Home gardens have existed for centuries, but research on them is relatively rare in developed countries(Reference Taylor and Lovell1–Reference Galhena, Freed and Maredia3). The few published studies on home gardening in the USA are pilot studies(Reference Bail, Fruge and Cases4) or mixed methods studies in a single community(Reference Taylor and Lovell1,Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5,Reference Taylor and Lovell6) . These studies suggest that home gardens may offer a range of benefits similar to those observed in community gardens(Reference Taylor and Lovell1,Reference Porter2,Reference Draper and Freedman7–Reference Garcia, Ribeiro and Germani9) , including increased fruit and vegetable intake(Reference Bail, Fruge and Cases4,Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5,Reference Algert, Diekmann and Renvall10) , physical activity(Reference Bail, Fruge and Cases4,Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5) , social capital(Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5,Reference Taylor and Lovell6) , food security(Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5,Reference Taylor and Lovell6,Reference Algert, Diekmann and Renvall10,Reference Kortright and Wakefield11) and connections to cultural heritage(Reference Taylor and Lovell6). In an evaluation of a home gardening initiative in San Jose, CA, participants reported increased vegetable consumption, gardening-related physical activity, cost savings and new and strengthened connections with neighbours(Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5). Bail et al.(Reference Bail, Fruge and Cases4) observed increased physical activity in a pilot study of home gardening among cancer survivors and a trend towards increased vegetable consumption. Taylor and Lovell(Reference Taylor and Lovell6) described a mixed methods study of home gardens in Chicago. Qualitative findings suggested that home gardens contributed to household food budgets by reducing the need to purchase vegetables during the growing season and the practice of preserving the harvest through freezing. Sharing of produce was common, and gardening served as a means of continuing cultural practices through food (e.g. growing collards, chillies or bitter melons).

Gray et al. (Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5) discuss how home gardens are emerging as a potential new strategy within the food justice movement due, at least in part, to barriers to community gardens in urban settings, including high property values, long waiting lists for participation and the challenges of time and transportation to community locations for low-income households. Thus, gardening can not only encourage a more nutritious diet and increased physical activity but also has the potential to address food access and food security, especially when fresh produce may not be available or accessible due to cost and distance(Reference Taylor and Lovell1,Reference Draper and Freedman7,Reference Algert, Diekmann and Renvall10–Reference Eigenbrod and Gruda12) .

Studies that have examined the prevalence of home and/or community gardening show a much higher rate of home-based over community gardening among the general population(Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles13). A study by the National Gardening Association showed that 35 % of households in the USA grew food in 2013(14). The vast majority of those gardened at home (88·2 %). To our knowledge, no national studies have examined the associations of home gardening with fruit and vegetable intake or BMI. Understanding who has home gardens in the USA and whether gardens are associated with nutrition and weight-related outcomes will help to lay the foundation for future efforts to use home gardens as a potential intervention strategy for obesity prevention.

Methods

Data used for the current analysis are from a cross-sectional, national home food environment survey administered in the fall of 2015 to participants aged 18–75 years, living in the USA and capable of reading English. Quotas were used in order to increase national representativeness in terms of age, gender, race and ethnicity, income and geographic region. Participants were recruited via email through Lightspeed Global Market Insite (GMI), using their existing panellist profile data (http://www.lightspeedresearch.com). Participants provided consent and then started the survey which took approximately 30 min to complete. The study protocol was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

A total of 4942 individuals completed the survey (39·9 % of those consented); the remainder of panel members who initiated the survey process were deemed ineligible due to quota requirements (30·7 %), only completed part of the survey (24·2 %) or were terminated by Lightspeed GMI due to in-survey quality control checks (5·2 %). The analytic sample for the primary analyses reported here (n 3889) additionally excludes those for whom addresses could not be geocoded (n 726), those who had invalid fruit and vegetable intake responses (n 193) and those with missing values on key study variables (n 134).

Measures

Gardening. The presence of a home garden was assessed by asking: ‘The next questions are about home gardens: do you (or anyone in your household) grow edible plants in a garden?’ with response options ‘yes’ and ‘no’. The presence of edible plants in containers or pots was also assessed.

Neighbourhood type was assessed by asking respondents to indicate whether the area in which they live is rural, a small town, suburban or urban. Social capital was assessed at the neighbourhood level using a seven-item measure(Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls15). A higher score indicates higher social capital.

Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Geocodes and county names were assigned to each residential address in the data set using the geocode feature in Google Earth Pro©. In cases where an address was not identified using Google Earth Pro©, it was supplemented with Census-identified counties and geocodes using the address locator tool on the Census website(16). Each observation was assigned a Rural-Urban Continuum Code (RUCC) which is a categorisation scheme that classifies the US counties into three metro and six non-metro categories(17). RUCC were collapsed into three categories of counties: (i) urban (1–3), (ii) semi-urban (4–6) and (iii) rural (7–9).

Fruit and vegetable intake. Fruit and vegetable consumption was measured using a National Cancer Institute screener that asked about frequency and quantity of consumption of fruits and vegetables (e.g. lettuce salad and tomato sauce)(Reference Thompson, Subar and Smith18,Reference Subar, Thompson and Kipnis19) . Daily intake in cups was calculated, and values above three times the interquartile range were excluded. The variable was dichotomised for use in regressions as ‘Not Meeting Recommendations’ (<4·5 cups/d) or ‘Meeting Recommendations’ (≥4·5 cups/d) based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020(20).

Weight status. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using participant-reported height in feet and inches and weight in pounds, as adapted from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System(21).

Demographics. Socio-demographic information was collected including age, gender, race/ethnicity, state of residence, employment status, educational attainment, marital status, household size, composition and income(21,22) .

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.). T tests and χ 2 tests were used to explore the relationships between participant characteristics and presence of a home garden. Generalised estimating equation (GEE) models were used to control for the effect of clustering at the county level. Generalised estimating equation models assessed associations between (i) demographic variables and presence of a home garden, (ii) presence of a home garden (primary exposure variable) with binary fruit and vegetable intake (meeting/not meeting recommended intake) and (iii) presence of a home garden with continuous BMI. The models were adjusted for gender, age, race, income and level of rurality. As sensitivity analyses, we (i) compared the findings from our analytic sample (which was reduced due to geocoding) and the full sample and (ii) looked at fruit and vegetable intake as a continuous measure both in its raw metric and log transformed for the multivariable models.

Results

Description of respondents

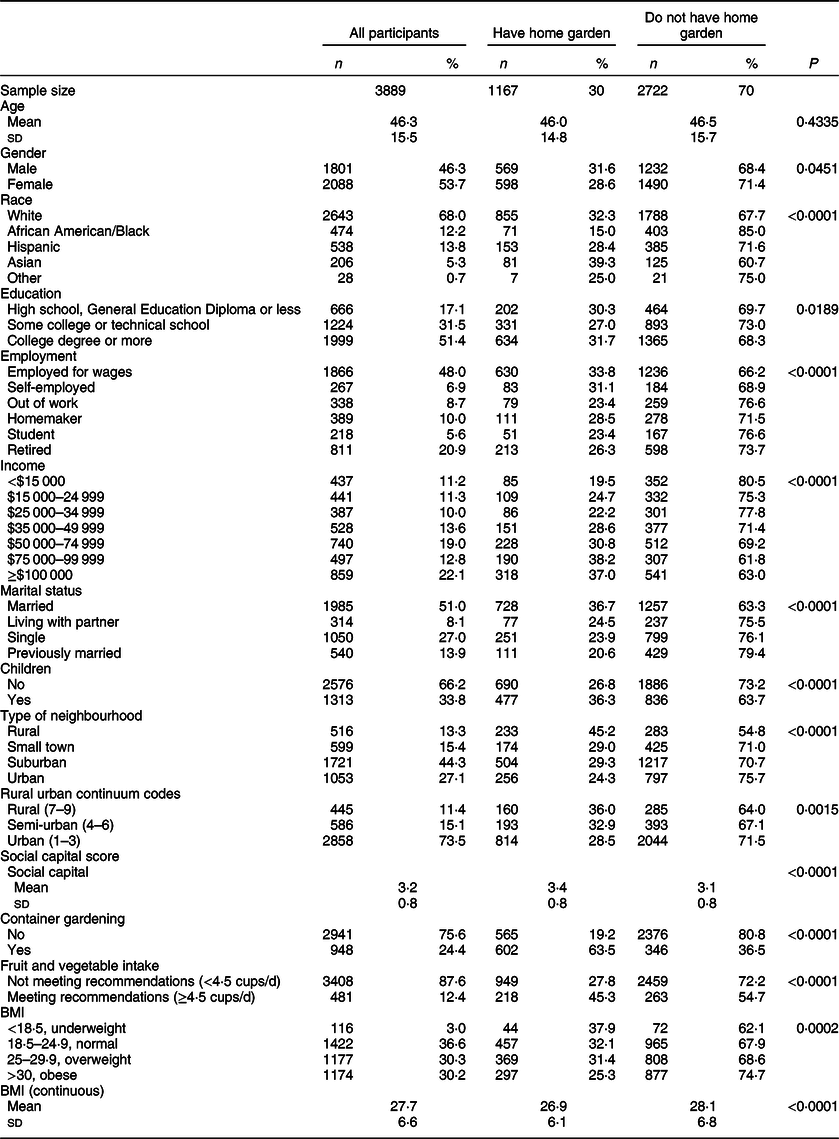

The average age was 46·3 (sd 15·5) years, with 53·7 % women. African Americans, Hispanics and Asian Americans comprised 12·2, 13·8 and 5·3 % of the sample, respectively, with 68·0 % White (Table 1). Over half had a college degree (51·4 %). Approximately 11·2 % lived on annual household incomes <$15 000 and 22·1 % on ≥$100 000/year. Over half were married (51·0 %) or living with a partner (8·1 %), and 33·8 % had children in the home. Almost three-quarters (73·5 %) lived in urban areas defined by RUCC 1–3. The majority did not meet recommended guidelines for fruit and vegetable consumption (87·6 %). Mean BMI was 27·7 (sd 6·6) kg/m2, and 30·2 % were obese. Thirty percentage of participants reported a home garden that produced edible plants. Of those with no home garden, 12·7 % grew edible plants in a container.

Table 1 Description of survey respondents by home garden status

Associations between demographic characteristics and home gardens

Table 1 presents bivariate associations between those who have a home garden and those who do not. The presence of a home garden varied significantly by all variables examined, with the exception of age. Asian Americans were the most likely to have a garden (39·3 %), followed by Whites (32·3 %), Hispanics (28·4 %) and African Americans (15·0 %). Those with a college degree were slightly more likely to have a garden (31·7 %), as were those who were employed (33·8 %) and with higher annual household incomes. Participants who were married (36·7 %) and had children at home (36·3 %) were also more likely to have a garden.

Rurality was associated with home gardens; 36·0 % of residents within counties with a RUCC of 7–9 reported a garden in contrast to 28·5 % in urban counties (RUCC of 1–3). Similar patterns were observed for self-described neighbourhood types; 45·2 % of respondents in a rural area reported a garden in contrast to 24·3 % in urban areas. Social capital was significantly higher among those with a home garden (P < 0·0001). Those with a home garden were more likely to meet fruit and vegetable intake guidelines (P < 0·0001) and had lower BMI (26·9 v. 28·1, P < 0·0001).

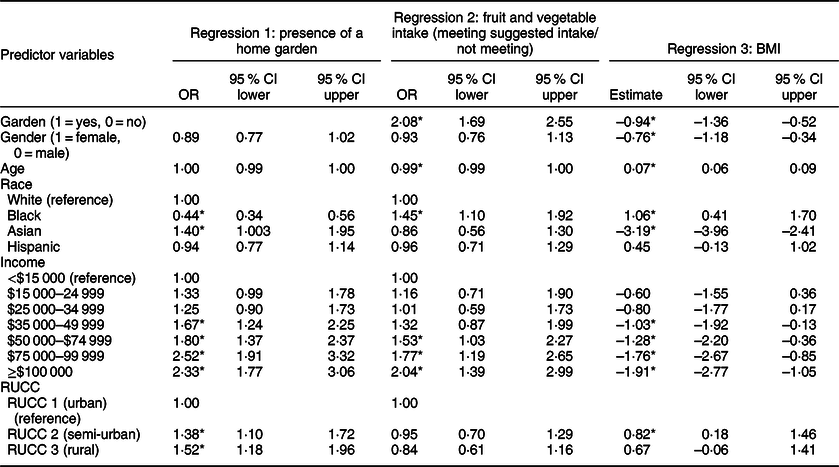

In the multivariable model (Table 2), results show that several bivariate associations remained significant. Specifically, African Americans are less likely to have a home garden than Whites (OR 0·44, 95 % CI 0·34, 0·56), and Asian Americans are more likely to have a home garden than Whites (OR 1·40, 95 % CI 1·003, 1·95). Households with higher annual incomes are more likely to have a home garden than those with an annual household income <$15 000. Those with an income >$74 99 were more than twice as likely to have a home garden than those in the lowest income category. Residents of semi-urban counties and rural counties are more likely to have a home garden than urban residents (OR 1·38, 95 % CI 1·10, 1·72 and OR 1·52, 95 % CI 1·18, 1·96, respectively). Sensitivity analyses showed that the findings did not differ qualitatively (i.e. the same significant relationships remained) when including participants whose addresses could not be geocoded in the analyses see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1), except for age where the difference between the groups (i.e. with and without a home garden) was larger in the full sample and reached significance.

Table 2 Generalised estimating equation regression results for the presence of a home garden, fruit and vegetable intake and BMI (n 3889)

RUCC, Rural-Urban Continuum Code.

* Significant at the 5 % level.

Multivariate models of fruit and vegetable intake and BMI

The second multivariable model examines associations of home gardens with fruit and vegetable intake. When controlling for demographics and rurality, home gardens are associated with more than twice the odds of meeting national guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake (OR 2·08, 95 % CI 1·69, 2·55). The significance and directionality of effects did not differ for fruit and vegetable intake when modelling it as a continuous variable in its raw metric or log transformed (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2). Home gardens remained a significant predictor in both models.

The third multivariable model examines associations of home gardens with BMI. When controlling for demographics and rurality, BMI is significantly associated with home gardening in the expected direction (b = –0·94, 95 % CI –1·36, –0·52), indicating a lower BMI among those with a home garden.

Discussion

We found that 30 % of respondents in our study had a home garden. This is almost the same as the National Gardening Association finding that 30·8 % of US households garden at home(14). In our study, home gardens were more common among individuals living in rural areas, as well as among those who had children in the home, were employed, had higher annual household incomes and had greater educational attainment. That said, one-quarter of participants with lower incomes and/or no employment reported a home garden, suggesting that gardening is feasible for low-income households. Results from the National Gardening Association survey corroborated our findings that income was associated with gardening; importantly for public health, they also documented growth in gardening among low-income residents from 2008 to 2013(14). Higher rates of gardening in rural areas may be due to family traditions and culture, distance to towns with supermarkets and farmers markets and readily available land. Urban living may be less conducive to home gardening due to lack of space, costs associated with raised beds or concerns about prior uses of the land and possible soil contamination(Reference Hunter, Williamson and Gribble23).

Consistent with research on community gardens and fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles13,Reference Twiss, Dickinson and Duma24–Reference Barnidge, Hipp and Estlund27) , we found positive associations between home gardening and fruit and vegetable intake(Reference Bail, Fruge and Cases4,Reference Gray, Guzman and Glowa5) . We also found that home gardens were associated with lower BMI. Research on gardening and BMI is rare; Zick et al. (Reference Zick, Smith and Kowaleski-Jones28) found that community gardeners in Salt Lake City had lower BMI than their siblings and neighbours. Bail et al.(Reference Bail, Fruge and Cases4) examined weight and BMI among cancer survivors in a home gardening intervention but found no impact on either. Consistent with other studies, we saw a positive association between gardening and higher social capital(Reference Draper and Freedman7).

The current study has several limitations. Data are cross-sectional thereby limiting our ability to disentangle whether gardens are causally linked to fruit and vegetable intake and lower BMI. Data are also self-reported and may be vulnerable to social desirability bias. For example, weight may be under-reported. In addition, due to the use of an online recruitment panel service, US adults without internet access would have been systematically excluded from the current study.

The current study identifies who is gardening in the USA and provides useful information for public health efforts to increase gardening as a nutrition intervention. Findings suggest that home gardening may have beneficial public health outcomes. Future research should examine the benefits of home gardening using more rigorous study designs that allow for attribution of the outcomes to gardening (e.g. comparison group, longitudinal, process measures of garden productivity and measurement of behavioural pathways from gardening to improved diet or weight). Intervention research could examine a range of strategies to increase home gardening among different populations, such as peer gardeners, technical assistance from the Cooperative Extension’s Master Gardener Program or provision of reduced cost or free gardening supplies. Our finding of higher levels of gardening among families with children and a notable proportion of low-income households suggests that interventions to promote home gardening may be an effective strategy for reaching families with children and those at risk of food insecurity. Future intervention research could evaluate strategies to promote home gardens among populations at risk of lower dietary quality and obesity.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: The current research was supported with institutional funds from the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: M.C.K. directed the study and drafted most of the manuscript; R.P. analysed the data, prepared the tables and wrote part of the Methods section; A.H. helped design the study, coordinated data collection and wrote parts of the Methods section; D.W. drafted part of the Introduction; K.A. assisted with data analysis; R.H. helped design the study and advised on data analysis. All authors reviewed and edited the full manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Online written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020001329