Non-technical Summary

Over the last 50 years, paleobiology has made great strides in illuminating organisms and ecosystems in deep time. Sometimes, these advances have come by interrogating the actual nature of the fossil record itself, specifically, the factors that govern how and why fossils are preserved. Among fossil deposits, none are as enigmatic or as important to our understanding of the history of life as deposits that preserve soft-bodied fossils and thereby retain unusually large amounts of paleobiological information. The great German paleontologist Adolf Seilacher called such deposits “Lagerstätten,” a term now taken to signify paleontological “mother lodes.” These fossil deposits typically represent precise sets of conditions that occur extraordinarily rarely but throughout the geologic record. Some types of these extraordinary deposits, however, represent essentially extinct modes of fossilization, which no longer occur within marine environments. Here, we consider these “anactualistic” styles of fossilization that once were widespread in Earth’s oceans, but only for a geologically brief period of time. We conclude that the circumstances that caused these lost pathways of fossil preservation resulted from specific suites of conditions that dominated ancient oceans during the rise of animal life. The same conditions that promoted anactualistic fossilization may have important implications for the circumstances in which complex life first proliferated in the oceans.

Introduction

Fifty years ago, Seilacher (Reference Seilacher1970) introduced the seminal concept of fossil Lagerstätten to paleontology. Defined as “fossil deposits unusually rich in paleontological information,” fossil Lagerstätten comprise two distinct types of deposits: Konzentrat-Lagerstätten, which are unusual concentrations of fossils, and Konservat-Lagerstätten, which are characterized by unusual fidelity of preservation and include extraordinary preservation of non-biomineralized soft tissues. While the former group holds potential to reveal anatomical and ecological information, unavailable from the “typical” fossil record, the latter group includes some clades of organisms that are entirely soft-bodied and, hence, are otherwise absent from the normal fossil record (e.g., Ediacara and Burgess Shale biotas). Study of fossils and assemblages of soft-bodied organisms thus offers unique insights into the history of life. In this paper, we focus on Konservat-Lagerstätten, here referred to simply as Lagerstätten (singular = Lagerstätte). For the purposes of this review, we use a basic definition of Lagerstätten to refer to deposits that preserve originally non-biomineralized tissues of fossil organisms.

Over the last half century of research, study of Lagerstätten has brought transformative new data to bear in three critical areas: (1) the paleobiology of individual organisms and the implications of key anatomical attributes for animal phylogeny; (2) a fuller picture of the diversity of life present at different intervals of geologic time and the structure of ancient ecosystems; and (3) novel insights into critical transitions in the history of life. Individual fossils often exhibit detailed preservation of soft-bodied morphology and may retain aspects of internal anatomy, including digestive, sensory, circulatory, and nervous systems (e.g., McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Saupe, Lamsdell, Tarhan, McMahon, Lidgard, Mayer, Whalen, Soriano and Finney2016; Bicknell et al. Reference Bicknell, Ortega-Hernández, Edgecombe, Gaines and Paterson2021; Aria et al. Reference Aria, Park, Gaines and Vannier2023). In some cases, structural information at a cellular level is preserved (Scott and Rex Reference Scott and Rex1985; Demaris Reference Demaris2000; McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Orr, Kearns, Alcalá, Anadón and Peñalver2016, Reference McNamara, Zhang, Kearns, Orr, Toulouse, Foley, Hone, Rogers, Benton, Johnson, Xu and Zhou2018; Strullu-Derrien et al. Reference Strullu-Derrien, Kenrick and Knoll2019; Decombeix et al. Reference Decombeix, Harper, Prestianni, Durieux, Ramel and Krings2023). Due to the extraordinary level of detail retained, fossils of soft-bodied organisms have yielded phenomenal insights for paleobiology by greatly extending the temporal ranges of many lineages, by revealing the existence of high-ranking taxonomic groups (i.e., phyla, classes) that have become extinct (Erwin et al. Reference Erwin, Laflamme, Tweedt, Sperling, Pisani and Peterson2011), and through preservation of extraordinary anatomical information that informs phylogenetic study and continues to refine our understanding of the fundamental structure of the tree of animal life. In addition, Lagerstätten include organisms lacking biomineralized tissues and thus preserve components of diversity that are absent from typical fossil deposits, which are composed of shells, teeth, and bones. As such, Lagerstätten have contributed greatly to understanding ancient ecosystems from fossil records that, in many cases, are far more complete than typical fossil deposits. The position of some Lagerstätten in time and in space has furthermore helped to frame the modern understanding of many critical transitions in the history of life, including the origins of complex ecosystems (Droser and Gehling Reference Droser and Gehling2015), the initial colonization of land by invertebrates (Strullu-Derrien et al. Reference Strullu-Derrien, Kenrick and Knoll2019), and the theropod–avian transition (Chiappe Reference Chiappe2009).

As originally recognized by Seilacher (Reference Seilacher1970) and Seilacher et al. (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985), Lagerstätten encompass many modes of exceptional preservation and represent many disparate environments and mechanisms of formation. Seilacher et al. (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985) considered three key environmental factors to be important in the genesis of exceptional fossil deposits: obrution, stagnation (anoxia), and microbial sealing. Subsequent research has demonstrated that each of these attributes are critically important at various points along a continuum of exceptional preservation. Intensive research, however, has also demonstrated that these three factors—alone or in combination—are insufficient to trigger the preservation of soft tissues and that other causal mechanisms are therefore required. Indeed, the mechanisms of preservation underpinning many types of Lagerstätten remain enigmatic and are the subject of intensive study and debate. For this reason, as well as the great rarity of these deposits, early research tended to view Lagerstätten as curiosities of the fossil record, outliers that could represent rare, isolated environmental settings, in contrast to more normal habitats represented in the “typical” fossil record (Briggs Reference Briggs2023).

While emphasizing the great rarity of Lagerstätten in the fossil record, Seilacher and colleagues (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985) also noted that these deposits are not distributed evenly in geologic time but exhibit a concentration in late Neoproterozoic and earliest Phanerozoic open-marine deposits, with a second, smaller concentration of exceptional preservation in restricted marine settings of the Jurassic (see also Allison and Briggs Reference Allison and Briggs1993). More recent work has revealed a third concentration of deposits from terrestrial settings of Paleogene and Neogene age (Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Martindale, Schiffbauer, Creighton and Bogan2019). In the last several decades of research, these patterns have become more robust as the discovery and documentation of new Lagerstätten and understanding of their occurrence and distribution have become priorities for paleobiology (Allison and Briggs Reference Allison and Briggs1993; Butterfield Reference Butterfield1995; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017). In particular, the long-standing problem of the Ediacaran–early Phanerozoic “taphonomic window” (Allison and Briggs Reference Allison and Briggs1993; Orr Reference Orr2014) in open-marine settings has remained a topic of much debate.

In this paper, we focus on the marine record of fossil Lagerstätten in order to specifically address the issue of widespread exceptional preservation during the early history of complex life. We briefly review some of the major types of marine Konservat-Lagerstätten, with emphasis on the geologic circumstances of their occurrences, and consider the problem of the concentration of these deposits in open-marine settings of the Ediacaran and early Paleozoic. We argue that the circumstances that promoted the exceptional fossil record during the Ediacaran–Early Ordovician were widespread in global marine environments, a condition fundamentally unlike those of other types of Lagerstätten, and that the “anactualistic” circumstances (e.g., absent from similar environments today) responsible for exceptional preservation during this interval would have had an impact on the trajectory of the early diversification of animals.

Large-Scale Controls on Exceptional Preservation

Exceptional preservation of non-biomineralized soft tissues occurs across a spectrum of environments represented in the rock record (Seilacher Reference Seilacher1970; Seilacher et al. Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985). As a result, the taphonomic mode of soft tissue preservation, that is, the manner in which nonmineralized tissues are preserved—replicated by mineral phases (e.g., pyrite, calcium phosphate) or conserved as carbonaceous organic remains (e.g., in mudstones)—exhibits considerable variation (Clements and Gabbott Reference Clements and Gabbott2022). Similarly, biostratinomic factors play a leading role in facilitating exceptional preservation, but they too vary widely among different settings where Lagerstätten form (Brett and Baird Reference Brett and Baird1986; Behrensmeyer et al. Reference Behrensmeyer, Kidwell and Gastaldo2000). Accordingly, in their original classification, Seilacher and colleagues recognized that Lagerstätten are most meaningfully classified based on circumstances of their geologic occurrence, which reflect both pre- and postburial factors (biostratinomy and fossil diagenesis) that led to exceptional preservation in each case.

Seilacher et al. (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985) further classified the deposits according to the relative influences of three physical, chemical, and biological factors considered important in their genesis: obrution, stagnation (anoxia), and microbial sealing. Over the last 50 years, research has made great strides in understanding each of these factors. The rise of experimental taphonomy in the investigation of decay (Murdock et al. Reference Murdock, Gabbott, Mayer and Purnell2014; Sansom Reference Sansom2014; Clements et al. Reference Clements, Purnell and Gabbott2022) and exceptional preservation (Briggs and Kear Reference Briggs and Kear1993b; Briggs Reference Briggs1995; McNamara Reference McNamara2013; McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Briggs, Orr, Gupta, Locatelli, Qiu, Yang, Wang, Noh and Cao2013; Briggs and McMahon Reference Briggs and McMahon2016; Alleon et al. Reference Alleon, Bernard, Le Guillou, Daval, Skouri-Panet, Kuga and Robert2017; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017; Purnell et al. Reference Purnell, Donoghue, Gabbott, McNamara, Murdock and Sansom2018; Slater et al. Reference Slater, Ito, Wakamatsu, Zhang, Sjövall, Jarenmark, Lindgren and McNamara2023), as well as a focus on intensive, fine-scale sedimentologic and geochemical investigation of Lagerstätten (Raiswell et al. Reference Raiswell, Newton, Bottrell, Coburn, Briggs, Bond and Poulton2008; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Hammarlund, Hou, Qi, Gabbott, Zhao, Peng and Canfield2012c; McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Orr, Alcalá, Anadón and Peñalver2012; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Briggs, Hammarlund, Sperling and Gaines2013; Cotroneo et al. Reference Cotroneo, Schiffbauer, McCoy, Wortmann, Darroch, Peng and Laflamme2016; Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016), have brought new understanding to the genesis of these deposits and thus has helped to resolve the context and ecological significance of exceptional fossil assemblages.

Obrution, the rapid burial of fossils in sediments or volcanic ash, is an essential first step in a great majority of cases of exceptional preservation. Not only does rapid burial halt physical processes of disarticulation (Brett and Baird Reference Brett and Baird1986), but it can also promote changes in chemical environment that slow the processes of decomposition (Schiffbauer et al. Reference Schiffbauer, Xiao, Cai, Wallace, Hua, Hunter, Xu, Peng and Kaufman2014), and it can create isolated environments for fossil diagenesis and for the mineralization, molding, or stabilization of organic tissues (Darroch et al. Reference Darroch, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Briggs2012; McCoy Reference McCoy2014).

The role of anoxia (stagnation) in exceptional preservation in subaqueous environments has been the subject of intensive study. Experimental work quickly established that anoxia alone is insufficient to cause soft-bodied preservation, as microbial decomposition via anaerobic pathways is capable of complete destruction of soft tissues (Allison Reference Allison1988a). Although anoxia precludes bioturbation and scavenging of buried carcasses and slows rates of microbial decomposition, the major contribution of anoxia to exceptional preservation is that it allows for the activity of anaerobic pathways of microbial respiration that can promote the rapid growth of authigenic minerals that may replicate soft tissues with high fidelity (Allison Reference Allison1988b; Briggs Reference Briggs2003). The specific circumstances that favor mineralization of soft tissues, as well as those that favor the preservation of primary organic remains, are described later. Research in recent decades has also made clear that, while some types of aqueous soft-bodied preservation require anoxia in the benthic environment (Butterfield Reference Butterfield1995; Gaines and Droser Reference Gaines and Droser2010), others may occur in anoxic burial environments beneath weakly oxygenated bottom waters (e.g., Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Briggs and Gaines2011, Reference Farrell, Briggs, Hammarlund, Sperling and Gaines2013; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Martindale, Schiffbauer, Creighton and Bogan2019, Reference Muscente, Vinnes, Sinha, Schiffbauer, Maxwell, Schweigert and Martindale2023). At a larger scale, research in recent decades has shown that atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels did not reach modern concentrations until after the colonization of land by plants in the mid-Paleozoic (Dahl et al. Reference Dahl, Hammarlund, Anbar, Bond, Gill, Gordon, Knoll, Nielsen, Schovsbo and Canfield2010). Relatively low oxygen concentrations during the Neoproterozoic and early Paleozoic led to widespread anoxic and suboxic marine settings on the continental shelves (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Lyons, Young, Kump, Knoll and Saltzman2011; Saltzman et al. Reference Saltzman, Edwards, Adrain and Westrop2015), a factor now broadly recognized as significant in promoting exceptional preservation during this critical interval in the history of life (Gaines Reference Gaines, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017). It is also widely recognized that the majority of the marine record comes from epicontinental seas, which are prone to restriction and oxygen stress, particularly during greenhouse intervals (Peters Reference Peters2007; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Martindale, Schiffbauer, Creighton and Bogan2019).

“Sealing” by phototrophic microbial mats or by heterotrophic microbial biofilms that may rapidly form over decaying carcasses has also been demonstrated to play a significant role in the preservation of soft tissues, as originally hypothesized (Seilacher et al. Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985; Iniesto et al. Reference Iniesto, Laguna, Florin, Guerrero, Chicote, Buscalioni and Lopez-Archilla2015). Sealing is particularly important in settings where rapid burial is not favored, and its activity may have multiple chemical effects. Biofilms may serve to isolate the chemical environments around decaying carcasses, establishing and/or maintaining chemical gradients favorable to early diagenetic mineralization or, in some cases, trapping and concentrating ions liberated from carcasses or from sediments, and thus favoring the precipitation of minerals around soft tissues (Briggs and Kear Reference Briggs and Kear1993a; Wilby et al. Reference Wilby, Briggs, Bernier and Gaillard1996; Varejão et al. Reference Varejão, Warren, Simões, Fürsich, Matos and Assine2019).

Fossil Lagerstätten in the Marine Realm

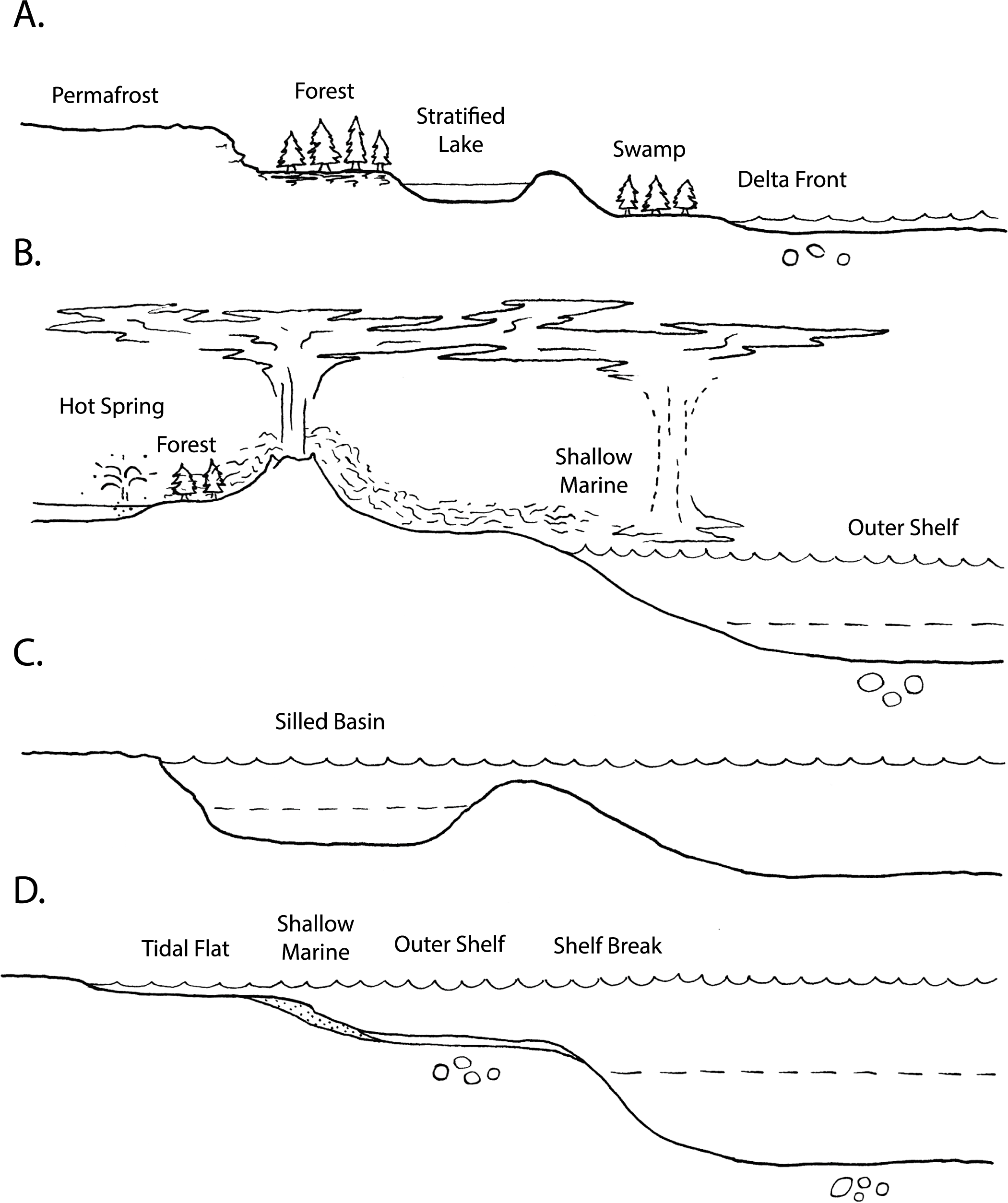

In the following sections, we briefly review some of the primary marine settings in which exceptional preservation occurs (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Figure 1. Environmental settings of fossil Lagerstätten, after Seilacher et al. (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985). A, Terrestrial settings, including delta front transitional setting at right. B, Terrestrial and marine settings of volcanic-associated Lagerstätten. C, Silled/restricted marine basin environments. D, Marine settings of Lagerstätten. The position of the oxycline in B–D is indicated by dashed lines. Circles indicate loci of concretion formation.

Table 1. Marine Konservat-Lagerstätten, arranged by environmental setting and mode of preservation. Blue highlights indicate “anactualistic” modes of preservation (Seilacher et al. Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985).

Deep Marine

Within the marine realm, Lagerstätten are particularly well represented in deep-marine settings characterized by oxygen deficiency, including outer shelf, shelf break, and restricted/silled basin environments (Fig. 1C,D). These settings typically lie near but below the storm wave base, are dominated by mudstones, and may be subject to periodic obrution events resulting from storm wave disturbance of sediments higher on the slope. In these settings, three major modes of preservation occur: pyritization, phosphatization, and organic preservation. Molding of soft tissue anatomy, including via the remineralization of volcanic ash as described later, is also known from deep-marine settings.

Pyritization

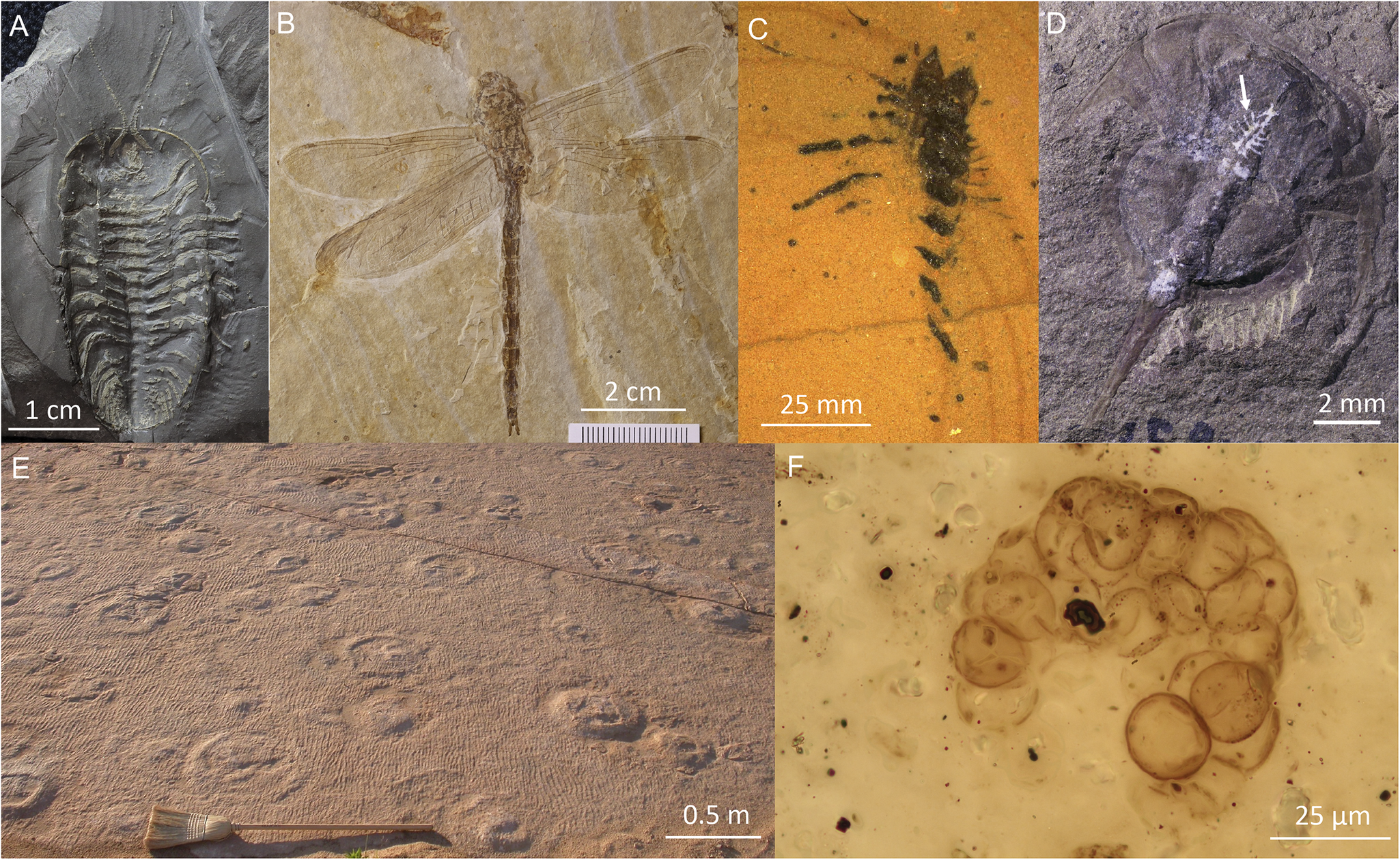

Pyritization as a primary mode of fossilization occurs where soft tissues are rapidly replicated in pyrite, as best known from Beecher’s Trilobite Bed (Ordovician, New York), and Hunsrück (Devonian, Germany) (Raiswell et al. Reference Raiswell, Newton, Bottrell, Coburn, Briggs, Bond and Poulton2008; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Briggs, Hammarlund, Sperling and Gaines2013; Fig. 2A). In these deposits, pyrite is the primary agent responsible for capturing gross soft tissue morphology, often in three dimensions, and may also coat or replicate originally biomineralized tissues (e.g., trilobite cuticle; Farrell Reference Farrell, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014). Because soft tissues rapidly collapse into two dimensions and are completely lost to decay on a timescale of weeks (Briggs and Kear Reference Briggs and Kear1993a), pyritization of soft tissues in three dimensions must occur before collapse.

Figure 2. Examples of exceptional preservation from selected marine and transitional fossil Lagerstätten. A, Pyritized trilobite (Holotype of Triarthrus eatoni) from Beecher’s Trilobite Bed (Ordovician, New York), Yale Peabody Museum specimen number YPM IP 000219. B, Phosphatic preservation of a dragonfly (taxon indet.) from the Solnhofen Lagerstätte (Jurassic, Germany), Yale Peabody Museum specimen number YPM IP 428805. C, Three-dimensional preservation of the arthropod Aquilonifer spinosus as dark-colored calcite against lighter-colored concretion matrix from the Herefordshire Lagerstätte (Silurian, U.K.), Oxford Museum of Natural History specimen number OUMNH C.29695. D, Moldic preservation of the horseshoe crab Euproops danae in siderite concretion from the Mazon Creek Lagerstätte (Carboniferous, Illinois), including preserved neural tissues (arrow), Yale Peabody Museum specimen number YPM IP 168040. E, Bedding surface with multiple scyphozoan medusoids preserved as casts and molds in tidal flat sandstones of the Elk Mound Group (Cambrian, Wisconsin). F, Photomicrograph of organic walled microfossils entombed in silica from cherts of the Fifteenmile Group (Tonian, ca. 800 Ma, Yukon, Canada). Images courtesy of D. Briggs and J. Utrup (A–C); R. Bicknell (D); J. Hagadorn (E); P. Cohen (F).

Remarkable anatomical detail may be captured via pyritization, including the limbs, gills, and eggs of arthropods and the tube feet of asteroids (Farrell Reference Farrell, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014; Siveter et al. Reference Siveter, Tanaka, Farrell, Martin, Siveter and Briggs2014). Pyrite forms in the early burial environment due to the activity of microbial iron reduction, which liberates Fe2+ to solution by reduction of Fe oxides from sediments, and microbial sulfate reduction, which transforms aqueous SO42− from seawater into H2S−. These by-products of microbial respiration react to form iron monosulfides, which are subsequently recrystallized to pyrite (FeS2). The pyritization of soft tissues requires an anoxic burial environment with iron-rich pore-waters and carbon-poor sediments that focus microbial sulfate reduction around freshly buried carcasses (Farrell Reference Farrell, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014). As pyritization requires both anoxic pore-water conditions and a steady supply of seawater sulfate during fossilization, it typically occurs in dysoxic outer shelf settings where the diffusion of oxygen into the shallow burial environment is limited by low bottom water concentrations, but the diffusion of sulfate into pore-waters is unimpeded and thus not limiting to sulfate reduction (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Briggs, Hammarlund, Sperling and Gaines2013). Thus, the processes of pyritization require anoxic pore-waters and shallow burial conditions, but may occur under weakly oxygenated bottom waters (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Briggs and Gaines2011).

It has recently been demonstrated that, under the constraints described earlier, the conditions for pyritization of soft tissues were optimized in Beecher’s Trilobite Bed by the recycling of sedimentary pyrite (Raiswell et al. Reference Raiswell, Newton, Bottrell, Coburn, Briggs, Bond and Poulton2008). There, early diagenetic pyrite-bearing sediments were eroded from the seafloor and entrained in turbidity currents that then swept up and buried soft-bodied animals. During transport, oxidation of some fraction of sedimentary pyrite in seawater formed labile Fe-(oxy)hydroxides, which were readily re-reduced shortly after deposition, resulting in particularly high iron concentrations of pore-waters in the freshly deposited sediment (Raiswell et al. Reference Raiswell, Newton, Bottrell, Coburn, Briggs, Bond and Poulton2008). The localization of sulfate reduction around soft tissues of animals then generated H2S−, which rapidly reacted with dissolved Fe2+ to form pyrite coatings around soft tissues (Briggs et al. Reference Briggs, Bottrell and Raiswell1991).

Soft tissue replication in pyrite also commonly occurs as an auxiliary mode of preservation in many other types of Lagerstätten; in these cases, pyrite replicates specific, limited aspects of soft-bodied anatomy in association with another primary mode of preservation (Burgess Shale–type preservation, phosphatization, molding in concretions). Because it is a common early diagenetic product in marine sediments, pyrite may also be found in association with soft-bodied fossils without capturing any morphological information; however, unless pyrite replicates specific aspects of soft-bodied anatomy, such pyrite should be considered purely incidental to preservation.

Phosphatization

Exceptional preservation via phosphatization, like pyritization, generally occurs in low-oxygen settings, close to the boundary of anoxic and dysoxic benthic environments. Phosphatized fossils may occur in three dimensions in massive phosphates (e.g., Doushantuo, Neoproterozoic, South China; Xiao and Knoll Reference Xiao and Knoll2000) or in carbonate concretions (e.g., Orsten, Cambrian, Sweden; Maas et al. Reference Maas, Braun, Dong, Donoghue, Müller, Olempska, Repetski, Siveter, Stein and Waloszek2006), or as two-dimensional compressions (Fig. 2B) in black, organic-rich shales characterized by low net sedimentation rates and periodic obrution events (e.g., Ya Ha Tinda, Triassic, Canada; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Martindale, Schiffbauer, Creighton and Bogan2019). Phosphatized compression fossils may also occur in restricted inter-reef settings in carbonate muds (Wendruff et al. Reference Wendruff, Babcock, Kluessendorf and Mikulic2020; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Schiffbauer, Jacquet, Lamsdell, Kluessendorf and Mikulic2021; Pulsipher et al. Reference Pulsipher, Anderson, Wright, Kluessendorf, Mikulic and Schiffbauer2022).

Phosphate (PO43−) is an essential nutrient in seawater that is rapidly taken up by phytoplankton and supplied to sediments as organic matter. It is also delivered to sediments by sorption onto iron oxides in the water column. In anoxic sediments, microbial reduction reactions liberate phosphate from both these sources to solution (Paytan and McLaughlin Reference Paytan and McLaughlin2007). Phosphatization of soft tissues is favored by low-pH settings in the shallow burial environment at the anoxic–dysoxic transition in sediments where the precipitation of calcium phosphates as hydroxyapatite is favored over the precipitation of calcium carbonate (Allison Reference Allison1988b; Briggs and Wilby Reference Briggs and Wilby1996; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Hawkins and Xiao2015). Low sediment accumulation rates and elevated primary productivity favor the enrichment of PO43− in sediments, and restricted marine basins, including silled basins or restricted foreland basins (Fig. 1C), can serve as phosphate traps (Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Hawkins and Xiao2015). High concentrations of sedimentary phosphate, however, are lacking in many instances of soft tissue phosphatization, suggesting that soft tissues themselves contributed phosphate for mineralization (Briggs and Wilby Reference Briggs and Wilby1996; McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Orr, Kearns, Alcalá, Anadón and Molla2009, Reference McNamara, Orr, Alcalá, Anadón and Peñalver2012). Indeed, many instances of phosphatization are restricted to specific tissue types (Butterfield Reference Butterfield2002; McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Orr, Alcalá, Anadón and Peñalver2012). While reduced pH around decomposing carcasses certainly plays an important role in calcium phosphate mineralization (Briggs and Wilby Reference Briggs and Wilby1996), recent experimental work has shown that tissue-specific phosphatization cannot be explained by pH gradients within decomposing carcasses. Because individual organs do not have unique pH trajectories during decay, tissue-specific phosphatization is more likely related to primary tissue composition (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Purnell and Gabbott2022).

Spectacular examples of phosphatized soft tissues, including the muscle architecture of Devonian fish (Trinajstic et al. Reference Trinajstic, Briggs and Long2022) and the internal tissues of Jurassic invertebrates (Wilby et al. Reference Wilby, Briggs, Bernier and Gaillard1996), occur within calcium carbonate concretions from deep-marine environments. The formation of concretions may aid in the phosphatization process via sealing (McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Young and Briggs2015a,Reference McCoy, Young and Briggsb) or through development of low-pH microenvironments inside fossil carcasses (McNamara et al. Reference McNamara, Orr, Alcalá, Anadón and Peñalver2012; Trinajstic et al. Reference Trinajstic, Briggs and Long2022). Such internal microenvironments may also promote phosphatization and may also occur as a secondary mode of preservation inside guts or other internal organs (Butterfield Reference Butterfield2002).

Organic Preservation: Burgess Shale–type

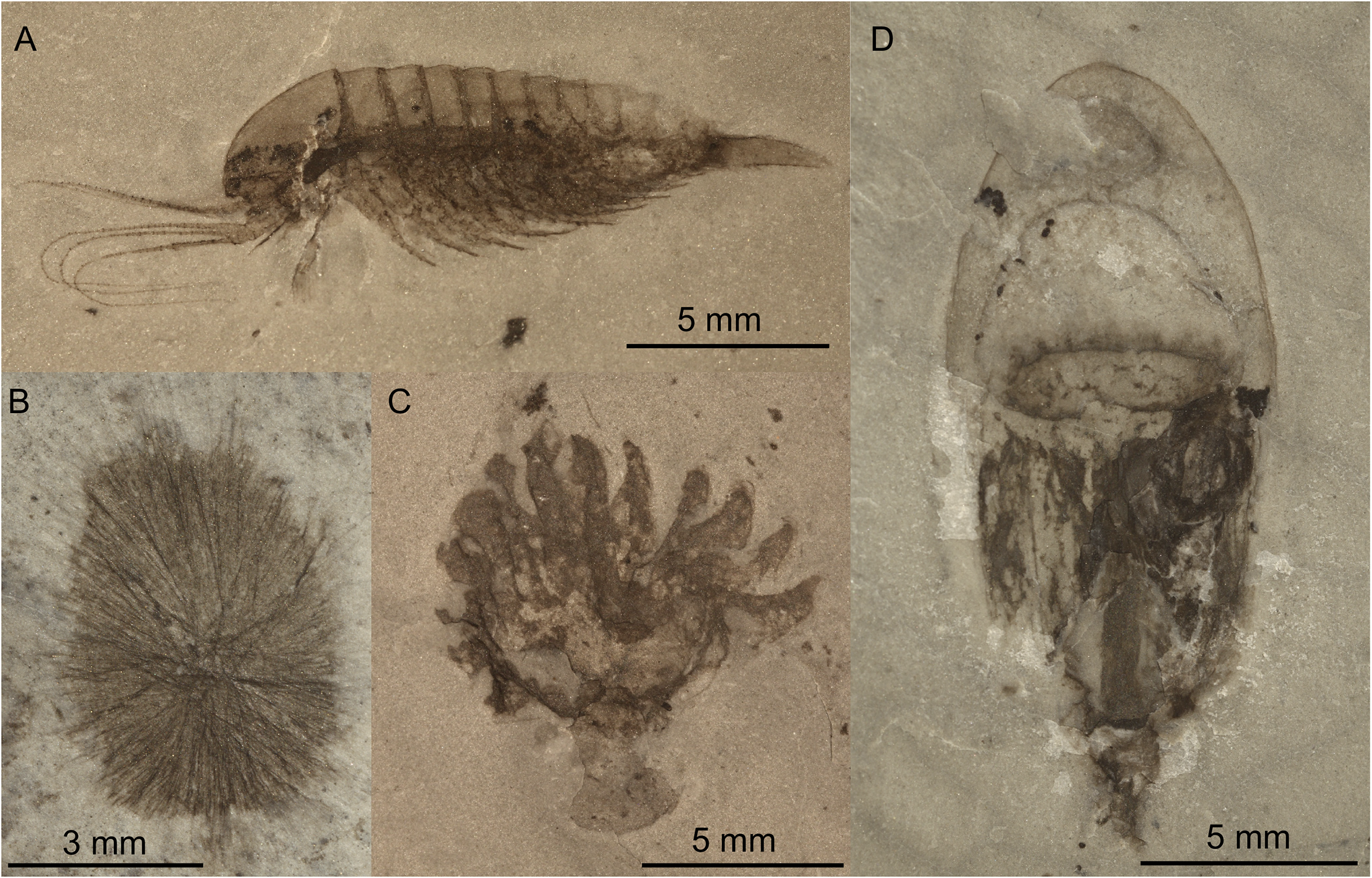

The conservation of primary organic remains as carbonaceous compression fossils in marine settings is a particularly problematic feature of the early Paleozoic fossil record. While the fossilization of the relatively recalcitrant organic remains of plants, algae, and graptolites as carbon may be explained by a combination of stagnation and obrution (e.g., Shiffbauer, et al. 2014), the carbonaceous preservation of guts, eyes, gills, and even nervous systems of soft-bodied organisms in open-marine conditions in outer shelf and shelf break settings (Fig. 3), widely known as “Burgess Shale–type” preservation (BST) is a feature unique to the Cambrian and Early Ordovician, and one that requires additional explanation (Butterfield Reference Butterfield1995, Reference Butterfield2003). While the abbreviation BST is also used to describe Burgess Shale–type fossil assemblages, here, we use BST to refer to a mode of preservation. As this mode of preservation of entire assemblages of soft-bodied organisms is restricted in time, as originally noted by Seilacher et al. (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985), and does not occur in modern environments, BST preservation is considered “anactualistic” (sensu Seilacher et al. Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985).

Figure 3. Examples of Burgess Shale–type preservation of metazoan fossils from the early Cambrian Qingjiang biota (Fu et al. Reference Fu, Tong, Dai, Liu, Yang, Zhang, Cui, Li, Yun and Wu2019), showing typical preservation as carbonaceous films (primary organic remains). A, Leanchoiliid arthropod. B, Sponge belonging to the genus Choia. C, Cnidarian sea anemone. D, Medusoid cnidarian. All images courtesy of D. J. Fu.

Burgess Shale–type preservation is widespread in outer shelf and shelf break mudstones of Cambrian–Early Ordovician age, where it occurs in more than 100 deposits at the junction of anaerobic and dysaerobic benthic environments (Gaines Reference Gaines, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017; Fu et al. Reference Fu, Tong, Dai, Liu, Yang, Zhang, Cui, Li, Yun and Wu2019). Recent reinterpretation has suggested that the Chengjiang biota occupied a delta front environment (Saleh et al. Reference Saleh, Qi, Buatois, Mángano, Paz, Vaucher, Zheng, Hou, Gabbott and Ma2022) where similar redox and biostratinomic conditions prevailed (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Droser, Orr, Garson, Hammarlund, Qi and Canfield2012b). As long understood from the type area of the Burgess Shale, BST assemblages were entrained in turbid flows; transported from habitable benthic environments to inhospitable, anoxic settings; and buried rapidly in fine-grained mud (Conway Morris Reference Conway Morris1986; Gaines and Droser Reference Gaines and Droser2010). Biostratinomic factors, namely slope angle, the presence of a shelf break, and the power of sediment-gravity flows, largely controlled the diversity of BST assemblages as well as the fidelity of preservation of fine anatomical details (Gaines Reference Gaines, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014). Although assemblages are transported, some do retain meaningful ecological information (Nanglu et al. Reference Nanglu, Caron and Gaines2020). The conservation of primary organic remains in these deposits requires either the special protection of soft-bodied fossils from the normal processes of microbial decomposition in sediments or a large-scale slowdown of microbial activity in the sediments at large (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Briggs and Yuanlong2008). Recent evidence supports both types of processes. Experimental evidence indicates that the clay mineral kaolinite, a product of intense chemical weathering, is capable of slowing microbial decay of organic tissues (Wilson and Butterfield Reference Wilson and Butterfield2014; McMahon et al. Reference McMahon, Anderson, Saupe and Briggs2016) and comprised a significant fraction of the primary clay mineralogy of BST sediments (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Tosca, Gaines, Mongiardino Koch and Briggs2018). In addition, the activity of microbial decomposition in BST sediments was shown to have been severely restricted in the early burial environment by the formation of seafloor crusts of calcite cements, which were emplaced shortly after deposition and restricted the diffusion of oxidants necessary to sustain microbial respiration into the sediments (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Hammarlund, Hou, Qi, Gabbott, Zhao, Peng and Canfield2012c). Together, these effects acted to prematurely curtail microbial activity in sediments, resulting in incomplete decay, the collapse of tissues into two dimensions, and the preservation of primary organic remains as carbonaceous compressions.

Mold and Cast- Associated with Volcanic Ash

Exceptional preservation in volcanic ash is known from outer shelf settings in the Fezouata (Ordovician) and Herefordshire (Silurian) biotas. In the Fezouata, giant radiodont arthropods ~2 m in length are preserved in silica-chlorite concretions, inferred to have been derived from the remineralization of volcanic ash at the seafloor (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Briggs, Orr and Van Roy2012a). Volcanic ash is comprised of fine metastable glass shards that are subject to rapid alteration upon entering the marine environment, liberating silica, aluminum, and iron (Duggen et al. Reference Duggen, Olgun, Croot, Hoffmann, Dietze, Delmelle and Teschner2010; Ayris and Delmelle Reference Ayris and Delmelle2012) from which quartz and clay minerals, including chlorite, may precipitate. In the case of Fezouata radiodonts, the formation of concretion-like masses of fine silicate minerals that molded the soft-bodied anatomy in three dimensions was inferred to be driven by low pH around decomposition of the giant carcasses (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Briggs, Orr and Van Roy2012a). By contrast, the Herefordshire biota includes a diversity of invertebrate forms preserved as finely detailed external molds within concretions (Fig. 2C) inside an ash bed deposited in an outer shelf setting. The Herefordshire fossil molds occur as calcite-filled voids within carbonate concretions (Orr et al. Reference Orr, Briggs, Siveter and Siveter2000; Siveter et al. Reference Siveter, Briggs, Siveter and Sutton2020). Because these concretions include a significant silicate component in addition to the carbonate matrix (Orr et al. Reference Orr, Briggs, Siveter and Siveter2000; Saleh et al. Reference Saleh, Clements, Perrier, Daley and Antcliffe2023), it is considered likely that the concretions formed within an already remineralized volcanic ash matrix that was responsible for molding the fossils. This possibility would explain both the occurrence of fossils outside the centers of concretions, where fossils usually occur, and the preservation of fossils as voids, which is unlike other examples of soft-bodied preservation in concretions (Orr et al. Reference Orr, Briggs, Siveter and Siveter2000; Siveter et al. Reference Siveter, Briggs, Siveter and Sutton2020). In this view, the Herefordshire fossils would have been preserved via a chemical process very similar to that which preserved the Fezouata radiodonts, although the giant radiodont bodies are not preserved as voids, but are also comprised of the same silica-chlorite-calcite mineral assemblage (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Briggs, Orr and Van Roy2012a). The relatively small (centimeter-scale) Herefordshire fossils were swept up into an ash-dominated sediment-gravity flow and rapidly buried, whereas the Fezouata radiodonts may have died and fallen to the seafloor onto a substrate rich in volcanic ash.

The Ediacara biota from Mistaken Point, Newfoundland, is associated with ash deposits and does not fit with typical “Ediacara-type preservation” described later for shallow-marine settings. Like other Ediacara biotas, the Mistaken Point fauna is preserved as molds and casts in sandstone; however, unlike other examples, the Mistaken Point biota occurs in a deep-marine basin, it was preserved via obrution under volcanic ash deposits, and fossils are preserved on the top surface of clastic beds, rather than on the base of obrution beds, as in the other examples described later (Fedonkin Reference Fedonkin2007). Volcanic ash is important to the biostratinomy of the Mistaken Point assemblages, but a possible role for ash in fossil diagenesis in that deposit remains unclear.

Shallow Marine

Shallow-marine settings, defined here as subtidal settings lying above storm wave base, are rarely sites of exceptional preservation, owing to generally well-oxygenated conditions, higher energy, and coarser sediment grain size relative to muddy outer shelf settings (Fig. 1D). A prominent exception to this pattern is the widespread preservation of the Ediacara biota as relatively three-dimensional molds and casts in sandstones.

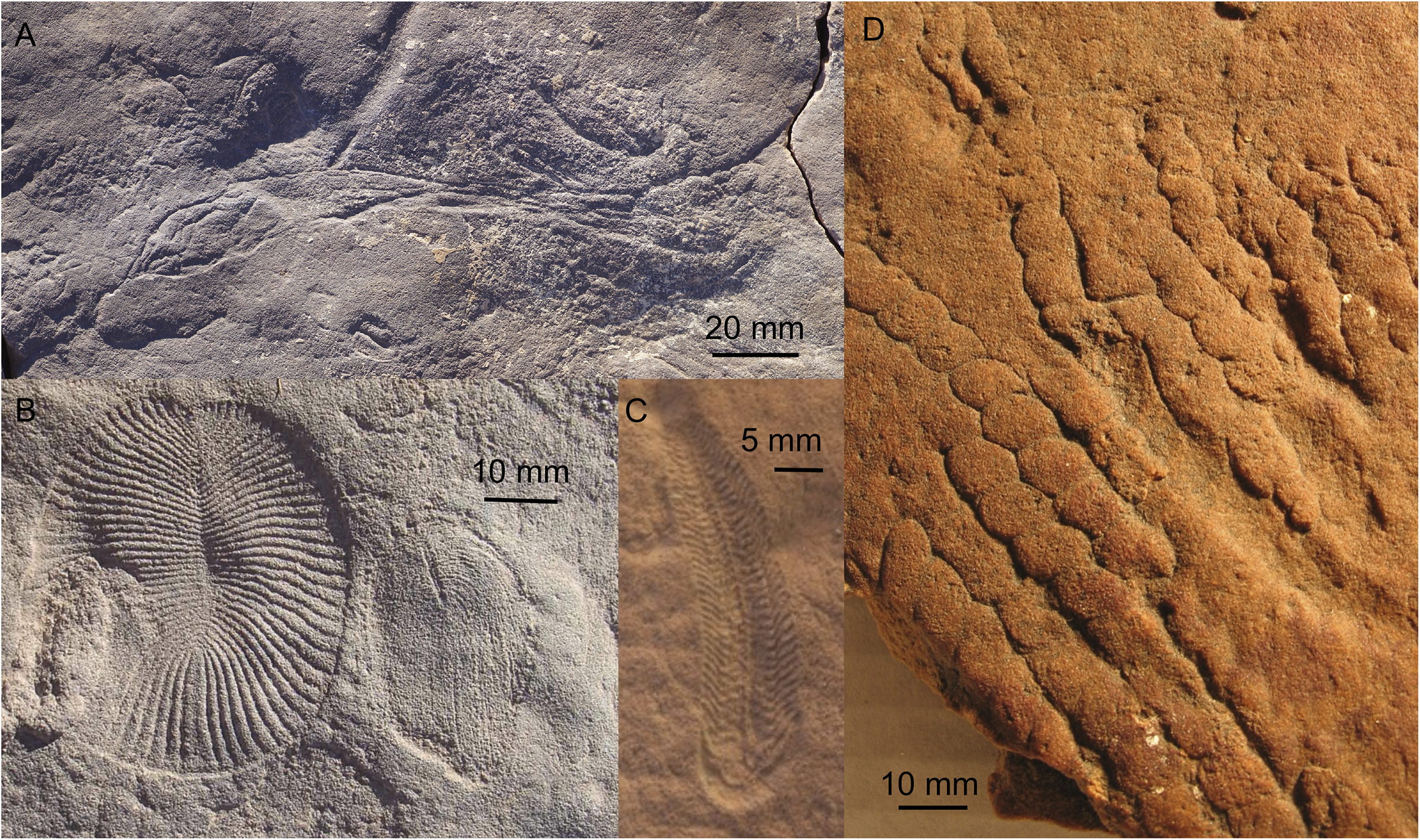

Mold and Cast: Ediacara-type Preservation

The Ediacara biota is an entirely soft-bodied suite of fossils, including the oldest known animals, that flourished worldwide during the late Neoproterozoic (Fig. 4). It is overwhelmingly known from enigmatic molds and casts in sandstone (Seilacher Reference Seilacher1999), although some examples are known from shale (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Droser, Gehling, Hughes, Wan, Chen and Yuan2013) and from carbonates (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Chen, Pang, Zhou and Yuan2021). Within sandstones, variation in taphonomic style exists; however, the dominant mode is characterized by the type localities in South Australia, where benthic communities that lived on or floated above a microbial mat were smothered under rapidly deposited sands and are preserved in hyporelief on the soles of the upper, event-deposited beds. Although fine details of external anatomy may be preserved, no internal features are captured by external molds. Like Burgess Shale–type preservation, Ediacara-type preservation (Butterfield Reference Butterfield2003) no longer occurs in normal marine settings and therefore was considered an anactualistic mode of preservation by Seilacher.

Figure 4. Fossils of the Ediacara Biota from the Ediacara Member of the Rawnsley Quartzite, Nilpena Ediacara National Park, showing typical preservation of fossils as external molds in sandstones. A, Macroscopic alga preserved in negative hyporelief with Parvancorina (bottom center). B, Dickinsonia (left) and Andiva (right) preserved in negative hyporelief. C, Spriggina preserved in negative hyporelief. D, Funisia preserved largely in positive hyporelief.

While the role of phototrophic microbial mats in typical Ediacaran ecosystems was profound (Droser et al. Reference Droser, Evans, Tarhan, Surprenant, Hughes, Hughes and Gehling2022), microbial mats alone could not have induced moldic preservation on the underside of the beds under which they were buried, and thus another mechanism is required. Pyrite veneers were hypothesized to have formed over the surfaces of fossils in the early burial environment and to have acted as a sediment-stabilizing agent that facilitated molding (Gehling Reference Gehling1999). Although dispersed pyrite grains occur in type Ediacara sediments (Liu et al. Reference Liu, McMahon, Matthews, Still and Brasier2019), they do not form continuous sheets capable of capturing molds (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling, Briggs, Gaines, Robbins and Planavsky2019). Instead, the anactualistic agent responsible for fossilization is early cementation of the sandstones by silica that precipitated from seawater before the collapse of organic remains, thereby capturing three-dimensional morphology (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016). Experimental evidence further suggests that microbial mats may act as a focus of early diagenetic cementation (Slagter et al. Reference Slagter, Hao, Planavsky, Konhauser and Tarhan2022).

Molding in Volcanic Ash

A recently discovered example of exceptional preservation in a shallow-marine setting comes from the early Cambrian Tatelt Formation, in which the complete soft-bodied anatomy of trilobites was preserved in volcanic ash, within a graded pyroclastic flow that entered a nearshore shallow-marine environment (El Albani et al. Reference El Albani, Mazurier, Edgecombe, Azizi, Elbakhouch, Berks and Bouougri2024). Rapid remineralization of the volcanic ash, as described earlier for deep-marine settings, captured the three-dimensional anatomy as hollow external molds, in a mode very similar to that of the Herefordshire biota, described earlier. The expression of these fossils is inconspicuous and provides a target for future exploration.

Delta Front

Deltas are important transitional environments characterized by the mixing of freshwater with seawater and high sedimentation rates at the locus where terrigenous sediments are introduced to the marine environment. Deltaic environments are favored to form in areas protected from wave energy (Fig. 1A). For all of these reasons, delta front environments provide ecological and taphonomic settings unlike those of other marine settings. Exceptional fossilization may occur in delta front environments through moldic preservation in siderite concretions, which may capture both terrestrial and marine biotas.

Molding in Siderite Concretions

Early diagenetic siderite forms in shallow burial environments where pore-waters are anoxic and iron oxides occur in excess of calcium and sulfate, favoring the precipitation of iron carbonate (siderite) over calcium carbonate and pyrite (Baird et al. Reference Baird, Sroka, Shabica and Kuecher1986; Vuillemin et al. Reference Vuillemin, Wirth, Kemnitz, Schleicher, Friese, Bauer and Simister2019). Although they may occur in a variety of ferruginous marine settings (e.g., Perrier and Charbonnier Reference Perrier and Charbonnier2014), siderite concretions are favored in delta front settings, which are generally dominated by mud delivered from continental environments. Clay minerals formed by oxidative weathering in soils are commonly associated with particulate iron oxides, rendering deltaic environments particularly iron-rich settings. Particulate iron oxides are readily reduced upon entering an anoxic environment, liberating iron to solution. The physical setting of delta fronts may also favor rapid burial of macrofossils, and localization of decay around carcasses in the shallow burial environment can lead to rapid depletion of oxygen from pore-waters. When optimized, this provides an ideal scenario for the growth of siderite concretions around macrofossils as loci of microbial decomposition, as best known from the Carboniferous Mazon Creek Lagerstätte (Baird et al. Reference Baird, Sroka, Shabica and Kuecher1986; Cotroneo et al. Reference Cotroneo, Schiffbauer, McCoy, Wortmann, Darroch, Peng and Laflamme2016). In that deposit, both terrestrial and marine fossils were fossilized in great detail by rapid molding in siderite (Fig. 2D), with auxiliary preservation by pyrite, calcium phosphate, and calcium carbonate mineralization, and organic preservation of some tissues, including eyes (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Dolocan, Martin, Purnell, Vinther and Gabbott2016, Reference Clements, Purnell and Gabbott2019; McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Saupe, Lamsdell, Tarhan, McMahon, Lidgard, Mayer, Whalen, Soriano and Finney2016; Bicknell et al. Reference Bicknell, Ortega-Hernández, Edgecombe, Gaines and Paterson2021).

Tidal Flat

Tidal flat environments are often subject to evaporation, leading to hypersalinity and mineral precipitation (Fig. 1D). In some circumstances, tidal flats can promote exceptional preservation via early mineralization.

Mold and Cast

Accumulations of cnidarian medusae, interpreted as shoreline strandings, occur in abundance on at least seven bedding surfaces in the late Cambrian Mt. Simon and Wonewoc Formations of Wisconsin (Hagadorn et al. Reference Hagadorn, Dott and Damrow2002; Fig. 2E), as well as in the early Cambrian of Spain and California (Mayoral et al. Reference Mayoral, Liñán, Vintaned, Muñiz and Gozalo2004; Sappenfield et al. Reference Sappenfield, Tarhan and Droser2017). These assemblages are preserved as external molds in sandstone and superficially resemble Ediacara-type preservation. While the means of soft-bodied preservation have not been investigated in petrographic or geochemical detail, it is possible that early lithification via evaporative concentration may play a role in sandstone mold and cast–type preservation in tidal flat environments.

Silica Entombment

Silica is a common evaporatively induced precipitate in carbonate-dominated tidal flat environments of the Proterozoic, where it captures microbial fossils, including those interpreted as cyanobacteria (Fig. 2F). Entombment in silica in this setting was termed “Bitter Springs–type” preservation by Butterfield (Reference Butterfield2003), who attributed the loss of this mode of fossilization in tidal flats to a secular change in the saturation state of silica in the oceans, driven first by the advent of silica biomineralizing sponges in the early Phanerozoic.

Anactualistic Fossil Preservation

Seilacher et al. (Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985) noted the issue of “anactualistic” preservation from several types of deposits within the rich record of Konservat-Lagerstätten, defining anactualistic preservation as modes of fossilization that no longer occur in comparable settings today. Three of the types of marine preservation described earlier meet this criterion: Bitter Springs–type preservation, Ediacara-type preservation, and Burgess Shale–type preservation. Each of these distinct types has a unique signature in time whereby the means of preservation is lost from the fossil record.

A meaningful counterexample is provided by preservation via entombment within volcanic ash in a marine setting (Siveter et al. Reference Siveter, Briggs, Siveter and Sutton2020; El Albani et al. Reference El Albani, Mazurier, Edgecombe, Azizi, Elbakhouch, Berks and Bouougri2024). Like other types of exceptional preservation, this mechanism is exceedingly rare in the rock record and requires precisely the right conditions, namely an ash-dominated sediment-gravity flow within the marine environment, in order to occur. These conditions, however, are not restricted in time and could occur in favorable settings today. The entire suite of volcanic-associated pathways for exceptional preservation (Fig. 1B) thus represent actualistic means of preservation, as in other fossil Lagerstätten.

Bitter Springs–type preservation, the entombment of microbes in silica in carbonate tidal flat sediments, is an anactualistic mode of fossilization. The evaporative concentration of silica in such settings is thought to have been curtailed by the onset of silica biomineralization by metazoans, which may have permanently limited silica concentrations in the oceans (Butterfield Reference Butterfield2003). Early diagenetic silica cementation in normal marine settings (i.e., non-evaporitic) of the Ediacaran, however, appears to require additional explanation.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the two other modes of preservation considered anactualistic are also the two most widespread and abundant pathways for exceptional preservation in the Ediacaran and Cambrian, respectively. It has long been recognized that exceptional fossil deposits are unusually abundant in this interval of time (Seilacher et al. Reference Seilacher, Reif and Westphal1985), a feature that is not an artifact of sedimentary rock volume (Allison and Briggs Reference Allison and Briggs1993; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017; Segessenman and Peters Reference Segessenman and Peters2022). It is furthermore clear that, although numerous modes of exceptional preservation occur within these two periods (Xiao and Knoll Reference Xiao and Knoll2000; Maas et al. Reference Maas, Braun, Dong, Donoghue, Müller, Olempska, Repetski, Siveter, Stein and Waloszek2006; Cai et al. Reference Cai, Schiffbauer, Hua and Xiao2012; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Chen, Pang, Zhou and Yuan2021); statistically, the signal of exceptional preservation in the Ediacaran is dominated by Ediacara-type preservation and that of the Cambrian is dominated by Burgess Shale–type preservation (Gaines Reference Gaines, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017).

Unlike the conditions that promote exceptional preservation in other types of fossil Lagerstätten, conditions favoring these two styles of preservation were widespread globally in the Ediacaran and Cambrian. During the Ediacaran, Ediacara-type preservation occurred in sandy, normal marine environments ranging from shallow- to deep-water settings where burial conditions were optimized, and in the Cambrian to Early Ordovician, Burgess Shale–type preservation occurred regularly in outer shelf and shelf break settings at the edge of the oxycline (Gaines Reference Gaines, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014). Both of these broad environmental settings are common in the later Phanerozoic rock record, but nevertheless, Ediacara-type and Burgess Shale–type preservation both represent “extinct” modes of fossilization in comparable marine settings. The widespread pattern of their distribution in space suggests that the anactualistic circumstances that promoted these means of fossilization were not restricted to unusual, niche environments in the late Neoproterozoic and early Phanerozoic oceans. We posit that the widespread nature of anactualistic fossil preservation in the late Neoproterozoic and early Paleozoic reflect aspects of the global marine conditions in which animals first evolved. In the following sections, we explore conditions of the Ediacaran–early Paleozoic world that played a direct role in exceptional fossilization and may have been important to the earliest metazoan ecosystems during the early evolutionary history of animals.

The Ediacaran–Cambrian World

Bioturbation

The widespread organic mats of the Ediacaran were central to the lifestyles of much of the Ediacara Biota (Droser et al. Reference Droser, Evans, Tarhan, Surprenant, Hughes, Hughes and Gehling2022). The increase in trace fossil diversity is well documented through this interval (e.g., Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Droser and Gehling2006; Mángano and Buatois Reference Mángano and Buatois2017; Darroch et al. Reference Darroch, Cribb, Buatois, Germs, Kenchington, Smith, Mocke, O’Neil, Schiffbauer and Maloney2021; Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, van de Velde, Berelson, Bottjer and Corsetti2023) but the development of the mixed layer in sediments and its impacts on ocean and sediment geochemistry and on the physical nature of sediments is more nuanced and drawn out. The advent of bioturbation and subsequent development of the mixed ground has been “blamed” for a wide range of physical and biological changes that occur over the Ediacaran and Cambrian Periods, including the decline of widespread matgrounds (Allison and Briggs Reference Allison and Briggs1993; Orr et al. Reference Orr, Benton and Briggs2003; Darroch et al. Reference Darroch, Cribb, Buatois, Germs, Kenchington, Smith, Mocke, O’Neil, Schiffbauer and Maloney2021; Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, van de Velde, Berelson, Bottjer and Corsetti2023).

The advent of active mobility is a key innovation in the evolution of animals, with the oldest widely accepted trace fossils associated with the fossils of the Ediacaran White Sea assemblage (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Droser and Gehling2006; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Diamond, Droser and Lyons2018). Helminthoidichnites, made by the bilaterian, Ikaria (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Hughes, Gehling and Droser2020) occurs at the base of the Ediacara Member of the Rawnsley Quartzite in South Australia. Ikaria was a mat grazer, leaving a furrowed trace fossil within mats on the top of the mat surface. Ikaria further followed mats under very thin discontinuous sands, leaving furrowed trace fossils preserved in negative relief on the base of thin sandstone beds. While other taxa, such as Dickinsonia, Yorgia, and Kimberella grazed the mat surface, there is no evidence of vertical bioturbation during the reign of the White Sea assemblage. Trace fossil diversity increases into and through the Nama assemblage, as exemplified in the stratigraphic sections of Namibia (Darroch et al. Reference Darroch, Cribb, Buatois, Germs, Kenchington, Smith, Mocke, O’Neil, Schiffbauer and Maloney2021). By the end of the Ediacaran, penetrative burrows in shallow-marine settings were common (e.g., Jensen and Runnegar Reference Jensen and Runnegar2005; Darroch et al. Reference Darroch, Cribb, Buatois, Germs, Kenchington, Smith, Mocke, O’Neil, Schiffbauer and Maloney2021) but did not produce a true mixed layer and did not lead to significant pore-water oxygenation in sediments (Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, van de Velde, Berelson, Bottjer and Corsetti2023). This trend continued into the early Paleozoic with only a shallow mixed layer until well into the Ordovician (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Droser, Planavsky and Johnston2015; Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, van de Velde, Berelson, Bottjer and Corsetti2023). The development of extensive grazing and, ultimately, sediment mixing, along with decreasing silica concentrations in the oceans, led to the closure of the taphonomic window for Ediacara-type preservation (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016).

While the mixed layer was not well developed, the onset of the Phanerozoic is signaled by an increase in the depth and extent of bioturbation (Droser and Bottjer Reference Droser and Bottjer1989; Mángano and Buatois Reference Mángano and Buatois2017). This trend of increasing bioturbation has been invoked as a potential cause of the closure of the early Paleozoic Burgess Shale–type “taphonomic window” (Allison and Briggs Reference Allison and Briggs1993; Orr et al. Reference Orr, Benton and Briggs2003); however, outer shelf habitats where Burgess Shale–type preservation occurs did not experience significant sediment mixing or bioirrigation during the Cambrian and Early Ordovician (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016; Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, van de Velde, Berelson, Bottjer and Corsetti2023). Furthermore, it has been documented that BST preservation, unlike Ediacara-type preservation, requires oxygen-deficient conditions (Gaines and Droser Reference Gaines and Droser2010; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Droser, Orr, Garson, Hammarlund, Qi and Canfield2012b), which exclude bioturbators and most benthos from such settings in modern environments. Indeed, the depth and extent of bioturbation are directly regulated by dissolved oxygen concentrations of bottom waters (Savrda et al. Reference Savrda, Bottjer and Gorsline1984; Savrda and Bottjer Reference Savrda and Bottjer1986, Reference Savrda and Bottjer1991). BST fossils therefore occur overwhelmingly in well-laminated, unbioturbated shale intervals inferred to have been deposited under anoxic conditions (Gaines and Droser Reference Gaines and Droser2010). Burgess Shale–type settings, however, occur near at the junction of anoxic and oxygenated bottom waters. Because the oxycline fluctuates over time, many BST deposits are characterized by interbedding of unbioturbated shale intervals, which bear exceptional fossils, with weakly bioturbated intervals that do not bear exceptional fossils (Gaines and Droser Reference Gaines and Droser2005, Reference Gaines and Droser2010; Garson et al. Reference Garson, Gaines, Droser, Liddel and Sappenfield2012). Thus, the impact of a post-Cambrian increase in the depth and extent of bioturbation may have curtailed the prevalence of this pathway for soft-bodied preservation in many outer shelf settings by eliminating the possibility for preservation in finely interbedded intervals. However, because large portions of many BST deposits were accumulated under persistently anoxic conditions, including those of the Burgess Shale, Chengjiang, and several of the most prominent BST deposits, an increase in the depth and extent of bioturbation could not have affected preservation in settings comparable to these later in time. Therefore a post-Cambrian increase in the depth and extent of bioturbation could not have been responsible for the loss of the Burgess Shale–type preservation pathway from marine settings (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Droser, Orr, Garson, Hammarlund, Qi and Canfield2012b).

Oxygen

Research over the last 50 years has profoundly reshaped our view of global redox evolution across the Ediacaran and early Paleozoic. Historically, it was assumed that molecular oxygen rose to near-modern concentrations during the Neoproterozoic/Cambrian transition, coincident with the rise of complex life (e.g., Berner et al. Reference Berner, Beerling, Dudley, Robinson and Wildman2003). Although work in recent decades unquestionably points to a major oxygenation event during the late Neoproterozoic, this work has also revealed that global atmospheric oxygen (pO2) remained at surprisingly low levels (<20% of the present atmospheric concentration) across this interval (Och and Shields-Zhou Reference Och and Shields-Zhou2012; Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Diamond, Planavsky, Reinhard and Li2021). Critically, recent work has also revealed that pO2 was unstable across the Ediacaran and Cambrian and experienced repeated pulses and crashes throughout this interval (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Lyons, Young, Kump, Knoll and Saltzman2011, Reference Gill, Dahl, Hammarlund, LeRoy, Gordon, Canfield, Anbar and Lyons2021; Li et al. Reference Li, Cheng, Zhu and Lyons2018; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao, Romaniello, Hardisty, Li, Melezhik and Pokrovsky2019; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Mills, Merdith, Lenton and Poulton2022). Low global redox conditions and redox instability profoundly shaped the marine environments of early metazoan evolution (Bowyer et al. Reference Bowyer, Wood and Poulton2017; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xiao, Romaniello, Hardisty, Li, Melezhik and Pokrovsky2019).

While the redox picture for early Phanerozoic oceans is still coming into focus, it is clear that they were characterized by widespread oxygen deficiency and instability (Saltzman et al. Reference Saltzman, Young, Kump, Gill, Lyons and Runnegar2011; Li et al. Reference Li, Cheng, Zhu and Lyons2018; Dahl et al. Reference Dahl, Siggaard-Andersen, Schovsbo, Persson, Husted, Hougård, Dickson, Kjær and Nielsen2019; Gill et al. Reference Gill, Dahl, Hammarlund, LeRoy, Gordon, Canfield, Anbar and Lyons2021; Pruss and Gill Reference Pruss and Gill2024). Redox instability in particular has also been proposed as a driver of evolutionary innovation for the earliest Phanerozoic animals (He et al. Reference He, Zhu, Mills, Wynn, Zhuravlev, Tostevin, von Strandmann, Yang, Poulton and Shields2019). As low-lying cratons were progressively flooded during the Cambrian, the connections of rapidly expanding shallow-marine settings in continental interiors to the open ocean also became restricted, amplifying local redox effects (Peters Reference Peters2007). Furthermore, the productive, nutrient-rich settings that sustained early animal communities also imposed an oxygen demand in the water column and at the seafloor, resulting in habitat fragmentation and barriers to migration of benthos (Hammarlund et al. Reference Hammarlund, Gaines, Prokopenko, Qi, Hou and Canfield2017; Guilbaud et al. Reference Guilbaud, Slater, Poulton, Harvey, Brocks, Nettersheim and Butterfield2018).

As outlined earlier, oxygen also played an essential role in providing favorable settings for exceptional preservation, particularly in the early Phanerozoic. Although the redox conditions required for Ediacara-type preservation—if any—are not yet clear (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016), widespread benthic anoxia in the early Phanerozoic was an essential prerequisite for Burgess Shale–type preservation, which was favored in outer shelf settings at the junction of anoxic and oxic water masses (Butterfield Reference Butterfield1995; Conway Morris Reference Conway Morris1986; Gaines and Droser Reference Gaines and Droser2010), and helps to explain, in part, the statistical prevalence of exceptional preservation in the early Phanerozoic (Gaines Reference Gaines, Laflamme, Schiffbauer and Darroch2014; Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017).

Tectonics

The tectonic context of the late Neoproterozoic to early Phanerozoic world is characterized by a reorganization of global tectonics in the aftermath of the protracted rifting of the long-lived supercontinent Rodinia (Li et al. Reference Li, Sv. Bogdanova, Davidson, De Waele, Ernst, Fitzsimons, Fuck, Gladkochub and Jacobs2008). Indeed, much of the Ediacaran sedimentary rock record reflects deposition in rift basins along continental margins (Segessenman and Peters Reference Segessenman and Peters2022). As widely recognized, most continental cratons were surrounded by passive margins and became clustered around the equator (e.g., Hoffmann and Schrag Reference Hoffman and Schrag2002). A major transition in global tectonics occurred during the Ediacaran, when several cratons collided in the Pan-African orogeny to form the supercontinent Gondwana, while other cratons remained tectonically quiescent, including Baltica, Laurentia, and Siberia (Rino et al. Reference Rino, Kon, Sato, Maruyama, Santosh and Zhao2008).

While the Ediacara Biota flourished in shallow-marine rift-basin and rifted-margin settings, the Cambrian is characterized by widespread flooding of low-lying cratonic interiors and the rapid expansion of shallow-marine habitats (Peters and Gaines Reference Peters and Gaines2012; Peters and Husson Reference Peters and Husson2017). This rapid expansion of shelf area has been linked to the Cambrian explosion of animal diversity (Dalziel Reference Dalziel2014). During middle early Cambrian time (stage 3), the Pan-African orogen began to undergo gravitational collapse, leading to another large-scale plate tectonic reconfiguration around some margins of the supercontinent, where subduction was initiated or enhanced, resulting in uplift and loss of continental margin shelf area (Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Goodge, Brock, Betts, Park, Hughes and Gaines2024).

Environments in which Burgess Shale–type deposits of early Paleozoic age formed were established following flooding and the development of outer shelf conditions on the continents, where the chemocline intersected the seafloor. The flooding of broad, rapidly subsiding continental margins was key to the widespread development of such conditions across passive margins.

Climate

The base of the Ediacaran period is marked by the abrupt termination of “Snowball Earth” conditions and the transition to a greenhouse world (Hoffman and Schrag Reference Hoffman and Schrag2002). Greenhouse conditions subsided by the mid-Ediacaran Gaskiers glaciation, which was rapidly followed by the first fossil records of the Ediacara Biota, on the Avalon Peninsula (Pu et al. Reference Pu, Bowring, Ramezani, Myrow, Raub, Landing, Mills, Hodgin and Macdonald2016). Additional geologic evidence from the cold-water carbonate mineral glendonite points to mid-Ediacaran cooling (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Suess, Chen, Ma, Wang and Xiao2020).

Geologic evidence and carbon cycle models indicate a return to hothouse conditions by the early Cambrian, with pCO2 likely in the range of 16–32X PAL (preindustrial atmospheric level) (Berner Reference Berner2006; Wong Hearing et al. Reference Wong Hearing, Harvey, Williams, Leng, Lamb, Wilby, Gabbott, Pohl and Donnadieu2018, Reference Wong Hearing, Pohl, Williams, Donnadieu, Harvey, Scotese, Sepulchre, Franc and Vandenbroucke2021). Greenhouse conditions that were maintained across the Cambrian were sustained by volcanic outgassing (McKenzie et al. Reference McKenzie, Hughes, Gill and Myrow2014). Detrital zircon abundance, assessed through compilation, suggests a Phanerozoic high in arc volcanism during the Cambrian (McKenzie et al. Reference McKenzie, Horton, Loomis, Stockli, Planavsky and Lee2016) that matches well with geologic observations of elevated pCO2 and greenhouse climate (Wong Hearing et al. Reference Wong Hearing, Pohl, Williams, Donnadieu, Harvey, Scotese, Sepulchre, Franc and Vandenbroucke2021).

Records of continental weathering confirm that the Cambrian greenhouse was accompanied by extensive continental weathering, which in the absence of land plants was driven by elevated pCO2 (Driese et al. Reference Driese, Medaris, Ren, Runkel and Langford2007; Medaris et al. Reference Medaris, Driese, Stinchcomb, Fournelle, Lee, Xu, DiPietro, Gopon and Stewart2018; Colwyn et al. Reference Colwyn, Sheldon, Maynard, Gaines, Hofman, Wang, Gueguen, Asael, Rienhard and Planavasky2019; Wong Hearing et al. Reference Wong Hearing, Pohl, Williams, Donnadieu, Harvey, Scotese, Sepulchre, Franc and Vandenbroucke2021). Lithium isotope evidence from shales suggests that the early Cambrian in particular was a time of intense weathering and clay formation (Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zhao, Sperling, Gaines, Kalderon-Asael, Shen and Li2024). High surface temperatures may also have led to sluggish oceanic circulation and overturn, particularly in epicratoinc seas, where many episodes of the Cambrian are associated with the development of anoxic conditions (Peters Reference Peters2007; Gill et al. Reference Gill, Lyons, Young, Kump, Knoll and Saltzman2011; Zhuravlev et al. Reference Zhuravlev, Wood and Bowyer2023).

Widespread Exceptional Preservation and the Ediacaran–Cambrian World

Both Ediacara-type and Burgess Shale–type preservation are a consequence of the physical, biological, and chemical world during the rise of animal life. Both styles of preservation have been linked to early cementation of sediments. In the Ediacaran, early lithification by seawater-derived silica cements captured soft-bodied biotas as molds in sandstone (Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016), whereas in Burgess Shale–type preservation, seawater-derived calcite cements formed crusts over the seafloor following obrution events, restricting exchange of pore-waters with oxidant-bearing seawater, thereby curtailing microbial activity and resulting in the conservation of organic remains of soft-bodied fossils (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Hammarlund, Hou, Qi, Gabbott, Zhao, Peng and Canfield2012c). In addition, there is evidence that an abundance of the clay mineral kaolinite in Burgess Shale–type settings played a role in helping to stabilize organic remains against decomposition (Wilson and Butterfield Reference Wilson and Butterfield2014; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Tosca, Gaines, Mongiardino Koch and Briggs2018).

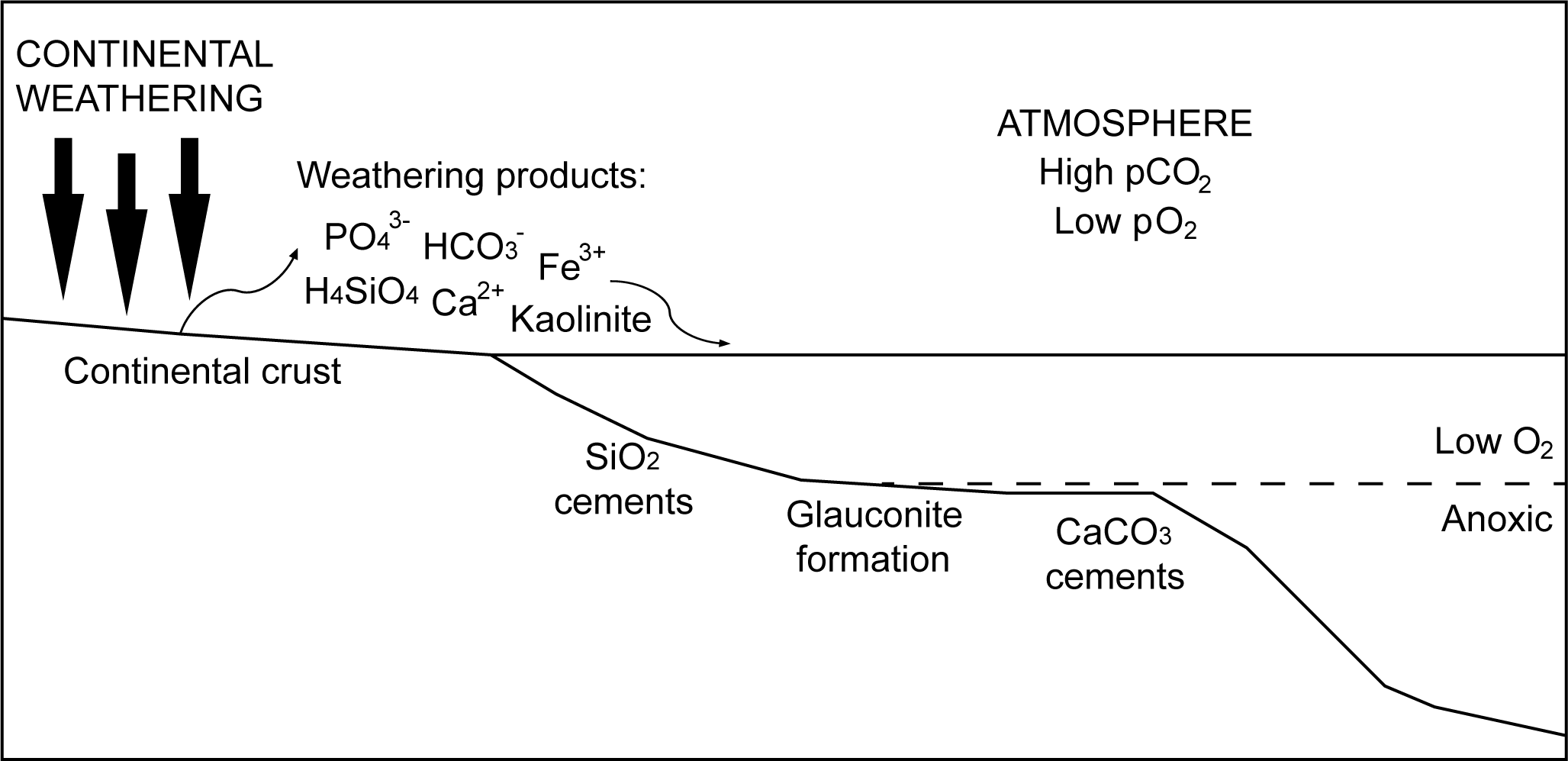

The features that promoted these types of exceptional preservation, the prevalence of dissolved silica and carbonate and the abundance of the clay mineral kaolinite in the oceans, all share a common origin (Fig. 5). Kaolinite is produced by intense chemical weathering of continental crust, which releases silicic acid, calcium, and bicarbonate to the oceans. Earth system conditions in the late Neoproterozoic and Cambrian appear to have been primed to promote the delivery of all three of these weathering products to the oceans. Chemical weathering is limited by exposure of basement rock. The Ediacaran–Cambrian interval is characterized by extensive exposure of igneous and metamorphic basement rock that is unique in at least the last 900 Myr of Earth history (Peters and Gaines Reference Peters and Gaines2012). All available evidence indicates an intense greenhouse climate followed the Snowball Earth epoch of the Cryogenian and, following the Gaskiers glaciation in the mid-Ediacaran, was maintained across the Cambrian Period (Wong Hearing et al. Reference Wong Hearing, Harvey, Williams, Leng, Lamb, Wilby, Gabbott, Pohl and Donnadieu2018, Reference Wong Hearing, Pohl, Williams, Donnadieu, Harvey, Scotese, Sepulchre, Franc and Vandenbroucke2021; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zhao, Sperling, Gaines, Kalderon-Asael, Shen and Li2024). Atmospheric losses of CO2 to continental weathering were offset by extensive volcanic outgassing around the margins of Gondwana associated with the pan-African orogeny (Tasistro-Hart and Macdonald Reference Tasistro-Hart and Macdonald2023). Macrostratigraphic facies data and geochemical proxies also support intensive chemical weathering during this time (Peters and Gaines Reference Peters and Gaines2012).

Figure 5. Cartoon diagram illustrating factors important to widespread exceptional fossil preservation in the Ediacaran and Cambrian Periods. Intense chemical weathering of igneous and metamorphic basement rock under a high pCO2 atmosphere resulted in an elevated flux of weathering products via rivers to the oceans. Key weathering products include the nutrients Fe3+ and PO43−, silicic acid (H4SiO4), calcium (Ca2+), and bicarbonate (HCO3−), from which silica and calcium carbonate cements precipitated, and the clay mineral kaolinite. Low atmospheric pO2 and greenhouse climates resulted in widespread oxygen-deficient conditions on marine shelves.

In addition to promoting the early lithification of sediments in the Ediacaran and Cambrian, an ocean rich in products of chemical weathering of the continental crust, in both dissolved and clastic form, may have held additional significance for early animals and their ecosystems. An influx of dissolved minerals to the oceans has been linked to the advent of biomineralization (Peters and Gaines Reference Peters and Gaines2012; Wood Reference Wood2018). Chemical weathering also liberates iron and phosphorous, two of the three major nutrients limiting to primary productivity, from silicate minerals. During weathering, iron and phosphorous are retained in soils, often adhering to the charged surfaces of clay minerals, including kaolinite. The delivery of kaolinite to the oceans in significant quantities was thus accompanied by the delivery of nutrients, stimulating the primary productivity that sustained early metazoan ecosystems (Hammarlund et al. Reference Hammarlund, Gaines, Prokopenko, Qi, Hou and Canfield2017). The abundance of glauconite in Cambrian marine sediments also resulted directly from the delivery of kaolinite and iron (Peters and Gaines Reference Peters and Gaines2012). Low-oxygen conditions of the late Neoproterozoic–Cambrian, which played a significant role in the distribution of exceptional preservation across this interval (Muscente et al. Reference Muscente, Schiffbauer, Broce, Laflamme, O’Donnell, Boag, Meyer, Hawkins, Huntley and McNamara2017), also would have impacted early metazoan ecosystems (Hammarlund et al. Reference Hammarlund, Gaines, Prokopenko, Qi, Hou and Canfield2017; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Diamond, Droser and Lyons2018, Reference Evans, Tu, Rizzo, Surprenant, Boan, McCandless, Marshall, Xiao and Droser2022).

It is meaningful that, after their decline in open-marine settings, both type Ediacara-like preservation as molds and casts in sandstones and type Burgess Shale–like carbonaceous compression fossils occur in other types of environments that favor early lithification. Mold and cast preservation on tidal flats (Hagadorn et al. Reference Hagadorn, Dott and Damrow2002; Mayoral et al. Reference Mayoral, Liñán, Vintaned, Muñiz and Gozalo2004; Sappenfield et al. Reference Sappenfield, Tarhan and Droser2017) may have resulted from early cementation of shoreline sands under evaporative conditions. Carbonaceous preservation of soft-bodied animals in the post-Cambrian occurs most prominently in alkaline stratified lake systems (Fig. 1A) prone to inorganic cementation. Both examples are informative, as they point to the unique nature of ocean chemistry during the late Neoproterozoic to early Phanerozoic. Study of fossil Lagerstätten has helped to reveal that animals evolved and first proliferated in oceanic environments prone to early cementation, high productivity, shelf oxygen deficiency, and habitat fragmentation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Clements, J. Schiffbauer, an anonymous reviewer, and editor M. Patzkowsky, who provided thoughtful and substantive comments that strengthened the article considerably. We thank W. Weyland for drafting artwork in Figure 1 and R. Bicknell, D. Briggs, P. Cohen, D. Fu, J. Hagadorn, J. Utrup, and D. Fu for photographs used in Figures 2 and 3. R.R.G. acknowledges support from Pomona College and from NSF EAR-1554897.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.