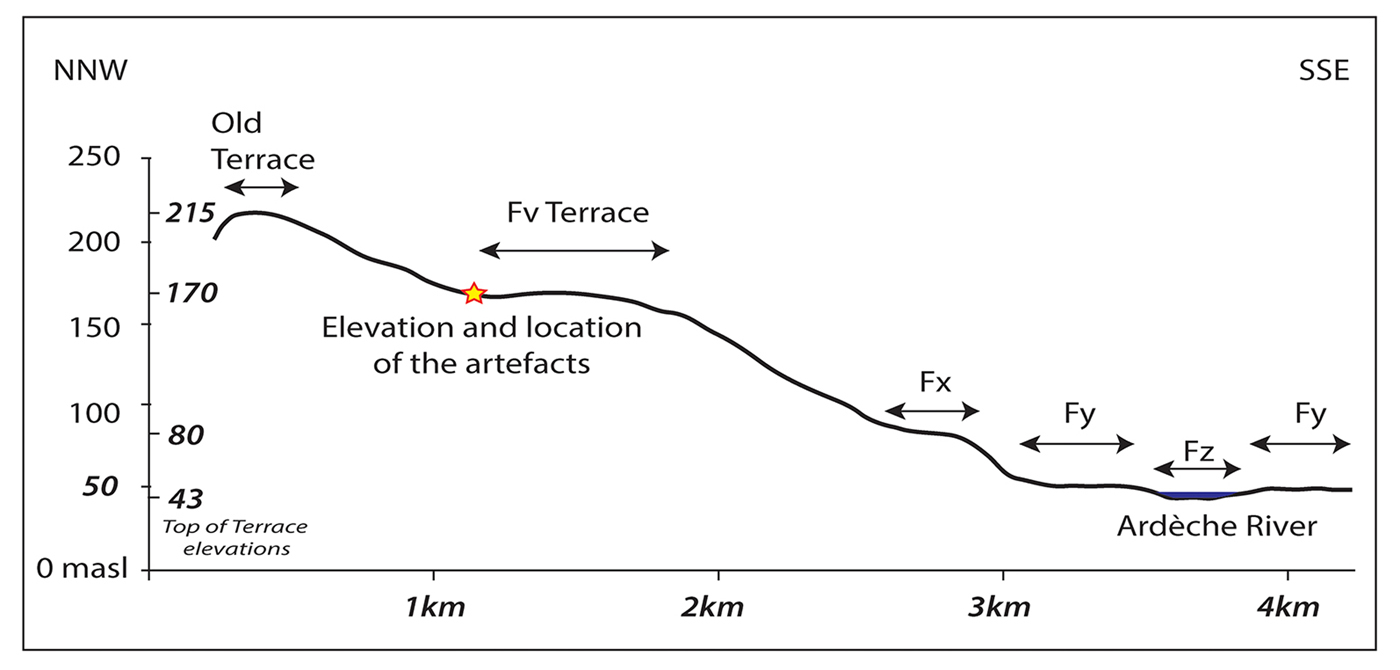

Figure 3. Transverse section through the terraces of the lower Ardèche River (star marks the location of site) (figure by Ludovic Mocochain).

Figure 4. Quartzite large flakes and core (photographs by Marie-Hélène Moncel, illustrations by Angeliki Theodoropoulou).

The artefacts were found in the Ardèche alluvial terraces. Previous studies show four levels of terraces (Labrousse Reference Labrousse1977; Pascal et al. Reference Pascal, Elmi, Busnardo, Lafarge, Truc and Valleron1989), ranging from the present floodplain of the Ardèche River (level Fz) to the highest terrace where the artefacts were located (level Fv). A large plane surface corresponds to the Fv terrace and flanks the pediment.

The artefacts were found on a subhorizontal ledge partially cut by a palaeogully, which is extended by a present-day gully. The formation of this gully is probably polygenic. The upper part is totally dry and appears as a small infilled valley, while downstream it is steep-sided and crossed by episodic flows. Artefacts are not reworked, and show burial by colluviation and pedogenesis (slightly smoothed edges, thin and reddish glossy sheen without impact features of high-mobility processes). Regionally, the Fv terrace corresponds to the Pliocene abandonment surface with an age of two million years (Clauzon Reference Clauzon1982, Reference Clauzon1996), which is correlated with the youngest fossiliferous level of Saint-Vallier (MNQ17 biozone) (Guérin et al. Reference Guérin2004). In the study area, the age of this surface was estimated between 1.94 and 1.77 million years by combined absolute dating and palaeomagnetism (Tassy et al. Reference Tassy, Mocochain, Bellier, Braucher, Gattcceca and Bourlès2013).

How to interpret the discovery of heavy-duty tools on this high terrace

The lithic series is clearly flaked by humans. Their technological features are typical of early Lower Palaeolithic behaviours (Moncel & Ashton Reference Moncel, Ashton, Gallotti and Mussi2018). No similar discoveries have been reported on younger alluvial formations in the same area despite systematic surveys over the past two decades. The stratigraphic position of these artefacts on the side of this high terrace shows that they could not have been introduced by natural processes. Our findings only concern a deposit corresponding to the remains of an alluvial formation dated to before 1.7 million years ago. Evidence of human occupations is later than the first downcutting phase of the palaeogully, which caused the erosion of the Fv terrace. Human occupation was probably contemporaneous with or later than the filling of the palaeogully, as downcutting would probably have destroyed the artefacts along with the Fv terrace. The age of the artefacts presented here is clearly not as early as the formation in which they were found, but nonetheless their location raises questions. They could attest to sporadic traces of early hominid passage from 1.7 million years ago in this part of France, just below an alluvial formation bordering a large plain.

The unique topographical location and the technological features of this discovery highlight the difficulties in interpreting isolated artefacts on high alluvial formations, but also open new avenues of research for dating early European occupations.

Acknowledgements

Surveys were supported by the French Ministry of Culture and the Service Regional de l'Archéologie, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes.