Curtice (Reference Curtice2021, this issue) helpfully brings out learning points from the Court of Protection judgment in AMDC v AG & Anor [2020] on mental capacity assessments, with emphasis on ‘the vital importance of clearly showing the working out and explanation of any opinions and conclusions arrived at in expert reports [on mental capacity]’.

We start by drawing back from the details of this case and from the Court of Protection rules to highlight the broader significance of what has been happening in England and Wales since the UK parliament enacted the Mental Capacity Act in 2005. The Act consolidated decades of case law on consent and capacity into a single codified piece of statute. It was largely the brainchild of Baroness Hale of Richmond (former President of the UK Supreme Court) during her period at the Law Commission in the 1990s. It received 10 years of pre-legislative scrutiny and considerable parliamentary debate. Noteworthy at the time were debates about assisted dying ‘via the backdoor’ with refusals of life-sustaining medical treatment (debates that remain until this day). Since its enactment debates have arisen about the interface with the Mental Health Act 1983 (debates still unresolved). What is remarkable, however, was the creation of a clear legal framework for detailed examination of mental capacity and best interests and the formation of a new specialist and superior court of record (the Court of Protection) to oversee the operation of the framework. Such prominence given to issues of consent and capacity in highly vulnerable populations was rather unprecedented internationally. Some other jurisdictions (as diverse as Singapore and Northern Ireland) have adopted the Mental Capacity Act pretty much wholesale.

As Curtice points out, and as Justice Poole identified in AMDC, the Court of Protection is not an adversarial court. It seeks justice through an active, inquisitorial court process rather than by refereeing between the claims advanced by competing parties and it typically relies on the medical/psychiatric/social evidence given to it by jointly instructed experts. It seeks such evidence because it is dealing, by definition, with people for whom questions have arisen about decision-making under conditions of impairment of mind or brain. We thus have a court in which fundamental legal principles of choice and decision are meeting fundamental concepts in psychiatry.

It has been over 10 years now since the Court of Protection commenced its work. In this complex area, there can be different views. There are several published cases in which experts have disagreed with each other on capacity questions and a small number of further cases where the capacity determinations of judges have opposed the conclusions of experts (Ruck Keene et al Reference Ruck Keene, Kane and Kim2019). However, a key learning point has been that a large body of published cases has been produced which reflect a sizable body of experience (possibly the largest available anywhere) of interactions between judges and expert witnesses struggling to articulate ‘clear explanations’ for whether a person does or does not have capacity to make a decision about a matter of significance. Next we summarise our conclusions from researching this evidence.

‘Clear explanation’ for capacity

Curtice cites Justice Poole in AMDC v AG & Anor [2020] as saying ‘an expert report on capacity is not a clinical assessment’. Quite so, insofar as such an expert report is produced for purposes of considering the person's decision-making capacity, rather than for a clinician determining what, clinically, is the right course of action. But an expert report should not be an ‘un’-clinical assessment. Indeed, the distinctive quality of the mental capacity assessment is that it blends knowledge of law with knowledge of psychopathology. It asks: is this person able to decide this matter for themselves? And if not able, why? The why must relate to knowledge of psychopathology (or what the Mental Capacity Act calls ‘impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’).

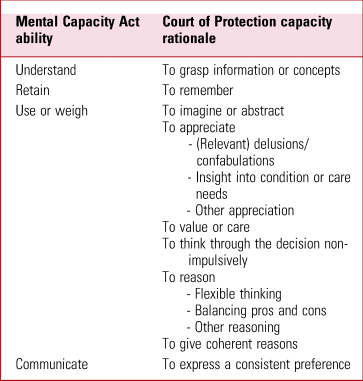

Kane et al (Reference Kane, Keene and Owen2021) undertook a detailed content analysis of all published cases in the Court of Protection to derive a typology of explanations (or ‘rationales’) for capacity or incapacity. These rationales go beyond the black letters of the Mental Capacity Act and are grounded in both the clinical experience of the experts and the judicial checks and balances of the Court. The rationales (Table 1) are couched in broadly descriptive psychological terms, but they relate to mental capacity assessment rather than to clinical assessment. In particular, the rationales give greater refinement to the broad Mental Capacity Act category of ‘inability to use or weigh relevant information in the process of making a decision’ (our italics) and afford the potential for greater transparency and reliability in what can otherwise be a rather messy process of matching clinical phenomena to the letters of the statute (Kim Reference Kim, Kane and Ruck Keene2021). They provide a potential framework for clinicians to show the ‘working out’ and explain their conclusions on capacity (for specific decisions).

TABLE 1 Explanations (‘rationales’) for capacity or incapacity in relation to the Mental Capacity Act capacity assessment

Source: after Kane et al (Reference Kane, Keene and Owen2021).

Justice Poole in AMDC reminds us of the decision specificity of the capacity assessment and the importance of both relevant information and practicable steps taken to help a person make a decision for themselves. Relevant information (and information about relevant options) is a crucial component of capacity assessment that requires clinicians to take stock and, when the decision is not clinical or is outwith their area of expertise, seek input from others (such as the instructing lawyers in court cases). The courts are acquiring experience on what is relevant information for different areas of decision-making and useful resources are being assembled (summarised in 39 Essex Chambers 2021). On practicable steps we advise clinicians, when time allows, to not rush into capacity determinations and to document what they have done to help a person decide: both to ensure good faith compliance with the Mental Capacity Act and to stimulate reflection on what might actually help and could be tried.

Private versus NHS reports

Mirza & Kripalani (Reference Mirza and Kripalani2019) have raised the interesting question of resources in private versus National Health Service (NHS) reports in service of the Court of Protection. That there are time and cost implications of providing these reports is clear and implications for a publicly funded health service, with its competing resource demands, are extremely important to debate. The Court of Protection has sought to recognise these implications in a Practice Direction about these so-called ‘section 49 reports’ (www.judiciary.uk/publications/14e-section-49-reports/). What is not acceptable, in our view, is for NHS trusts to have inadequate legal support to help NHS clinicians prepare reports when a case needs to go to the Court of Protection or to help senior NHS clinicians make reasonable decisions about how far a multidisciplinary team can be expected to deal with a capacity or best interests case that is finally balanced or, despite good efforts, is not proving possible to get consensus on. Sadly, there are NHS trusts in which this legal support for Mental Capacity Act integration is just not good enough relative to what is at stake for patients, their carers and for clinicians.

Guidance

We agree that the legal guidance from Justice Poole in AMDC v AG & Anor [2020] is helpful. In the Mental Health and Justice project (mhj.org.uk) we are seeking to take guidance further. Research shows that teaching clinicians legal rules on mental capacity is possible but that they tend to not implement them once learned (Spencer Reference Spencer, Wilson and Okon-Rocha2017). Guidance that is more clinically grounded, multiperspective and borne out by hard cases we think is more likely to be internalised and implemented. Guidance aiming to meet these criteria will be freely available in 2022 at capacityguide.org.uk and it will evolve as mental capacity policy and practice evolves too.

Author contributions

G.O. drafted the commentary and N.K. and A.R.K. made written contributions. All authors agreed the final content.

Funding

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.