Disadvantage on the basis of race is pervasive (e.g., Larson, Gilles, Howard, & Coffin, Reference Larson, Gillies, Howard and Coffin2007; Paradies, Harris, & Anderson, Reference Paradies, Harris and Anderson2008). In Australia, Indigenous Australians have been marginalised since the arrival of the first fleet in 1788 (Bourke & Cox, Reference Bourke, Cox, Bourke, Bourke and Edwards1994) and continue to face social and institutionalised racial discrimination (Henry, Houston, & Mooney, Reference Henry, Houston and Mooney2004; Mooney, Reference Mooney2003). Racism can be defined as ‘that which maintains or exacerbates inequality of opportunity among ethnoracial groups, and can be expressed through stereotypes (racist beliefs), prejudice (racist emotions/affect) or discrimination (racist behaviours and practices)’ (Berman & Paradies, Reference Berman and Paradies2010, p. 4).

For Indigenous Australians, the effects of racial discrimination can be seen in a variety of outcomes, including poor levels of educational attainment (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2008), reduced earning capacity (ABS, 2006a), difficulties with housing (Beresford, Reference Beresford2001), inferior quality of health care (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Houston and Mooney2004), over-representation within the prison system (ABS, 2009), and significantly lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous Australians (ABS, 2006b). Discrimination also significantly impairs the physical and psychological wellbeing of Indigenous Australians (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Gillies, Howard and Coffin2007; Paradies et al., Reference Paradies, Harris and Anderson2008), with some responding to racial discrimination by withdrawing from society, engaging in drug and alcohol use, and by internalising racism (Mellor, Reference Mellor2004). Clearly, there is a great need to establish equality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians with a focus on putting an end to racism and discrimination.

Bystander Anti-Racism

The possibility of using bystanders to intervene in acts of discrimination has recently led to the investigation of bystander anti-prejudice (e.g., Swim & Hyers, Reference Swim and Hyers1999; Good, Moss-Racusin, & Sanchez, Reference Good, Moss-Racusin and Sanchez2012), and more specifically bystander anti-racism (e.g., Pedersen, Paradies, Hartley, & Dunn, Reference Pedersen, Paradies, Hartley and Dunn2011a; Pedersen, Walker, Paradies, & Guerin, Reference Pedersen, Walker, Paradies and Guerin2011b). Bystander anti-racism can be defined as action undertaken by a witnessing individual (not the target or perpetrator) to challenge and ultimately stop instances of interpersonal or institutionalised racism (Nelson, Dunn, & Paradies, Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011).

As bystander anti-racism involves the average person challenging instances of discrimination, it is especially well placed to target ‘everyday’ racism (Beagan, Reference Beagan2003; Swim, Hyers, Cohen, Fitzgerald, & Bylsma, Reference Swim, Hyers, Cohen, Fitzgerald and Bylsma2003), which occurs at a social or interpersonal level outside the reach of policy (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011). Everyday racism can be understood as disparaging innuendos, acts, beliefs, or attitudes about a given racial group that are encountered on such a regular basis that their offensive and damaging nature is often denied, downplayed, or not recognised by those who are not targets (Bloch & Dreher, Reference Bloch and Dreher2009; Dunn & Nelson, Reference Dunn and Nelson2011; Swim et al., Reference Swim, Hyers, Cohen, Fitzgerald and Bylsma2003).

Outcomes of Bystander Anti-Racism

Aside from the immediate aim to obstruct and stop racial discrimination, one of the suggested key and longer term outcomes of bystander anti-racism is its ability to establish anti-racism norms (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011). Researchers have long reported that people tend to behave in accordance with standards set by others (e.g., Asch, Reference Asch1955, Reference Asch1956; Crandall, Eshleman, & O'Brien, Reference Crandall, Eshleman and O'Brien2002). These standards are referred to as norms and are communicated through social interaction (Cialdini & Trost, Reference Cialdini, Trost, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey1998).

Norms inform us about what behaviours are and are not considered acceptable. Research suggests that hearing just one person express a given opinion or attitude is sufficient to influence the opinions and behaviour of others (Blanchard, Lilly, & Vaughn, Reference Blanchard, Lilly and Vaughn1991). This has implications for the possible effect of bystander action as well as that of bystander inaction. When bystanders speak up, it may be possible to establish anti-racism norms. Yet, on the other hand, bystander inaction means that the prejudiced opinions of the perpetrator are given ‘air time’ and may influence other witnesses and establish or maintain pro-racism norms (Masser & Phillips, Reference Masser and Phillips2003).

Other lines of study indicate that being confronted about racist behaviour triggers feelings of guilt, concern for the welfare of the target, and apologetic responses from perpetrators (Czopp & Monteith, Reference Czopp and Monteith2003). In addition, some researchers have found that being confronted about racist behaviour reduces the likelihood of such behaviour being repeated in the future, as well as a reduction in the prejudice levels of the perpetrator (Czopp, Monteith, & Mark, Reference Czopp, Monteith and Mark2006). Thus, it seems probable that bystander anti-racism may not only provide the basis for anti-racism norms, but may also reduce the likelihood of future racist behaviours.

Finally, the fact that highly prejudiced individuals tend to overestimate social support for their views (e.g., Pedersen, Griffiths, & Watt, Reference Pedersen, Griffiths and Watt2008; Watt & Larkin, Reference Watt and Larkin2010), and are more willing to publicly behave in ways that reflect their prejudices (Miller, Reference Miller1993), implies that bystander anti-racism may be an effective tool for challenging the false consensus beliefs of highly prejudiced individuals. In summary, bystander anti-racism shows promise as a means of effectively challenging racial discrimination. Yet there is limited research that has explored its possible correlates and predictors.

Potential Predictors of Bystander Anti-Racism

As bystander anti-racism can be thought of as a specific form of pro-social behaviour, research on pro-social behaviour is well positioned to suggest potential predictor variables. Furthermore, as attitudes tend to direct behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, Reference Ajzen, Fishbein, Albarracín, Johnson and Zanna2005; Glasman & Albarracin, Reference Glasman and Albarracín2006), research on pro-social attitudes may also be relevant. Variables identified as possibly relevant to bystander anti-racism are discussed below.

National Identity

Social identity theory (SIT, Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986) posits that in social situations we often operate according to our social identity. Tajfel (Reference Tajfel1974) defines this social identity as ‘that part of an individual's self-concept which derives from his [sic] knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the emotional significance attached to that membership’ (p. 69). One's group will from hereon be referred to as the ‘ingroup’, while the ‘outgroup’ refers to a group whose membership one does not share.

As individuals strive to feel good about themselves and their group membership (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986), they are motivated to act positively towards their ingroup. In support of this assumption, many researchers have indeed found that individuals are most likely to help those who belong to their ingroup (Cuddy, Rock, & Norton, Reference Cuddy, Rock and Norton2007; Levine, Prosser, Evans, & Reicher, Reference Levine, Prosser, Evans and Reicher2005; Tarrant, Dazeley, & Cottom, Reference Tarrant, Dazeley and Cottom2009) and to engage in pro-social action on behalf of their ingroup (Klandermans, Reference Klandermans2002; Levine & Thompson, Reference Levine and Thompson2004)

Of course, individuals belong to a variety of social groups. For example, one may identify as a woman, a student, an Australian, and with a great deal of other social groups. SIT proposes, however, that one's behaviour in a given context is influenced by the group identity that is salient in that moment (Terry & Hogg, Reference Terry and Hogg1996). Building on this with respect to bystander anti-racism, it is possible that when racism is expressed, one's racial identity is most salient as such expressions may trigger comparisons between the bystander and the target which make prominent their differences or similarities with respect to race.

Research suggests that Indigenous Australians are not incorporated into the mainstream image of Australian national identity (Sibley & Barlow, Reference Sibley and Barlow2009; Fraser & Islam, Reference Fraser and Islam2000). This implies that the Australian identity may be racially defined, differentiating between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Based on these assumptions, it is feasible that the likelihood of a non-Indigenous Australian engaging in bystander anti-racism on behalf of an Indigenous Australian may depend on their level of national identification. This possibility, however, is yet to be explored.

Collective Guilt

Collective guilt refers to negative feelings which arise from the perception that the actions of other ingroup members are incongruent with the norms or values of the group (Doosje, Branscombe, Spears, & Manstead, Reference Doosje, Branscombe, Spears and Manstead1998). Rather than feeling personally responsible, individuals experience guilt on behalf of the group with which they identify (Iyer, Leach, & Pedersen, Reference Iyer, Leach, Pedersen, Branscombe and Doosje2004; Thomas, McGarty, & Mavor, Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009). Given the history of discrimination and mistreatment of Indigenous Australians by non-Indigenous Australians (Bourke & Collins, 1994), collective guilt may be especially relevant to relations and interactions between these groups.

Collective guilt has been shown to predict support for gay and lesbian anti-violence programmes (Karacanta & Fitness, Reference Karacanta and Fitness2006), the compensation of Indonesians in regards to disadvantage ensuing from Dutch colonisation (Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Branscombe, Spears and Manstead1998), government apology with respect to Australia's history of discrimination towards Indigenous Australians (McGarty et al., Reference McGarty, Pedersen, Leach, Mansell, Waller and Bliuc2005, Studies 1 and 2), reconciliatory attitudes and behaviours within the context of Indigenous Australian history (Halloran, Reference Halloran2007), and reparation attitudes with respect to the Indigenous Chilean history (Brown, Gonzalez, Zagefka, Manzi, & Cehajic, Reference Brown, Gonzalez, Zagefka, Manzi and Cehajic2008). More recently, Pedersen and Thomas (Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012) reported that collective guilt was one of the two emotions most cited by participants when reading about racial discrimination scenarios.

On the other hand, as collective guilt is a self-focused emotion (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach and Crosby2003), some authors argue that it may be limited when it comes to pro-social behaviour (e.g., Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach, Pedersen, Branscombe and Doosje2004; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009). Collective guilt arises from a concern about the involvement of one's group in the mistreatment of another; therefore, it is focused on the self and not the ‘other’. For this reason, it may be that collective guilt can motivate behaviours (such as contribution to financial compensation) that are aimed at reducing the aversive feelings of guilt for an individual, but not those which are aimed at improving the long-term conditions for disadvantaged groups.

Empathic Concern

Empathic concern is the emotional response to the perceived welfare of another (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009; Stephan & Finlay, Reference Stephan and Finlay1999) and specifically involves feeling for another and their situation (Iyer, Leach, & Crosby, Reference Iyer, Leach and Crosby2003). Unlike collective guilt, empathic concern is an other-focused emotion (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach and Crosby2003). As such, it should be especially effective in motivating behaviours that are aimed at restoring equality between advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach, Pedersen, Branscombe and Doosje2004; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009).

As bystander anti-racism involves speaking up to stop the discrimination of another, it seems logical that concern for the welfare of the target might motivate bystanders to act. Supporting this logic, empathic concern has been shown to improve attitudes towards minority (Vescio, Sechrist & Paolucci, Reference Vescio, Sechrist and Paolucci2003) and stigmatised groups (Batson, Chang, Orr, & Rowland, Reference Batson, Chang, Orr and Rowland2002; Batson et al., Reference Batson, Polycarpou, Harmon-Jones, Imhoff, Mitchener, Bednar and Highberger1997), and to be associated with or predict a variety of pro-social behaviours (Eisenberg & Miller, Reference Eisenberg and Miller1987) such as volunteerism (Oswald, Reference Oswald1996), support for equal opportunity and compensatory programmes for African Americans (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach and Crosby2003, Study 2), greater allocation of funds for target support services (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Chang, Orr and Rowland2002), and greater intentions to volunteer in gay and lesbian anti-violence programs (Karacanta & Fitness, Reference Karacanta and Fitness2006).

That empathic concern follows only when one is focused on the other (Harth, Kessler, & Leach, Reference Harth, Kessler and Leach2008; Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach and Crosby2003, Study 2) may be especially pertinent within the bystander anti-racism context. By virtue of being a bystander to instances of racial discrimination, it is possible that one's attention or focus may automatically be drawn to the target (other). It is suggested that this initial focus on the other leads to intergroup comparisons that result in the perception that, relative to the ingroup, the outgroup is disadvantaged (Leach, Snider, & Iyer, Reference Leach, Snider, Iyer, Walker and Smith2002). It is through this process that empathic concern is directed towards members of the outgroup (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009). Supporting the connection between empathic concern and bystander anti-racism, Pedersen and Thomas (Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012) found that when asked about the emotions they would feel when witnessing racial discrimination, empathy for the target was the second most common emotion reported by participants.

Given that in reality, Indigenous Australians are indeed disadvantaged relative to non-Indigenous Australians (e.g. ABS, 2006a, 2006b; 2008), the possibility arises that non-Indigenous Australians may also come to experience empathic concern through recognition of this ‘state’ of disadvantage. As such, empathic concern might be experienced in response to situational factors that make outgroup (relative to ingroup) disadvantage salient, or in response to a general awareness that in comparison to the ingroup, the outgroup is indeed disadvantaged. Whatever the case, although Pedersen and Thomas (Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012) noted the frequent report of empathic concern for the target of discrimination, due to their qualitative focus they did not assess its ability to predict bystander anti-racism. Thus, there are currently no quantitative studies that examine this possible relationship.

Prejudice

Prejudice can be conceptualised as negative opinions, feelings, and attitudes towards the outgroup and its members (Crandall et al., Reference Crandall, Eshleman and O'Brien2002). As mentioned earlier, research suggests that people generally behave in ways that are in line with the attitudes they hold (Ajzen & Fishbein, Reference Ajzen, Fishbein, Albarracín, Johnson and Zanna2005; Glasman & Albarracin, Reference Glasman and Albarracín2006), suggesting that individuals with higher levels of prejudice towards an outgroup might be less inclined to speak up against that group's discrimination. Indeed, prejudice towards an outgroup has been associated with negative attitudes towards outgroup affirmative action programs (Awad, Cokley, & Ravitch, Reference Awad, Cokley and Ravitch2005; Ellis, Kitzinger, & Wilkinson, Reference Ellis, Kitzinger and Wilkinson2002) and a reduced likelihood of providing help to that group (Kluegel & Smith, Reference Kluegel and Smith1983).

Socio-Demographics

Also of interest are the relationships that have been found between prejudice and certain socio-demographic variables. For example, higher levels of prejudice have been significantly correlated with lower levels of formal education (Pedersen & Hartley, Reference Pedersen and Hartley2012), being older (Pedersen, Beven, Walker, & Griffiths, Reference Pedersen, Beven, Walker and Griffiths2004), and right-wing political preference (Hodson & Busseri, Reference Hodson and Busseri2012; Whitley, Reference Whitley1999). Being male has also been linked to greater prejudice levels (Pedersen & Walker, Reference Pedersen and Walker1997), and is related to poorer attitudes toward affirmative action on behalf of minority groups (Kravitz & Plantania, Reference Kravitz and Platania1993). In contrast, however, other research has failed to find a correlation between gender and affirmative action attitudes (Awad et al., Reference Awad, Cokley and Ravitch2005). Also relevant to the present study is the notion that social norms, which prescribe the protection of women (Felson, Reference Felson2000), may allow them to feel more at ease to engage in bystander anti-racism than their male counterparts because they may feel protected from the consequences of doing so.

In addition to the relationship found between age and prejudice, some research has found correlations between age and helping behaviour. Amato (Reference Amato1985) found that older participants were more likely to engage in planned formal helping, defined as providing help in ways that were planned in advance, and given within an organised context (non-profit organisations or community groups, rather than to friends, family or individual strangers). Amato argued that the relationship between age and formal helping was indicative of there being a stage within one's life cycle at which individuals are better equipped to engage in formal helping.

Amato did not, however, elaborate on why a given stage of one's life would have this effect. Based on Amato's definition of planned helping, it is clear that bystander anti-racism would best be described as unplanned or spontaneous helping, as one can never know in advance when racial discrimination will be encountered. There is little research that has investigated the predictors of this form of helping; thus, it is unknown whether this relationship exists with respect to unplanned helping. For this reason, whether a relationship exists between age and bystander anti-racism will be further explored in the present study.

With respect to the socio-demographic variables outlined here, as they have been linked to prejudice, and prejudice has been linked to reduced levels of outgroup helping, it is worth considering whether they might also link directly with bystander anti-racism.

Fear and Anger (Response Emotions)

It has been suggested that contextual factors of discriminatory situations may have a bearing on the likelihood of bystander anti-racism (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011). Supporting this notion, fear of the perpetrator, or more specifically, of retaliation by the perpetrator, has been linked to the reduced likelihood of confronting name-callers in schools (Aboud & Miller, Reference Aboud and Miller2007) and those who express sexism (Swim & Hyers, Reference Swim and Hyers1999). Thus, fear may render action unlikely because the benefits of intervention are outweighed by the costs (Good et al., Reference Good, Moss-Racusin and Sanchez2012; Kowalski, Reference Kowalski1996). Additionally, some authors (e.g., Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011) have also suggested that anger as a response to racial discrimination may motivate engagement in bystander action.

Anger focused research suggests that this emotion is experienced when a situation is deemed unfair (e.g., Batson et al., Reference Batson, Zerger, Kennedy, Nord, Stocks, Fleming and Zerger2007; Mikula, Scherer, & Athenstaedt, Reference Mikula, Scherer and Athenstaedt1998). In addition, as anger results in high levels of arousal, it is an action-oriented emotion, motivating a direct and ‘in the moment’ challenge to the agents responsible for the perceived unfairness (Averill, Reference Averill1983; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009). As racial discrimination is likely to be appraised as unfair, and bystander anti-racism requires that bystanders act immediately in response to instances of racial discrimination, it seems possible that anger may play a very specific role in motivating bystander anti-racism. Supporting this, Pedersen and Thomas (Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012) found that anger towards the perpetrator was one of the most commonly reported emotions with respect to instances of racial discrimination. Whether fear and anger are specifically able to predict bystander anti-racism, however, remains yet to be examined.

Overview of the Present Study

Although there is a large body of literature available with respect to various pro-social behaviours, the specific act of bystander anti-racism remains relatively unexplored (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011). As such there is a lack of direct evidence as to what factors may predict bystander anti-racism. The present study aimed to address this need using an exploratory approach. Specifically, the first aim was to explore whether variables shown to be associated with various pro-social behaviours and attitudes would also be associated with the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism on behalf of Indigenous Australians. Due to the data collection constraints of the present study, bystander anti-racism intentions were measured rather than the behaviours themselves. Although it would be ideal to measure actions rather than intentions, Ajzen's (Reference Ajzen1991) theory of planned behaviour suggests that behavioural intentions do often lead to actual behaviour.

Supporting this position, in a meta-analysis exploring the efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour, Armitage and Conner (Reference Armitage and Conner2001) found that self-reported behavioural intentions were indeed significantly correlated with actual behaviours (r = .47). Similar results have also been found by other authors (e.g., Randall & Wolff, Reference Randall and Wolff1994; Sheeran & Orbell, Reference Sheeran and Orbell1998). Taken together, these studies support the measurement of action intentions where the measurement of actual behaviour is not possible.

The variables included in the present study were national identity, collective guilt, empathic concern, prejudice, socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, political preference, level of education, and the response emotions fear and anger. As briefly touched on above, everyday racism is especially insidious and has to date been difficult to address. Yet, due to the ‘average person’ level at which bystander anti-racism occurs, it is well positioned to target this form of racism. In light of this, an everyday racism type scenario was used in the present study.

The second aim was to ascertain which related variables might predict the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism. Using the independent variables which showed significant initial bivariate correlations with action intentions, a hierarchical multiple regression was used to build equations to predict bystander anti-racism intentions.

Method

Social and Community Online Research Database (SCORED)

The sample was recruited from Murdoch University's SCORED. Individuals must live in Australia and be over 18 years of age to register with SCORED. Only non-Indigenous Australians were eligible to participate in our survey. Individuals who are registered with SCORED receive points for every survey they complete. When they have accumulated a given number of points they are able to redeem their points for a prize, such as a store voucher. Individuals were contacted via an email that informed them that the online survey was open for participation. Participants provided implicit consent by completing and submitting the survey.

Participants and Procedure

One hundred and fifty participants were recruited from the database throughout July and August 2012; however, one participant's data was removed from analysis as they indicated an Indigenous Australian origin, leaving 149 participants. The mean age of the sample was 44 years (SD = 14.37, range = 19–73 years) and there were slightly more female (54.9%) than male participants (45.1%). The majority of participants reported Anglo-Saxon ancestry (75.9%), followed by other European (12.8%) and Asian (6.4%) ancestry, while the remaining five percent indicated they were ‘mixed’. The sample lived predominantly in Western Australia (71.2%), New South Wales (9.4%) and Victoria (7.9%), with the remainder (11.5%) of participants being distributed throughout the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland, South Australia, and Tasmania. 60.4% of those in Western Australia lived in the Perth metropolitan area.

The sample leaned largely towards left-wing (51.1%) as opposed to right-wing politics (24.4%), while 24.5% of participants reported being ‘neither’. The sample was well educated, with 77.8% having completed or at least commenced some form of post-school education. Data collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2010; 2011) show that in 2009, of the Western Australian population aged between 25–64 years, 62% had obtained a non-school qualification, while the 2011 census reported a larger population of males (50.3%) than females (49.7%) in Western Australia. In comparison, the present study's sample contained more females and was more educated than the general population.

Measures

The surveyFootnote 1 consisted of four primary sections that included socio-demographic, social-psychological, bystander anti-racism intentions, and emotion measures. All of the following scales were presented as an online survey via the database website, and in the order in which they are described below. A 7-point scale that ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) was used for the items in each scale, such that higher scores reflect higher levels of each construct. Where such a scoring system was not used, it will be described below.

Socio-demographics

Participants were asked to indicate their age, gender (1 = male, 2 = female), political preference (1 = left, 7 = right), education level (1 = pre-school, 11 = higher degree such as PhD or Masters, part or complete), ancestry/cultural background, and state and city of residence.

National identity

The ingroup identification scale constructed by Leach et al. (Reference Leach, Van Zomeren, Zebel, Vliek, Pennekamp, Doosje, Ouwerkerk and Spears2008) was used to measure participants’ level of national identification. The scale has been shown to be reliable (see Leach et al., Reference Leach, Van Zomeren, Zebel, Vliek, Pennekamp, Doosje, Ouwerkerk and Spears2008, p. 150). Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with various items in the scale. Examples of items used include ‘I feel a bond with Australians’ and ‘I think that Australians have a lot to be proud of’.

Collective guilt

A five-item collective guilt scale was constructed based on that of Doosje and colleagues (Reference Doosje, Branscombe, Spears and Manstead1998). The items were rewritten to reflect the Indigenous Australian/Australian context. Doosje and colleagues found this scale to be reliable (α = .84). Examples of the items used include ‘I feel regret for the harmful past actions of Australians toward Indigenous Australians’ and ‘I don't think that Australians today should feel guilty about the negative things done to Indigenous Australians’.

Empathic concern

The five-item empathic concern scale used by Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Beven, Walker and Griffiths2004) was used to measure the degree to which participants empathised with and were concerned about Indigenous Australians. Some items were slightly reworded for clarity. Pedersen and colleagues found this scale to be satisfactory (α = .69). Examples of the items used include ‘I often empathise with Indigenous Australians’ and ‘I don't have much sympathy for Indigenous Australians’. The empathic concern scale was placed prior to the scenario and the bystander anti-racism intention measure so that it would measure empathic concern with respect to Indigenous Australians specifically, rather than as a response emotion to witnessing discrimination.

Attitudes Towards Indigenous Australians (ATIA)

This scale was also taken from Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Beven, Walker and Griffiths2004), and was used to measure participants’ racism levels towards Indigenous Australians. The ATIA is comprised of 18 items that are a mix of ‘old fashioned’ and ‘modern’ statements, and was found to be very reliable (α = .93). Examples of the items used in the ATIA include ‘Indigenous Australians would be lost without white Australians in today's society’, and ‘Indigenous people work as hard as anyone else’.

Bystander anti-racism intentions

A bystander scenario was adapted from Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Paradies, Hartley and Dunn2011a), and was used to gauge how likely participants were to intervene when witnessing an instance of racial discrimination against Indigenous Australians. The scenario involved a low risk interpersonal context, and aimed to represent a form of racism that one might encounter on a day to day basis (everyday racism). Participants were asked to imagine that they were sitting with colleagues when their discussion turns to Indigenous Australian issues. One colleague states: ‘They mostly are a bunch of lazy bastards’, while the others agree and continue the discussion in a very negative way. Using a 7-point scale that ranged from extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (7), participants were then asked to indicate how likely it was that they would speak up or intervene in the scenario.

Fear and anger

To measure level of fear in response to the scenario, participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with four statements such as ‘This situation makes me feel afraid’. The level of anger in response to the scenario was measured in the same way, with statements such as ‘This situation makes me feel furious’. Both the fear and anger scales were adapted from those used by Mackie, Devos, and Smith (Reference Mackie, Devos and Smith2000), who found them to be reliable (α = .89 and α = .87, respectively). Van Zomeren, Spears, Fischer, and Leach (Reference Van Zomeren, Spears, Fischer and Leach2004) also used a variant of the Mackie et al. (Reference Mackie, Devos and Smith2000) anger scale in their three studies, finding it to be reliable in each (α = .86–.91). Furthermore, Van Zomeren et al. found that anger as measured by this scale was predictive of collective action tendencies, suggesting that it may useful in assessing the relationship between anger and the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism in the present study.

Results

Descriptives

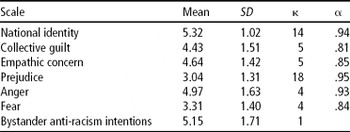

Composite scores ranged from 1–7 and were calculated by averaging item scores for each scale. Higher scores reflect higher levels of the construct. The descriptive statistics for each scale are displayed in Table 1 and include the reliability coefficients, the scale means and standard deviations, and the number of items in each scale (k). Alpha coefficients were very good for all scales.

Table 1 Descriptives For All Scales N = 149

Note. Range for each scale = 1–7, κ = No. of items.

Correlations

Table 2 presents the bivariate correlations among the predictor variables. Most important are the correlations between the predictor variables and the criterion variable (bystander anti-racism intentions).

Table 2 Intercorrelations Among Variables (N = 149)

Note: Pearson product–moment correlation was used; higher scores reflect higher levels (or likelihood) of each variable; Re: gender, 1 = male, 2 = female; Re: political preference, 1 = left, 2 = right; * = p ≤ .05; ** = p ≤ .01; *** = p ≤ .001, all 2-tailed.

Every variable except level of education was significantly correlated with bystander anti-racism intentions. Female participants indicated a greater intention to engage in bystander anti-racism than did males, as did participants who reported lower levels of national identification. Being older, politically left inclined, feeling a greater level of collective guilt about historical wrongdoings, and a greater level of empathic concern toward Indigenous Australians were all associated with a greater likelihood of intervening on behalf of Indigenous Australians. Additionally, and perhaps not surprisingly, participants who reported less prejudice toward Indigenous Australians also indicated a greater likelihood of intervening. Relative to the scenario itself, those who felt greater levels of anger reported a greater intention to intervene. Unexpectedly, however, participants who felt greater fear indicated a greater likelihood of intervening than participants who reported lower levels of fear.

Predictors of Bystander Anti-Racism Intentions

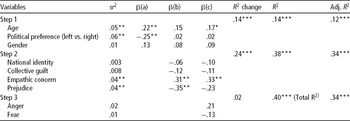

A hierarchical multiple regression equation was employed to explore what proportion of variance in bystander anti-racism intentions could be both uniquely and collectively accounted for by the predictor variables. Only the predictor variables that showed significant correlations with bystander anti-racism intentions were included in the regression equation; thus, education was not used in the equation. As previous research indicates that socio-demographic variables are less predictive of prejudice than social-psychological variables (e.g., Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Beven, Walker and Griffiths2004), socio-demographic variables were entered into step one. Social-psychological variables were entered into step two, and the response emotion variables were entered into step three. The emotion variables were entered last in an effort to identify whether anger and/or fear in response to the scenario predicted bystander anti-racism intentions once all other predictor variables were accounted for. Table 3 presents the bystander anti-racism intention equation.

Table 3 Hierarchical Multiple Regression Equation for Bystander Anti-Racism Intentions (N = 149)

Note: *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001 (all two tailed). β(a) denotes beta weight for variables after step 1; β(b) denotes beta weights for variables after step 2; β(c) denotes beta weights for variables after step 3.

The socio-demographic variables entered on step 1 collectively accounted for a significant 14%, F(3,110) = 6.02, p = .001, of the variance in bystander anti-racism intentions, while age and political preference (i.e., left vs. right) each uniquely accounted for a significant proportion of the variance, 5%, t(110) = 2.49, p = .01, and 6%, t(110) = −2.77, p = .007, respectively. On step 2, the inclusion of the five psychological variables accounted for an additional and significant 24% of the variance, bringing the shared variance to a significant 38%, F(7, 106) = 9.17, p < .001. Of all the variables included at step 2, only empathic concern and prejudice uniquely accounted for a significant proportion of variance, 4%, t(106) = 2.51, p = .01, and 4%, t(106) = −2.57, p = .01, respectively.

On step 3, the increase in shared variance accounted for by fear and anger was non-significant, but the total shared variance was 40%, F(9, 104) = 7.60, p < .001. Cohen (Reference Cohen1988) suggests that a combined effect of this magnitude can be considered large (f 2 = .66). In the final equation only age and empathic concern had significant beta weights, uniquely explaining 2.6%, t(104) = 2.11, p = .04, and 4%, t(104) = 2.64, p = .01, of the variance in bystander anti-racism intentions, respectively. In summary, being older and having a greater level of empathic concern for Indigenous Australians uniquely predicted intentions to engage in bystander anti-racism.

Discussion

The present study had two main aims. The first was to explore whether variables that have previously been associated with pro-social behaviours and attitudes might also be associated with bystander anti-racism on behalf of Indigenous Australians. The second was to ascertain whether the associated variables that were revealed during the exploration of Aim 1 might predict the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism; in other words, what were the strongest predictors. The findings relevant to these aims will now be discussed.

Correlates of Bystander Anti-Racism Intentions (Aim 1)

Social-psychological variables

The finding that participants with a stronger Australian identity reported a lesser likelihood to intervene on behalf of Indigenous Australians supports previous research (Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Rock and Norton2007; Levine et al., Reference Levine, Prosser, Evans and Reicher2005; Tarrant et al., Reference Tarrant, Dazeley and Cottom2009) and an assumption of SIT whereby individuals are less likely to help those who do not belong to their ingroup than those who do (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). On the other hand, why lower levels of national identity were related to greater intention to intervene is not exactly clear. SIT (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986) states that because the groups we belong to are perceived as extensions of ourselves, we are motivated to help those who are similar to us and who belong to our groups in order to derive positive affect about the self.

However, just because one identifies to a lesser extent with being Australian, does not mean that they identified strongly with Indigenous Australians. It is equally feasible that those who identified to a lesser extent with being Australian may have identified to a greater extent with another group (not measured) which was either inclusive of Indigenous Australians, or whose values prescribe pro-social behaviour such as bystander anti-racism. A similar suggestion was made by McGarty and colleagues (Reference McGarty, Pedersen, Leach, Mansell, Waller and Bliuc2005), where the authors argued that at least in Australia, where the national identity construct is complex and even ambiguous, an opinion-based group identity may be more relevant. It is important to note is that although significant, the correlation between national identity and bystander anti-racism intentions was weak, and it is therefore possible that a more relevant group identity would result in a stronger correlation.

In line with previous research, greater levels of collective guilt were associated with a greater likelihood to engage in bystander anti-racism (e.g., Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Branscombe, Spears and Manstead1998; Halloran, Reference Halloran2007; Pedersen & Thomas, Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012), as was greater empathic concern (e.g., Eisenberg & Miller, Reference Eisenberg and Miller1987; Karancanta & Fitness, Reference Karacanta and Fitness2006; Pedersen & Thomas, Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012; Oswald, Reference Oswald1996). In other words, participants who experienced higher levels of guilt on behalf of their ingroup with respect to the past and present mistreatment of Indigenous Australians, and who reported greater levels of concern for the welfare of Indigenous Australians, were more likely to speak up against their discrimination.

Some authors have expressed concern that collective guilt leads to pro-social action that allows for the resolution of feelings of guilt, but not more long-term, possibly more arduous, or even costly forms of pro-social action that is aimed at restoring the balance between those who are advantaged and those who are not (e.g., Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach, Pedersen, Branscombe and Doosje2004; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009). Yet, the positive association between collective guilt and bystander anti-racism intentions in the present study suggests there are distinct societal advantages of collective guilt. As bystander anti-racism involves voicing one's disapproval with racism, it is well positioned to help establish anti-racism norms (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011) that would in the long term help diminish the occurrence of racism, and may also lead to the evolution of more positive attitudes and feelings toward the target group, who in this case are Indigenous Australians.

Relative to this finding, it is interesting to note that, as shown in Table 2, national identity and collective guilt were not correlated. Although there was no prediction made in relation to these two variables, it might be expected that if low levels of Australian national identity were associated with higher levels of bystander anti-racism intentions, these variables might have been related, given that the collective guilt scale involved an Australian verses Indigenous Australian dichotomy. Yet, the lack of such a finding again raises the question of how functional an ‘Australian’ identity is when discussing Indigenous Australian relations, adding weight to the above argument that another group identity is possibly more relevant to the issue of bystander anti-racism at least in regards to Indigenous Australians.

Finally, in support of the attitude-behaviour hypothesis (Ajzen & Fishbein, Reference Ajzen, Fishbein, Albarracín, Johnson and Zanna2005; Glasman & Albarracin, Reference Glasman and Albarracín2006), as well as the findings of previous research (e.g., Awad et al., Reference Awad, Cokley and Ravitch2005; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Kitzinger and Wilkinson2002; Kluegel & Smith, Reference Kluegel and Smith1983), prejudice towards Indigenous Australians was negatively correlated with bystander anti-racism intentions. Those who reported more negative attitudes toward Indigenous Australians indicated that they were less likely to intervene on their behalf when witnessing an instance of discrimination against them.

Response emotion variables

In contrast to the assertions of previous research (Aboud & Miller, Reference Aboud and Miller2007; Swim & Hyers, Reference Swim and Hyers1999), a positive correlation between fear and bystander anti-racism intentions emerged in our sample. That is, greater fear was significantly associated with greater intent to engage in bystander anti-racism. This finding is very much contrary to arguments regarding the effect of cost-benefit appraisals on action which suggest that when the cost of action outweighs the possible benefits, the likelihood of such action is reduced (Good et al., Reference Good, Moss-Racusin and Sanchez2012; Kowalski, Reference Kowalski1996). Attempting to apply this argument would mean that, as participants felt more fearful, the perceived benefits to intervene also increased; yet on the surface this seems unlikely.

Although it is unclear why this relationship emerged, there is a possibility to be considered. Because the scenario was of low risk, it is unlikely that participants felt fear out of concern for their physical safety, yet it is plausible that fear of being judged by one's colleagues may have been what was experienced by participants. We can only speculate that if participants agreed with, or were indifferent about the statements being made, that it would be unlikely that they would feel fear of being judged. However, if one was to disagree with the statements being made, and possibly feel that one ought to speak up, then it is possible that thoughts surrounding how one's colleagues might react to a rebuttal would enter one's mind.

So why might the fear of being judged not only be ineffective at stopping people from speaking up against discrimination, but in fact relate to a greater likelihood of speaking up? If we look at Table 2, the correlation between anger and fear indicates that participants who reported greater levels of anger towards the scenario also indicated greater levels of fear. With caution, we suggest that for fear to work as an obstacle it may perhaps have to be fear of a specific consequence. For example, fear of being physically hurt or of being incarcerated for engaging in illegal behaviour may well deter people from engaging in certain pro-social behaviours, but fear or anxiety about how your colleagues might view you if you challenge their prejudiced views might not. Additionally, higher levels of anger were associated with higher levels of fear. It is possible that fear of judgement in this case was not enough to override the effect of being angered by racism, and as such those people were still more willing to speak up.

Finally, in support of past research (e.g., Pedersen & Thomas, Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012) the correlations between anger and bystander anti-racism intentions were significant. Participants who indicated greater anger in response to the discrimination scenario also reported a greater likelihood of engaging in bystander anti-racism. It has been argued that when individuals evaluate a situation as being unfair, they are likely to experience anger (e.g., Batson, Reference Batson, Zerger, Kennedy, Nord, Stocks, Fleming and Zerger2007; Mikula et al., Reference Mikula, Scherer and Athenstaedt1998) which can motivate them to take action against the unfairness (Averill, Reference Averill1983; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, McGarty and Mavor2009). Although our findings cannot with certainty indicate how participants viewed the scenario with respect to fairness, they do lend strength to the argument that anger could be considered an action-oriented emotion.

Socio-demographic variables

Participants who were older and female reported a greater likelihood of engaging in bystander anti-racism. These findings support previous findings which have found correlations between age and helping behaviour (e.g., Amato, Reference Amato1985), and between gender and attitudes towards affirmative action programs for minority groups (e.g., Kravitz & Plantania, Reference Kravitz and Platania1993). Furthermore, our findings on the relationship between political preference and action build on previous findings regarding the relationship between political preference and prejudice (e.g., Hodson & Busseri, Reference Hodson and Busseri2012; Whitley, Reference Whitley1999).

With respect to the relationship between age and bystander anti-racism intentions, it is also worth noting that our findings expand those of Amato (Reference Amato1985), as he only investigated and found a correlation between age and planned helping behaviour, whereas our results indicate that a correlation also exists between age and unplanned helping behaviour. It is possible that Amato's argument for his finding might also explain the relationship found in the present study; that certain later stages in life better position individuals to help others. However, we would add that rather than being specifically relative to a stage in one's life, an increased likelihood of engaging in bystander anti-racism might instead reflect the fact that older individuals have had a greater range of life experiences and therefore a greater range of life and other skills. These skills may then render them more self-confident than their younger counterparts with respect to their ability to help others and to confront or challenge those with whom they disagree.

Regarding the findings on gender, it may be that our results reflect the concept of cooperative self-interest (Kravitz & Plantania, Reference Kravitz and Platania1993), which stipulates that women are more willing than men to support other marginalised and discriminated against groups due to their belief that establishing equality for others will ultimately make their own battle for gender-based equality easier. We also suggest that women might better understand the experience of being marginalised, such that they experience more empathy for others who are also marginalised. On the other hand, it may be that women reported a greater likelihood to intervene because, unlike men, they felt safeguarded by social norms that frown upon violence and aggression towards women (Felson, Reference Felson2000). With respect to political preference, participants who preference the right are generally more socially conservative, resistant to change, and tend to align with policies which maintain intergroup inequity (Hodson & Busseri, Reference Hodson and Busseri2012; Whitley, Reference Whitley1999). It is thus understandable that a left political preference was associated with a greater intent to engage in bystander anti-racism, while a preference to the right was associated with a lower level of bystander anti-racism intentions.

As level of formal education has often been associated with prejudice (e.g., Pedersen & Hartley, Reference Pedersen and Hartley2012; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Griffiths and Watt2008), and prejudice has both in the present study and in past studies been associated with pro-social behaviour, it seemed reasonable that level of education might also independently relate to bystander anti-racism intentions. This, however, was not the case, as our findings showed no evidence of a correlation between level of education and bystander anti-racism intentions.

In summary, intention to engage in bystander anti-racism was significantly associated with age, political preference, gender, national identity, collective guilt, empathic concern, prejudice, anger and fear.

Predicting Bystander Anti-Racism Intentions (Aim 2)

On step 1 of the hierarchical multiple regression, only age and political preference emerged as unique predictors; however, when the social-psychological variables were entered on step 2, age and political preference were no longer unique predictors. Of the social-psychological variables included, only empathic concern and prejudice significantly accounted for a unique proportion of variance in bystander anti-racism intentions. When anger and fear were added to the equation on step 3, however, the only significant predictors were age and empathy. In other words, being older predicted a greater likelihood of engaging in bystander anti-racism, as did greater empathic concern for Indigenous Australians.

Although some of the included variables did not on any step account for a unique proportion of variance in bystander anti-racism intentions, it is important to note that at every step in the regression, the proportion of variance accounted for by the combination of variables was significant. This indicates that although only age and empathic concern uniquely predict the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism, the remainder of the included variables (political preference, gender, national identity, collective guilt, prejudice, anger, and fear) are nevertheless important. This is further supported by the aforementioned significant correlations. Moreover, the significant beta weights of political preference on step 1, and of prejudice on step 2, indicate that these variables are perhaps more relevant than the non-significant variables, but less so than age and empathic concern.

That age was found to be predictive of bystander anti-racism intentions builds on previous research (Amato, Reference Amato1985) and our earlier findings by demonstrating that age is not only associated with but also predictive of unplanned/spontaneous helping behaviour. As a detailed discussion on age has already taken place above, for reasons of parsimony, we will simply reiterate that as a result of having greater ‘life’ experience, older individuals may be better prepared and therefore more confident in their ability to effectively speak up in everyday racial discriminatory situations. Furthermore, while younger individuals might refrain from speaking up out of concern for how they might be perceived by others (work colleagues in this case), older individuals may be less concerned with the perceptions of others and, therefore, such a concern is unlikely to inhibit them from speaking up. The collection of qualitative data in future research may serve to clarify this finding and either confirm or disconfirm our interpretation.

The finding that one's level of empathic concern can predict one's likelihood of engaging in bystander anti-racism is in line with the findings of previous authors who have explored empathic concern for the homosexual community (Karacanta & Fitness, Reference Karacanta and Fitness2006), for fellow students (Oswald, Reference Oswald1996), and for African Americans (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Leach and Crosby2003, Study 2). It appears that concern for the welfare of another serves as motivation to act in a way that may benefit that person or the group to which they belong. Yet could it be that we measured trait empathic concern rather than empathic concern specifically for Indigenous Australians? Admittedly, this possibility cannot be conclusively ruled out; however, while Pedersen and colleagues (Reference Pedersen, Beven, Walker and Griffiths2004) found that trait empathic concern and prejudice towards Indigenous Australians were weakly correlated (r = −.28), they found that empathic concern specifically for Indigenous Australians, and prejudice toward them was more strongly correlated (r = −.63). As the correlation between empathic concern and prejudice in the present study mirrors that found by Pedersen and colleagues some support is offered to the notion that it was indeed empathic concern for Indigenous Australians specifically, that was measured in the present study.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

There are some limitations to the present study that should be considered. First, although action intentions have been shown to significantly relate to actual behaviour (e.g., Armitage & Conner, Reference Armitage and Conner2001; Randall & Wolff, Reference Randall and Wolff1994; Sheeran & Orbell, Reference Sheeran and Orbell1998), there is nevertheless a possibility that social desirability bias may influence self-reported intentions. In this instance, our ability to measure actual bystander behaviour was limited by the online nature of the present study and therefore, action intentions were the next closest measurable construct as indicated by the literature.

Second, as the present sample was a good deal more educated than the general Western Australian community (ABS, 2010), the sample may not adequately reflect the sentiment held with respect to Indigenous Australians in the general population. Unfortunately, this may be a problem that is inherent to using participant databases where sign-up is voluntary, yet because community response rates continue to decline (Pedersen & Hartley, Reference Pedersen and Hartley2012), participant databases often provide the best access to relatively large samples. On the other hand, the fact that the present sample was well educated does not exclude them from being important. Furthermore, it may be of that individuals with a greater level education are best positioned to engage in bystander anti-racism.

Strengths of the present study include that the present paper responds to the need for more research to be carried out within the specific field of bystander anti-racism. In fact, this study is one of the first to examine the correlates and predictors of bystander anti-racism specifically. This is especially important given that everyday racisms are the forms most often encountered on a daily basis by minority groups (Beagan, Reference Beagan2003; Swim et al., Reference Swim, Hyers, Cohen, Fitzgerald and Bylsma2003), and it is these everyday racisms which bystanders are best positioned to combat as they often occur at an interpersonal or social level (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011).

Future research could explore why age, a socio-demographic variable, emerged as pertinent over and above most of the social-psychological variables; a finding that is in contrast to past research with regard to prejudice (e.g. Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Beven, Walker and Griffiths2004). A focus on qualitative data may help to clarify this. It was suggested that older individuals may be more likely to engage in bystander anti-racism because they are less concerned with how they are perceived by others and because through greater life experience, they may better possess the skills required to successfully intervene. Future research could look to ascertain whether this is in fact the case. As mentioned earlier, it may be that opinion-based identities, such as an activist identity for example, may better relate to bystander anti-racism than did national identity. This possibility could also be explored in the future. Finally, researchers should also aim to replicate the present study with different target groups.

Practical Implications

Understanding the predictors of bystander anti-racism relates to the possibility of increasing its occurrence through targeted intervention. A possible reverse interpretation for our findings regarding age is that younger individuals may not perceive themselves as well equipped enough to intervene in instances of racial discrimination, or to challenge those who they have certain types of relationships with. As such, it is viable that younger individuals could be taught through educational interventions how to effectively communicate with others about issues surrounding racism and other cultures more generally, such that they might feel more confident about engaging in bystander anti-racism (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011). In fact, a few studies have already begun evaluating such programs (Pedersen & Thomas, Reference Pedersen and Thomas2012; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Paradies, Hartley and Dunn2011a) and they appear to be successful.

These educational programs may also address the other predictor that emerged. Reporting greater empathic concern for Indigenous Australians was also predictive of intentions to engage in bystander anti-racism. Educational interventions which involve learning about the cultures and histories of minority groups are likely to improve one's ability to focus on the ‘other’ and as such, increase the experience of empathic concern for the relative group (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Walker, Paradies and Guerin2011b).

Concluding Statements

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that many of the variables associated with pro-social attitudes and behaviours are also associated with the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism specifically. Furthermore, it was revealed that age and empathic concern uniquely predicted the intention to engage in bystander anti-racism on behalf of Indigenous Australians. As racial discrimination has the capacity to cause significant harm to a target (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Gillies, Howard and Coffin2007; Paradies et al., Reference Paradies, Harris and Anderson2008), their group, and to a community as a whole, it is pertinent that ways of effectively reducing racial discrimination are investigated. Bystander anti-racism has the immediate effect of stopping racial discrimination, while possibly also resulting in longer term benefits such as the establishment of anti-racism norms and the reduction of future discriminatory behaviour (Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, Lilly and Vaughn1991; Czopp & Monteith, Reference Czopp and Monteith2003; Czopp et al., Reference Czopp, Monteith and Mark2006; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Dunn and Paradies2011).

The findings from this research may be used to inform the design of educational intervention programs aimed at providing the necessary skills for individuals to feel confident in speaking up against racial discrimination. By increasing the likelihood of bystander anti-racism, closing the gap between the advantaged and disadvantaged may be just that one step closer.