Tricontinentalism expressed a rebel movement within the international system. The rebellion of the South against the North predated the time in which the specter of Marxism or communism spread over the face of the earth. It opposed the structure of North-South domination established with the conquest and colonization of people in Latin America, Asia, and Africa by European powers in the Global North from the sixteenth century onwards. Beginning with the scramble for Africa and continuing through the early twentieth century, European imperialism increasingly took a more modern form, finding increasingly efficient ways to exploit and export natural resources and the fruits of colonial labor. Anticipated by the United States from the time of the Spanish-American War (1898),Footnote 1 this new style of imperialism did not require direct political and military domination of the colonial regimes and its associated costs, but instead control of the colonial economies through trade, financial, and technological dependence, and pacts with local establishments. As the colonial countries gained independence through uneven and disconnected political and military struggles in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the new sovereign states confronted a world order where uneven economic structures and conditions continued to favor the interests of Euro-American states – what was called then and since neocolonialism.Footnote 2

It was between these first independent states of the colonial world in Asia and Africa – Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Republic (UAR), and Ghana – where the first attempts to build alliances developed, even beyond their own regions. From the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung held in Indonesia in 1955 through the constitution of the Movement of Non-Aligned Countries established in 1961, the notion of an international forum responsive to the interests of the Global South emerged around five key principles: mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; nonaggression; noninterference in internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence.Footnote 3

In the 1960s, the evolution of this movement would produce a grand strategy aimed at uniting states that had emerged from anti-colonial and national liberation struggles, revolutionary movements, and progressive forces throughout the world. They would oppose the hegemony of the United States and its allies, the exclusionary logic of a bipolar world, and the sectarianism and disagreements that divided the major socialist powers: the Soviet Union and China. This strategy sought to claim the right for states in the Third World to define their own paths of national liberation – the construction of socially just societies and sovereignty – on the edges of these spheres of influence. Broadly defined, this movement sought to create a new space of dialogue as an alternative to the bipolar international system that emerged during the Cold War.

Popular memory of the era has reduced it to a time of idealism and frustrated struggles, utopias and voluntarist projects, insurgent movements and guerrilla war, all overcome by the pragmatic demands of realpolitik.Footnote 4 Scholarly history has enshrined many of these attitudes, reproducing ideological stereotypes and political simplifications first generated during the Cold War, which still permeate popular understandings and academic assessments of the period.Footnote 5 By this logic, nothing of that period has anything to do with the challenges and problems of today’s world, much less with plausible responses to and collaborative ways of confronting them. To reach a more accurate understanding of Tricontinentalism and the broader Third World project, scholars need to more critically explore the specific global and regional contexts in which this movement took place, review the main strategic conceptions of Tricontinentalism, appreciate its vision of alliance politics, and evaluate them within the context in which they evolved.

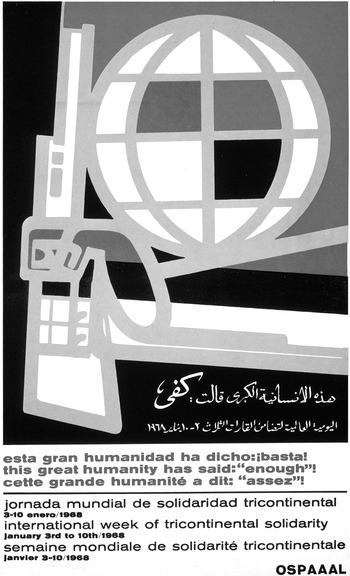

Tricontinentalism is sometimes perceived as a Marxist-like set of ideological principles and armed liberation agendas. Our essay argues for its multiplicity of aims and strategies. Building on the insights provided by declassified primary material from the OSPAAAL archives in Cuba, this investigation will explore some of the complexities that characterize the Tricontinental movement and the huge task of creating a Third World alliance, independent from Soviet and Chinese hegemonic influences. It will explain some interests and motivations behind these power factors and ideological contradictions, and the role played by Cuba in moderating them, from its leading position in the Tricontinental movement and Havana conference (1966). And, making use of sources from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), it will explore a particular and not-yet-investigated set of interactions between the Third World and Second World nations other than the Soviet Union. These negotiations between Germans and Cuba around the Tricontinental also demonstrate the complexity of the Tricontinental movement, a movement that was anything but just responding to the Soviet versus US alignment and singular in its tactics.

Cold War, Non-Aligned, and Revolutionary Logic

After World War II, the Cold War divided the planet into geopolitical poles. Gdansk, Budapest, and Rostock were under the Warsaw Pact bloc, while Marseille and Turin – where the two largest Communist parties outside the USSR held sway – fell within the borders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the anti-communist bloc. The new left variously emerging around the globe worked to separate itself from this old guard: from the communist heirs of the Comintern attached to Moscow’s line; from betting all on electoral-parliamentary systems; and from the order that emerged from the Yalta Conference, which divided the world between the Soviet East and capitalist West.

On the crest of this new heterodox wave, the left wings of almost all the established parties, from the Communists to the Christian Democrats, broke off; a proliferation of new movements of radical inspiration emerged; Marxist thought came into fashion, even in the great universities of the West; new publishers dedicated to its provisioning appeared, disseminating works from Lenin and Trotsky to José Carlos Mariátegui and Che Guevara, Mao Zedong and Amílcar Cabral, Antonio Gramsci and György Lukacs, Frantz Fanon and Mehdi Ben Barka.Footnote 6

In that context, the political challenge posed by the Cuban revolution toward the hegemonic power of the United States can be measured by what Americans call the Cuban Missile Crisis, but which is better known in Cuba as the October Crisis (La Crisis de Octubre). The manner in which the superpowers reached a compromise, a verbal agreement between Kennedy and Khrushchev, without any formal treaty that considered Cuba’s national security, avoided nuclear war, but left Cuba exposed to a simple US pledge not to invade the island. After the Crisis of October in 1962, Soviet aid remained vital, but the military umbrella provided by the alliance appeared to have weakened. So close to the United States, so far from the European and Asian East, Cuba felt isolated and far from secure. The only socialist state that truly shared its vision of active revolution was the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, a comparable country on the periphery of the bipolar order, which would attract almost all the destructive capacity of the American Empire, and would, unintentionally, become a lightning rod for the island.Footnote 7

It is for this reason that Che Guevara’s 1967 urging to “create two, three, many Vietnams”Footnote 8 was not a mere war cry in the ears of Cubans, but a strategic requirement for the common cause of the national liberation revolutions on three continents.Footnote 9 With the Soviet Union seeking accommodation with the First World (see Friedman, Chapter 7), it was vital for Asian, African, and Latin American states to collectively confront the power of the United States since no one had the power to do so alone. This message had an impact beyond the Global South. Actors around the globe interpreted Guevara’s message both in solidarity and according to their particular circumstances; we discuss the example of West German activists later.

The undeclared, 55-plus year war that the United States continues to wage upon the Revolution isolated the young Cuba within the hemisphere and left it with few opportunities for dialogue. From early on, the ideological and political struggle, often silent but very evident, between the island and the two largest socialist powers separated Cuba, China, and the Soviet Union on the paths of the Revolution and in the building of the new society. Between 1964 and 1970 that geopolitical isolation became critical.Footnote 10 From this situation of regional diplomatic isolation, marginalization in the socialist camp, and imminent danger, the heretic Havana found its partners almost exclusively in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia, especially among the revolutionaries.Footnote 11

The Tricontinental: An Inside Look

Tricontinentalism expressed not only the rebellion of the South against the North but also a confrontation of various and sometimes competing interests within the South. The coincidence of processes of colonial independence with the revolutions in Russia in 1917 and China in 1949, along with the emergence of these states as defiant actors in a world order dominated by the Western powers, led to a new form of dependency within the movement of Southern countries. In search of support, the newly independent states gravitated increasingly toward the international sphere created by the Soviet Union, converted as the USSR had been into a great power following World War II. With China’s emergence, and even more so with the discrepancy between China’s line and that of the post-Stalin Soviet Union, these two poles of the socialist camp vied for influence in this peripheral South, which was becoming increasingly more central in global geopolitics.

Tricontinentalism channeled the interests of the national liberation movements in the face of this new order of superpower patronage, a system that until then had shaped their struggles along the prevailing bipolar configuration within the South itself. The road to the Havana conference in 1966 marked a turning point in the established Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organisation (AAPSO, known in Spanish as the Organización de Solidaridad de los Pueblos de Asia y África, or OSPAA), a point at which Southern actors sought to counterbalance competing East-West politics within the movement for liberation and self-determination in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The Tricontinental Conference crystallized this struggle and defined a concerted institutional order in which the alliance between the weaker players prevailed over the logic of superpower realpolitik in which the Chinese-Soviet pattern was rooted.

Havana was the natural home for this emerging challenge to bipolarity. In the 1960s, Cuba was at the height of its prestige and political and moral authority, especially within the broad anti-imperial movement. While Fidel Castro’s charismatic personality and his guerrillero image were influential, the country’s prominence owed a greater debt to more concrete factors. Cuba had achieved national liberation by its own means and had shown itself capable of defending itself and surviving on the border of the United States, which had supplanted Europe as the center of imperial power in the eyes of many nationalists in the Global South. Cuba was also resisting pressure to align either with China or the Soviet Union, claiming a path between these increasingly vitriolic poles of the socialist world. In so doing, Cuba projected a distinct socialist model and an independent foreign policy, which envisioned a unified anti-imperial left that respected self-determination and sovereignty, especially for small countries.Footnote 12

To understand the Tricontinental Conference is to appreciate this broader set of ambitions, rather than simplifying it as a meeting of armed conspirators and their sponsors. The conference was part of the movement’s arduous process of building political alliances. Whereas intelligence services, governments, and the established media limited themselves to identifying a meeting of subversives, in fact, it was an exercise in diplomatic dialogue between anti-hegemonic and progressive forces from most regions of the world, state and nonstate actors – legal and armed, atheists and believers, socialists, communists and independentistas.Footnote 13 The question of national liberation that was discussed is a topic far more expansive than insurgency or guerrilla warfare.

The declassified documents of the Tricontinental Conference shed light on this political process and its challenges and map out alignments and their reconfigurations.Footnote 14 According to these documents, the project of building an Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples from Africa, Asia and Latin America (Organización de Solidaridad de los Pueblos de Africa, Asia y América Latina, or OSPAAAL) – the permanent institution envisioned by the Tricontinental movement – faced three major challenges.Footnote 15

The first was the coordination of an anti-imperial agenda. This agenda encompassed the major themes of Tricontinentalism: in the words of the movement as expressed in the documents: “the fight against imperialism, colonialism, and neo-colonialism”; reaffirmation of a genuine peace agenda; and disarmament and peaceful coexistence for all, not only the great powers. For the Cuban hosts and many other delegations, the most important component of this struggle, one that should supersede all other issues, was unrestricted, multifaceted institutional support for the achievement and defense of national liberation. As explained above, national liberation was much more expansive than armed struggle.Footnote 16

The second challenge was to achieve an organization capable of providing this support through the development of active transnational solidarity. This support would transcend what some documents describe as the style and bureaucratic limitations experienced in AAPSO and other international democratic organizations, such as the World Federation of Democratic Youth. Expressions of alliance between the USSR and the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa had remained more symbolic than effective in solving the specific tasks of the movement.

The third was the Sino-Soviet divergence. Its impact on the movement will be explained in more detail later; generally speaking, it weakened the socialist camp. In regard to the conference, this divergence and the subsequent polar alignment of states and political organizations of all three regions made negotiations more complex. In the lead-up to the Havana Conference, the USSR and China both urged specific organizational and methodological additions to the program that had potential implications for the substance of future debate. For example, the Soviets advocated granting observer status – with the right to speak – to international organizations that they controlled. The Chinese opposed time limits on interventions in the plenary, and its representatives pushed to adopt accords by a two-thirds majority instead of unanimity, part of Beijing’s effort to advance more radical positions than state delegations aligned with the Soviet Union might have been willing to consider.Footnote 17 That vocal and disciplined minorities could hijack discussions was more of a threat to the event than any that could have been dreamed up by European and North America enemies or the authoritarian regimes in Latin America.

Most of the discussions at the conference focused on these three problems. But the third was the most pervasive and divisive, even to the point of influencing responses to the first two. Plenary sessions were extended beyond the regulations, taking time and energy from discussions in the commissions where specific and emerging tasks were to be considered, debated, and established. Among the most important of these “burning issues” were those cases that the conference defined as military occupations, such as South Vietnam and the Dominican Republic, both of which had recently become sites of American military intervention.

The Cuban delegation to the International Preparatory Committee (IPC) of the Tricontinental found that the Sino-Soviet split had turned AAPSO into an “arena of confrontation,” whose course shifted between two poles according to how the majority of the AAPSO aligned at any given time.Footnote 18 For instance, the United Arab Republic (Egypt) under Nasser aligned with the USSR; Pakistan and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea with China. African states, for their part, associated with one or the other according to the situation, and in many cases followed the lead of the National Liberation Movement (NLM) of their region or nation. Other signs of this matrix of contention were expressed by Japan’s distrust of supporting armed struggle, the condemnation of the United Nations as an “instrument of imperialism” by China, and the debate over whether Yugoslavia was a legitimate participant.

Despite these contentious issues, several benchmarks were met during preparation for the conference. When consensus on holding the event was reached in the AAPSO secretariat and its organization was started, the number of NLMs exceeded the number of states in the IPC for the first time. The entry of Latin America and the Caribbean, with five NLMs and only one state (Cuba), had changed the representation on the board of directors. Previously, AAPSO’s board composition had favored states –nine including the USSR and China over only six NLMs. In the lead-up to the Tricontinental, this predominance of states in the IPC (India, Guinea, Algeria, Tanzania, Indonesia, the UAR, China, and the Soviet Union) ended. The NLMs of the Latin American countries (Venezuela, Mexico, Guatemala, Chile, Uruguay), Cuba, and the remainder of the Committee (South Vietnam, Japan, South Africa, Morocco), constituted a new majority.Footnote 19 The NLMs had rather different commitments and were more independent from the influence of governments, although they also experienced alignment pressures from China and the USSR.

Another change in the lead-up to the conference was that the newly admitted Latin American NLMs galvanized the Preparatory Committee to modify the terms upon which national committees were established.Footnote 20 This move countered China’s motion, which advocated selection from the central communist parties in order to favor pro-Chinese political groups. This background, coupled with other disagreements between Cuba and China, heralded the shocks that would characterize the relationship between this host country and one of the largest delegations at the conference.

The significance of the OSPAAAL project itself assured that part of the agenda would focus on discussing OSPAAAL’s constitution, a topic that attracted many to the Organizing Committee. The idea of creating a Tricontinental organization was not an end in itself but, rather, a political instrument to strengthen the NLMs and consolidate a united front against the violence of the United States and its allies in Indochina. Fundamental variants were many and debated. The USSR advocated replacing AAPSO with OSPAAAL. China wanted to retain the AAPSO and create a complementary Organization of Latin American Solidarity (OLAS). The United Arab Republic was willing to adopt OSPAAAL but wanted it headquartered in Cairo. Latin American representatives desired that a new OSPAAAL be based in Havana, with AAPSO remaining independent.

According to the confidential report of the Cuban delegation, its strategy was not defined by any preconceived formula to create the Tricontinental. Havana’s main goal was to reach an agreement on building a balanced structure for the new organization without harming the unity of the movement. In their position between the competing Soviet and Chinese factions, Cuban delegates tried to moderate the antagonistic positions of every actor, including themselves: “We did not reject the possibility that the Tricontinental would have its headquarters in Havana, but we did not fight for it at all costs.”Footnote 21

The Cuban strategy was to avoid discussing every issue in the plenary, where confrontations became very heated. Instead, they negotiated bilaterally with key actors of various sizes – large (USSR, China), medium (UAR), and small (African and NLMs) – which had various types of influence, as well as with allies (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, South Vietnam’s National Liberation Front, and the Pathet Lao). Following the leadership of their representatives at the conference, the Cubans deployed the flexible diplomacy necessary to win over both pro-Chinese countries like Sukarno’s Indonesia and others like Guinea, which depended heavily on Soviet aid. In deploying this bilateral negotiation strategy at different levels, their key method was to demonstrate that they sought consensus above everything else. These examples illustrate the extent to which the seven-year-old Cuban government – under an intense US siege and almost totally isolated in the hemisphere – felt compelled to develop ties with a diversity of ideological and geopolitical actors on four continents and thereby both garner international respect and expand Havana’s global influence.

One such issue was the question of armed struggle, which outside observers have emphasized but which was actually discussed only a little within the conference. This inattention may have been because, with a few exceptions, most of the participants had accepted that armed revolt was necessary in certain situations where colonialism and imperialism were defended with violence. Though the Soviet Union and its closest allies expressed a preference for peaceful coexistence, many of the influential – if smaller – nations present had come to power after bloody struggles, as was the case for Algeria, Cuba, and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Moreover, many delegations from armed movements that were fighting for national liberation or preparing to do so at the time, such as Venezuela, South Vietnam, Zimbabwe, South Yemen, Palestine, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Laos, Guatemala, and South Africa were attending the conference.

The global geopolitical circumstances also furthered widespread sympathies toward various types of violent resistance. In 1965 alone, the United States had landed troops en masse in South Vietnam, while American forces and their Latin American allies occupied the Dominican Republic. Ongoing revolutions in Mozambique and Angola, supported by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), sought to oust colonial Portugal, which benefited greatly from membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).Footnote 22 As a result, progressive political and intellectual circles in Europe and the United States did not immediately reject armed nationalists as terrorists or as bellicose, especially in the case of Vietnam. Public figures like Lord Bertrand Russell sent emissaries to Havana to make contact with the national liberation movements and the Cuban government. Within two years of the Tricontinental, the assassination of Che Guevara in Bolivia would further arouse world opinion and produce a wave of admiration for the causes of anti-colonialism and national liberation, extending a political climate that made room for armed revolt as a legitimate strategy for the disenfranchised. Indeed, the 1960s and beyond saw a rise in perceived disenfranchisement in the North as the Cold War initially entrenched hierarchical societal and governmental structures that were perceived as restrictive and objectionable. Activists in the North increasingly looked to the South for inspiration, as role models and as evidence that a new world was possible or even probable. Actors in the North practiced solidarity of deed such as protests, international visits, and fundraising in support of revolution in the South. Many on the left, even those perhaps skeptical of particular national governments in the South felt and acted upon what might be loosely called elective affinities or transnational solidarity.

The differences around armed struggle that arose in conference deliberations did not reflect a general reluctance to acknowledge the legitimacy of this strategy. Rather, some organizations and governments were reticent about excluding other forms of political struggle, namely participation in electoral politics. Many delegations to the conference consisted of individuals who did not advocate guerrilla war, such as the socialists Salvador Allende of Chile, Heberto Castillo from Mexico, the Argentinian John William Cooke, and the former premier of British Guiana Cheddi Jagan, as well as the delegations from Uruguay, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Haiti, to speak only of Latin America and the Caribbean. The image of the conference as comprised solely of violent groups was a caricature broadcast by its enemies,Footnote 23 whether by design or through ignorance.

Other central themes that occupied the discussion in the commissions were US imperialism’s role in culture, as well as relations with mass organizations such as unions, student, and women’s groups that were invited to participate in the conference.Footnote 24 The impact of the sessions devoted to economic, political, and cultural topics was felt beyond the halls of the conference, the tendency to caricature the event notwithstanding.

It must be said that the persistence of these stereotypes and prejudices was not confined to the Western governments, or the far-right wing. In those years and subsequently, Cuban students in Eastern Europe and the USSR had to suffer them on many occasions. The representation of the Tricontinental as an encounter of extremists and romantics, and of Che Guevara as an idealistic adventurer obsessed by war and lacking in profound ideas, was common in Soviet political culture then, even in the universities. Many Eastern Europeans who knew the island recognized that Cubans lived their revolution differently and that in addition to passion and patriotism there was a civic culture full of thought and discussion; however, visitors from Eastern countries, journalists, civil servants, and even artists and writers did not always penetrate beyond the epidermis or understand Cuban society. The negotiations between Cuba and the two Germanies around the Tricontinental variously demonstrate romanticization, solidarity, and national political aims on the part of the Germans. Of interest in their own right, these engagements demonstrate the complexity of the Tricontinental and illustrate attempts by Cuba to move beyond the bipolar world desired by some of the most powerful nations.

The Tricontinental and Cuba through German Eyes

The ideological and political diversity of the participants and observers was expressed in the range of their perceptions and interpretations of the Tricontinental. The German example is an under-recognized case in point. The socialist GDR, the capitalist FRG, and activist groups in the FRG – the West Berlin anti-authoritarians, for example – each interpreted the conference, Cuba’s actions, and their own position relative to their particular interests, aims, and desires. Although they were in different worlds, the GDR in the Second World and Cuba in the Third World, each negotiated toward an alliance by highlighting the similarities of their geopolitical circumstances in the polarizing world of the Cold War. Meanwhile, the left-leaning student activists in the First World styled themselves as being in circumstances analogous to those of the Cubans. And left-leaning Germans on both sides of the Wall came together over critiques of neocolonialism and Third World solidarity.

An overview of the relative positionings of the Tricontinental Conference participants shows the complexity of the political enlacements among these three worlds. Since the Tricontinental was, by definition, regional and excluded Europe, North America, and Australia, most participant delegates (full members) came from Asia, Africa-Middle East, and Latin America. As has been pointed out, some of them represented national liberation movements, but many others did not. The delegations from Chile, Argentina, Algeria, Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Korea, Ecuador, Ghana, and Guadeloupe, for example, represented official state governments or political factions that had yet to adopt ambitions for political insurrection. The AAPSO had also recognized solidarity organizations from the USSR, the People’s Republic of China, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and even from Japan as full members. Apart from the DRV, they were not related to any national liberation movement. The two largest delegations to the Havana conference came from China (34) and the USSR (40), which added to the political complexity of the Tricontinental fabric; it was well known that the Sino-Soviet divergence was over more than a simple dichotomy of armed struggle versus peaceful coexistence. As for the Second World, seven solidarity organizations attended the conference as observers. With seven representatives, the largest delegation came from the GDR.

Like other Soviet-aligned socialist countries in Europe and the Soviet Union itself, the GDR saw in the Tricontinental Conference and in Cuba an opportunity and a danger, which several key documents show. The meeting on February 15, 1966, of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the GDR’s ruling Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED) in Berlin includes an analysis of the conference. The report highlights principled successes of the GDR delegation there. It articulates GDR and socialist state aims of aligning the Tricontinental and Cuba toward the Soviet Union and Marxist-Leninism. It emphasizes the GDR’s allegiance to the Soviets by describing the delegation as particularly active in working to meet these goals, for instance by strengthening long-standing relationships and developing new ones. It also asserts that the GDR received extensive recognition from the anti-imperialist movement, for instance State Council Chair Walter Ulbricht’s telegram was one of the first read to the attendees and was warmly received.Footnote 25

A full, polyadic analysis could thoroughly consider GDR relations with the FRG and NATO countries, the USSR, and the Eastern European socialist camp, the Third World and Latin America (as arenas of confrontation with its enemies), and with Cuba; this essay will focus on the Politburo’s assessment of the Cuban role in the Tricontinental. The report emphasizes Cuba’s socialist bent and its allegiance with the Soviet camp. It states that “having the conference in a socialist country like Cuba gave it an importantly positive impetus.” In preparation for the conference, it continued, there was increasing agreement between the Cubans and the USSR, “although the Cubans emphasized the necessity to make tactical concessions so that the Chinese could not achieve their aims [nicht zum Zuge kommen könnten].” According to this official report, then, the Cubans collaborated with the Soviets in order to better negotiate Chinese tactics that sought to unduly influence the conference’s political objectives and definitions. This perception is consistent with the tensions reported by the Cuban delegation vis-a-vis the Chinese line in the planning and organization of the conference, and particularly in regard to the independent role that Latin America sought toward the new OSPAAAL. In the Tricontinental context, the Cuban government perceived these Chinese policies as an expression of hegemony that put pressure on Third World actors – national liberation movements in Latin America and Africa, as well as socialist countries such as Vietnam and Cuba itself – to align with Beijing, thereby limiting their diplomatic freedom. One stark example is that during this period Mao Zedong was using trade mechanisms – namely aid shipments of rice – to try to force Cuba to join the pro-China communist faction.

The Cuban position was much more complicated than the East-West geopolitical equation, particularly the zero-sum game that largely defined the GDR’s situation. After all, the Cuban-Soviet alliance remained on rocky ground as well. Three years after the Missile Crisis of 1962, Cuba did not trust the Soviet Union’s political support; it was skeptical that the geostrategic umbrella that protected the GDR and the European socialist camp would provide any protection to Cuba. The following quote from the report about Cuba’s actions at the conference merits detailed consideration. Although as we will see further on, Cuban and GDR diplomatic discourse emphasized parallel geopolitical narratives between the island and East Germany, both countries experienced quite different circumstances. These on-the-ground differences help explain why this report assesses the Cuban position in the conference as exceptionalist:

[The Cubans] overemphasized the importance of their so-called own experiences in armed liberation struggle for the entire movement. Upon this they based their claim to lead the movement. They were patronizing to the other delegates and went as far as a break with the SU, to intrigues against representatives of the communist party of Latin American, and to eliding the role of the SU in speeches and in the drafting of documents. The Latin American movement of armed struggle under the leadership of Cuba was deemed as having higher quality than that of the struggle of the African peoples.

The African, Arabic, and Indian delegates were deeply perturbed and angered with the Cuban position and threatened in part to leave the conference early.

The Cuban position threatened the success of the conference, threatened the unity of the anti-imperial movement, and hindered a decisive rejection of the Chinese attempts at obstruction [Störversuche].

The document further states that Cuba insisted upon making Havana the seat of the Tricontinental, which also hindered cooperation. It goes beyond the scope of this investigation to determine whether Cuba’s or the GDR’s reporting on this position and its effects is more accurate; the fact that the GDR decried Cuba’s actions in this regard points to tensions between the two. The Cubans’ actions are portrayed as an impediment to the cohesion of the event: arrogant, overbearing, and excessively patriotic. The depiction of the Cubans as divisionaries may be interpreted as official GDR discontent about Cuban actions that would move the conference outside of the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union. It demonstrates that the positions of the GDR and Cuba were quite distanced. The GDR considered its present and future to be with the Soviets, while the Cubans considered both the Soviets and the Chinese to be distractions.

As we will see, however, other official documents from the GDR highlight similarities between the Cuban and GDR positionalities. These seeming dichotomies show us that there were many aspects to the GDR’s relationship with Cuba. This example of complex relations between the Third World country of Cuba and the Second World country of the GDR also functions as a corrective to the commonly held myth of bipolarity at the conference and beyond. The document to which we now turn suggests that the GDR understood Cuba better than some other Eastern bloc countries due to its own positioning on the West-East border and its assessment of Nazi Germany’s and the FRG’s actions as imperialist. These situations were not abstract for them. Furthermore, the GDR could leverage these parallels as a means of influencing Cuba, which was its aim at the Tricontinental Conference. Cuba and others were skeptical of the USSR; by winning over Cuba, the GDR could garner favor with the USSR and gain power on the world stage.

A memorandum on a follow-up meeting to the conference on July 20, 1966, between a GDR delegation visiting Havana for the 26th of July commemoration and representatives of the Tricontinental movement’s executive committee shows how both sides emphasize parallels between Cuba and the GDR. Each side depicts these similarities as reasons to support closer alliance and cooperation. The Guinean representative and leader of the meeting, Kouyaté, explicitly describes European issues and the German Problem as central to joint concerns. Further, the Cuban representative is reported to have invited the GDR representatives to a July symposium “condemning the war of mass destruction against the Vietnamese, at which the role of ‘West German imperialism’ would also be exposed.” GDR diplomat Dieter Kulitzka highlights the connection in his assessment:

The Executive Secretariat’s unmistakable allusion that our national mission is to be supported to the extent that we take seriously and further the Tricontinental Movement must be seen as noteworthy. Seemingly (and certainly rightly) the struggle against West German imperialism is deemed an effective main point of connection [Hauptanknüpfungspunkt] between the Tricontinental Movement and the GDR. Precisely this commonality was also especially emphasized in Comrade Ducke’s [representative of the Afro-Asian Solidarity Association] statements.Footnote 26

In the 1960s, left-leaning thinkers commonly labeled the FRG’s agenda as imperialist based on its participation in NATO, its bellicose attitude toward the GDR, and its support for US military actions around the world.Footnote 27 Both the Cubans and the GDR saw parallels in the “hot” aggression of the United States and the “cold” aggression of the FRG. We have seen that the Tricontinental Conference itself categorized armed and unarmed aggression differently; hence at least some of the emphasis on the similarity should be seen as a means to further ties between these countries on different sides of the North-South division.

The GDR’s engagement with the Cubans and the Tricontinental movement also aimed to augment the GDR’s importance among the Warsaw Pact countries and the Soviets. The socialist German nation may have considered it beneficial to show these Southern players with whom it seemed to have some influence in a politically beneficial light. Kulitzka’s report carefully outlines the structure of the Tricontinental and makes its mission clear without highlighting its interest in armed struggle, from which the Soviet Union had distanced itself after the conference. Kulitzka describes Kouyaté’s words on this matter, which smooth and diminish the tension without dismissing it:

The Tricontinental Movement is, just as the socialist countries are, determinedly decided for world peace. Its way to achieve its goal is not by means of a world war, although the way of the Tricontinental Movement is militant [kämpferische].

In this statement Kouyaté seeks to mitigate potential objections to militancy through clever formulations. Such phrasing may be tactical vis-à-vis (mistrustful) representatives of socialist nations and, also, expresses contradictions within the Tricontinental movement itself.

While discussions among socialists such as the one described in the documents above make clear that Tricontinentalism did not need to be seen as requiring armed rebellion, the perception of Cuba as a revolutionary state continued to stoke international fears. In the immediate wake of the Tricontinental Conference, many Latin American governments reacted against what they perceived as a potentially violent communist threat in the heart of the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (commonly known as the Rio Pact or TIAR in Spanish). By January 25, 1966, Peru had called for a special session of the Organization of American States to protest the conference’s final resolution, accusing the Soviet Union and Cuba by name. Venezuela was adamant in its complaint. The government of the Dominican Republic barred its delegates from reentry on the charge that while in Havana these participants had stated their aim to hinder voting and to start a new civil war modeled on Vietnam. It is, of course, useful to keep in mind here that most of these Latin American governments were under authoritarian or military control that they sought to maintain against popular support: Argentina (1966–73), Bolivia (1964–66), Brazil (1964–85), Ecuador (1963–66), Paraguay (1954–89), El Salvador (1931–82), Guatemala (1957–66), Honduras (1963–71), Nicaragua (since the 1930s), among others. Moreover, the Dominican Republic was militarily occupied by the Inter-American Peace Force when the conference took place, with no civilian president-elect, but military rule by two generals, one Brazilian and one American. Of course, these military regimes were unhappy with the Tricontinental, even if some would engage with similar politics in the future.

While the GDR was participating in the conference and developments stemming from it in the manner sketched above, the FRG was bound by the Hallstein Doctrine – which meant it could not recognize Cuba because of Cuba’s diplomatic relations with the GDR – and by restrictive US policies toward Cuba. Restricted by this Cold War legislation, it watched attentively from the sidelines. Accordingly, archival material from the Federal Republic consists primarily of communiqués from German embassies about the conference. A report dated February 4, 1966, from the German embassy in Montevideo highlights the GDR as an important, and, importantly, more palatable representative in Latin America than the Soviet Union. According to this document, Uruguay had been adamant over its concern about the conference resolution and “the SU’s expressed desired role in Latin American armed struggle.” Although Uruguay is a “main bridgehead [Hauptbrückenkopf]” for the Soviets in Latin America, the report states, Uruguay’s signing of the joint protest petition should be a warning for the Soviet Union to avoid an obvious presence in Uruguay. This West German description of the conservative Partido Nacional government in Uruguay as an ally of the Soviets, who were on the other side of the political spectrum, and of the Soviet policy as supporting armed struggle in Latin America reflects a typical Cold War shortsightedness. Moreover, as in the East German examples above, such reporting from the FRG shows that Bonn’s main concerns around the Tricontinental Conference were its own German-German affairs and, relatedly, that both Germanies saw the potential for a special relationship between the GDR and Cuba.

Among the FRG populace, interest in Cuba and the Tricontinental also accorded with its own concerns. While left-leaning GDR citizens may have felt that their government did not go far enough in their collaboration with or emulation of Cuba, left-leaning FRG citizens disagreed with the position of their leaders. In some ways the situation in West Germany recalled leftist liberation movements who visited the Tricontinental Conference and, to the chagrin of those formally in power, left energized to unsettle their governments back home. The West Berlin anti-authoritarians are an example of the Northern political groups who were inspired by the Tricontinental and its support of armed violence, perhaps inordinately so. They had no first-hand experience with the pain of such struggle after all. The anti-authoritarians did not attend the conference, but they followed it, the Tricontinental Organization, AAPSO, OSPAAAL, and the OLAS, as well as many activist and liberation organizations of the Third World, closely. In parallel with Cuba’s situation, they saw the relationship between West Berlin and West Germany and West Germany and the United States as neocolonial. After all, the Federal Republic of Germany was being built up as a primary US trade and strategic ally in Europe through the Marshall Plan and the stationing of American and NATO troops in the FRG.Footnote 28 Indeed, as Jennifer Ruth Hosek has shown in detail elsewhere, the anti-authoritarians – mostly students, and famously led by Rudi Dutschke – strategized/fantasized about “liberating” West Berlin using the foco theory made famous by Che Guevara.Footnote 29

Deeply skeptical of fascist nationalism, these youths were nevertheless inspired by the revolutionary nationalism espoused by the non-aligned movement since the 1950s and articulated at the conference. They identified with what Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri call subaltern nationalism: “whereas the concept of nation promotes stasis and restoration in the hands of the dominant, it is a weapon for change and revolution in the hands of the subordinated.”Footnote 30 These Northern students and intellectuals embraced subaltern nationalism and sought alignment with Third World groups. The protests that they undertook in Berlin were informed by and in solidarity with Southern struggles. They were inspired by Guevara’s 1967 call for multiple Vietnams as they resisted their government’s move to the right and crackdown on dissent. Their take on the Tricontinental and the movement it sought to create may have been one that exaggerated its emphasis on armed struggle while also expressing an affective solidarity with the Global South.

More generally, the relationships of leftist activists in the North with liberation struggles in the South may be seen as a solidarity of the type for which conference participants strove translated into a Northern register. These connections are often understood as revolutionary romanticism, perhaps leading, in extreme cases, to domestic terrorism. While attending to this criticism, recent scholarship has been investigating practices of solidarity across North and South that exceed the physical and the cognitive. It explores the political significance of affective relationships – sympathy, empathy – in the absence of international relations between states or organizations and a critical mass of support for political action.Footnote 31 While their results will be different and perhaps not immediately massively influential, taking them seriously can enrich understandings of solidarity and its potential for creating change.

Significantly, dismissals of Southern-inspired liberation movements in the Global North have tended to coincide with the end of broad-scale state socialism and a concomitant sense that perhaps socialism itself has failed. In the German case, established left-leaning scholars have been levelling self-criticism since the mid-1980s. As the Soviet bloc became destabilized, many reassessed their interest in and work with Third World issues and found them lacking. A related critique noted that transnational solidarity allowed Northerners to align on the politically emancipatory side of history and escape their guilt about their own national pasts by identifying with the victims and/or translating this guilt into responsibility for neocolonialism. Many of these intellectuals had also moved politically to the right, into the fold of the dominant society. Therefore, in making this self-critique, the now well-established 1960s generation shifted from what had become the “losing” side.Footnote 32 In contrast, scholars without direct experience with – and unconvinced of – the state socialisms of the Cold War and yet hoping for something better are investigating the possibilities opened by the limited solidarity of privileged Northerners: for instance, that affective solidarity and identification drove emancipatory political actions of the West Berlin anti-authoritarians; for instance, as Robert J. C. Young argues, that postcolonial theory itself – an influential model of thinking based in non-Western political and cultural production – would seem to have originated at the Tricontinental Conference.Footnote 33

Conclusion

Each of the stakeholders in the Tricontinental project had a particular agenda for the conference and for shaping North-South anti-imperialist and Cold War strategies. Cuba was deeply involved before and after the conference in negotiating the tensions and infighting between anti-imperialist and socialist liberation movements and parties, national governments, and the major powers of the Soviet Union, China and, indirectly, the United States. German actors – the GDR, the FRG, and the West Berlin anti-authoritarians – present particularly interesting cases of interaction with Northern actors. German positioning at the borders of the Cold War conflict in Europe led to the two governments being particularly interested in how the conference and GDR relations with Cuba could increase Southern solidarity with the German-German problem and improve their statures on the world stage. The anti-authoritarians exemplify a Northern-based liberation group inspired by Southern anti-imperialist theory and practice. Variously considered dilettantes and dangerous rabble-rousers, their domestic, progressive political actions were fueled by their assessment of the Tricontinental and Cuba. While the conference is often viewed as a South-South attempt to foment revolution, it was far more ambitious and complex in terms of its goals, structures, and membership. Not only did armed revolution constitute just a single goal of Tricontinentalism, but the conference and broader movement centered on uniting global anti-imperial forces. This focus encompassed not just countries of the Global South but also socialist bloc states and sympathizers in Western countries disillusioned by what they saw as unjust foreign policies of their homelands, specifically their approach to the Global South.

This essay has focused on the strategic interpretations and practices of Cuba, one of the main organizers of the conference and key actors in the Tricontinental movement; on the perceptions of the GDR, not a member of the movement, but rather an observer in the Tricontinental framework, and also an actor aligned with the Soviet Union in the East-West bipolar system; and has touched on the strategic interpretations of the FRG, a spectator interested, as was its sibling nation the GDR as well, in the impact of the Tricontinental on the German problem. Additional comparison with a group of activists who avidly read Third World texts in their Northern cities and sought solidarity in emulation may have seemed irrelevant, governed as they were by affect and elective affinity. Consider, however, this comment from Markus Wolf of the GDR’s secret service for international affairs upon an official visit to Havana in January 1965, an indication that even the line between affective solidarity and strategic intelligence is neither straightforward nor bound by national borders:

The Cuban comrades have only these words in their mouths, “before the revolution ….” It’s what they have really done, beneath the sun of the tropics. While we, the others, in the grey daily grind, have moved from the rubble of Nazism to socialism in the trucks of the Red Army.Footnote 34