A Review of the Past Findings and Current Major Research Issues

The South Korean Twin Registry (SKTR) is an ongoing nation-wide volunteer registry of South Korean twins and their families. The general goal of the SKTR is to understand genetic and environmental etiologies of psychological and physical traits among South Koreans. Since its inception (Hur, Reference Hur2002; Hur et al., Reference Hur, Shin, Jeong and Han2006), twin studies based on the SKTR samples have demonstrated that genetics play a significant role in individual differences in many physical and psychological traits among South Koreans, especially from childhood to young adulthood (Table 1). For physical traits, body mass index (BMI), and cold hands symptoms in adolescence and young adulthood showed very high heritability (about 60–90%) with little shared environmental influences (Hur, Reference Hur2007a; Hur et al., Reference Hur, Kaprio, Iacono, Boomsma, McGue, Silventoinen and Mitchell2008, Reference Hur, Chae, Chung, Kim, Jeong, Kim and Kim2012) although during childhood these traits were significantly influenced by shared environmental factors (Hur & Shin, Reference Hur and Shin2008). Substantial intrauterine environmental influence was also observed in birth weight (Hur et al., Reference Hur, Luciano, Martin, Boomsma, Iacono, McGue and Han2005). Genetic influences on childhood temperament and adolescent personality traits fell between 30% and 60%, of which non-additive genetic effects were important (Hur, Reference Hur2006, Reference Hur2007b, Reference Hur2009a; Hur & Rushton, Reference Hur and Rushton2007; Hur et al., Reference Hur, Jeong, Schermer and Rushton2011). For personality traits, shared environmental influences were generally negligible during childhood and adolescence as well as in young adulthood. Environmental factors important for personality and temperament were primarily those resulted from individual-specific experiences (Hur, Reference Hur2006, Reference Hur2007b, Reference Hur2009a; Hur & Rushton, Reference Hur and Rushton2007; Hur et al., Reference Hur, Jeong, Schermer and Rushton2011). The estimates of genetic influences on many psychiatric symptoms were similar to those found in personality traits (Hur, Reference Hur2008, Reference Hur2009b; Hur & Jeong, Reference Hur and Jeong2008; Hur et al., Reference Hur, Cherney and Sham2012). However, shared environmental influences were notable in conduct problems (Ha et al., Reference Ha, Jin, Koo, Jo, Kim, Kim and Hur2010), depressive symptoms in males (Hur, Reference Hur2008), and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in females (Hur & Jeong, Reference Hur and Jeong2008). As with personality traits, many psychiatric symptoms demonstrated that individual-specific environmental influences were important sources of variation. Overall, these findings based on the SKTR samples were consistent with the results from Western twin samples, suggesting that the proportions of genetic and environmental influences on psychological and physical traits found in Western countries may be generalized to South Koreans.

TABLE 1 Genetic and Environmental Influences (%) on Various Traits Estimated From Sub-Samples of the South Korean Twin Registrya

A = additive genetic effects; C = shared environmental effects; D = non-additive genetic effects; E = individual environmental effects including measurement error. 95% CI are in parenthesis.

aMain effects of age were adjusted; main effects of sex were also adjusted when males and females were not separated.

bAverage across seven scales (Extraversion, Neuroticism, Psychoticism, Impulsivity, Venturesomeness, Empathy, and Lie).

cAverage across Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability scales.

Our current major research focus of the SKTR samples includes detection of G × E interactions for the mean level as well as for the variations of psychological and physical phenotypes. To examine the process of G × E interactions, we make efforts to identify specific genetic, and environmental protective and risk factors for psychological and physical traits. We also investigate developmental differences in genetic and environmental influences on phenotypes and endophenotypes, using age as a continuous moderator. The large age span of twin participants in the SKTR enables us to pursue this research question. In line with these research interests, we recently extended the SKTR sampling in two important ways. First, as explained below, we began to recruit twins from lower socio-economic families, which will facilitate studies of interactions between genetics and social classes. Second, as a parallel twin study of the SKTR, we started to develop an age-matched sample of Nigerian twins and siblings (Hur et al., Reference Hur, Kim, Chung, Shin, Jeong and Auta2013 in this issue). The combined data sets of Nigerian and South Korean twins will provide a unique opportunity to investigate population group differences/similarities in psychological traits between South Korean and Nigerian children and adolescents.

Registry Membership

Twins in the SKTR have been recruited from a variety of sources, including large maternity hospitals, twin mothers’ clubs, media advertisement, and kindergartens and schools throughout South Korea (Hur et al., Reference Hur, Shin, Jeong and Han2006). More recently, to reach twins from lower socio-economic families who are typically under-represented in volunteer research projects, we began to call and send letters to the community child centers and youth counseling centers supported by the government in all provinces in South Korea. As these centers support children and adolescents from poor families and those with problem behaviors, a successful recruitment of these children and adolescents is likely to make the participants of the SKTR well representative of a large number of low-income as well as middle- to upper-class families in South Korea.

Due to a high mobility rate among residents in large cities in South Korea, however, we have lost the contact information of twins for the past years. To replenish the registry membership, we continue to recruit new volunteers as well as to trace contact information of the twins who moved. Table 2 presents the number of individual twins who have been at least once registered with the SKTR.

TABLE 2 Numbera of Twins Who Have Been Registered With the SKTR By Age Group and the Sex-Ratio of Each Age Group

aIndividual twins.

Zygosity Assignment

Opposite-sex twins in the SKTR are automatically assigned to dizygotic twins. Zygosity assignment for the same-sex twins is initially based on the questionnaire method and in some cases by chorionicity determined by the examination of placentas in the pathology lab after delivery. However, the questionnaire method is currently supplemented with analysis of 16 micro-satellite DNA markers.

Measures

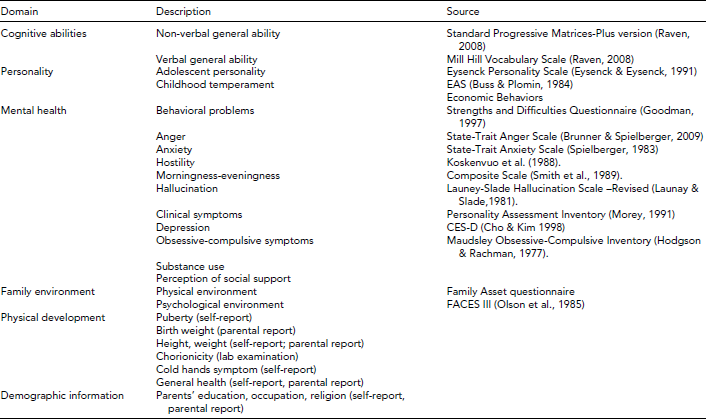

Studies using the SKTR samples encompass a broad range of psychological and physical domains. The measures for the SKTR samples have been chosen for their high psychometric properties and for their broad acceptance in the field. These practices allow cross-national comparison studies. Table 3 provides an overview of selected measures used in the SKTR.

TABLE 3 Description of Selected Measures Used in the South Korean Twin Registry

Conclusions and Future Plans

This article is not an exhaustive description of all the studies of the SKTR. Development of the SKTR is an ongoing process. Plans are still underway to conduct extensive genotyping in order to examine polymorphisms associated with psychological and physical traits among South Koreans. Efforts are also being made for epigenetic analyses and co-twin-control studies using a subset of the SKTR sample.

Acknowledgments

The SKTR has been supported by the National Research Foundation grants in Korea and Pioneer Fund, USA. The authors would like to thank the twins and their families and many research assistants who participated in the SKTR.