Introduction

Sexual initiation is a key point of transition from childhood to adulthood. Early sexual debut increases exposure to risky sexual activity (Stöckl et al., Reference Stöckl2013), including having older and multiple sexual partners, low use of contraceptives and condoms and contracting sexually transmitted infections, including HIV – especially for girls (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2005, p. 202; Zuilkowski & Jukes, Reference Zuilkowski and Jukes2012). Early sexual debut also increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy, early childbearing and adverse reproductive and health outcomes for adolescents and their offspring (Mmari & Blum, Reference Mmari and Blum2009).

Few studies have examined the effect of sexual debut on schooling, except indirectly in studies on pregnancy and marriage as causes of dropout (Meekers & Ahmed, Reference Meekers and Ahmed1999; Mensch et al., Reference Mensch2001; Madhavan & Thomas, Reference Madhavan and Thomas2005; Grant & Hallman, Reference Grant and Hallman2008; Lloyd & Mensch, Reference Lloyd and Mensch2006; Marteleto et al., Reference Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod2008). Findings from the 2004 National Survey cross-sectional data on adolescents (aged 12–19 years) in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Malawi and Uganda (Biddlecom et al., Reference Biddlecom, Gregory, Lloyd and Mensch2008) showed that girls who had experienced sexual debut were 2–5 times more likely to drop out prior to completing primary school, compared with those who had not initiated sex. For boys, this association was found to be negligible. Similar findings were observed among secondary school students in southern Malawi, where sexual activity among girls, and not boys, was found to be associated with school dropout (Frye, Reference Frye2017). Analysis of longitudinal data from the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS) in South Africa showed that those who engaged in early sex were less likely to complete secondary school (Bengesai et al., Reference Bengesai, Khan and Dube2017). In Kenya, girls’ perceptions of gender equality and how they were treated in school were shown to influence their decision to engage in premarital sex, although no such association was seen among boys (Mensch et al., Reference Mensch2001). In southern Malawi, girls with strong future-oriented goals for schooling, pregnancy and marriage were found to be more likely to abstain from sex; while those already sexually active were interested in fulfilling short-term, and specifically financial, needs (Kazembe, Reference Kazembe2006; Poulin, Reference Poulin2007; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Poulin and Kohler2009), which may lead to dropout.

Sexual activity and school dropout may both be higher among adolescents who have delayed progression through school or who are disaffected with school (Poulin, Reference Poulin2007). Analysis of longitudinal survey data of South African adolescents (Hallman & Grant, 2006) showed that those with delayed enrolment were more likely than those who started on time to become pregnant in school, while those who had repeated a grade prior to becoming pregnant were twice as likely to drop out of school. Other evidence from South Africa suggests that those with higher repetitions are more likely to get pregnant and less likely to re-enrol in school after the pregnancy (Marteleto et al., Reference Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod2006), while those who perform better on literacy and numeracy tests are less likely to become sexually active and drop out (Marteleto et al., Reference Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod2008). In Kenya, students have been reported to have sexual relationships with teachers, either forcibly, as they feared school authority, or in exchange for money or better grades (Mensch & Lloyd, Reference Mensch and Lloyd2011), to continue staying in school. Despite girls performing better than boys in school in southern Malawi, parents’ perceptions and fears of the possibility of schoolgirl pregnancy and their daughters’ inability to ‘resist the temptations of sex’ and ‘focus on school if they are in a sexual relationship’ may also result in their early withdrawal from school (Grant, Reference Grant2012).

The introduction of free primary education in Malawi in 1994 led to high enrolments and a narrowing of the gender gap in schools (Chibwana & Kadzamira, Reference Chibwana and Kadzamira1999). However, the increase in demand for education was not accompanied by improvements in school quality resulting in high repetition rates and slow progression through school (Ravishankar et al., Reference Ravishankar2015). Delayed enrolments and poor progression defined the growing population of overage children, who were most likely to reach adolescence and experience first sex while in primary school. While pre-marital sex is not socially sanctioned in the northern region of Malawi (Hemmings, Reference Hemmings2007), which is the setting for this study, it is common, with first sex experienced at a median age of 17.5 for girls and 18.8 for boys (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn2010). Higher enrolments and educational attainment are considered to have delayed the age of marriage, but with no change in the age at sexual debut, which previously coincided with marriage (Mensch et al., Reference Mensch, Grant and Blanc2011). Earlier puberty also widens the period between puberty and marriage, increasing the likelihood of sexual debut taking place prior to marriage (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2005) when adolescents are often still in school.

This study used longitudinal data from an open cohort of adolescents in Karonga district, northern Malawi, to determine if sexual initiation while enrolled in school is associated with subsequent dropout from primary school, and the extent to which school performance influences this relationship.

Methods

Data for this study originated from a demographic surveillance site (DSS) established in 2002, in a population of around 43,000 individuals from 9000 households in Karonga district, northern Malawi. The surveillance uses community-based informants to collect data on births and deaths continuously, with an annual census also tracking migration of participants (Crampin et al., Reference Crampin2012). Socioeconomic data, including schooling, have been collected from household members (or their proxies) since 2007. Schooling histories are collected for those between the ages of 5 and 30 years, including data on attendance, age (or year) at leaving school, highest level of schooling attended and qualifications attained. Those who had dropped out of school were asked the reason for dropping out and the first reason reported was used as the primary reason. Age (or year) at sexual debut was asked for those 15 years and older in three sexual behaviour survey rounds between 2008 and 2010 (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn2010). Age at menarche was also asked from mid-way through the first round of the sexual behaviour survey. For those with missing data on menarche, responses from subsequent rounds were used. Early onset of menarche was defined as <14 years, corresponding to the 25th centile. Consent to participate in the study was collected from household heads and individual household members as part of the demographic surveillance. For the sexual behaviour survey, individual written informed consent was sought and interviews were conducted in private to ensure confidentiality.

This analysis aimed to understand the association of sexual debut and subsequent primary school dropout, and to examine the extent to which school performance explains this association. In Malawi, primary schools are free; there are eight grades (standards), with the official age of entry being 6 years. Progression from grade to grade depends on satisfactory performance. At the end of primary school, students have to pass an external examination to gain admission into secondary school, which is highly selective, as secondary schools are fewer in number and fee-paying.

Dropout here is defined as the first report of leaving school without completing primary education during the follow-up period and is conditional on being enrolled in school the previous year. Repeat dropouts are rare and have not been included in the analysis. Data on completion were based on self-reports of completing the PSLCE (Primary School Leaving Certificate of Education examination) or inferred from subsequent enrolment into secondary school. Leaving at the end of standard 8 without attaining the certificate was counted as ‘dropping out’ in the analysis.

The analyses utilized the Nelson–Aalen estimation of cumulative incidence (or probability) of dropping out and completion; and the Fine and Gray competing risks model for the cumulative probability of dropping out, with school completion as the competing risk. Competing risks are events that preclude the occurrence of the main event of interest. School completion precludes dropout, leading to non-independent censoring of time to dropout and difficulties in interpreting results from traditional survival analysis methods, such as Kaplan–Meier survival curves and Cox regression models. In contrast, the Nelson–Aalen method and the Fine and Gray model take into account the rate of school completion when estimating the cumulative probability of dropping out and the effect of explanatory variables on this probability expressed on the sub-hazard scale (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Geskus, Witte and Putter2012). The Fine and Gray model assumes proportionality of the effects of the explanatory variables on this scale, which was assessed graphically and formally using the Schoenfeld test (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Geskus, Witte and Putter2012). For simplicity these effects will be referred to as adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs).

Follow-up was set to start at age at school enrolment. Interview dates from annual survey rounds were used to establish the end dates for events reported (dropout, completion and repetition, explained below). Primary and secondary school calendars were used to establish the precise dates for time in school and completion. Follow-up ended once dropout/completion was first observed, at the earliest grade seen beyond standard 8 (end of primary) or when last observed in primary school.

The main exposure of interest was sexual debut. In order to deal with any discrepancies in reporting, sexual behaviour data were examined across three rounds and the youngest age of sexual debut was considered the best estimate of the event. This also limited any possibility of recall bias among respondents at older ages. Since participants were seen annually, sexual debut was included in the model as a time-varying covariate with a one-year lag, where the sexual debut status of an individual in one year was examined for associations with school dropout the following year. For those already sexually active, the reported age of sexual debut was used. For those who last reported being sexually inactive the analysis was censored one year later.

In order to appropriately control for time-varying confounders (Daniel et al., Reference Daniel, Cousens, DeStavola, Kenward and Sterne2013), landmark analysis with the Fine and Gray model was also used to deal with the competing event of school completion. Landmark analysis involves repeating the analyses on overlapping periods of time, starting from different ‘landmark’ ages and including the one-year lagged values of sexual debut as the baseline exposure variable. At each landmark point, those who have already experienced the event (dropout/completion) are excluded, and sexual debut and other time-varying characteristics are assumed to be time-invariant baseline exposures, irrespective of any changes subsequently. Dropout and sexual debut are rare prior to the age of 13 so analyses are presented from age 13 onwards. Girls were censored after the age of 19 and boys after the age of 22, after which no outcomes were observed.

Age-for-grade (or school performance) was calculated as the number of years ahead/behind the current grade. This is a cumulative measure of enrolment and progression through school, though in this population late enrolment is rare (9% at age 7, 1% >age 7) so it is largely a measure of progression. To assess whether school performance modified the relationship between sexual debut and dropout, as well as adjusting for age-for-grade, the landmark analysis was stratified by age-for-grade (those who were ≤1 year, 2 years or 3 or more years overage for their grade). It was hypothesized that there could be interaction between poor progression and sexual debut, with those who were sexually active when already falling behind being more likely to lead to dropout.

To examine whether sexual debut is associated with school performance, time was used to grade repetition as an additional outcome, and age-for-grade adjusted for using one-year lagged values. For this analysis those in Standard 8, where repetitions are high, were excluded, as students may voluntarily repeat the final grade in order to improve their chance of gaining admission into secondary school (Sunny et al., Reference Sunny2017). A standard Cox regression model was used to study the effect of sexual debut on grade repetition, adjusting for age-for-grade.

The proportionality assumption was tested for all covariates using Schoenfeld residuals with some deviation from proportionality observed for age-for-grade and sexual debut. As a result, the hazard ratios reported will be assumed to be averages of time-varying hazard ratios over the follow-up period.

Analyses were carried out with and without adjusting for confounders. Age-for-grade, age at menarche, student–teacher ratio and female-teacher proportions confounded the relationship between sexual debut and dropout so were included in the multi-variable analyses. Mother’s education status was collinear with father’s education status, and hence omitted. Variables that were initially explored but excluded from the multivariable analysis, as they were not associated with dropout for either boys or girls, were sex of the household head and school access to water and electricity. Complete case analysis was carried out and 8% of pupils with missing data were excluded. Most (82%) of these were students attending schools outside the study catchment area, for whom school-level data were not available.

Results

A total of 23,098 participants aged 12–25 years were recruited at baseline in this open cohort, of whom 10,943 (47.4%) were enrolled in primary school when first seen and interviewed more than once across all nine survey rounds (2007–2016). Of these, only a minority were eligible to participate in the sexual behaviour survey (i.e. aged ≥15 years in 2008–10): 3153 (28.8%) who had reported their sexual debut status and age at sexual debut were included in the analysis.

Within the Karonga DSS, the mean age of school entry was 5.9 for both girls and boys. Most children (72%) start school at the official age of 6, with 18% starting early (<6 years) and 9% starting at age 7. Only 1% start older than 7 (maximum age 10 for girls and 13 for boys). Respondents were mostly <17 years, sexually inactive and at least a year or more overage for their grade when first seen (Table 1). Socioeconomic background characteristics were similar for girls and boys. Most participants lived with at least their mother, came from households with more than five members and studied in schools with high student–teacher ratios (>60:1) and low proportions of female teachers (<50%)

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of in-school respondents aged 12–25 years, Karonga district, Malawi, 2007–2016

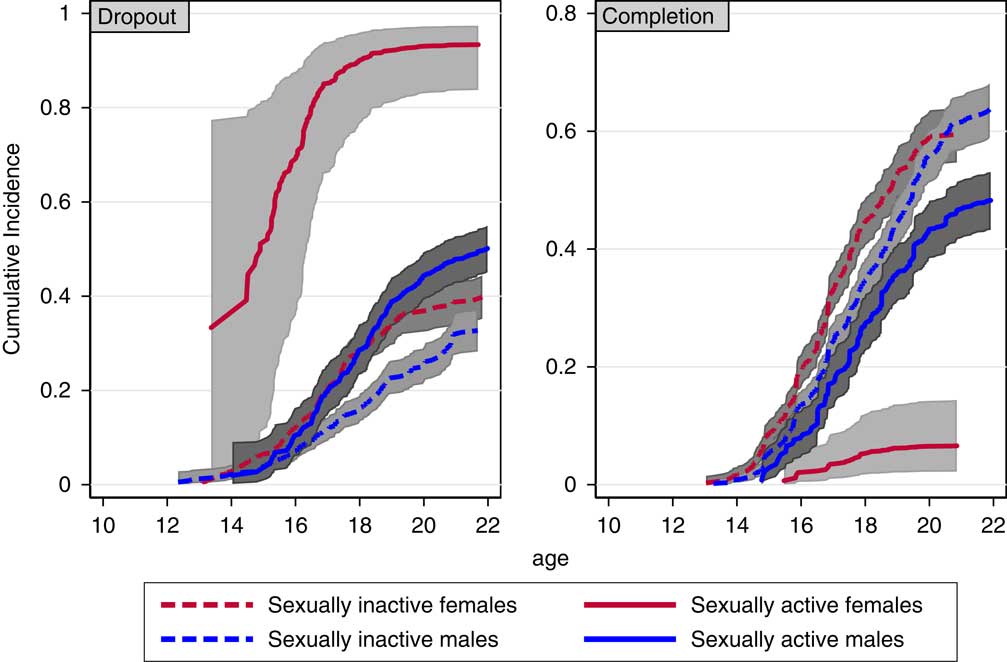

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence (probability) of dropout and completion, respectively, by prior sexual debut status. Sexual debut was associated with dropout for both boys and girls. For girls, those sexually active had a much higher cumulative incidence of dropping out and a lower cumulative incidence of completing school, compared with those who were not sexually active. For boys, dropout was later, less common and less strongly associated with sexual debut. Most of the difference in dropout and completion between girls and boys was among those who were sexually active. Completion levels among sexually inactive girls were similar to those of sexually inactive boys.

Figure 1 Cumulative incidence of school dropout (with completion as a competing event) by one-year lagged sexual debut status among girls and boys, with confidence intervals indicated in shaded areas.

Table 2 shows the association between prior sexual debut status and dropout for girls and boys, with and without adjusting for the wider socioeconomic determinants of school dropout, obtained by fitting the Fine and Gray model. Sexual debut was associated with a 6.4-fold increased hazard of dropout for girls and a 2.6-fold increased hazard for boys. After adjusting for confounders (including age at menarche for girls), this relationship was slightly attenuated for both girls (aHR: 5.27; 95% CI: 4.22–6.57) and boys (aHR: 2.19; 95% CI: 1.77–2.7).

Table 2 Rates and hazard ratios for the association of sexual debut status in the previous year and subsequent school dropout for 3153 primary school students aged 12–25

PY: Person-years (1000s); Rate of school dropout: /1000 PY: HR: hazard ratio; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Analyses were adjusted for age-for-grade, age at menarche (for girls), household asset index, father’s education, living arrangement, household size, number of children below age 6 in the same household, student–teacher ratio and female-teacher ratio.

The adjusted results also show that being overage for their current grade was an important risk factor for dropout, with boys being on average 3.4 years overage for their grade, compared with girls, who were 2.3 years overage for their grade. Every additional year of being overage increased the rate of dropout by 30% for girls and 68% for boys in the adjusted model. Those from better-off households, who were living with both parents, and whose fathers had at least completed primary education, were least likely to drop out of school.

Girls with early menarche (<14 years) were more likely to drop out. None of the school-level factors was associated with dropout for girls after accounting for sexual debut and other confounders. For boys, those living in households with two or more children below the age of six, and studying in schools with low proportions of female teachers, were more likely to drop out of school.

The landmark analysis (Table 3) shows that being sexually active increased the later risk of dropout from landmark age 14 for girls and age 15 for boys. In the crude analysis for girls, the association was stronger at younger ages, but after adjusting for age-for-grade and other confounders there was no consistent pattern by age, with sexually active girls being 3–6 times as likely to drop out of school as their sexually inactive peers at all ages. For boys, those who were sexually active were twice as likely to drop out of school as those who were sexually inactive, and this was constant from age 15.

Table 3 Hazard ratios for school dropout by whether respondents had ever been sexually active by each landmark age, including school completion as a competing event

N: total number in analysis; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; NA: not applicable.

Sexual debut status is categorized as ‘not sexually active’ (reference category) or ‘sexually active’.

The hazard ratio (HR) is adjusted for age-for-grade, age at menarche (for girls), household asset score, father’s education, living arrangement, number of children below age 6 in the same household, household size, student–teacher ratio and female-teacher ratio.

In Table 4, the relationship between sexual debut and dropout has been stratified by age-for-grade and sex for landmark ages 14–16 (the ages for which there were sufficient numbers in the sub-groups). There was no indication that the association between sexual debut and dropout was stronger among those who were more behind in school: in fact, the hazard ratios were lower in this group, but confidence intervals were wide.

Table 4 Hazard ratio for school dropout by prior sexual debut status at each landmark age, by age-for-grade and sex, including school completion as a competing event

N: total number in analysis; HR is the hazard ratio; CI: the confidence interval; NA: not applicable.

Analysis was restricted to age 14+ as sexual activity is rare prior to that, especially among girls. Sexual debut status is categorized as ‘not sexually active’ (reference category) or ‘sexually active’.

The hazard ratio was adjusted for age-for-grade, age at menarche (for girls), household asset score, father’s education, living arrangement, number of children below age 6 in the same household, household size, student–teacher ratio and female-teacher ratio.

Table 5 examines the association between sexual debut and grade repetition for girls and boys. Girls who were sexually active had a higher hazard of subsequently repeating a grade, compared with girls who were not sexually active. This effect remained even after adjusting for prior school performance (age-for-grade in the previous year) and other socioeconomic variables, with no effect being seen among boys.

Table 5 Hazard ratio for the association of prior sexual debut and grade repetition, excluding those in Standard 8

HR: hazard ratio; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

The hazard ratio was adjusted for lagged (from the previous year) estimates of age-for-grade, household asset index, living arrangement, number of children below age 6 in the same household, household size, age at menarche, student–teacher ratio and female-teacher ratio; and time-invariant covariates, including age at menarche and father’s education.

Among those who dropped out before the end of primary, pregnancy (15%) and marriage (45%) were reported as the most common reasons for dropping out among girls (Table 6), irrespective of their sexual debut status the previous year. In contrast, boys mostly reported school- (47%) and household-related reasons (14%) for dropping out of school, with no differences being seen between those who were sexually active or sexually inactive.

Table 6 Self-reported reasons for dropout by lagged sexual debut status and sex

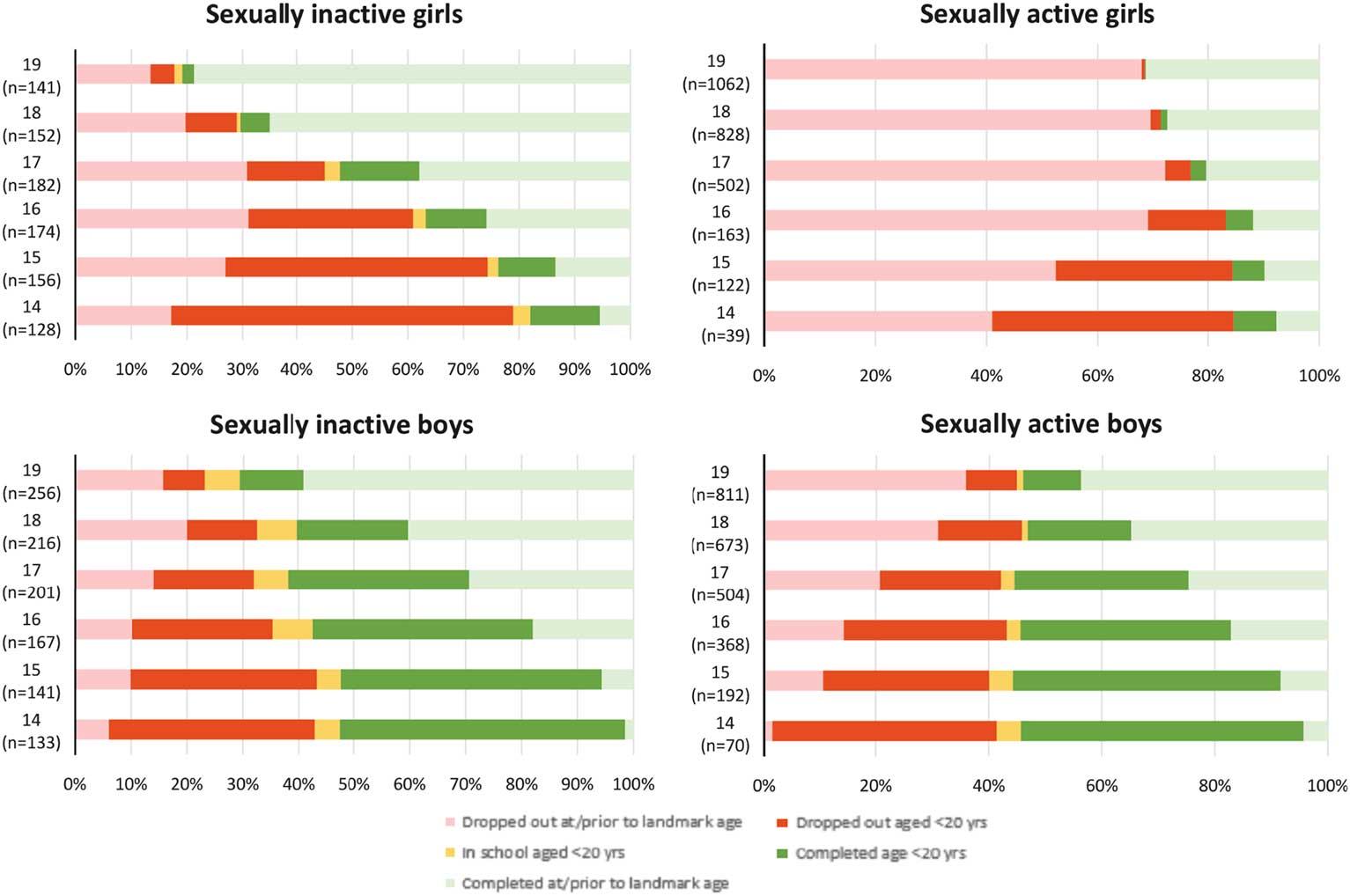

To assess the role of sexual debut on schooling in the wider context, including children who were out of school when first seen, and those already in secondary, the landmark approach was used to descriptively examine the schooling outcomes achieved by age 20, by age at sexual debut. The results are shown in Figure 2. Those who were still sexually inactive at each landmark age had a higher chance of primary school completion than those who were sexually active, and this was much more striking for girls than for boys. For example, for girls who were sexually active by age 16, only 16% completed primary, compared with 70% who were still sexually inactive at 18. For boys the equivalent figures were 55% and 60%, with some still in school.

Figure 2 Sexual debut and school outcomes by age 20, including those out of school and in secondary school. The graphs show the distribution of outcomes among those sexually active or inactive at each landmark age (shown on the y-axes).

Discussion

The results of this study show that sexual activity while still in primary school is an important risk factor for school dropout, with a five-fold risk for girls and a two-fold risk for boys. Falling behind in school was also found to be a strong risk factor for dropout, but the association between sexual activity and dropout was as strong among those who were on track/a year overage as among those who were two or more years overage for their grade. The study’s findings suggest that poor school performance does not drive the association between sexual activity and dropout. However, for girls, being sexually active was found to be associated with subsequent grade repetition, with no effect on performance seen among sexually active boys.

The pathways to dropout are myriad and complex, with pathways for girls being different to those for boys. Unlike previous studies (Biddlecom et al., Reference Biddlecom, Gregory, Lloyd and Mensch2008), this study found that being sexually active is a risk factor for dropout not only for girls, but also for boys, although the effect was stronger for girls. Once sexually active, girls more than boys were likely to repeat a grade and fall behind, which may lead to school disaffection and dropout; or pregnancy/imminent marriage. In contrast, boys face no immediate consequences of poor school performance, either as a cause or as a consequence of sexual activity, although marriage and responsibility for a school-girl pregnancy may be reasons for boys withdrawing/being expelled from school. School performance did not explain the association between sexual activity and dropout, for either boys or girls, which runs contrary to previous findings (Hallman & Grant, 2006; Marteleto et al., Reference Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod2006, Reference Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod2008; Poulin, Reference Poulin2007). This could partly be explained by age-for-grade being a cruder measure of performance than those used elsewhere. In a separate analysis it was found that age-for-grade was not associated with subsequent age at sexual debut for girls or boys, although being overage-for-grade was associated with earlier pregnancy and marriage (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn2018).

Gendered differences in sexual behaviour and school dropout may also be explained by understanding the attitudes and perceptions around adolescent sexual activity among teachers and parents. Studies in southern Malawi have shown that despite girls performing better than boys (Grant, Reference Grant2012) and more boys being sexually active than girls at earlier ages (Munthali et al., Reference Munthali, Chimbiri and Zulu2004; Biddlecom et al., Reference Biddlecom, Munthali, Singh and Woog2007), girls experienced moral policing in schools and were more likely to repeat a grade, face disciplinary action or be suspended by school authorities for being in a relationship or getting pregnant (Frye, Reference Frye2017). Parents who feared the possibility of school-girl pregnancy may also withdraw their daughters from school as a pre-emptive measure (Grant, Reference Grant2012). In contrast, boys were subjected to less severe scrutiny and consequences. Frye’s study in southern Malawi (Frye, Reference Frye2017) found that this incompatibility between sex and schooling was attributed to a pervasive culture within schools and communities that over-emphasized the perception of female vulnerability to sexual relationships and overlooked the role and responsibility of males involved in these partnerships. This was inferred from interviews with teachers, students and parents; and content analysis of school regulations (enforcing disciplinary action on girls who got pregnant), school curricula and media/posters disseminated in schools (‘A real woman puts her future ahead of sexual relationships’; ‘A real woman waits’). Teachers’ attitudes and perceptions of girls’ vulnerability to sexual relationships and the subsequent link to school failure were also prominent. Marriage and pregnancy may also be reasons for leaving school among boys: in the present study 11% of sexually active boys reported these as reasons for dropout. School suspension because of pregnancy has different implications for boys, who may find it easier to re-enrol in school with fewer consequences (Frye, Reference Frye2017), compared with girls who have to bear the social stigma of pregnancy in school, possible withdrawal of parental support and the implications of child care (Madhavan & Thomas, Reference Madhavan and Thomas2005; Lloyd & Mensch, Reference Lloyd and Mensch2006; Grant, Reference Grant2012).

Adolescents’ decisions on schooling may also conflict with their aspirations and genuine desires for marriage and childbearing, which are natural life-course options for girls to transition into after leaving school (Hemmings, Reference Hemmings2007), outweighing the need to perform well in school. Sexual debut is considered a part of the socio-cultural process of finding the right marital partner (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Poulin and Kohler2009), with marriage seen as a means to elevate social status and attain ‘independence, influence, motherhood and respect’ (Hemmings, Reference Hemmings2007, p. 83; Tawfik, Reference Tawfik2003). Poulin’s qualitative study in Malawi examined the social processes and the contractual nature of sexual relationships among school-going adolescents (Poulin, Reference Poulin2007), where engaging in premarital sex is paramount to the process of courtship and the realization of marital aspirations for young people. Access to contraceptives (injectables and condoms) is limited in Malawi, with only a third of unmarried, sexually active adolescent girls between ages 15 and 19 years reportedly getting contraceptives from a government facility (World Health Organization, 2016). However, use of contraceptives in this target group increased from 25.6% in 2000 to 33.7% in 2015 (NSO, 2001; NSO & ICF, 2017). In the present study population, the contraceptive prevalence among women between ages 15 and 49 years was 35% (Dasgupta et al., Reference Dasgupta, Zaba and Crampin2015), with condom use at first sex among those between 15 and 20 years reported at 41.2% among girls and 53.5% among boys (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn2010), which is higher than national-level estimates.

Girls who were sexually inactive also reported pregnancy and marriage as reasons for dropout, which may reflect their desire to marry or get pregnant in the near future or be due to under-reporting of sexual activity. Limitations around reporting of sexual behaviour data are well known (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn2011; Mensch et al., Reference Mensch, Grant and Blanc2011), with girls being more likely than boys to under-report the onset of sexual activity. Another possible study limitation is the lack of data on male puberty. Early menarche, which increases exposure to early sexual debut among girls, has also been previously shown to be a risk factor for early dropout, pregnancy and marriage (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn2010). Lack of data on male puberty, which may be a potential confounder similar to menarche for girls, may explain the effect seen for boys in the present study, which was not seen in previous studies that included data on male puberty (Biddlecom et al., Reference Biddlecom, Gregory, Lloyd and Mensch2008). Qualitative data on the aspirations and intentions of schooling and sexual partnerships may also help us understand the context in which decisions on schooling and sexual relationships operate. In addition, data on peer groups and networks could enhance our understanding of how peer perceptions and behaviour may influence decisions on schooling and sexual behaviour.

Although school performance was not found to be a driving force in the association between sexual debut and dropout, improving the quality of schooling and enabling students to progress and complete school on time would stem the flow of overage students in schools and the conflicts they face when the period of adolescence overlaps with schooling. While sexual activity is a risk factor for schooling it should not be construed as a debarment for young people to engage in sexual activity altogether. Initiating and engaging in sexual activity, irrespective of school enrolment, should be considered a natural, healthy aspect of growing up, forming relationships and building families. Provision of an accurate and relevant sex education curriculum in schools remains imperative. A recent review of curricula in ten eastern and southern African countries, including Malawi, cited concerns around the negative and fear-based content on sexual relationships (UNESCO et al., 2012) and emphasized the need to prioritize issues of safe sex, safe school environments and building critical life skills for young people to negotiate decisions on sex. This would better prepare young people to be ‘ready for sex’ while in school and help them navigate through other life transitions in the future.

In conclusion, in Malawi, sexual activity conflicts with schooling, with sexually active girls more than boys bearing a greater risk of dropping out of school prior to completion. Interventions in schools are needed to both improve the quality of schooling to ensure timely progression and completion before sexual debut, provide sex education in the curriculum and ensure contraception access for young people.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was received from the National Health Sciences Research Committee, Malawi, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This research was funded through research grants from the Wellcome Trust (079828/Z/06/C and 098610/Z/12/Z) and the Economic and Social Research Council-ESRC (ES/L013967/1).